The rematch between two UEFA Champions League semi-finalists took place on Tuesday night, as rivals and friends Thomas Tuchel and Julian Nagelsmann faced each other again in the match between PSG and RB Leipzig. The clash saw the PSG boss in desperate need of a win, having suffered defeats already at the hands of RB Leipzig and Manchester United, while Leipzig were looking for a win which would take them closer to qualifying for the next round.

It was Thomas Tuchel who came away the happier of the two managers, with his side picking up the three points in a 1-0 win, with the game taking on an unusual dynamic which many likely didn’t predict. In this tactical analysis, I will examine how Thomas Tuchel set up his side to nullify RB Leipzig, how Leipzig looked to combat this with their build-up, and how Thomas Tuchel’s excellent continuous adjustments allowed his side to stay in control of the game.

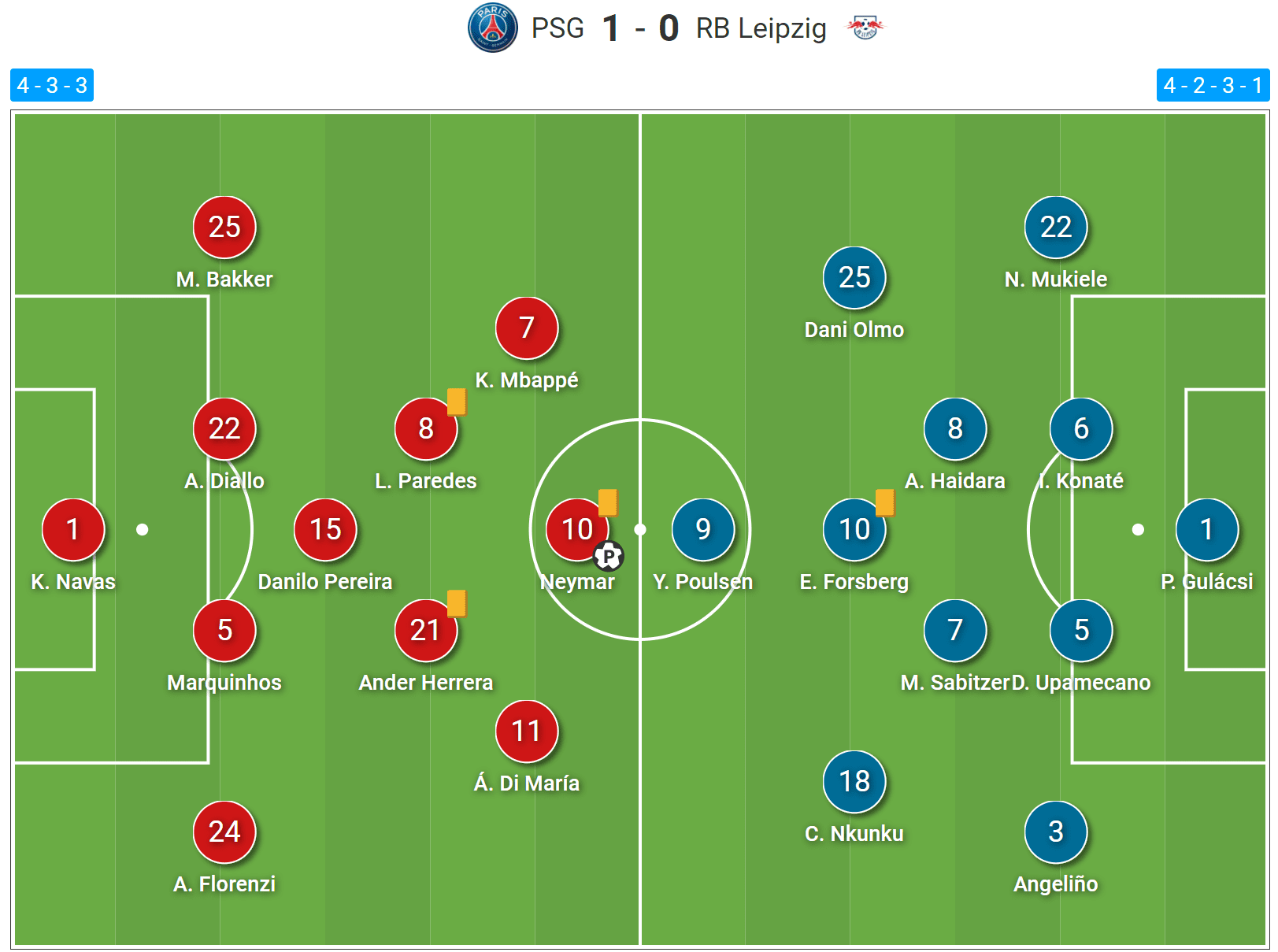

Line-ups

PSG lined up mainly as expected, with former Ajax man Mitchel Bakker starting at left-back, with the formidable front three of Kylian Mbappé, Neymar, and Ángel Di María starting up top. The positioning of these players changed throughout the game, and is something I will discuss. RB Leipzig meanwhile went with a fluid system, which fluctuated between a 4-2-3-1, 4-1-4-1, and switched to a back three often.

