You can say a lot about Manchester City since Sheikh Mansour’s 2008 takeover but one thing you certainly can’t say is that he and his club haven’t been ambitious.

The scale of that ambition has been evident right from the beginning. After taking over a club that finished the 2007/08 season in ninth place, securing UEFA Cup qualification thanks to their domestic fair play ranking — a feat that then-manager Sven-Göran Eriksson described as: “a dream come true”, the new City regime made waves across the footballing landscape by signing Robinho for a reported £32.5m, setting a British transfer record in the process.

The entire atmosphere around the club immediately changed. No longer was UEFA Cup qualification thanks to their fair play record considered the pinnacle. Robinho’s compatriot, Jo — who was also signed in the summer of 2008 — declared just months after Eriksson’s aforementioned comments that in no uncertain terms: “This club will win the Premier League”. And they did in 2011/12.

In 2009, Eriksson’s successor Mark Hughes made it publicly clear what the expectations were for him, stating: “I expect us to be challenging for the Champions League”, and a decade after his takeover, with three Premier League titles, three League Cups and an FA Cup to show for their contribution to the club, the determined investor announced: “We are only halfway up our Everest” — drawing attention to that elusive European Cup that had remained just out of their reach. Until Saturday night, that is.

It took just under 15 years, but Sheikh Mansour’s project has finally delivered the trophy he’s clearly coveted the most since investing in the blue part of Manchester — the UEFA Champions League. No longer do City need to be concerned about their fair play record in the hope it delivers European football.

On the contrary, their Financial Fair Play record and the 115 pending charges against them loom as an elephant in any room praising the team’s achievement.

Nevertheless, this analysis won’t delve into the club’s accounts; we’re not the guys who can tell you much about that side of things. This will be a tactical analysis of Manchester City’s 1-0 UEFA Champions League final win over Internazionale.

The losing side were the reigning Serie A Champions in 2008 under Roberto Mancini when City’s takeover occurred, remained Italy’s top dogs in the following two years under José Mourinho, completing a famous treble in 2010, but fell down the pecking order for much of the 2010s when City rose to prominence in their respective domestic league.

It took until 2020/21, under Antonio Conte, for Inter to return to the summit of Italy’s top flight, where Simone Inzaghi has largely kept them fighting for the past couple of seasons, achieving a second-place finish in 2021/22 and a third-place finish in 2022/23, with the promising 47-year-old coach delivering two Coppa Italia trophies and two Supercoppa Italiana triumphs for I Nerazzurri.

The Lazio legend had a seven-win streak in finals as a manager heading into Saturday’s clash with City that has now been broken. But a 1-0 loss to Pep Guardiola’s major money machine is hardly something to be ashamed of.

In fact, given that Inter’s squad (€534.45m) is valued at just over half of what City’s squad is valued (€1.05bn) according to Transfermarkt, the fact that Saturday’s final was a very even game, for the most part, is something of a feather in Inzaghi’s cap. He, his coaching staff and his players can hold their heads up high after their performance in a game where they were universally considered heavy underdogs.

This tactical analysis piece will provide an analysis of the tactics and strategy employed by both teams in Saturday’s fixture to shine a light on how the game played out and why. We’ll analyse key aspects of both teams’ respective approaches, looking at both teams in possession and how their opponent set up against their offensive methods, before going on to compare the two teams’ defensive styles in detail. Strap in and, hopefully, enjoy the ride as we attempt to tactically dissect this game.

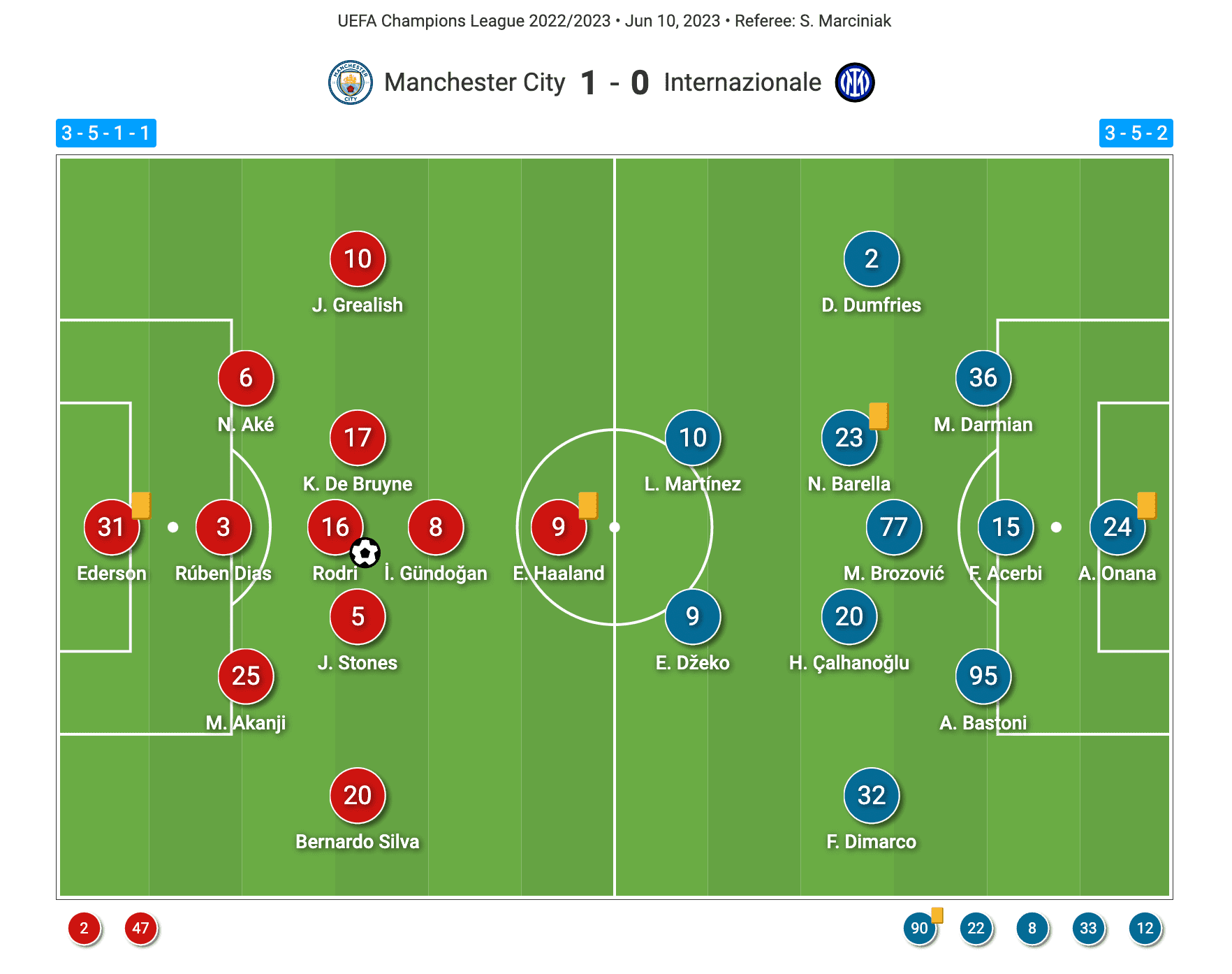

Lineups

Before we get too far ahead of ourselves, we need to take a look at the two teams’ lineups for this game (see figure 1).

Starting with the eventual winners, City started with Ederson Moraes in goal, while Manuel Akanji (right) Rúben Dias (centre) and Nathan Aké (left) were the three centre-backs deployed just in front of him.

Rodri played at the base of City’s midfield diamond behind Kevin De Bruyne (left), John Stones (right) and İlkay Gündoğan (centre). Meanwhile, Bernardo Silva (right) and Jack Grealish (left) lined up on the wings as Erling Haaland was deployed as the centre-forward.

City made just two substitutions during the game, the first of which was forced in the 36th minute as homegrown Phil Foden came on in place of De Bruyne due to an apparent hamstring injury. City’s second sub was Kyle Walker, who replaced Stones in the 82nd minute.

As the image above shows, City lined up in a 3-diamond-3 shape for the majority of this game, though this shape was used solely in possession. They switched to more of a 4-4-2 for large parts of the game out of possession (De Bruyne/Foden joined Haaland at the top while Stones slotted in at right-back to create this shape) and a 4-2-3-1 in the latter stages of the game, with the attacking midfielder just dropping slightly behind Haaland rather than playing beside him.

As for Inter, their 3-5-2 shape was comprised of André Onana in goal behind Matteo Darmian (right), Francesco Acerbi (centre) and Alessandro Bastoni (left) at centre-back. Denzel Dumfries lined up at right wing-back while Federico Dimarco made his presence felt at left wing-back.

Marcelo Brozović was at the base of Inter’s midfield behind Nicolò Barella (right) and Hakan Çalhanoğlu (left), while Lautaro Martínez played just off of Edin Džeko as Inter’s strike partnership.

Romelu Lukaku came on for Džeko as Inter’s first sub in the 57th minute — another forced change due to injury. Shortly after City’s 68th-minute goal, Inter made another couple of changes in the 76th minute, as Robin Gosens and Raoul Bellanova took to the field in place of Bastoni and Dumfries, respectively, giving Inter fresh legs on the wings with both subs moving out to the wing-back positions.

I Nerazzurri’s last two changes happened in the 84th minute; Henrikh Mkhitaryan took over from Çalhanoğlu while Danilo D’Ambrosio’s appearance ended Darmian’s Champions League final.

In possession, Inter lined up similarly to this, except their goalkeeper, Onana, played a vital role in stepping out into the middle of two centre-backs, meaning one centre-back pushed up into midfield alongside Brozović. This left I Nerazzurri with a 3-2-4-2 shape in possession from build-up, including the ‘keeper in the numbers.

Manchester City in possession versus Inter out of possession

Without further adieu, let’s kick on with the analysis. To start with, we’ll take a look at how the newly-crowned European champions played in possession and how Inzaghi’s side approached the game out of possession.

As mentioned above, City lined up in a 3-diamond-3 shape in possession, with Rodri playing at the base of midfield. The 26-year-old Spaniard who joined City from Atlético Madrid in 2019 was absolutely key for City’s attack throughout the game, while Inter’s success in preventing Guardiola’s side from playing through him was a major factor in their bright start to the final.

