Marcelo Bielsa’s Uruguay have not been at their best since the early games of this past summer’s Copa América.

In general, they have a stimulating style of play, but due to many injuries and suspensions, their performance levels have been dropping, and their systematic problems are in sight.

Uruguay were eyeing Copa América glory, and several stumbles made them complete a disappointing tournament, ending fourth.

Now, in the World Cup Qualifiers, they are third — five points above eighth place.

They have now gone five consecutive matches without a win.

It seems like the build-up structure is the beginning of their problems in possession.

In this tactical analysis and team-focused scout report, we will explore Marcelo Bielsa’s Uruguay game model, style of play, build-up structure, and problems in their tactics.

How Do Marcelo Bielsa’s Uruguay Play?

Marcelo Bielsa’s Uruguay starts from a 4-3-3 symmetric shape with some variations.

The midfield is divided into three heights.

Manuel Ugarte is the axis — the first passer in the build-up.

Federico Valverde is the second-highest midfielder on the right, while Nicolás de la Cruz is the advanced midfielder, usually on the left.

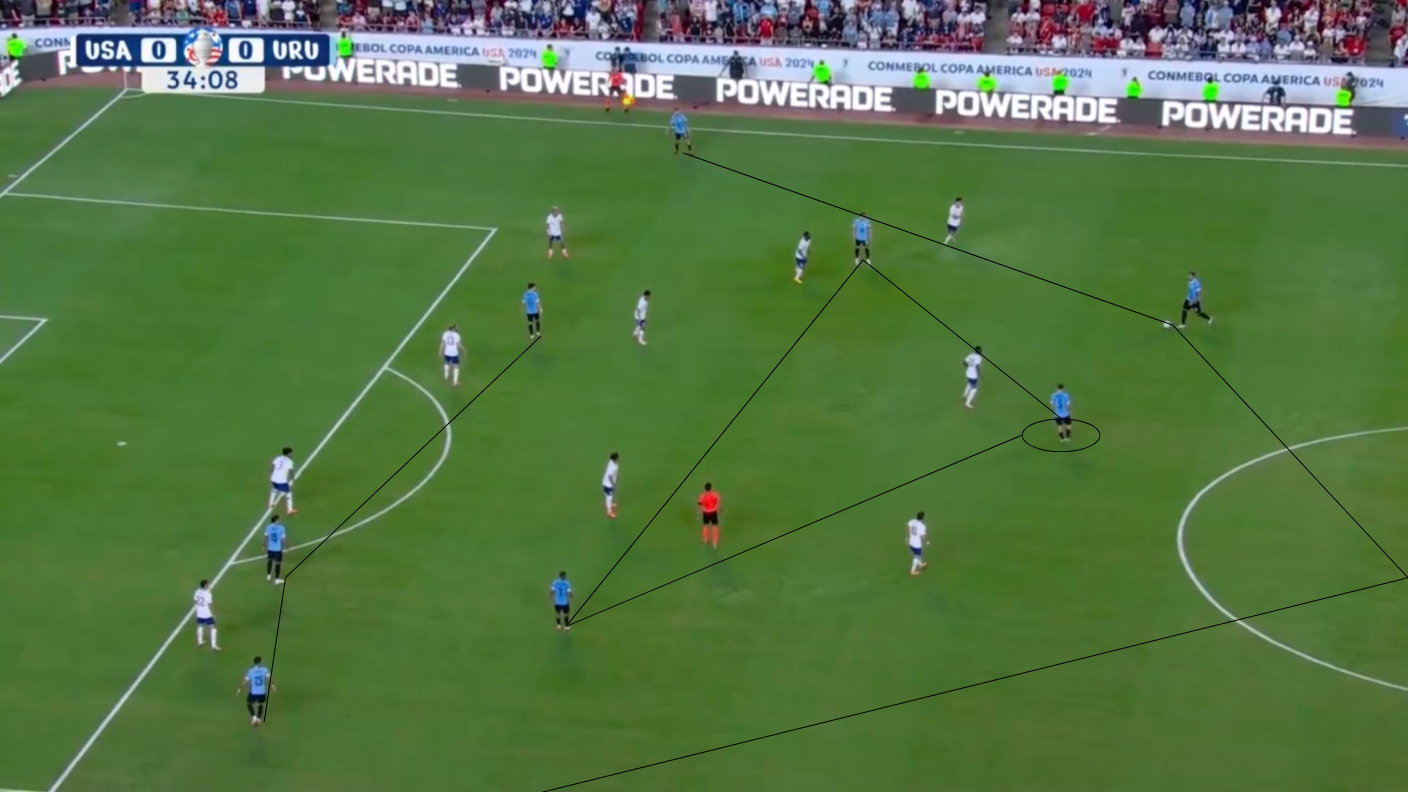

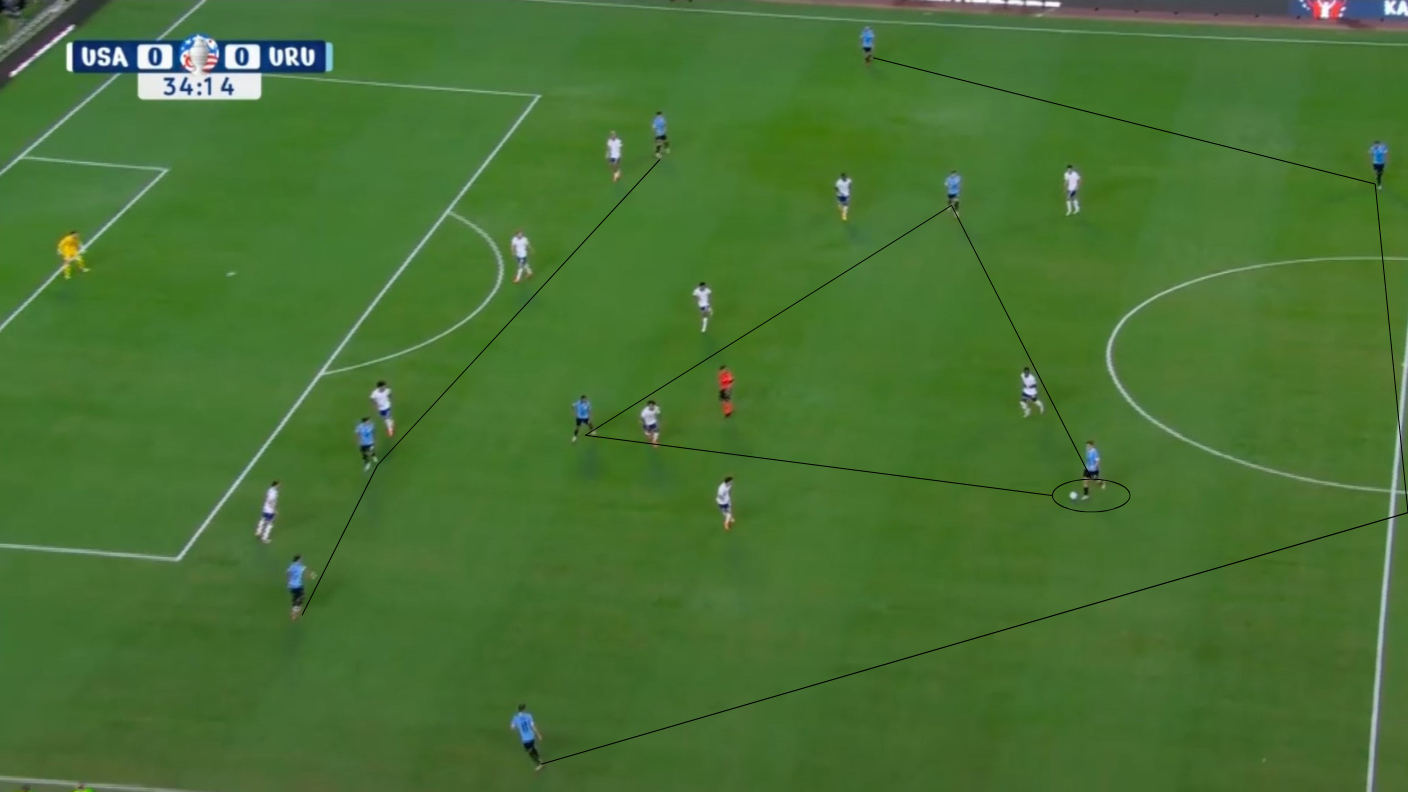

Like in the images above, Uruguay tends to play with a 4-3-3 formation, but this can change according to the behaviour of their midfielders.

Nicolás De La Cruz, Giorgian De Arrascaeta, and even Rodrigo Bentancur are capable of playing the advanced role.

Sometimes, the advanced midfielder moves forward, and Valverde accompanies Ugarte in a 4-2-3-1.

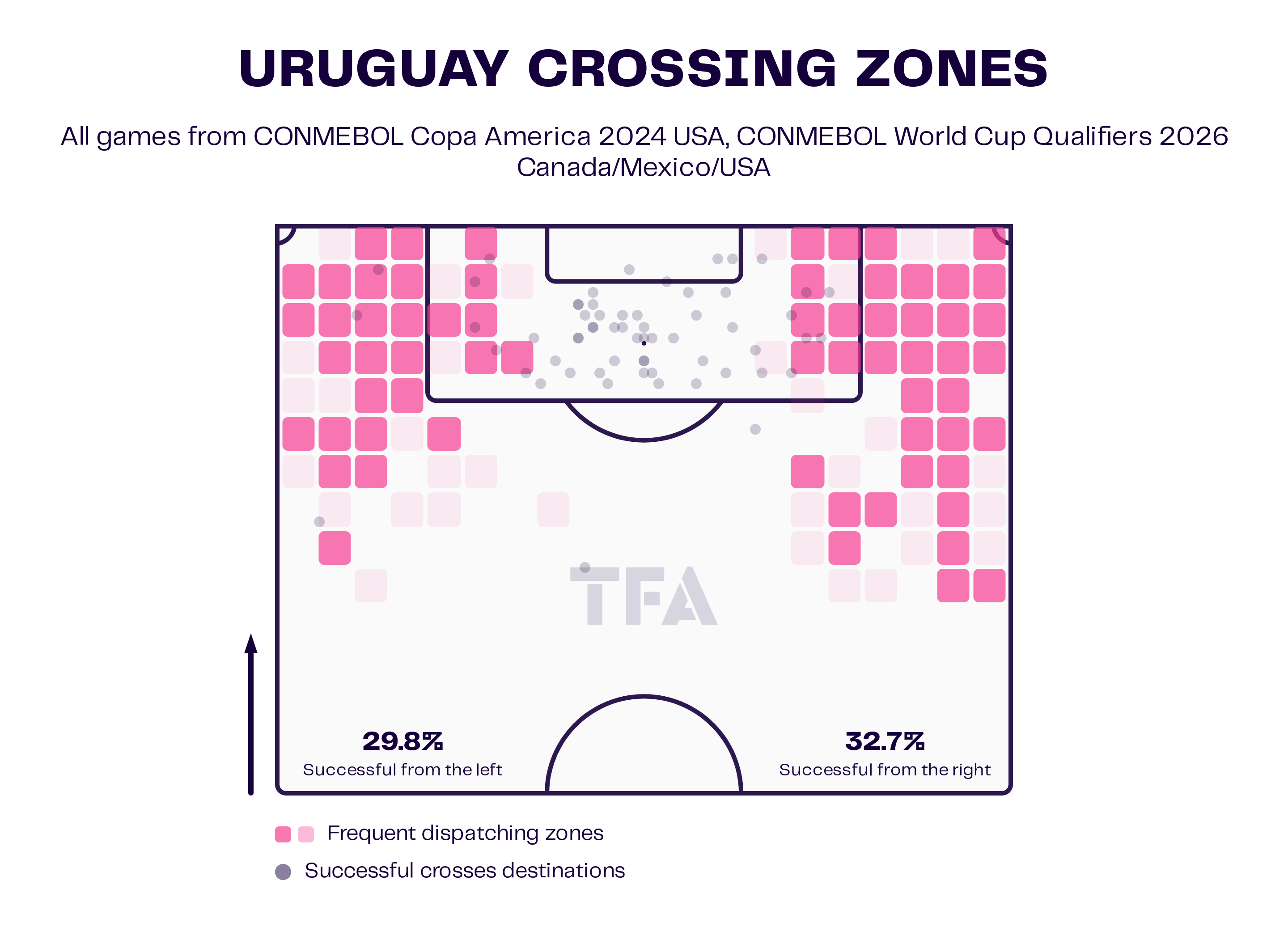

In that sense, Marcelo Bielsa has always chosen two natural-footed wingers in his team, Maximiliano Araújo (left) and Facundo Pellistri (right).

