Two teams at opposite ends of the table faced each other in the 2. Bundesliga on Monday night as VfB Stuttgart faced 1.FC Nuremberg. It was a game that went the way many people thought, with Nuremberg struggling and recently appointing new manager Jens Keller, while Stuttgart were looking to maintain their push for promotion under the excellent coach Tim Walter. As a result, the game was a pretty familiar one to Stuttgart, with them being tasked to break down a deep block of bodies for 90 minutes. a situation which Tim Walter’s philosophy and tactics are built on solving. In this tactical analysis, we will look at the build-up patterns and strategies of Stuttgart, and look at how their offensive structure allowed them to break down a resolute Nuremberg side.

Lineups

Stuttgart lined up in a 4-3-3 but didn’t stay in any fixed formation due to their fluent build-up play, with their most common formation resembling more of a 3-3-4 or a 3-2-5 at times. Nuremberg meanwhile used a 4-5-1 and stayed extremely deep looking to remain as compact as possible and grab a goal from a counter-attack, set piece or long ball.

Asymmetrical structure

Stuttgart were extremely lopsided in their build-up play as a result of their structure, and particularly the movements of right-back Pascal Stenzel.

In conventional build-up using a back four, should the full-back receive the ball they would usually be positioned high and wide, and look to stay in this wide area and either stretch the play or progress the ball down the wings.