PSG defensive structure

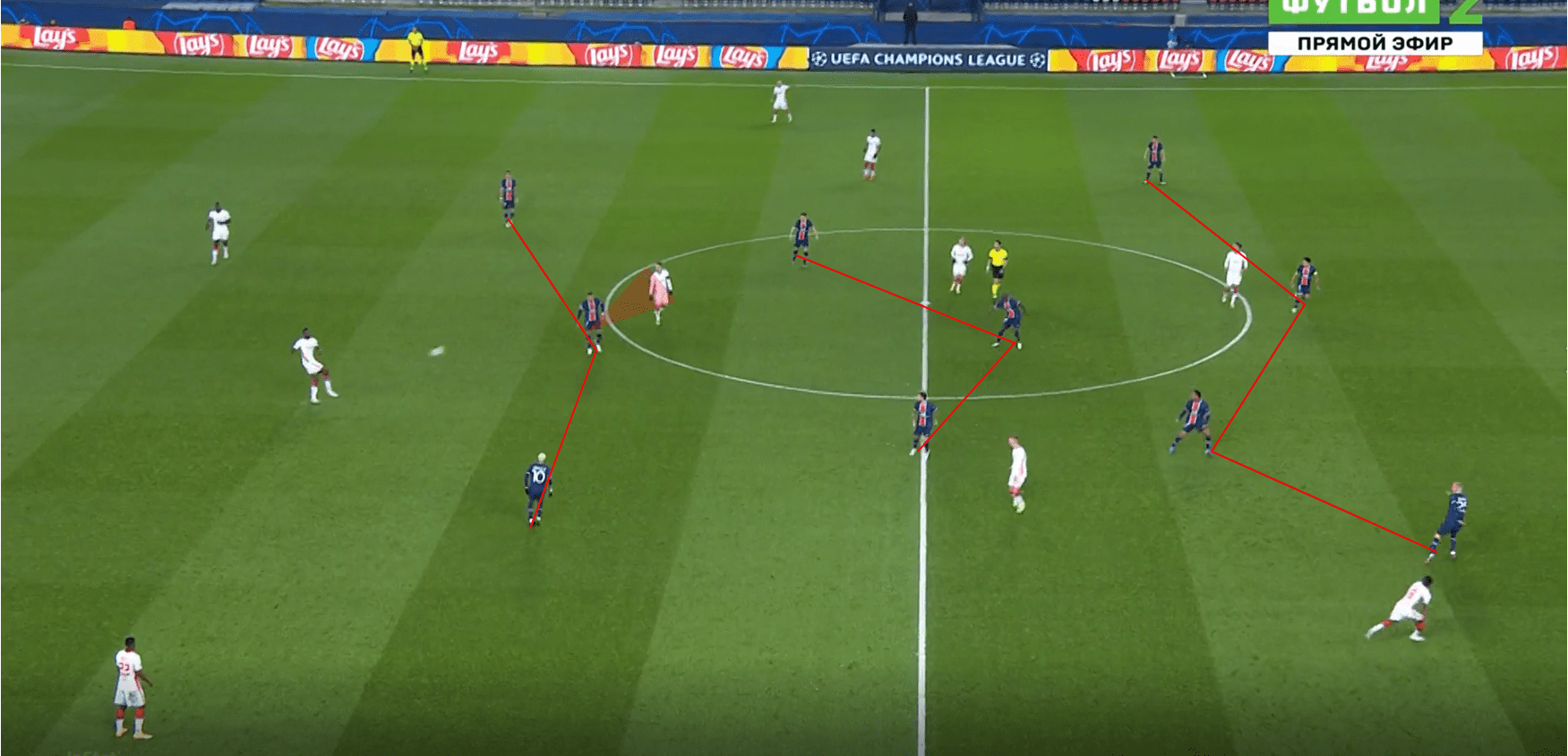

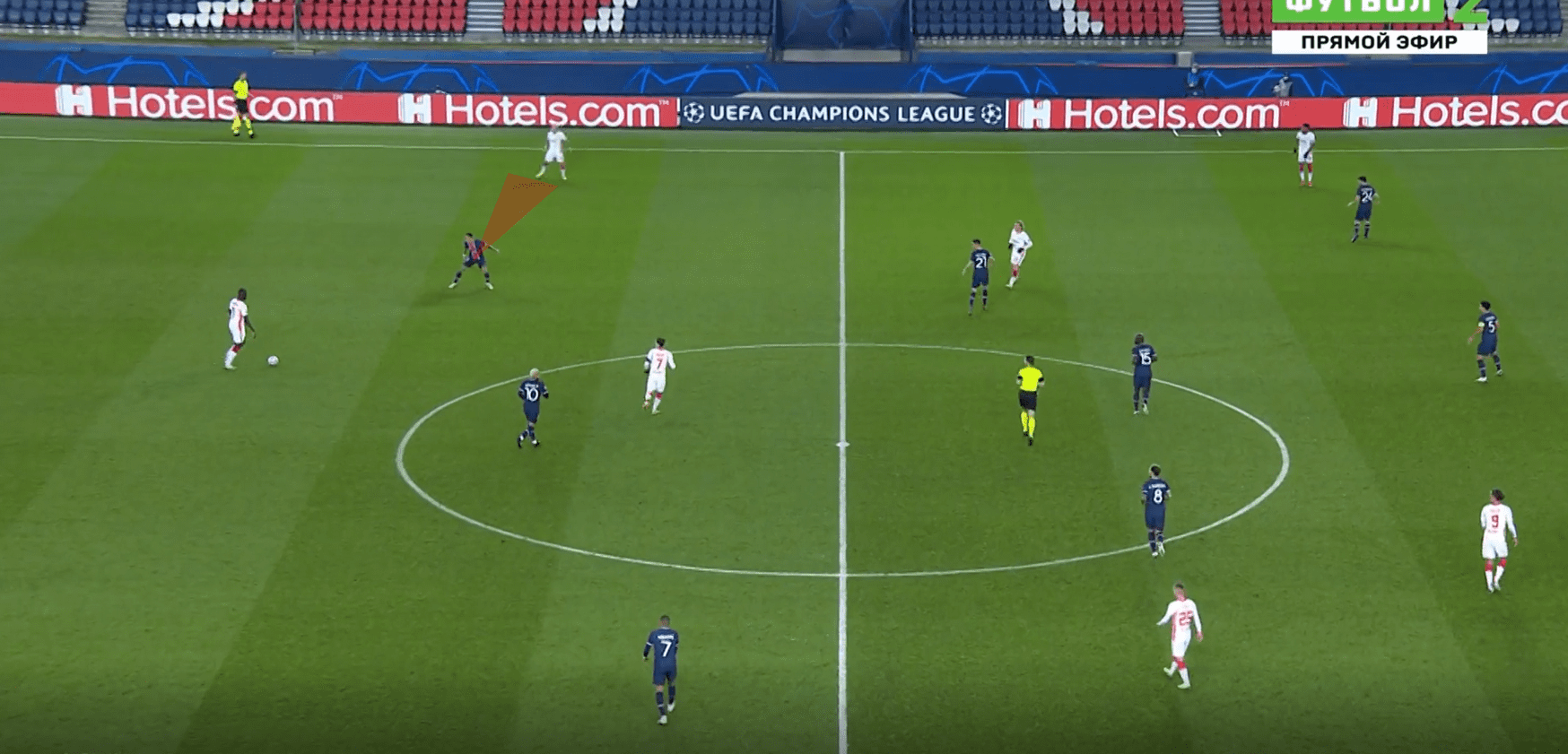

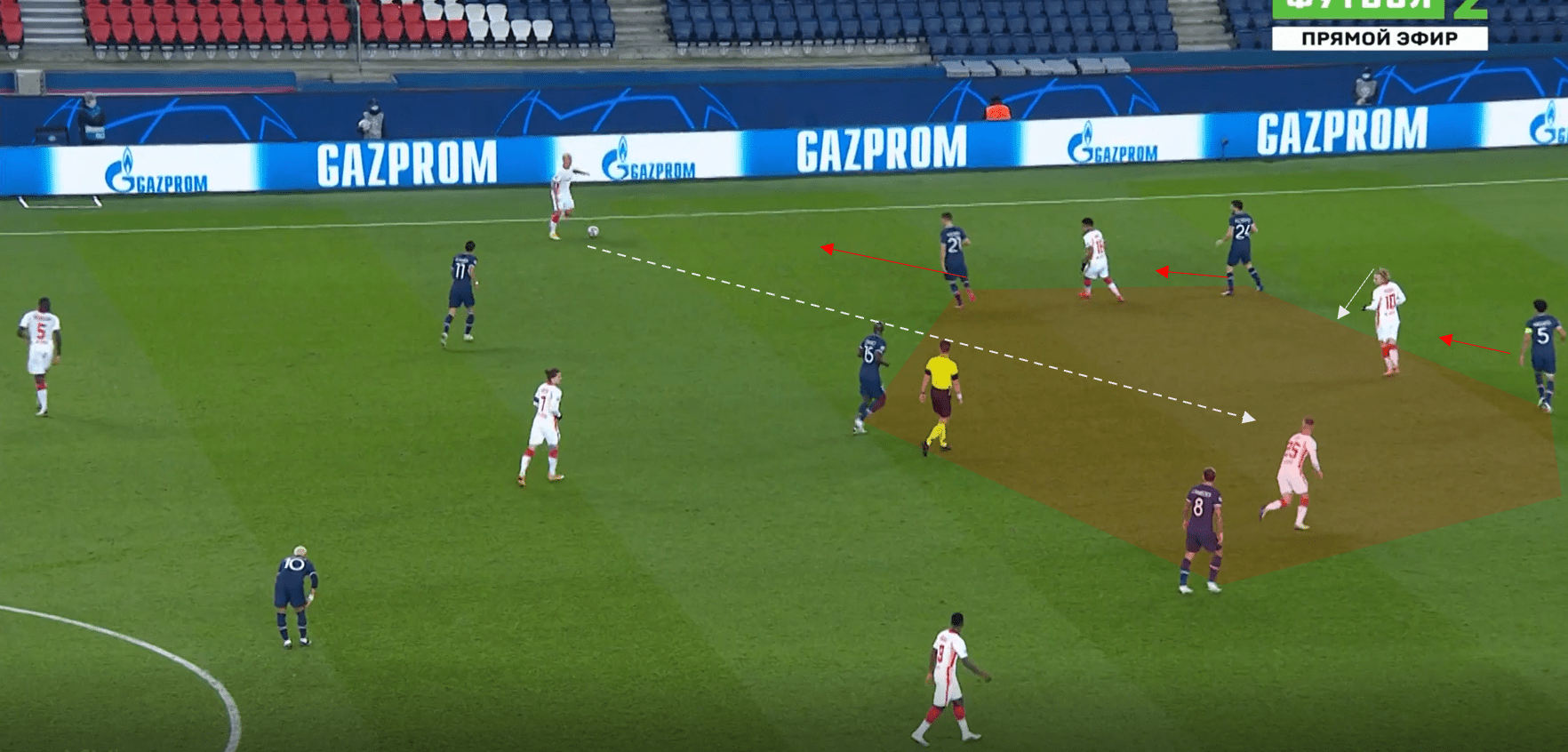

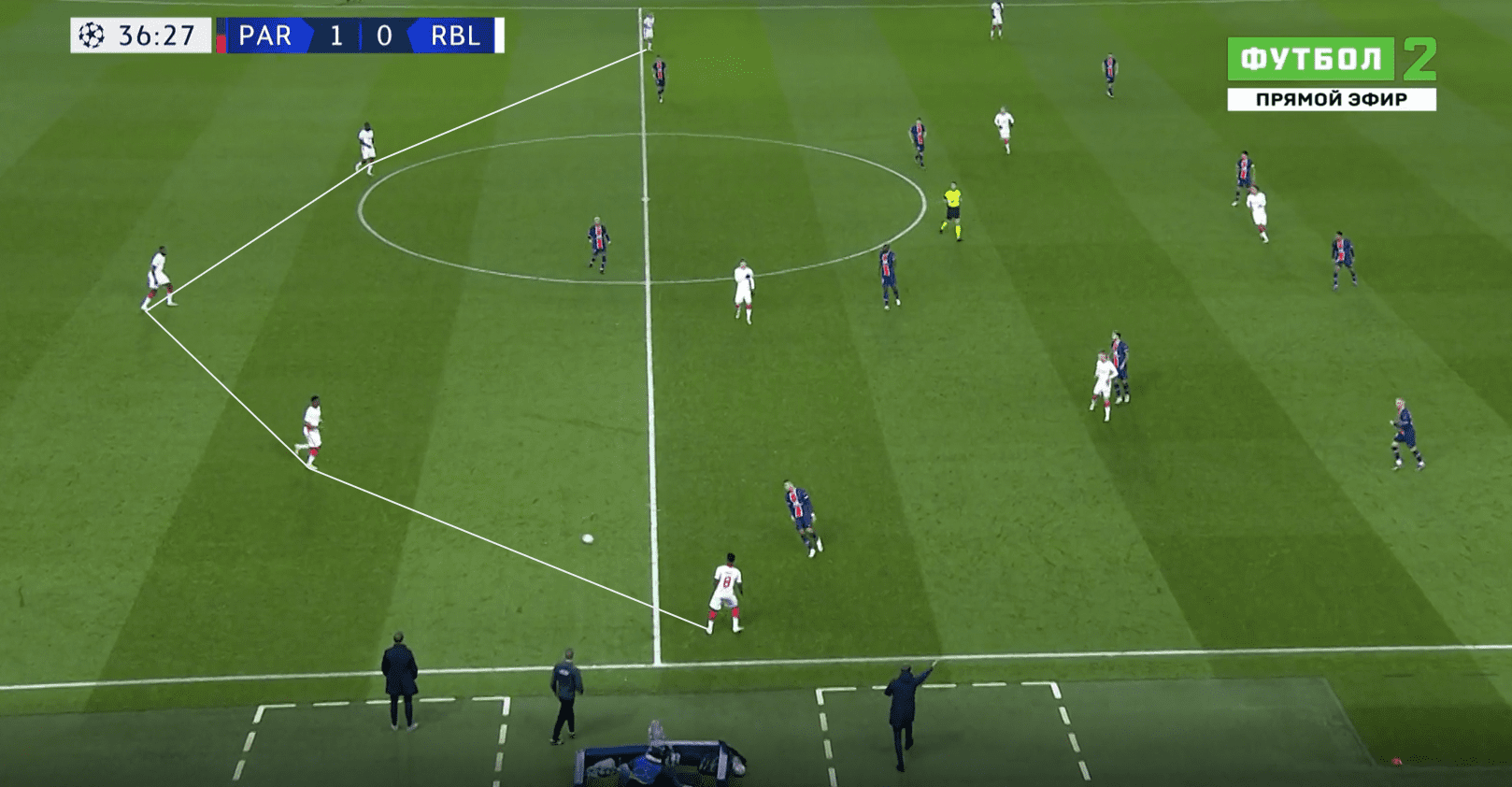

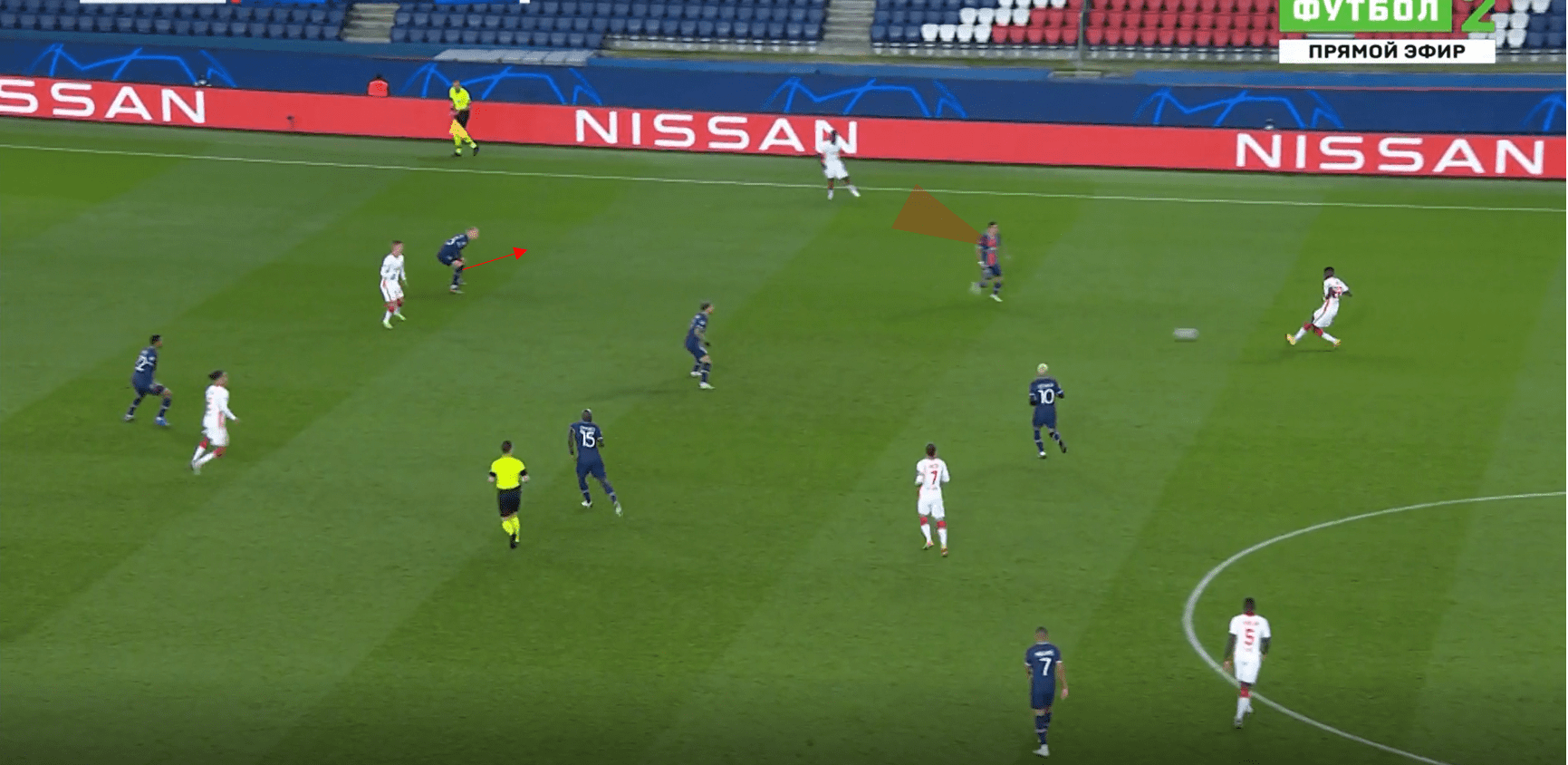

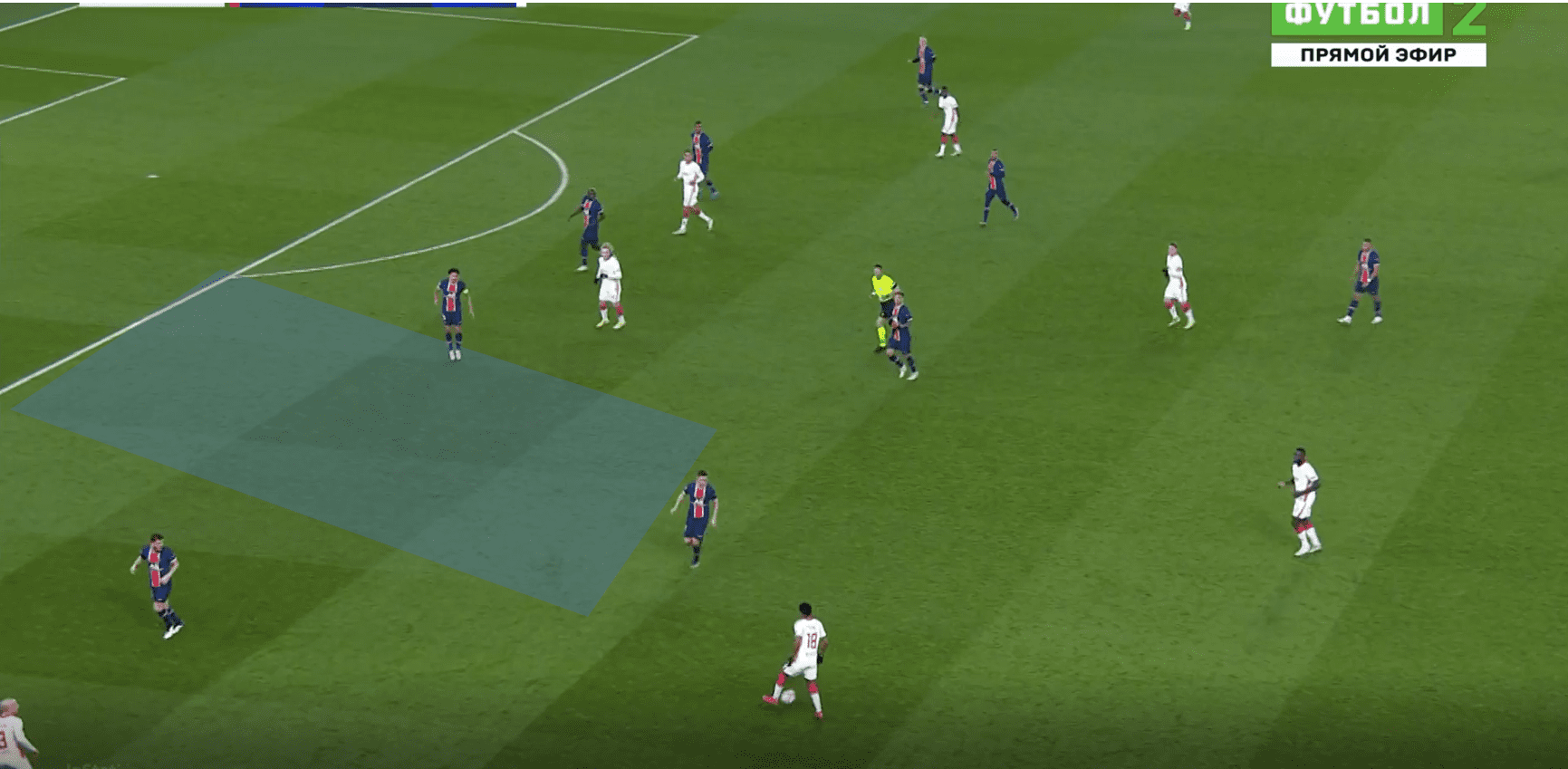

PSG pressed in a 4-3-3 structure, and were mainly passive in the game, with their PPDA increasing as the game went on. We can see an example of the shape they took up early on in the match, with this 4-3-3 clearly visible. The central striker, which fluctuated between Neymar and Mbappé, would often apply little pressure to the centre-backs, and would instead look to try and keep the RB Leipzig pivot (Marcel Sabitzer) in their cover shadow. This allowed for PSG to maintain a three-man midfield who could press nearby options, and so central overloads were incredibly difficult to produce for Leipzig in the early parts of the game.

We can see another example of this 4-3-3 below, with again the central striker trying to cut access to the pivot while the centre-back is left free. The left-winger here looks to mainly cut access to the Leipzig full-back, although he doesn’t do this well, and so the lane to the wide area is left open. PSG have numbers in midfield so that Leipzig can be covered well in these areas, and so Upamecano plays a pass out wide, which progresses the ball for Leipzig but isn’t too difficult to deal with for PSG.