They do not have fantastic 1v1 ability or a variety of resources in possession.

They have what Marcelo Bielsa asks for in a winger: pace and crossing technique to arrive into the final third and feed their striker.

Along with Darwin Núñez in the attacking line, they offer a high volume of dismarking runs per match.

That is the focus of the attacking phase.

Once they recover or restart the play, many players offer dismarking runs to sink the opposition’s block and create potential crossing angles through positional advantages.

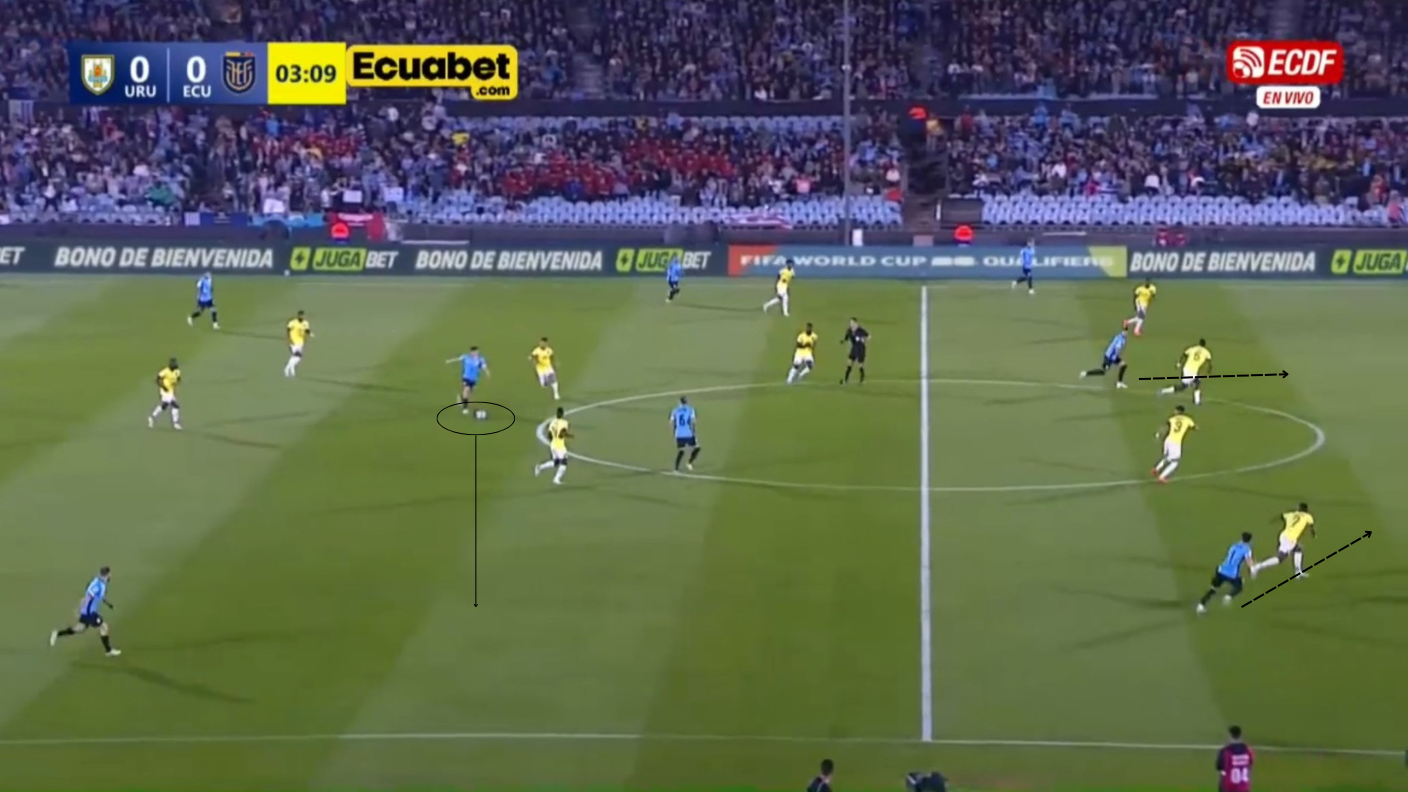

Figure 5 shows an interesting sequence when this happens.

When there is space behind, each attacker must run to attack it.

If the first disembarking run does not work, the next one will.

In Figure 5, Pellistri’s run did not work.

The opponent’s defensive line was very careful, but the next run (from Nández) created space and a potential crossing angle for the right back.

