International football is highly distinguishable from club football, not only because of the seldomness of matches but also due to the styles of play on show.

Where winning was once the only important factor behind success, with little care for eye-pleasing football, the demands of the modern game have brought significant change at club level.

Lifting silverware and winning matches are still vital for managers but it is not enough now just to win. Having an ever-present style is of utmost importance for teams when deciding which manager will take charge in a dugout for the foreseeable future.

This is primarily the case at the elite level, such as in the Premier League. Managers like Mauricio Pochettino and Graham Potter have been highly successful in England due to their distinct footballing philosophies as opposed to being notorious winners of trophies.

However, on the international stage, it’s quite the opposite. Success in competitions such as the World Cup and the European Championships leans heavily on a nation’s ability to be pragmatic.

Gareth Southgate has been the most successful England manager since Sir Alf Ramsey due to his ability to make the Three Lions flexible tactically and to approach games in a more conservative nature, particularly against better opposition. Essentially, on the international stage, if you don’t learn to bend then you will break.

International managers rely on being tough to break down before building patterns of play to score goals, which is ultimately the aim of football.

Often, there are far fewer risks taken from sides, especially in tournaments, with many managers opting to adopt a more defensive approach in matches. This is one of the reasons why many supporters have grown in contempt of international football, labelling it boring.

With the exception of Spain who have a very club-like feel to their overall game, nations at the World Cup have been highly cautious, with many coaches preferring to be the antagonists instead of the protagonists.

This tactical analysis piece will be an analysis of the defensive tactics used by managers at the FIFA World Cup. It will be a tactical theory piece, seeing what some of the common trends in defensive setups are so far at the tournament.

The Polish and Iranian approach

In their opening game of Group C at the World Cup, Czesław Michniewicz deployed some bold tactics in order to walk away with a vital point against a Mexico side hell-bent on ball retention under the tutelage of the former Barcelona boss Gerardo Martino.

The Polish side could’ve even walked away from the game with all three points had star man Robert Lewandowski tucked away his penalty which was saved by the Mexican legend Guillermo Ochoa.

