The last decade for Valencia has been truly tumultuous, to say the least. At the turn of the millennium, the club was without a doubt one of the most prominent clubs in Spain, with Valencia managing to win two titles, a UEFA Cup and a UEFA Super Cup between 1999 and 2004. Within this period, the club were also able to reach two UEFA Champions League Finals.

However, the years following 2004 proved to be less fruitful for the side and with less success, a few signs of instability began to appear. One of the most significant signs of this instability was the revolving doors of managerial appointments, with a young Unai Emery and Ronald Koeman all having stints at the club, as well as a few other interim managerial appointments. Amidst all of this, the side still had many talented players on their books, with the likes of David Villa, Juan Mata and David Silva helping the club secure a Champions League spot in the 2009/10 season.

Although having several talented players, the club was forced to administer outgoings to balance their books, with David Villa sold to Barcelona and David Silva sold to Manchester City. In the resulting three years after these exits, Valencia still remained competitive, finishing third twice as well as fifth. However, the issues around the debt incurred by the club were still persistent, with the club facing administration in 2014.

In August of the same year, Peter Lim purchased 70.4% of the club’s shares and subsequently became the owner of the club after negotiations with the creditors of the club. Nuno Espírito Santo was trusted with the managerial responsibilities and, in his first season, managed to guide the side back into the Champions League places after a two-year absence. After an exodus of talent, the club made a notable attempt to improve the strength of the side with players such as Álvaro Negredo and André Gomes brought in by the club.

Although starting off brightly, Espírito Santo could not maintain the same form the following season and had a poor start to the 2015/16 La Liga season, resulting in his dismissal. The following years consisted of another spell of Valencia’s personal managerial merry-go-round with several managers entrusted with the head coach responsibilities at the club. As a result of this, Valencia’s on-pitch performances struggled, and questions were beginning to be asked about Peter Lim’s ownership.

In 2017, the club turned a new corner with the appointment of Marcelino García, who managed to guide the club to successive top-four finishes as well as a Copa Del Rey.

Nevertheless, with fans firmly against Peter Lim and Marcelino publicly showing his disgruntlement towards the ownership, Marcelino was sacked by the club. Once again, the situation around the club’s financial stability began to rear its head again, with the club forced to sell key players such as Dani Parejo, Rodrigo and youngster Ferran Torres, all for below-value transfer fees. Four years on from Marcelino’s departure and the wedge between ownership and the fans the largest it has ever been, Rubén Baraja, who played for the club as a midfielder in their successful years in the early 2000s, was appointed by the club at the start of 2023, with Valencia floating dangerously close to the relegation zone.

This scout report will provide a tactical analysis of How Baraja looked to solve the tactical issues that plagued the side last season, as well as take a look at the tactics being deployed in the side at the start of this season.

2022/23 Problems in attack and defence.

