In a remarkable month for Spanish football, the Spain Under-19 national team secured the UEFA EURO U19 Championship title nearly two weeks after the senior Spanish national team won the same tournament.

In Windsor Park, Spain defeated France 2-0, setting a new record for the most UEFA EURO U19 titles with 12, surpassing the previous record held jointly with England.

Their opponents in the final, France, were the second-worst ranked in terms of goals against, with seven goals conceded in the tournament, only trailing Denmark, who have conceded nine goals, despite being the best in terms of attacking, scoring nine goals in the tournament.

In this U19 Euro Final tactical analysis, we will explain how each team acted in different game phases and how the opponent replied by adjusting many tactics, showing each team’s strengths and weaknesses in these phases.

Lineups & Formations

Spain used the main 4-2-3-1 formation on paper, which changed to 4-4-2 while defending. GK: Raúl Jiménez Latorre, RB:Cristian David, RCB: Simo Keddari, LCB: Yarek Gasiorowski: LB: Julio Díaz del Romo, RCM: José María Andrés Baixauli, LCM: Gerard Hernández, RW: Dani Rodríguez, AM:Rayane Belaid, LW: David Mella Boullón, CF: Iker Bravo.

On paper, France depended on a 4-2-3-1 formation: GK: Justin Bengui João, RB: Saël Kumbedi, RCB: Jérémy Jacquet, LCB: Yoni Gomis: LB: Aboubaka Soumahoro, RCM: Mayssam Benama, LCM: Valentin Atangana, RW: Dehmaine Tabibou Assoumani, AM: Jean-Mattéo Bahoya, LW: Saïmon Bouabré, CF: Eli Junior Kroupi.

Spain In Possession Vs, France Out Of Possession

Most of the time, Spain had the ball in the progression phase due to France’s mid or low press, so we will start with Spain’s progression and final third against France’s mid and low block.

