For the past few years, the Brazilian league has been dominated by a few elite clubs. A few of these come from Brazil’s traditional 12 big clubs, while others have slowly asserted themselves at the top of Brazil’s food chain, such as Fortaleza and Athletico Paranaense. Nonetheless, the top of the Série A table has been seeing the same familiar faces for a few seasons now.

Occasionally, the less traditional clubs will pop into the spotlight for one reason or another. The most common is obviously young stars going to Europe, with Ituano selling Gabriel Martinelli to Premier League’s Arsenal, for instance.

Cups are another source of light for the less popular clubs, with non-league Água Santa eliminating the likes of Red Bull Bragantino and São Paulo to take on Palmeiras in the final of the Paulista. However, these successes come and go. Sustainable success in ascension to the top of Brazil’s food chain is rare, but it is quietly taking place in Minas Gerais.

After reaching promotion to the Série A in 2021, América Mineiro have established themselves in the first division with back-to-back mid-table finishes. Continentally, the Coelho were surprisingly competitive in last year’s Copa Libertadores, and this season, they have recently defeated South American giants Peñarol 4-1 in the Copa Sudamericana. The Minas club’s ascension is undeniable, and without the typical pressure of a big club, Vagner Mancini is slowly building an exciting project at the Arena Independência.

The results are merely a reward for the organisation introduced by Mancini. Tactically, the Brazilian manager has introduced a fluid structure in possession guided by clear principles, and out of possession, América are aggressive and disciplined.

The system has certainly fostered individual success. Martín Benítez has found a home after displaying flashes of brilliance at Vasco da Gama, São Paulo, and Grêmio. After being called up to Brazil’s national team, 20-year-old right-back Arthur has earned a summer transfer to Bundesliga’s Bayer Leverkusen.

This tactical analysis will provide an in-depth breakdown of Vagner Mancini’s tactics at América Mineiro, identifying how the Brazilian manager has been guiding the Coelho to the top. In and out of possession, this analysis will outline the guiding ideas behind América’s recent success.

Structure

While América Mineiro are far from a possession-based side, with 47.84% average possession this year, they certainly look to construct organised and intentional attacks. They are generally more vertical in their passing behaviour, with 12.93% of their passes being long passes. At any rate, before exploring the guiding principles in their progression, breaking down the structure provides the necessary context.

While the structure is extremely fluid and at times emergent (non-imposed) based on spontaneous developments, there is a relevant guiding organisation in possession. This organisation begins in an expansive 4-3-3 shape, looking to maximise the playing area. Despite initially holding maximum width, the organisation’s structure is very fluid and dynamic in its development.