We can see Leipzig are still operating with Sabitzer as a single pivot, rather than using a 4-2-3-1 as the Wyscout graphic suggested.

We can see another example below where Di Maria looks to cut the lane to the wide player. Leipzig form a back three and no pressure is applied to the central centre-back, with Neymar covering Sabitzer again. Ander Herrera moves higher with Christopher Nkunku in the half-space, while Di Maria arcs his run in order to press the left centre-back from outside to in.

In a similar example here, the Argentinian does the same and cuts the lane while Herrera marks the central option and Neymar covers the pivot. This kind of press is one we see most often from Liverpool, with the focus of pressing from outside to in looking to force the opposition centrally.

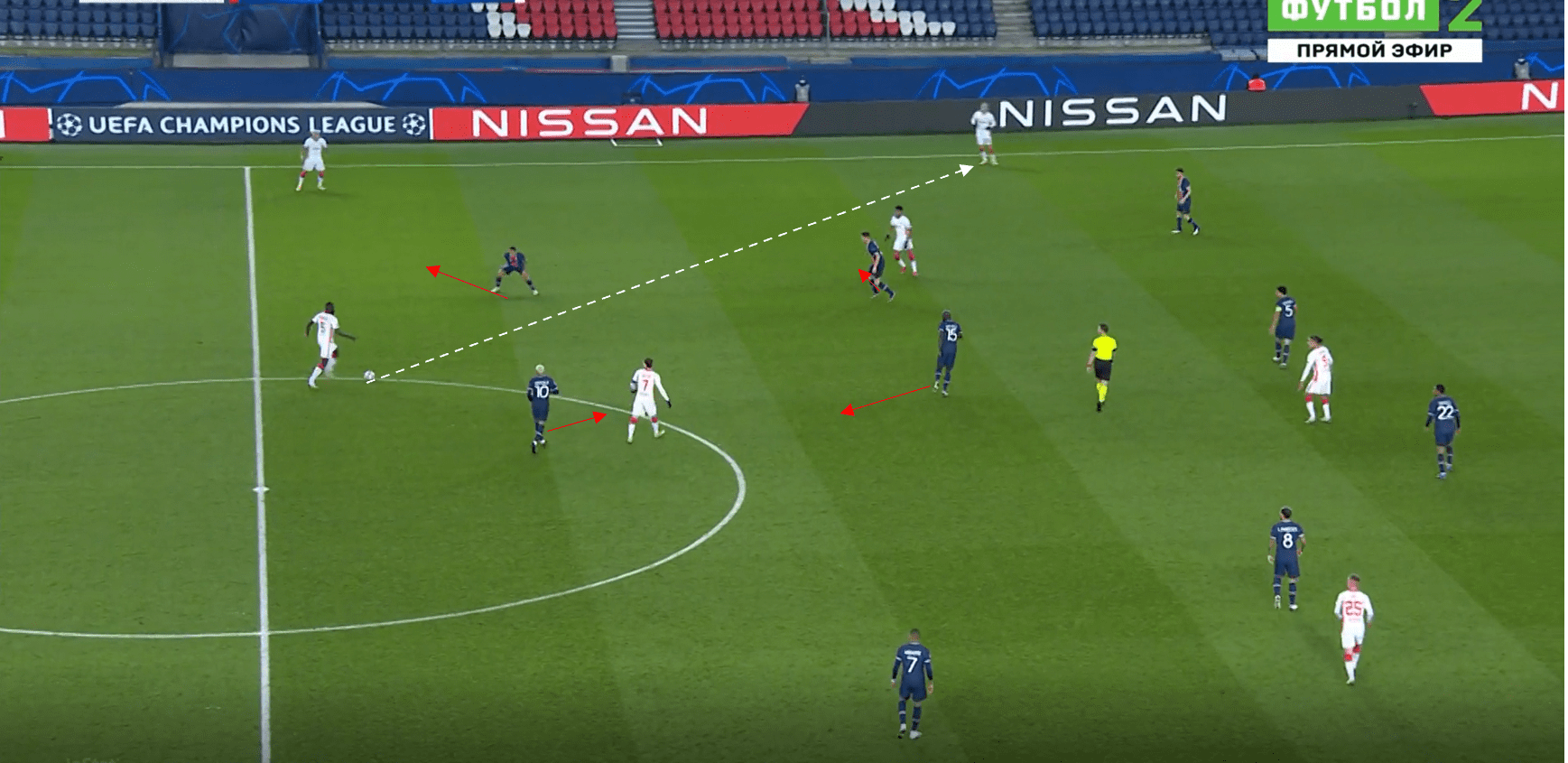

The interesting thing about this press though, was that Mbappé largely didn’t perform his role well, and he often wouldn’t cut the lane to the full-back well at all, meaning PSG’s press became disjointed and could be broken. We can see an example below where Mbappé makes a poor attempt to cut the lane to the full-back.

Neymar also doesn’t cover the pivot well here, and after probably 30 minutes he really struggled to do this and didn’t really attempt to that often, resulting in PSG’s midfield having to step forward more to deal with the threat.