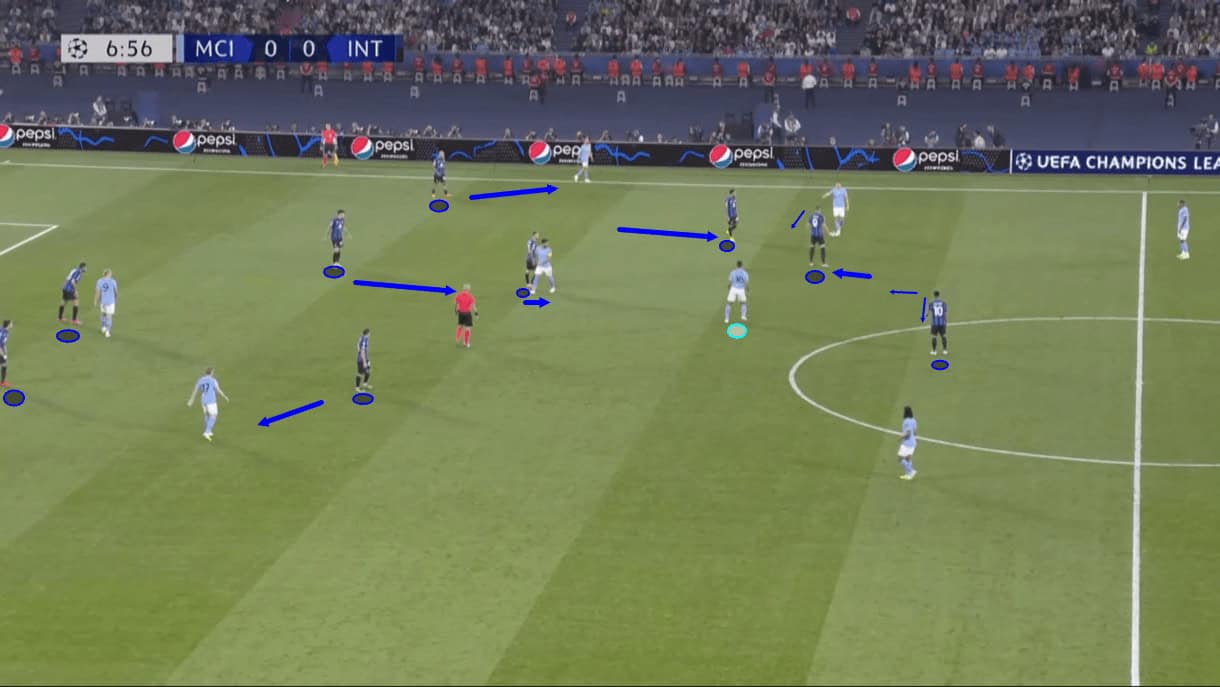

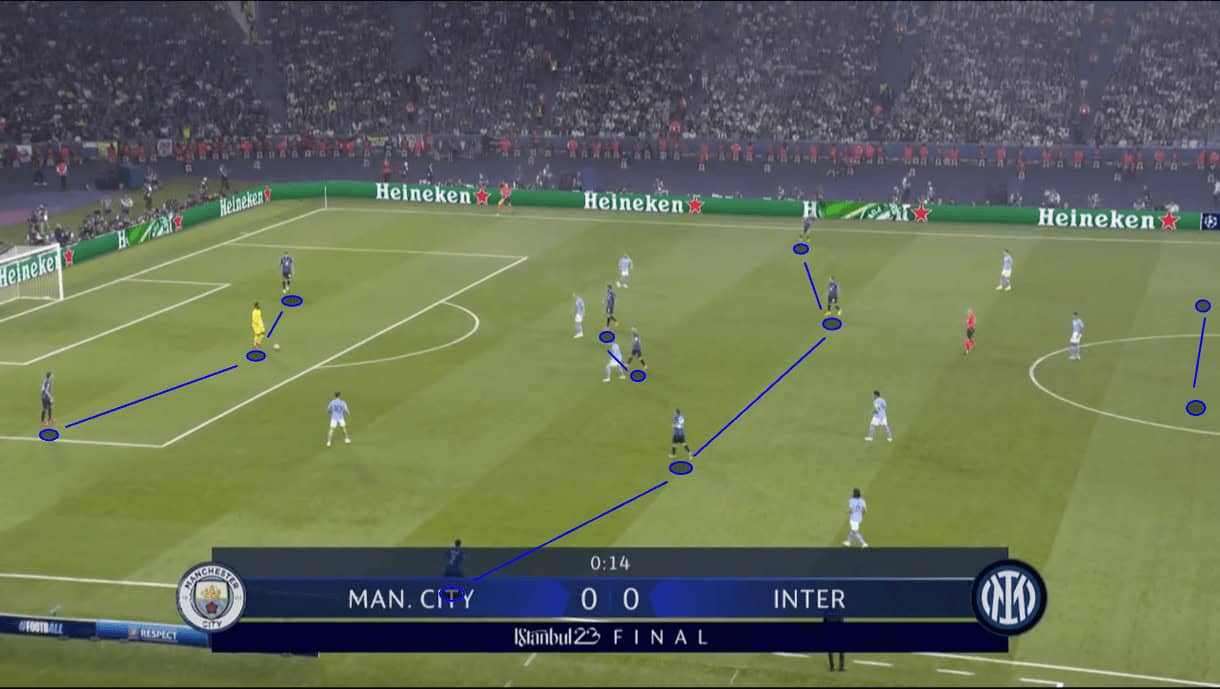

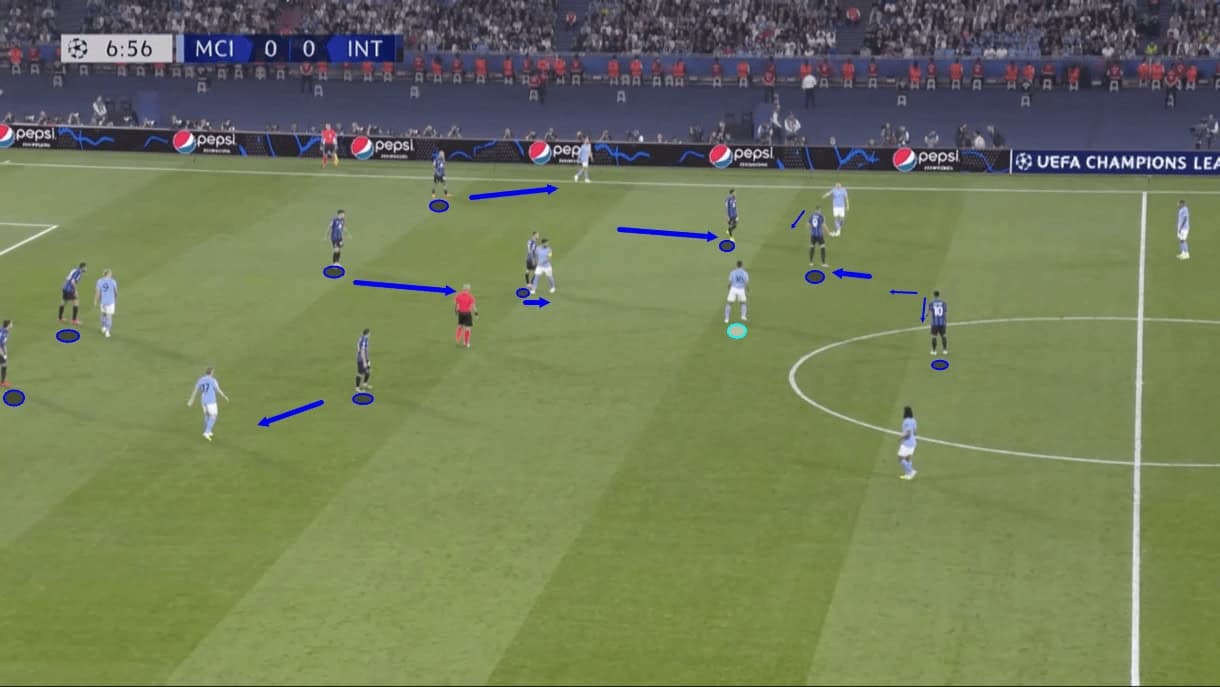

Figure 2 shows how Inter set up defensively in the early stages of this game and successfully prevented City from utilising Rodri to the extent that they’d have liked. Setting up largely in a mid-block, Inter’s wide central midfielders pressed their light blue counterparts fairly aggressively. Brozović marked the central attacking midfield option while the ball-far midfielder retained access to the City midfielder near them.

Now, if you’re counting, that’s three Inter shirts but four City shirts, so City had the central overload, right? This is where Inter’s centre-forwards come in. Džeko (later Lukaku) and Martínez had a very important job to do in the build-up/ball progression phases. They had to screen Rodri like their lives depended on it, remaining in the passing lane between him and the ball carrier, ensuring City didn’t have a clear, attractive option in the 26-year-old deep-lying midfielder.

Above, we see Džeko performing his screening job excellently while Martínez retains access to Rodri while blocking off the pass across the field to Aké at the same time.

I Nerazzurri’s pressing was particularly impressive in the early stages of this game and forced City to play with a much slower tempo than they’d ordinarily want to play. They successfully disrupted the EPL champions’ flow with their very effective defensive setup.

This defensive approach took a lot of energy out of Inter’s midfield and forwards, however, especially as City kept so much of the ball in the opening half an hour when Inter’s defence was at its brightest. If Inter were to capitalise on their solid defensive tactics, this early period really would’ve been the time to do it but with City retaining 70% of the ball between the 16th and 30th minute, both physical and mental fatigue inevitably set in for Inzaghi’s men.

