CA Vélez Sarsfield is one of the biggest names in Argentine football.

The club has won 10 national championships and multiple other titles.

In 1994, they even won the Copa Libertadores and went on to become Club World Champion that year.

After a bit of drought to start the early 2000s, the club hired Ricardo Gareca as their new manager in 2009, a former player of the club in the 90s, and went on to win five titles in five years up until 2014.

Later in the 2010s, the club had a very successful time under former Real Madrid and PSG defender Gabriel Heinze but did not manage to add more silverware to their trophy cabinet.

The start of the 2020s has also not been kind to the club.

Since former Valencia and Southampton manager Mauricio Pellegrino left the club in 2022, it has spiralled out of control.

The last two years have been especially bad for the club, in which they finished 26th and 25th in the 28-team Liga Profesional in Argentina.

While the club is known for its academy, these harsh years with a lot of turmoil have turned a lot of young players away from Estadio José Amalfitani.

Over the last couple of years, Vélez have lost players like Thiago Almada, Máximo Perrone, and Lucas Robertone because different clubs provided them with more attractive opportunities.

Just before this season, Vélez lost more talented academy graduates in Santiago Castro (to FC Bologna), Gianluca Prestianni (to Benfica Lisbon) and Francisco Ortega (to Olympiakos).

After the unsuccessful years and financial struggles, the club could not replace those departures, spending only a fraction of the money they made with those players.

But Vélez Sarsfield made one key signing this winter, Gustavo Quinteros, which changed the club’s trajectory for this year.

The Argentine-born Bolivian Coach came straight from Chile and Colo-Colo after winning multiple titles.

Quinteros brought life into a dead team.

After scoring only 24 goals in 27 games of the Liga Profesional last season, Quinteros’ men have scored 27 goals in just 14 games so far this season.

They reached the final of the Copa de la Liga and are currently leading the league for the first time in ten years.

In this tactical analysis and scout report, we will examine how Gustavo Quinteros brought a struggling team back into form and rejuvenated one of the worst attacks in the league by examining what CA Vélez Sarsfield have done with the ball so far this season.

Gustavo Quinteros Formation & Players Used

While Gustavo Quinteros tactics have used many formations throughout his managerial career, he has been consistent with using a 4-2-3-1 as his base formation at Vélez Sarsfield so far this year.

In terms of players, Quinteros has done what Vélez excelled at during the last couple of years and promoted several academy players to the first team.

In goal, Vélez signed a new number 1 for Quinteros before the season started in Tomás Marchiori, who has started every game he was available for so far in 2024.

In defence, Quinteros uses academy graduate Valentín Gómez as his left centre-back.

During the season, former Olympique Lyon player Emanuel Mammana won the starting RCB spot from Aarón Quirós and formed the centre of the defence with Gómez.

At full-back, Quinteros puts his trust in experienced Elías Gómez and another Vélez academy player, Joaquín García.

The double-pivot consists of captain Agustín Bouzat, who played under Quinteros at Colo Colo, and another academy graduate, Christian Ordóñez.

In attacking midfield, the trio of Claudio Aquino, Francisco Pizzini, and (academy player) Thiago Fernández have earned the starting spots this year.

In the attack, 33-year-old Braian Romero gets the starts as the lone man upfront.

Quinteros has been rather stubborn with his starting players, barely rotating in the key competitions, Liga Profesional and Copa de la Liga, so far throughout this season.

Vélez Sarsfield’s Strong Attacking Play

For this article, we will take a deep dive into the attacking play that elevated Vélez from being one of the worst teams in the league to playing an incredibly successful season so far.

As we all know, attacks do not start after reaching the final third; attacks start after regaining possession.

In the upcoming paragraphs, we will examine the three phases of possession play for any football team in the world: build-up play, transitional play, and attacking play.

Build-up play is the first phase of attacks, with the ball being at the feet of your own defenders.

In this phase, it is crucial to establish a foundation for the attacks, adjust the positional play, cope with the opposing team’s press, and show great ball security.

Transitional play involves transferring the attack from your defenders into the final third; finding ways to play through the opposing team’s formation and get your attackers into good positions is crucial.

Finally, attacking play is the phase of actually creating goalscoring chances in the final third of play, finding ways to beat opposing defensive lines, and creating space for your attackers to get shots off.

First, we will take a look at the build-up used by Quinteros’ men so far this term.

Build-Up play: Attracting the press with short passes

If we take a look at the build-up, at first, we have to take a look at the shape that Vélez are using when they are in possession.

