Apart from the UEFA Champions League big clash between PSG and Real Madrid, in Spain, there was another team hosting a European game. Since Sevilla were also playing West Ham United in the same UEFA Europa League round, the game of Real Betis and Eintracht Frankfurt was moved a day earlier to facilitate better crowd control.

This was also an interesting game because both teams are doing fine in their leagues. Under Manuel Pellegrini, Betis have grown into a team that could challenge the top four, but the Chilean head coach’s immediate task was to take on Oliver Glasner’s side, a team that was influenced by the Red Bull philosophy. It was a rare opportunity because Pellegrini seldom faced this type of manager from Bundesliga, and in this game the guests were the better side with superior tactics. This tactical analysis will explain the roles of Glasner’s half-wingers/10s in this game, which became the key to securing an important Frankfurt victory away from home.

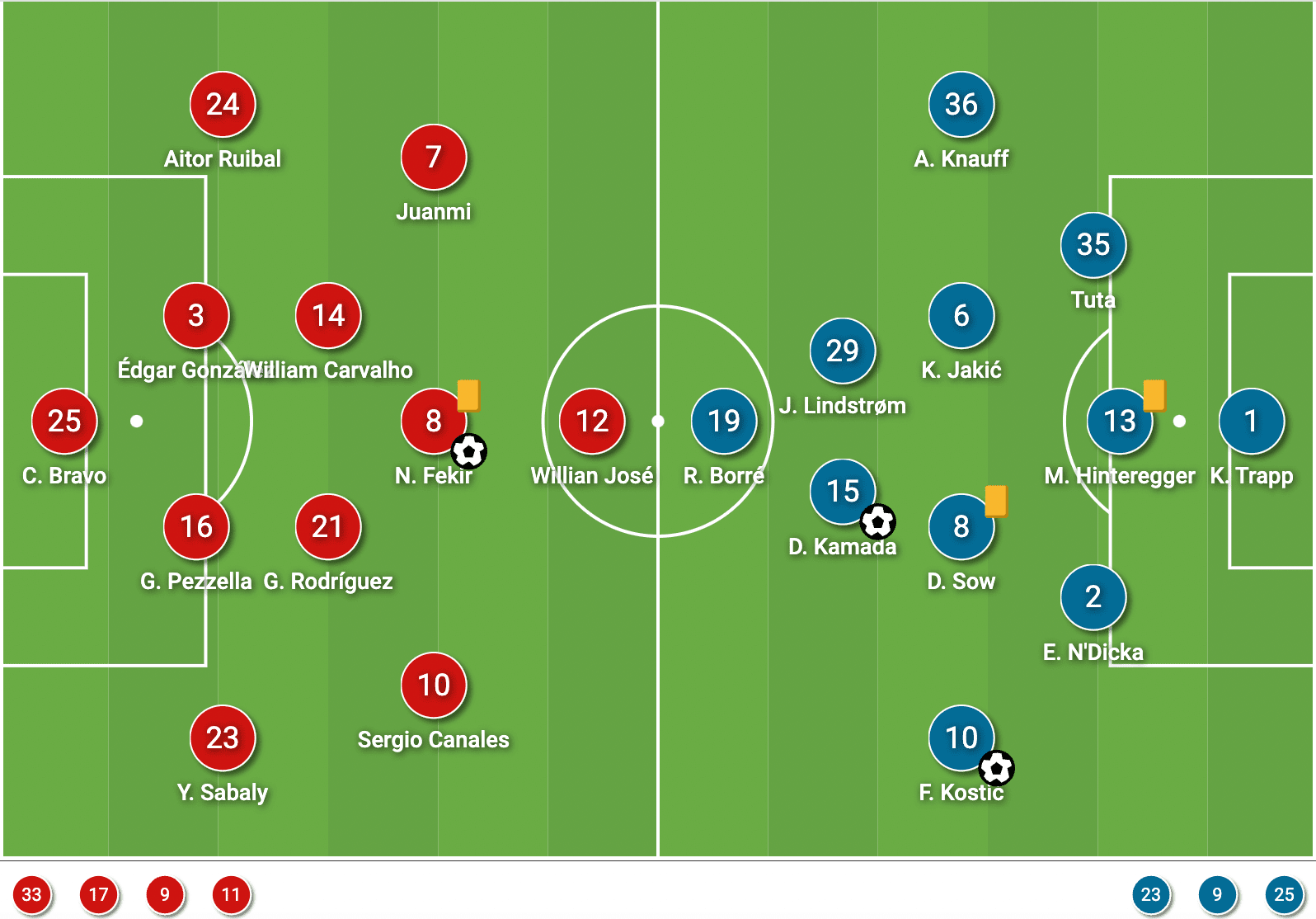

Lineups

Pellegrini treated this competition very seriously as their best group of players all started, including the lively attackers, Nabil Fekir, Sergio Canales, and Juanmi. In the midfield, William Carvalho paried up with Guido Rodríguez. In the defence, the back four was formed by Aitor Ruibal, Edgar González, Germán Pezzella, and Youssouf Sabaly.

Frankfurt were better in this 3-4-2-1 formation than the 3-4-1-2, because the duo, Daichi Kamada and Jesper Lindstrøm fit in better as the 10s, supporting Rafael Borré. Borussia Dortmund loanee Ansgar Knauff started as the right wing-back. Filip Kostić as the left wing-back. The 6s were Djibril Sow and Kristijan Jakić. The back three included Tuta, Evan N’Dicka, and Martin Hinteregger.

10s in the half-spaces

In Frankfurt’s system, there are two players behind the strikers, who have hybrid roles with and without possession. Whatever how you called them, half-wingers, 10s, or attacking midfielders, in this analysis, we are going to explain how these players contribute to the side tactically.