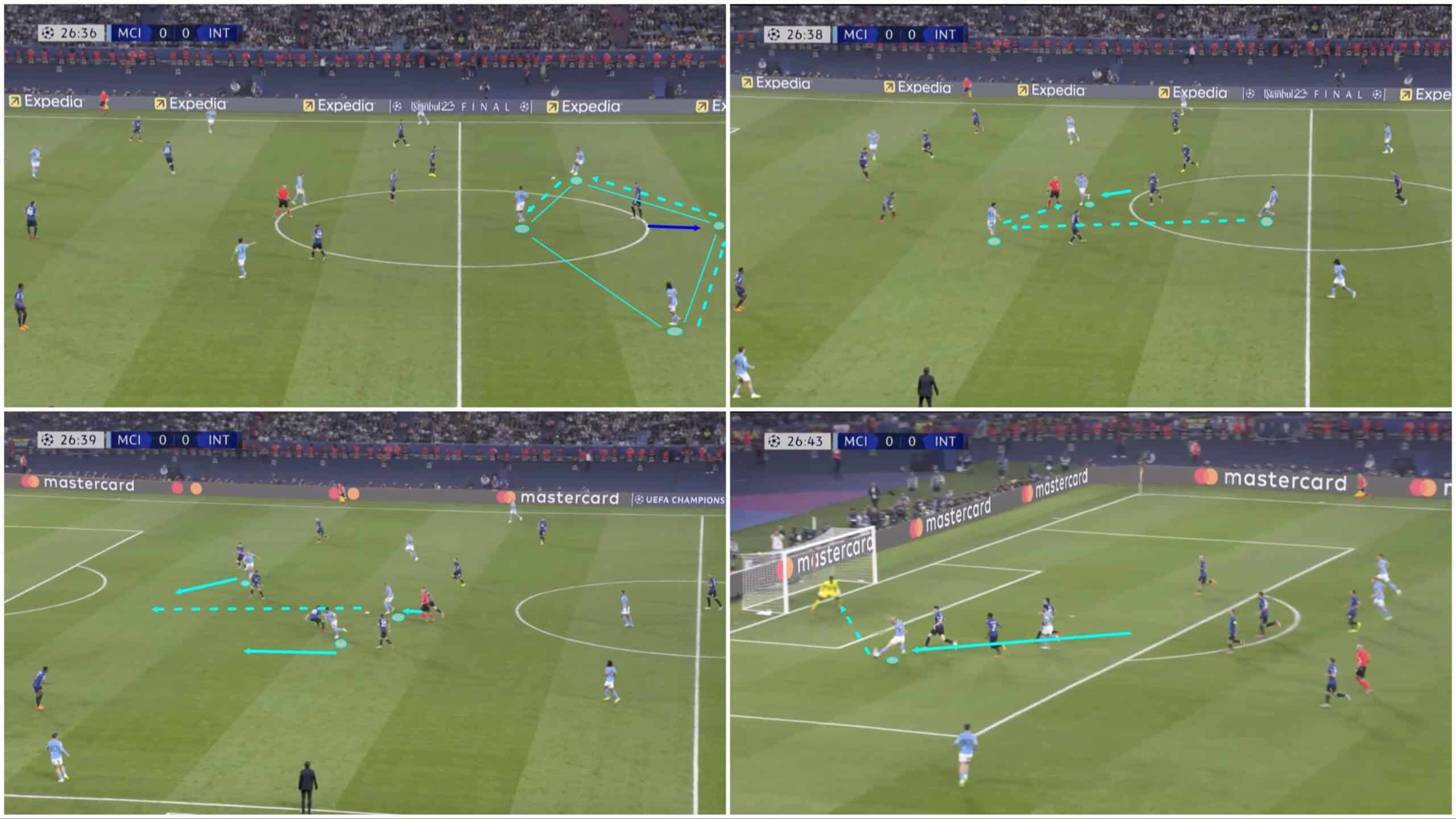

City slowly but surely started finding a path into Rodri more and more as the first half wore on. We see an example from the 26th minute above, where City’s initial diamond (the three centre-backs with Rodri at the tip) manipulated 37-year-old Džeko’s pressing, with Aké forcing him out with a pass back to deepest Dias, allowing the Portuguese centre-back to intelligently play the ball around the striker with a ball out to Akanji who could quickly slide it through for Rodri. Success.

Rodri’s technical ability and vision allowed him to receive and quickly pick out a great pass into Gündoğan’s feet, as the German midfielder drifted off his marker’s shoulder. Gündoğan’s movement was another important theme to City’s play through the centre in this contest — even when Rodri was marked out, Gündoğan provided an option by dropping off, at times, making himself a real handful for Inter’s midfielders to cope with. However, he was at his best when drifting away into space behind Inter’s midfielders just on the edge of the final third as we see in this example.

The City captain neatly laid the ball off for his Belgian midfield teammate De Bruyne, who slid it through for Haaland, creating a solid goalscoring opportunity. This provides an example of how Rodri was so useful for his side when they found him in his central position. The midfielder’s vision and technical quality are so lethal from that deep position that he can improve his team’s positioning and threat level very quickly. So, the battle between City trying to feed him and Inter trying to cage him was extremely important.

Inter’s success at caging Rodri is a major reason why City struggled to create many chances and Haaland was kept so quiet. It’s difficult to defend against the big Norwegian 1v1 or even 2v1. Even cutting off the supply to him is tricky, so Inter went with cutting off the supply to the supply — defending higher out of pragmatism. It was an intelligent approach that delivered reasonable success for I Nerazzurri.