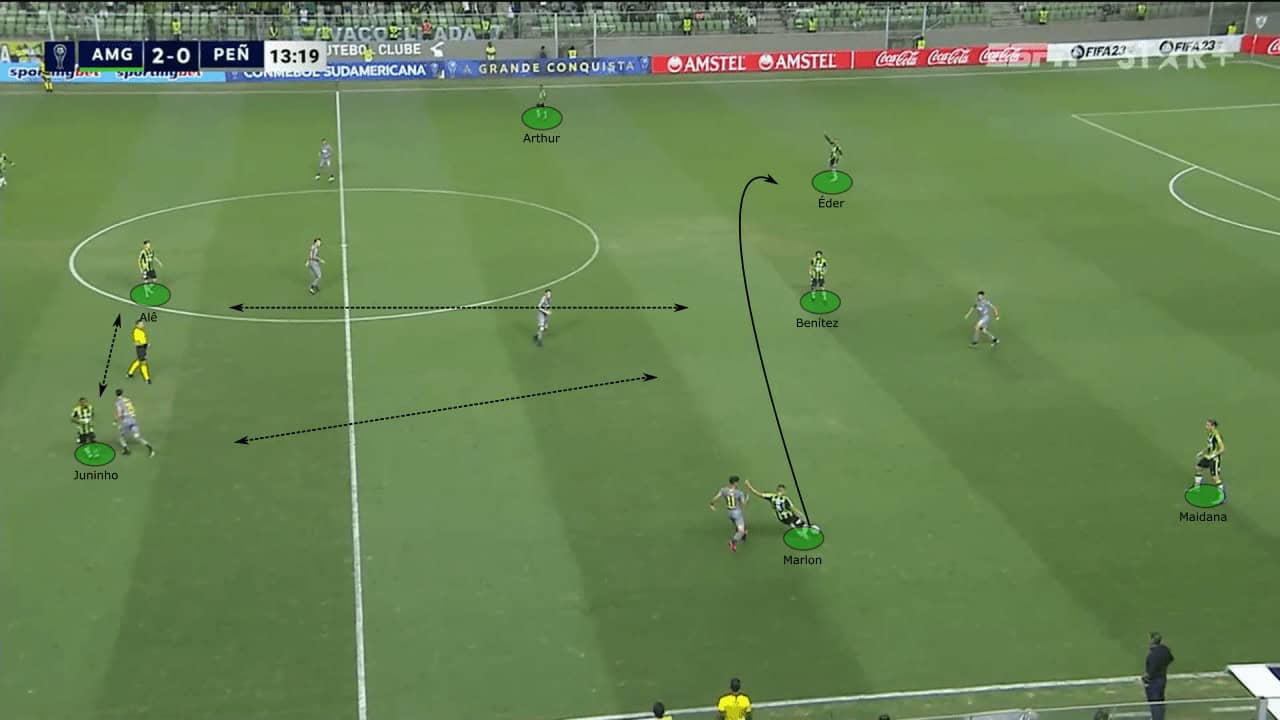

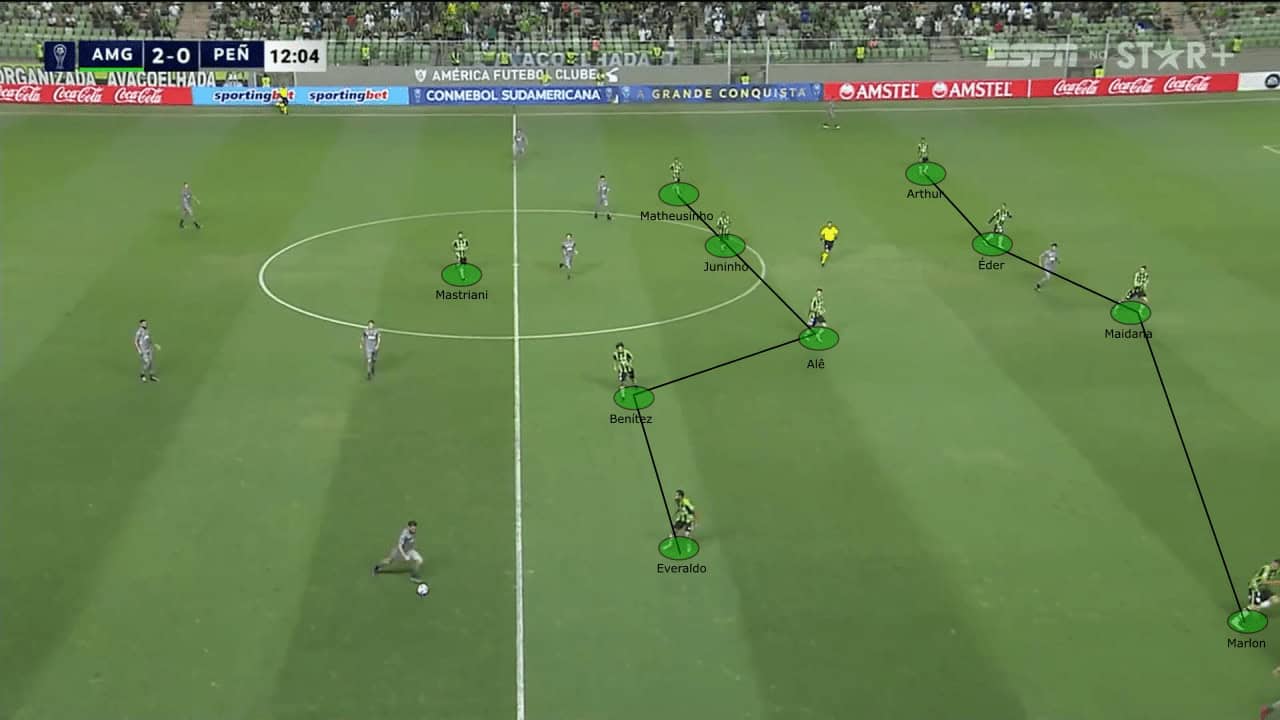

The image below outlines their 4-3-3 shape, identifying the names of the players in order for clarity throughout the analysis. The midfield trio has Benítez and Juninho sitting ahead of Alê, albeit they tend to rotate a lot like in the example below. With their stretched nature, they are able to easily switch the ball and circulate possession from side to side.