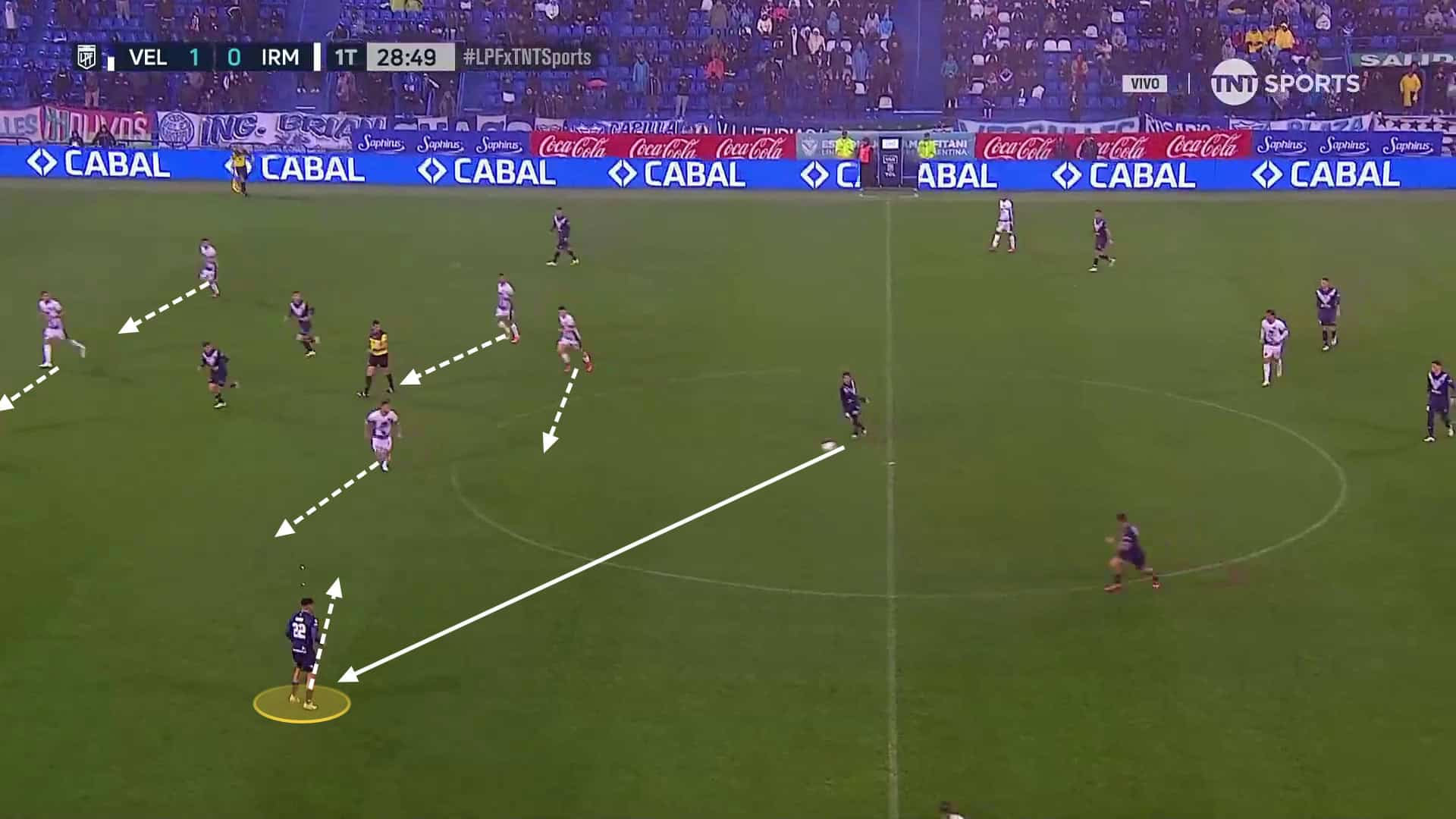

Usually, the team positions themselves in the way pictured above.

Quinteros likes his men to line up in a V-shape, with both centre-backs moving into the half-spaces, both full-backs staying in the first line of play but on the outside and the ‘keeper covering the centre of the pitch and being an active player as well.

The midfielders are doing something different, while one of the two players drops deep to help out his defenders.

Usually, the lone holding midfielder is controlled by an attacking midfielder of the opposing team, but he has not held an essential role at this stage of play so far.

Opposing teams do not press Vélez at this stage.

With four players in their first line of play and the goalkeeper actively involved in the passing game, pressing there would be useless because there is zero chance that the striker could apply pressure to the ball.

The interesting thing is Vélez Sarsfield want to be pressed.

For a long time, managers wanted their teams to avoid the opposing teams‘ press to avoid pressure on defenders and reduce the number of mistakes made that way.

Over the last couple of years, we have seen a trend of managers luring opposing teams into their press room by actively attracting the press.

But why? The answer is rather simple: pressing high up the field is risky as well.

By committing multiple players forward, teams are exposing spaces that the team in possession can use to progress their attacks.