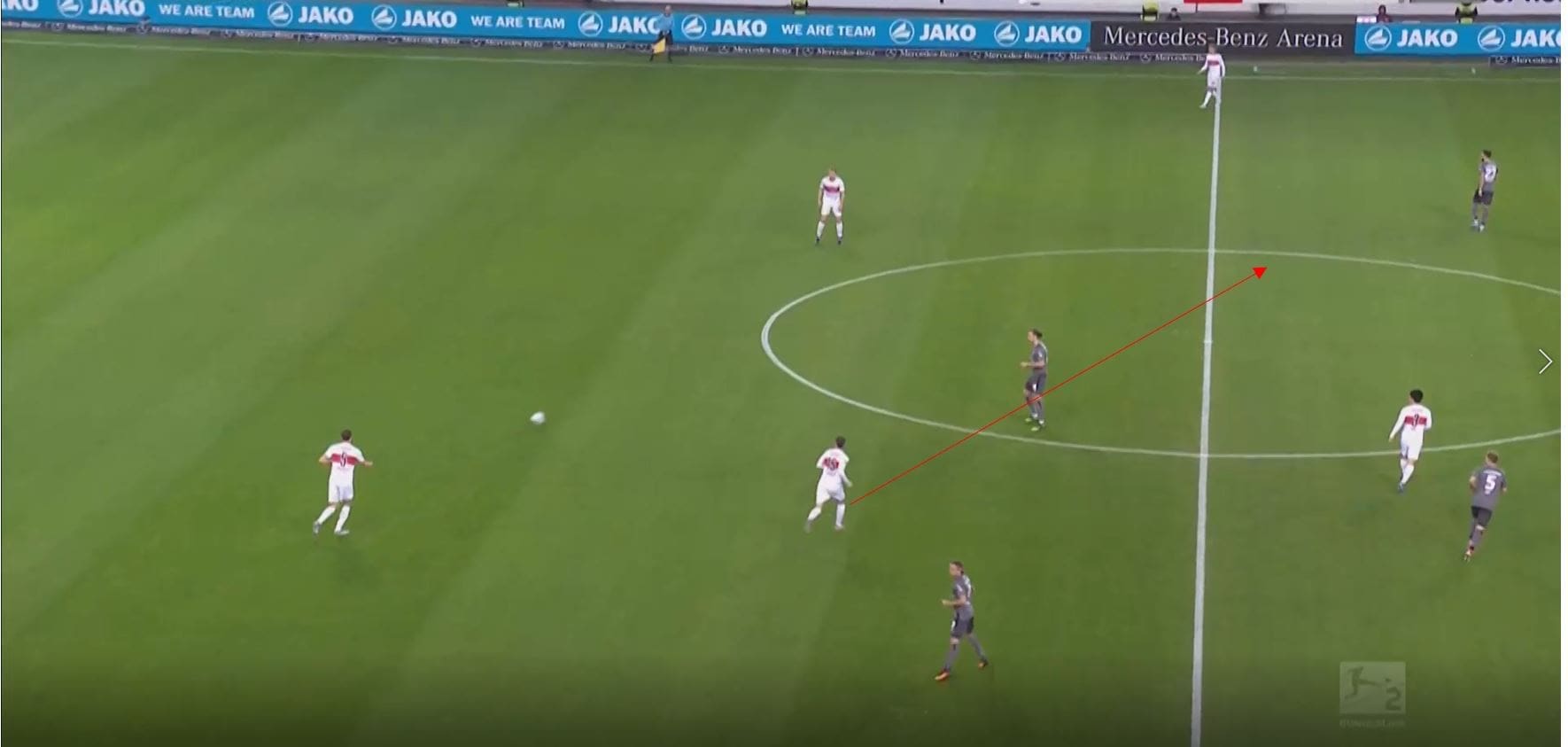

However, as we can see below when Stenzel played the ball inwards to a centre back, he would also make an inwards run and occupy the empty pivot space, which is something we will come onto later. Stenzel plays the ball and then makes his movement towards the left side of the pitch, ready to receive the ball where typically a number six would receive.

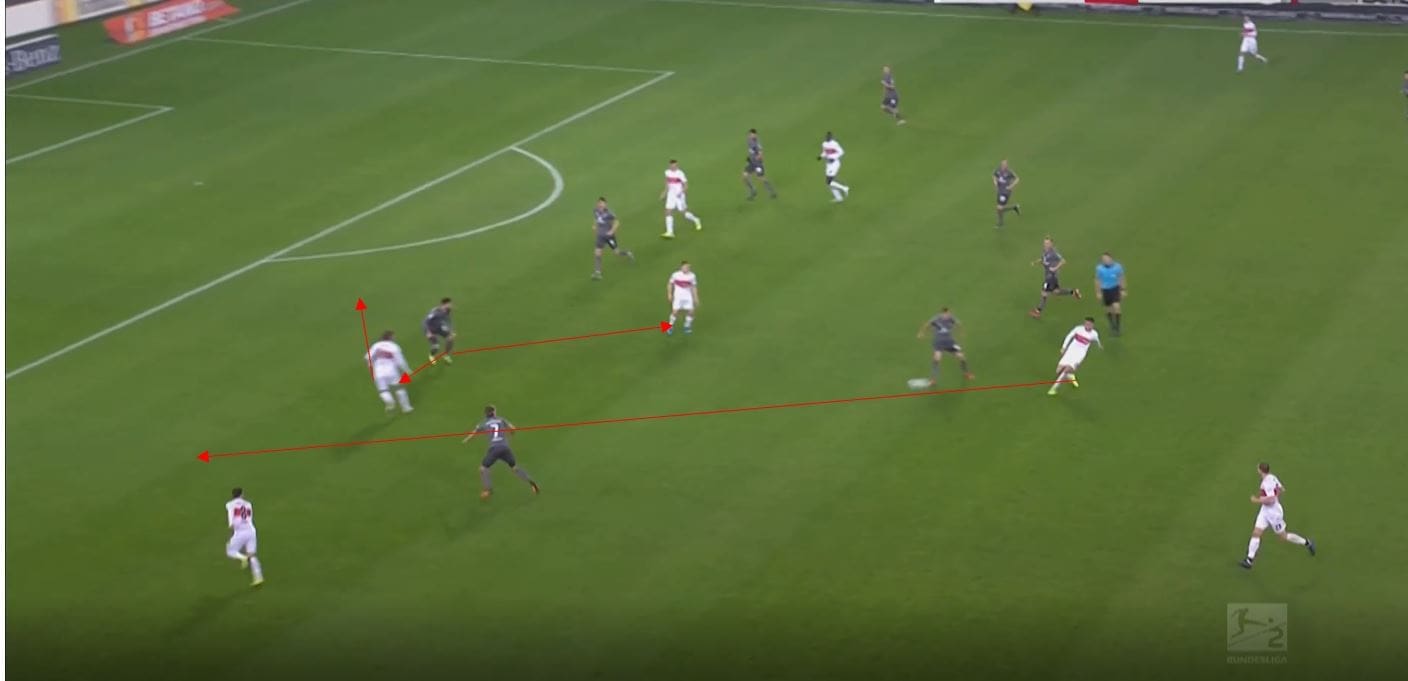

Below we can see Stenzel receiving the ball in this area, where his pressed by a midfield player from the opposition, we can also see a key part of Stuttgart’s gameplan in numerous players between the defence and midfield of Nuremberg, all looking to create find passing angles to receive. This build-up structure allowed Stuttgart to advance past the first line very easily as we can see below.