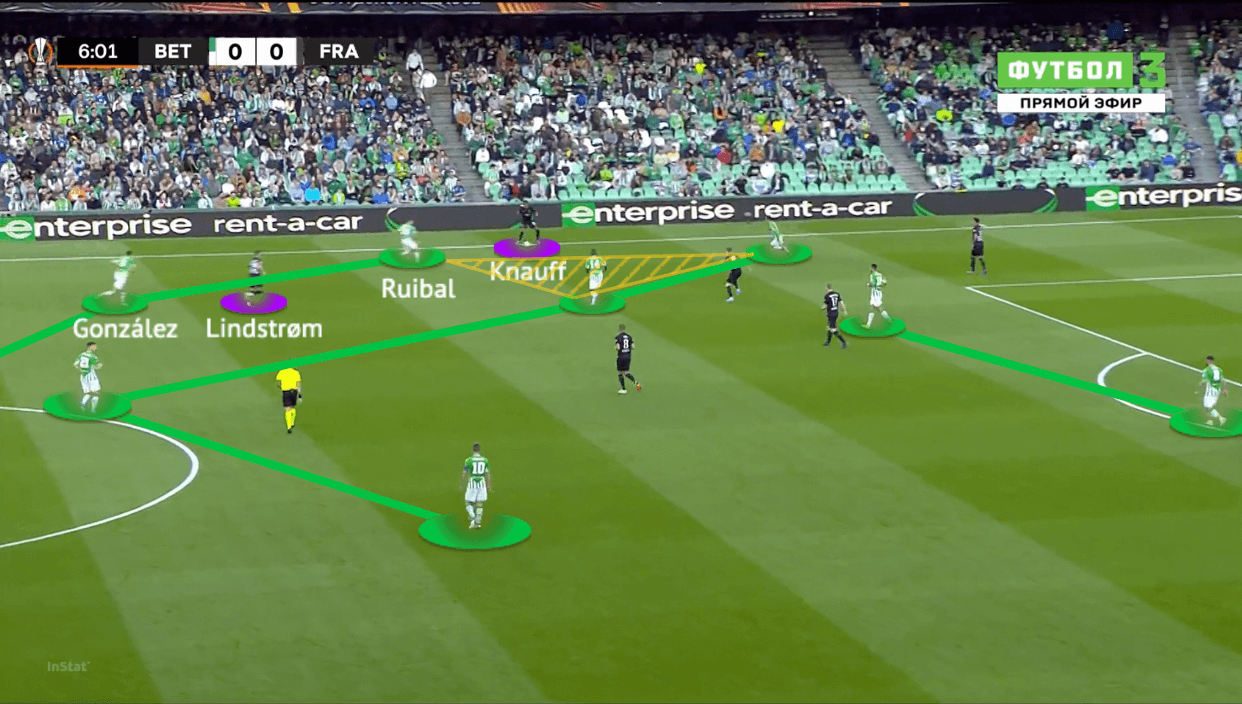

Without possession, Betis committed themselves in more a 4-4-2 shape with Fekir joining José in the first line. When they pressed, ideally, they could use the full-backs to close wide spaces as Ruibal approached Knauff on the above occasion. Then, when the Frankfurt 10 drops, the centre-backs should be tightly marking and closing him down so the opponents could not proceed anyway.

But in this game, Frankfurt’s 10s were great positionally, they sneaked in the half-spaces very well to create chaos on the defence, posing questions to imbalance the Betis formation.

Mainly because the Frankfurt 10s were in the half-spaces, Betis were without a clear and specific solution to deal with these players. It was a 4v2 in the midfield, and Betis were unable to close the central spaces since having both 10 and 6 gave Frankfurt a more staggered structure in the constructions.