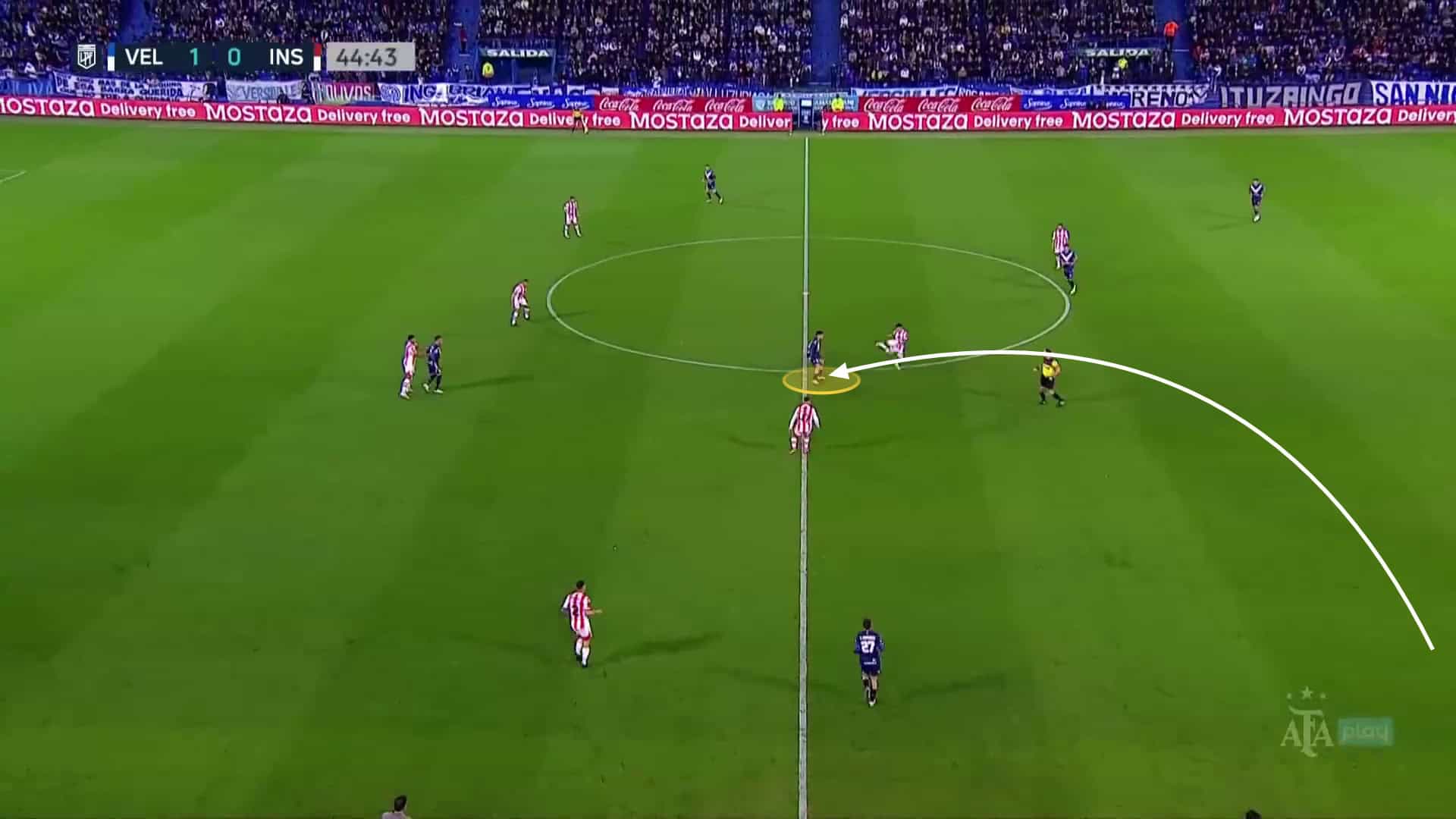

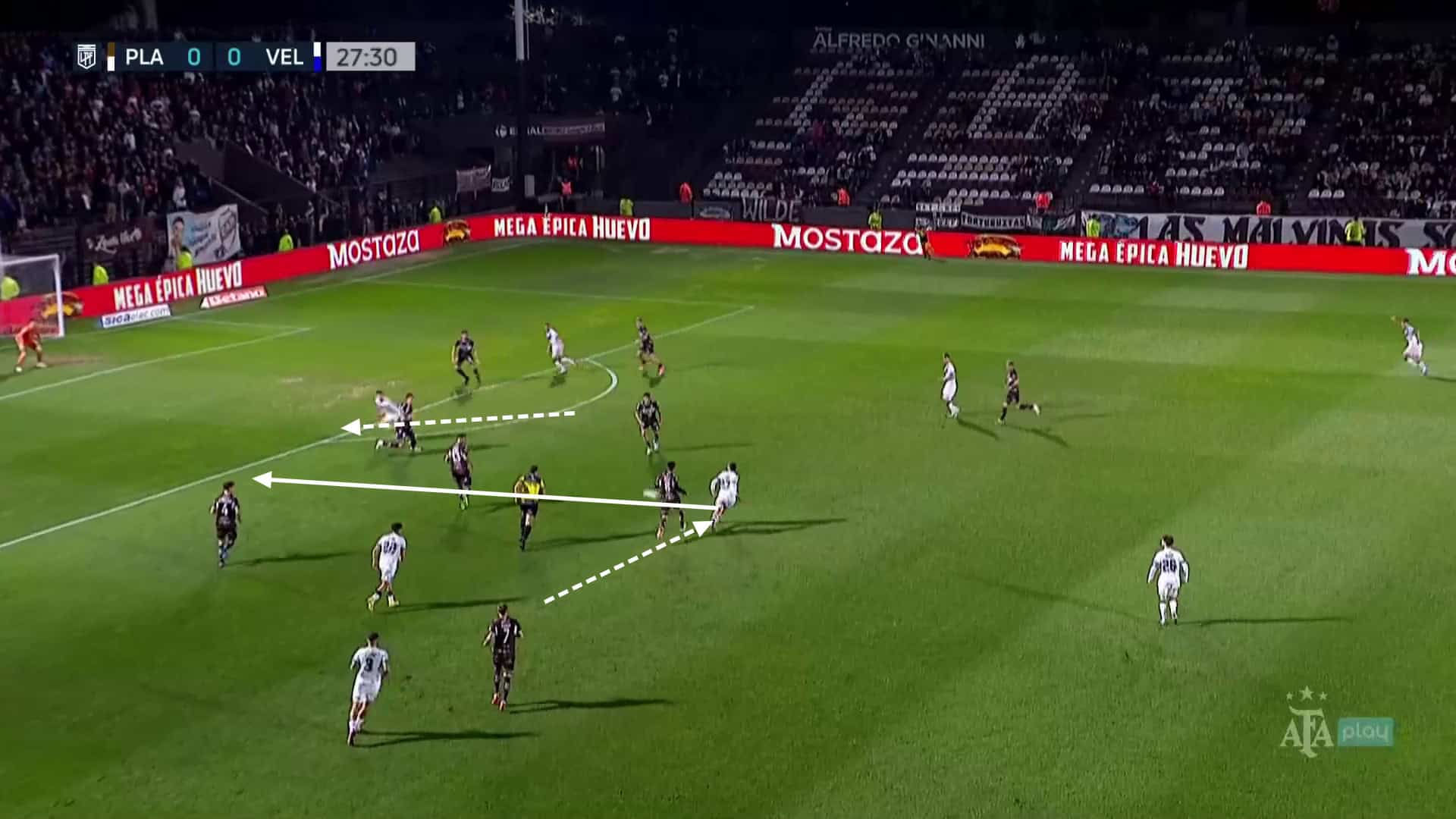

Vélez trigger their play through passes from the centre-back to the full-back.

This picture shows the situation after the centre-back passes the ball outwards to his left-back.

The positional play of Vélez adjust to this as well, with the holding midfielder coming towards the left side and the left attacking midfielder dropping closer to the left-back as well.

This attracts the press of the opposing team, which has two effects that Gustavo Quinteros intends it to have.

Firstly, the opposing team’s midfield is stepping up to engage in the press, creating space in between the line for Vélez.

Secondly, in modern football, all teams play ball-oriented football, and the opposing team is forced to move towards the left side of the field, creating a direction of play.

As seen in the picture, every San Lorenzo player is moving towards the left side because of the pass and the numerical advantage created by Quinteros’ men on that side.

If San Lorenzo does not move outwards, Vélez will just play their attack through the four players on the left side, but no team will allow that to happen.

Here, striker Romero uses this to his advantage.

He moves in the space behind the upstepping midfielders and receives the ball against the direction of play, finding himself in acres of space.

With just one pass, Vélez Sarsfield attracted the press, and with just one more pass cut right through, the attack progressed into its transitional stage.

But it’s not just the strikers that are being used as target men by Gustavo Quinteros.

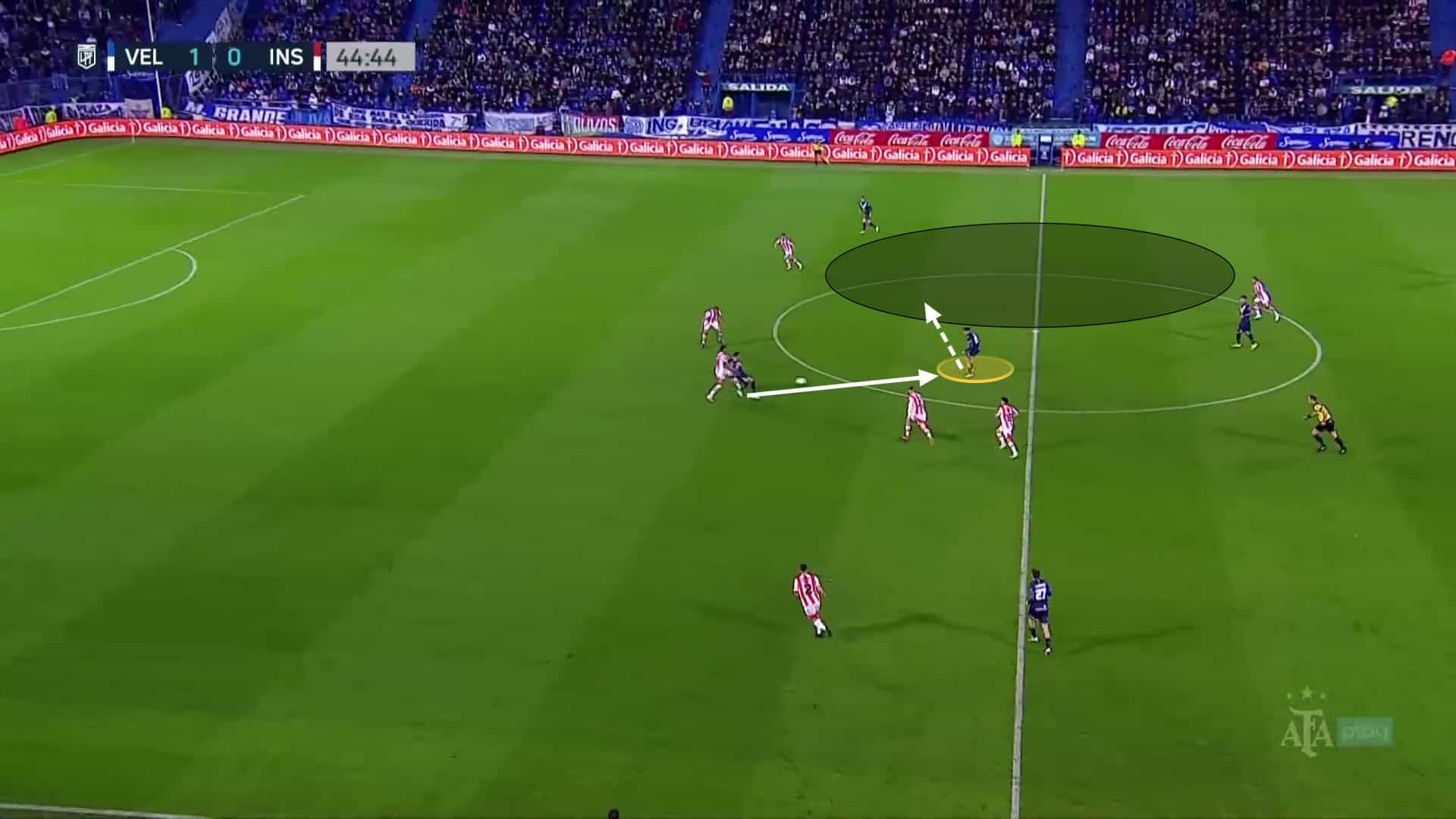

Here, we see an example of Vélez’s build-up play against Barracas Central.