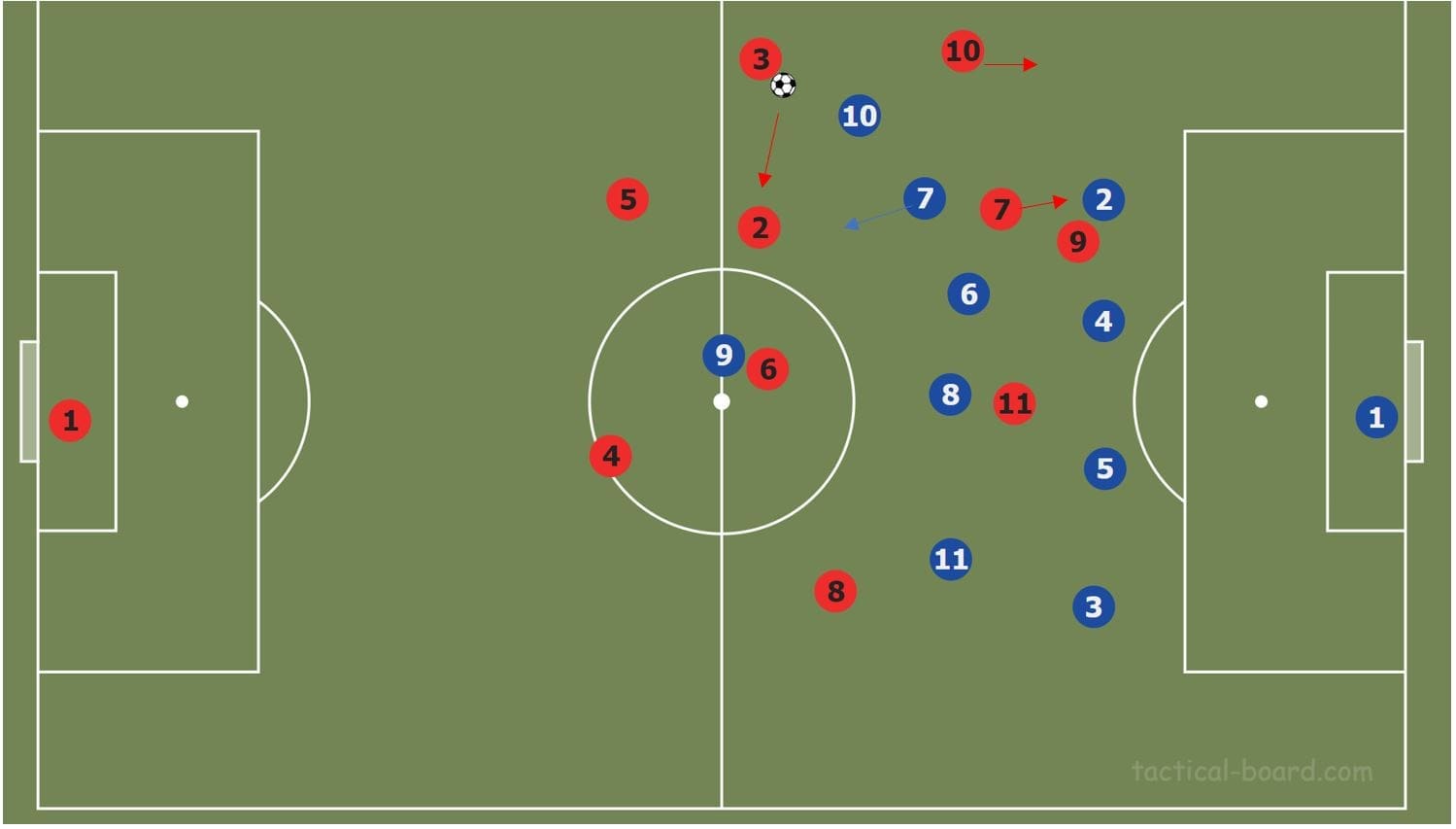

We can see a diagram here of both side’s structures in this kind of situation. Stenzel (number two) would push across to receive alongside Wataru Endo, while Gonzalo Castro a number eight would take up a more conventional right-back position, although still quite narrow. Meanwhile, on the left side of the pitch, Stuttgart would attempt to create overloads and left-back Borna Sosa played as a high and wide full-back, whose main job was to stretch the play and open passing lanes. We can see in this particular example below the full-back stays wide and pins the number ten, while the number seven presses Stenzel, who takes up a narrow position in order to better open the passing lane between the ten and the seven. Stuttgart then look to create an overload around the full-back, with almost a 3v1 created.