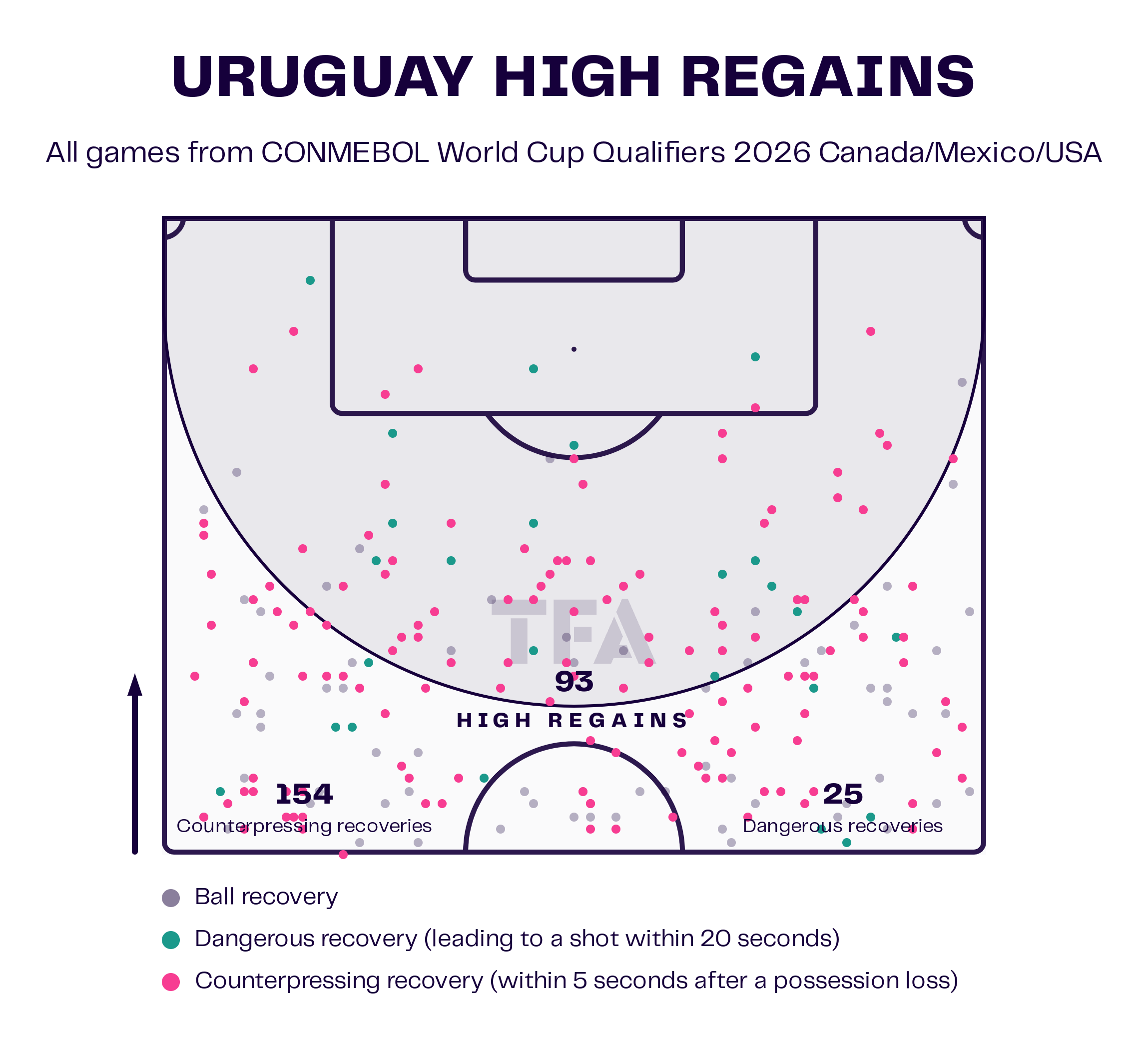

This is the most effective way for Uruguay to establish a foothold in the opponent’s half and implement a system of aggressive counter-pressing to recover the ball in advanced areas.

Uruguay’s Main Build-Up Issues

Taking into account Marcelo Bielsa’s game model and intentions with Uruguay, we can also understand that he needs risky passers to send long balls in behind.

And here we find the central problem in the whole system: the first passer (Ugarte) is not brilliant technically.

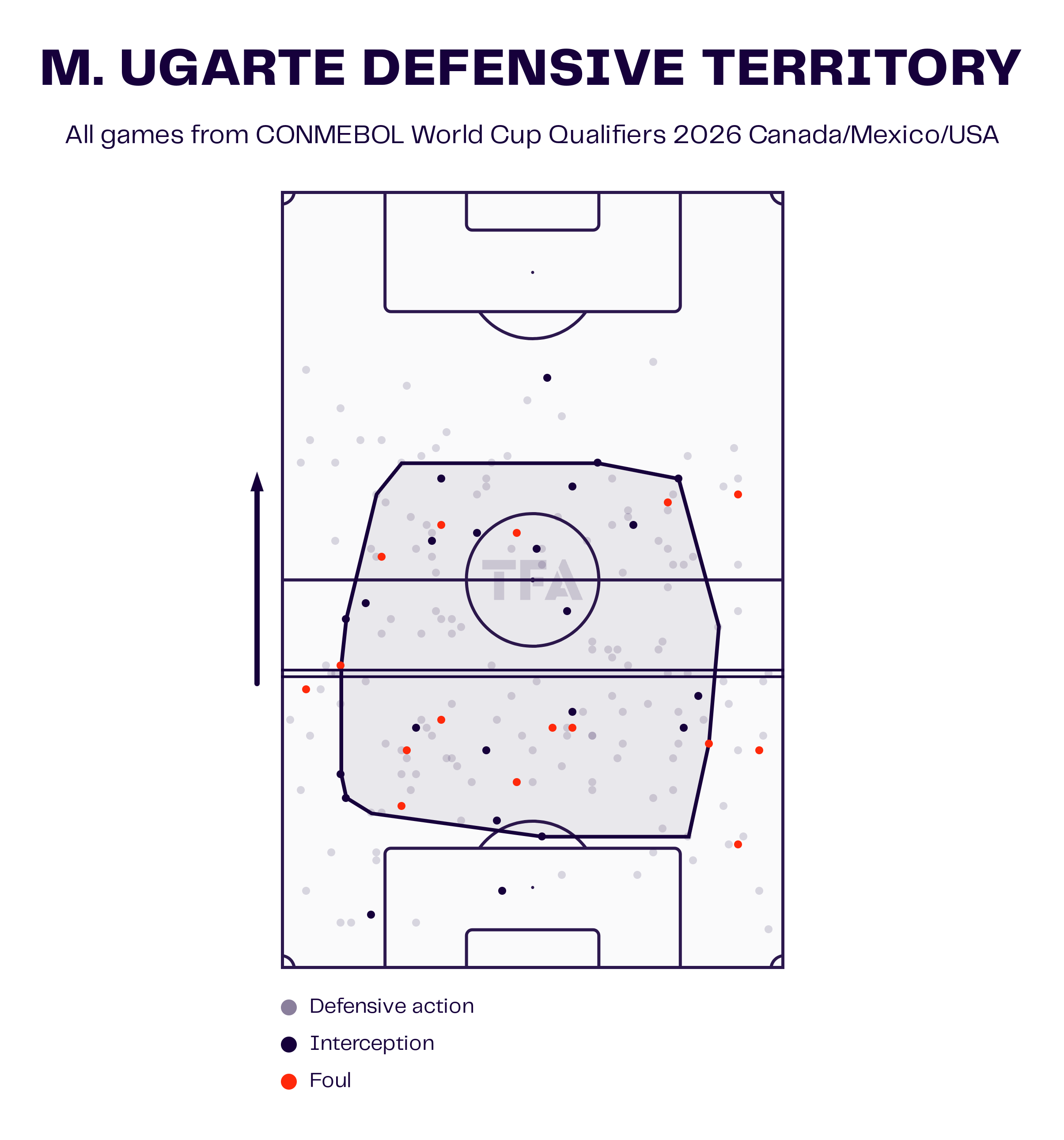

As outlined in this analysis piece (linked under the word ‘analysis’), Ugarte is a ‘destroyer’ among the different archetypes of defensive midfielders.