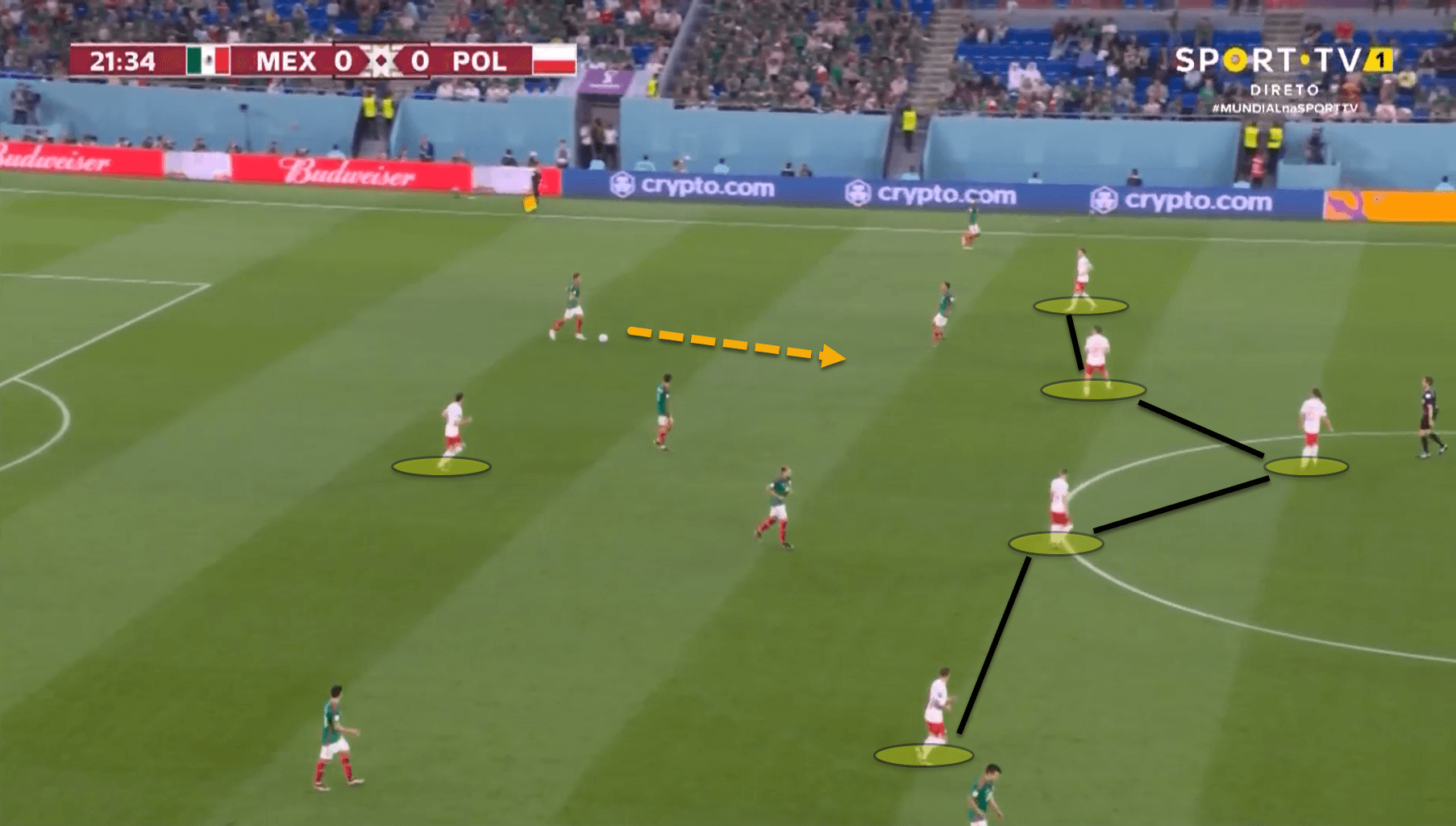

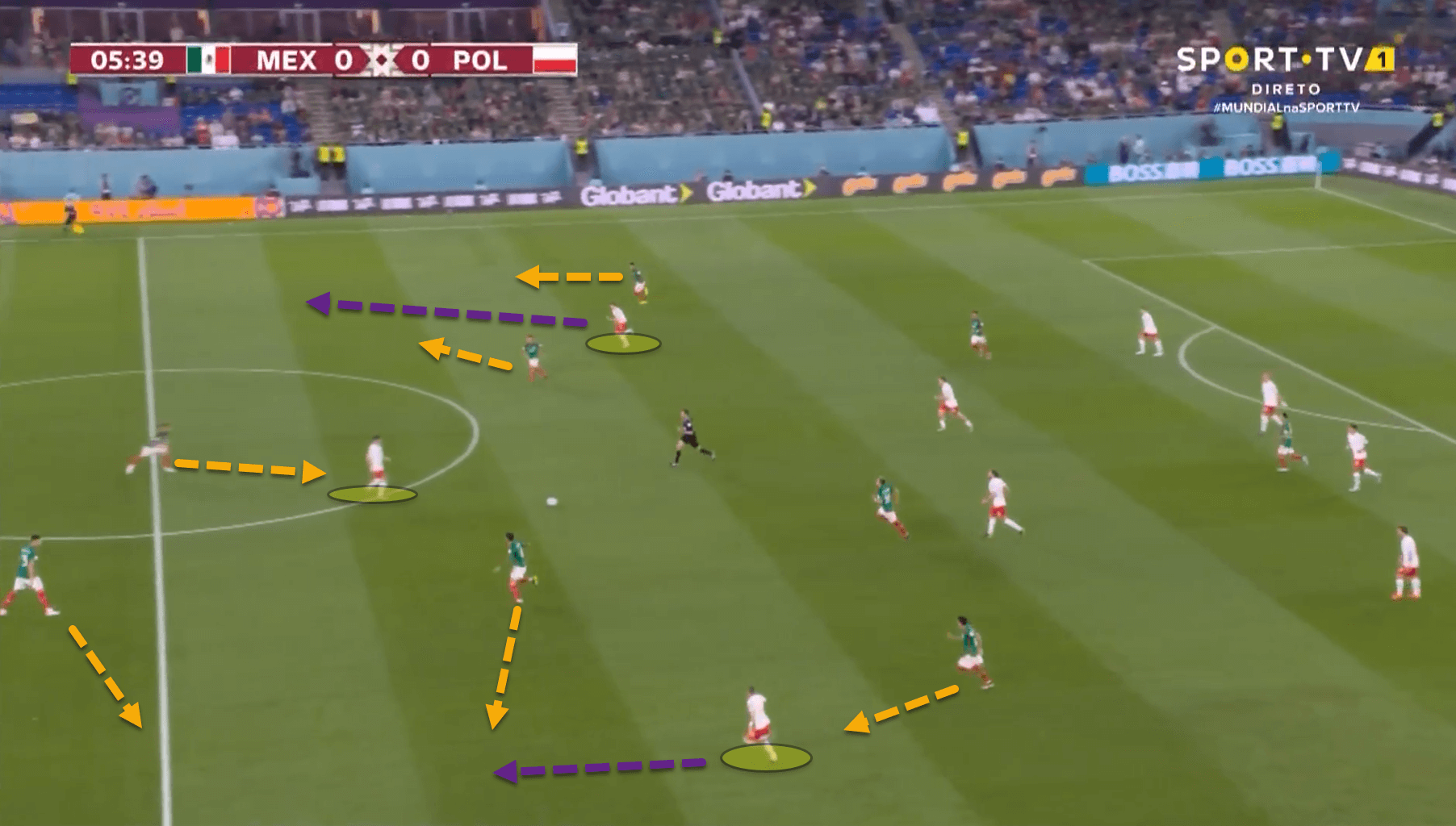

Michniewicz, from the get-go, ensured that his team were difficult to break down. The manager lined his players out in a 4-5-1 but Poland spent the majority of the match in a 6-3-1 low defensive block, bringing an incredibly conservative gameplan into the clash.

Mexico, on the other hand, set out in a 4-3-3, looking to build their way through the thirds of the pitch on the deck, using patient build-up in their own half.

Poland didn’t look to match their opponents in the build-up phase and so Mexico’s defenders could carry the ball deep into their own half relatively unscathed, with Michniewicz’s men opting to drop off into a 4-1-4-1 mid-block.

There was little to no pressure applied by Poland until Mexico stepped into the opposition’s half of the pitch.

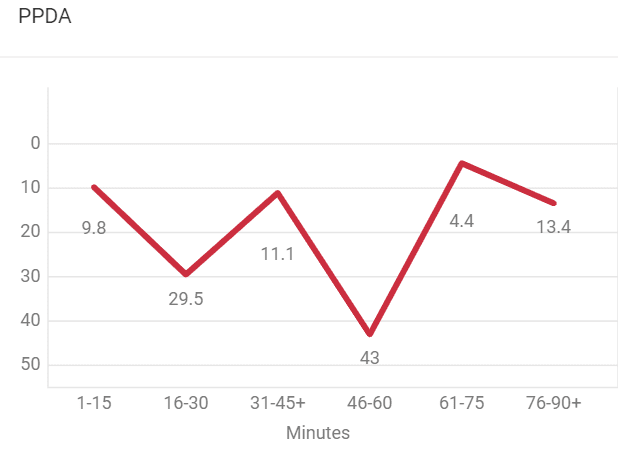

Due to this pragmatic approach, there were long spells of the match where Mexico could play 30 to 40 passes per possession without Poland making an attempt to win back the ball. This can be seen from Poland’s overall Passes allowed Per Defensive Action (PPDA) graph from the fixture.

As Mexico came deeper and deeper up the field of play, Poland dropped lower and lower into a highly defensive block.