Benefits of fluidity in possession

There are a few advantages to using this structure that were evident within this match. Using this structure in which players move freely within positions and move into space to receive rather than waiting within space is a key principle of Tim Walter’s attacking play, as analysis of this game shows.

We can see below another example of the full-back creating an asymmetrical shape in the build-up with a short pass and then movement inside. The pass is played while being pressed by the opposition winger, in a man orientated manner.

This movement inside immediately loses the marker and creates space for Stuttgart to exploit. The movement of the winger to press creates space on the wing for a player to move into and because the full-back drops into this central area to receive, Stuttgart have many players already within the central areas to create an overload with. For example, if any of the nearby Nuremberg midfielders move to press, they leave their midfield partner in a potential 3v1. We can see the winger for Stuttgart moves wide into this area, which gives space for a pass to be played within the halfspace higher up the pitch, should one of the midfielders drop.

Consider if a pivot had dropped into Stenzel’s position and Stenzel remained wide, Stuttgart would have less options available to create that central overload of effectively a 4v2, and although would potentially have some more space due to the full back stretching the opposition, they would not create the massive amount of space seen out wide. A pivot player within this area would also likely be followed fairly routinely by an opposition midfielder, and therefore Stuttgart may be forced back.

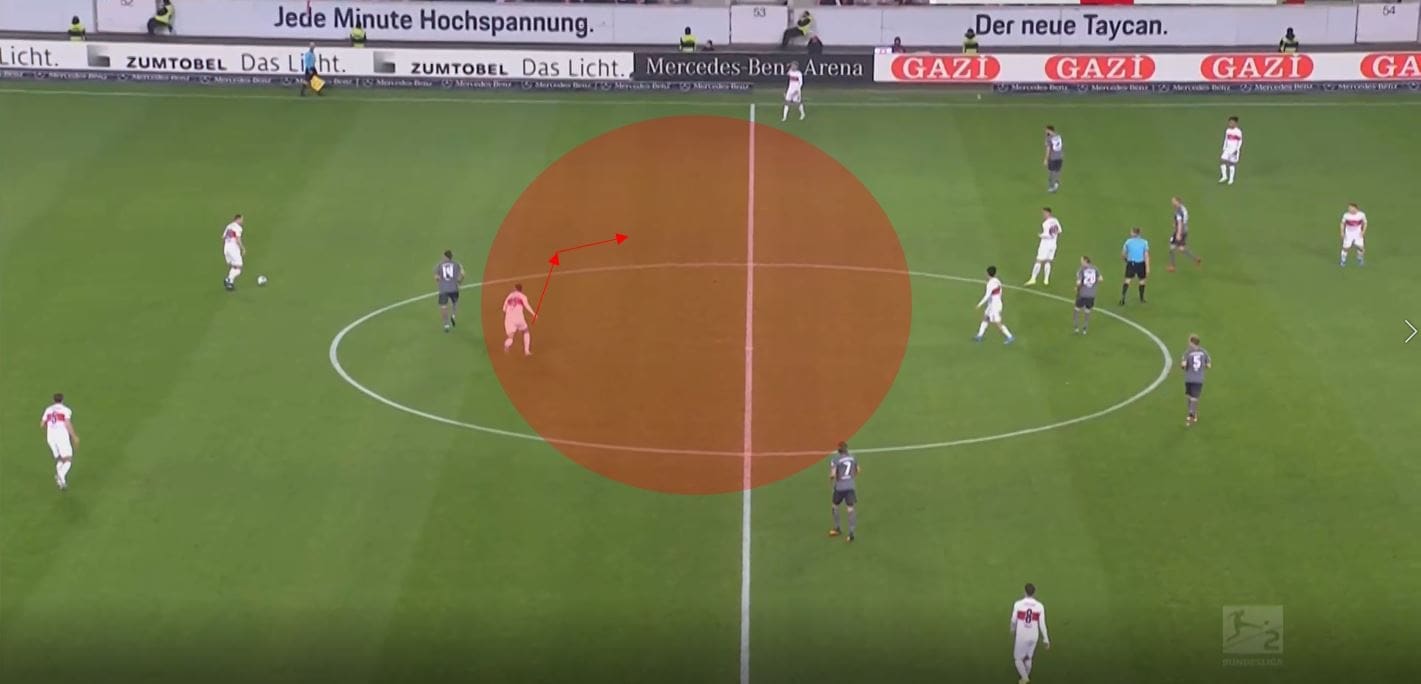

Body orientation

Another advantage of this kind of fluidity in the build-up is body orientation. By emptying the pivot space, Stuttgart allow players to arrive into space and receive the ball, but the orientation at which they receive the ball is important. If a pivot drops to receive the ball, they will have their back to goal and are automatically easier to press into going backwards, whereas as we can see below, if players arrive into the space from an angle they can receive the ball at a better angle and can, therefore, progress the ball more cleanly and in a forward direction.