Without the ball, he is crucial for Uruguay—he provides security along his horizontal line, recovering and delaying many opponents’ attacks.

With this capacity to defend and counter-press man-to-man aggressively, Ugarte’s high volume of accurate defensive actions allows them to attack with many players in the opposition’s half, as we saw in their usual shape.

In possession is when Ugarte needs a plus close to him.

His passing range is not as varied as necessary in this playing model.

In terms of progress, Uruguay has been using other building sources to push the team forward.

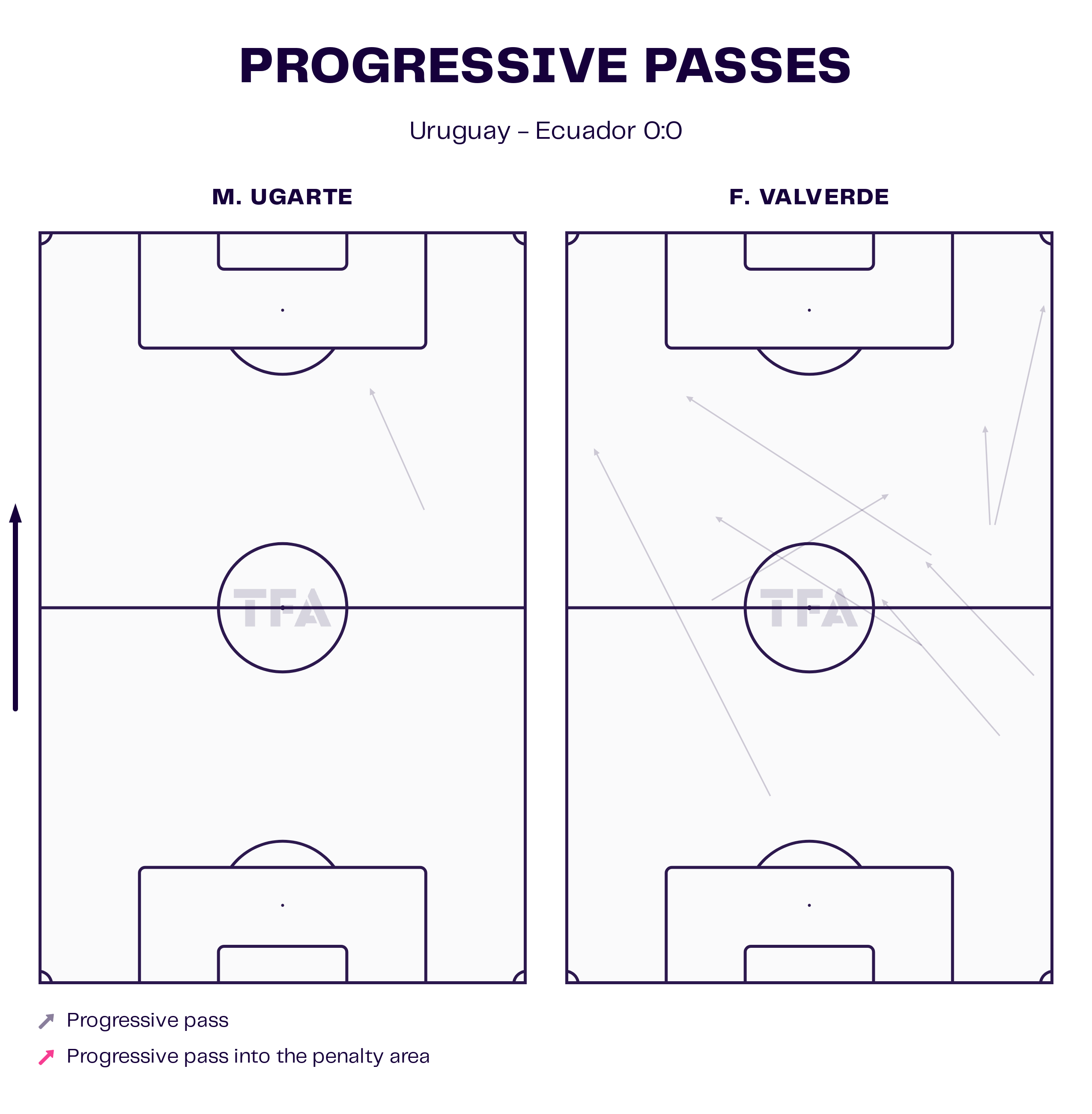

Ugarte understands his limits and does not take risks when sending long balls, as in the image below.

Moments like this one happen frequently.

Bielsa’s team thrives on chaos and intensity in its play; the more long balls delivered to its attackers, the better it performs.

So, what other methods have they been using?