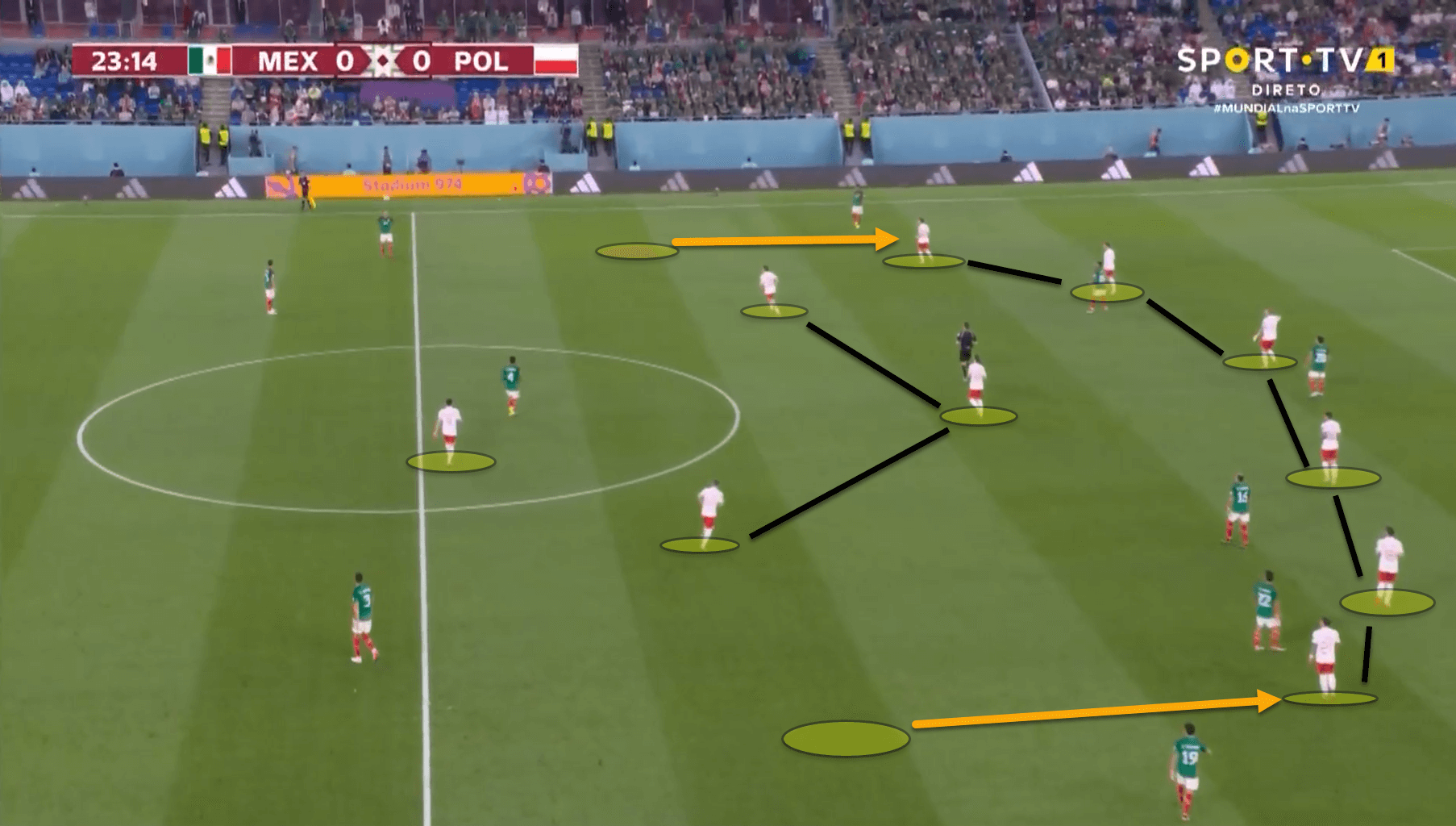

The wingers in the team’s 4-5-1 would drop into the backline to mark Mexico’s high fullbacks, creating a 6-3-1 for large parts of the game. In turn, the Polish fullbacks would narrow up alongside the two centre-backs in what created almost four central defenders.

Nicola Zalewski, a player who has been utilised quite heavily at AS Roma as a fullback and a wingback started on the left wing for Poland, showing that the manager preferred defensive nous over attacking flair in this game.

Poland limited Mexico to crosses which were easily cleared away by the backline as well as chipped balls in behind the backline, but the short distance between the defence and goalkeeper meant that these were incredibly difficult to pull off.

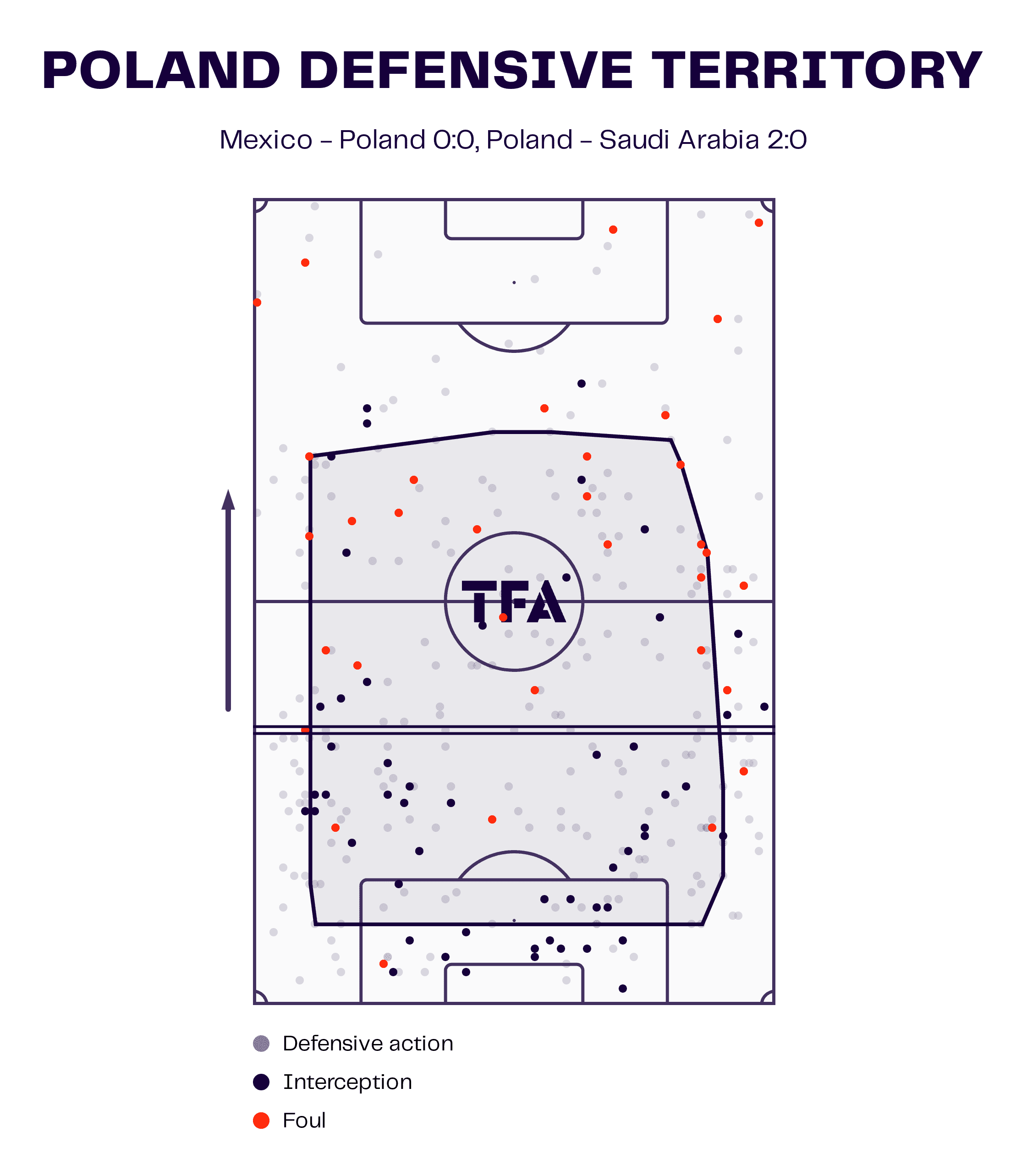

Furthermore, Poland’s average defensive line has been one of the lowest in the tournament so far. Michniewicz has drilled his players well out of possession and made them incredibly tough to carve open in the opening two matches.

The following image shows the average area of engagement from Poland as well as the average height of the defensive line across their opening two matches against Mexico and Saudi Arabia.

The approach did work in the first two matches as Poland kept two clean sheets. In the opening clash versus Mexico, Martino’s Latin American side accumulated an xG of just 0.87, with an average xG per shot ratio of 0.07 which is extremely low.

The Polish defence was much more permeable against Saudi Arabia, with Michniewicz changing the shape to a 4-4-1-1 as opposed to a 4-5-1. Despite winning 2-0, Herve Renard’s men missed a penalty and registered an overall xG of 1.9 excluding the penalty.

However, nine of Saudi Arabia’s strikes came outside the box which is a massive positive for Poland from a defensive standpoint.

The biggest issue for Poland in the first game was their lack of threat going forward. With the wingers pinned so far back as typical fullbacks, Lewandowski was isolated on his own up top.

Since Mexico pushed their fullbacks up, there was space for Poland to exploit on the flanks through counterattacks, but the low positioning of the wingers meant that getting forward in time was unrealistic.

Against Saudi Arabia, the manager played slightly more attack-minded, understanding the need for Poland to pick up three points and so Michniewicz put Arkadiusz Milik into the fold in place of a central midfielder.