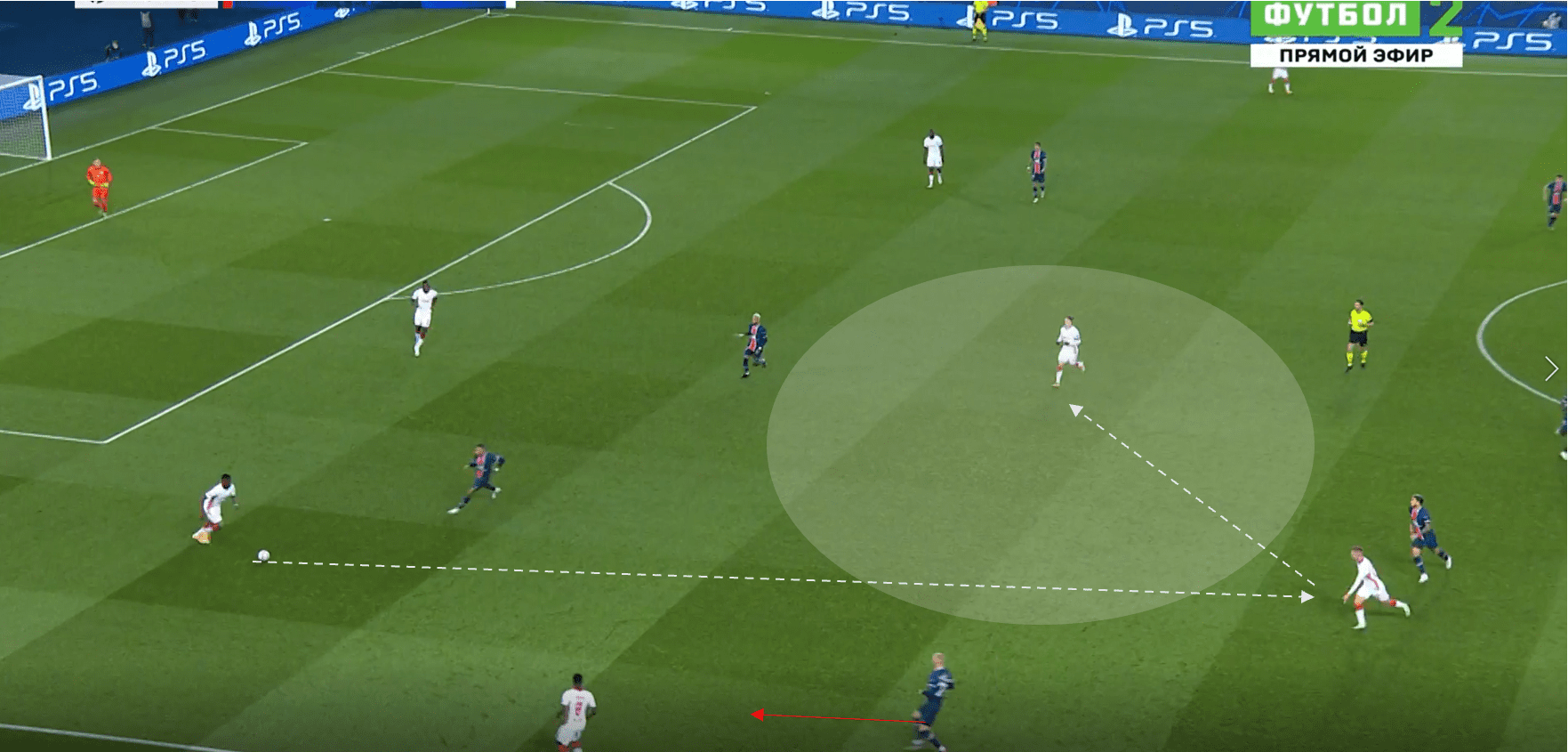

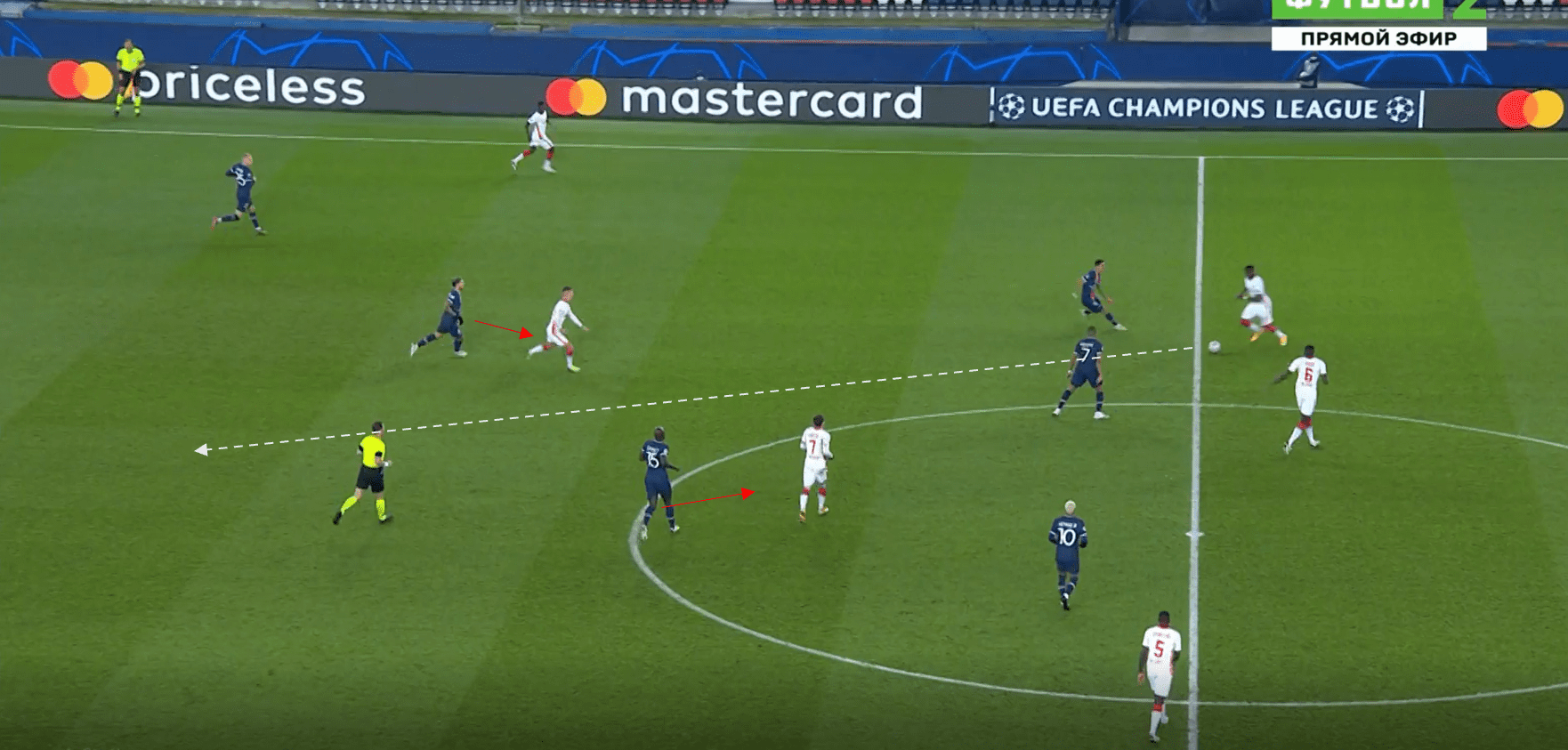

We can see here that a combination of poor pressing from Neymar and Mbappé allows Leipzig to progress the ball and break PSG’s press. We see Mbappé doesn’t prioritise cutting the lane to the wide player, which is perhaps due to Neymar lazily wandering back rather than covering the pivot. As a result, Nordi Mukiele can receive the ball and is allowed to turn, and the Frenchman also has the option of playing to the pivot centrally.

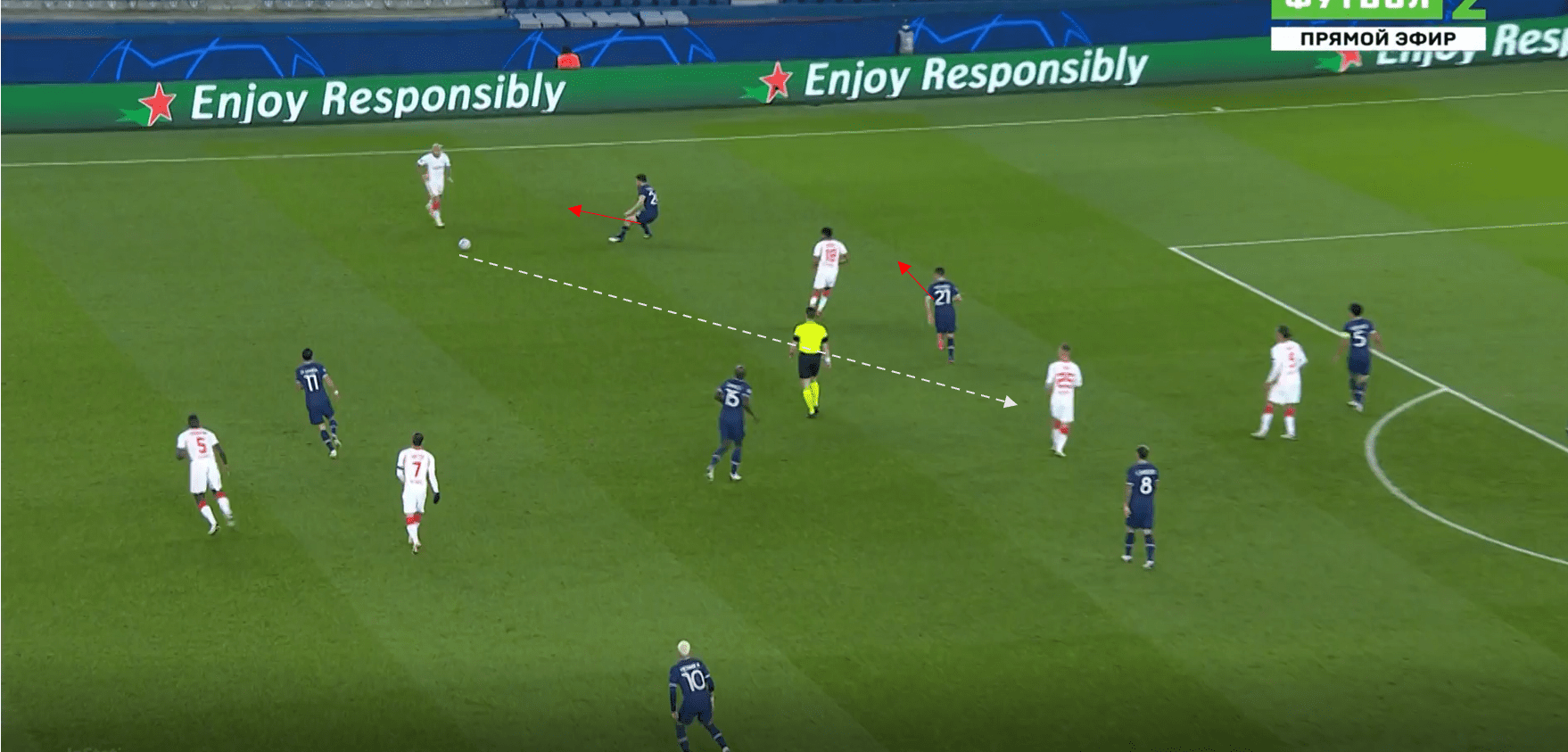

We can see the knock-on effects this poor pressing has below. Because Mukiele can receive and progress the ball, nearby passing options have to be covered. Therefore, with RB Leipzig in a 4-1-4-1, the nearby winger had to be pressed to prevent them from receiving. This led to the full-back moving outwards and wide often in order to press the Leipzig winger. As a result, the half-space would open, which allowed for one of the more offensive-minded midfielders to run into space to support, which Dani Olmo does here. As I’ll discuss in the next section, this was a recurring problem for PSG.

PSG’s wide problem and Leipzig’s build-up

For PSG’s early press, if the Leipzig full-back had managed to receive the ball, and was being pressed by anyone other than the front three, they weren’t in an ideal shape. Di Maria generally did a better job at preventing the ball from getting to the full-back, but even he struggled at times.

We can see here for example Di Maria allows the ball to reach the Leipzig full-back, and so PSG’s nearest central midfielder opts to press wide. The RB Leipzig winger moves wide to occupy the full-back, while one central midfielder also moves high in the half-space. Herrera presses at a poor angle, and so his pressing run means central protection is hindered slightly, meaning Leipzig’s other central midfielder Dani Olmo can drop into the half-space to overload it. We can see Emil Forsberg even has a little scan to check that Olmo is there, clearly showing Forsberg’s intention is to pin the defender for Olmo to receive the ball.