The initial situation is the same as the first situation showcased in this article: Vélez start their build-up in a V-shape, with one midfielder dropping deep and being controlled by the opposing attacking midfielder.

There is one key difference here, however.

Vélez are already leading the game, and Barracas are already triggering the press onto the goalkeeper, forcing Vélez to trigger play there.

Once again, the ‘keeper passes the ball to one side, the attacking midfielder drops deep, and the holding midfielder moves to the right side as well.

This creates a direction of play and space between the lines again.

This time, the far-sided midfielder is using the space to move in there and receive the ball against the direction of play once again, finding himself in open space.

While Vélez were not able to break through the entire opposing midfield this time, they still were able to break the first line of press and progress the attack into its transitional phase.

But what if these things don’t work and Vélez can’t find solutions against the attracted press?

Well, the team is not afraid to play long balls in the space between the midfield and the defensive line.

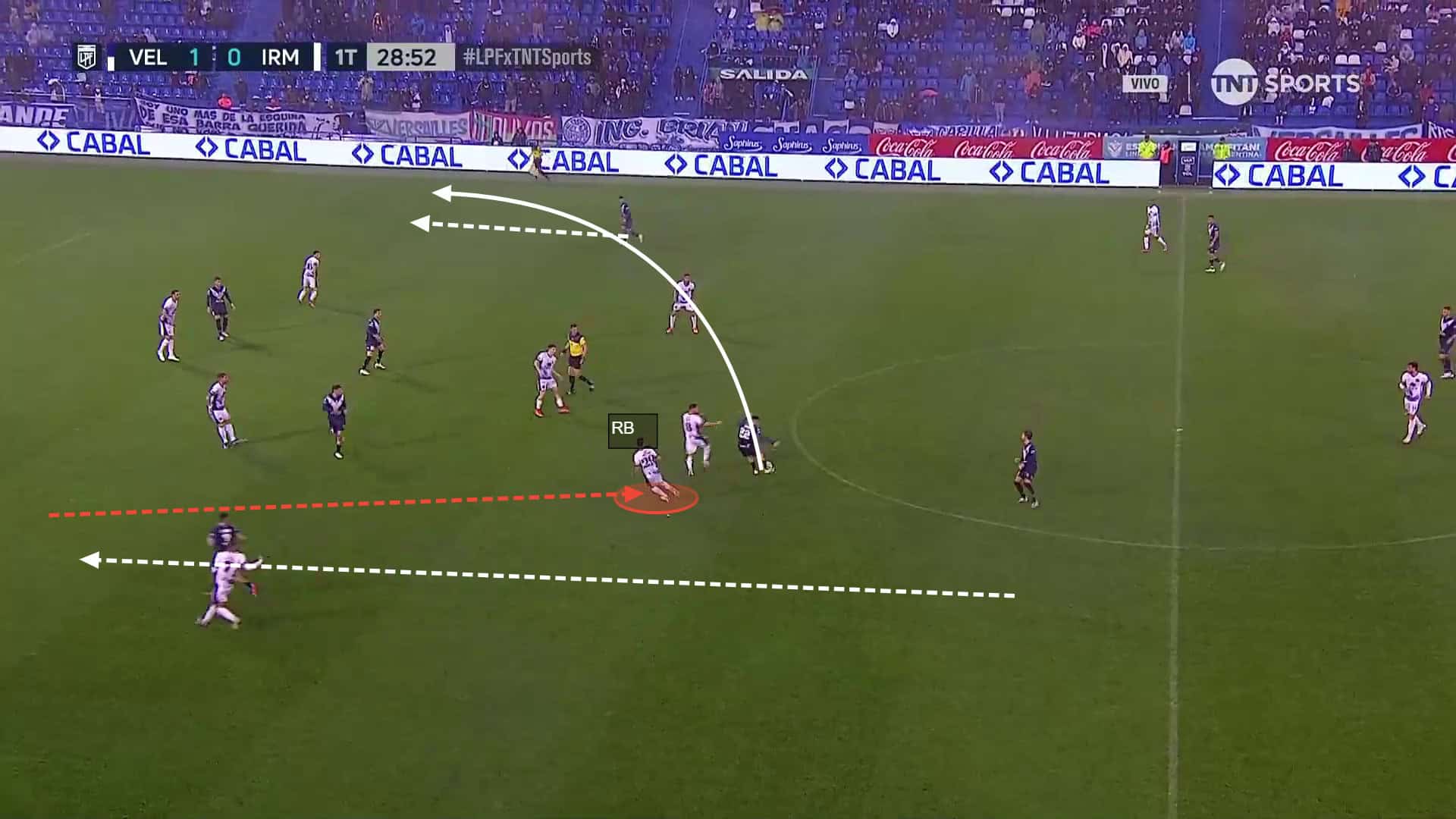

Here, we can see a long ball to the attacking midfielder played by the right-back under pressure.

With the space between the lines still opened up, long balls towards this space are very effective for Quinteros’ men because the midfielders are usually not able to recover in time to contest possession there.

So, to sum things up, there are three fundamental principles to Quinteros build-up play at Vélez Sarsfield:

- Attract the press to one side of the field

- Find space in between the lines and in the half-spaces

- Play the passes against the direction of play

Transitional Play: Switches And Carries

After build-up and finding space between the lines and in the half spaces, Vélez now need to find solutions to progress their attacks to the final third.

While their build-up play is very effective, it also has one big downside: the distance they need to cover is as big as it gets for a football team, from their own box into the opposition’s box.

But as with the build-up, Gustavo Quinteros gave his team multiple solutions at hand to progress the ball quickly here as well.