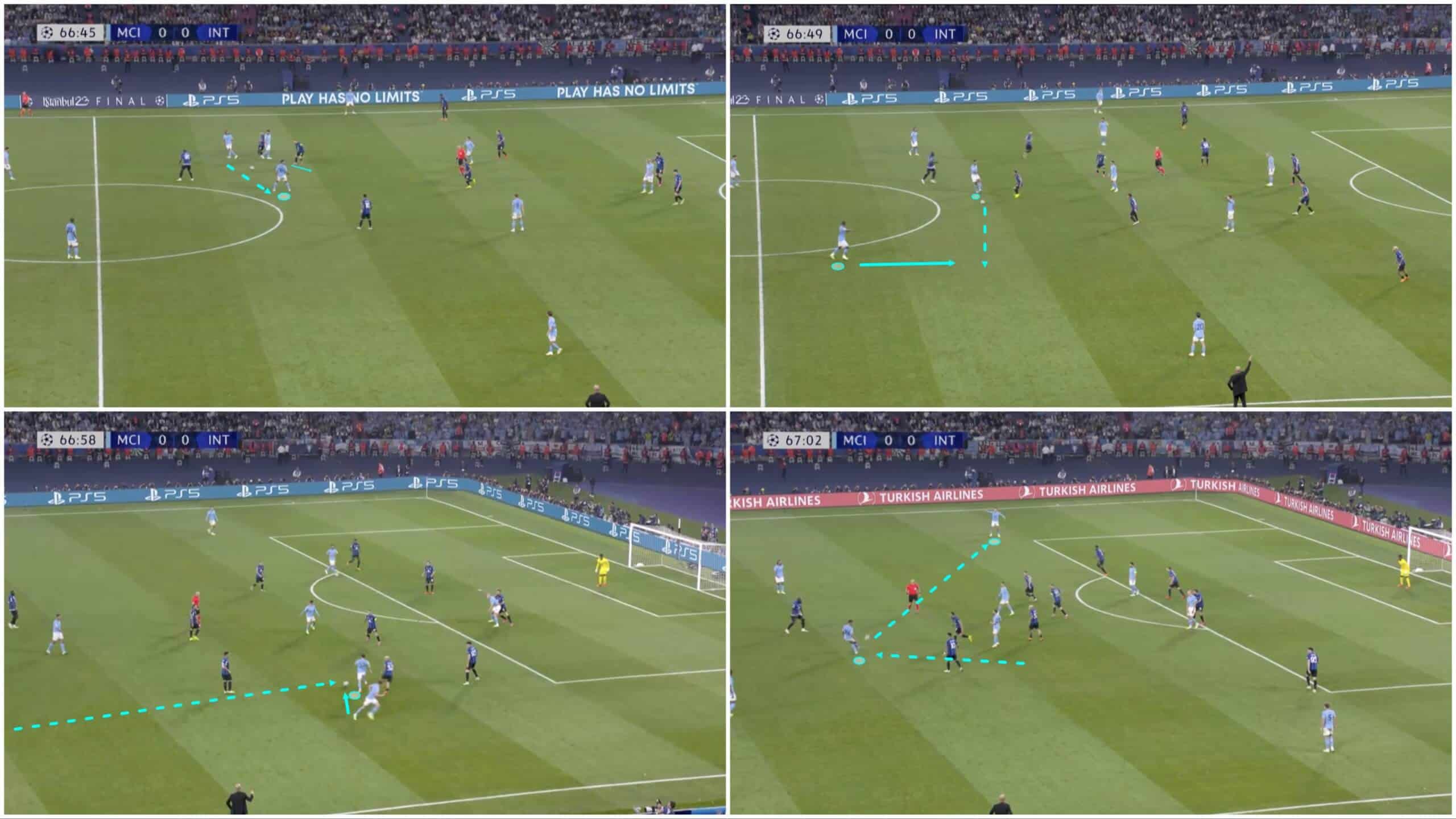

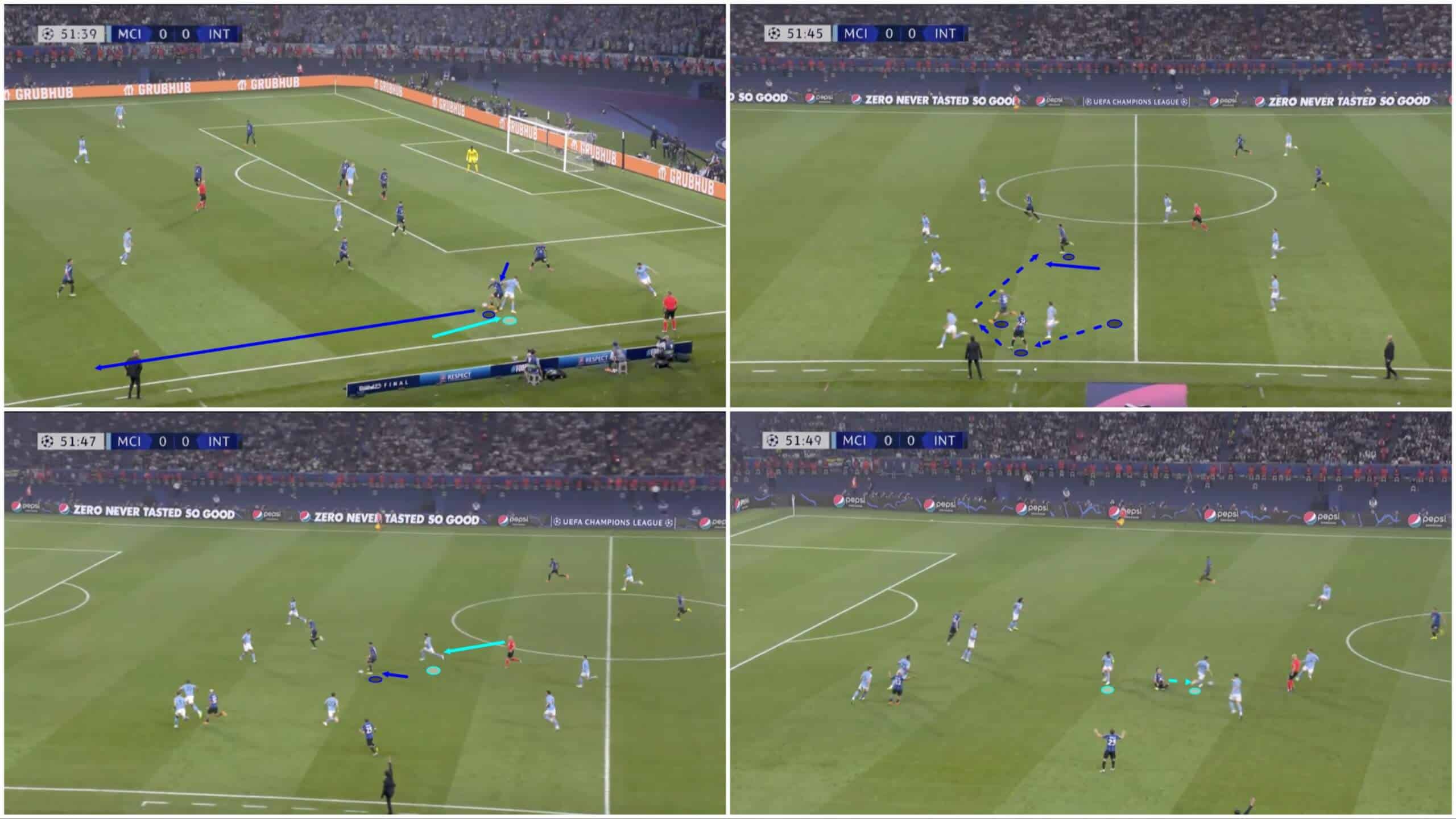

In the later stages of the game, Inter got more and more fatigued — again, both physically and mentally — as City continued passing them to death. Inter’s intensity was at its lowest on either side of half-time and above, in figure 4, we see an example of City’s possession play from this period when they really had a grip on the game, with this example coming just before Guardiola’s men broke the deadlock and scored the vital goal of the game.

We see how it became easier to find Rodri from the wider positions we saw Inter desperately blocking off back in figure 2 in the early stages of the game. As things progressed, it became harder and harder for Inter to continue to maintain the same physical and mental energy while fighting this battle, as City relentlessly continued pursuing progression through Rodri.

With Inter slowly backing off and becoming pinned inside their own third, it left room for City’s wide centre-backs (in this case, Akanji) to break further forward, helping them to add another element to City’s progression phase. Rodri remained free in the centre as City progressed beyond him, forcing Inter’s defence back, making him a valuable option in spreading the ball around the final third.

Passes like the one we see in the bottom-right image above served to force open gaps in Inter’s defence that Guardiola’s men wouldn’t need a second invitation to probe into.

John Stones has become a revelation in the middle of the park for Guardiola and passages of play like the one shown in figure 5 give a great example of why this has been the case. Here, we see Stones taking the ball down well with his chest as he receives in the middle of the park, behind Inter’s central midfielders who got drawn upfield by the other midfield threats. The potential to create overloads like this one was a major reason for Guardiola’s choice of setup in this game.

After taking the ball down, Stones was able to link up with Gündoğan and Rodri to play through Inter’s midfield and set himself up to drive the team forward as we move on from figure 5.

Stones didn’t become less involved in advanced areas in the second half. If anything, he actually enjoyed more freedom to roam, being frequently found in the right half-space, occasionally being the second-furthest forward City player behind Haaland!

Stones exhibited some really impressive dribbling quality on occasion, demonstrating his quality and ability to increase his side’s threat via ball-carrying into more dangerous areas than where he initially receives. In this case, the 188cm Englishman skipped past two Inter challenges on his way into zone 14 from where he could play the ball to a more orthodox attacking threat for City in Gündoğan.

The 29-year-old was very much a major positive for City in possession on Saturday night. All in all, City’s midfield setup was different to what we’ve become accustomed to this season but through relentless perseverance, they found ways through Inter’s solid defence to create goalscoring chances as the Italian side became fatigued.

Still, Inter did a very nice job defensively, limiting City to one shot from 21 positional attacks, per Wyscout — far below their usual standard — and City’s midfield perhaps could’ve been set up to attack Inter more efficiently than they were.

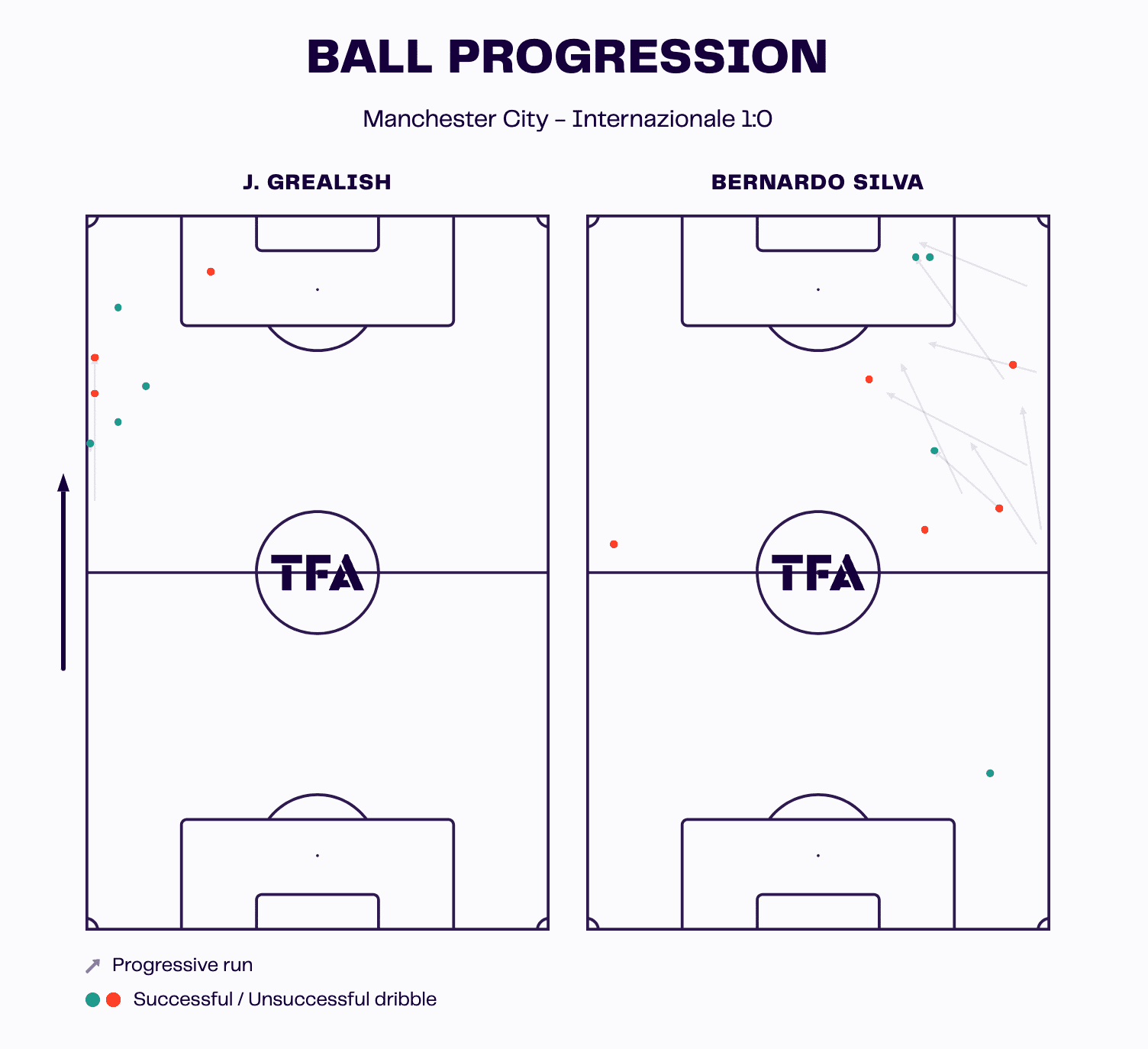

City’s wingers were very active dribblers throughout Saturday’s final. Not all of these dribbles came off successfully but their persistence and bravery to try and take the game into their hands and drive at Inter’s backline was rewarded on some occasions, resulting in decent penetrative runs probing into the opposition’s box and creating some trouble for the defence.