This did work as Poland now had two frontmen on the pitch while their wingers would not defend as deep, allowing The Eagles to be far more dangerous in transition. Unfortunately, in the final group match against Argentina, Michniewicz reverted to the same gameplan as seen in the opening match as Poland were comfortably defeated 2-0, still going through on goal difference.

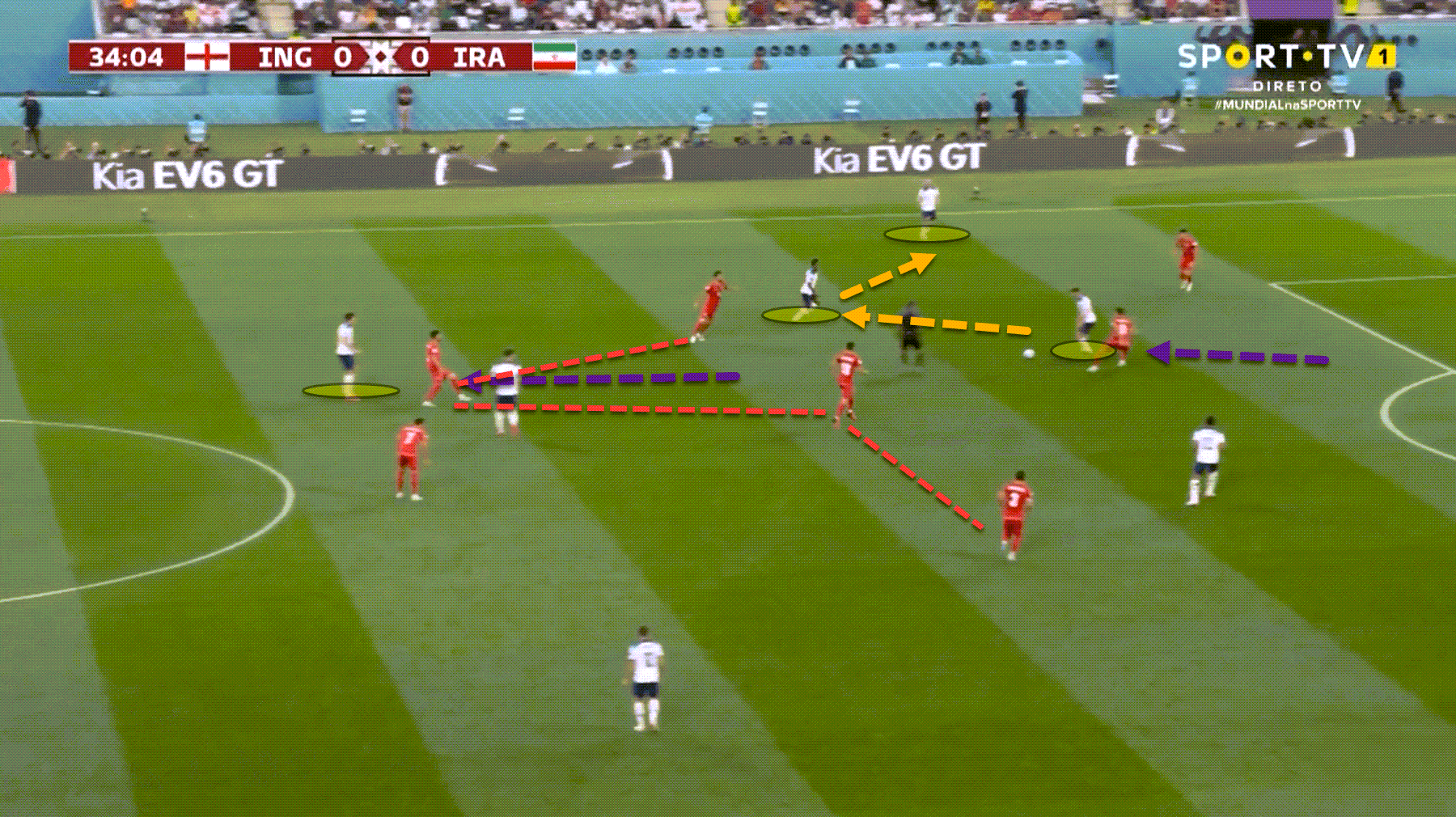

The only other team that have been remotely as conservative during games is Iran. Carlos Queiroz, a known pragmatist, deployed a rigid 5-4-1 low block against England in the opening game of Group B.

This backfired greatly. Not only did it hinder Team Melli’s defensive capabilities, but also left them with little threat going forward.

The main reason for this was the use of Mehdi Taremi as a lone centre-forward.

With defenders such as Harry Maguire and John Stones who are excellent at breaking the lines, Iran pressed with just one striker on the field, causing a numerical disadvantage against England’s two centre-backs.

This caused one of the Iranian midfielders to have to step out and help Taremi when applying pressure to the central defenders which left passing lanes open to England’s attacking players between the lines. The Three Lions’ first goal came from this exact situation, as shown above.