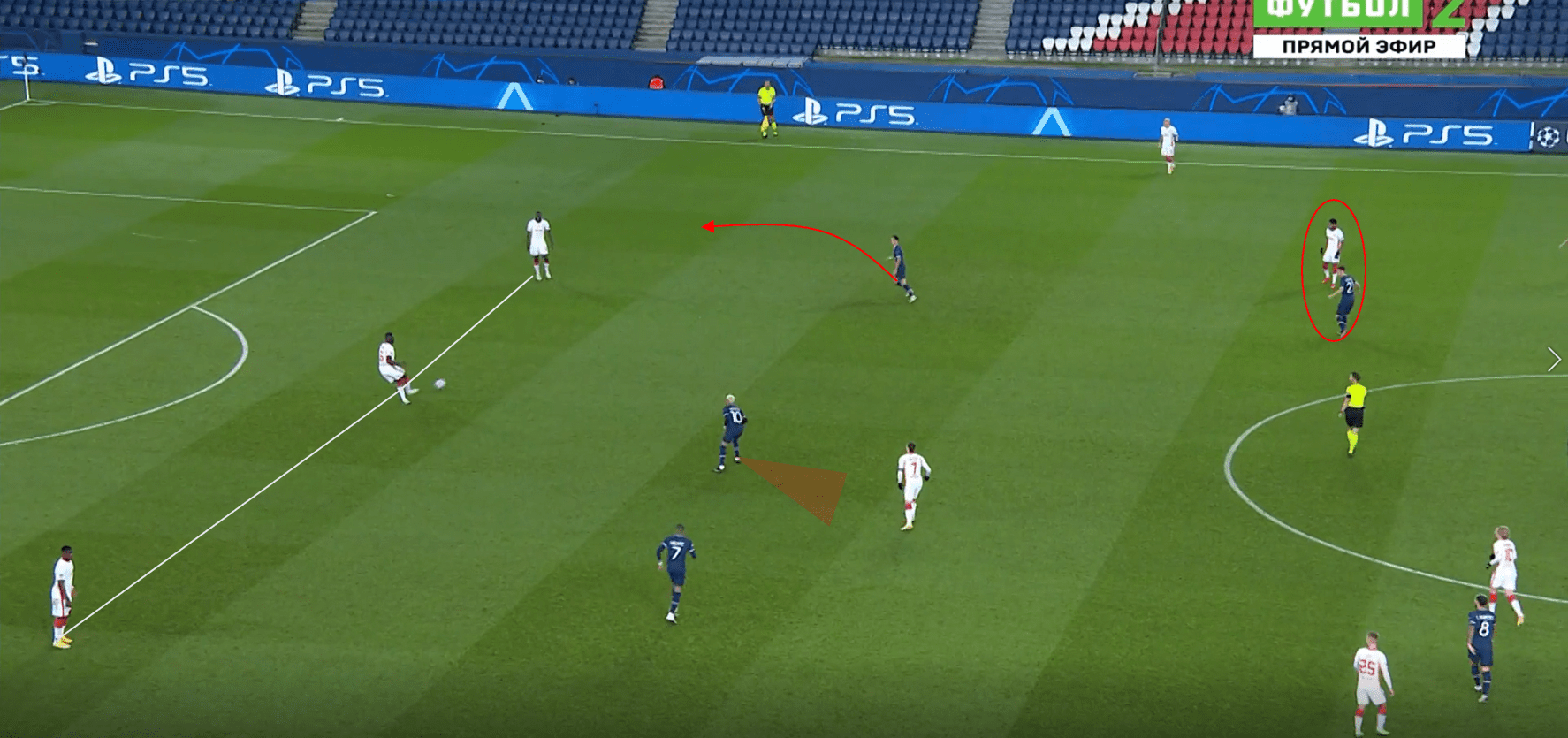

Having a lack of pressure on the ball didn’t help PSG either in preventing this wide problem, as Leipzig’s centre-backs did an excellent job of dribbling to try and create passing lanes. We can see an example here where Di Maria cuts the lane to the wing-back well initially, but Upamecano makes a diagonal dribble to open the lane to access Angeliño.

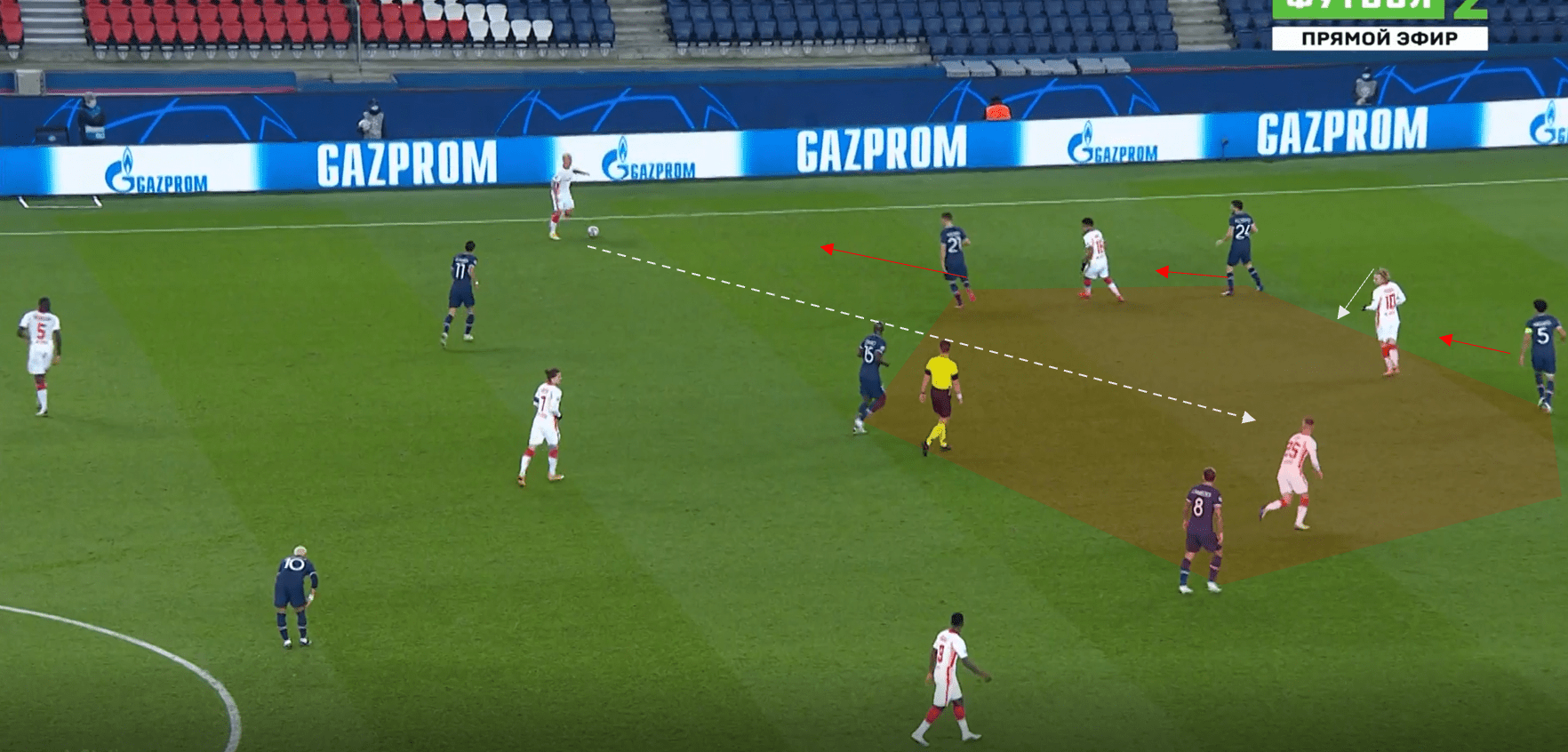

As a result of this pass into the full-back, the PSG full-back has to move across to apply pressure. Because enough width is provided by the full-back and the full-back is engaged, the winger can tuck inside into the half-space, and as a result, is occupied by a central midfielder. Again, with this central midfielder moving wider, a central lane opens up, and once again Dani Olmo acts as this spare player.

This idea of creating a plus one using a central midfielder was one that Leipzig looked to use often, but they rarely created chances from it, with their quality in this area often letting them down. We can see an example here where Nkunku has the ball and provides width, causing Angeliño to look to occupy the centre-back inside the half-space. The duty then falls to Emil Forsberg to act as the overloading player, and Danilo does a good job of tracking him. Dani Olmo would also be an option given a different situation.