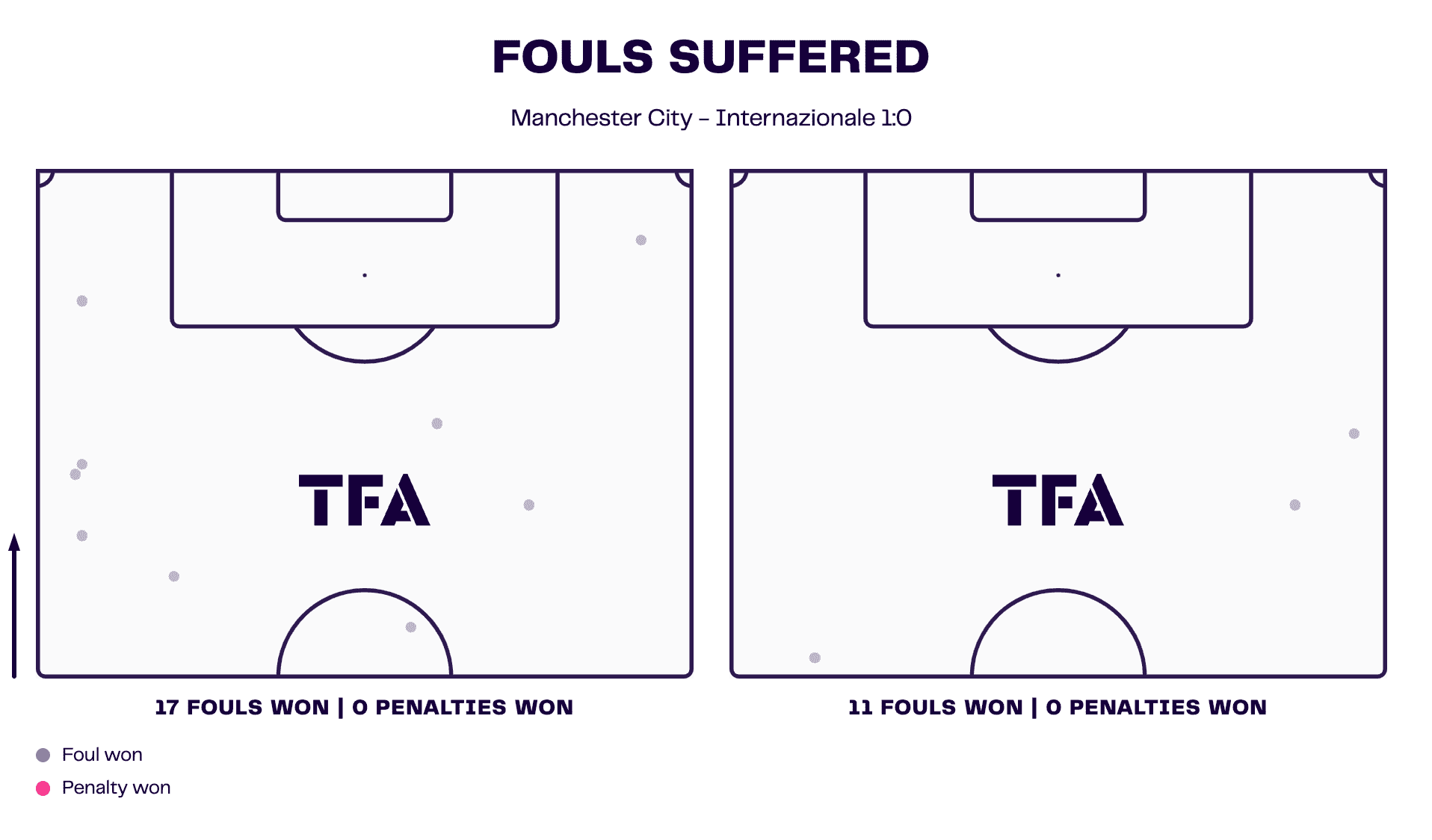

Where the two teams significantly differed in their dribbling was how City’s wingers successfully drew fouls a lot more effectively than Inter’s wingers. This is illustrated in the visualisation above, with City’s fouls won on the left and Inter’s fouls won on the right.

Not only did City draw more fouls throughout the game but they drew more fouls in advanced areas of the pitch, where the wingers would be found, compared to Inter who drew just three in the opposition’s half, per the visualisation.

This comes down to things like body positioning between the defender and the ball which City’s wingers excel at. There aren’t many wingers in the world better at drawing fouls effectively than these two, which was a helpful skill for City at times in creating free-kick opportunities and buying their team some time to regroup inside the opponent’s half, as well as shutting down potential counterattacks by tactically winning fouls, rather than committing tactical fouls of their own.

The wingers’ performances weren’t perfect for City on Saturday — at times, their dribbling was a bit ineffective and also their pass reception was not the best. With the centre congested, they sometimes dropped to receive out on the wing in deep positions from the centre-back, but this is a pass that Guardiola would likely try to avoid as his wingers would easily be followed by the opposition wing-back, prevented from moving forward or even turning to face the opposition’s goal in a not-so-threatening position and ultimately end up getting dispossessed out wide in the middle of the park.

However, their contribution on the ball was significant in any event, as they constantly added threat for their side through their dribbling bravery and technical quality, acting as key outlets for final third progression for Guardiola’s men.

Inter in possession versus Manchester City out of possession

On the flip side, our next section of analysis focuses on Inter’s performance in possession and City’s approach without the ball.

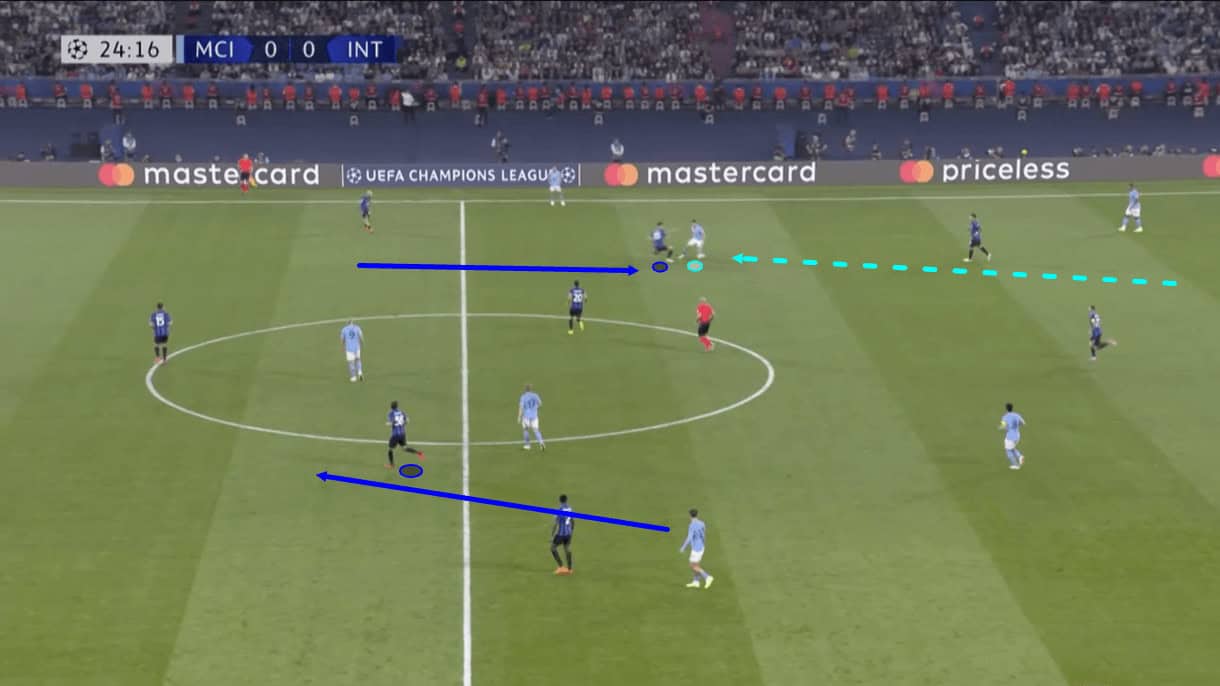

As mentioned earlier, Onana played a key role in possession for Inter, particularly in the build-up. His presence in the middle of the back three allowed a centre-back to step up into midfield alongside Brozović, creating a box midfield for I Nerazzurri that occupied City’s striker and advanced midfielder (De Bruyne, here).

If City’s deeper midfielders (Rodri and Gündoğan) stepped up to mark the two more advanced Inter midfielders, this would leave space for Martínez to drop into and exploit in between the lines. If they stayed deep, they allowed the two midfielders to enjoy some space in the middle of the park. This highlights one of the many benefits of having a goalkeeper that’s so comfortable on the ball, like Onana.

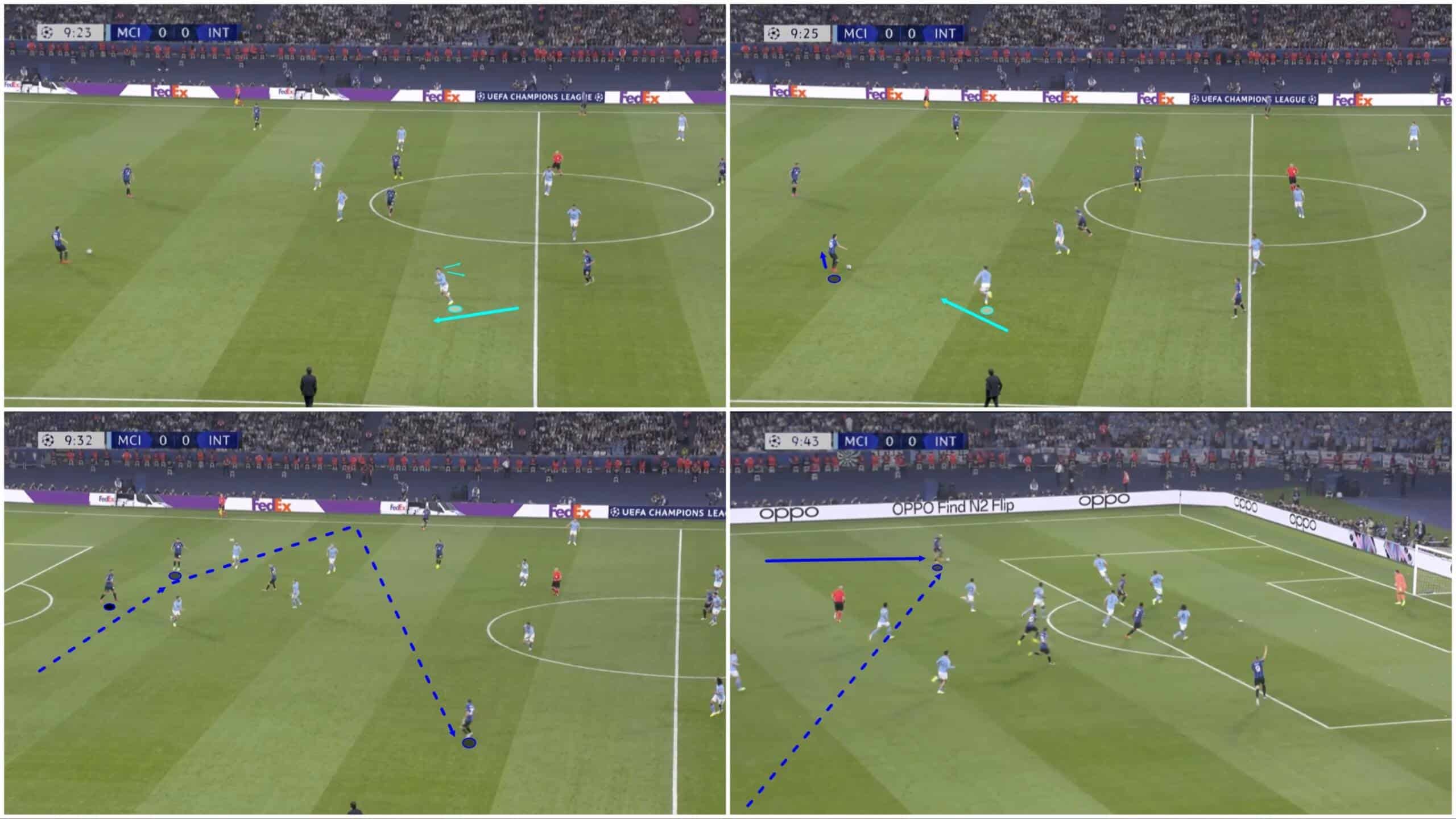

As we see in this example, City’s wingers, Grealish and Silva, often came quite narrow when City were in the high-pressing phase. This was designed to make Inter’s centre-backs uncomfortable and either force an error or force an uncontrolled long ball that City could win back possession from in a deeper area. However, Inter consistently dealt well with this pressing threat from City and used this narrow positioning from the wingers to their advantage in the build-up and ball progression phases.