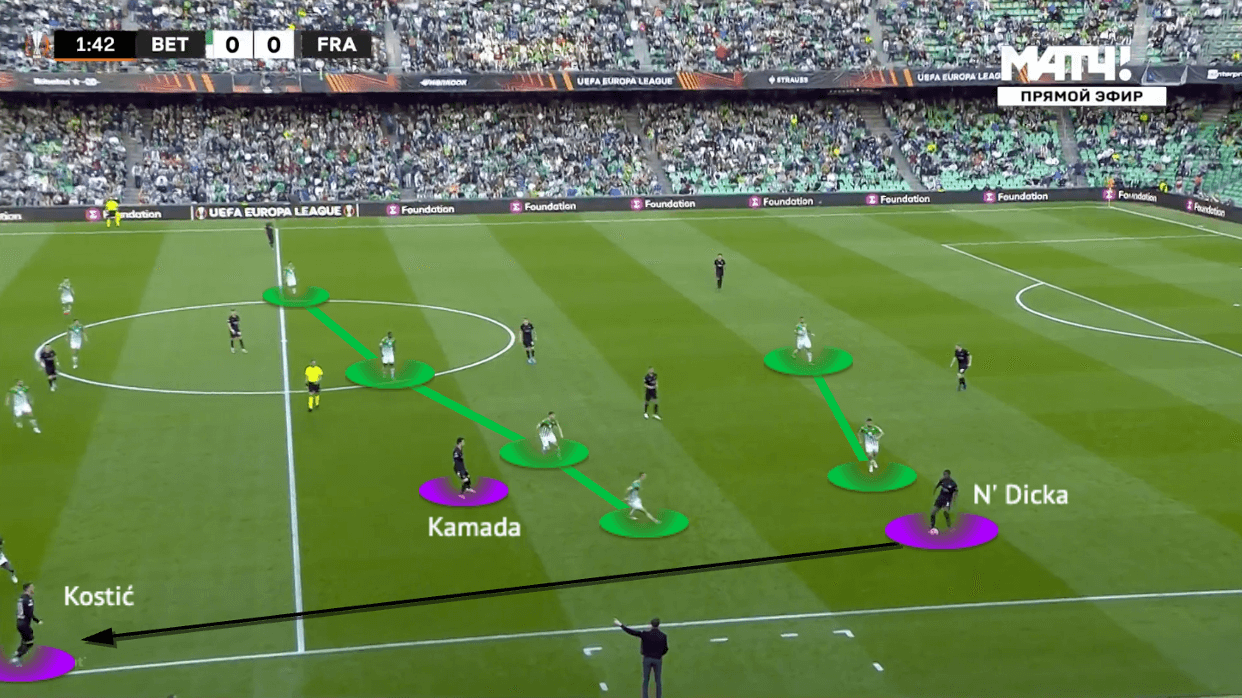

In the first line, Betis only had two players, while Frankfurt had three, it was obvious that the third centre-backs could always be the free player to pass. In this game, the wide centre-backs, Tuta and N’Dicka were progressing plays mostly, as we have shown in the above image.