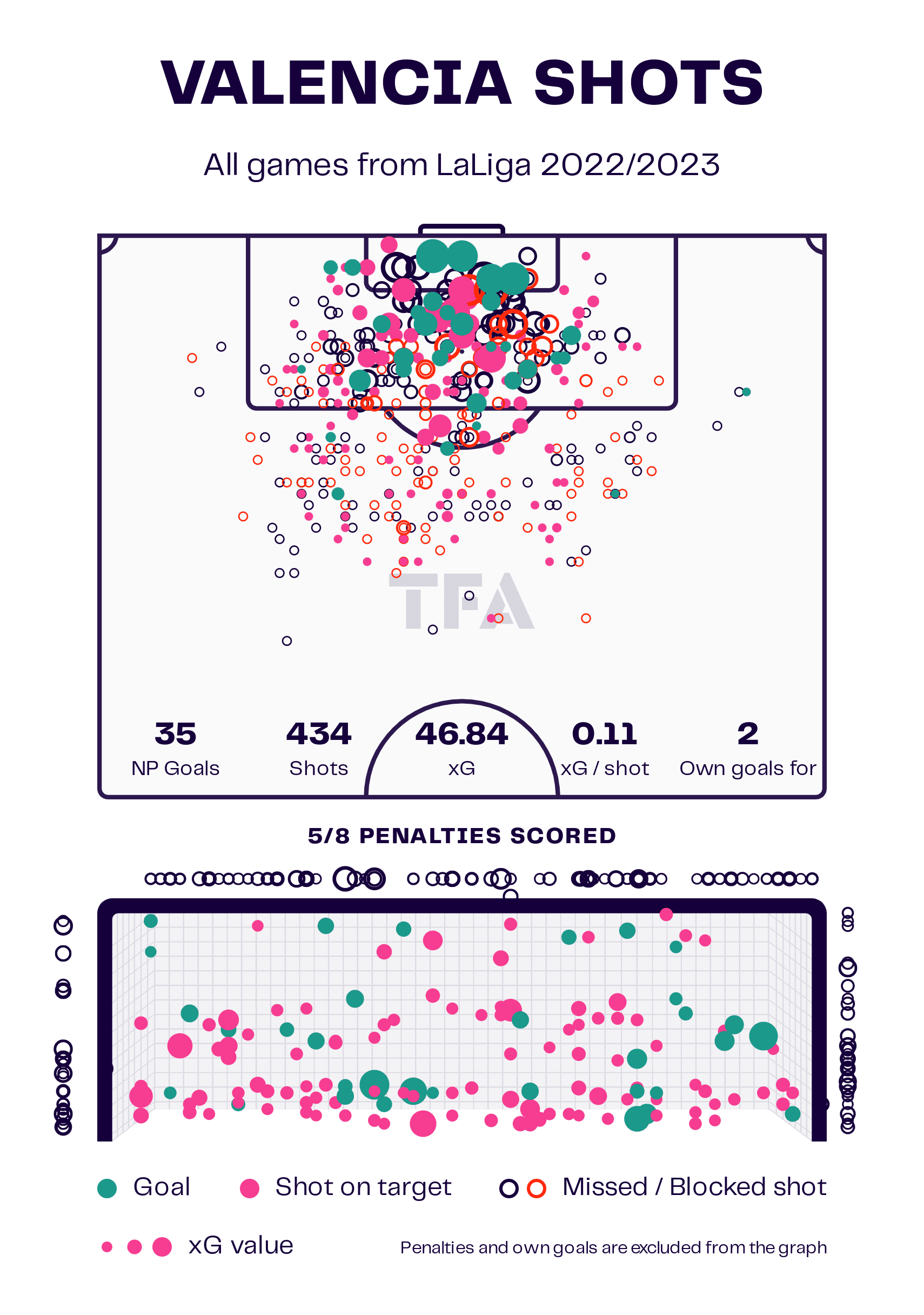

When examining their underlying numbers, it is clear that Valencia’s attacking output is not the most significant cause of their 16th-placed finish last campaign, with the side scoring the 12th most goals in the division with 42 in total. When looking at their goal figures from an xG perspective, the side underperformed by 11 goals, which, considering the xG totals of other sides in the division, would have been the ninth-best goal tally in the league. This suggests that the side did not necessarily struggle to create chances last campaign but instead struggled to put them away.