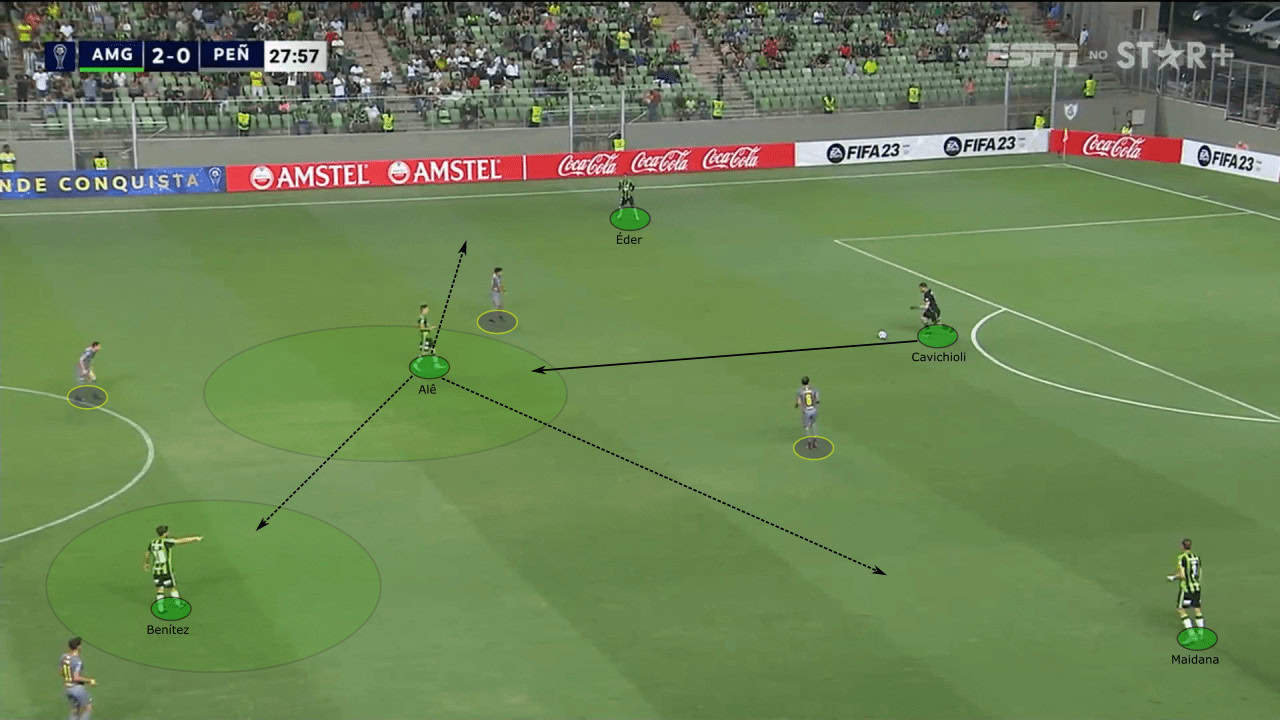

Directing possession to the wide areas, they are able to create effective structures from their initial organisation. In the example below, the centre-back drives the ball forward in the wide channel. The winger and the nearest midfielder, Matheusinho and Alê respectively, provide support from the half-spaces, creating diagonal angles to the fullback and the centre-back. Once the centre-back plays it inside to Alê, Arthur, the right-back, makes an overlapping run to continue the ball progression.

Now on the left side, we can identify similar patterns in the structure. In this specific instance, the winger, Azevedo, now begins in the same channel as the fullback. The midfielders Alê and Benítez are the ones to provide support from the half-space. Although through different positions, they create a similar structure in the wide area.

With the playing area stretched, the midfielders are able to find gaps between the lines more easily. Alê is usually the deepest-lying midfielder, providing an immediate option to the centre-backs behind the first line of pressure. Benítez and Juninho work together to find spaces further up the pitch, either for more vertical options or to support Alê.

Mancini’s tactics are carried out in a very simple 4-3-3 organisation. This organisation is expanded throughout the pitch with initial maximum width, where the midfielders can find gaps inside or support the wide players. This linear and rather easy structure initially makes for a more clear progression, with bigger spaces and more identifiable positions. However, as progression advances, the structure becomes much more fluid and dynamic.

Fluid progression

Using the structure as a reference, we can identify a few patterns and methods of progression explored by América. As mentioned, the structure is very fluid, and this helps make progression more direct with spaces opening up more frequently. The fluidity begins from their initial positional references, so a few patterns emerge more consistently.

Perhaps the most obvious one is the midfield trio. Despite Alê starting deeper than the other two, they can interchange positions quite easily. In the instance below, Juninho has the ball in the position that Alê usually occupies, so Alê moves forward in a more advanced space. This preserves balance throughout the midfield and keeps the opposition stretched.

With Benítez ahead of Alê in the right half-space, Aloísio, the centre-forward, drops into the gap left in the midfield. As possession develops, players naturally get dragged into other spaces and positions. Mancini’s men do a great job of finding the spaces left behind and maintaining constant movement throughout the structure. The initial positional references are rather loose, without the need for players to immediately return to their point of origin.