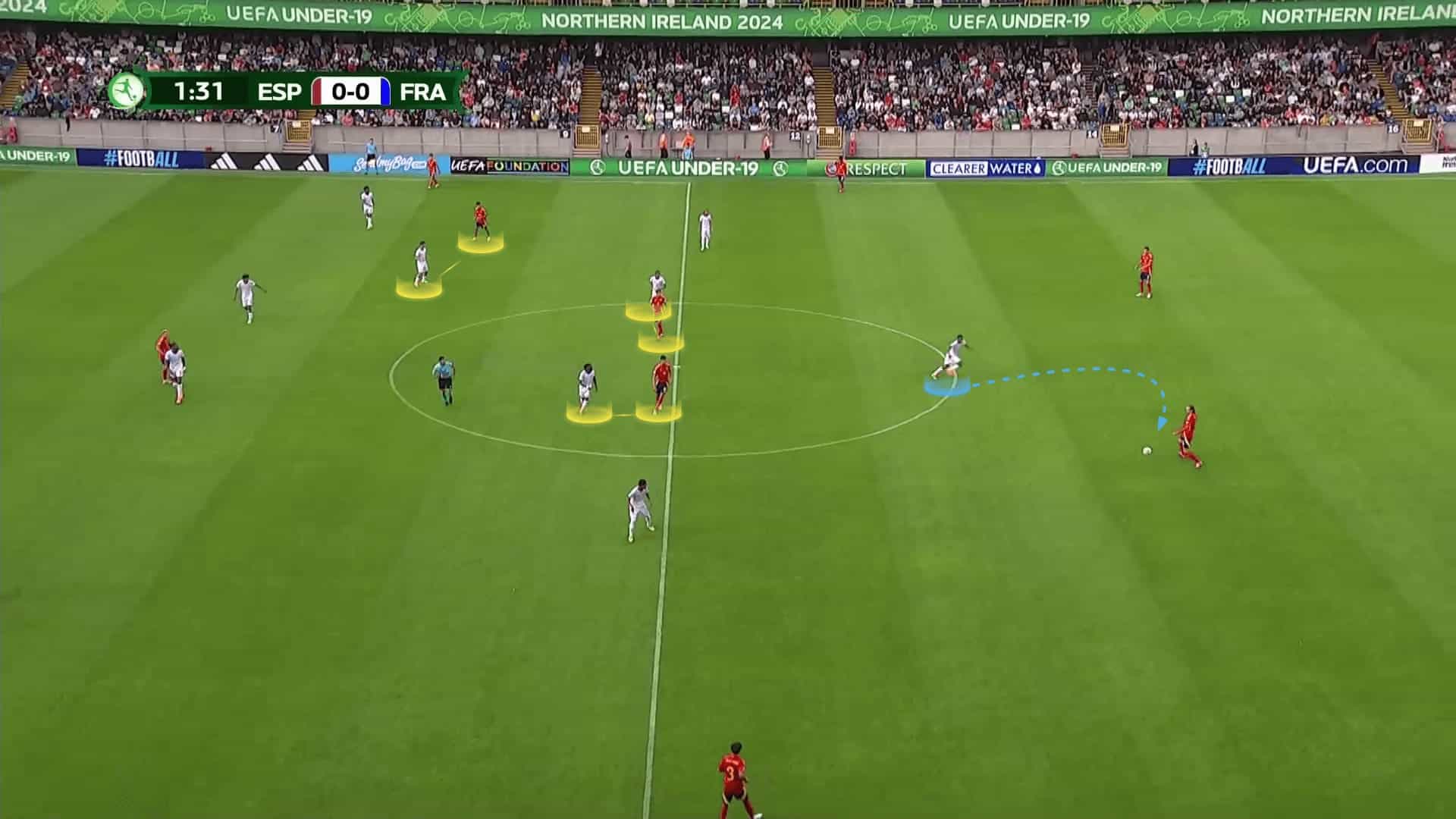

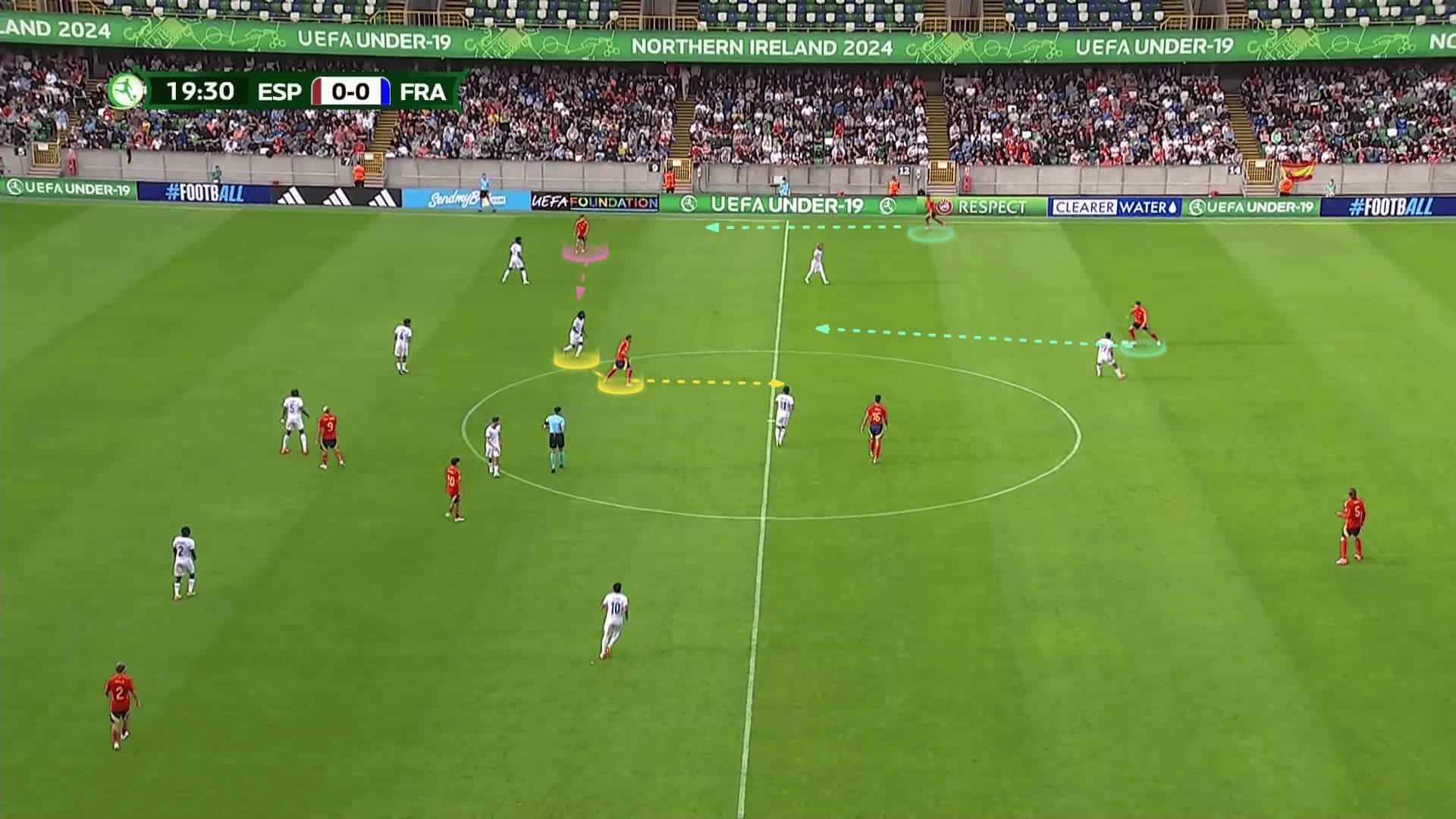

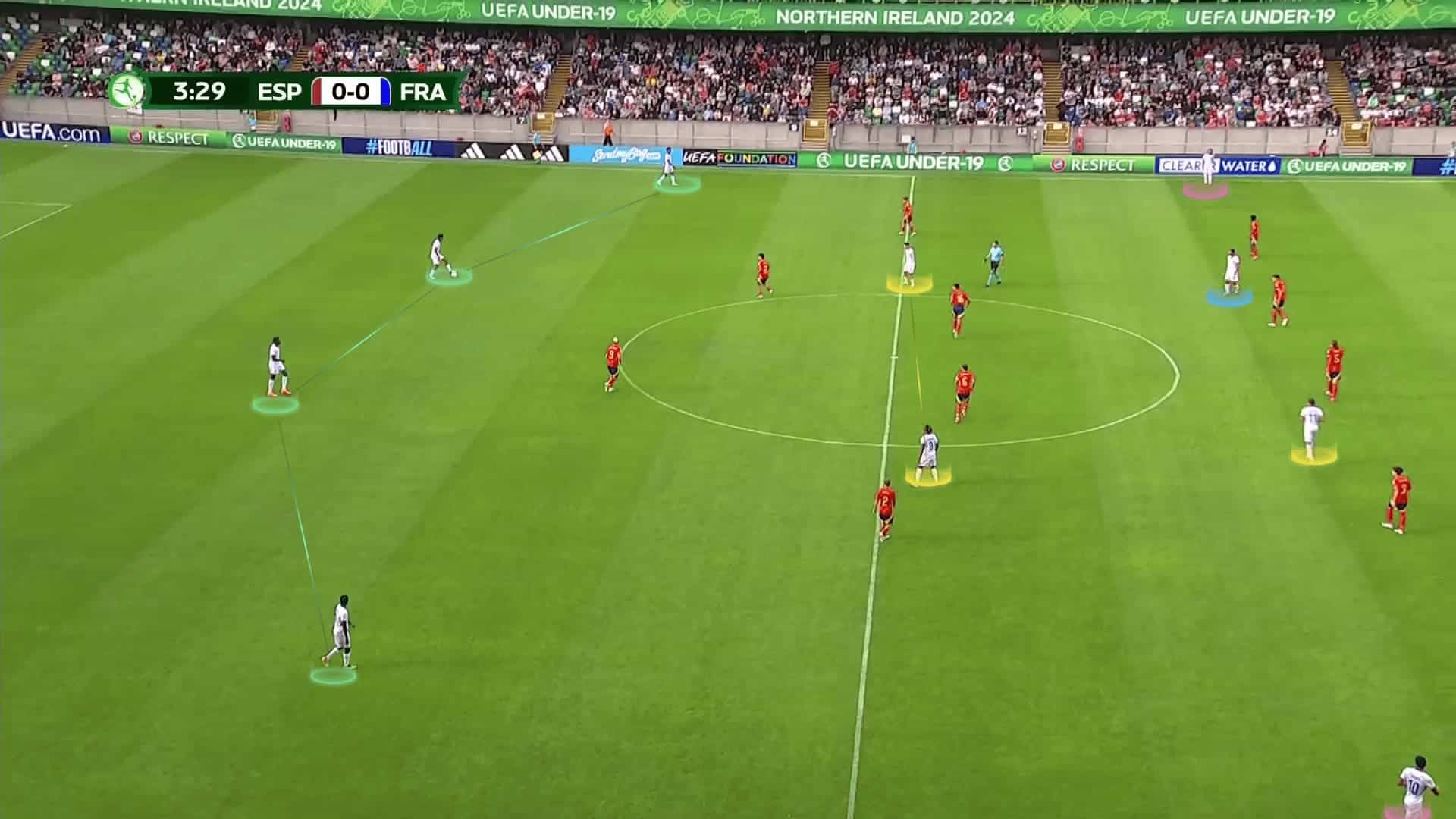

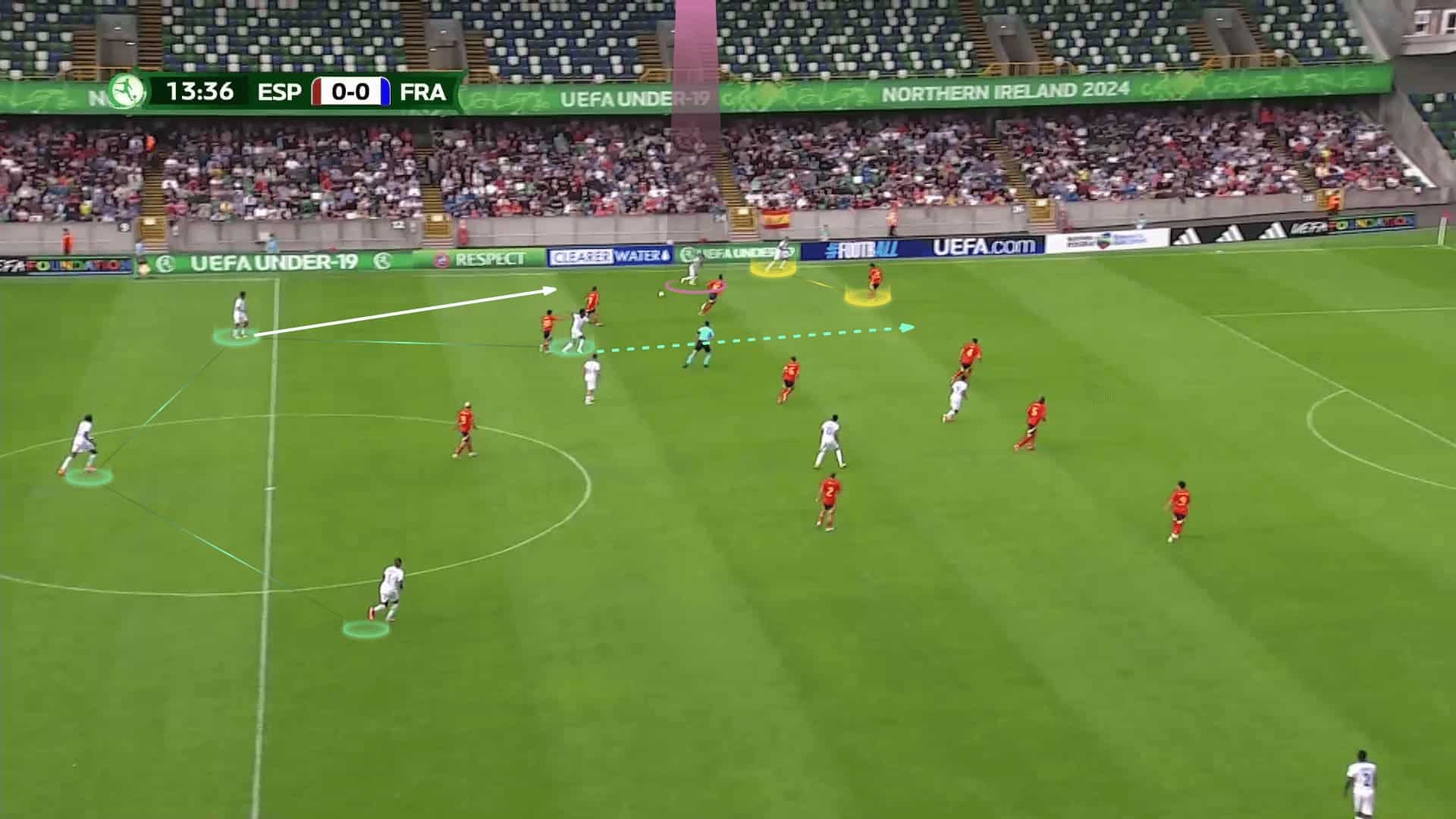

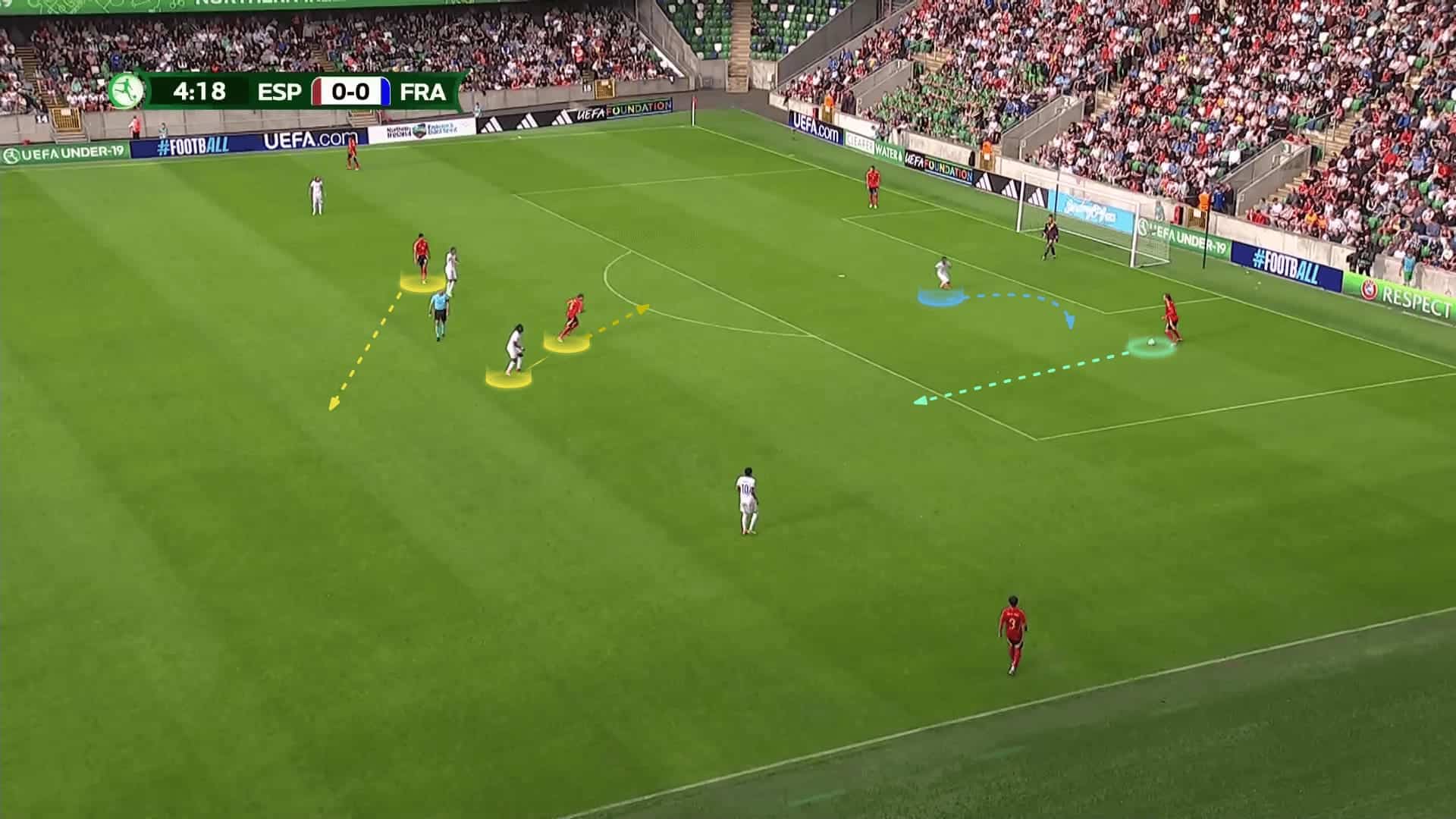

The photo below shows Spain’s 4-2-3-1 formation, with the two wingers stretching the width.

On the other hand, France’s scheme is 4-3-3, with three midfielders marking the three Spanish midfielders tracking them everywhere.

This means that only one striker should press two centre-backs, so he starts in a middle position and then runs in a curved way to press the ball holder, cutting the passing lane to the other to prevent shifting the ball to the other side, as shown below.

Ultimately, they want to force Spain to the flanks, where they can trap them, as shown below.

So, what were Spain’s ideas against this scheme?

The answer is simple: If you have good defenders with the ball, you don’t have to fear in these situations.

Spain depends on their defenders’ good dribbling abilities and composure on the ball, so the ball holder doesn’t stand waiting for the striker.

He will dribble with the ball, giving his teammates many solutions and asking the opponent some problematic questions.