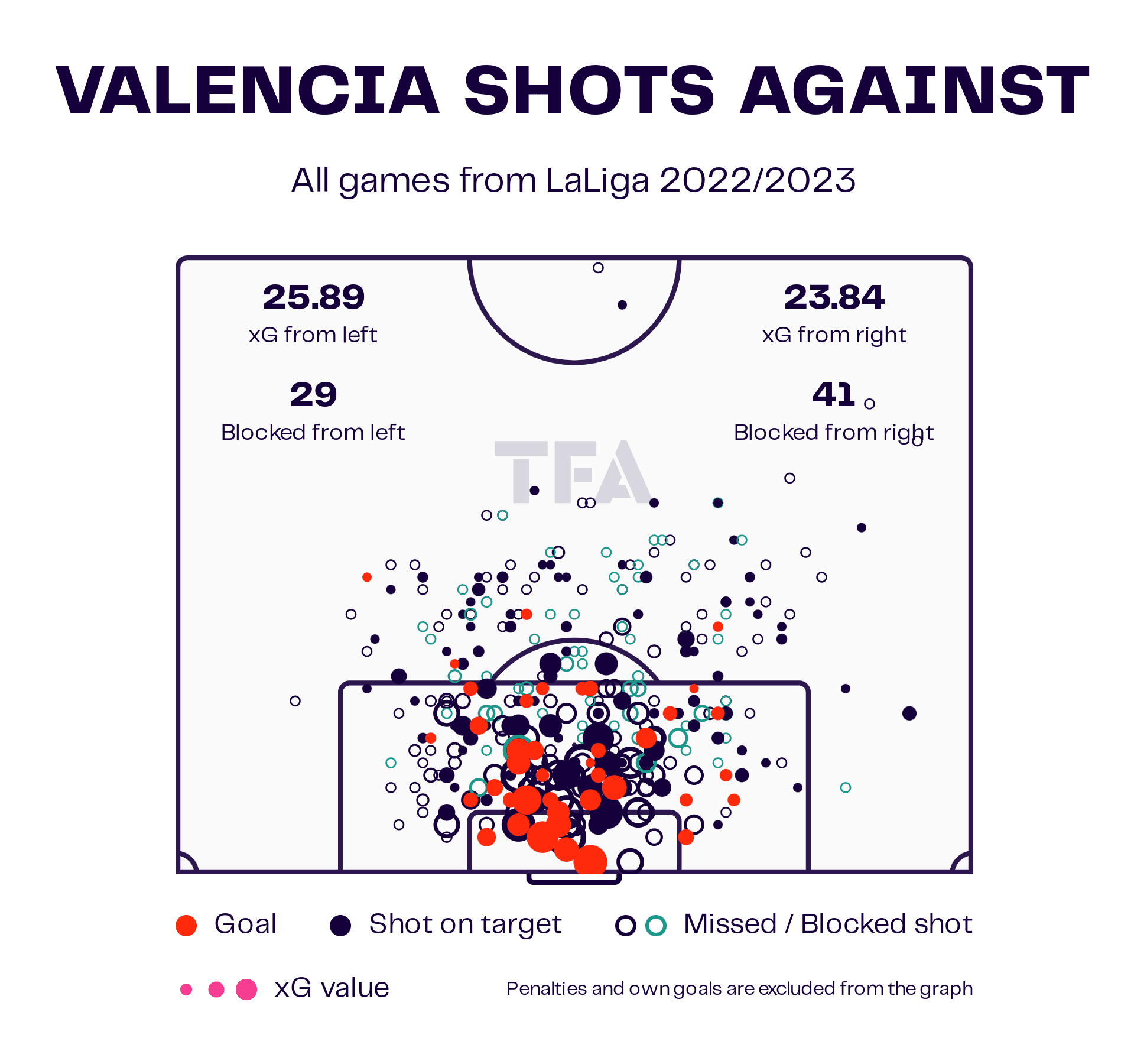

From a defensive perspective, almost the opposite can be said. However, the side’s record of 45 goals conceded was the 12th-best in the league; the side overperformed by seven goals in this metric. However, their xGA tally was still the 11th-best in the league. Overall, the underlying numbers suggest that Valencia were relatively unlucky to finish 2 points above the relegation zone. It would not be outlandish to suggest that the internal turmoil, boardroom level, as well as the discontent of fans played some part in the side’s woeful campaign last season.

Rubén Baraja steadies the ship.

