This tactical theory will analyse different pressing structures and how they have led to teams creating goalscoring opportunities.

These structures are designed to prevent teams from advancing up the pitch and demonstrate how to turn the opposition's possession into chances and goals for your team.

This tactical analysis will include Celtic’s tactics with their aggressive press against Bundesliga side RB Leipzig and Motherwell’s defensive set-up against the current Scottish Premiership Champions.

Also included is how other Champions League forwards have positioned themselves to score from attacking transitions when pressing.

Celtic’s Aggressive Press

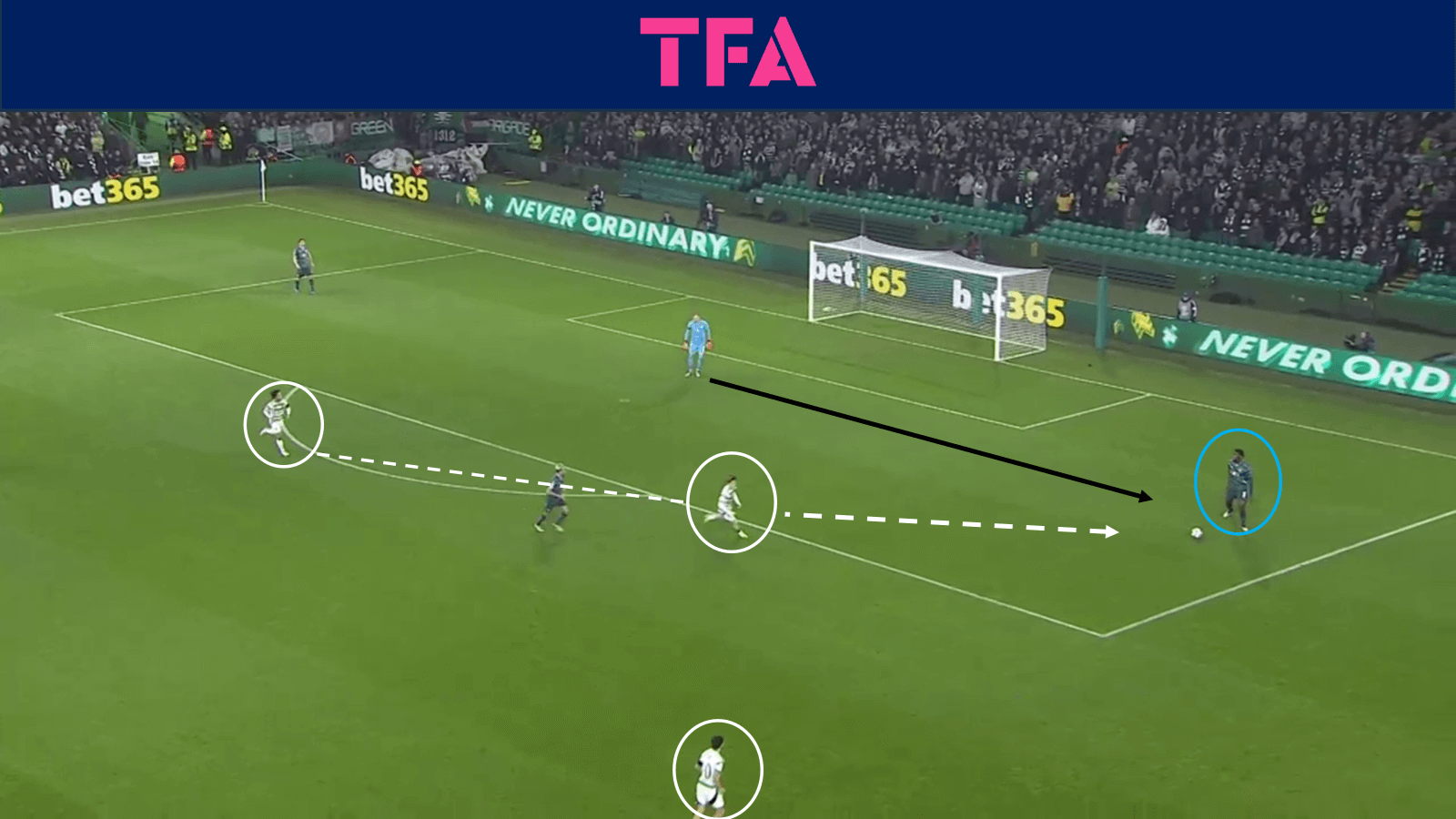

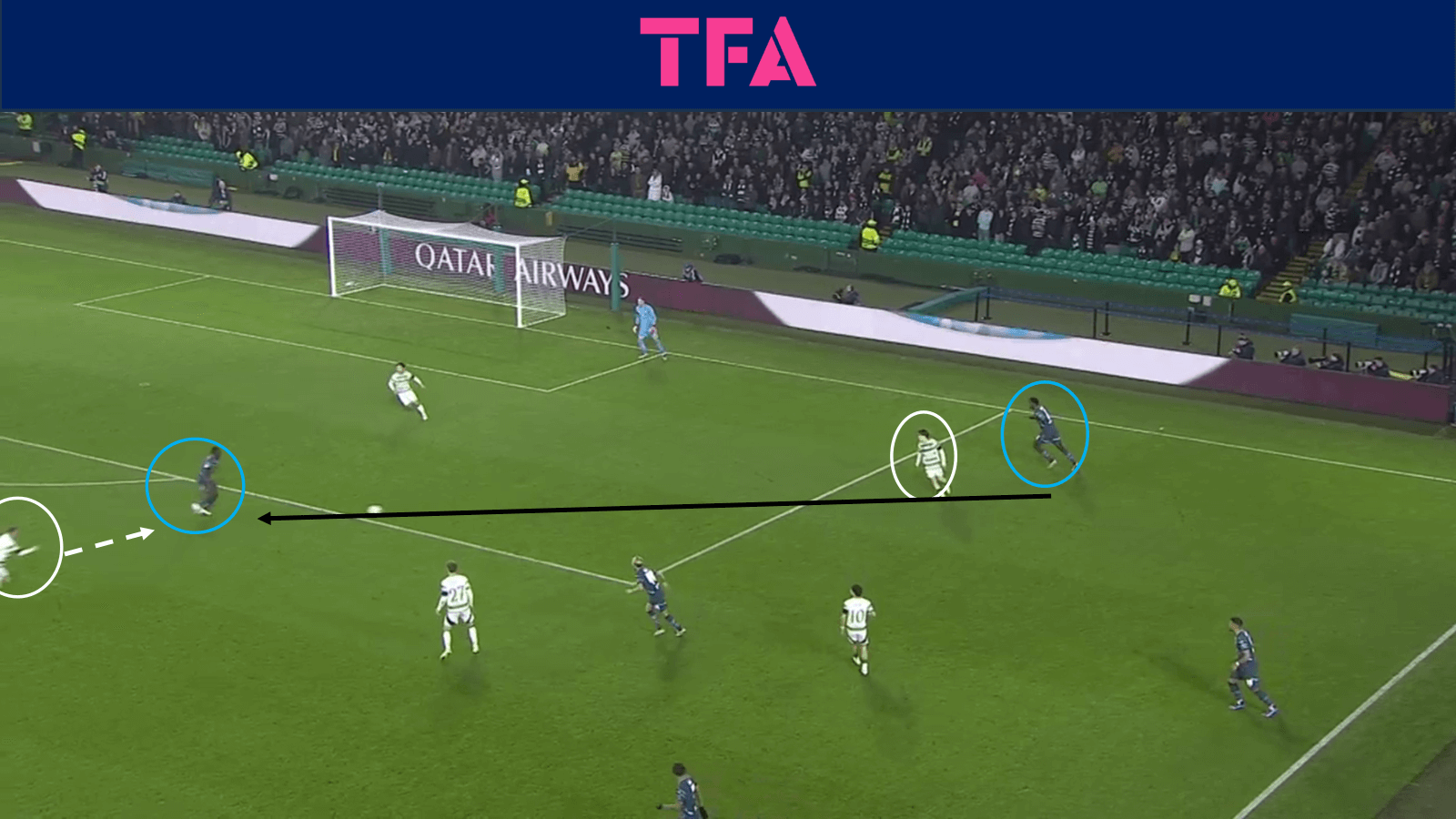

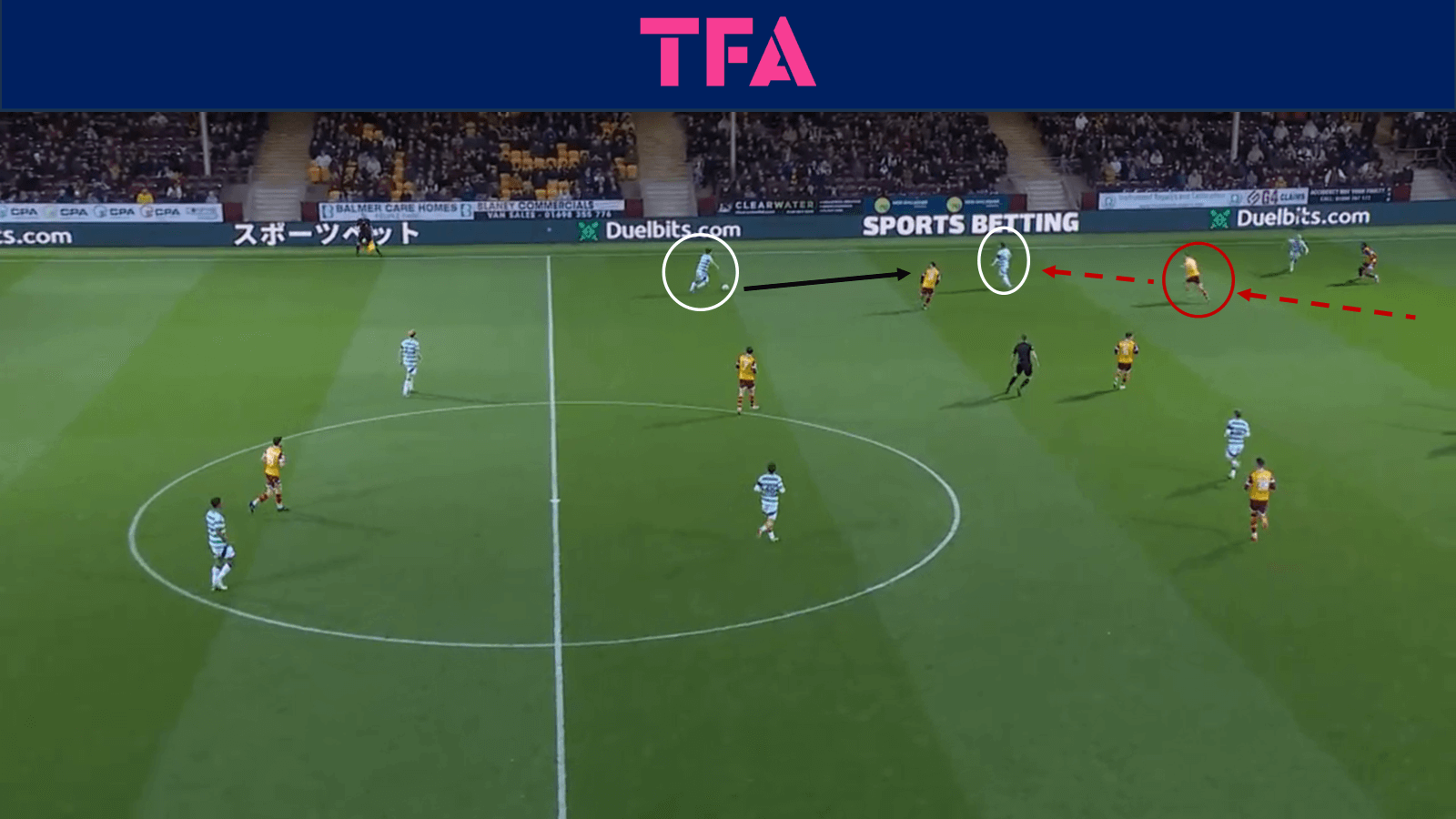

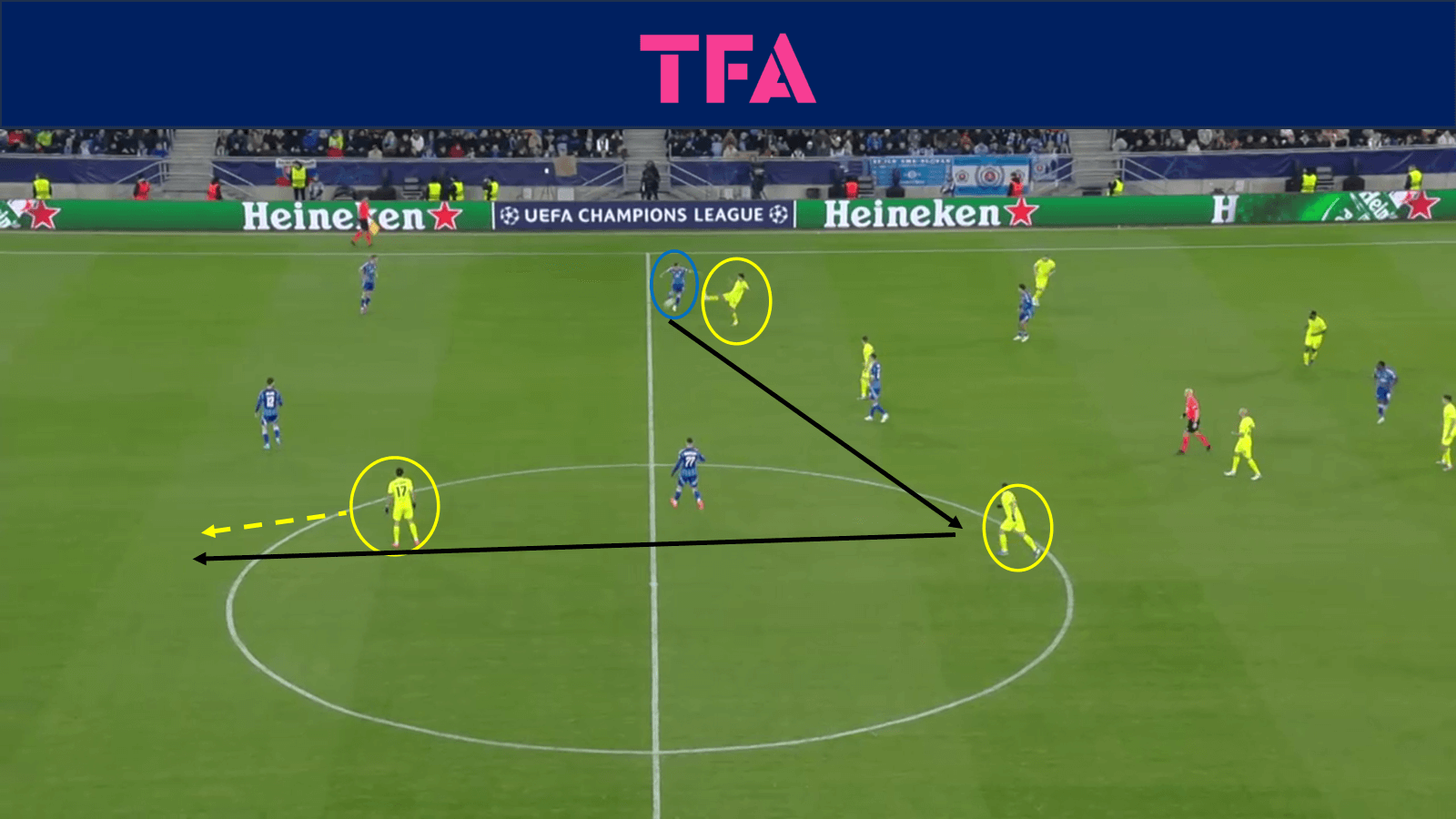

The above image is from Celtic's recent 3-1 Champions League victory over RB Leipzig.

In this game, Celtic were praised for their high, aggressive press and rewarded with a goal.

This example shows Celtic’s set-up just after the ball has been passed from the Leipzig goalkeeper to his left centre-back.

Celtic formed a 4-4-2 shape with midfielder Reo Hatate stepping up beside striker Kyogo Furuhashi.

Right winger Nicolas Kühn and left winger Daizen Maeda (just out of shot) were positioned slightly deeper than their now front two, just outside the width of the box.

By having two players narrow when the goalkeeper on the ball was in comfortable possession or a goal kick, Celtic prevented Leipzig from playing centrally, specifically into their ‘6’.

Once the ball was played to the centre-back, the ball-near forward pressed the centre-back, with the ball-near winger responsible for either cutting off passes or closing down the full-back.

Leipzig's reaction to this set-up was to drop their full-back much lower, as deep as the edge of the box.

This meant Kühn had to jump much higher to press the left-back, leaving more space behind him that Leipzig could exploit.

The knock-on effect was that the ball-near forward was unable to be positioned to simultaneously prevent a pass back to the goalkeeper and be set to press the ball-near centre-back.

Instead, the forward had to remain closer to his winger to prevent Leipzig from being able to find one of their midfielders in the bigger area of space that they had created behind Celtic's first line of defence.

By the forward, initially, and now also his nearest central midfielder, closing the space behind their winger, Celtic forced Leipzig to play backwards.