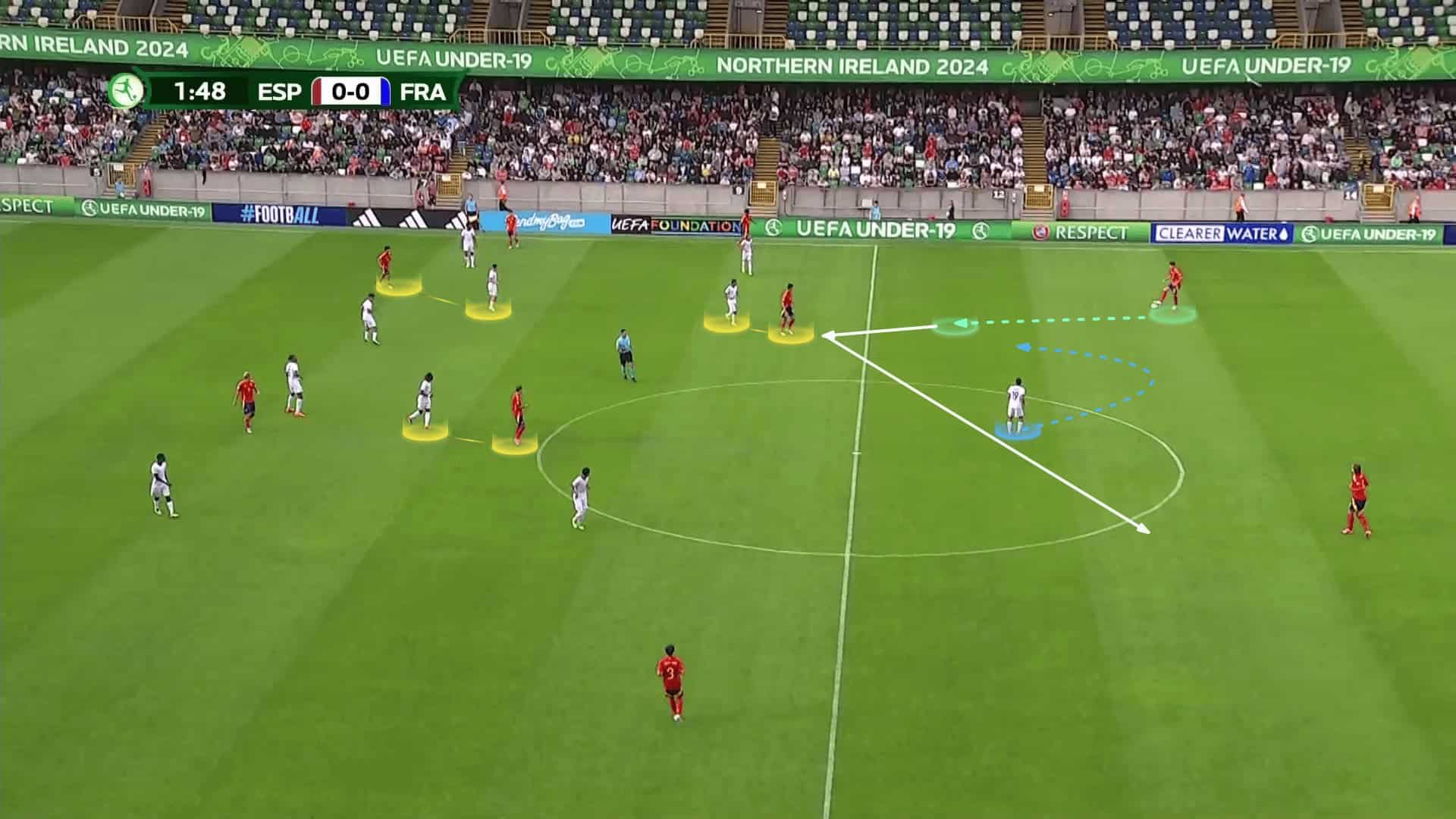

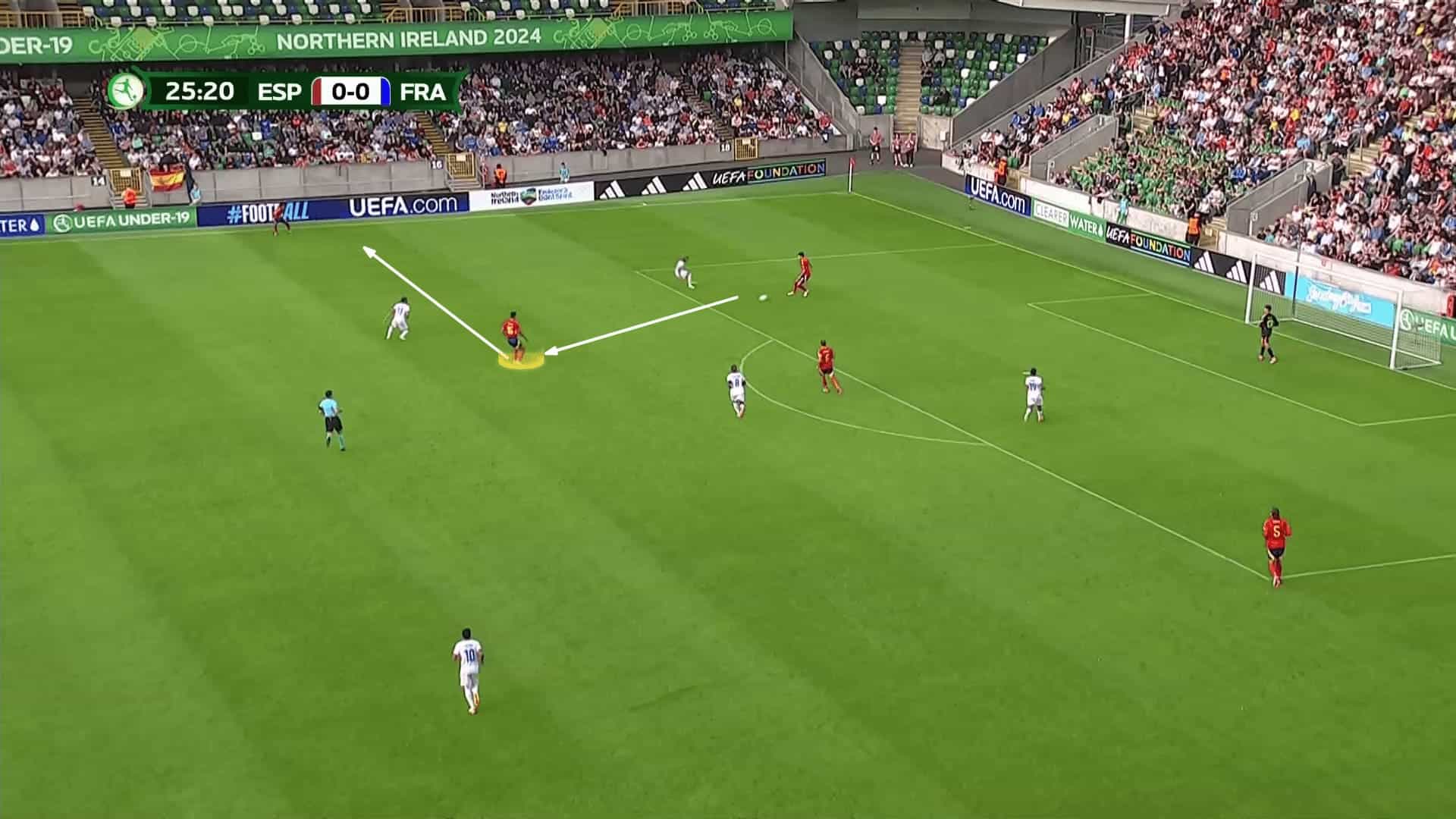

In the photo below, the right centre-back dribbles to drag the striker toward him and then uses a third-man pass to the other centre-back with the help of the right central midfielder.

Now, the striker is out of the game, so the other centre-back keeps dribbling to attract the French winger, who is forced to face him, leaving the left full-back, who becomes free.

That happens coinciding with two movements:

The left winger runs inside to drag the opponent’s full-back, and the Spanish striker drops to force the French right winger to close that passing lane to make sure that the left full-back is free.

In another case, you can see below that the situation is so static and closed, but with the defender’s dribbling and the striker’s drop, it becomes more open and dynamic.

The same striker and winger movements happen, which frees the left full-back, as in the two following photos.

Spain also tried to test France’s ability to defend against wing rotations, and the results were impressive for Spain, which was streamlined.

France couldn’t deal properly with this. Take your breath, and let’s go into detail!

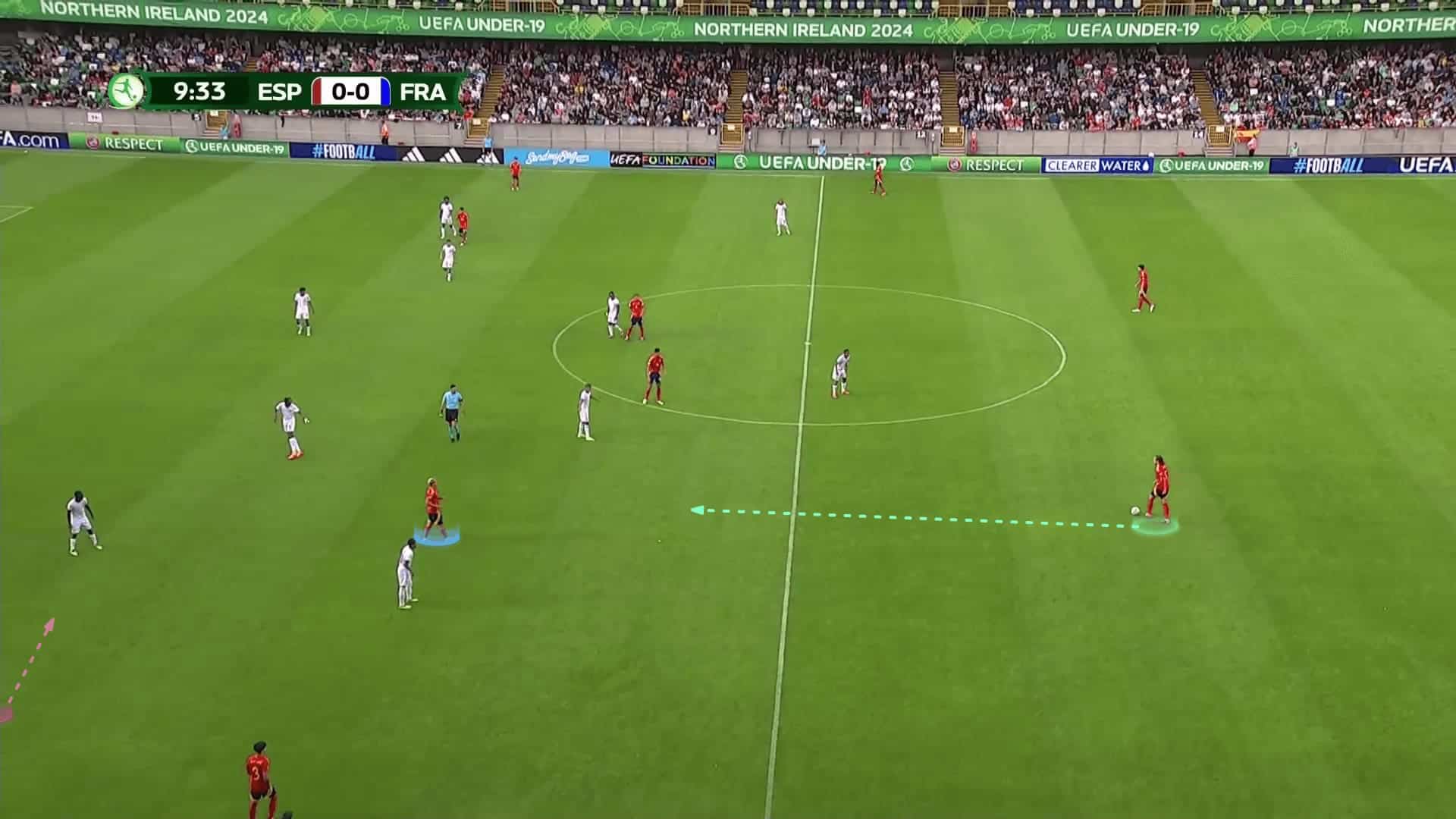

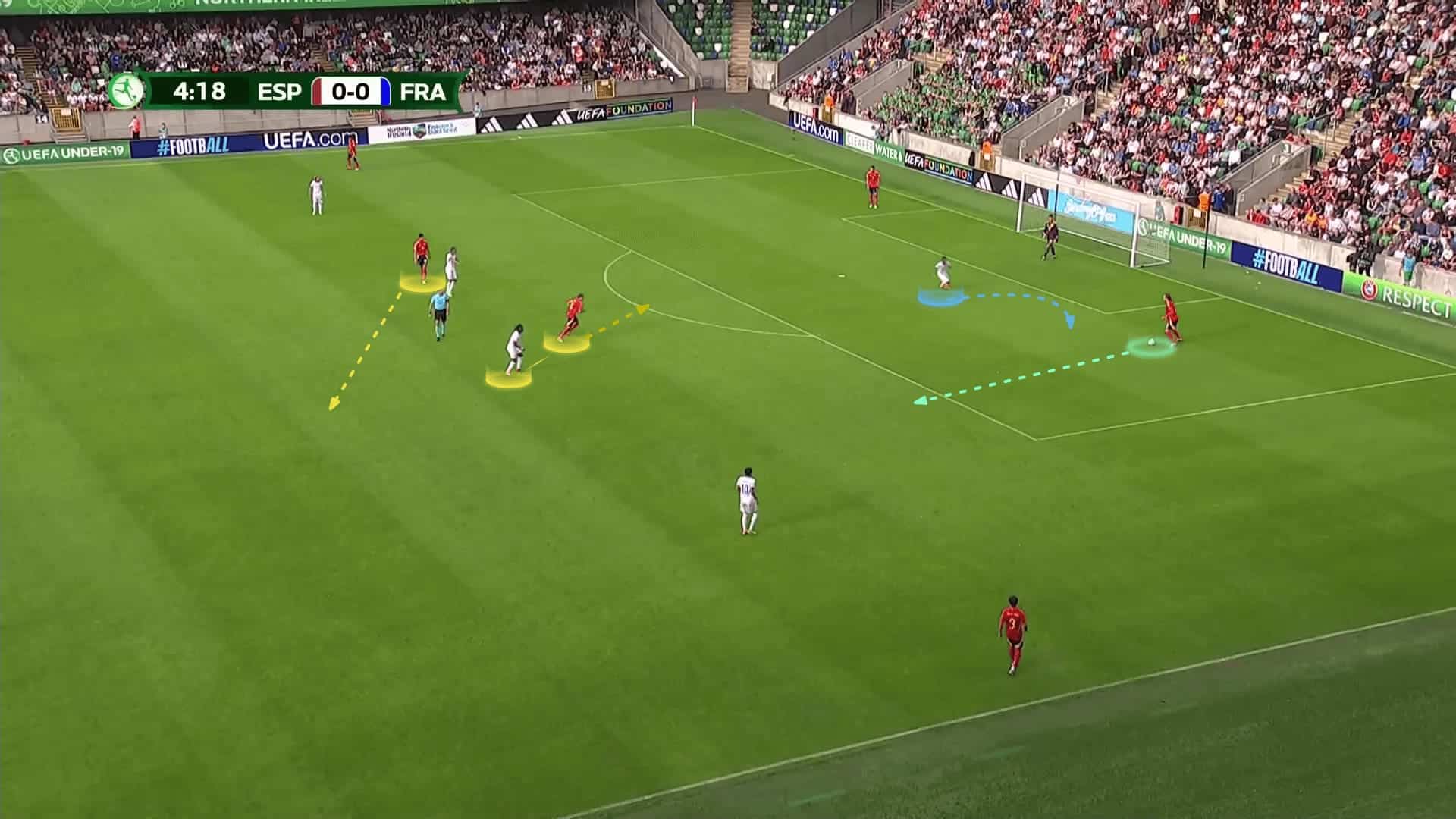

In the first photo below, the three-midfielder man pressing is straightforward, so the attacking midfielder, Rayane Belaid, who has the ball, doesn’t find it difficult to pass behind the French midfield to the right winger, who drops to receive in the half-space.