We have an example of Inter playing over and beyond a Grealish press in figure 10. The left-winger checked his shoulders to ensure he wasn’t leaving anything blatantly obvious open as Inter played the ball out to the right centre-back. Once he felt comfortable, he jumped and pressed the right centre-back aggressively, increasing the intensity of his press after Darmian took the touch we see in the top-right quarter which closed his body off for the pass out to the right wing.

However, this was a very intelligent move from Inter’s back three. Darmian played the ball across his backline and as it arrived with the left centre-back, with Grealish now drawn all the way into the centre, the left centre-back casually lifted the ball over City’s press, out to a free man on the right wing who Aké must either come well away from his centre-back partners to close down or allow to have a lot of space to work with in midfield.

As play progresses, the ball ends up with the left wing-back, Dimarco, in the final third, from where Inter can put an inviting ball into the box.

This attacking move was possible because of how well Inter dealt with Grealish’s pressure. They remained calm and composed on the ball at the back and found a very effective solution to the pressure.

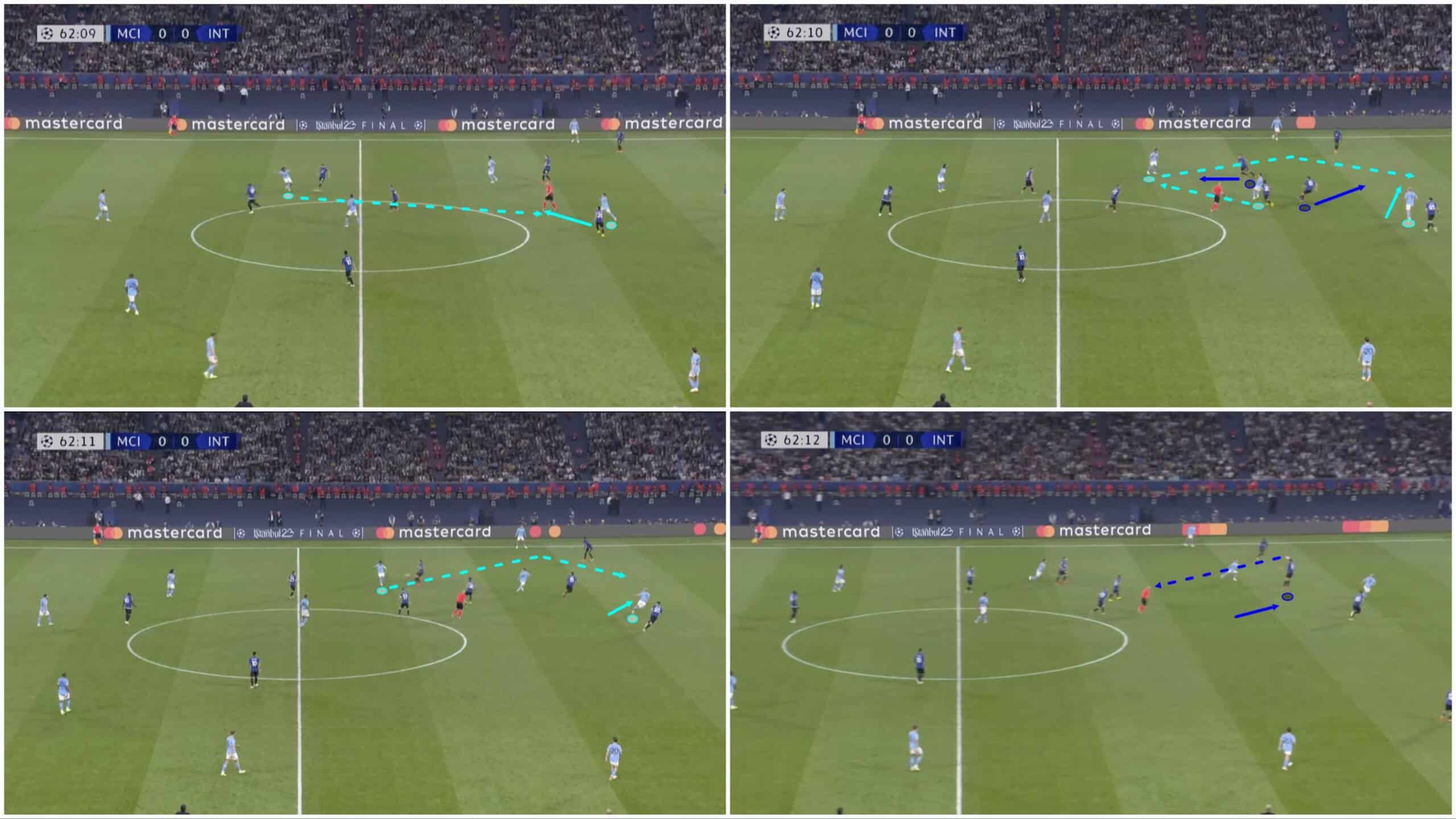

This was a common theme throughout Saturday’s game, as the four separate images in figure 11 showcase. Time and time again, Inter drew City’s press high and found a way past them after some composed play around the back. Most of their passes went over the press and out to the wing but as the bottom-right image above shows, they also didn’t shy away from playing the ball over the top and down the centre for a Nerazzurri shirt to take it down.

While this tactic required great composure and technical quality on the ball to execute effectively, Inter didn’t make many mistakes in this game, committing just two errors on the ball leading to an opponent shot. This is compared to a nervous and sometimes unconcentrated Man City team who committed seven errors leading to opponent shots.

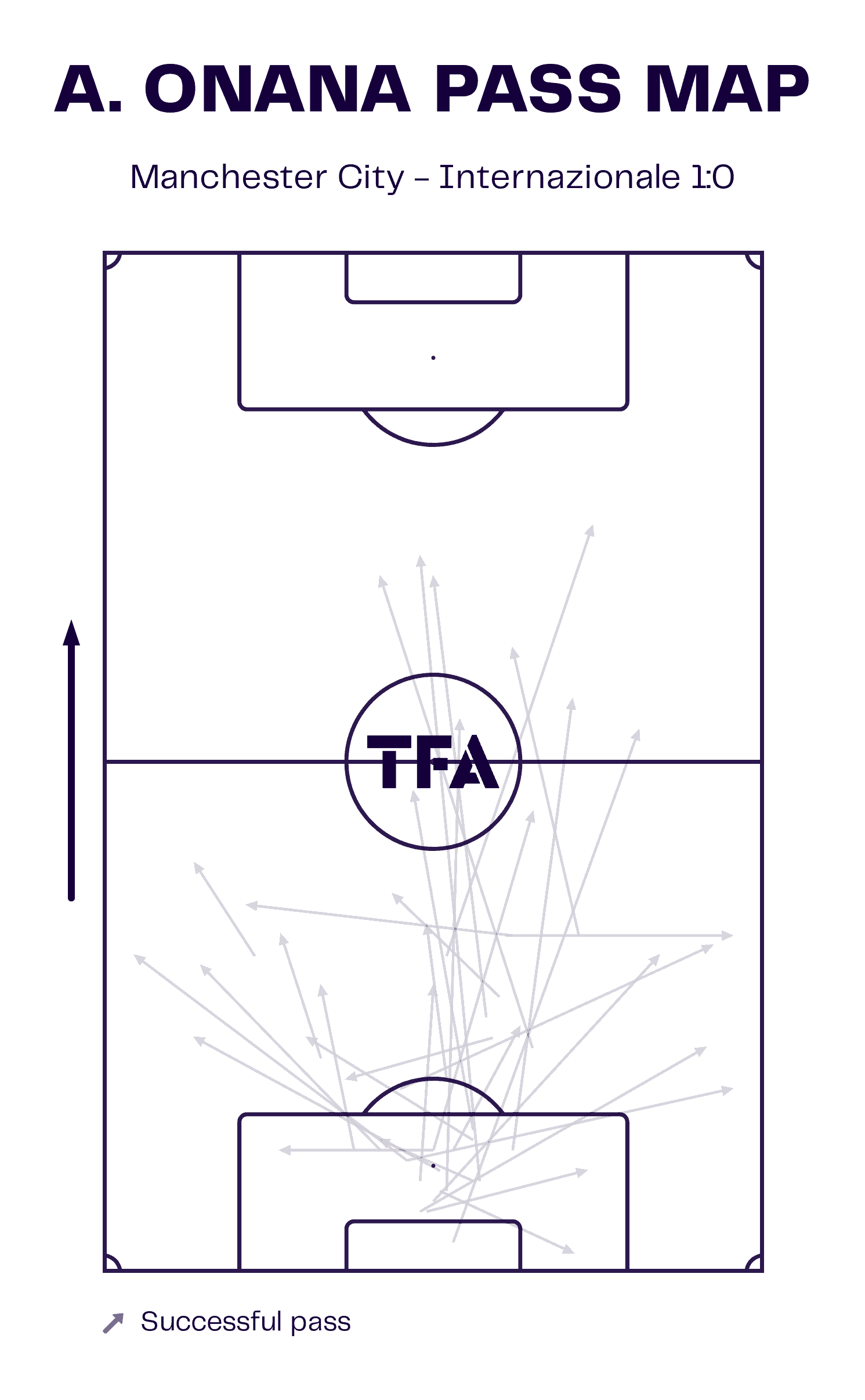

As the image above shows, ‘keeper André Onana again came in clutch in these situations, helping his team beat the opposition’s press regularly via his vision and technical long-passing quality.

Figure 12 shows Onana’s pass map from the Champions League final. Plenty of the balls went long, both centrally and out to the wings. However, these weren’t just hoofed long balls to get it to safety, Onana’s passes were generally calculated, which his 86% passing accuracy rate would back up.