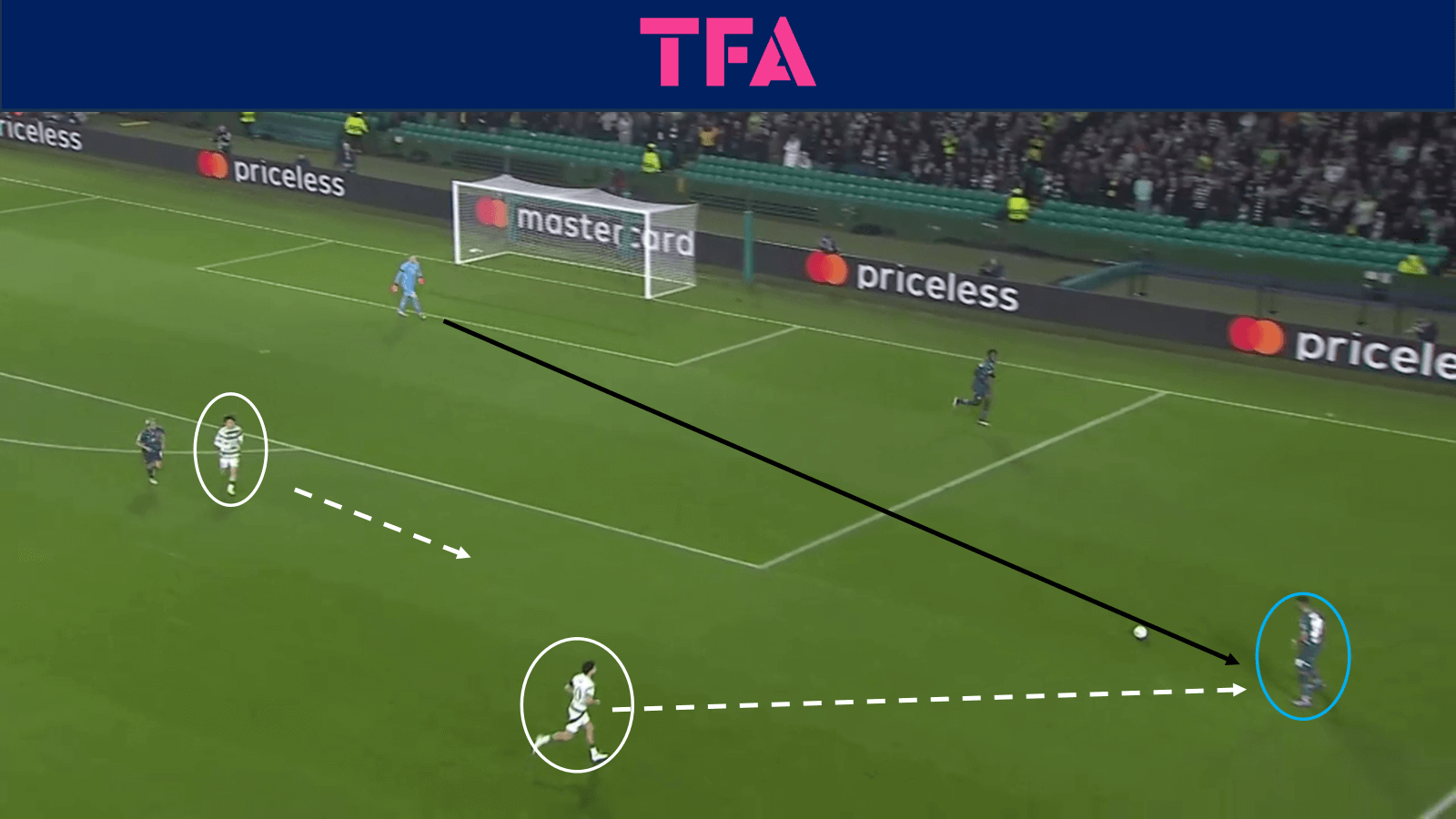

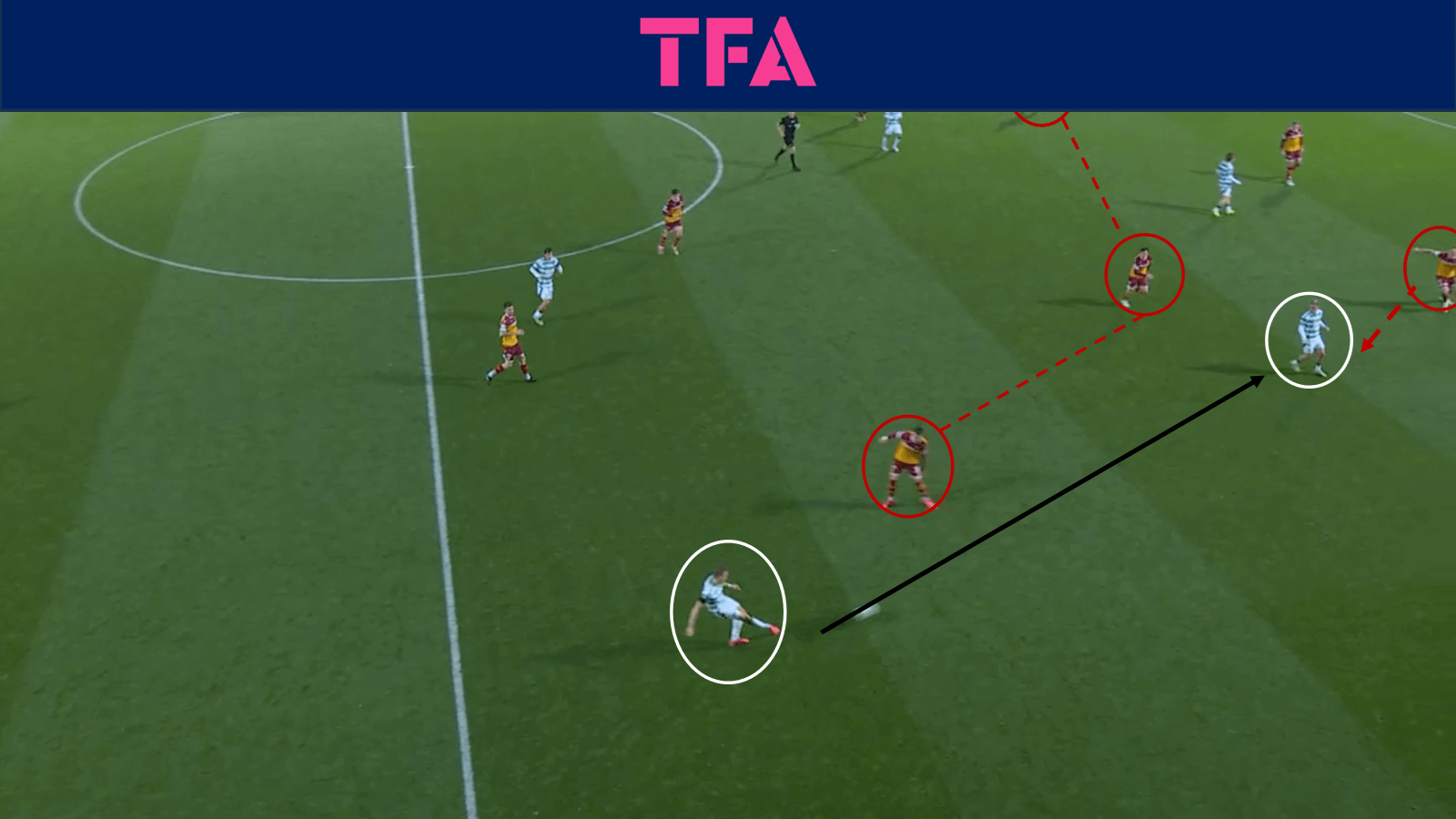

This backwards pass from full-back to centre-back acted as a trigger for Celtic’s nearest central midfielder to step up to the opposition’s ‘6’.

The ball-far forward, Hatate, then moved centrally.

Again, this helped protect the middle of the pitch but had the main aim of positioning the forward to be primed to press the goalkeeper should he receive the ball back.

The angle of Hatate’s press here is important as, should the goalkeeper receive it, Hatate would be forcing him back to the same side that Celtic had now overloaded.