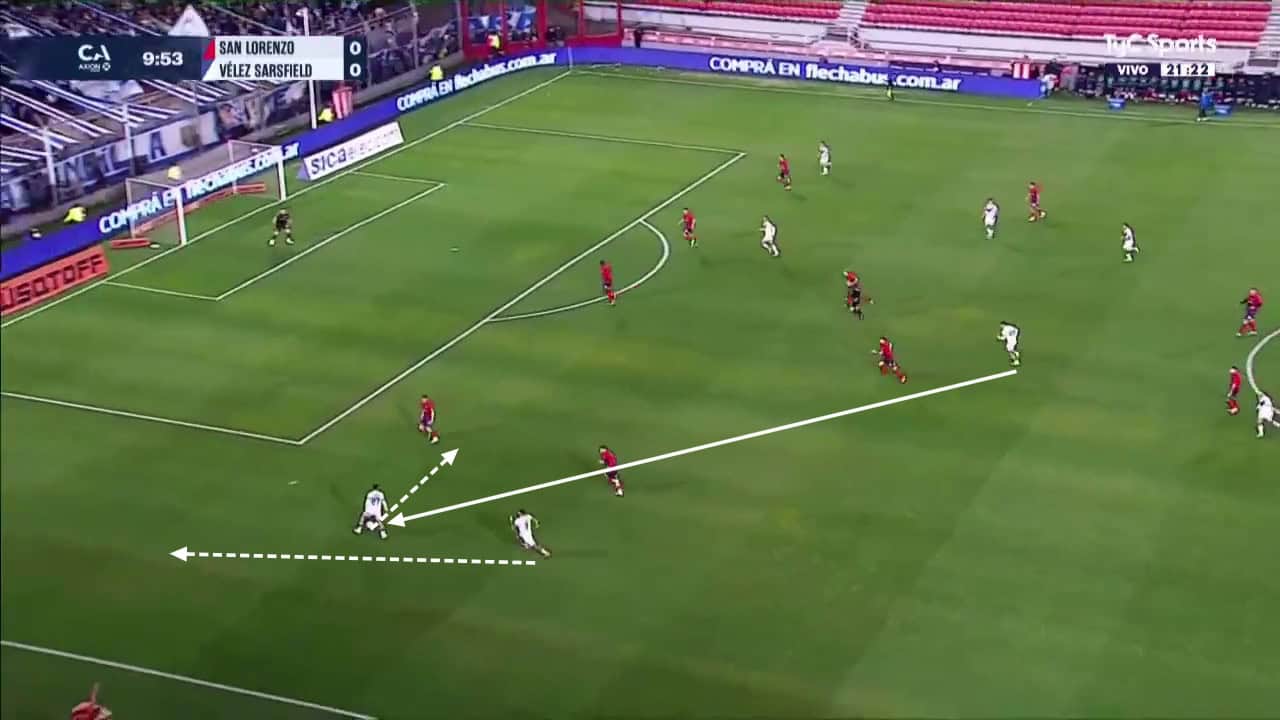

Let`s take another look at the first situation we have seen in this article.

After the striker Romero dropped into midfield to receive the ball, the attacking midfielder moved forward into the striker position to keep the opposing team’s defensive line busy.

Romero plays an easy layoff to the holding midfielder here, who now has the field in front of him and can scan down the field.

With all San Lorenzo players committing to the press on the right side, with even the far-sided winger and full-back nearly in the centre of the pitch, this obviously opens up space on the far side of the field for Quinteros’ men.

Without a second thought, the midfielder plays a switch against the direction of play to the far-sided winger, who is isolated on the right side in a lot of open space.

Once again, just two passes opening up the opportunity to progress the ball into the final third and force the defence to react once again, changing the direction of play for the second time.

From there on, the right attacking midfielder of Vélez just can carry the ball into the final third, bringing the attack into its final stage and even opening up the possibility of a take-on attempt in a 1v1 situation on the outside.

However, switches are not the only transitional principle Quinteros’ men can use efficiently.

Let’s take a look at the second situation again as well.

After receiving the ball, the two midfielders play a quick one-two, allowing one of them to carry the ball with his face towards goal.

This also forces the defenders to react because the carry also goes against the direction of play, changing it for the third time in this situation.

This draws the right-back out of position and forces the midfielders to narrow down the space in the centre, creating space on the left wing.

Barracas Juniors are unable to recover in this situation and are forced to foul the ball carrier, which results in a yellow card.

Once again, two passes allow Quinteros‘ team to progress the ball into the final third and cause the defenders to scramble around without real orientation, creating chaos in the meantime.

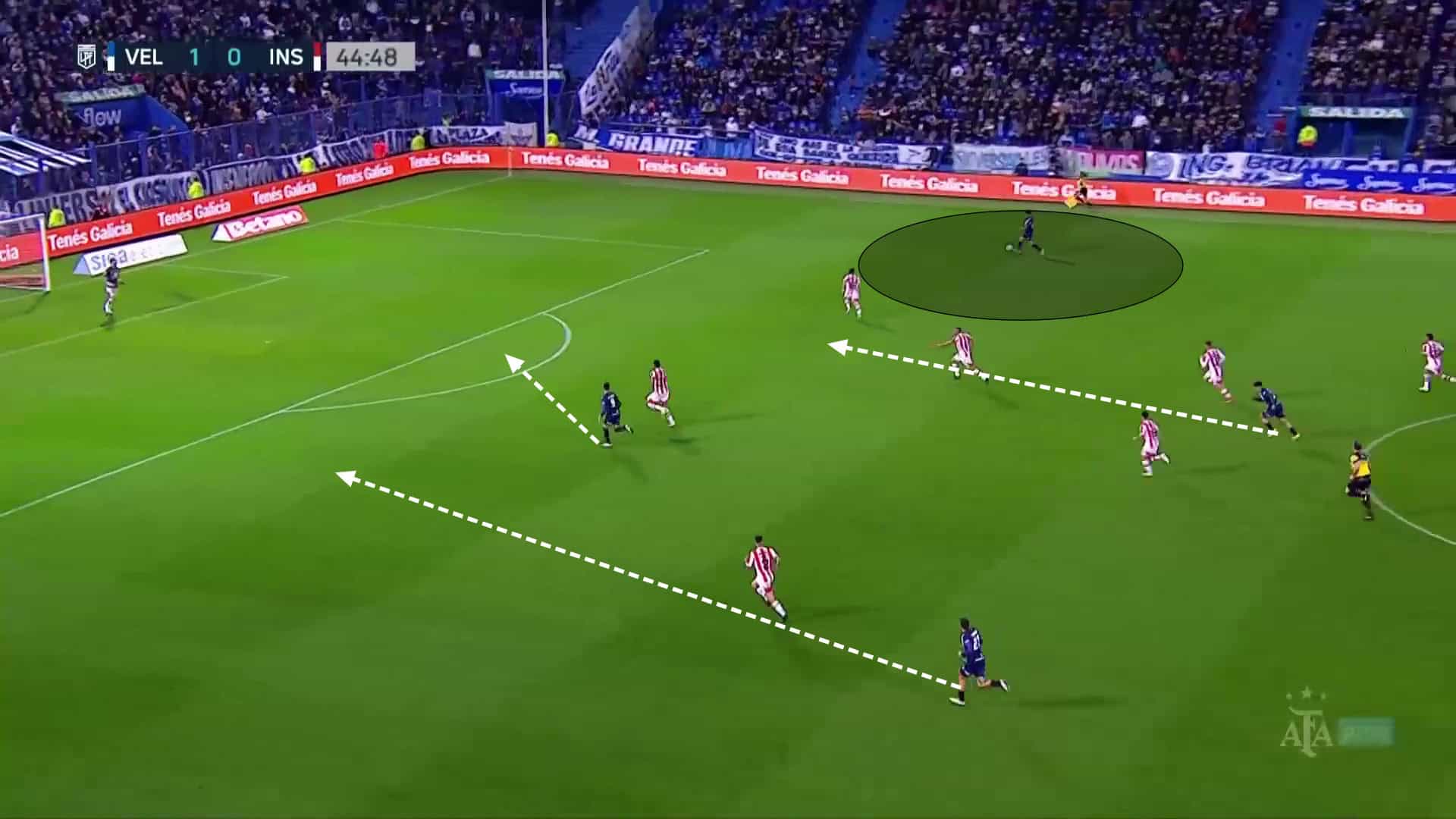

If we examine the final situation with the long ball again, we can see these same patterns of play once again.