In contrast, the right full-back runs stretching the line, so France’s left full-back hesitates to follow the winger inside because he isn’t sure that his mate, the left winger, can drop all that distance.

The winger receives the ball and sends a through pass to the striker in a dangerous chance, as in the rest of the photos.

Here, the same principle is applied, with the usual amazing feints and dribbling from the centre-back, who gives time for the winger to cut inside and the right central midfielder to drag the French midfielder away from the passing lane.

The result is the same: the winger cuts inside, as shown below.

You may ask, what if the French left winger decides to stand narrower to close this passing lane? Let’s see.

In the first photo below, I want you to see how patient the centre-back is and how he dribbles until asking the opponent the inevitable question.

The French left winger decides to close the passing lane to the half-space, but the left full-back behind him also stands with the winger and isn’t ready to chase the Spanish right full-back early, so the flank is empty for the full-back, as in the second photo.

In the third photo, the left full-back has no options except going to the Spanish full-back, leaving the winger behind him, who passes the ball to the attacking midfielder who cuts inside the box, exploiting this sudden shift in France’s defence in a dangerous position inside the box.

As we have mentioned, France’s first choice wasn’t the high pressing, but they pressed highly against Spain’s build-up from GKs, especially in the second equaliser, to score the equaliser.

France followed the same strategy by asking the striker to do that run and with the three midfielders in the same man-marking as the Spanish ones. Spain decided to manipulate these markers to create space.

In the photo below, the attacking midfielder stands as a forward, out of the box to drag a midfielder with him.

In contrast, the midfielder near the ball drops to drag his marker out of the game to empty a large area in the middle for the far midfielder, who cuts suddenly toward the ball.

Now, you can be not surprised when you are told that the left centre-back dribbles with the ball, winning enough time and space for this process.

The plan works, as shown below.

In a similar strategy, the two central midfielders drag their marker to empty the path of dribbling for the centre-back, who reaches high areas, finding no obstacles until the striker uses the pin-and-roll run to drag the centre-back out of position and then receives a long ball behind him, as in the second and third photos.

But the goalkeeper deals excellently with it going forward while the other centre-back goes to cover, as in the fourth photo.

In another build-up idea, the centre-back passes the ball to the other centre-back after the usual dribbling.

This triggers the far winger to press the other centre-back, leaving the full-back, who will receive a brilliant third-man pass, as shown in the second photo below.

After that, they asked the winger not to go to press, instead organising themselves in a mid-press until they conceded a goal and needed to press more aggressively, so they asked the winger to press the far centre-back from the beginning, as shown below.

But Spain brilliantly broke this scheme many times by using a direct, long, and accurate pass from the centre-back, after dribbling, to the far full-back, as shown below.