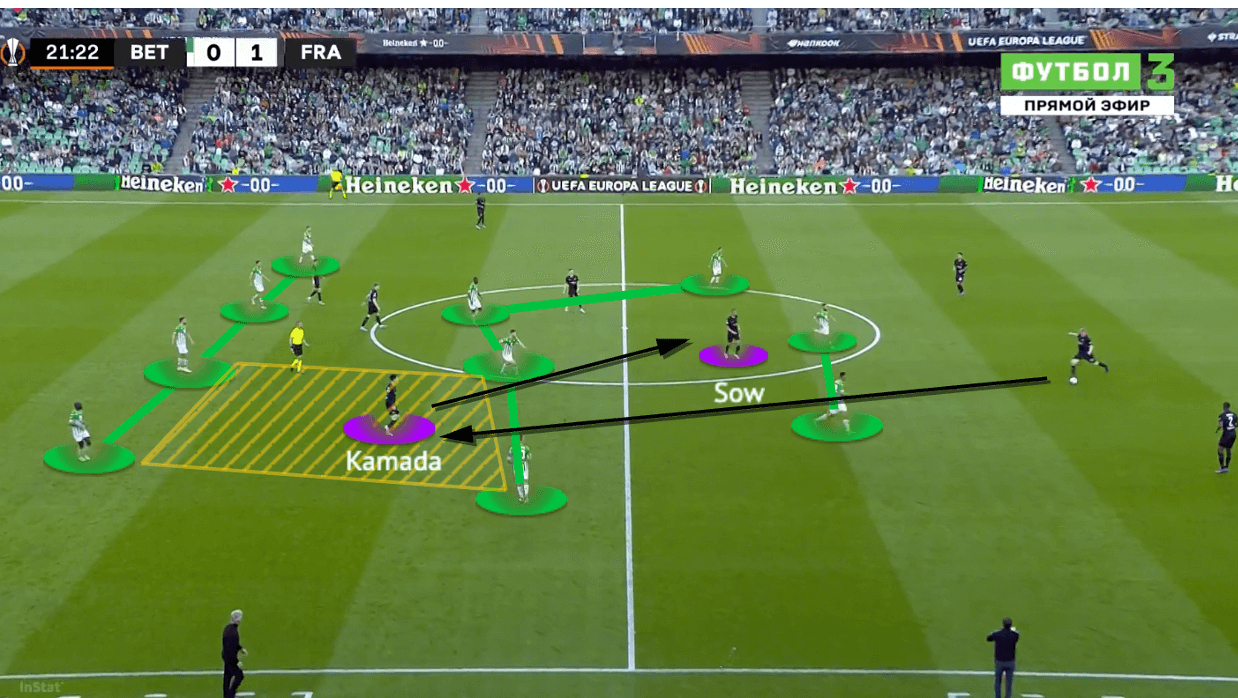

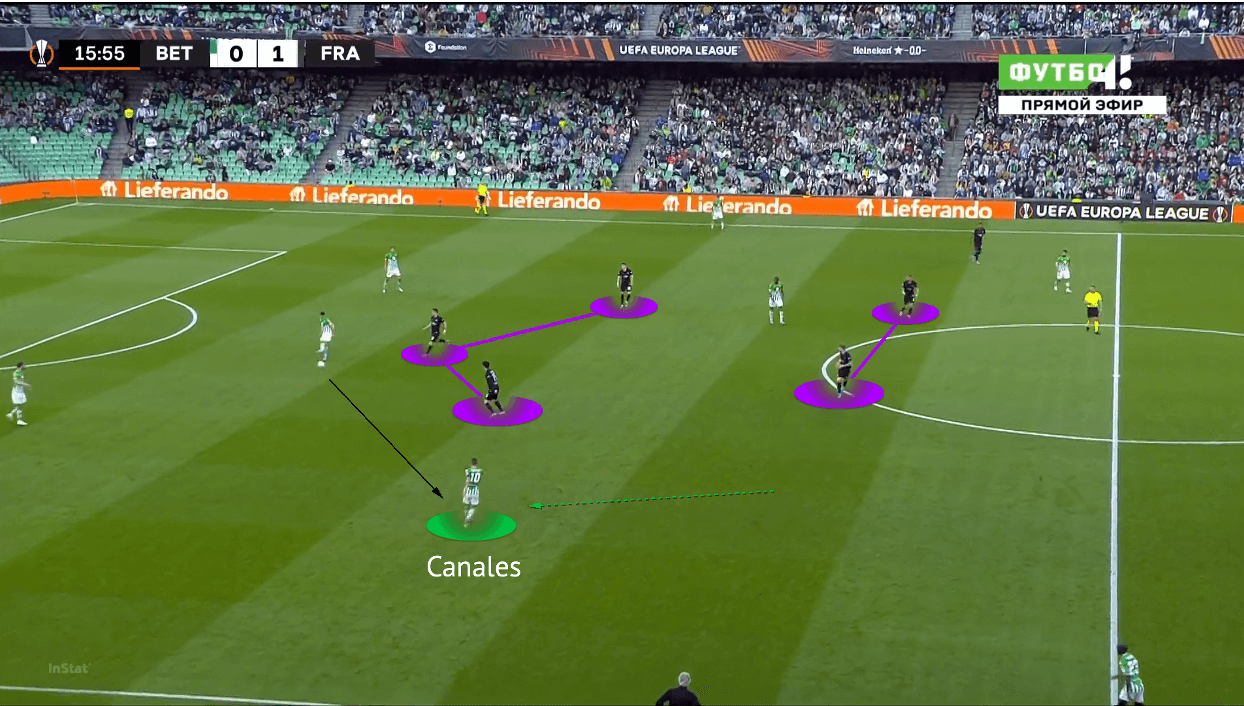

In the midfield, as Kamada dropped very deep to the half-spaces behind the second line, his presence attracted the attention of the Betis midfielder and winger. While both Betis players were trying to cover him in the half-spaces, their defensive actions were limited – Canales could not press N’Dicka or cover the passing lane to Kostić out wide.

With the 10 moving deep to help the construction, Frankfurt usually had four players close to support each other on the outside, including a wing-back, a centre-back, a 6, and a 10. That was useful for generating passing options to move the ball around.

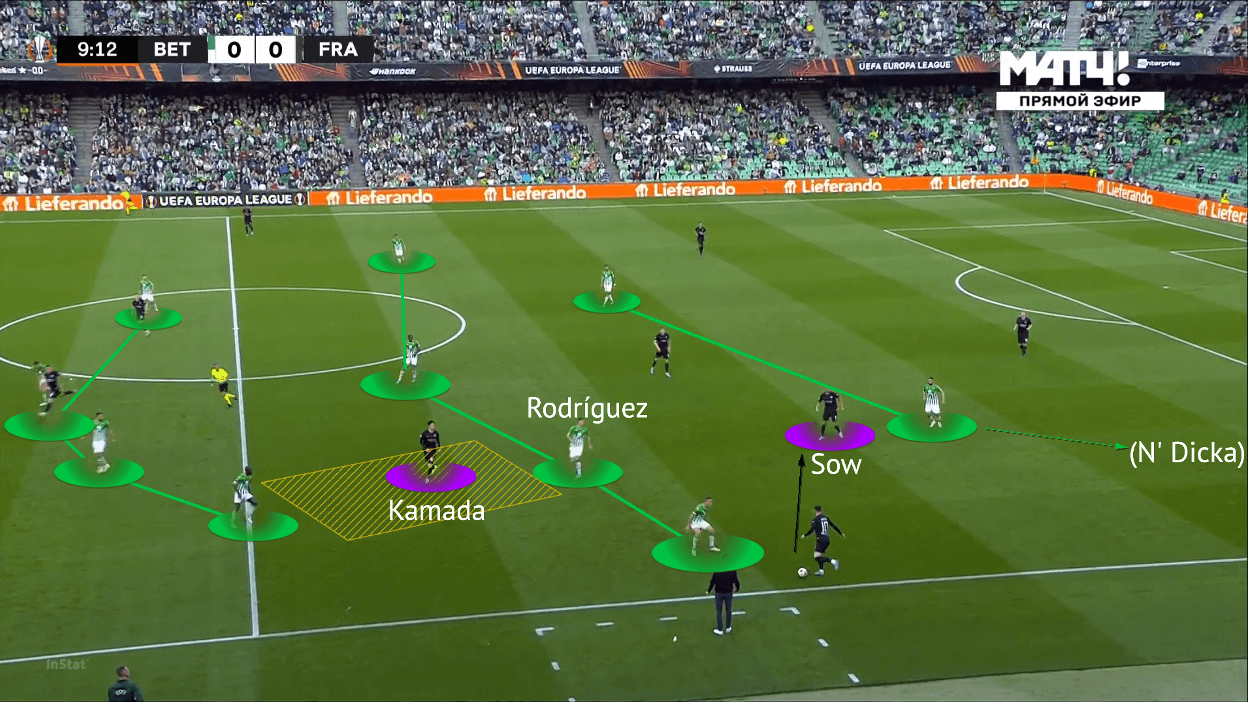

The above image reflects another scene of Kamada’s involvement without touching the ball. He stayed in the yellow zone to occupy both Sabaly and Rodríguez simultaneously, as a result, Betis could not close Sow in the centre because their midfielder was dragged away by the Frankfurt 10. With N’Dicka, the centre-back, to offer enough depth in the first third, that also dragged away the striker to create enough spaces in the centre for Frankfurt to attack. That’s why Kostić could use Sow as a solution to transport the ball to the weaker side of the defence.

With the roaming 10, apart from circulating possession in their own half, Frankfurt could also achieve progression via the third man. In the above image, Kamada once again moves into the yellow zone to connect, and the defenders were not following. Sow was deployed as the third man in this attack for further progression. Even though the Frankfurt 6 was not facing the opposition goal in the initial pass, his body angle was adjusted very quickly, and we believed this could be one of the practised moves in training sessions.