After both the attacking midfielder and the defender missed the ball, the ball went through towards the target man in Romero.

He plays a quick lay-off towards his attacking midfielder, who instantly turns towards the far side of the pitch.

Because the defence committed to the left side of the field for their press, there is a lot of empty green in the right half-space.

He instantly turns and carries the ball against the direction of play, then switches the play to his right-attacking midfielder, combining the basic principles of transitional play that Quinteros wants to see from his men.

Vélez Sarsfield are executing these things really well this season, constantly forcing defences to scramble around, trying to regain some form of compactness after the first line-breaking passes or after the switches.

The constant changes in the direction of play are putting the defenders in a pretty tough spot.

They are forced to orientate themselves from scratch every couple of seconds, causing some disarray in the opposing team’s lines.

Vélez use this chaos they created very well to punish opposing teams for leaving space or not being able to change the direction of their movement fast enough to progress the ball quickly from their defenders into the final third.

Here, we can see the Vélez player on the right wing, with the defence trying to get back behind the ball and multiple attackers making runs towards the box.

It’s really hard for any defence to regain control of the situation in these types of attacks because defending with your face towards the goal is a very hard task.

With all Vélez players having a lot of momentum, they can also create a lot of power in the box.

Quinteros is using a COCO-principle to progress the ball in these situations.

COCO stands for centre-outside-centre-outside and is repeatable for an infinite amount of times.

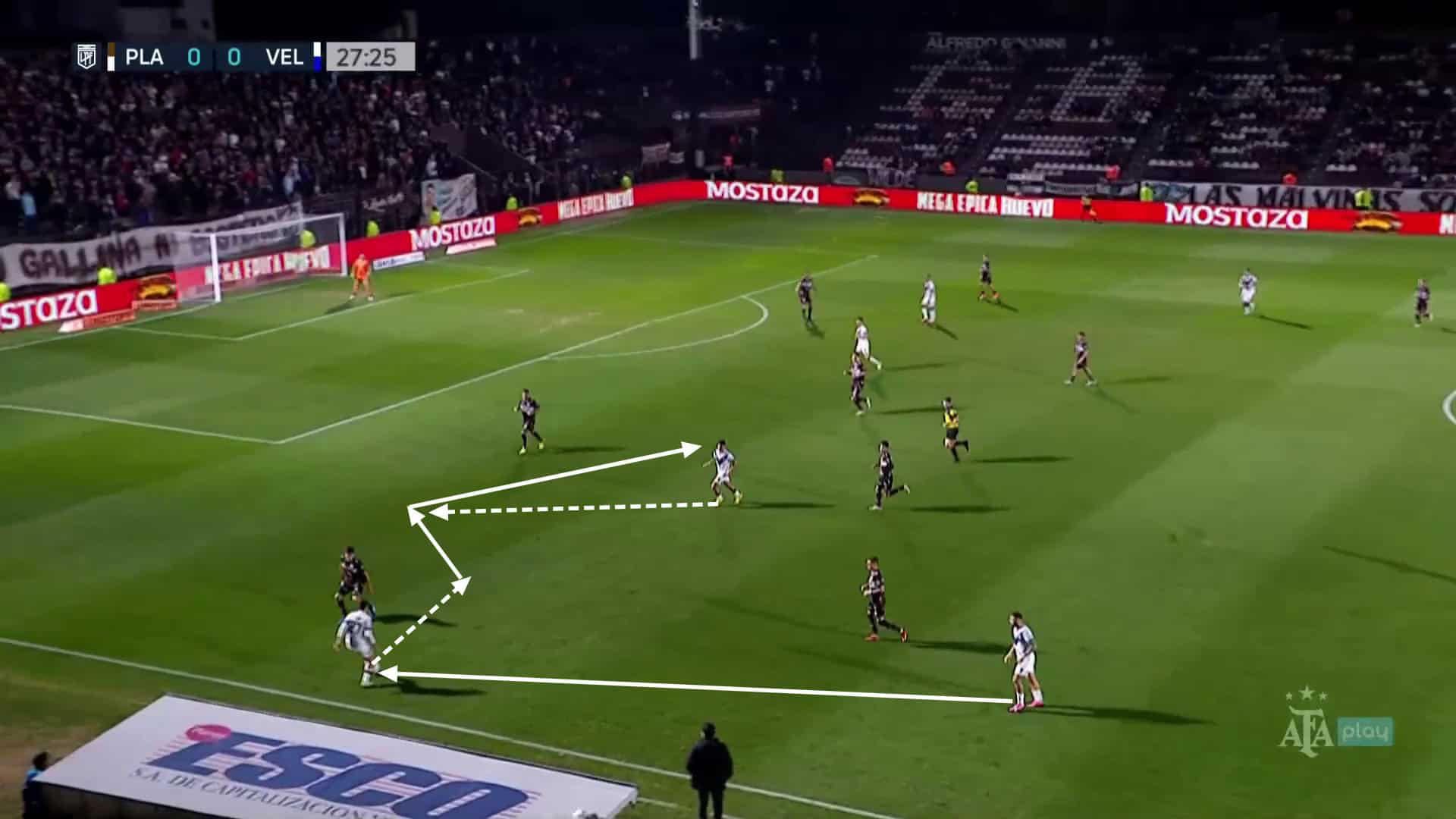

Let’s take a look at a situation that explains that in a more easy-to-understand way

Here, we can see the transitional play starting in the centre of the field or at least more towards the centre than to the outside.

The left-back then plays a pass to his left attacking midfielder, who turns inside with his first touch.

The central attacking midfielder is moving outside, so in the opposite direction that his teammate is moving.

Then these two are playing two quick passes, first to the outside, then back to the cutting winger inside – centre, outside, centre, outside.

This leads to the Vélez player moving inwards even further, with the striker moving behind the defence towards the outside, against the movement of the ball carrier – centre, outside.

But why are Velez doing that?

With these contrariwise movements of the ball and the players, the opposing defences are constantly tasked with moving towards the outside and then back towards the centre or even to the other side if play is switched completely.

This keeps the defenders moving and creates space for the attackers to find themselves in.

Another very positive aspect that Quinteros is using to gain an advantage for his men.

Changing direction is hard, so if the defender is closing out the attacker after the switch, it will be really hard to keep up with him if he moves in the other direction again.