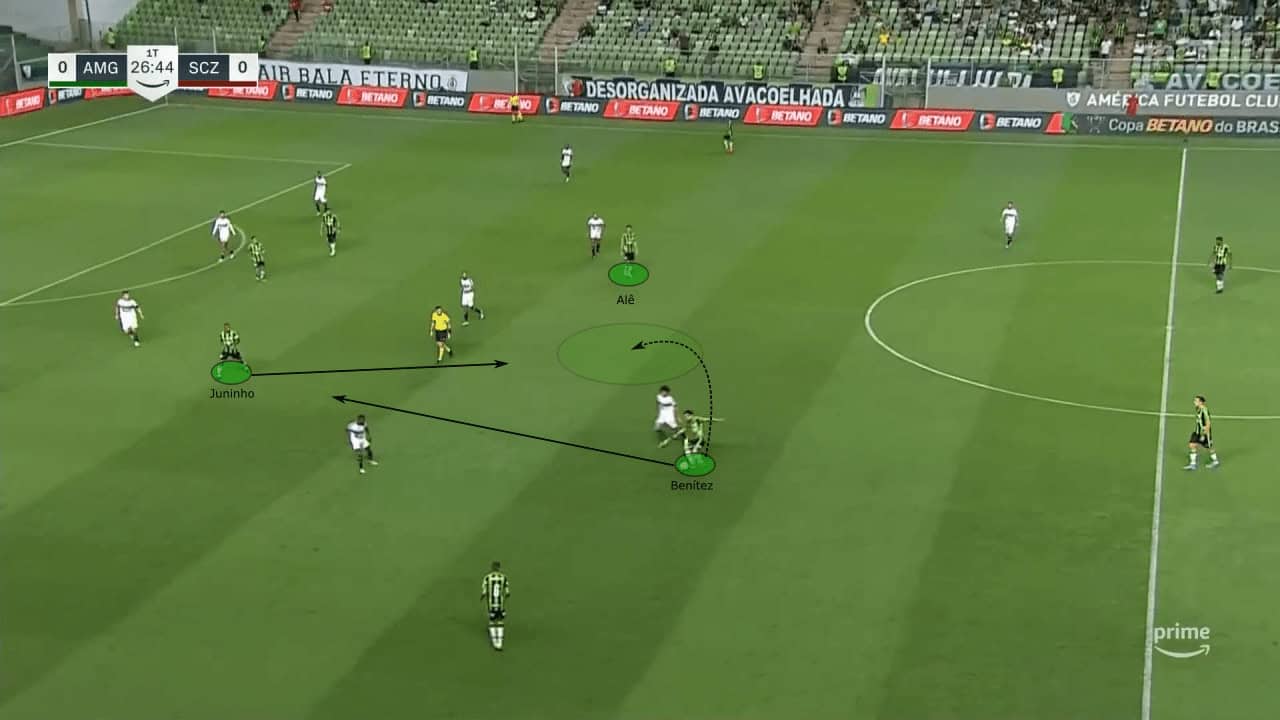

The segment below serves to further illustrate the midfield’s behaviour. In this instance, the players are once again occupying different positions while still maintaining a similar organisation. Benítez begins deeper with the ball and finds Juninho, advanced in between the lines. After playing the pass, Benítez moves to receive it back from Juninho.