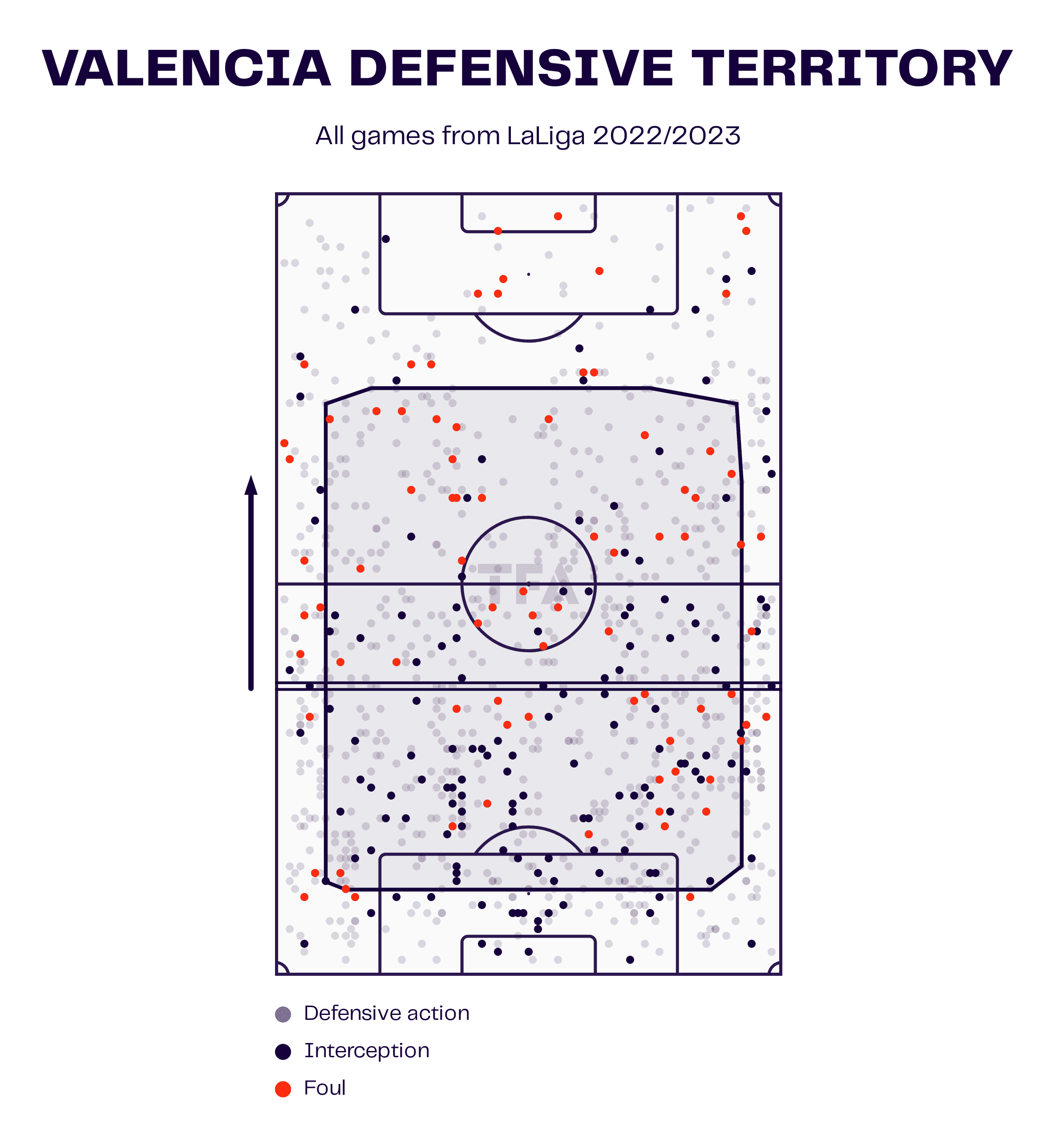

When coming into the club, Ruben Baraja clearly stated that the side needed to improve defensively. From analysing Valencia towards the end of last season and this season, it is clear that the side have looked to ensure defensive security before working in detail on the attacking aspects of their game model. Although the side were, on average, defensively positioned relatively high up the pitch, as the image below suggests, the side was not highly aggressive in their attempts to win back possession.