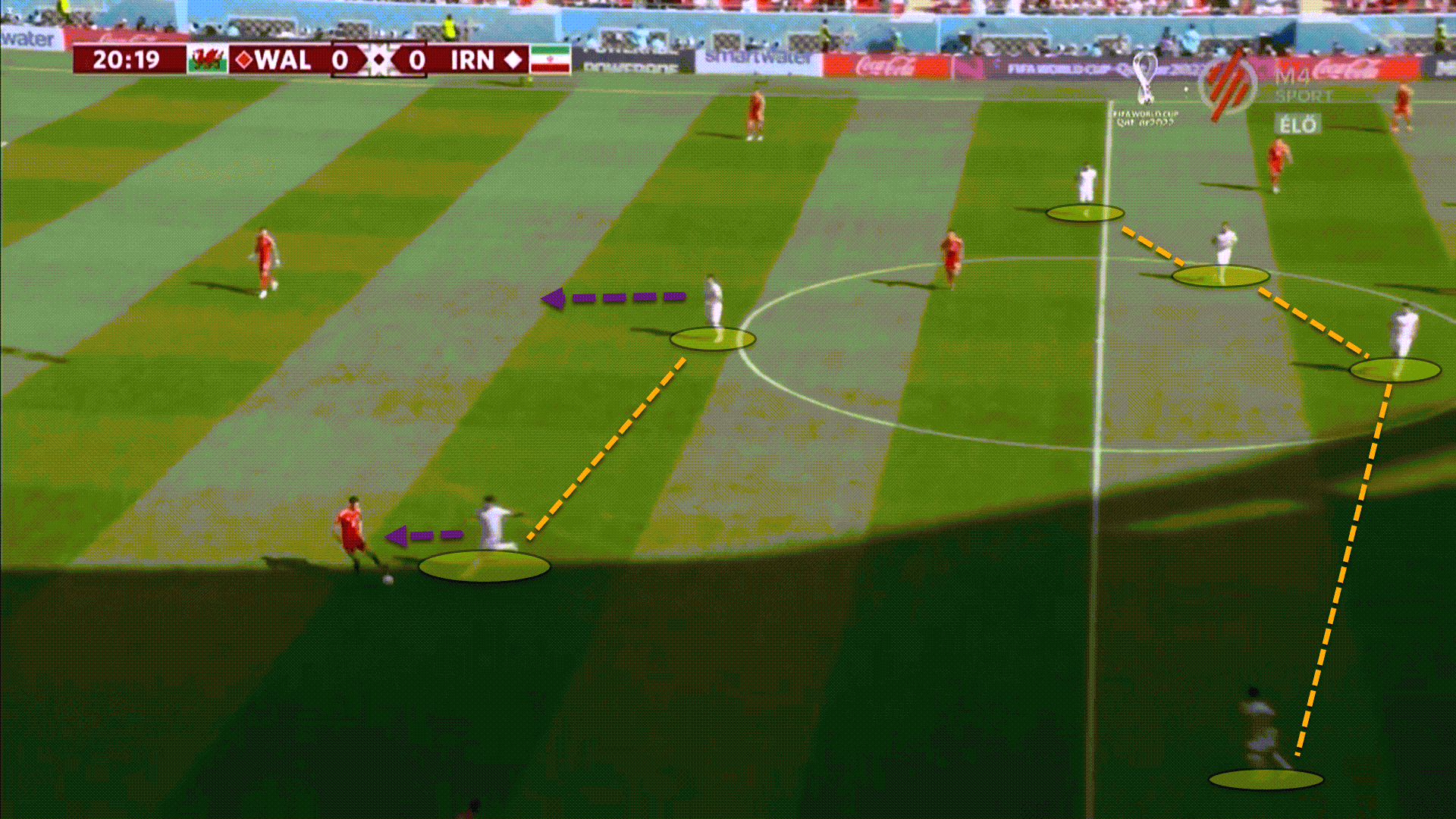

In Iran’s second match, needing a win, Queiroz rectified his error, switching to a 4-4-2. Iran still defended with a low block against Wales but having a two-man frontline from the get-go meant that one of the central midfielders didn’t need to step out to press and so could hold their positioning, cutting off passing lanes to players in front of the backline.

Furthermore, the two centre-forwards continuously used countermovements, meaning that one would drop off while the other ran into the channels during counterattacks, stretching Wales’ centre-backs who couldn’t cope with this movement.

Iran ended up winning 2-0, keeping a clean sheet and giving away an xG of just 0.7. Exactly half of Wales’ eight shots came from outside the area too, proving how difficult they found it to break down Iran’s low block.

Solid low-block defending has been very much alive during the 2022 World Cup in Qatar.

Rest defence and security rings

As the old football adage goes, attack is the best form of defence. We spoke about some of the best low-block defending at the World Cup so far. However, quite a lot of teams prefer to defend with the ball.

For instance, in Spain’s 7-0 thrashing of Costa Rica last week, Luis Enrique’s men didn’t concede a single shot, ending the match with an xG against of 0.00 while holding 78.4 percent of the ball.

La Roja defend by keeping possession. Where some teams prefer to cede the ball to their opponents and soak up pressure, like Poland and Iran, sides like Spanish maintain the mantra that if you have the ball, the opposition can’t cause any damage.

Nonetheless, possession-based football has evolved so much over the years. Now, the key to maintaining the ball and sustaining attacks is by having a solid rest defence structure.

Rest defence, or ‘rest attack’ as used by the USMNT manager Gregg Berhalter, is a term employed by coaches and analysts to describe how a team’s attacking setup allows them to recover the ball instantly upon losing possession, whether this is through counterpressing or having players situated close to the opposition’s attackers so that they can get tight as soon as the ball is turned over and win it back.

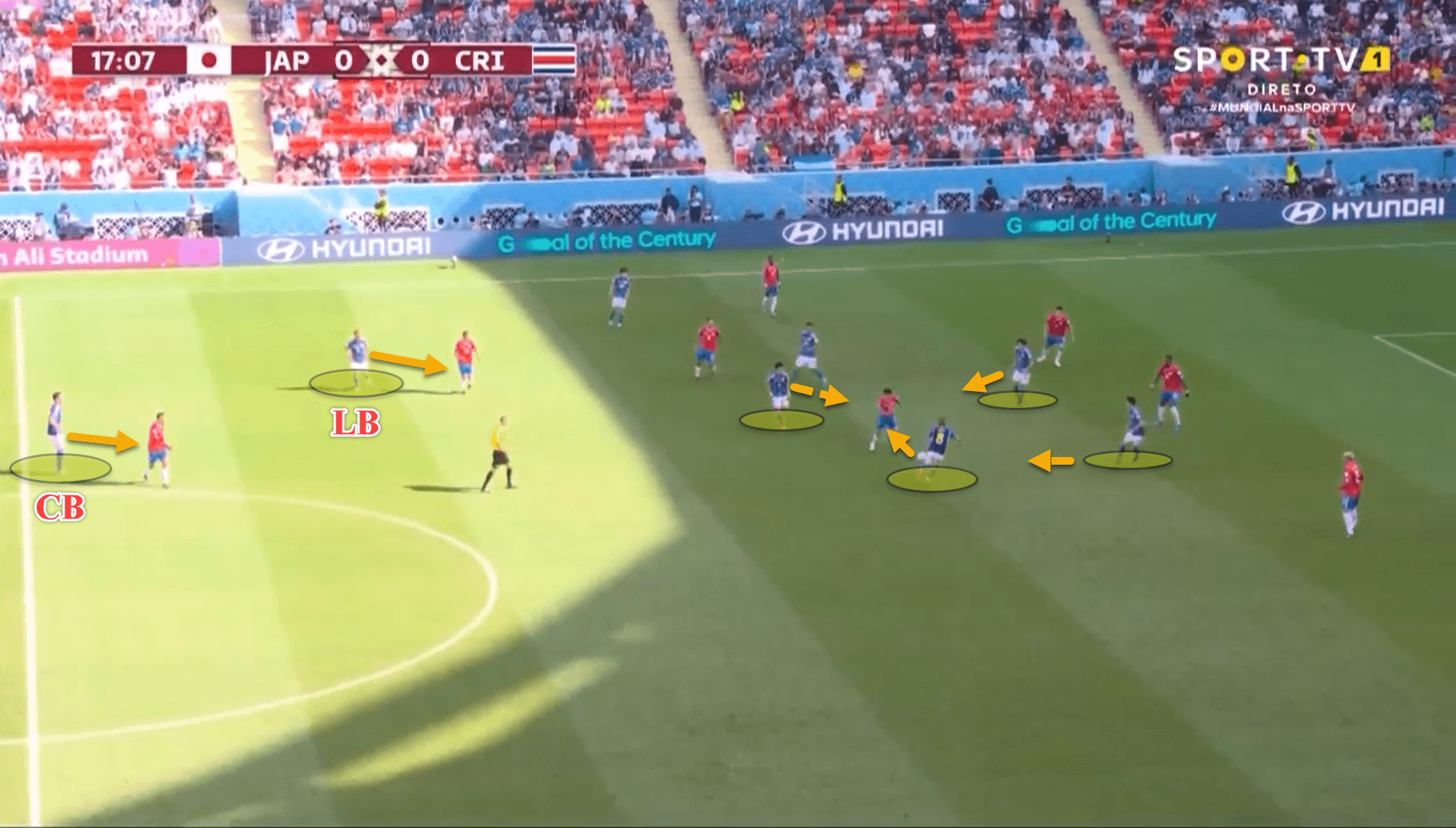

Japan deployed one of the best rest defence structures at the World Cup so far during their second-round clash with Costa Rica, even though Hajime Moriyasu’s men were defeated by one goal to nil.