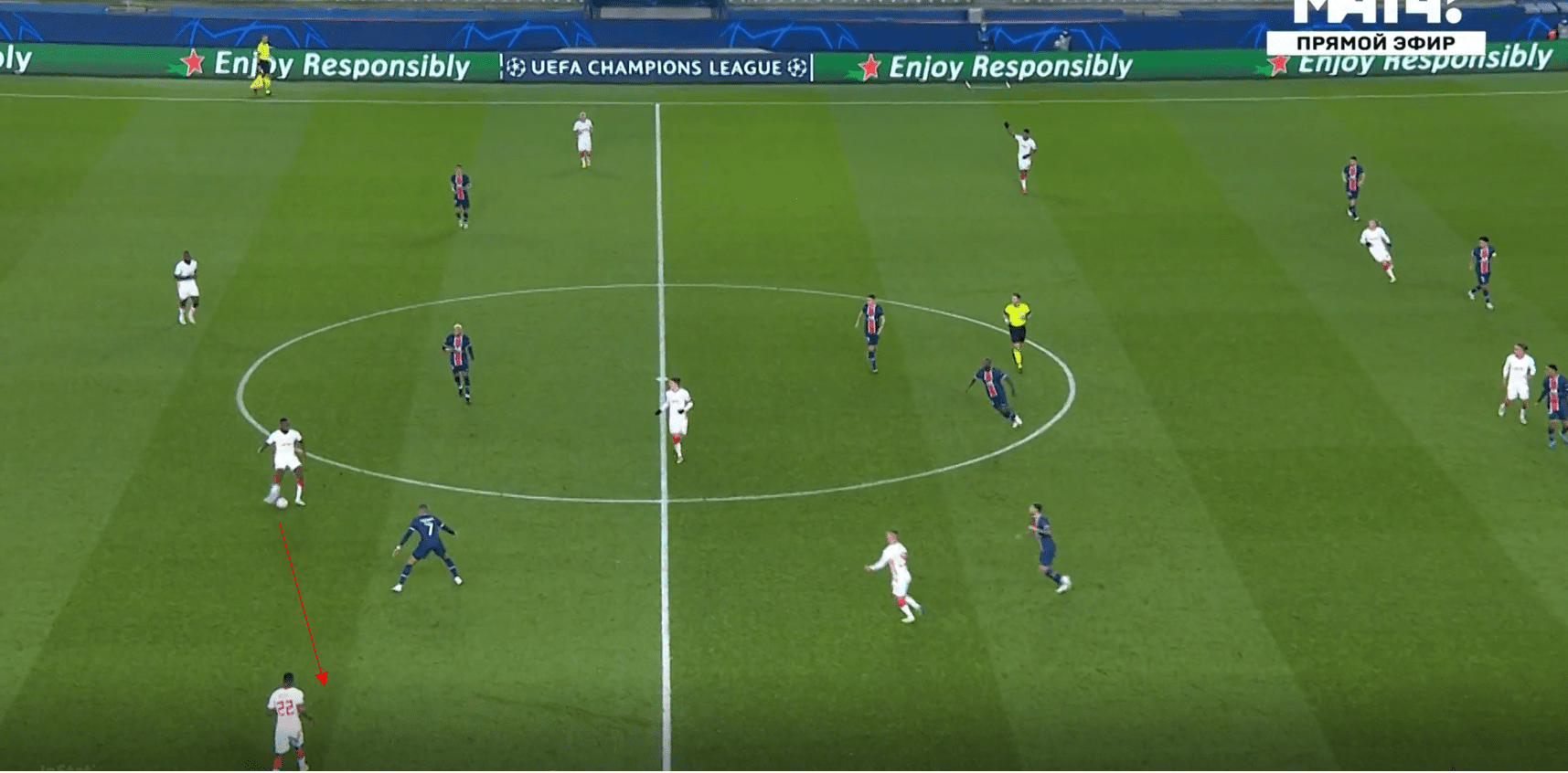

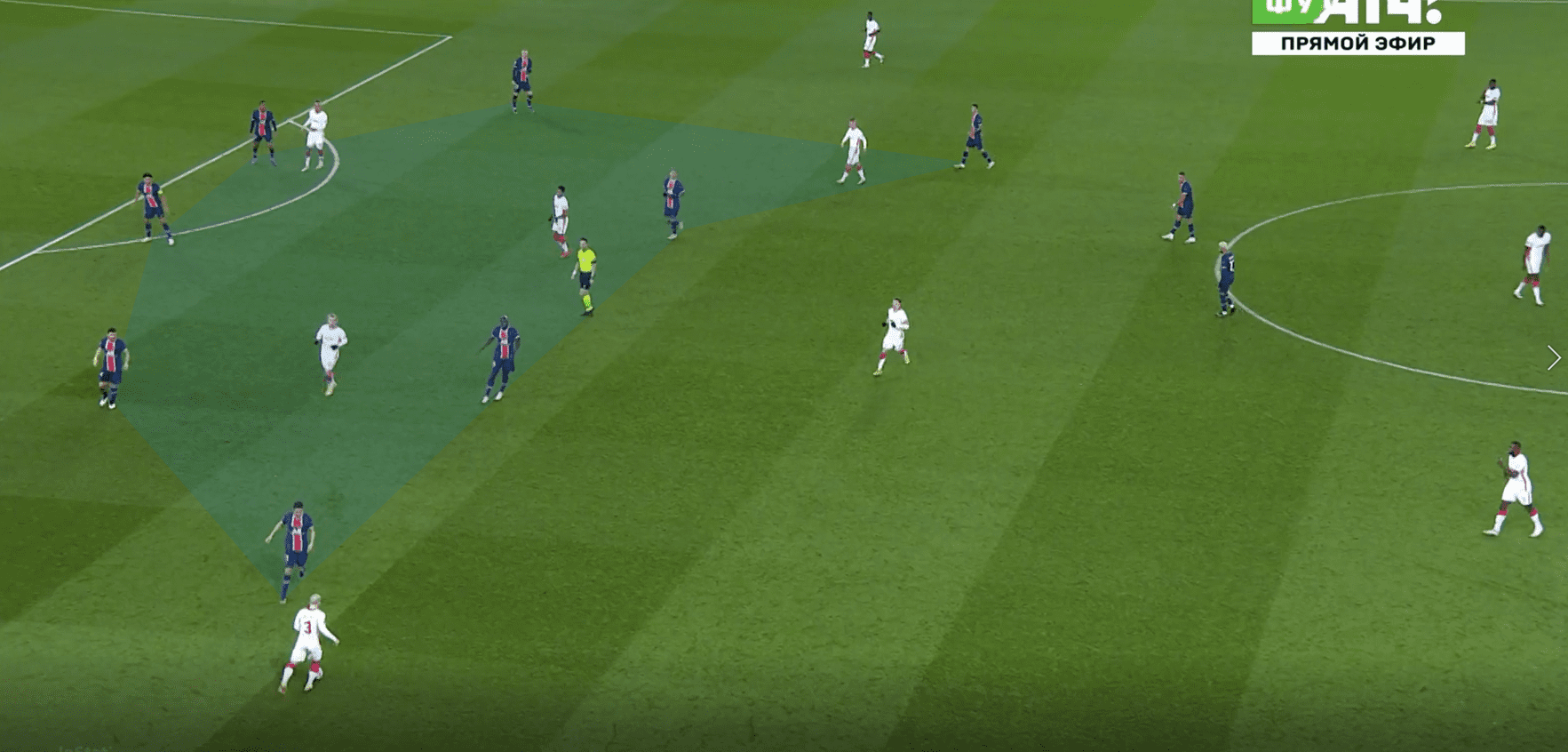

As I’ve briefly mentioned, Leipzig adopted a fairly fluid shape, and so Haidara would often drop onto the right side to act as a wing-back, with Mukiele tucking in as a wide centre-back to form a back three. We can see an example of this shape below, with Leipzig still maintaining a single pivot in Sabitzer.

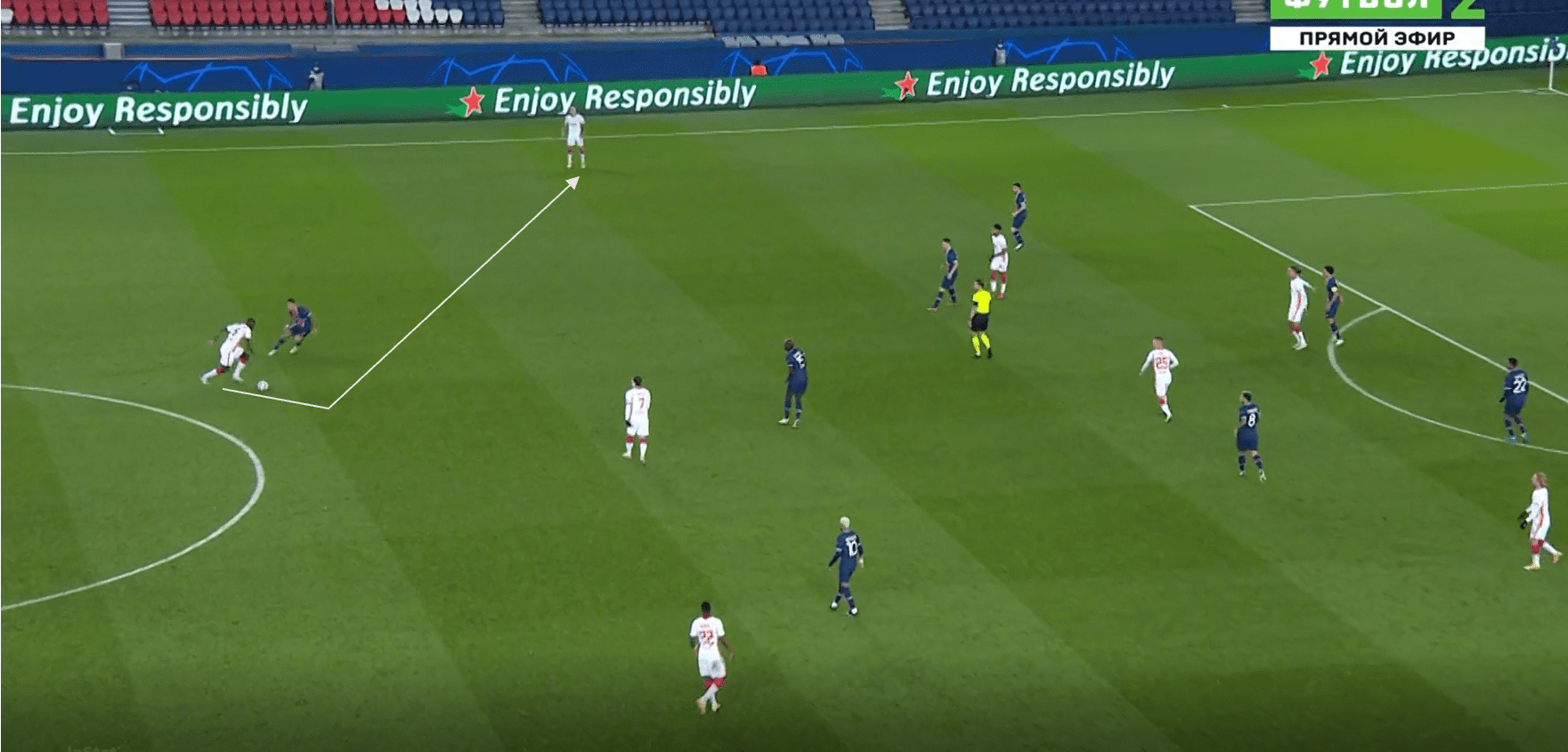

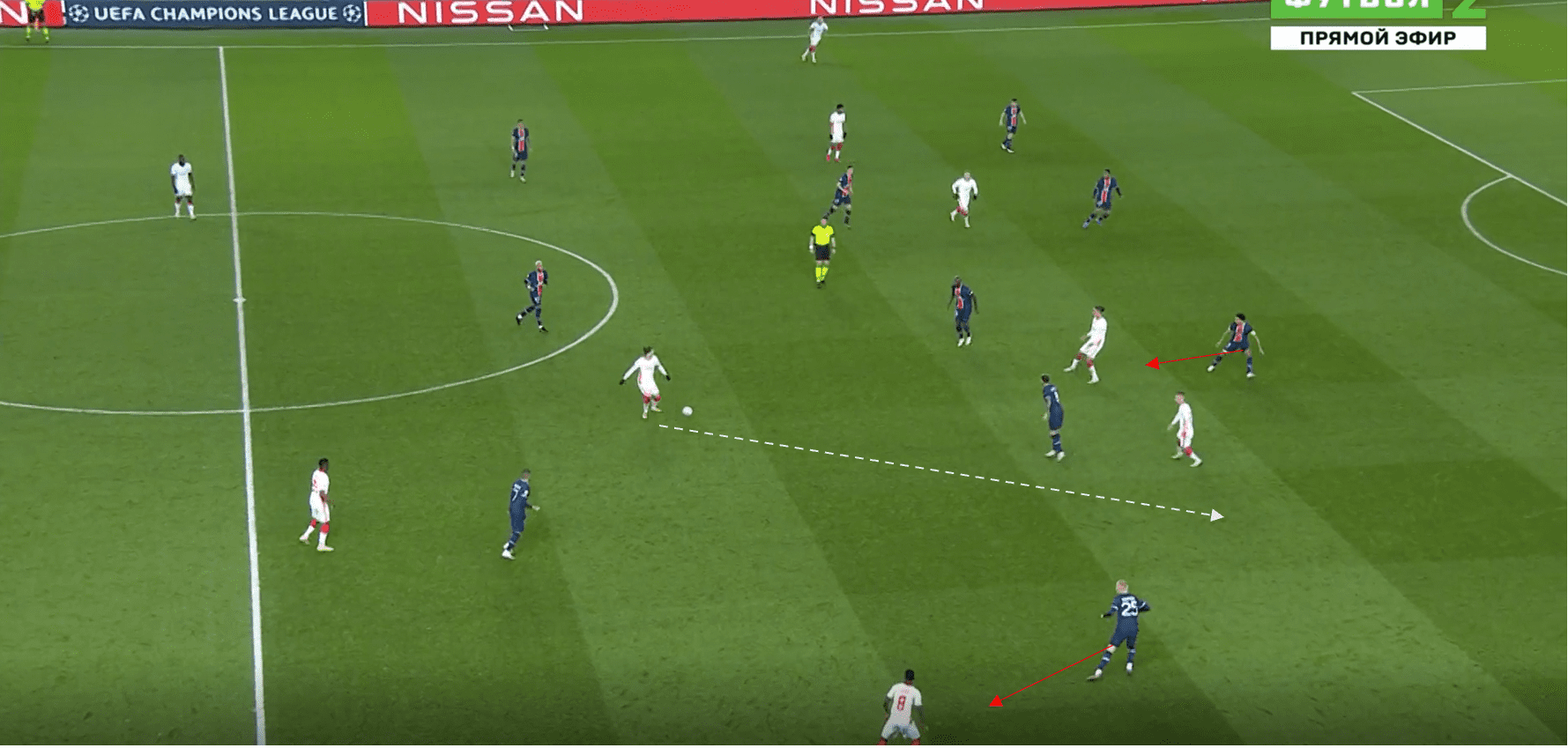

The use of a back three famously helps to stretch the first line of the press, and so Leipzig used this with the intention of influencing the positioning of the winger in order to access the wide areas. We can see an example of the back three being advantageous for Leipzig here in a deeper area. Mbappé now presses the wide centre-back, meaning the wing-back is free, and so the full-back pushes higher and wider to press. This opens the lane for Olmo to drop and receive, and Leipzig can now access the pivot as a result of this access to the half-space. The pivot is unmarked, and so Leipzig have escaped the pressure.