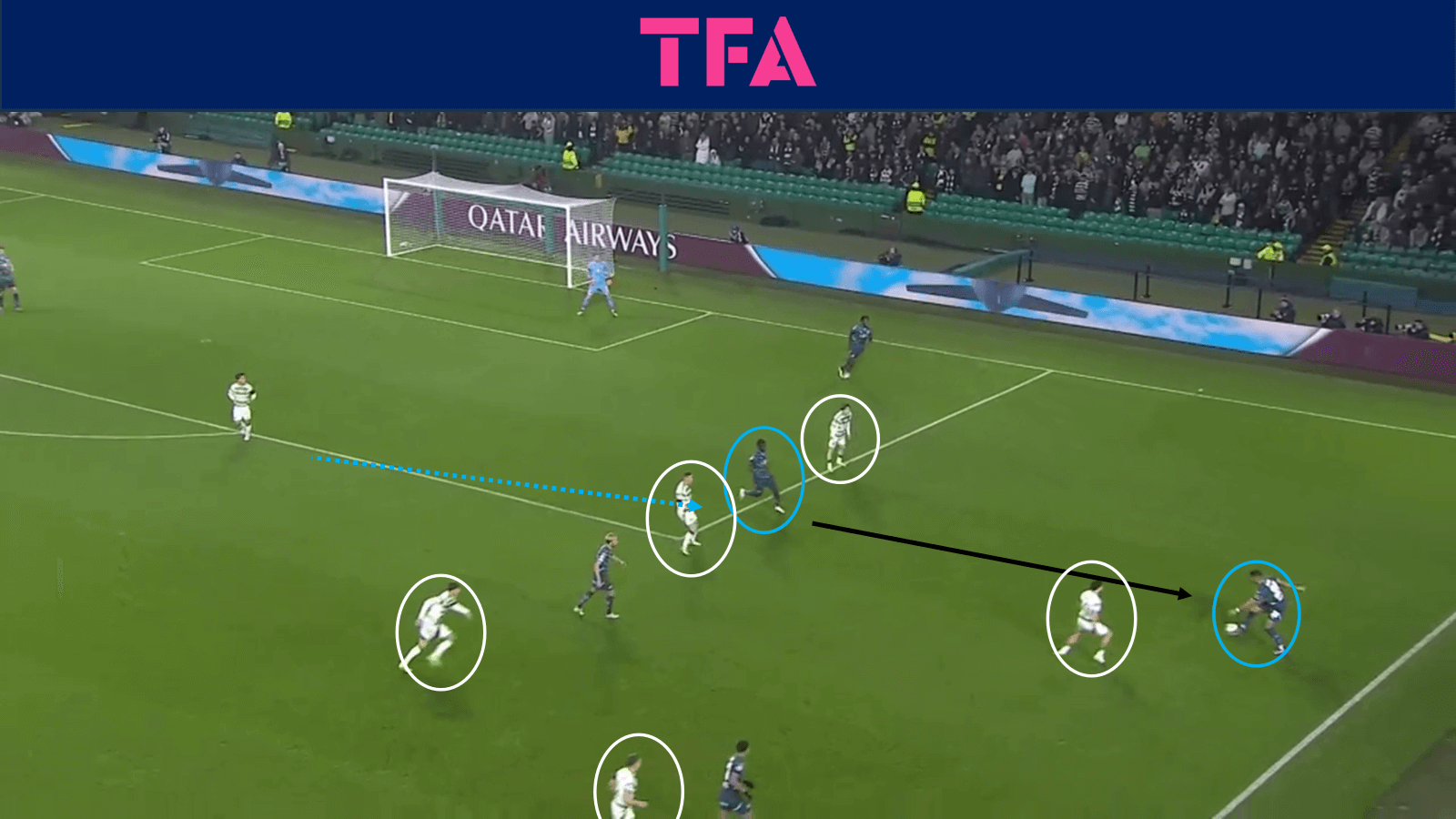

Even when Leipzig's composure on the ball allowed them to find a forward pass out of the immediate pressure, Celtic had a solution.

Here, the centre-back, initially shaping up to play to his goalkeeper, calmly moved the ball back to his left foot and found his ‘6’ on the edge of his box.

Callum McGregor, on the far left of the image, then stepped up aggressively to press the defensive midfielder.

As with the forwards’ press on the goalkeeper, McGregor angled his pressing run to force them back to Celtic’s right.

By forcing the midfielder to play back to where the ball had just come, Celtic surrounded the ball with five players in an area the size of a rondo box.

Celtic had firm pressure on the ball with touch-tight pressure on the opposition players around it.

This same scenario, albeit on Celtic’s left side of the pitch, led to them stealing the ball, quickly putting it into the box via a cut-back, and scoring their second goal.