The same goes for passes.

This allows the attack to always play at a higher pace than the defence, creating holes and space that Quinteros‘ men can abuse.

If you are looking at the arrows I used to mark the pictures, you can see them going in opposing directions all the time, which makes it impossible for the defenders to follow the movements.

Again, it’s rather simple football, but the continued success during this season shows that it’s hard to adapt for opposing teams, even if they know how Quinteros wants his men to play.

This situation against San Lorenzo is a perfect example of this and shows how efficiently Vélez transition their attacks.

After the opposing defence is committing to the right side, Vélez switch play quickly.

Fernández turns inside with his first touch, left-back Gómez is making an overlapping run, and the right-back of San Lorenzo is put in a spot where he has to change direction quickly and still won’t be able to prevent Vélez Sarsfield from getting into the final third.

Easy, fast, and well executed, Vélez are making the most out of Gustavo Quinteros’ principle in the transitional phase.

Attacking play: Cutting defences apart against the grain

As we have seen in the article so far, Vélez are not a team that progresses their attacks through the middle of the field but rather through switches to the wing or at least the half-spaces.

Their goal is to create goalscoring opportunities out of these positions, in which they receive the ball in the final third.

As we have seen in the transitional phase of the play, Gustavo Quinteros wants his men to play against the direction of play.

After the switches in transitional play, the direction of play obviously changes again.

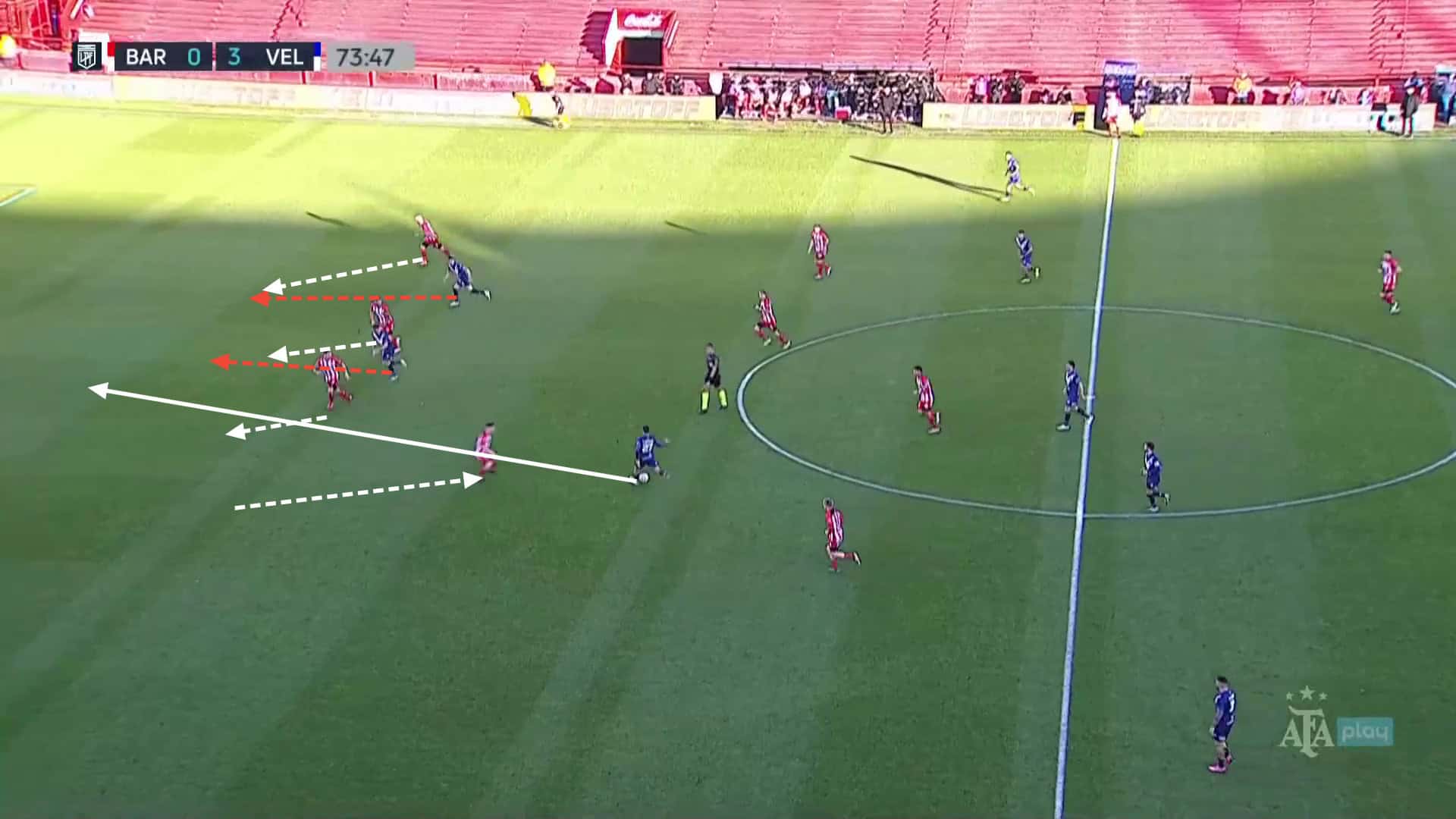

If we look at the last situation again, we can see that fairly quickly.

We can see San Lorenzo is forced to move to the left side of the pitch after Vélez switched play to their left attacking midfielder.

Thiago Fernández is moving inside quickly, against the direction of movement the defence is currently undergoing, forcing them to close him out.

In the centre of the pitch and the right half-space, two wide-open Vélez Sarsfield players are now waiting to receive the ball.

Fernández plays the easy pass to his open teammate, and as we can see in the picture above, the defence is now scrambling to regain some control of the situation.

With six players in the left half-space covering only two men, Vélez managed to open up multiple players in the final third for them.

Taking a look at the right side, the San Lorenzo left-back now has two men he needs to cover.

Because his teammates are committed to the left-hand side, they can’t change the direction of their movement fast enough, and they have to account for the threat of a shot by the Vélez player with the ball.

No one is able to help him out.

In this situation, the defender usually defends the centre of the field because one of the most basic principles of defence is always prioritising the centre over the wings.

However, in this desperate situation for him, the left-back decides to gamble and tries to cut off the pass to the outside, opening up the passing window for the deep run in the middle of the field.

That’s an easy pass for a professional footballer, resulting in an easy goal for Vélez Sarsfield.

As previously mentioned, Gustavo Quinteros wants his men to play against the grain, against the direction the defenders are moving.

Vélez always try to find passes to the far-sided half-space because after overloading one side, they can isolate a player there and keep the defense moving to create holes.

It also creates small advantages for the Vélez players in their direct sprint duels.

Vélez Sarsfield do this in other situations as well.