The Japanese team struggled in possession but their efficiency during transitional moments has been a refreshing aspect of their tactical style.

When Japan lost possession against Costa Rica, they counterpressed aggressively to win it back and more often than not did. But just in case their initial counterpressing set-up was broken, the Asian side had a solid rest defence structure in place.

As shown in the previous image, when attacking, Japan kept their left back deeper alongside the two central defenders. Upon losing the ball, Moriyasu’s defenders stayed really tight to the Costa Rican forwards in case their counterpressing was broken further ahead.

This allowed Japan to stay tight to the opposition’s attacking players, preventing them from being able to receive the ball without getting marked which nullified Costa Rica’s threat in transition.

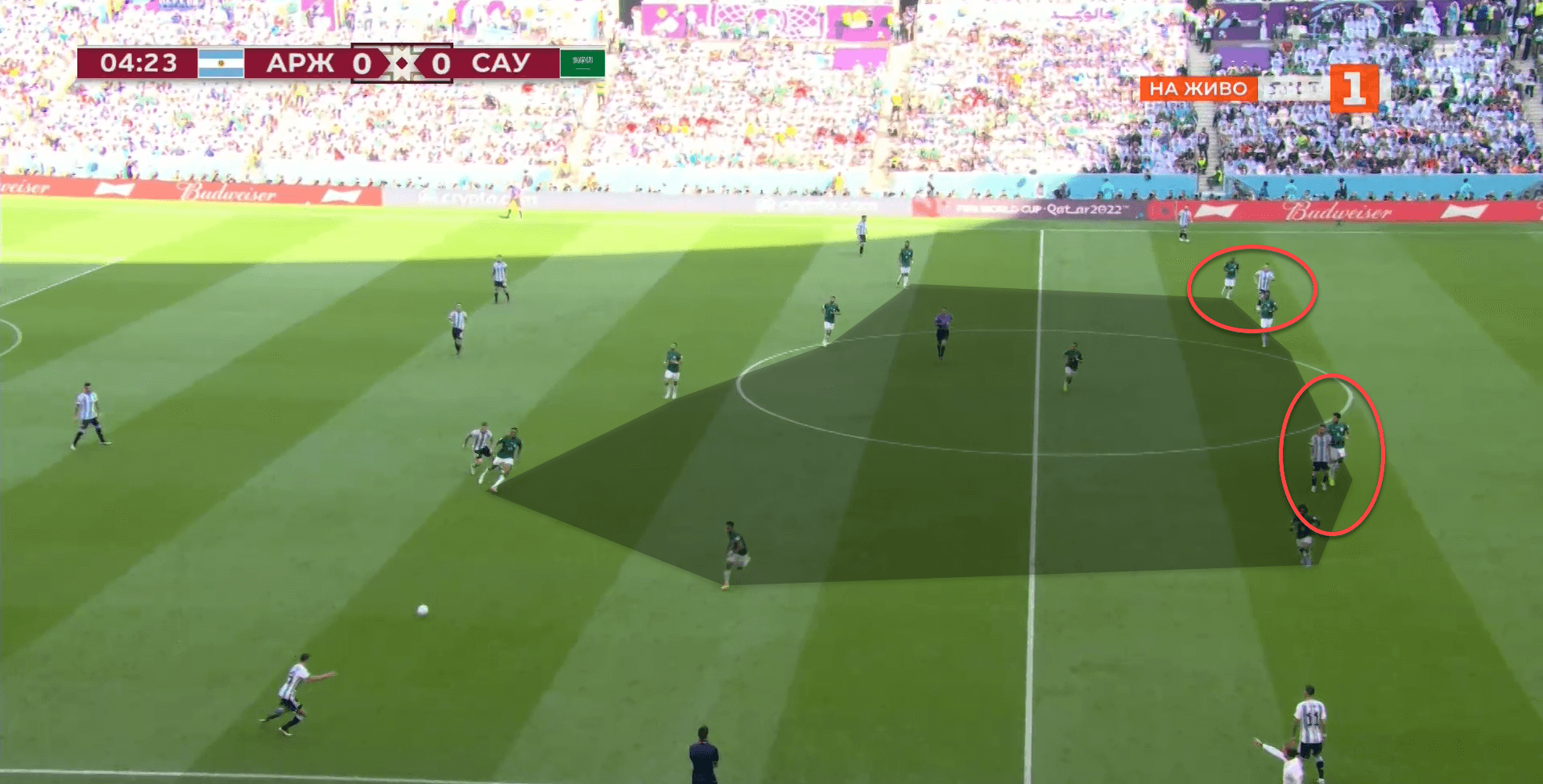

Quite often, teams create what is known as a ‘security ring’ in some circles. Essentially, this is where the players create a horseshoe shape in possession so that when the ball is turned over, the side will always have someone close to counterpress.