Pressing From A Mid-Block

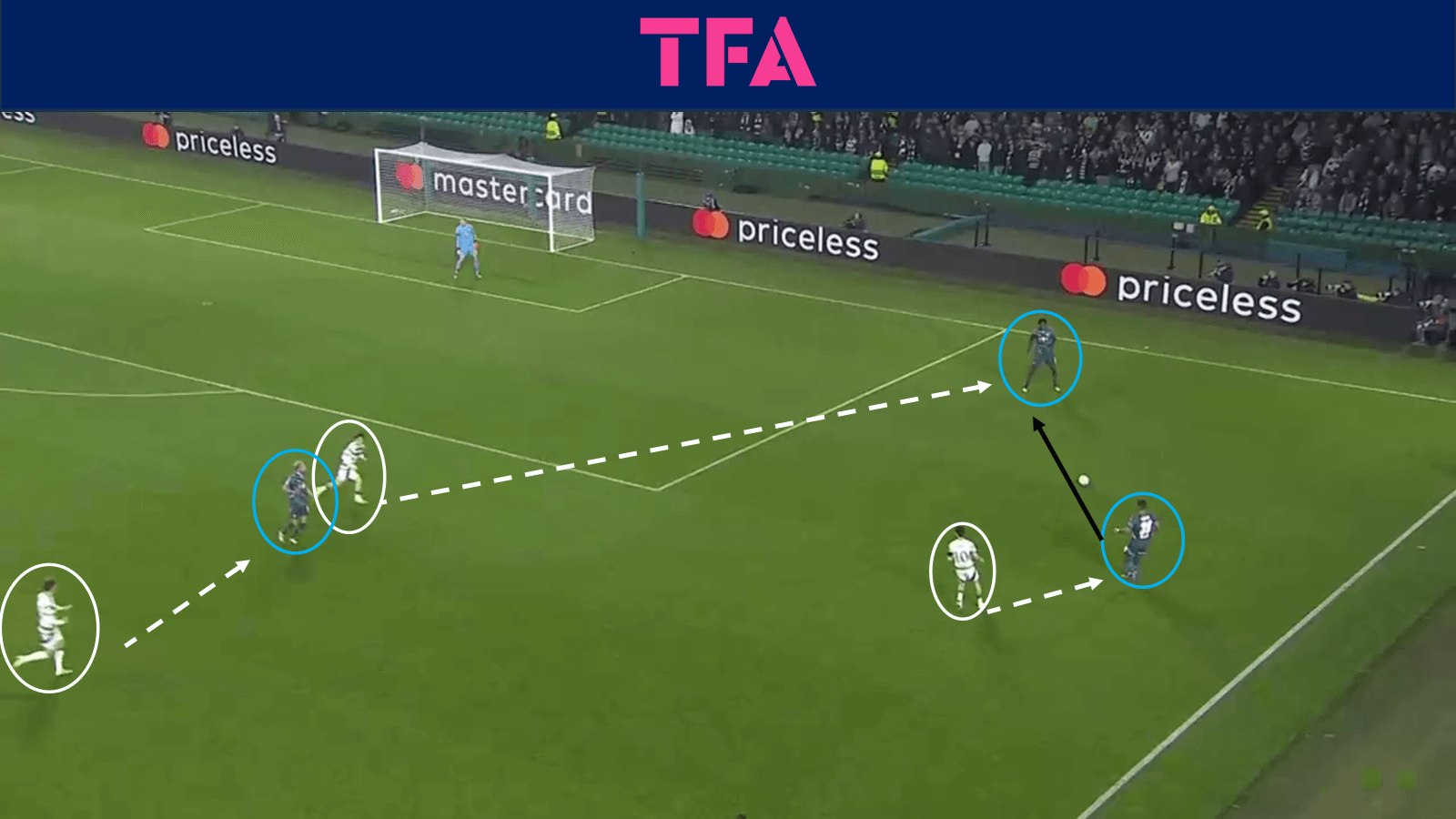

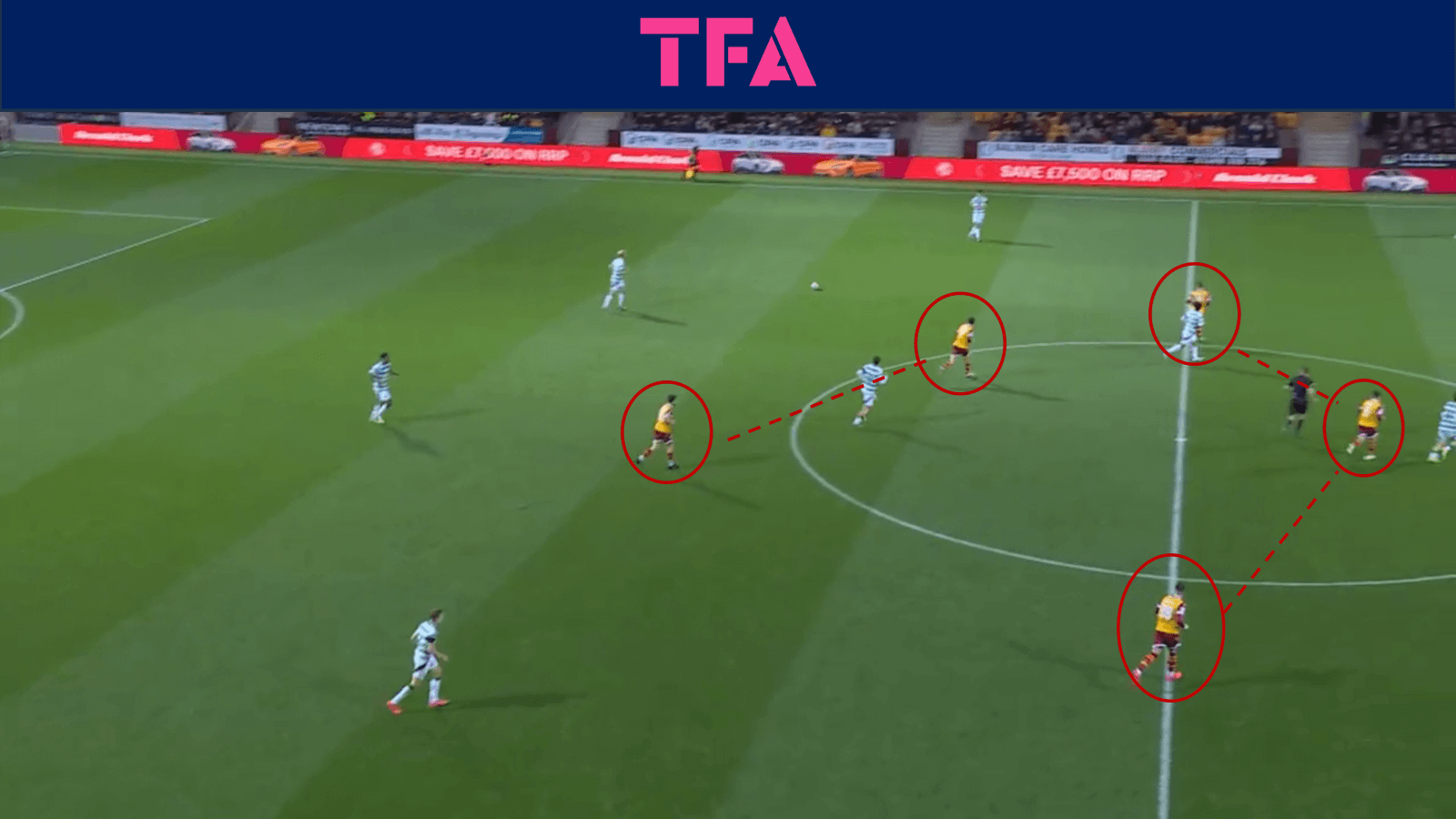

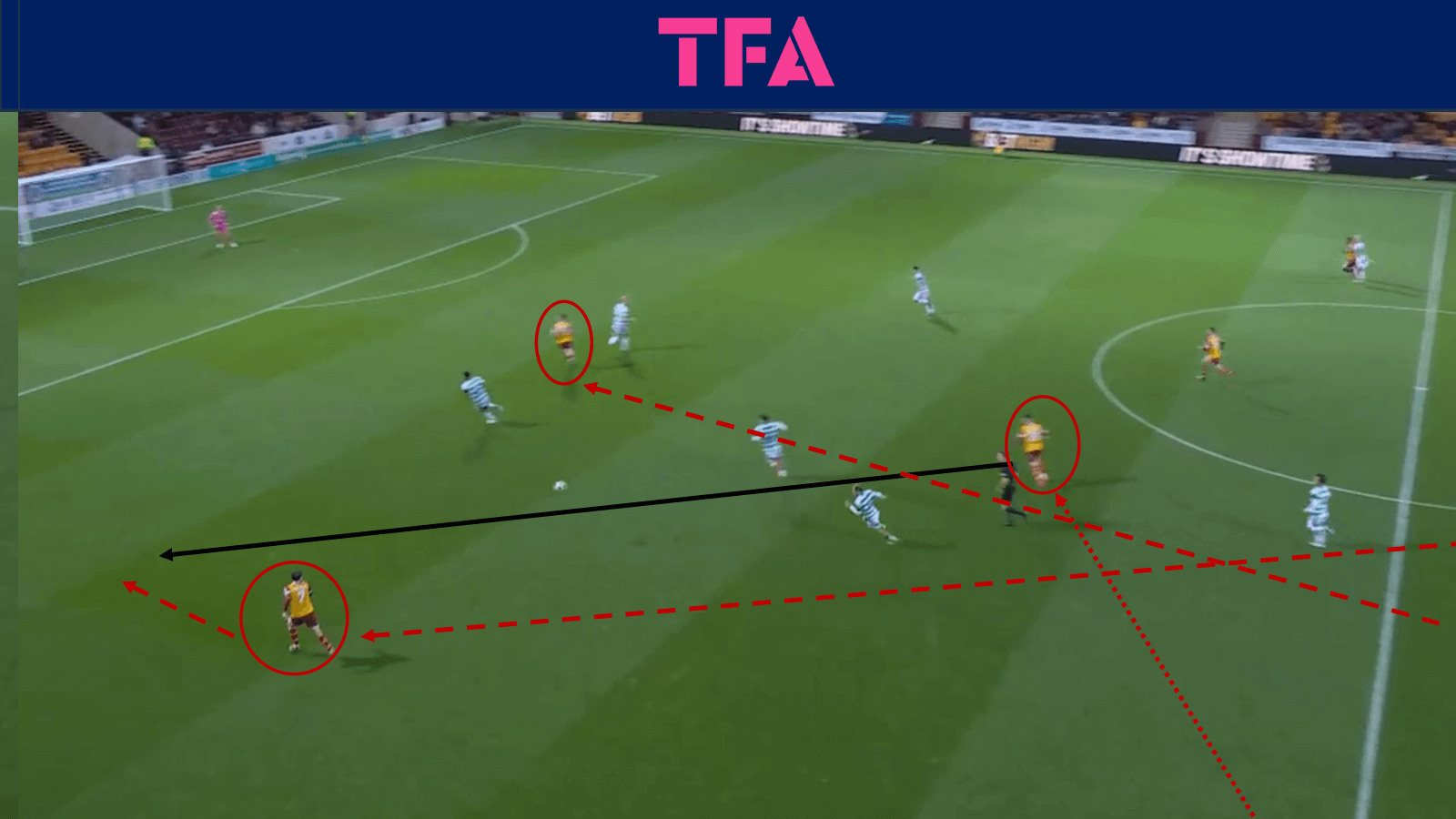

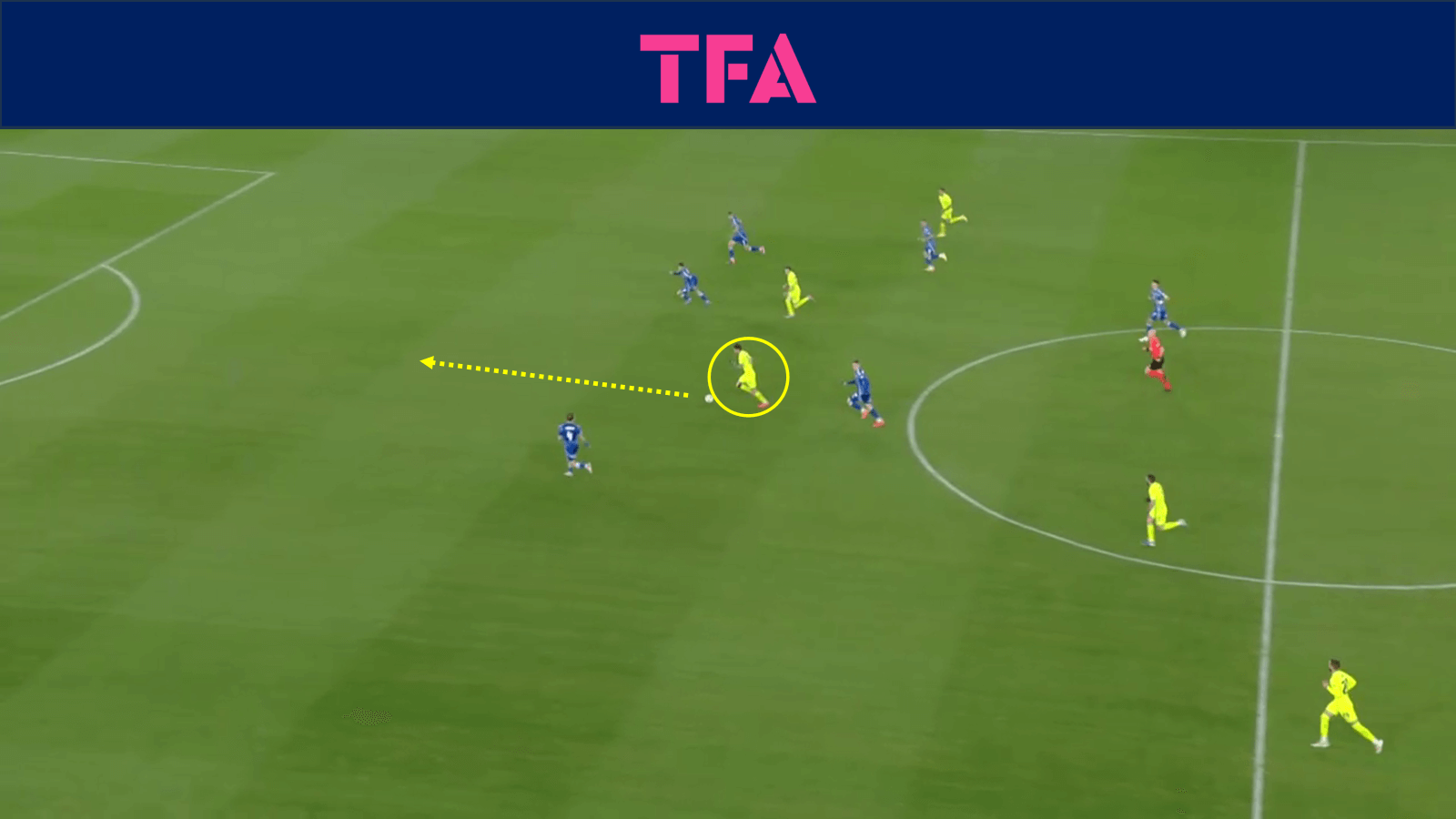

Unlike Celtic’s high press, Motherwell, playing against the league leaders, implemented a pressing structure from a mid-block.

Whilst setting up further from the opposition goal, it was often far more aggressive in its implementation than what is often typical from a mid-block team.

Just like their Champions League counterparts, Motherwell had a clear plan of attack when possession was won.

As the image above shows, Motherwell’s set-up with a front two and three central midfielders behind them.

The forwards pressed in a diagonal line, along with the widest midfielder, to secure the centre of the pitch and force Celtic to one side.

Behind the forwards and midfield was a flat-back five.

As shown in the above scenario, this time with the ball on Motherwell’s left, their wing-backs did not jump when the ball was played into the wide area in the middle third.

Instead, they remained connected to their centre-backs and allowed the side midfielders to press all the way to the wide area.

This could have resulted in the midfield three having to constantly run side to side and cover unmanageable distances because they trapped Celtic so successfully on one side that they only had to run once.

When Celtic’s midfielders were able to open up into positions to receive, Motherwell’s ball near centre-back (circled) jumped to press.

Here, Motherwell’s left centre-back, with the insurance of four defenders remaining behind him, pressed the ball from the inside out, on the opposition's blind side as it was travelling.

This image shows the same scenario on the opposite side and leads to the centre-back winning the ball.

This is possible because Motherwell has a compact shape, with only 22 yards between front and back.

The team is so short that Motherwell's backline is secure without being stretched.

They have Celtic's midfielders closing down a distance of their centre-backs, allowing them to jump when the ball is travelling.