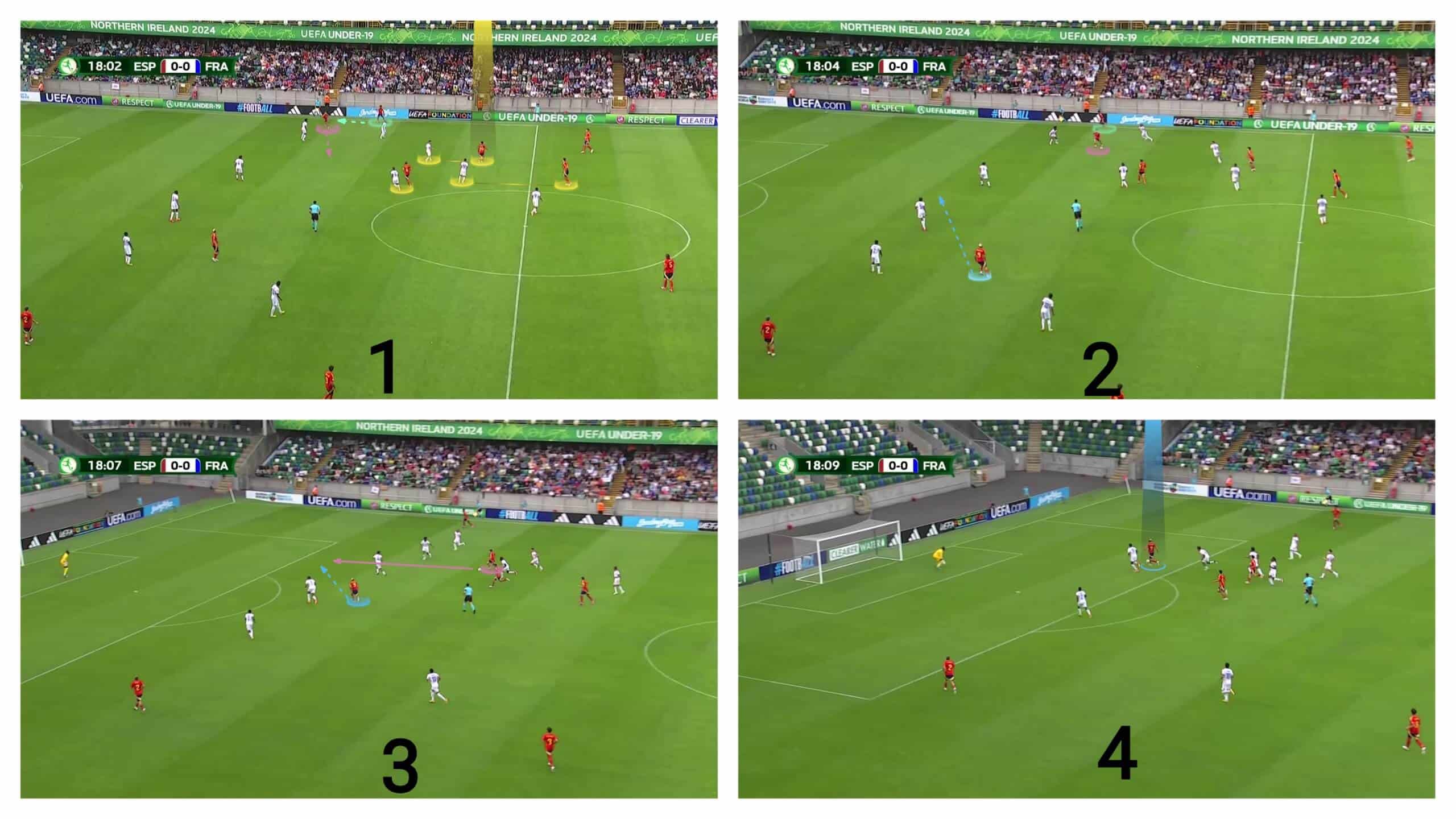

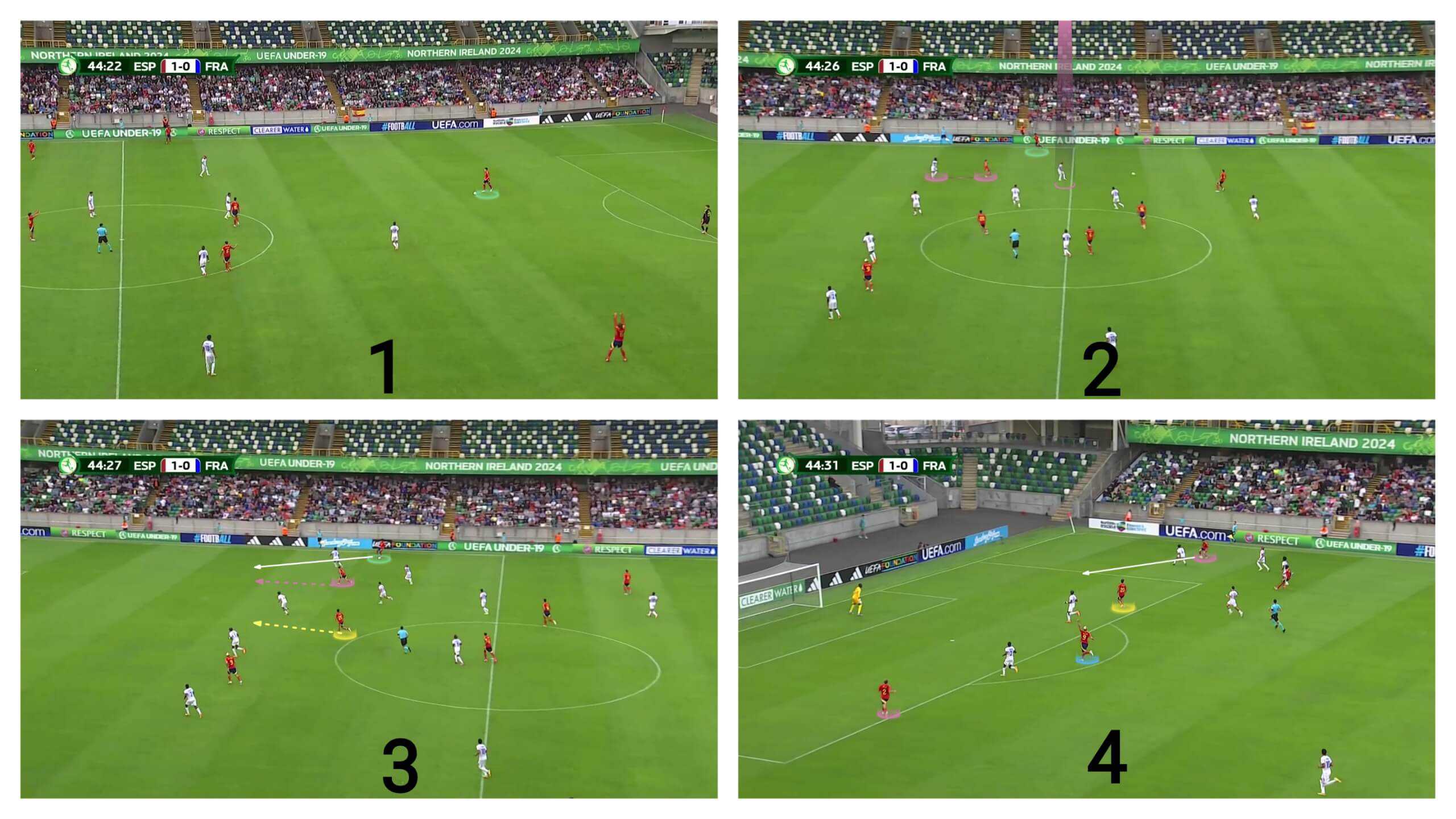

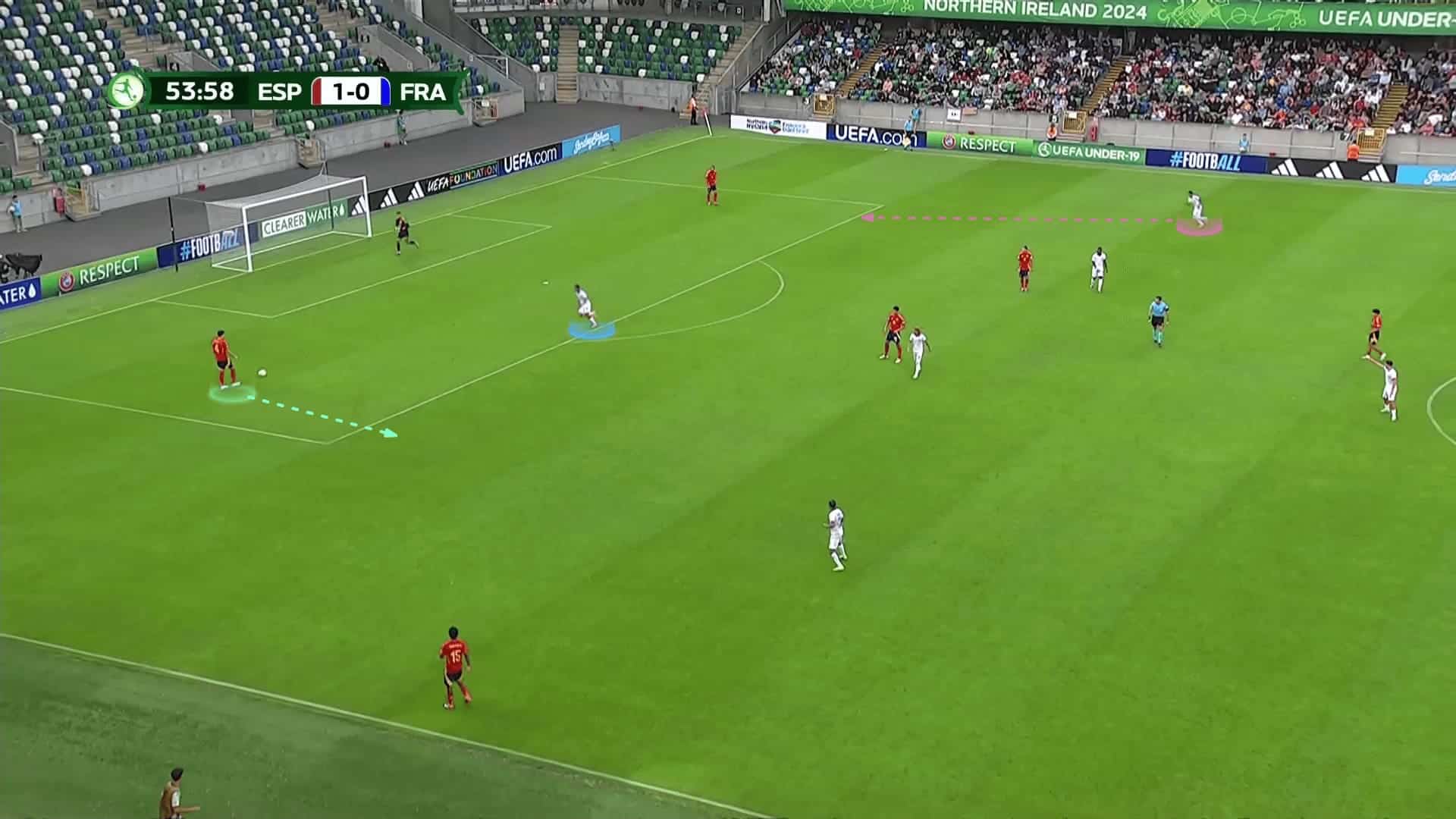

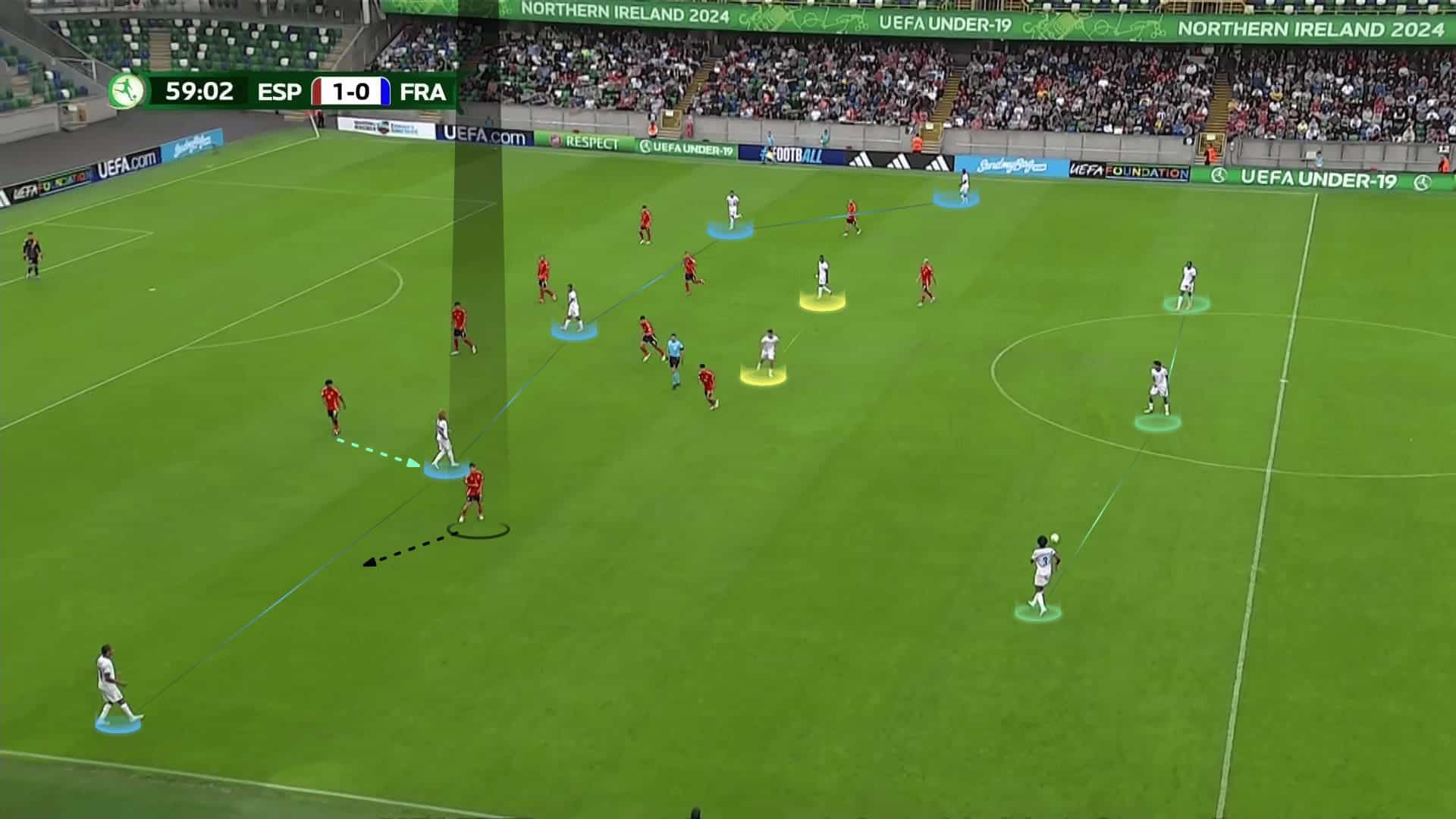

After that, France needed to change the pressing scheme to get the ball back quickly, so they started with two strikers pressing the two centre-backs while three players in yellow behind him were ready to press three of Spain’s players: the two full-backs and two midfielders.