Impact of asymmetry on the game

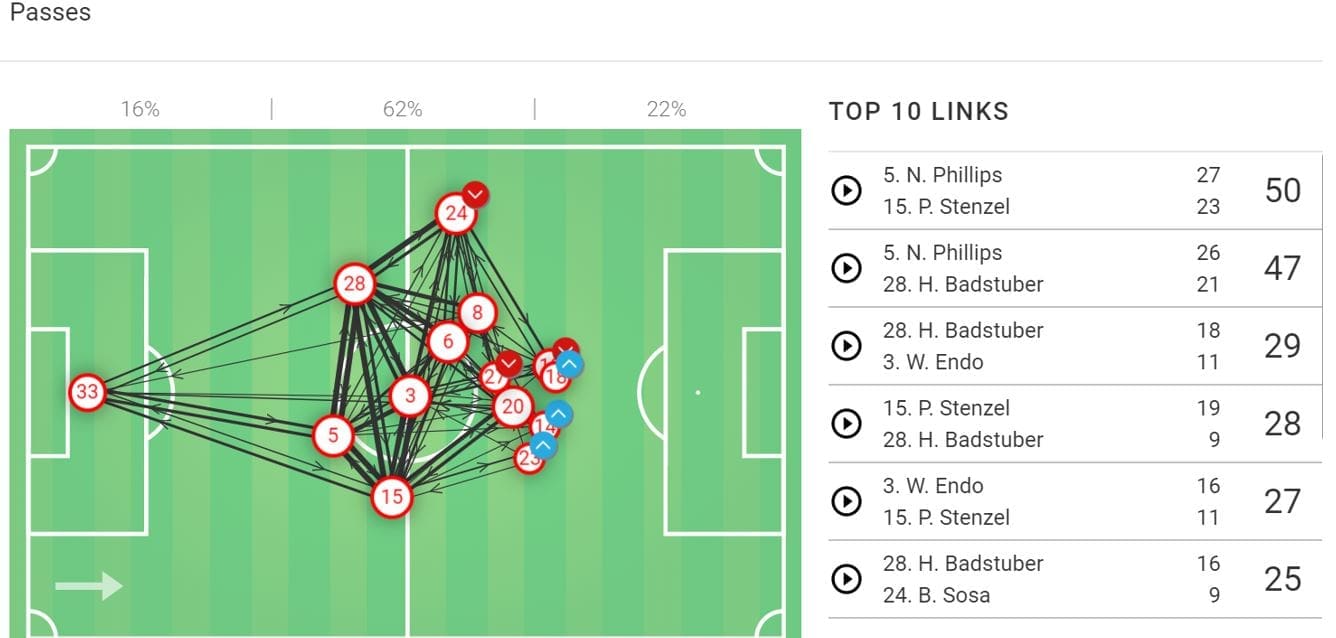

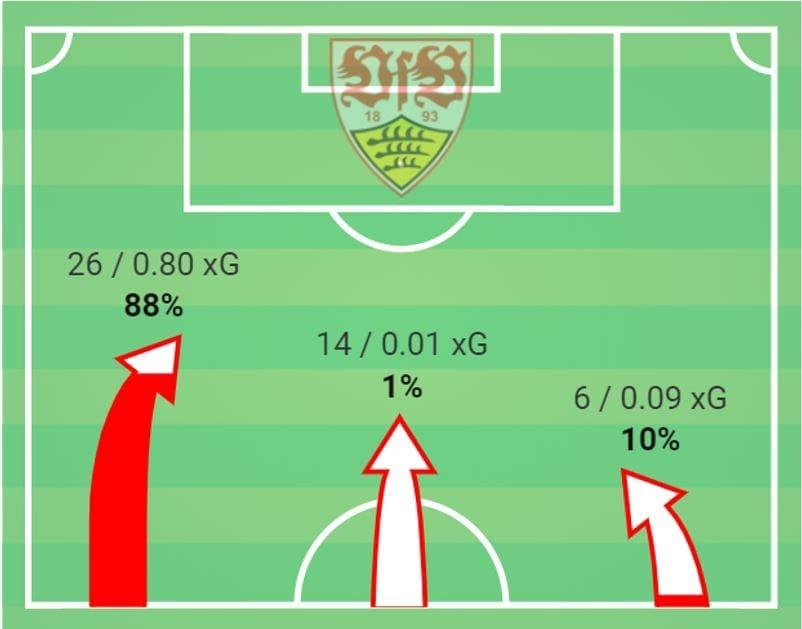

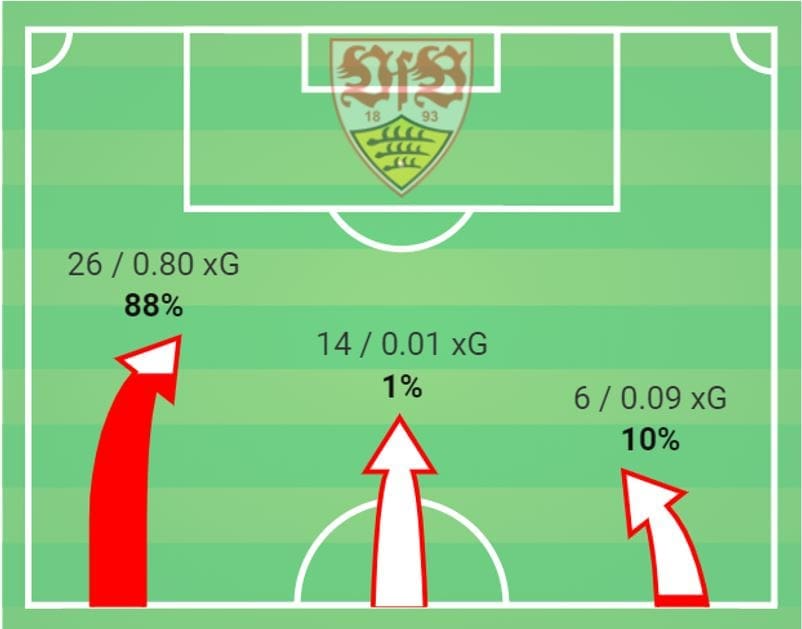

As a result of this asymmetrical build-up, the game took on a clear pattern as we can see from the statistical images below. We can see some proof of the asymmetrical structure in the passing links below, with Stenzel (number 15) much narrower than his left-sided counterpart Sosa. Stenzel was also involved in the top link between himself and on-loan Liverpool defender Nat Phillips.

As a result of not having a high and wide right full-back, Stuttgart couldn’t play from the back down the right side. Any passes that did go to the right tended to be long passes that relied on them to beat a man individually. Therefore, it’s no surprise that Stuttgart heavily favoured the left side in their build-up and generated by far the most xG from it. This stat excludes the penalty xG, which was won from a corner on the left side.

Space creation

As mentioned earlier, a key part of Walter’s teams’ play is to arrive in space to receive the ball and create space, and we can see a few examples of this happening below, where Stuttgart required more quality in order to use the spaces they created, something I suspect Tim Walter will be looking to get should Stuttgart gain promotion.

We can see an example of space creation using movement below, where one midfielder empties a zone and another player drops into space. The player who has vacated the space also drags his marker with him and commits him to a central position.

We can see here two Stuttgart players commit themselves to the wide areas to draw their markers from the central areas, which opens up the passing lane to striker Mario Gómez. Stuttgart then use a third man run with the midfielder highlighted furthest from Gómez dropping in to receive in the space he and his teammate have created.

Here Stuttgart create an overload on the right full-back of Nuremberg, with a central player occupying him slightly and two wider players also. The nearest player to the marker makes an inward movement which drags the marker further away from the actual pass and opens the passing lane further, but Stuttgart can’t take advantage. This overload on the full-back was common due to the asymmetrical shape employed.