We can see a final example of this here in a deeper area, where Neymar doesn’t do his job and allows the ball to be progressed into the pivot, who can pass forward. Leipzig are in a back three with Haidara out wide, and so PSG left-back Mitchel Bakker has decided to press him initially. Yussuf Poulsen virtually always maintains central positioning and occupies the centre-back, and so all Leipzig need is a midfielder to drop into space to overload this player, which Dani Olmo again does, albeit with some dubious marking by PSG’s midfielders in front of him.

Tuchel adjusts, Leipzig struggle

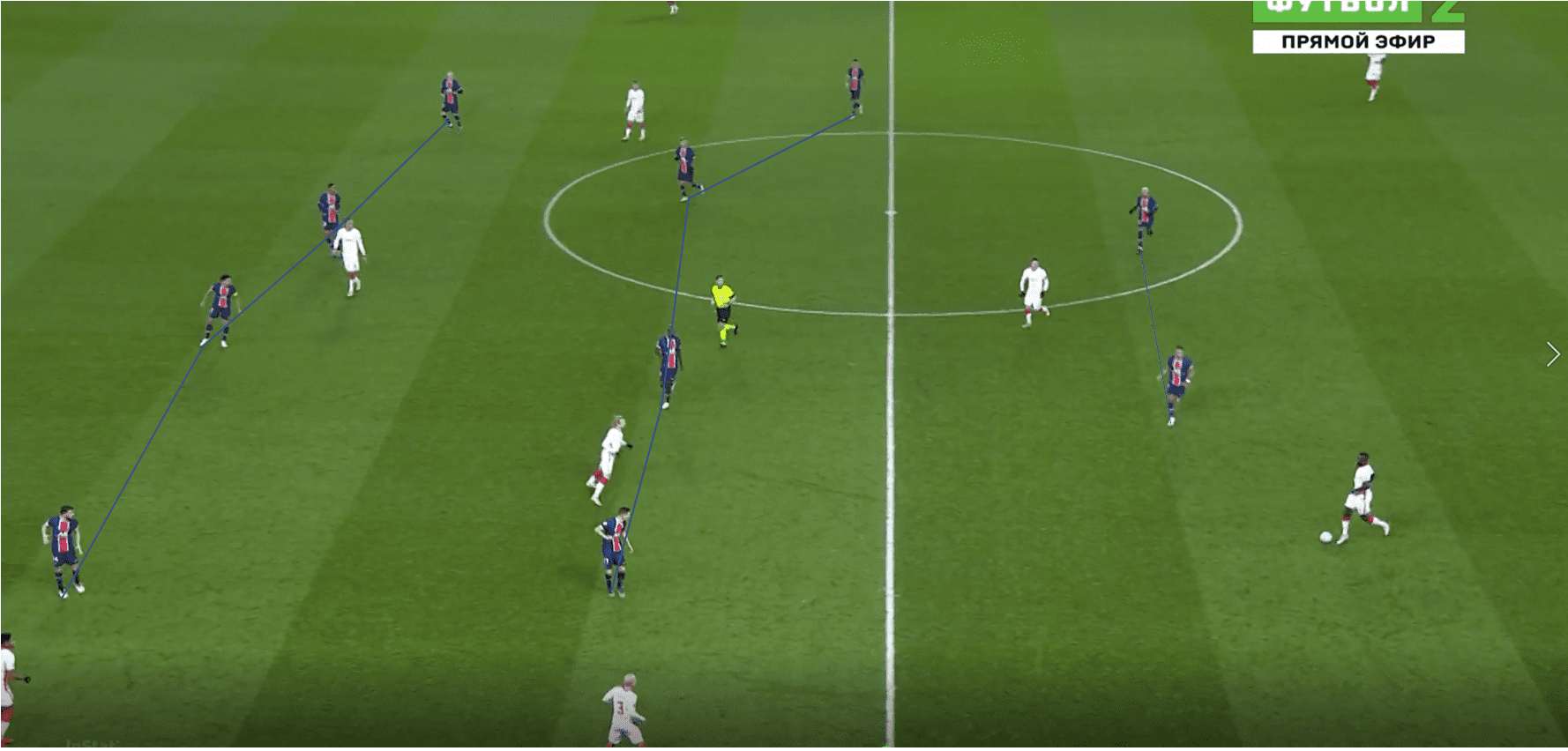

Most of this analysis has focused only on situations and trends within the first half, and at half-time Tuchel seemed to adjust his pressing scheme slightly, before adjusting it again midway through the second half. In an attempt to solve this wing problem, Tuchel switched PSG into a 4-4-2, with their two worst pressers in Mbappé and Neymar given little responsibility up front.

The reason for this switch was that it allowed permanent occupation of the wide area or full-back by a midfielder, meaning the PSG full-back could, in theory, sit deeper and prevent Leipzig from progressing the ball. We can see this 4-4-2 PSG shape below, with the full-back now pressed by a winger while the half-space is covered by the central midfielder. The strikers would still try to cut access to the pivot, but this quickly faded away as the second half went on.

Now, in theory, the full-back could prevent ball progression, as we mentioned before. The full-back still had to maintain discipline and on this particular occasion here, Bakker shows that early in the second half, he wasn’t entirely certain of his responsibilities. Di Maria does a great job of cutting the lane to the wing-back, but Bakker also gambles on the wing-back receiving and goes to press, despite the passing lane into the half-space being clearly open and the body shape of the centre-back showing he is playing inside. This isn’t an issue which happened often, but I feel it shows the responsibilities of the players well.