In contrast, the attacking midfielder stood more forward, with the French holding midfielder. These three shifts toward the ball, leaving the far full-back free.

In the first photo below, Spain’s solution is to ask the right midfielder to drop standing as a full-back.

In contrast, the full-back pushes forward, which puts the opponent’s left full-back in a difficult question: being with the full-back inside or the winger on the line, out of shot, as in the second photo below.

Due to this 2-v-1 situation, the winger receives the ball, passes it back to the full-back and runs to receive the through pass leading to the second goal, as in the third and fourth photos.

France In Possession Vs Spain Out Of Possession

Spain didn’t press heavily, so they were in a mid or low block most of the match.

France spent most of its time in progression and the final third.

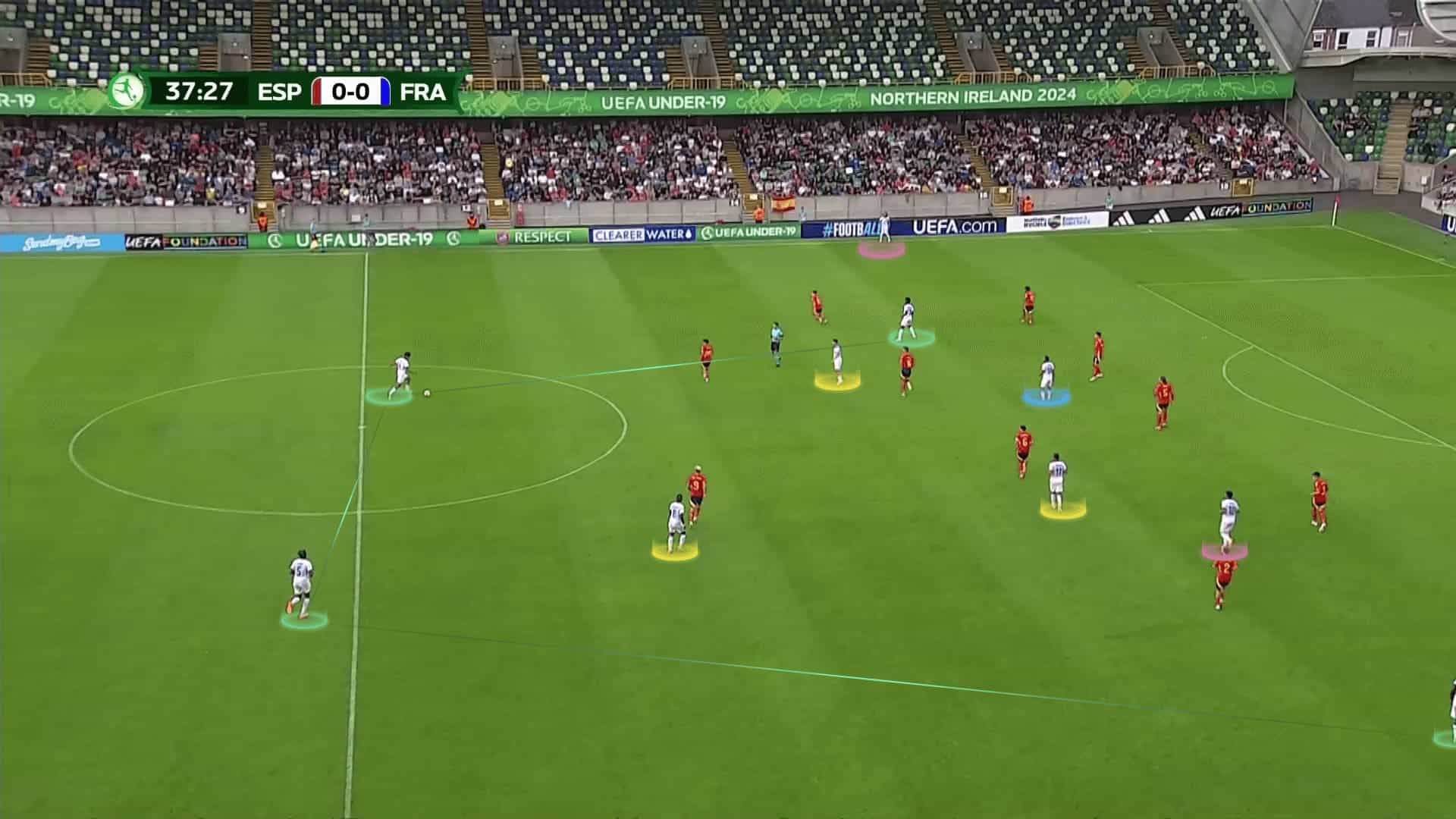

In progression, France was in a 4-2-3-1 shape, with the attacking midfielder having the freedom to join the striker, as in this case, help in wing rotations or receive between the lines.

This was against Spain’s narrow 4-4-2, as shown below.

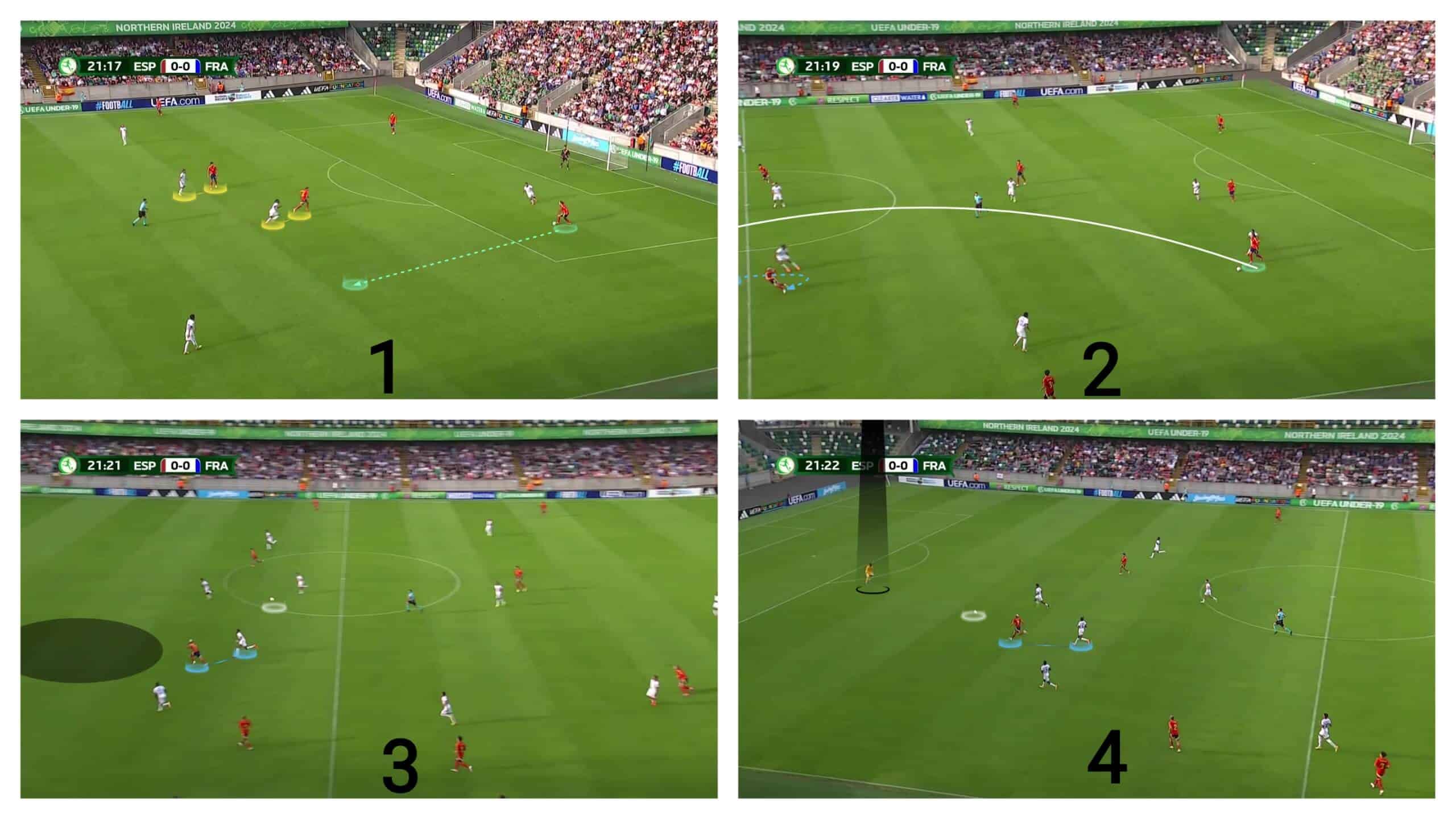

France’s main idea is to deliver the ball to Saïmon Bouabré, the left winger, in a 1-v-1 situation.