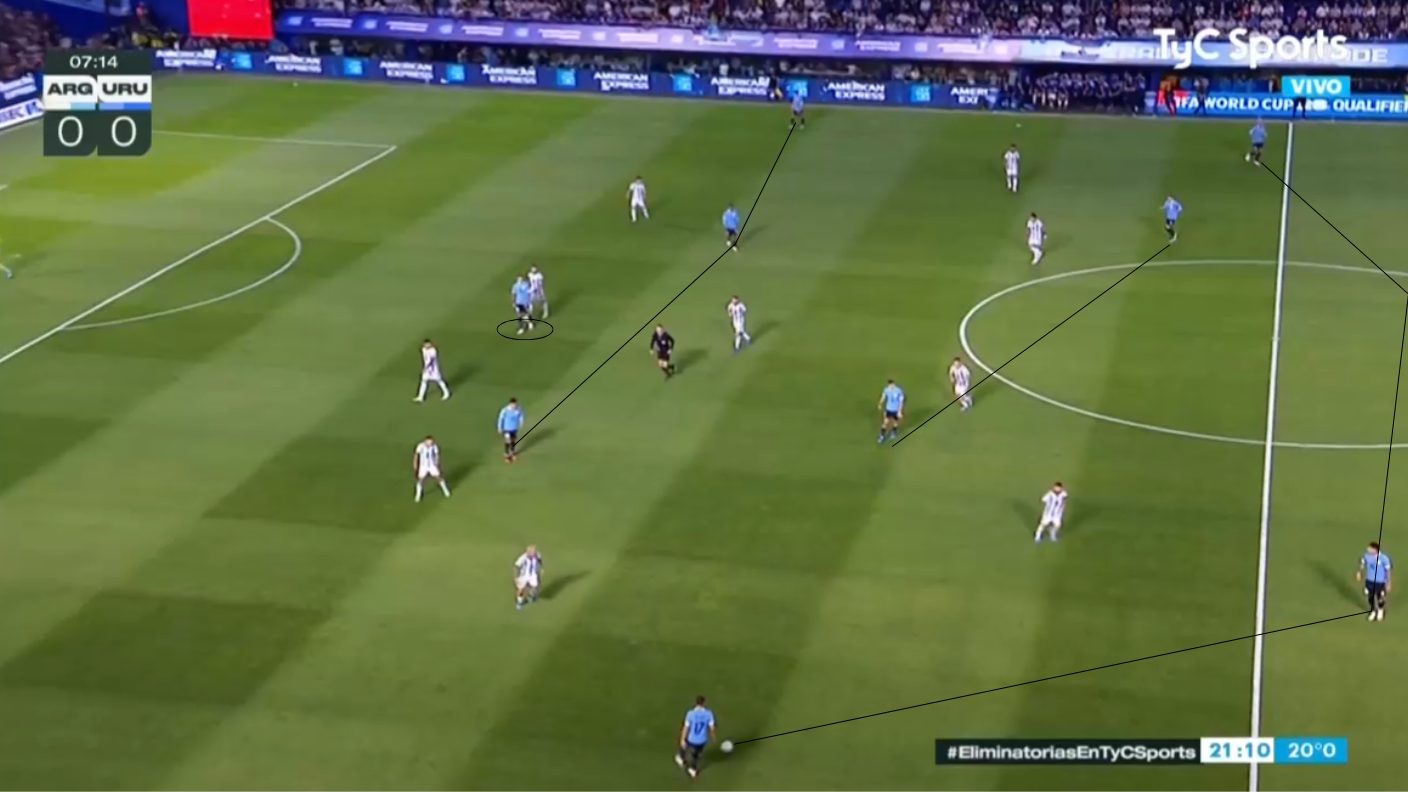

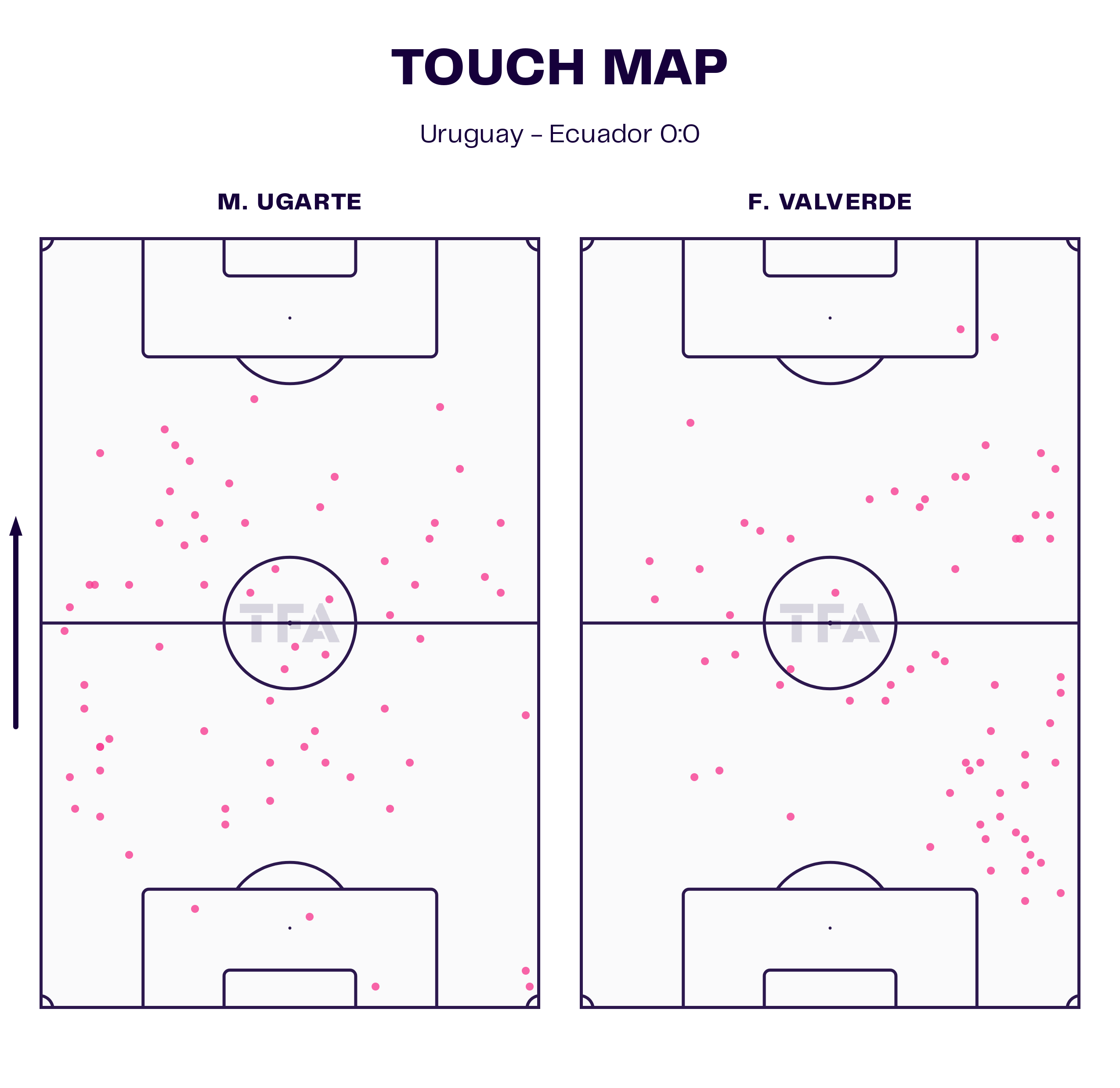

The primary way to hide Ugarte’s limitations in the build-up is by using the second midfielder to create danger from inner channels and deep positions.