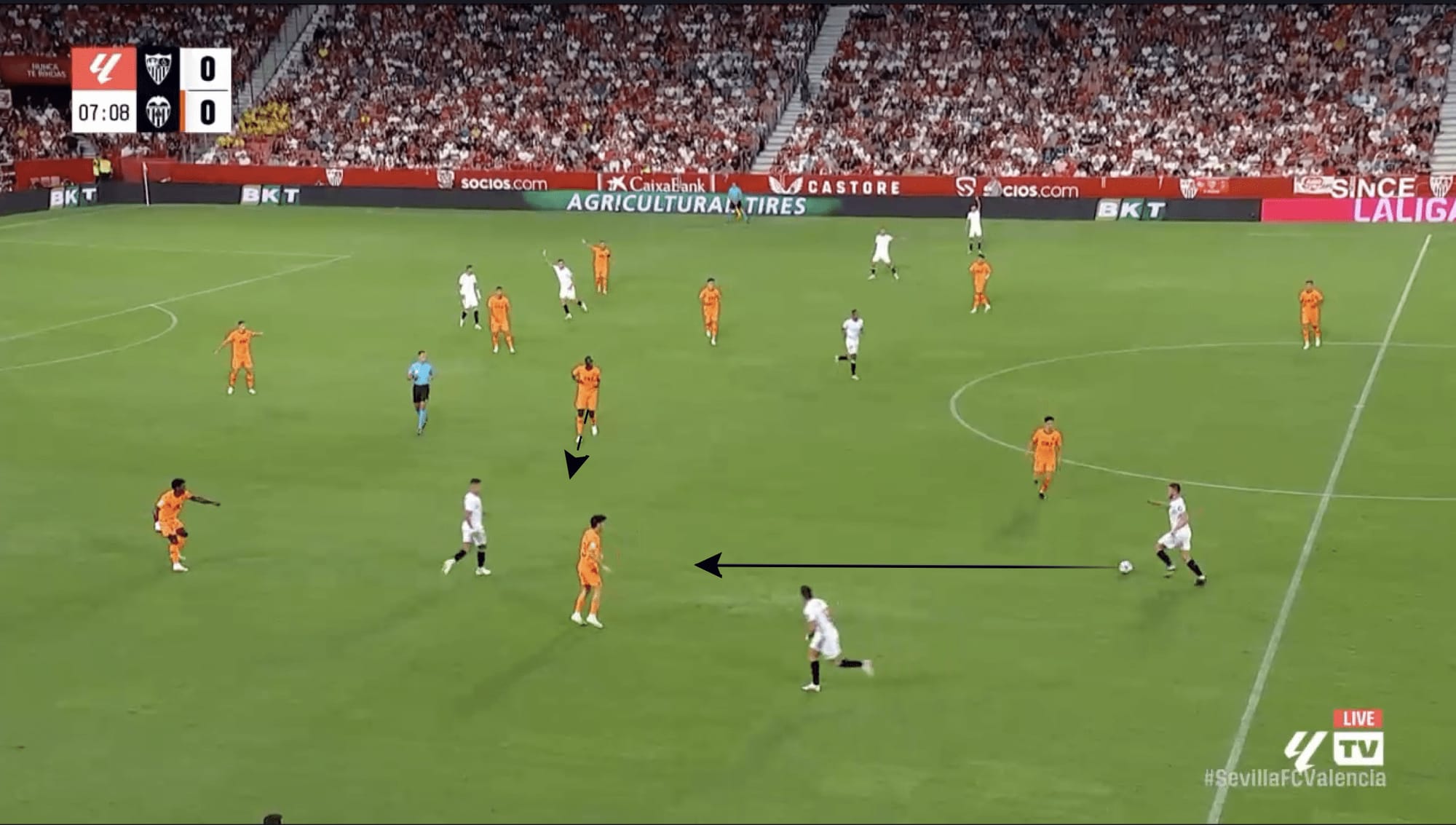

Valencia, under Baraja, have looked to defend in a 4-4-2 or 4-1-4-1/4-5-1. An example of their 4-4-2 formation can be seen in the image below. Over the second half of last season, the side have focused on denying passes to the opposition midfielder, looking to force the opposition to play down the channels.

A common weakness with 4-4-2’s is that due to the flatness of the formation, at times, it can be easy for the opposition to find players who are looking to receive the ball between the lines. However, when watching Valencia, it is very apparent that the players are well aware of protecting potential passing lines that the opposition may look to exploit.

As seen in the image below, Javi Guerra, the midfielder, adjusts his body shape to allow him to challenge for any passes played between him and Samuel Lino. In addition to this, José Gaya is also positioned to challenge the opposition player between the midfield and defensive line.

What is also apparent is the close distance between Andre Almeida and Justin Kluivert, allowing them to shift and cover the defensive midfielder as well as protect passes through the centre.