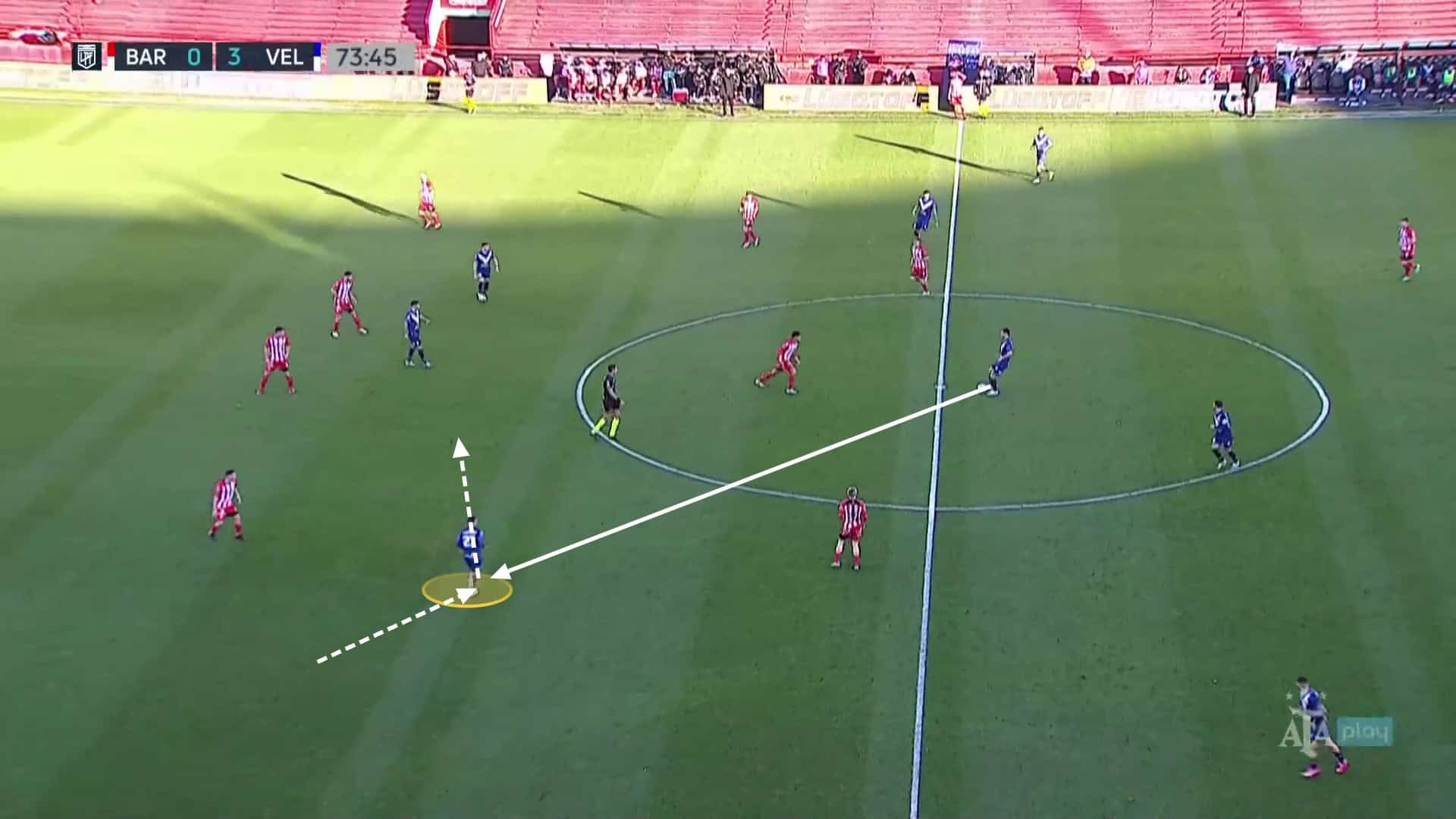

Later in the game against Barracos Juniors, Vélez were already leading 3-0, and Barracos was not interested in pressing the first line of play for Vélez anymore.

This freed up the holding midfielder, who could even turn around.

The 4-3-2-1 is extremely narrow in these situations, with only the full-backs providing width for Quinteros’ team.

This little twist in positional play allows the outside attacking midfielders to receive the ball in the half-spaces.

Thiago Fernández is moving into the half-space, receiving the ball from his midfielder.

This also drags the right-back out of position because he needs to press him, but because the movement is in contrast to his movement after the switch, he cannot contain Fernández.

Vélez use their zig-zagging of movement once again, then, with the two other attackers in the front line, moves in behind the defensive line, against the direction of Fernández’s movement, exploiting the space behind the right back.

Fernández then plays the easy through-ball to his striker, who clinically finishes the opportunity to put the game to rest for good.

If Velez had committed 100% to this situation, it also would have opened up the passing lane for another switch outwards to the overlapping right-back.

Still, because Barracos was caught off-guard with the first pass anyway, there was no need for that.

Once again, two actions with contrarian directions of play put the defence on their back foot and opened up opportunities for Quinteros’ men.

Now, let’s take a look at one last goal of Vélez Sarsfield, which showcases all of the things mentioned above in the team’s attacking phase.

In the game against Independiente Rivadavia, Vélez were the clear-cut favourite from the get-go.

Once again, Quinteros’ men attracted the press onto their right side and switched play through their midfielder out towards Thiago Fernández in the half-space.

Fernández turns inside with his first touch once again, moving against the direction of play and against the direction the Independiente defenders are moving.

Because Independiente was committed to the press on the right side, their right-back needed to step up into the left half-space to cover Fernández.

With his movement, Fernández easily gets past his marker.

With all defenders moving towards the left side, he can switch play once again against the direction of movement towards his freed-up teammate on the right wing.

Left-back Gómez makes a run in the space the right-back vacated to press Fernández in the meantime.

Ordóñez has enough space on the right side to easily get his cross off without any real pressure from a defender, and of course, the cross also goes against the direction of play.

With all defenders moving towards the right wing, they do not see that their right-back was not able to recover in time, and Gómez is in acres of space at the far post.

The cross finds its man at the second post, and Gómez makes it 2-0 with a wide-open header, putting the game away in the first half already.

Conclusion

After a couple of rough years, Vélez Sarsfield are making some noise in Argentine football again, and head coach Gustavo Quinteros is the main reason for that.

Not only did he perfectly fit the club’s philosophy of developing the young players from their academy, but he also managed to instate a couple of key principles in possession that make Vélez one of the most dangerous teams on the attack in Argentina right now.

By constantly attracting the press and attacking the so-created space between the lines and in the far-sided half-space, Vélez are able to transition their attacks from their build-up into the final third extremely quickly and covers a lot of distance with few passes.

In attack, the team constantly keeps the defence moving, changing the play of direction multiple times per attack and always moving against the grain to gain advantages and keep the defence discombobulated.

With the COCO principle, Quinteros managed to give his team easy-to-execute solutions in all phases of play.

Their zig-zagging movements and passes make them extremely hard to defend.

After finishing as the runner-up in the Copa de la Liga, Vélez Sarsfield are currently leading the Liga Profesional at the halfway point of the season with no signs of slowing down.

With Gustavo Quinteros‘ tactics and their strong form, the young team could cap off one of the biggest turnarounds in the last couple of years by ending the silverware drought and bringing home the first championship since 2013.

Comments