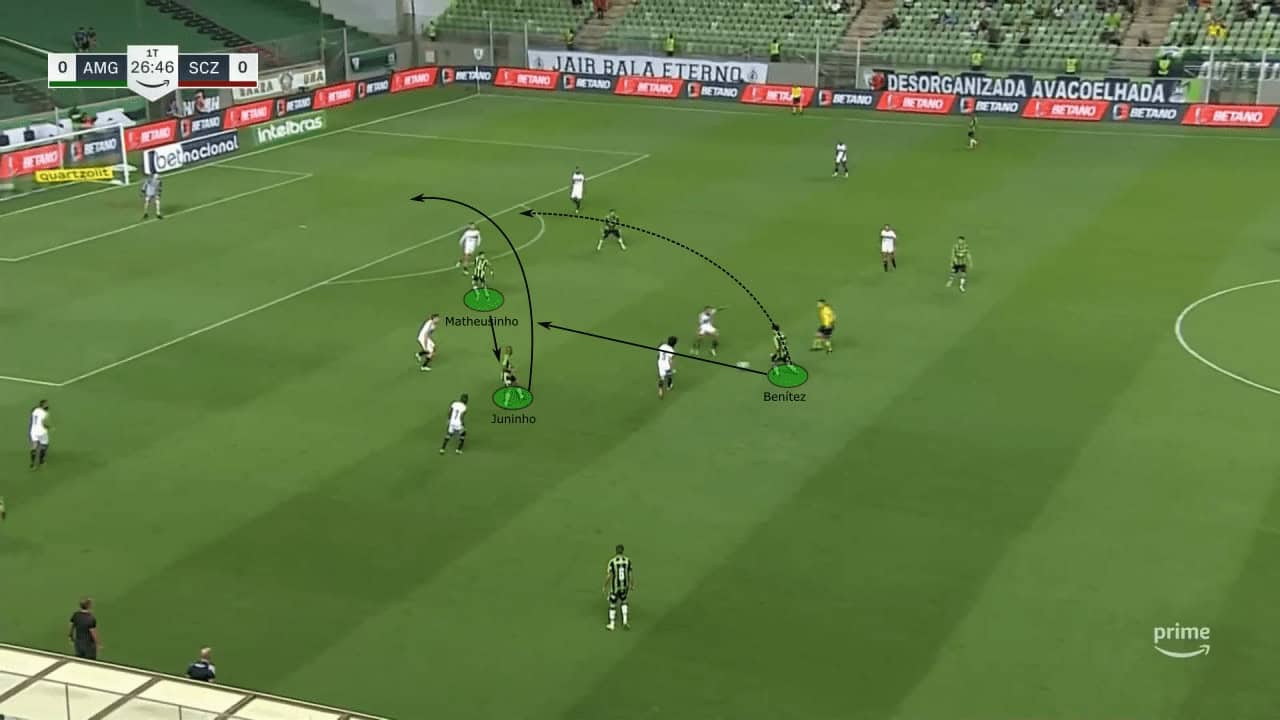

After receiving it back, Benítez plays another vertical pass, this time to Matheusinho. Matheusinho is the right winger, but in this case, he has drifted far into the central channels. Matheusinho plays Juninho, who finds a lob to Benítez in the box. The fluid movement of the midfield in this segment, both from their initial position to how the play develops, serves to illustrate a key pattern in their progression.

In fact, the midfielders are very aggressive in their positioning. Especially Benítez, they can make runs into the channels and create overloads against the opposition’s backline. In the example below, Benítez makes a run from the midfield into the final third behind the backline.

In this specific case, the winger remains in the wide channel while the central midfielder pushes up into the half-space. This is specific to how this play has developed. At other times, they can come inside to the half-spaces while the fullbacks occupy the wide channels, or vice-versa. The development of the organisation is very spontaneous; however, it is guided by some clear ideas.

Continuing with the wide dynamics, we can observe more in-depth the behaviour of the wide players. While América initially resort to maximum width, as identified earlier, they also use minimum width, with the wide player coming just into the half-space.

In the instance below, the typical line of five attackers is there, with the two wingers, the two central midfielders, and the centre-forward. However, the wingers are significantly more narrow, with Azevedo even making a run into the central channel. This run occupies the right-back, and once Alê finds Aloísio, he is able to instantly play Benítez free in front of the goal.

The wingers making inverted runs into the central channels is actually very common in Mancini’s tactics. Below, right-back Arthur is in the half-space, and he plays a cross for Azevedo making a run into the box. The wide players, as identified below, frequently come inside from an initial wide position to overload the central areas.

However, it is relative, as is everything in Mancini’s tactics. There are multiple alternatives to progression, all building on the initial organisation. While at times the wide players can come inside to create minimum width, they can also hug the touchline to stretch the defensive lines.

In the example below, Matheusinho is holding maximum width on the right while Arthur provides support in a more central lane. With Arthur coming up, he and Benítez create a 2v1 against Santa Cruz’s defender. Benítez makes a run in behind to drag the defender and create space for Arthur to receive the ball.

Mancini’s tactics in possession are very well-developed. Starting from an initial 4-3-3 organisation with clear structural tendencies, América have numerous methods of progression. These various alternatives highlight the fluid and flexible nature of their attack, which is guided by clear principles and ideas.

Hiding the third man

Defensively, América are aggressive and disciplined. With so many dangerous teams in the Brazilian elite, it is unlike for clubs with less investment to be so aggressive. Nonetheless, Mancini has constructed an extremely organised and disciplined defensive system. With a PPDA of 7.84 and 0.86 goals conceded per 90 this year, it is proving rather effective.