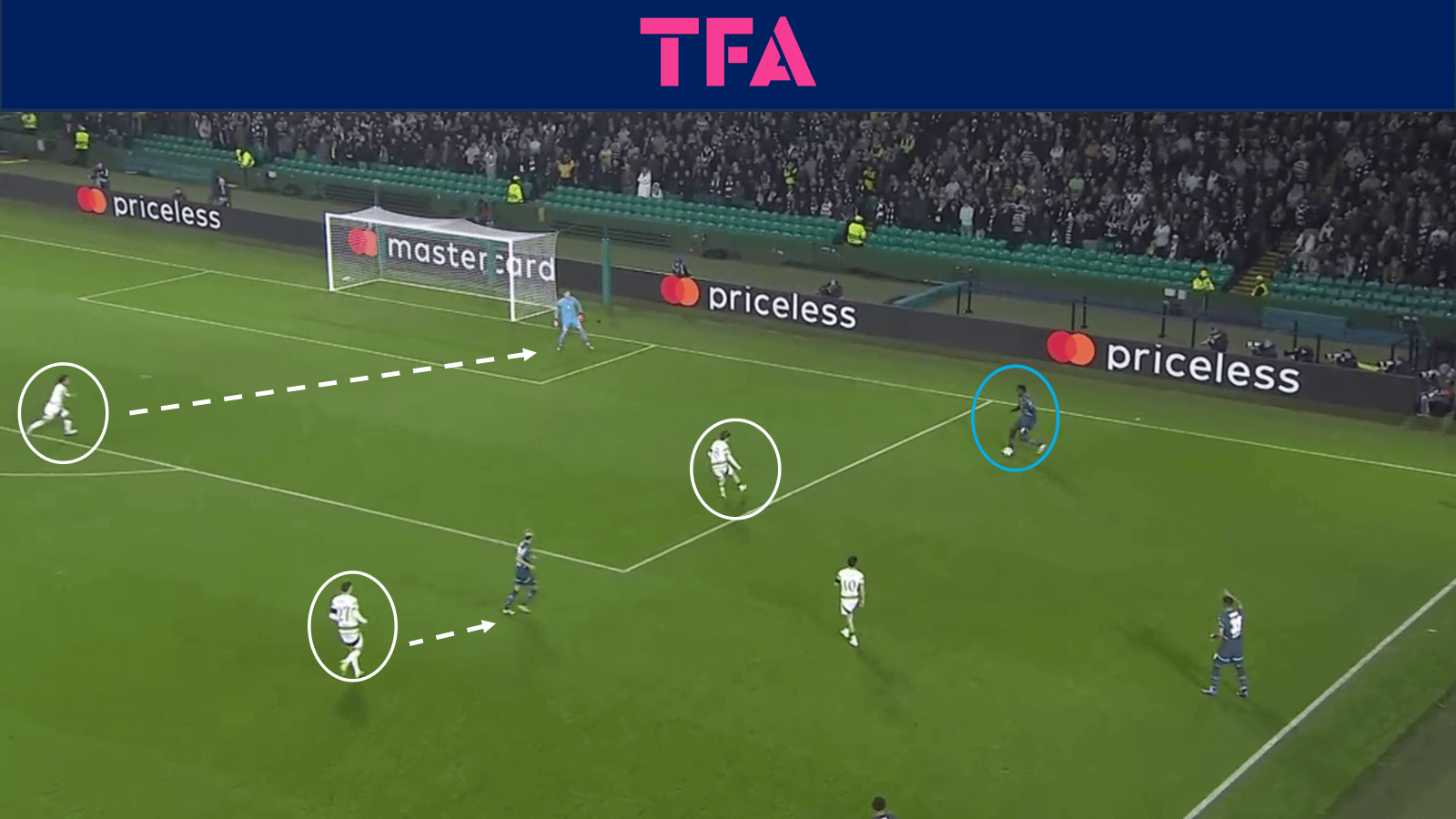

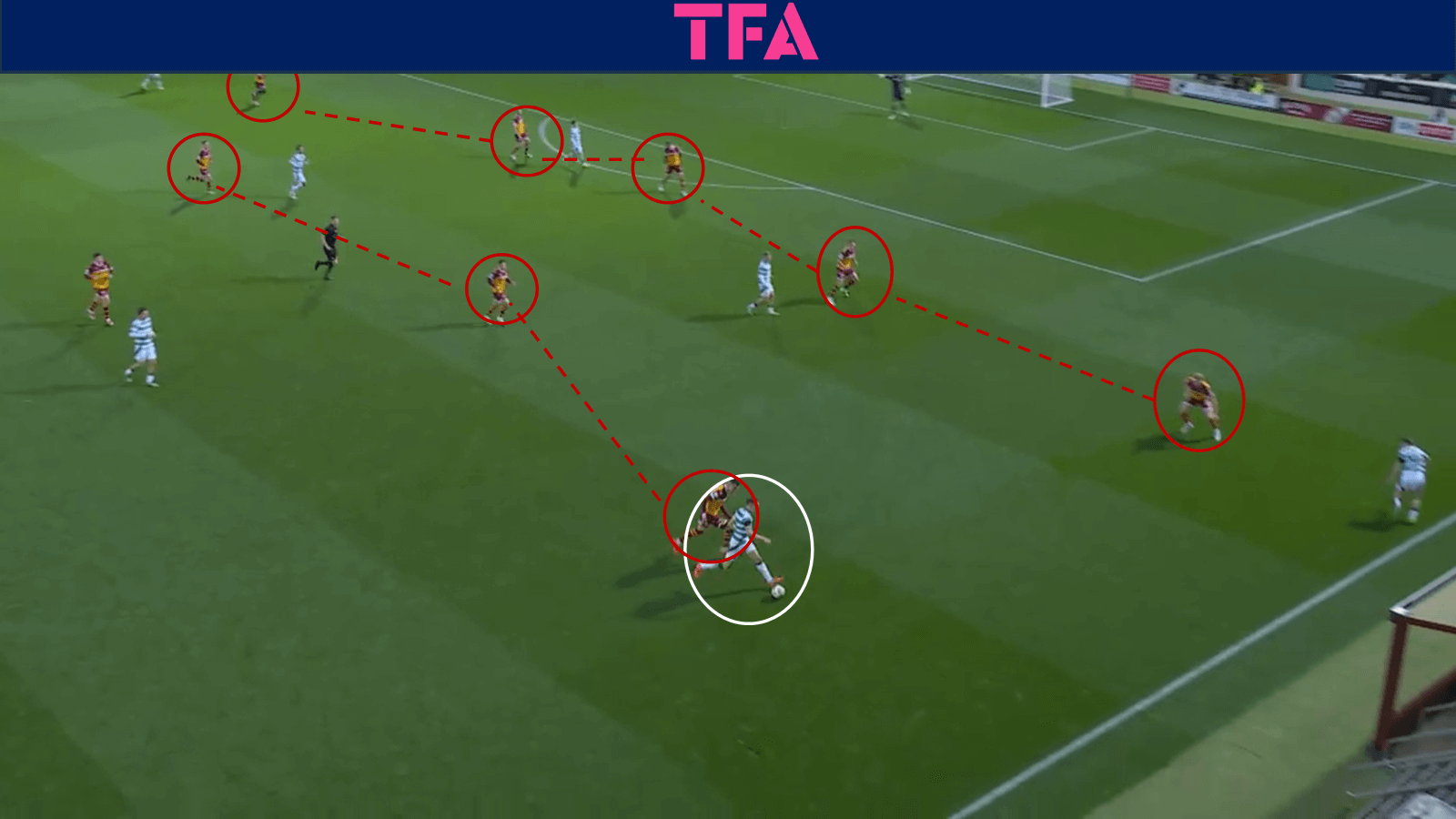

What to do when the ball is won is just as important as the structure.

Teams must clearly know how to attack when they regain possession when the opposition is at their most vulnerable.

In this image, which proceeded Motherwell’s centre-back pressing and winning the ball, the central midfielder (circled) immediately made himself available in the wide area behind Celtic’s advanced right-back.

The furthest forward of the two strikers also immediately ran in behind to push Celtic's backline back towards their own goal.

As Celtic's backline were retreating, thanks in part to the forward's run, the midfielder in possession burst inside with the ball.

When he made his diagonal run inside with the ball, his attacking teammate overlapped him with a diagonal run to the outside.

By dribbling inside with the ball, the midfielder opened up the entire pitch, making it very difficult for Celtic to press him.

The midfielder was able to play a pass into the path of his forward, but he was free because the centre-backs had to prioritise covering the more central forward.

The forward delivered a dangerous cross into the Celtic box, with all four Motherwell players in the image above bursting forward to attack the box.

Forwards Positioning

This section will analyse the positioning of forwards who are not actively involved in the press but rather take up positions that allow for devastating attacking transitions when their teammates win possession.