The Cameroonian stopper represented a real weapon for the Serie A side from his deep position, exhibiting the ability to launch balls with great accuracy from a difficult-to-press position. Onana offered so many benefits to his team on the ball this past weekend that, at times, it was like having an extra player for Inter, who maintained a slightly faster-than-normal tempo to their play on Saturday.

In figure 13, we see an example of one occasion when Onana’s long passing quality helped Inter to quickly generate a decent goalscoring chance on Saturday, as Onana found Lukaku’s head just moments after the Belgian forward was introduced, with the on-loan Chelsea man flicking it on to the right wing-back Dumfries.

As we pick up play in the bottom-left image, we see that Onana’s pass to Lukaku’s flick-on and Dumfries’ overlapping run created a 3v2 overload for Inter. However, Akanji positioned himself excellently and managed to save his tea from going a goal down with a critical interception and clearance.

This was a great move from Inter that showed a couple of ways they could harm City.

Firstly, their attackers had the ability to hurt City with their strength. Whether it was Lukaku as we saw here, Dumfries who often acted as a wide target man in this game up against Aké, Džeko or even Martínez who used his hold-up play and strength to get the better of Akanji on a few occasions, Inter demonstrated a solid ability to hurt City’s defence in 1v1 battles thanks to their strength but didn’t make enough use of this throughout the full 90 minutes, perhaps shying away from too many direct balls forward for fear of giving it straight back to City.

We saw more of these direct balls to create physical 1v1 duels after City scored, which ended up being Inter’s most productive period of the game in terms of chance creation. This tactic, combined with possibly some nerves from Man City, forced Guardiola’s side back to defending on the edge of their box for periods and even then, Inter’s size and strength advantages delivered decent chances for the Italian side — for example, with Robin Gosens getting forward and leaping over Bernardo Silva at the back post to nod the ball across goal for Lukaku to try and convert from — that they were just unfortunate not to score.

Had they relied on this aspect of their game a bit more, perhaps more good chances could’ve fallen their way and who knows how the game would’ve turned out?

Secondly, Inter could’ve targeted the space left open on the right side of defence behind the wandering John Stones more often. It was difficult for the 29-year-old right-central midfielder to get back and recover into his right-back position out of possession, which left Akanji fairly exposed on some occasions. This time, the Swiss centre-back dealt with the issue well but on other occasions, he floundered more and this was a weakness in City’s transition to defence that could’ve been greater exploited.

In any event, we saw how Inter could trouble City via their ability to draw the press high before exploding behind them and their physicality in 1v1 duels with the English team’s centre-backs.

Defensive styles

Let’s go into a little bit more detail on the out-of-possession side of things as we move on into our next section, defensive styles, aiming to compare and contrast the two teams in defensive phases.

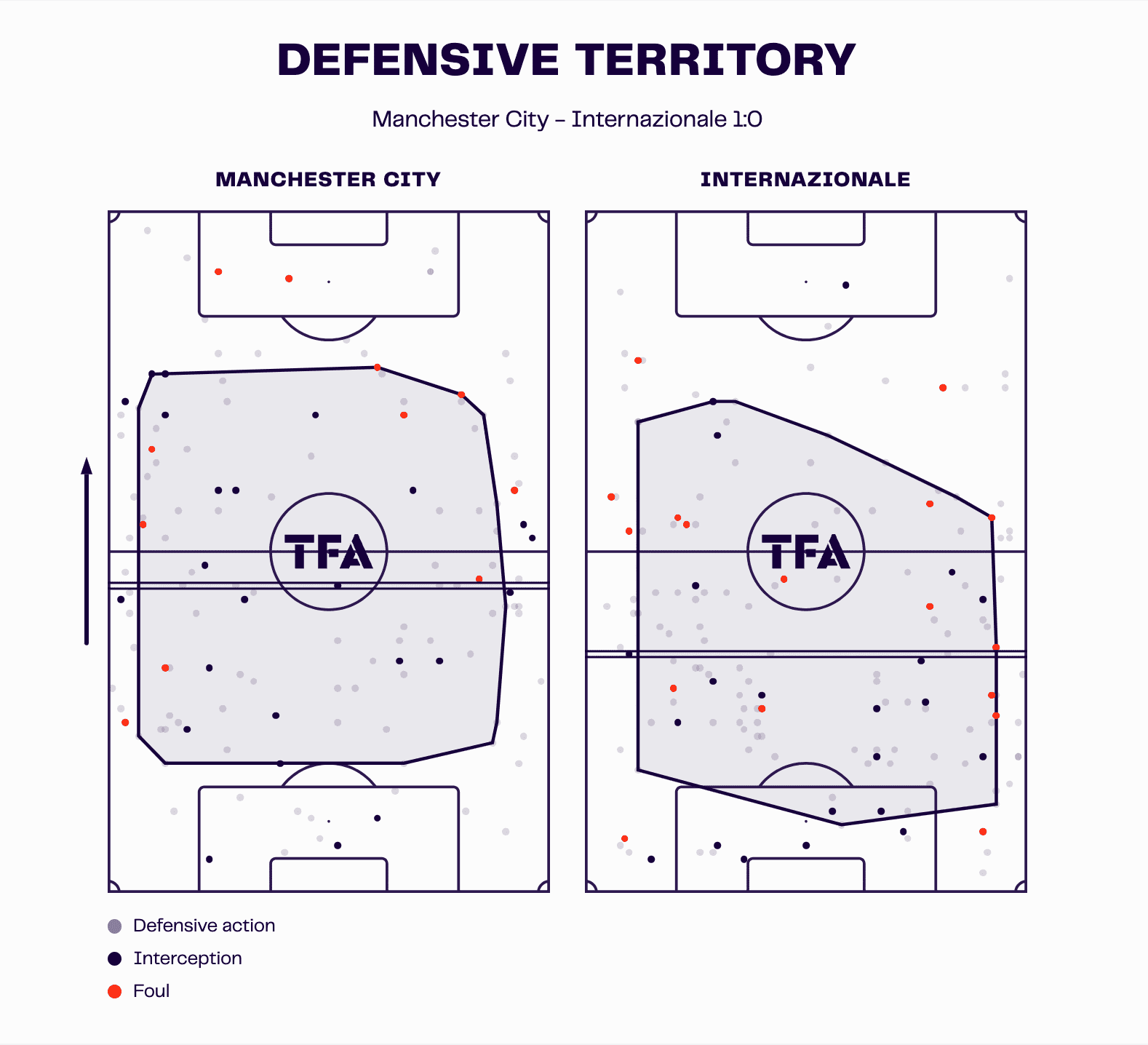

Starting out with figure 14, here we can see both teams’ respective defensive territory maps from Saturday’s game. Firstly, it’s obvious that City’s centre-backs tended to sit a fair bit higher than Inter’s centre-backs in Saturday’s game, as the average defensive line height shows on these maps.

City had a little bit more joy defending on the left than they did on the right, with Rúben Dias frequently stepping out to clear away balls and intercept passes to the left, where Gündoğan also roamed. Inter found a little bit more joy on their own left wing, attacking the right side of City’s defence.

Inter’s defence was quite balanced across the pitch; like City, the left was strong with Dimarco and Bastoni committing interceptions and stepping out to confront City attackers but Barella made the right very difficult to play through via his positioning and work rate. Furthermore, Brozović made himself a useful weapon in the centre of the pitch, shifting around and breaking up play via his positioning where necessary.

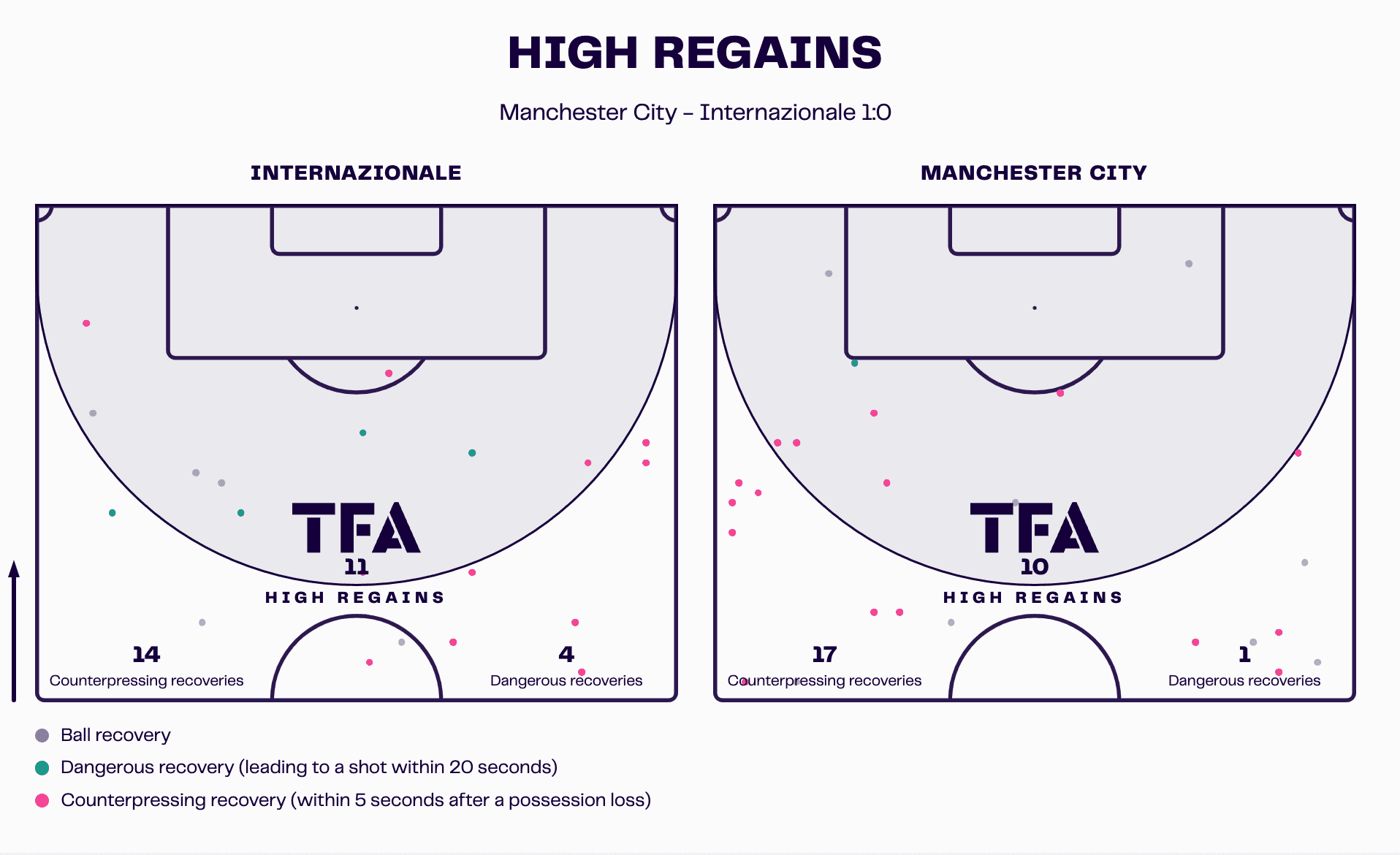

Both teams made a similar number of high regains in Saturday’s game with Inter slightly edging it in total. However, the types of regains they made were quite different to one another. In City’s case, they made just one ‘dangerous recovery’, indicating that they weren’t great at turning their high regains directly into goalscoring opportunities.