Fede Valverde has been very involved in Uruguay’s first passes.

His delivery is cleaner than Ugarte’s, and the range of his passes is insane.

This is not without risk, for sure, but he is capable of pushing the team forward through his carries and passes between the lines or long balls.

As Figure 9 shows, Uruguay allows Valverde to intervene when he detects the possibility of progressing faster.

He does not control the game; his link-up play is purely intuitive and very vertical, but it is what Uruguay’s style of play needs.

The problem is that the times when Ugarte gets the ball with potential danger in behind, he does not exploit it.

Ugarte’s volume of actions with the ball per match and without pressure is more than Valverde’s.

Ugarte tends to receive in central zones facing the goal, and Valverde receives less than him in a shorter influence zone.

But this allows him to send balls to the weak side.

The question is, what is their impact? Their progressive passes answer this.

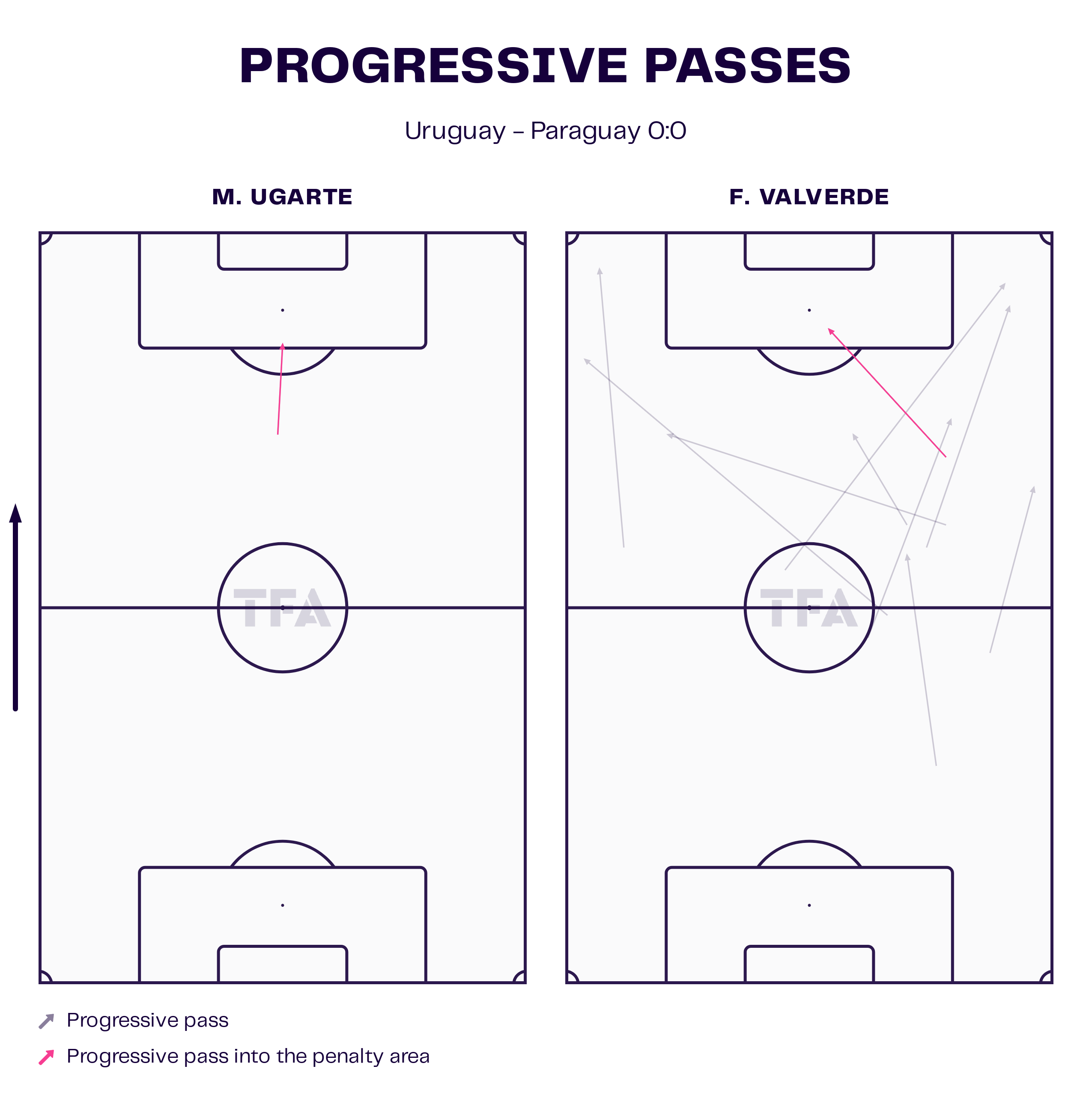

As mentioned, Valverde’s bravery and accuracy in progress make him a valuable resource in possession of Marcelo Bielsa’s Uruguay.

He has a lot of quality with his feet, and he takes risks.

When Valverde is not reading sequences to send risky passes, Ugarte cannot assume the responsibility of the first passer.

As Figure 12 shows, Valverde was not evident in the first passes against Paraguay, but he was a complete virtue in the final third.

The Real Madrid player is a very productive midfielder with the freedom to penetrate the rival’s box and carry the ball in advanced zones.

The necessity of a more technical guy next to Ugarte to push the team forward is inhibiting Uruguay’s best player in terms of quality.