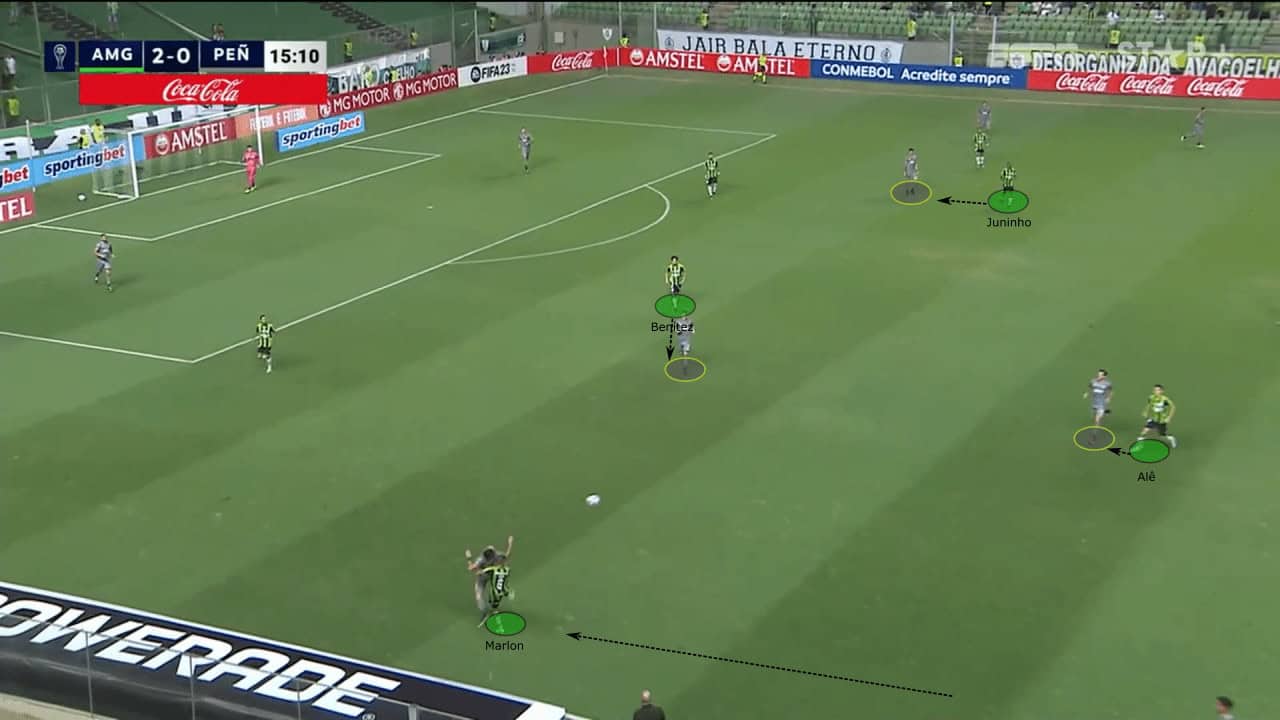

Against most sides, América look to press high with a very aggressive organisation. We can use their press against Peñarol to illustrate their organisation. In the midfield, Mancini’s trio man-marked Peñarol’s midfielders. Leading the line, centre-forward Gonzalo Mastriani began on the right while left-winger Everaldo came forward. This allowed them to go 2v2 against the centre-backs.

Everaldo looked to press the centre-back from a wide angle, blocking the passing lane to the fullback. This was an attempt to ‘hide’ the opposition’s extra man. Obviously, the possibility of playing it in the air to the fullback was still there.

Peñarol tried this, but going aerially allowed Marlon, the left-back, the time to push up and challenge the ball. This meant Marlon left his respective winger alone, so the nearest centre-back stepped up to cover.

Looking to leave an extra man to cover in the backline, América naturally have a man down in their press. They looked to hide this with Everaldo’s pressing angle, and when Peñarol tried to overcome this, a domino effect in América’s backline began. It is certainly a riskier approach, but Mancini’s men are extremely disciplined and coordinated in their defensive behaviour.