Inter, meanwhile, made four dangerous recoveries and as we touched on earlier, they were good at capitalising on City’s unforced errors at the back and turning them into shooting opportunities for themselves.

At the same time, City were slightly more effective at counterpressing, making three more counterpressing recoveries than Inter managed in this game — this was really where Guardiola’s side shone in a defensive sense.

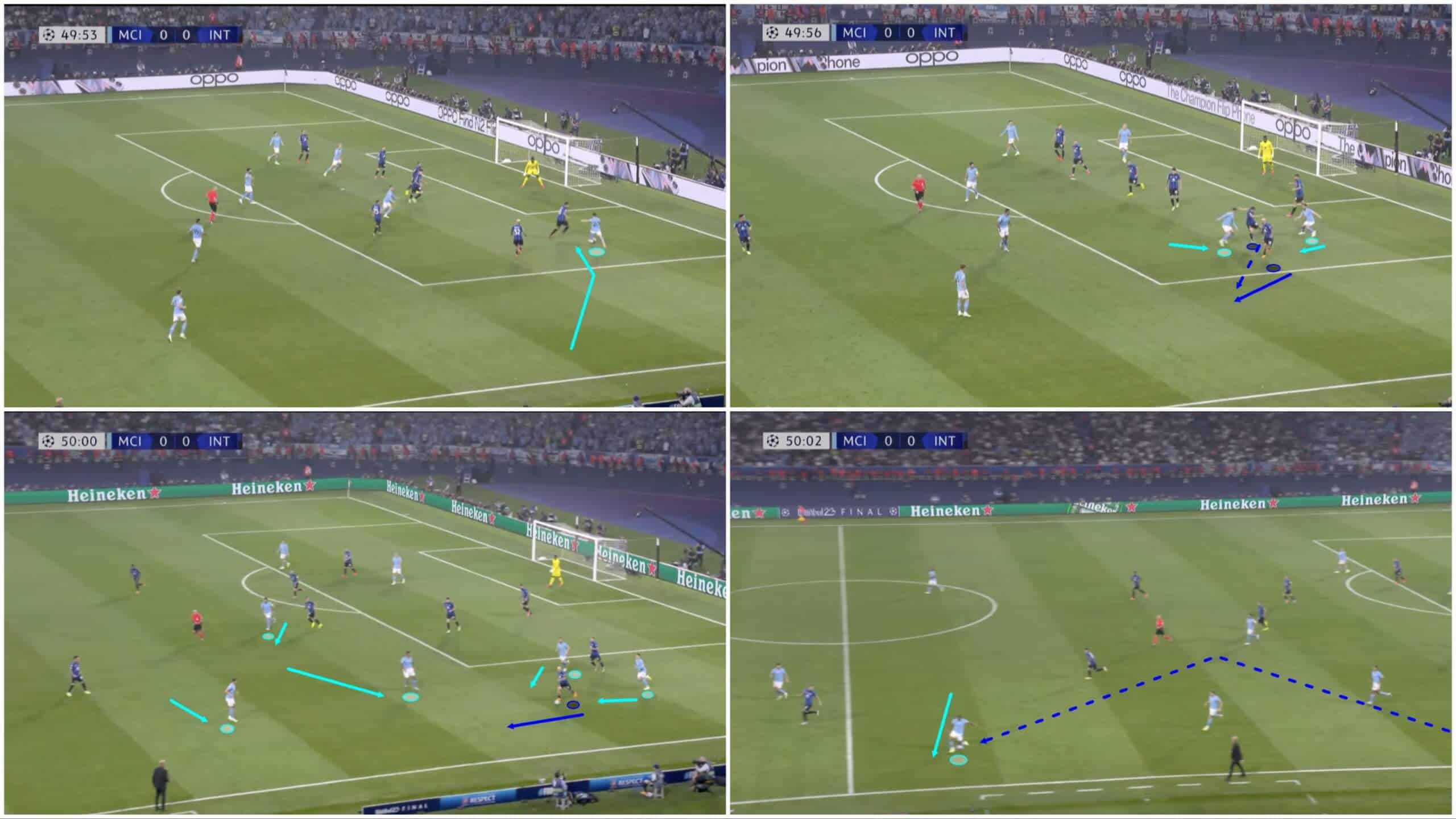

We see an example of the City counterpress here in figure 16. As Silva approached the box from the right wing, he was smothered and dispossessed by Bastoni, who knocks the ball out to Dimarco to try and carry it away from danger.

Immediately, the left wing-back is being swarmed by City shirts with Silva and Foden — Silva’s nearest cutback passing option from the previous attack — moving to close the Portuguese winger down.

Dimarco begins moving upfield but the space around him is soon congested with the aforementioned duo still in hot pursuit from behind, while Rodri has advanced to close the space into the centre and Stones has advanced to cut off a passing lane into the centre too. If Dimarco tries to go himself from here, he’ll be closed down and dispossessed by one of the two midfielders patrolling the central space and positioning themselves well to control the wing-back’s movement.

The Inter ball carrier attempts a long ball forward to the striker that’s ultimately intercepted by Akanji, allowing City to regain the ball just inside the opposition’s half and kickstart an attack from here not so long after losing the ball (about nine seconds, in fact).

City retained high energy to counterpress like this throughout the game. Guardiola managed his side’s stamina well to ensure their defensive strategy was sustainable for the full game, unlike Inter who seemed to burn themselves out after about half an hour.

In the opening 25-30 minutes, Inter probably enjoyed the best section of the game for either side thanks to their defensive efficiency but they couldn’t sustain this level for 90 minutes, which ultimately cost them. City, in part thanks to their possession dominance, were able to manage their energy a lot better, ensuring their strategy was effective for the whole game, not just a 25-30-minute spell. This made a major difference between the two teams in the middle portion of the game where City really got a grip on things.

We see another example of City regaining the ball about 10 seconds after losing it in figure 17 above. Here, again Dimarco is tasked with leading the counterattack for Inter and he gets into the City half before trying to play into midfield. The pass is played a little too far behind the receiver’s running path, giving City midfielder Gündoğan a chance to recover and dispossess the receiver. Silva then cleans up, leading the counter himself for the English side.

City’s defensive energy over the full 90 minutes, particularly in this middle portion of the game, was vital for their defensive strategy in quickly winning back the ball after losing it.

Inter’s centre-backs defended excellently, in general, in the Champions League final. They worked together very well as a unit and fully earned their success. Take figure 18 as an example; here, City have cut through Inter’s midfield with some incisive passing, creating an opportunity to launch the ball down the left-sided channel and in behind for Haaland to chase.

Darmian, Inter’s right centre-back who’d typically be positioned in this channel, has been dragged out of position by Foden’s pass to Gündoğan. The 33-year-old defender steps out, attempting to close down the German midfielder and block his forward passing space but Gündoğan is too quick and simply plays the ball over the approaching Italian.

However, Acerbi reads the situation well, reacting immediately to Darmian stepping out by dropping into his vacant spot on the right side of defence and intercepting the through pass to Haaland, heading it away from danger.

It was common to see Inter’s centre-backs stepping out to defend aggressively in this game and when they did so, it was imperative that they had cover from their central defensive partners, as Darmian did here in the form of Acerbi.

We have another example of Inter’s wide centre-backs stepping out in figures 19-20. Firstly, figure 19 shows Darmian again stepping up to close down Gündoğan. Just before this image, it looked as though the City midfielder was dropping to make himself available for Aké’s forward pass. However, as the Italian stepped up, he made the pass less attractive and as pressure mounted on the Dutch centre-back, he played it back to Ederson, giving City a chance to recirculate possession on the opposite side of the pitch.

As City ended up out on the right just a few seconds later, now it was Bastoni’s turn to step up as the ball was played to Stones in the right half-space. Inter’s centre-backs were tasked with constantly denying space to any City players receiving with a bit of freedom beside or behind I Nerazzurri’s midfield line. At the same time, Inter’s centre-backs had to be disciplined and mindful of their teammates. See figure 20 for Darmian dropping back as Bastoni stepped out, ensuring Acerbi wasn’t left stranded in a potential 1v1 versus Haaland.

This tactic was risky, bold and brave but it was largely effective at shutting down City’s key playmakers in the half-spaces and central attacking midfield areas.

Conclusion

To conclude this tactical analysis, we hope we’ve made it clear how this game tactically played out quite evenly between the two Champions League finalists. City’s system in possession ultimately paid off even though Inter set up well to defend against them and block off the middle of the park, particularly in the early portions of the game.

Could a different City setup have made life easier for them? It’s quite possible but in the end, this got the job done in a Champions League final as they wore down a well-organised Inter defence, so we can’t be too critical.

The runners-up found plenty of joy playing through City’s press by drawing the light blue shirts high upfield and exploiting the space left open behind them with creative balls launched from deep by the centre-backs and goalkeeper. If they’d leaned a bit more on their direct play to the forwards and creation of physical 1v1s, perhaps they’d have created even more chances as they did late on in the game but either way, they delivered a performance they can keep their heads high about.

Ultimately, we’d say City’s energy conservation proved crucial in their victory as it allowed them to maintain their high energy defensive tactics for longer than Inter, who became fatigued far earlier in the final. This proved critical when it came to sustaining offensive pressure late on in the game.

Comments