So far, we have shown examples including Kamada only, because the Japanese player was really good in spaces. Although Lindstrøm on the other side also served similar functions and did it finely, he was more of an attacker in the final third who posed threat to the opposition goal, with better 1v1 and individual skills.

The last example of the section shows the 10 on the other side, when he stayed in the half-space, this time, the decision of Betis full-back was to follow. Consequently, Ruibal was caught out of position and too high, which Knauff exploited that space by a run in behind and Tuta released the wing-back with a long ball.

In this section, we explained different impacts attributed to Frankfurt 10’s tricky positionings, and how these positions opened passing options and spaces for the constructions and Pellegrini’s side had not come with a clear solution to handle it.

10s’ roles in the press

Without possession, the Frankfurt 10 were not 10 anymore, they might be seen as wingers in a 3-4-3, or even strikers in a 3-4-1-2. In the defence of Glasner’s side, the numbers are the less important because the pressing is driven by his principle of plays. With a zonal-man oriented system, that defensive shape could vary.

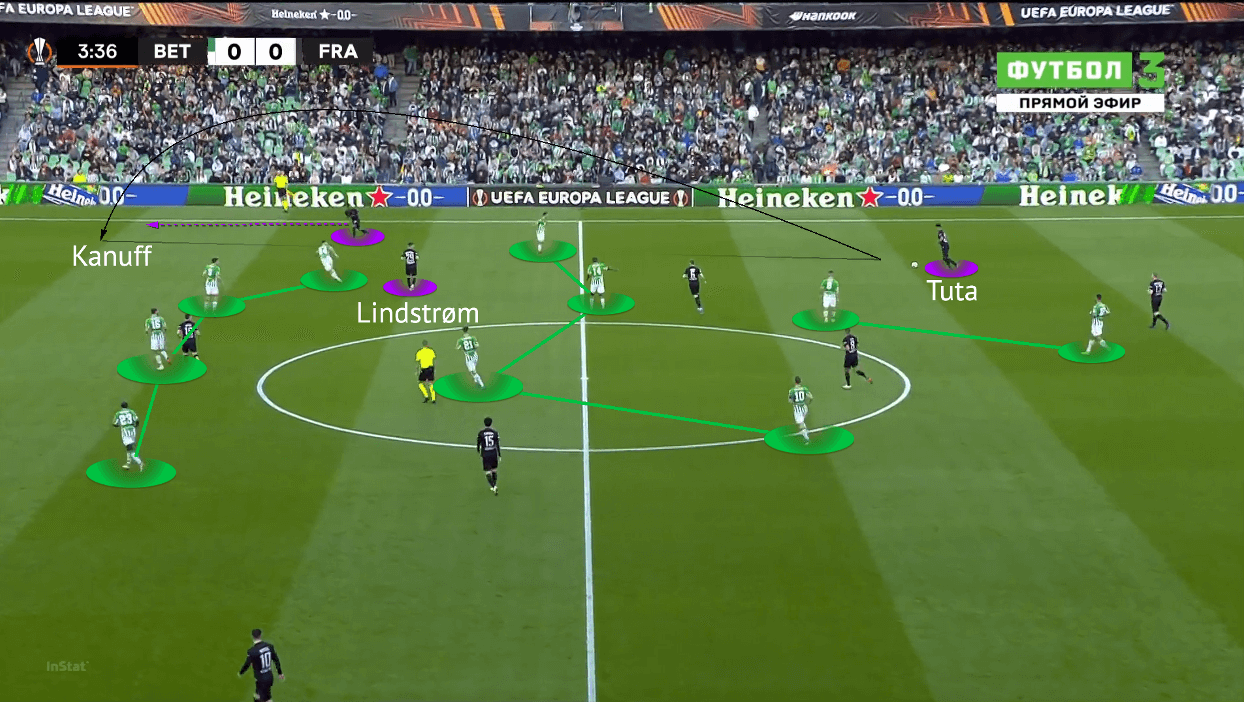

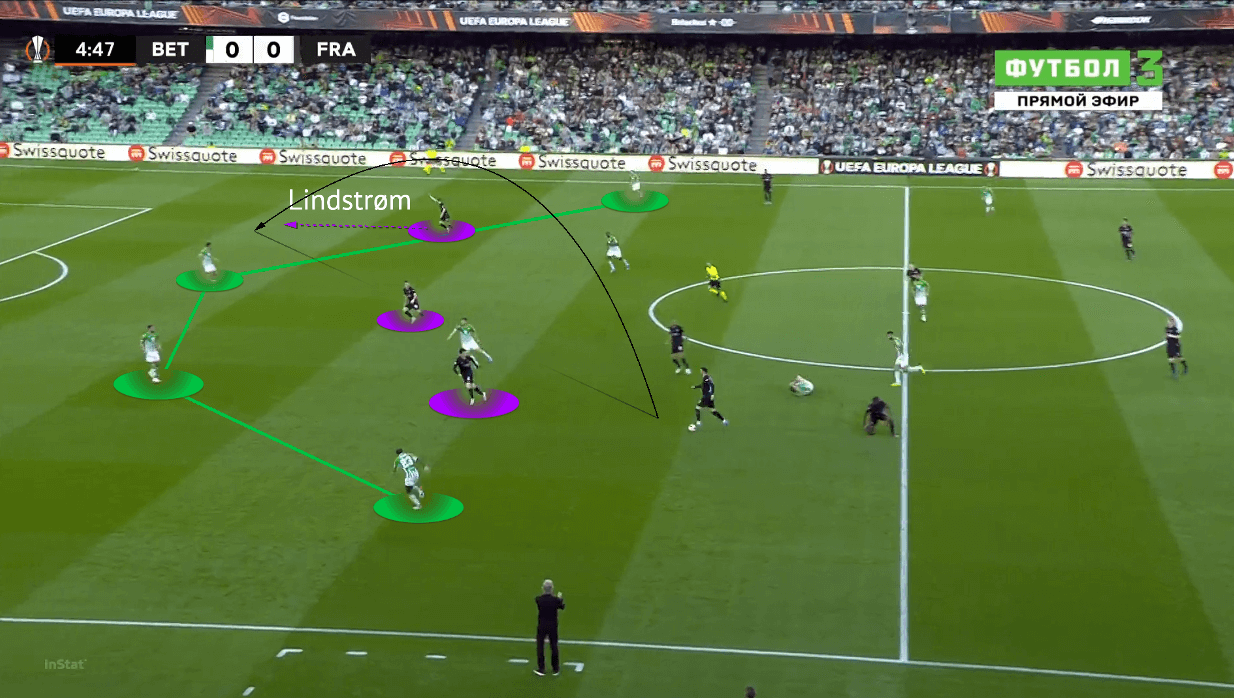

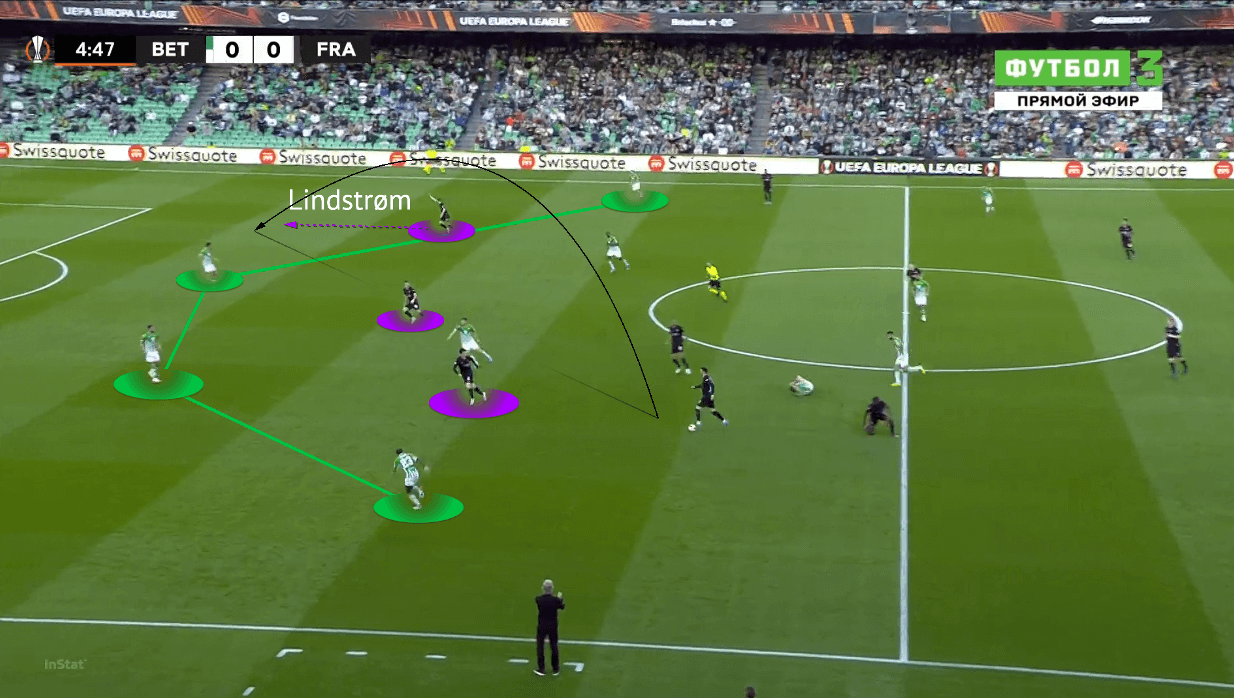

The above image shows Frankfurt’s shape in a 3-4-1-2, we use this as an example because it demonstrates the way defended very well. The 10s, Kamada and Lindstrøm were more orienting themselves towards the Betis centre-backs, but Glasner also wanted to shut down the central access of opponent to force them outside, so Borré was always on the Betis 6. When Pellegrini’s side use a 2-1 shape in the build-up, Frankfurt became a 3-4-1-2 in the defence.

This Bundesliga side was very good at closing the circulation path of the opponent because they have a far side attacker lurking high to catch the lateral passes. In this case, when Lindstrøm pressed, González could only go outside, ignoring Pezzella, who was asking for the ball, because Kamada was high to bait that pass.