So, the first way is to ask the left full-back to dribble inside, dragging Spain’s right winger to open the passing lane to the targeted left winger by passing the ball back to the centre-back, who passes the ball to the left winger, as shown in the two photos below.

They also sometimes exploit the free attacking midfielder in this process, so he stretches the width to attract the full-back, giving the targeted left winger the space he needs to receive this direct pass from the left centre-back, as shown below.

It’s also remarkable that the left full-back cuts inside the space created in the half-space.

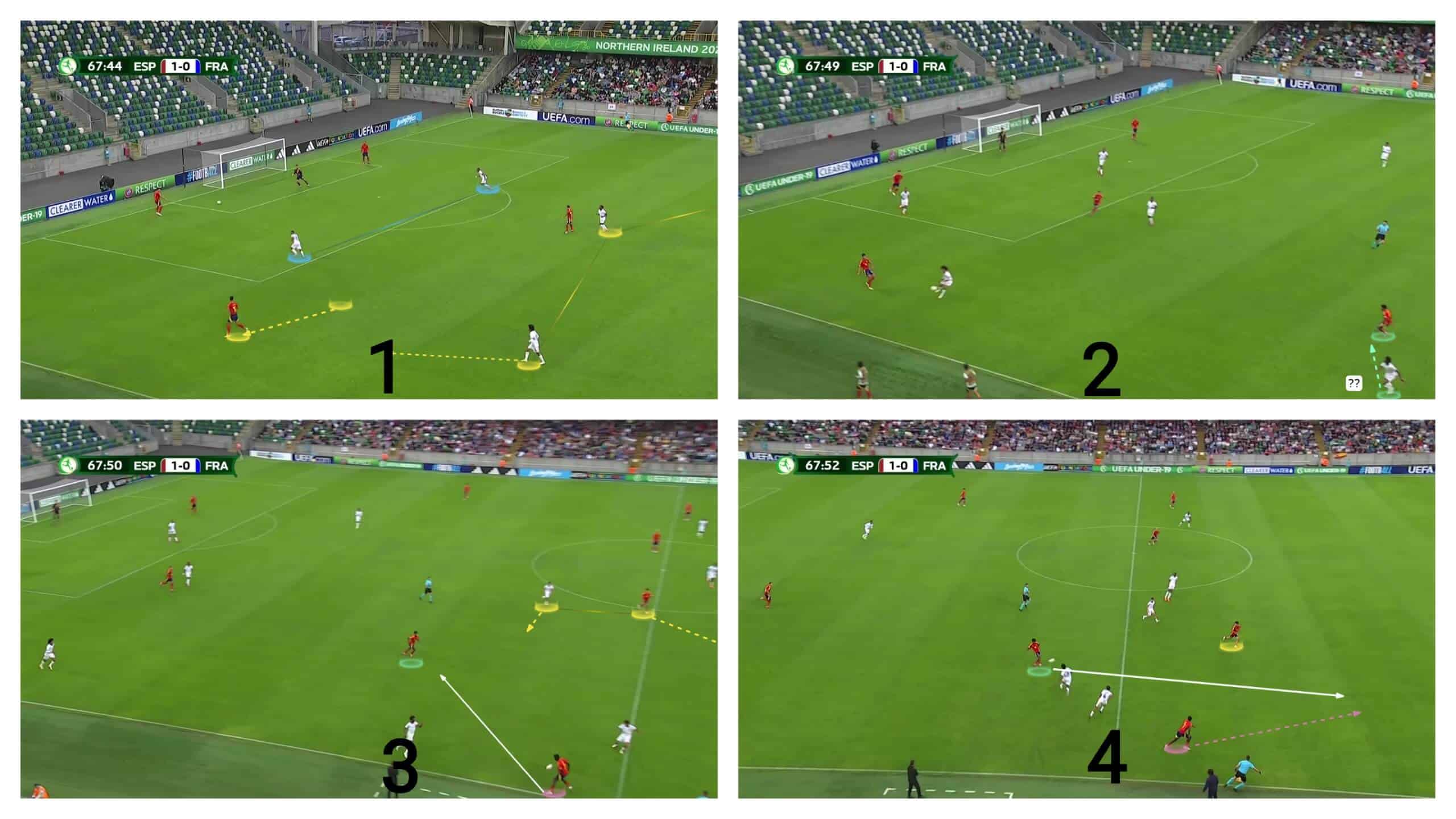

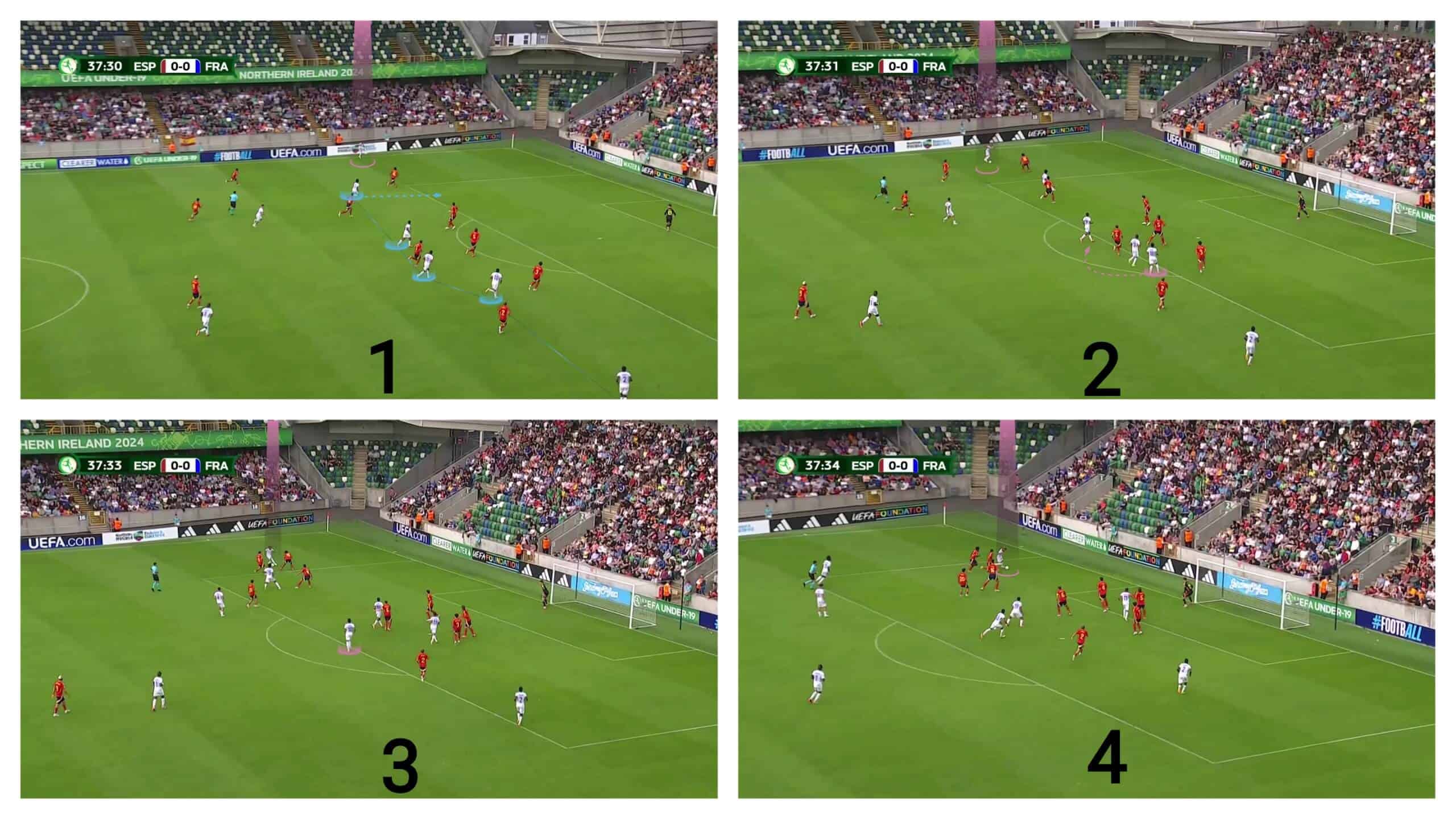

When they push more forward, reaching the final third and box-attacking after that, they sometimes push most of the players forward, like in a 2-2-6 formation with the left winger and the right full-back stretching the width, the left back and the right winger in half-spaces, and the striker and the attacking midfielder in the middle, as shown below.

This gives them the chance to create a 1-v-1 situation, exploiting the talented left winger while being destructive in box attacking and having many options, as in the first photo below.

They also ask the far winger to cut behind the defence to receive a cut-back pass or rebound, as in the second and third photos.

In the end, as in the fourth photo, he could pass the two opponents.

In the second half, they followed the 3-2-5 shape, asking the left winger and the attacking midfielder to change their roles, so the left winger became the one on the half-space to take the attention of the full-back, dragging him to open the space on the flank to the attacking midfielder, who became the winger now, but Spain was ready with their 4-4-2 narrow scheme asking the full-back to fill the half-space while the winger has the role to keep tracking on the flank, even if they reach to be six players in the back, with the two wingers drop widely, as in the two photos below.

Conclusion

In this analysis, we have shown how each team dealt with different phases of play, whether in-possession or out-of-possession phases, showing the strengths and weaknesses in each phase.

In addition, we have explained in detail how Spain’s centre-backs were a critical factor in the battle, showing great abilities and composure with the ball.

Comments