With the midfield able to protect passing lanes between them and receive support from players behind them, it is difficult to break down Valencia in the wide areas without committing several players to these zones. With four players across the midfield and good protection of passing lanes, the side can adequately defend one side of the pitch and be able to defend switches in play by the opposition.

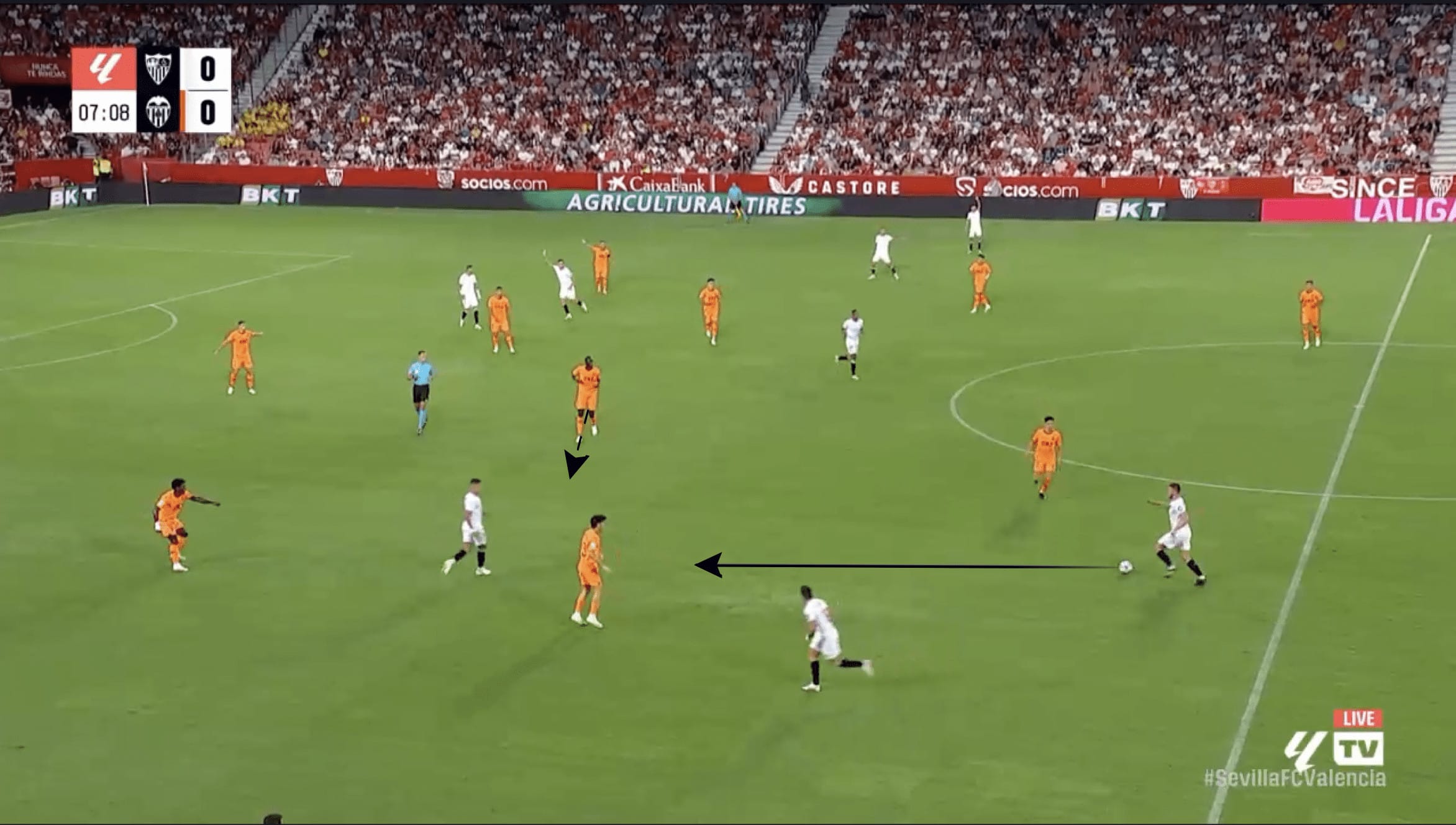

This can be seen in the image below after the opposition right-back plays a pass to the left centre-back. As a result of this, Valencia’s structure takes on a similar form to that of the previous example, with Nicolas González shifting to his right in order to reduce the space between him and Diego Lopez. Additionally, Dimitri Foulquier offers cover between them, similar to the cover provided by Gaya on the opposite side.