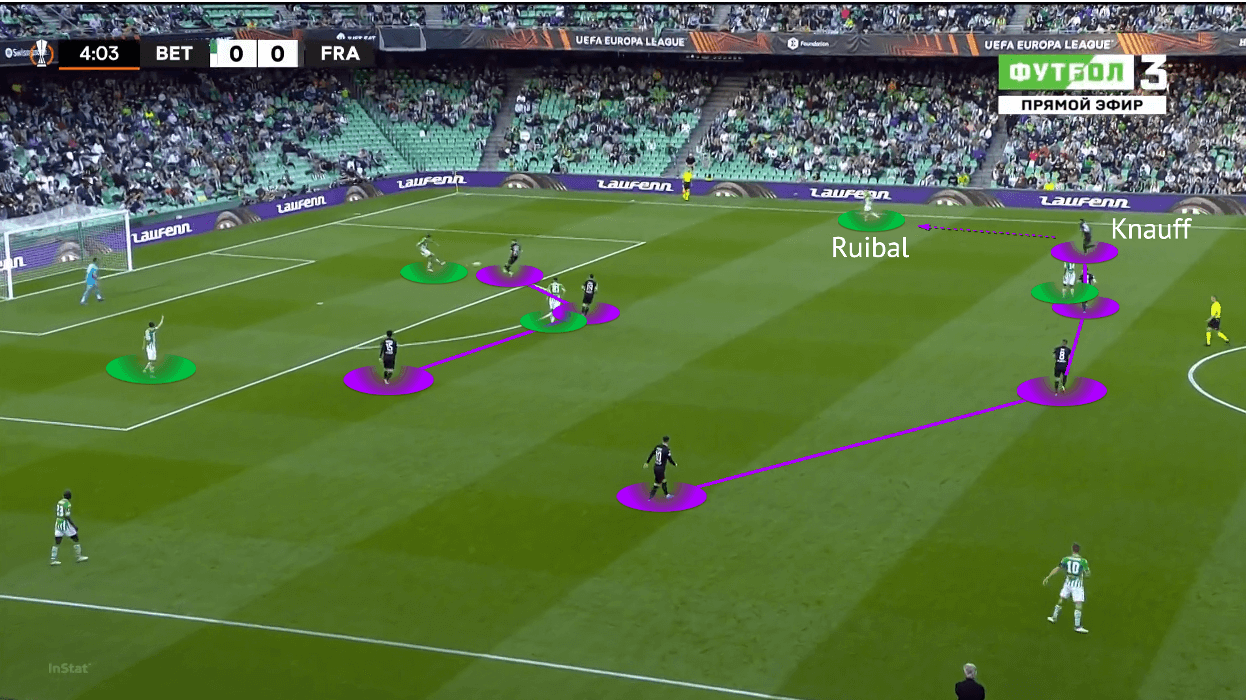

Although Frankfurt did not close the full-backs in the high pressing, they rather treated that CB-FB pass as a trigger of the press. This was a situation which the wing-backs should jump aggressively onto the full-backs, as Knauff would go all the way to pressure Ruibal in this situation.

We have a better picture of the wing-back pressing action in this example. Since Betis could change to a back three by dropping a 6 when they figured out the 2-1 shape was not optimal, that stretched Frankfurt’s first line into a 5-2-3. Usually, Rodríguez dropped into the first line while Carvalho and Fekir operated between the first and second defensive lines, the shape was reflected in this screenshot.

The Frankfurt 10s did a lot of pressing the keep the intensity, as Lindstrøm went to close the first line, forcing the pass to outside where they could continue the press with the help of the touchline. When the pass was made, Knauff, the wing-back, jumped out to close Ruibal as we explained. And see Glasner’s gesture! This was exactly what he asked the wing-back to do, he was calling Knauff to action as well.

When Betis played a back three, their best solution was usually Canales as the former Real Madrid man was a “false-winger” – a type of player that Pellegrini liked to use. When he dropped from the right-winger position to the midfield, he became an extra man to receive outside of the Frankfurt formation, as shown above, then he could turn and face the opposition goal.

But this progression route was not consistent as Frankfurt could also commit a centre-back, mostly N’Dicka to close Canales and balance the midfield – so actually no real damage has been done with this tactic, and Betis’ progressions were relying on Fekir’s. The former Lyon attacker was on fire and played like a “mini-Messi”. On average, he provided 2.57 progressive runs per 90 this season, and he had five in this game, which shows he lifted the game to a high standard very recently.

Transition threats

Apart from the offensive constructions and the pressing, the Frankfurt 10s also had a great part in the transitions from defence to attack (TDA), which kept Betis’ backline engaged throughout the game and that also posed threat when Pellegrini’s side committee more man to attack.

As the above section might have hinted, the Frankfurt 10s were mostly leading the press, but the real personnel who captured the ball were usually the players behind them, such as the centre-backs and 6s.