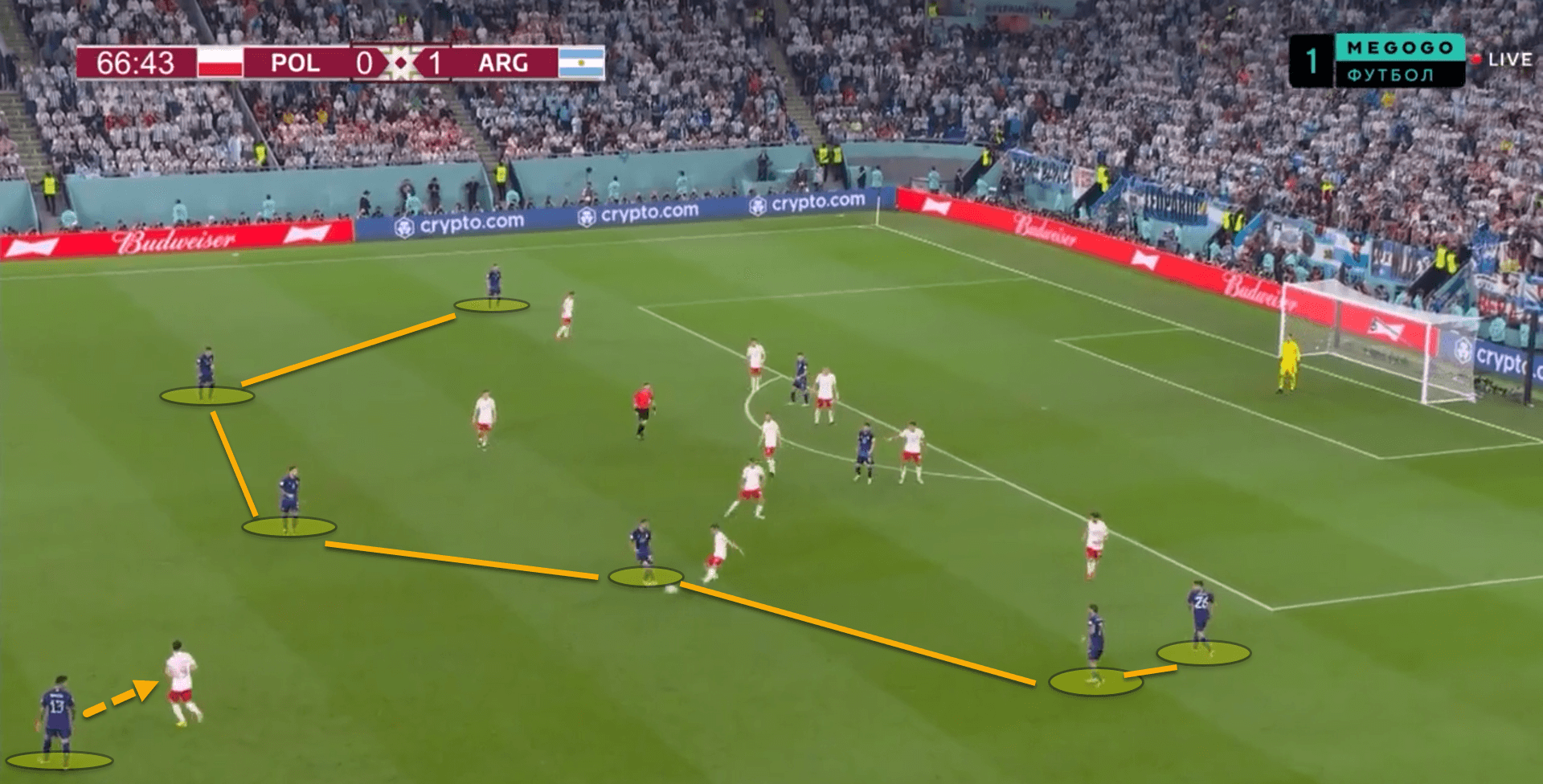

For example, here, Argentina have six players forming their security ring under the ball. If Poland were able to win it back, the nearest two or three players would all rush to the ball instantly to try and recover it once more.

Behind the security ring, the defenders are adding further safety by tightly marking the opposition’s centre-forward Lewandowski. This is a high-risk strategy still as managers are risking pushing their players well into the opponent’s half. If the security ring is broken, the backline will be exposed.

Nonetheless, using both a security ring and an air-tight rest defence structure behind it can make it extremely difficult for opponents to be able to break forward, particularly when looking to transition out of a deep defensive block.