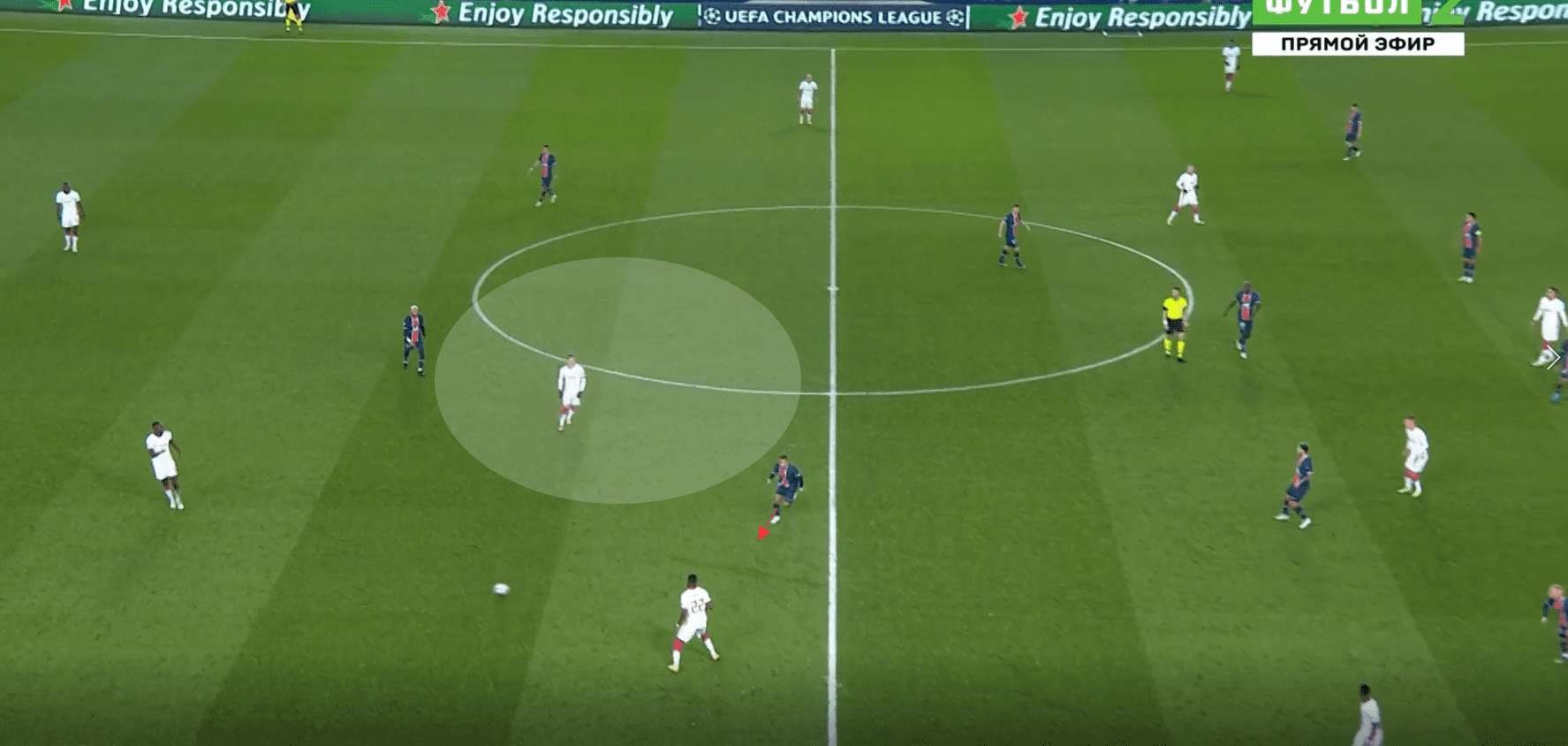

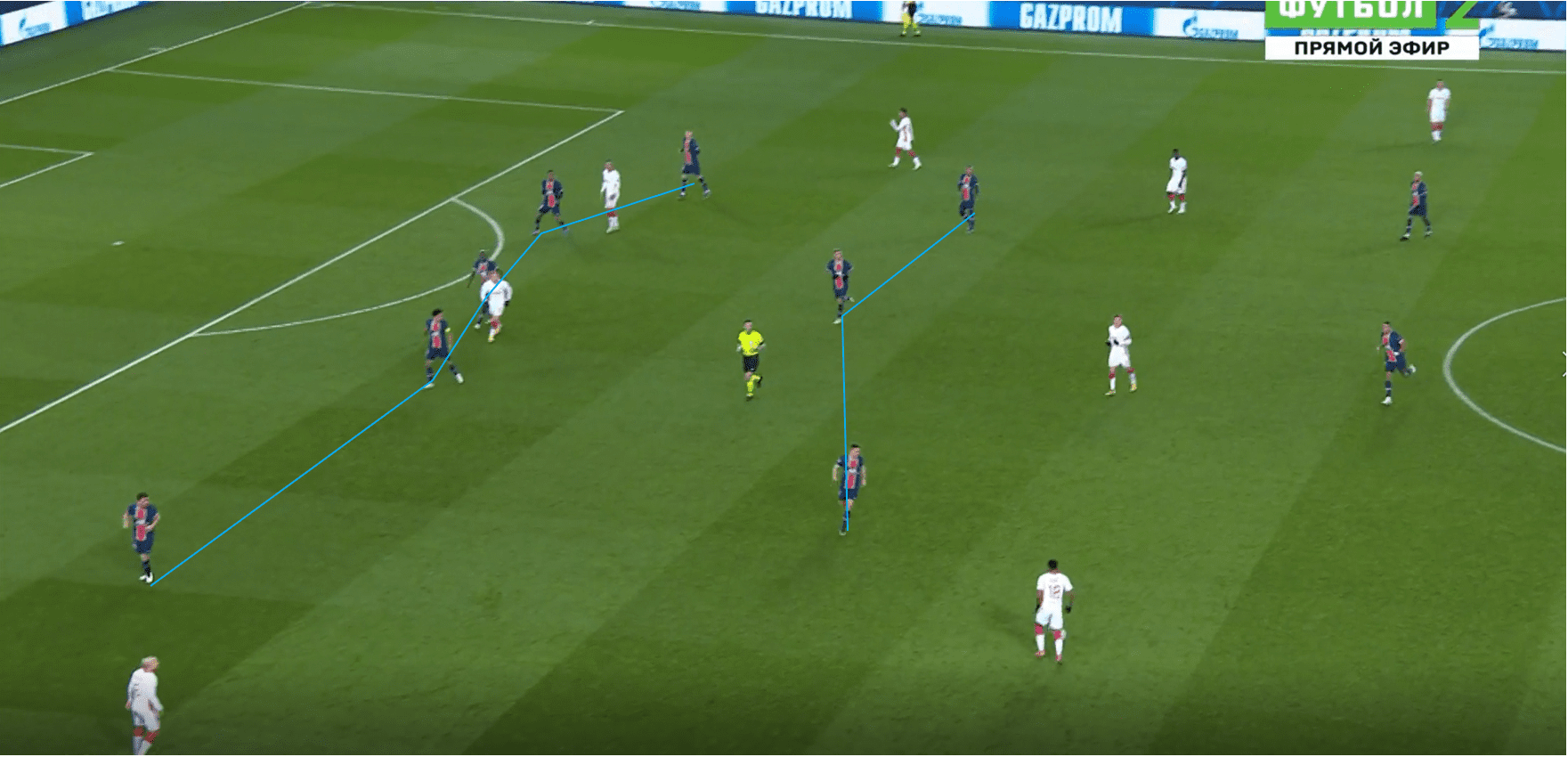

We can see the 4-4-2 being used again here, with the compact structure stifling Leipzig for large periods of the game. We can see both central midfielders have a player to mark, while Marcel Sabitzer acts as a free player in central midfield, with an obvious 3 v 2 overload in the middle created. PSG were aware of this, as were Leipzig, but they couldn’t take advantage of this, other than using half-space combinations which I have shown earlier.

We can see an example of PSG’s shape jumping back to more like its original structure here, with Di Maria seeing an opportunity to win the ball higher. The two central midfielders both mark nearby options, who are split, and so a pass is available through the middle of them. However, with two central midfielders committed to create this passing lane, and with Leipzig in a back three, only two/three players are available to receive the ball, and so Leipzig can’t do much with it.

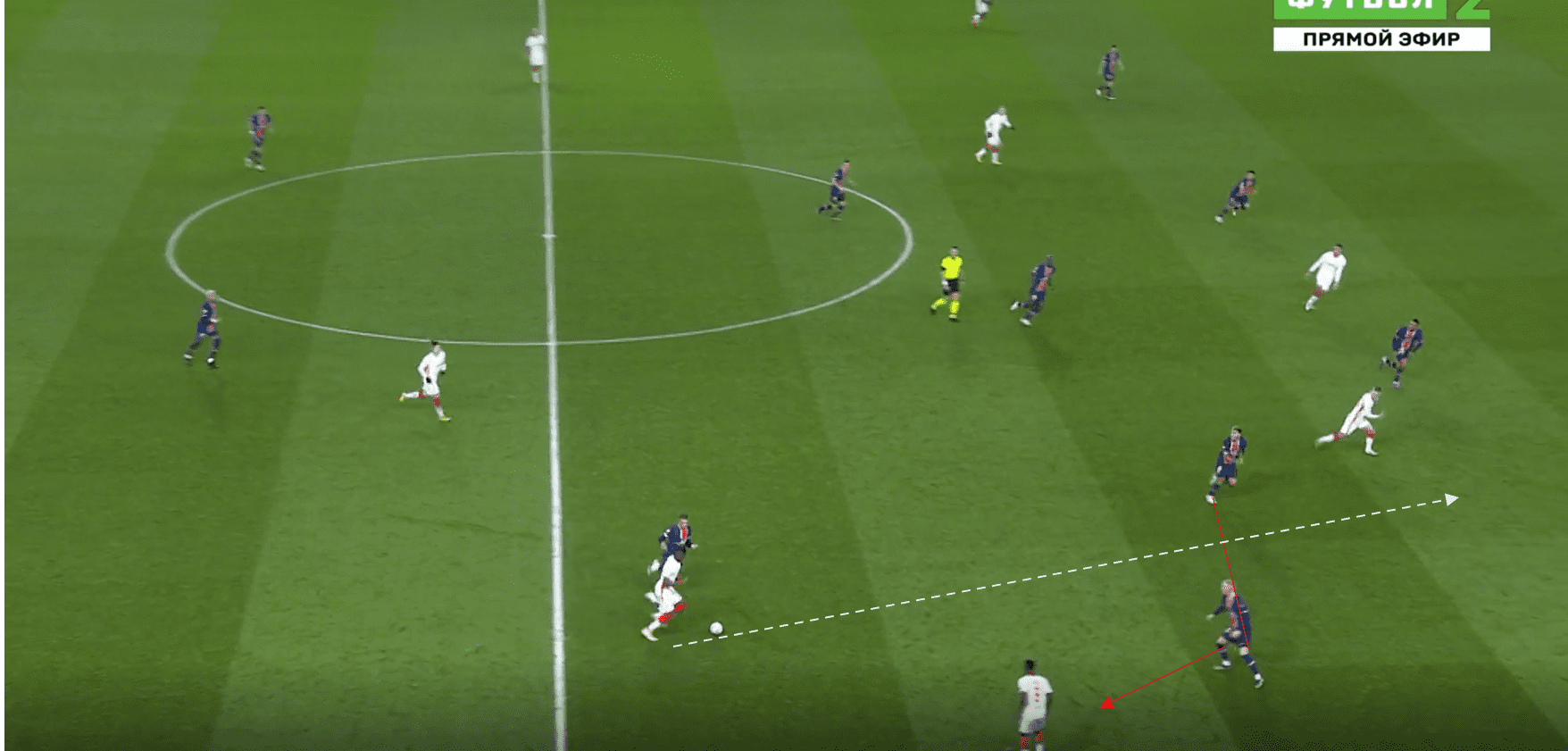

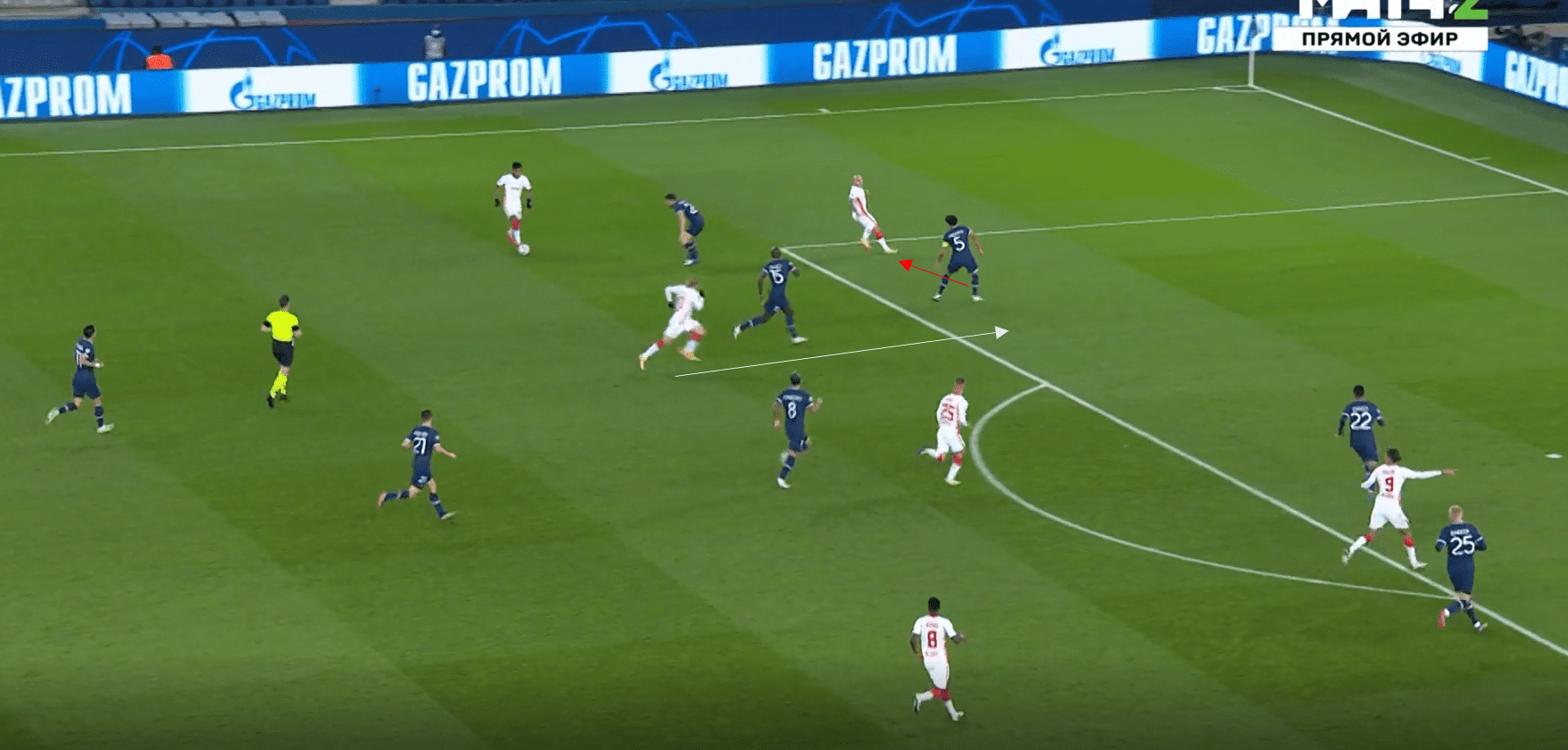

In a further adjustment, at around the 65th-minute mark, PSG switched to a 5-3-2, with Danilo Periera dropping into the backline as a centre-back. This adjustment was likely made to commit more players behind the ball, and to allow for the half-space to now be marked from behind rather than from in front with a central midfielder using their cover shadow. We can see this 5-3-2 in action below, with the strikers again not contributing much defensively.

The 5-3-2 didn’t change the problem too much for Leipzig, as they were still looking to engage a midfielder in a wide area in order to create an overload centrally, but the change in system did solidify PSG’s defence even more. Leipzig had little answer to this switch and looked devoid of ideas and we can see here that, for example, no occupation of the half-space or overload is seen anywhere.

Leipzig’s personnel didn’t particularly help either, with Alexander Sørloth brought on at around this time to accompany Yussuf Poulsen up front. This gave them more presence aerially and created low quality chances, but against a back five one of the key factors is pace and penetration in behind, and Poulsen and Sørloth simply didn’t offer that. As a result, Leipzig ended the game recording just over 1.0 xG in the game, with 64% possession recorded.

Conclusion

I haven’t really mentioned PSG’s attack in this analysis, and that is simply down to the lack of it in the game, with PSG behaving passively throughout the game and settling for less of the ball. They generated an 0.52 non-penalty xG according to Wyscout, and did well to capitalise on an RB Leipzig build-up mistake early in the first half to win the penalty.

I wouldn’t say either team performed excellently. RB Leipzig struggled to create many chances but in the deeper phases of build-up, they exploited PSG at times – particularly in the first half. PSG capitalised and defended well, but their first-half tactics were ultimately flawed, and perhaps a better team would have exploited this. Thomas Tuchel won PSG the game with his tactical adjustments throughout, and had he not adapted to the wide pressing problem, Leipzig may well have exploited it further for a goal.

Comments