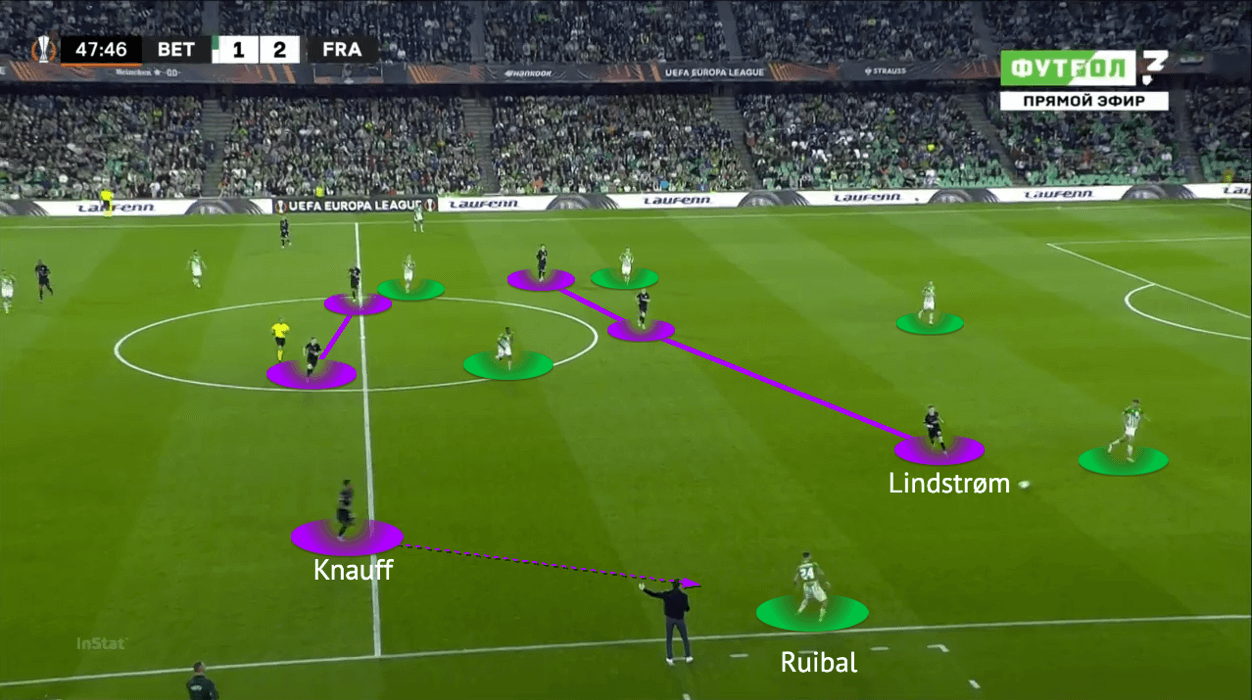

The advantage of such a setup was to have the 10s high in the TDA once the ball was recovered. Since Betis full-backs, Ruibal and Sabaly both pushed high and wide in the attack, they inevitably conceded those spaces outside of the centre-backs in this phase, this was where the Frankfurt 10s could do harm.

For example, the above image shows Frankfurt winning a midfield battle, and see where Lindstrøm began the TDA action, he was already way behind Ruibal! One lofted pass could already send him to the final third and Lindstrøm could use his skills to take on the centre-back, testing the opposition when the defensive was not organized.

By having the 10s in the TDA, Frankfurt managed to keep the counter-attacking until the last kick of the match. Their striker, Borré, often dropped to pull a defender out in the initial action, which could create spaces behind to attack. So even Betis could have the full-backs deep in the construction, the same spaces could still be conceded with this movement.

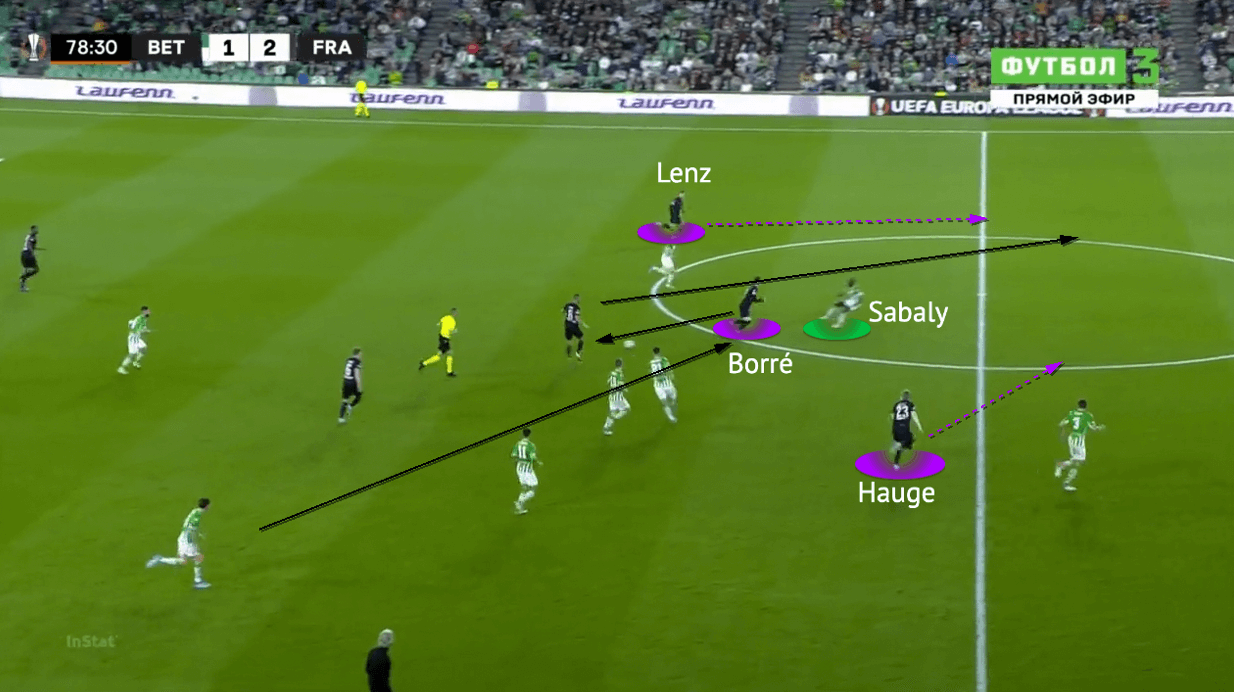

Here, Sabaly was pulled out by Borré, and see the positions of Frankfurt 10s, Christopher Lenz and Jens Petter Hauge were already going behind. That’s why Glasner made changes in this position by putting Lenz, Hauge, and Kostić to replace Kamada and Lindstrøm, he wanted to keep the threat by his 10s to see whether they could get one more goal from Betis, but Claudio Bravo’s strong second-half performance denied it.

Conclusion

As we have shown in this analysis, Frankfurt 10s were important to Glasner’s Frankfurt tactically. Their participation in all phases of plays were crucial in this victory and how they became superior to Betis. Kamada and Lindstrøm were different types of players but they offered alternative qualities in the attack was a complement to each other, and the commitment they had without the ball was also very good. Frankfurt were fortunate to have both players in the squad to implement the tactics Glasner wanted.

Comments