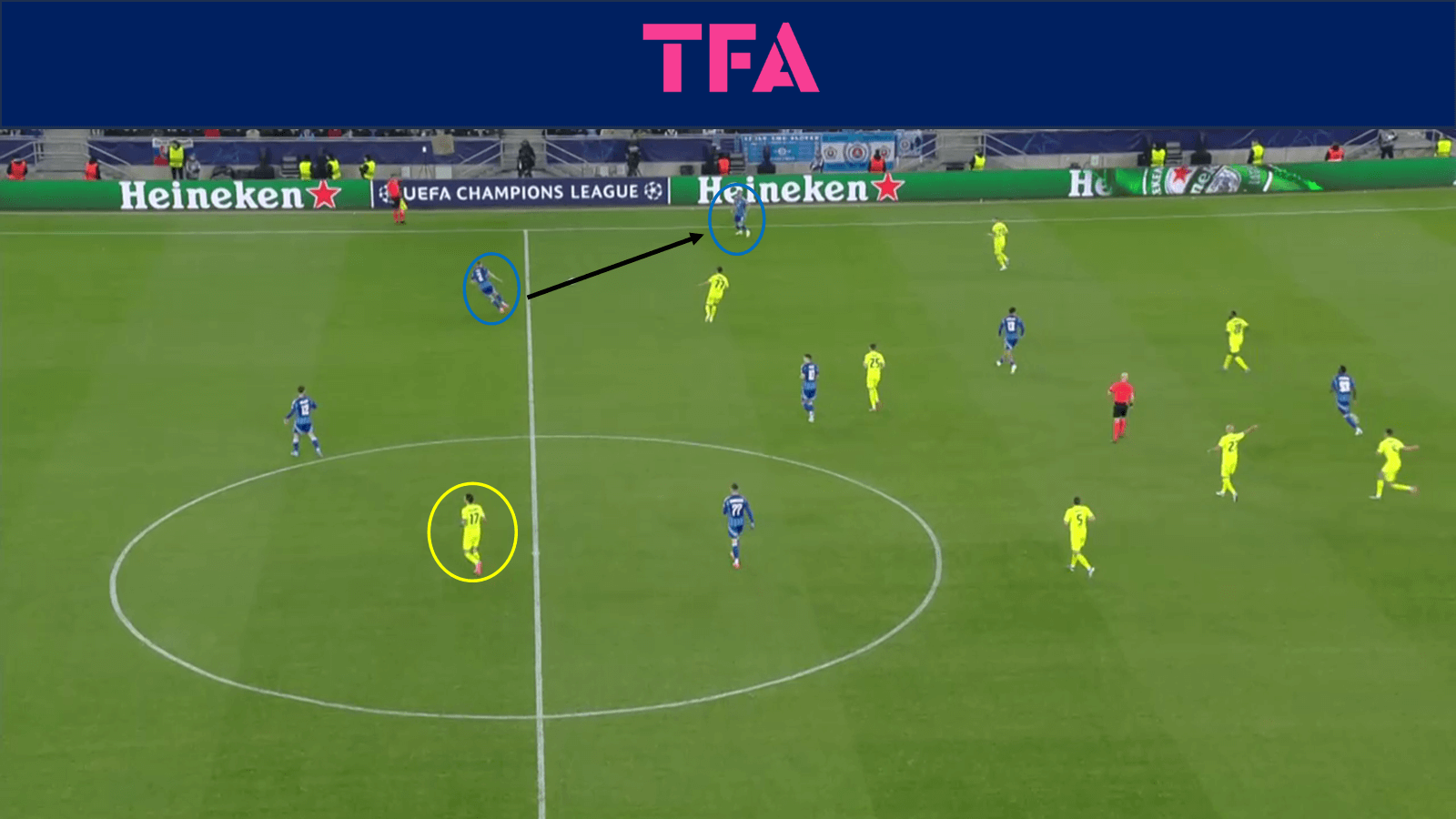

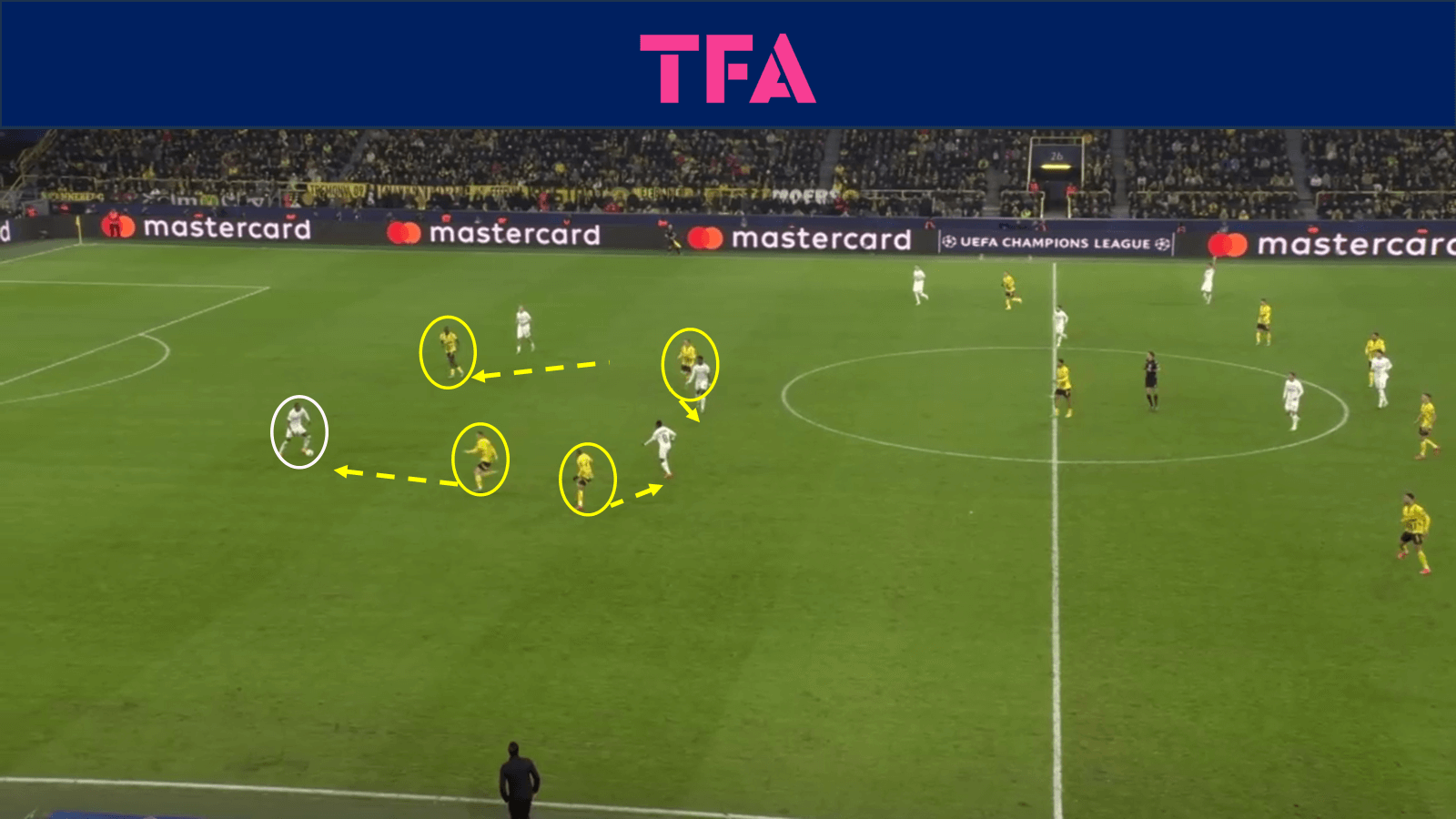

This image is from the build-up to Dinamo Zagreb’s fourth goal against Slovan Bratislava, who are in possession.

As we have analysed previously, Dinamo are shaped to force Bratislava down one side, which is a typical tactic.

Dinamo’s ball-far forward is positioned outside the opposition's ball-far centre-back.

Whilst not actively involved in the press, he helps keep the ball down his team's right side by making it uncomfortable for the far centre-back to receive.

Possibly, more importantly, he is also in a dangerous position should his team win the ball.

Frustrated by being trapped, the Bratislava full-back on the ball attempts a risky pass to switch the play.

Initially blocked by the nearest defending player, the ball arrives at Dinamo’s midfielder (circled) and is immediately played into the path of his striker.

Due to his positioning when the opposition had the ball, the striker had a vast amount of space and could drive with the ball right down the middle of the pitch.

The speed at which he attacks means Bratislava cannot recover and the play leads to Dinamo’s fourth goal of the game.

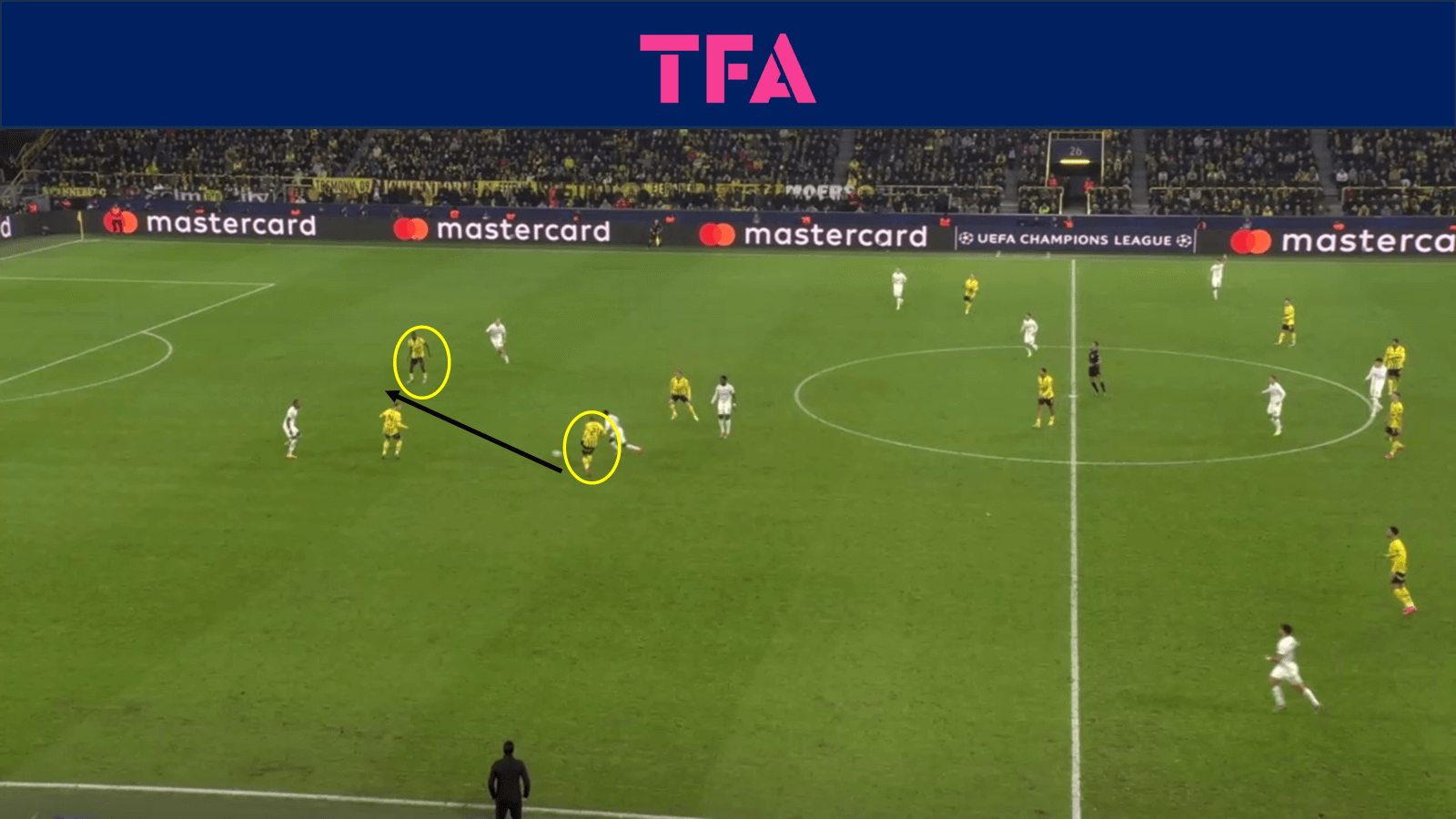

This image shows Dortmund’s Serhou Guirassy using a similar tactic, which led to their sole goal in their Champions League win over Sturm Graz.

With Sturm Graz’s centre-back in possession, three of the four closest Dortmund players to the ball closed down the closest player to them.

Guirassy, however, perhaps sensing the opposition were in danger of losing the ball, elected to move away from the ball far centre-back and position himself in the space between the two defenders.

When the ball was won, Dortmund immediately played into the feet of Guirassy, who was now in a very dangerous position.

Although the ball-far centre-back quickly reacted, it was not enough to prevent the striker from setting up the winning goal.

Conclusion

Pressing is now considered far more than just a means to prevent the opposition from advancing the ball up the pitch.

It is now, and has been for several years, viewed as a way of providing an “assist”.

Pressing structures should be designed with that in mind and provide players with a clear strategy of not just winning the ball back but with a path to goal.

This can be done in a manner like Celtic's, where they press as one unit high up the pitch and force a turnover near the opposition's goal.

It can also be done by sitting deeper and allowing the opposition to leave gaps in behind which can be exploited.

Another tactic is to leave a player who is not actively involved in the press, in dangerous spaces and feed them when the ball is recovered.

By introducing any of these principles into their pressing structure, teams can be solid defensively and turn their defensive structure into an attacking weapon.

Comments