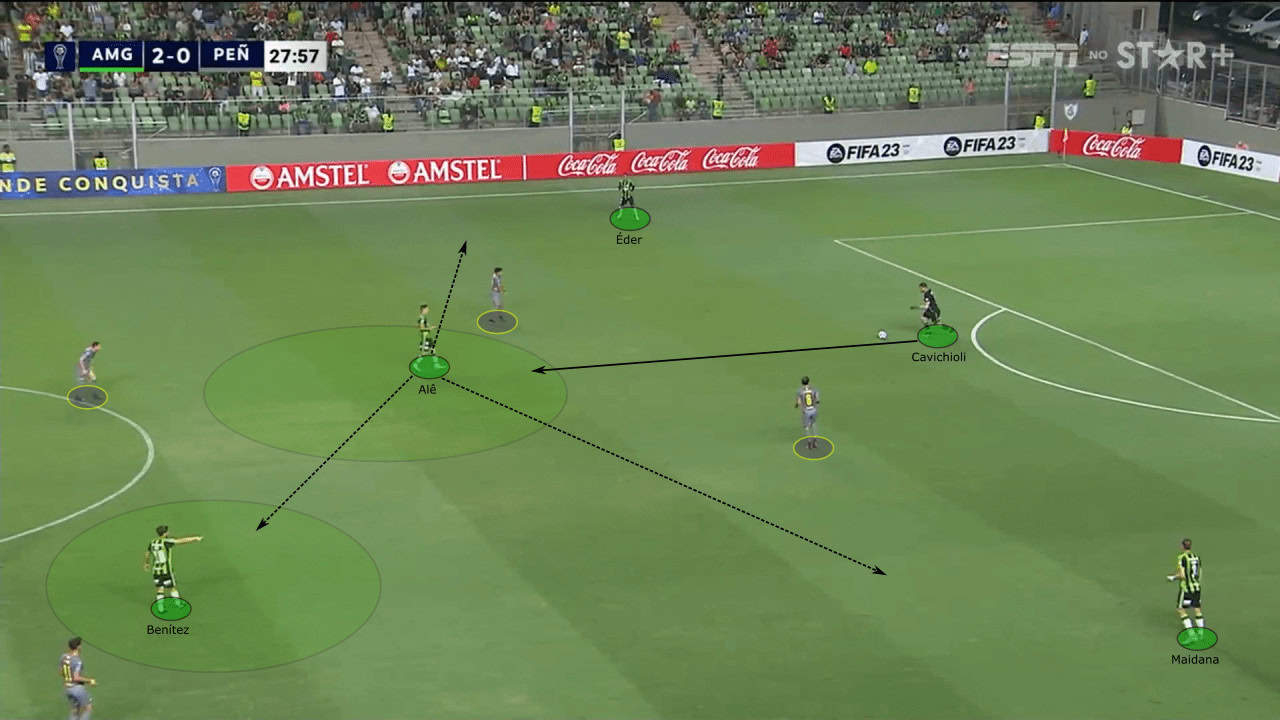

In a mid-block, Benítez tends to jump forward to pressure the centre-back at times. This forms a 4-2-4 shape and leaves them outnumbered in the midfield. Consequently, it is done only in specific scenarios and with cover from the centre-backs to pick up the extra man should he be found.

Otherwise, their mid-block is organised in a compact 4-5-1 organisation. Moving as a unit allows for the wingers to protect the central areas and eliminate passing lanes for the opposition to progress. Additionally, with a line of five, they are quick to create numerical superiority on the ball and congest the playing area.

This can be seen more significantly in the wide areas, like in the example below. As Peñarol try to progress through the left side, Matheusinho and Arthur provide immediate protection. Juninho is able to join them, while Alê and Éder provide cover. This creates a 5v3 in the wide channels and effectively protects the opposition from advancing into their own third.

Conclusion

Vagner Mancini is building an extremely organised project with América Mineiro, slowly taking them to the top of Brazil’s food chain. Only reaching promotion to the first division two seasons ago, the Coelho are now comfortably settled in the Série A with some exciting performances in continental tournaments.

They are off to a fantastic start in 2023, but it will be interesting to follow América’s progression in this year’s Série A.

Comments