Another Solution Next To Ugarte – Nicolás Fonseca

Of course, Marcelo Bielsa will understand what happens in his build-up structure but is still looking for a solid solution.

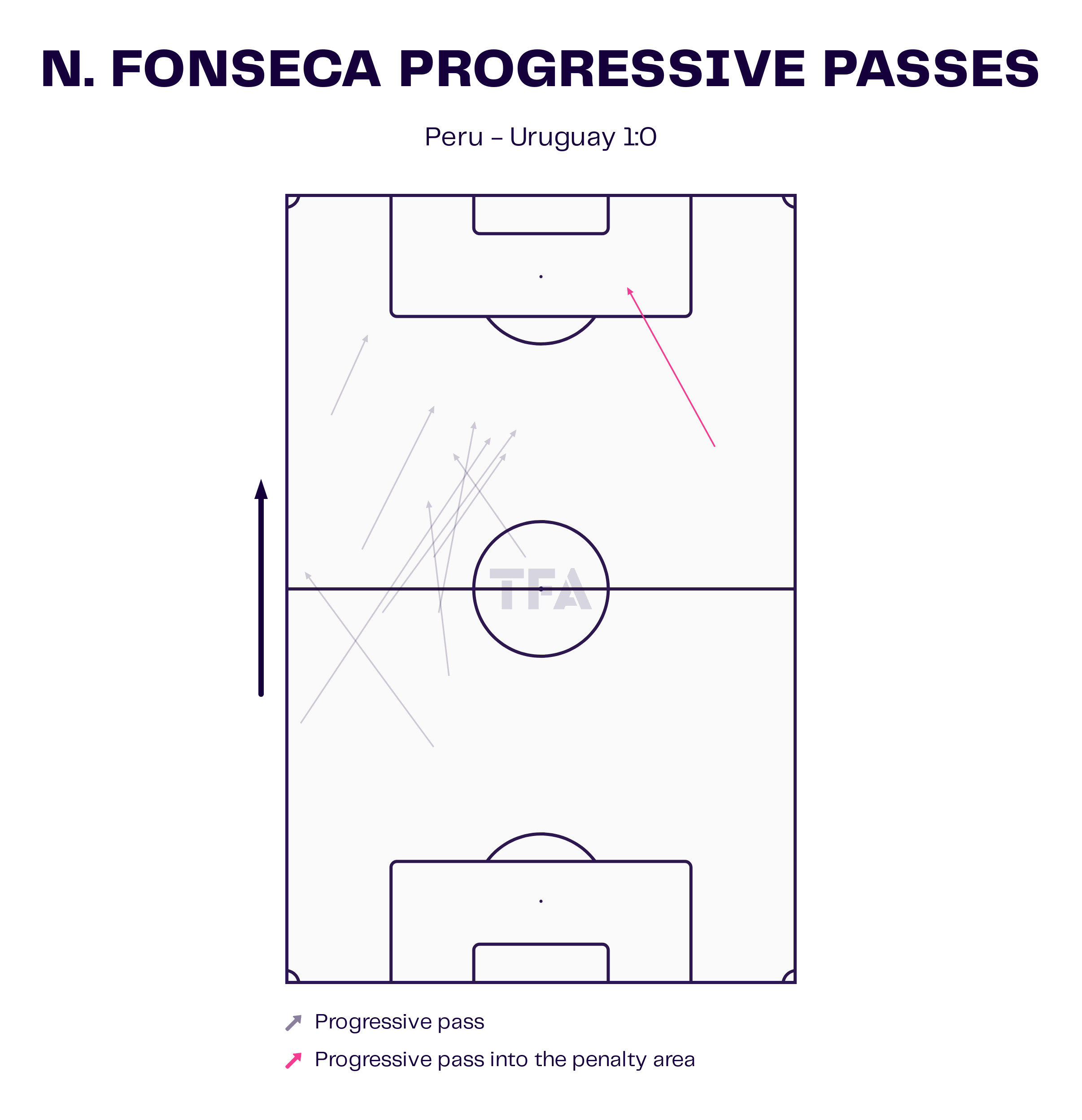

The most exciting experiment was, perhaps, the Nicolás Fonseca start against Peru.

He is a defender midfielder who can push the team forward with his passing ability.

Bielsa used Ugarte as a centre-back in something of a false back-three that day.

In the build-up, Maximiliano Araújo (left wing-back) used to take height on the left, and Nicolás Fonseca positioned himself deeper on that side.

Nicolás Fonseca Progressive Passes Map

Fonseca’s performance against Peru gave massive help to the team in ground passing range.

The only trouble with him is his oriented control.

He could be better at receiving and preparing the following action; sometimes, he delays the possession due to miscontrol.

In Figure 14, Fonseca chose the wrong way to control the ball, taking into account the power of the opponent’s pass.

Once he intercepted, Olivera was offering a run.

However, he was too late to send the pass.

When his control is reasonable, Fonseca is more of a risk-taker and more productive with the ball than Ugarte.

He uses the spaces ahead to carry the ball into and progress.

Also, his passing technique in inner channels, although it generates some losses, is refined.

Conclusion

With the quantity of injuries that Uruguay have suffered, their system has had problems.

Probably, in the peak (so far) of Bielsa’s Uruguay, they were able to have some weaknesses in their build-up and live with that.

Now, problems are developing at the same time as other teams, so Uruguay will need to reinvent itself.

In the short term, the options are few.

If Fonseca is in the XI, Bielsa could give more freedom to Valverde.

Combining Fonseca with Ugarte in a double pivot can help to recover many times before the final line and keep hiding Ugarte’s problems in possession.

Alternatively, he could completely transfer the responsibility of being the first passer to Fonseca.

Then, Ugarte would be a centre-back to defend in open-pitch actions and offer great performances in a build-up in that position — no more back to the goal.

Ugarte can help with the lack of centre-backs after Araújo’s injury, although Santiago Bueno has been great in the last matches.

In the long term, Facundo Bernal (Fluminense, 2003) is potentially the next top Uruguayan defensive midfielder.

He should keep growing and maintaining this development line, but he seems like the best long-term option there — an analysis for another day.

Hopefully, Bielsa will find the best way to boost Uruguay’s national team in one of the most hard-fought qualifiers in recent history.

Comments