Stuttgart still improving

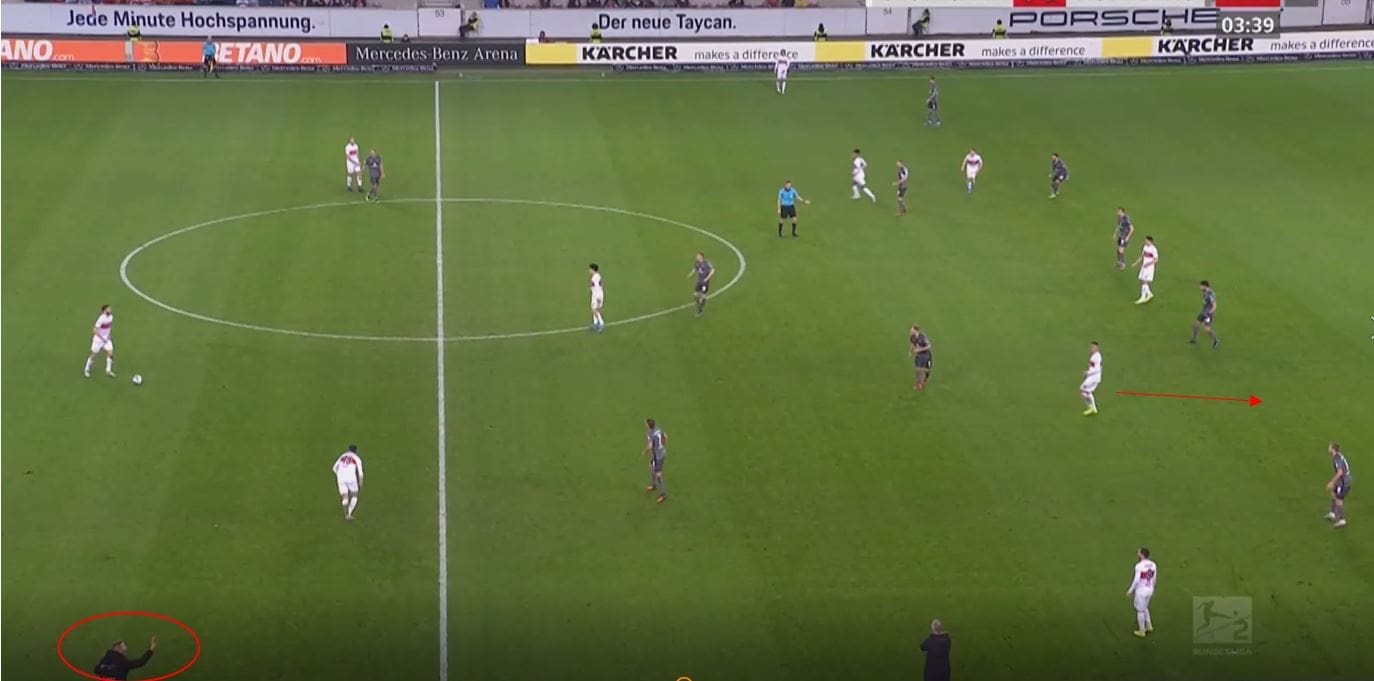

Although they play some really good football, Stuttgart are still inconsistent and Walter will surely make them better with time. Below is an example of an inconsistency in their game, where a midfielder drops where he is not in a position to receive the ball. Dropping would only force the marker on the wing to be attracted to him and push up slightly higher, which would damage the passing lane to that wide player. Walter recognises this situation, and as mentioned also likes his players to move into space rather than wait, and therefore instructs him to push back and then move deeper when the passing opportunity arises.

Conclusion

Stuttgart absolutely dominated the game and it’s hard to write much about Nuremberg’s approach other than them being deep and fairly compact. Stuttgart should have created more chances and would have if the quality was there, particularly from the centre backs, however, they will still be pleased with their performance overall. Nuremberg were limited to two real chances on the night, and scored from a poor mistake from Sosa, and struggled to create any chances due to their insistence on playing long passes whenever they received the ball, which played a massive part in them being limited to 25% possession. Tim Walter’s side remains fascinating to watch, and a match in which his side have 75% possession is just so much fun to analyse.

If you love tactical analysis, then you’ll love the digital magazines from totalfootballanalysis.com – a guaranteed 100+ pages of pure tactical analysis covering topics from the Premier League, Serie A, La Liga, Bundesliga and many, many more. Buy your copy of the December issue for just ₤4.99 here

Comments