Although there are no glaring issues in the side’s defensive structures, in certain situations last season, it was apparent that a few players struggled with the timing and angle of pressure. This can be seen in the example below: Justin Kluivert pressing the opposition full-back with a rounded run.

With this sort of angled run, as well as his flat body shape, Kluivert becomes relatively easy to beat in 1V1 situations and creates space for the player to attack, as seen in the image below. As a result, the opposition full-back can engage both Kluivert and Almeida, which frees up a passing option to another player and allows the side to progress the ball down the wing.

On the left-hand side, Lino was also guilty of occasionally pressing with this type of run, which had the same resulting effect as the previous example. This can be seen in the image below, with Lino pressing at an angle that blocks access to the touchline but opens up space in the middle of the centre. Although there is a 3v3 in this area, Lino’s pressing action has allowed the opposition to gain a positional advantage.

Valencia’s first two matches have strongly suggested that they do not intend to stray too far away from their structure and principles from the second half of the previous season. Generally, the defensive security of the side has remained as stable as it was under Baraja in the last campaign. However, this season, Mouctar Diakhaby has played as a central midfielder, not a centre-back.

This has harmed the side in the attacking phase of the game in regard to ball retention, but it has also caused a couple of weaknesses defensively. As mentioned earlier in this piece, Valencia’s midfielders were especially adept at defending the gaps between them to narrow passing lanes and prevent passes to players behind the line. However, Diakhaby has often appeared heavy-footed in shifting across in time to prevent these passes. This can be seen in the example below.

Valencia in attack

At times, throughout last season and at the start of this season, it is clear that Valencia is less refined in possession than they are defensively. This can be seen in the first stages of build-up, with the distances between players sub-optimal at times and an inadequate occupation of specific spaces that would aid the side in progressing the ball.

One aspect that worked to the side’s detriment last season was that wingers were always running towards their own goal to receive the ball, which resulted in difficulty receiving passes. This can be seen in the example below, with Justin Kluivert running towards his goal to receive the ball with an opposition defender behind him. An additional issue in this particular context is the failure of Almeida to move further towards the wide area and offer a passing option to Diakhaby as well as a potential passing option for Thierry Correia, the right-back.

Towards the end of last season, the side began to utilise a back 3 in the build-up. However, structural issues meant that the side still failed to find angles and connections that would allow them to progress the ball. This can be seen in the image below, with the left winger once again in a position where they are running towards their own goal to receive the ball as the fact that there is no player present in the half-space to offer any meaningful support if the player were to receive the ball. As a result, the sides have generally been unable to impose themselves on teams and dominate possession.

Before implementing their attacking identity, many managers have stated that their first port of call is to ensure their side’s defensive security. Although the side faces a few positional and structural issues in possession, this has not prevented them from finding solutions to create goal-scoring opportunities.

One aspect of the side that Baraja has looked to capitalise on is the relative youthfulness of the side, with their attacking 4 having an average age of 21.7 years old. Although this may be alarming regarding experience, Valencia’s forwards are relatively quick and willing to chase long balls played into the space ahead.

This can be seen in the image below, with López looking to run onto a pass from the centre-back Cenk Özkacar.

Conclusion

Valencia’s position in the league at the end of last season was not necessarily an accurate representation of how the side had performed. With a massive underperformance in front of goal and a defensive record amongst the top 12 sides in the league, Valencia may have been slightly unlucky last campaign.

Under Baraja, as this analysis has explained, the side have been able to regain defensive stability. Although still lacking potency in an attacking sense, there are signs that this season will not be as disastrous as the last. However, with the issues around the ownership still lingering in the background, like many of his predecessors, Baraja may have many more hurdles to overcome.

Comments