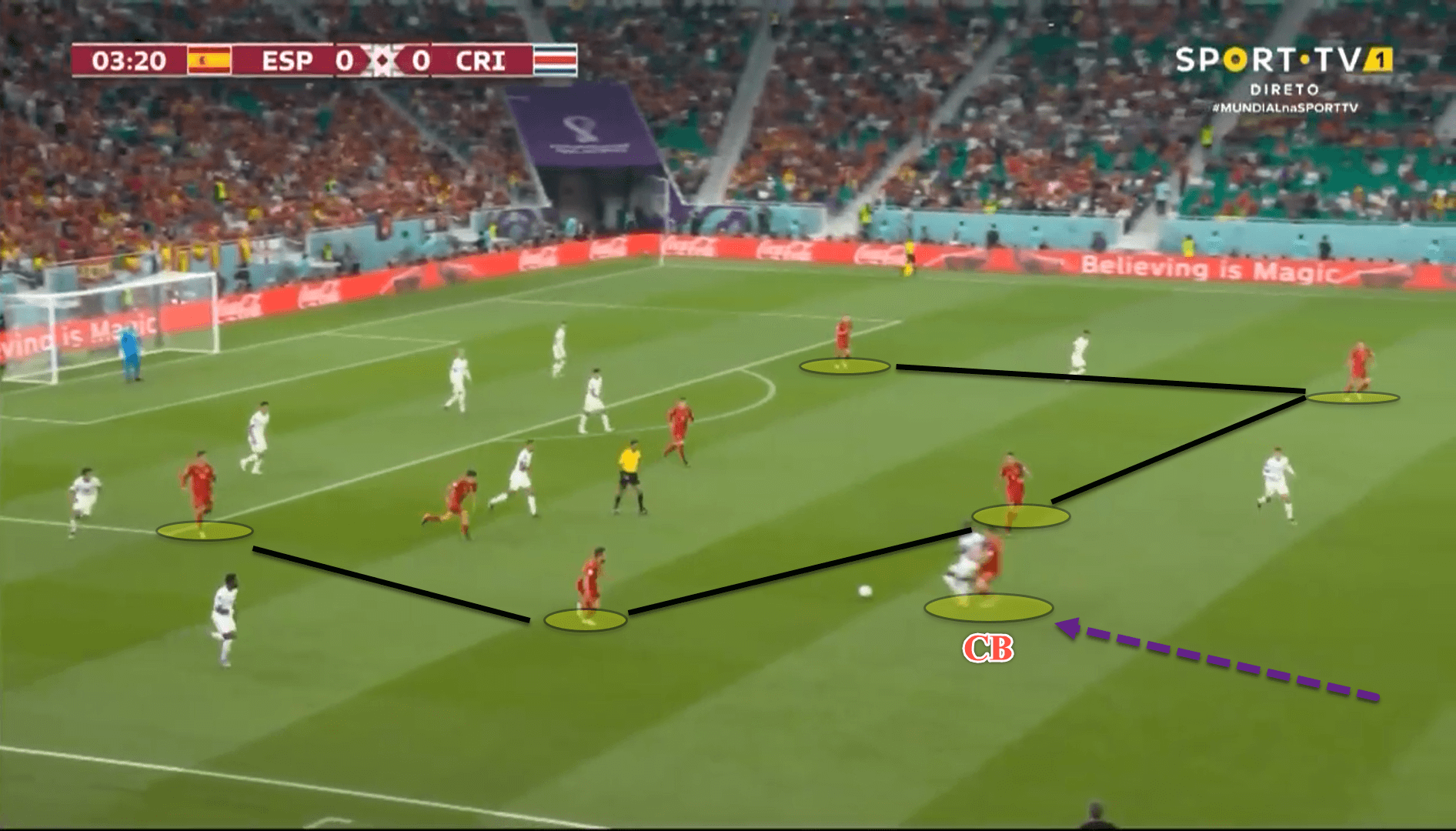

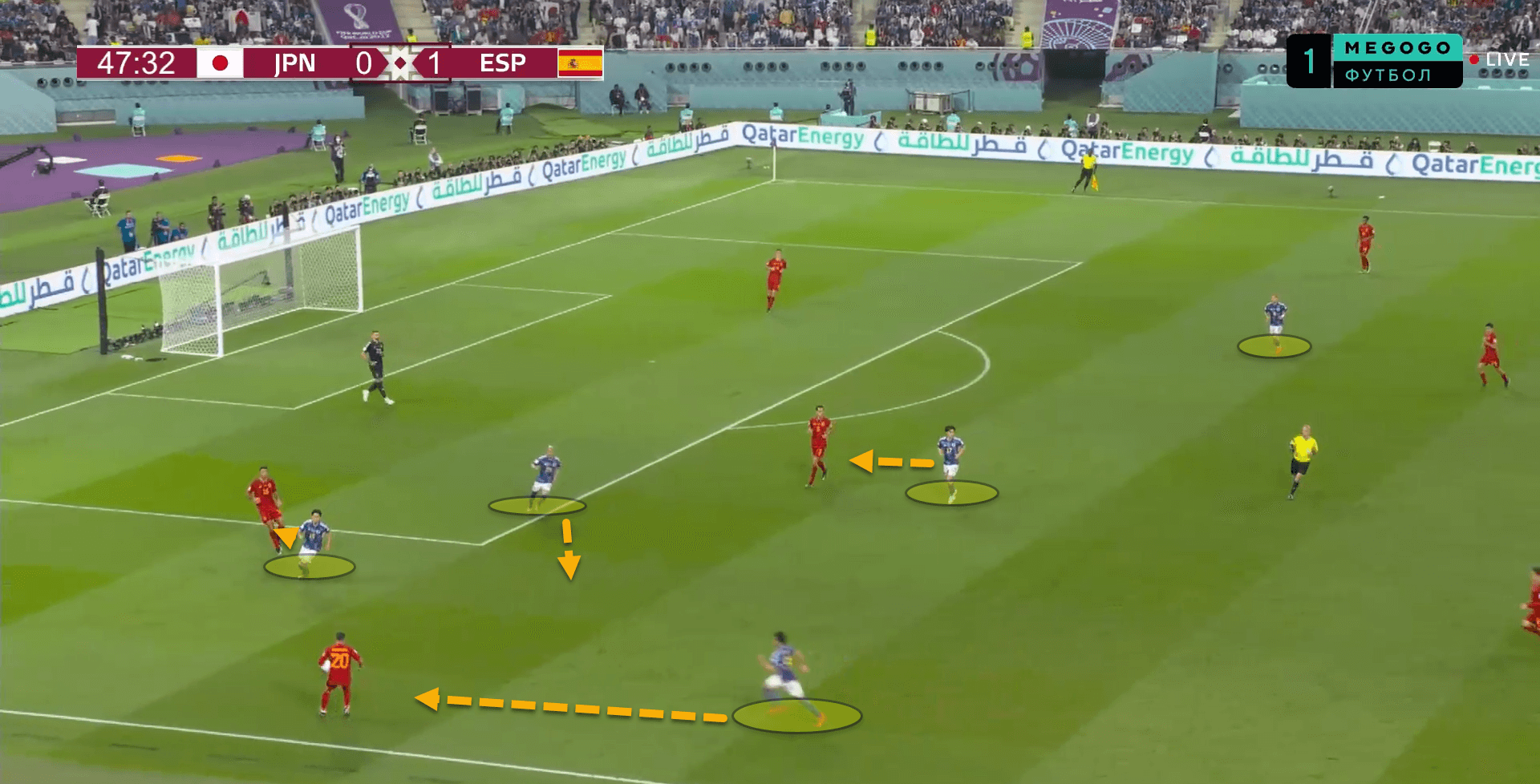

Spain have arguably been the most intense with their rest defence at the World Cup so far. La Roja’s security ring is extremely high up the pitch, practically in the final third in order to sustain attacks in this area, piling on pressure with each wave.

Behind this ring, Luis Enrique instructs his defenders to tightly mark the opposition’s attacking players who will be the most important in transition, even so far as following them into deeper areas which is certainly a high-risk, high-reward strategy, as shown in the above image.

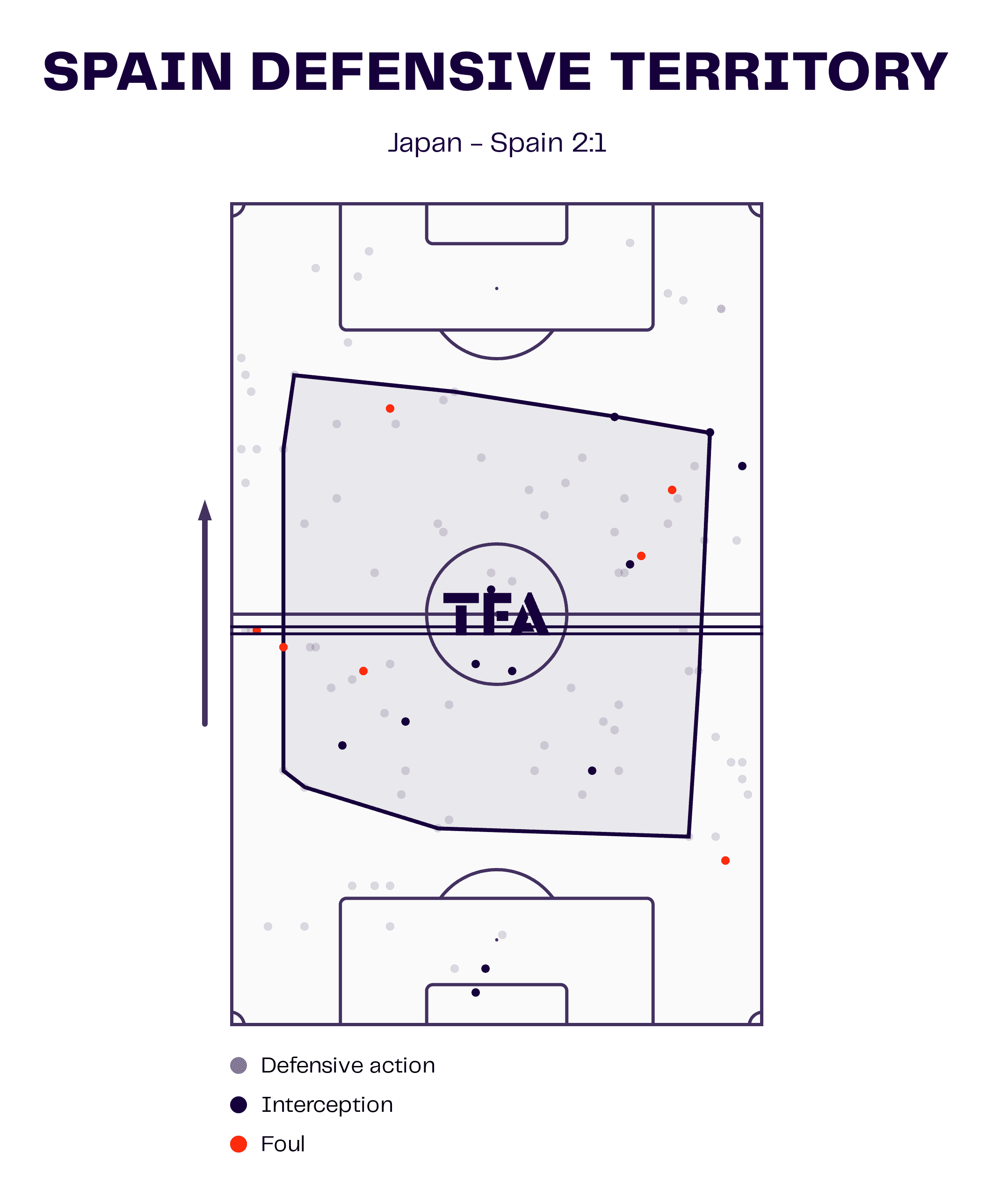

Spain’s incredibly high line during defensive situations can be seen from the team’s defensive territory map which plots the average defensive line height of the side as well as the average area of engagement.

As is evident from the data viz, Spain’s defensive line against Japan averaged out at the halfway line, which is the highest at the tournament so far across all nations, while the majority of the team’s defensive actions came into the opposition’s half of the pitch.

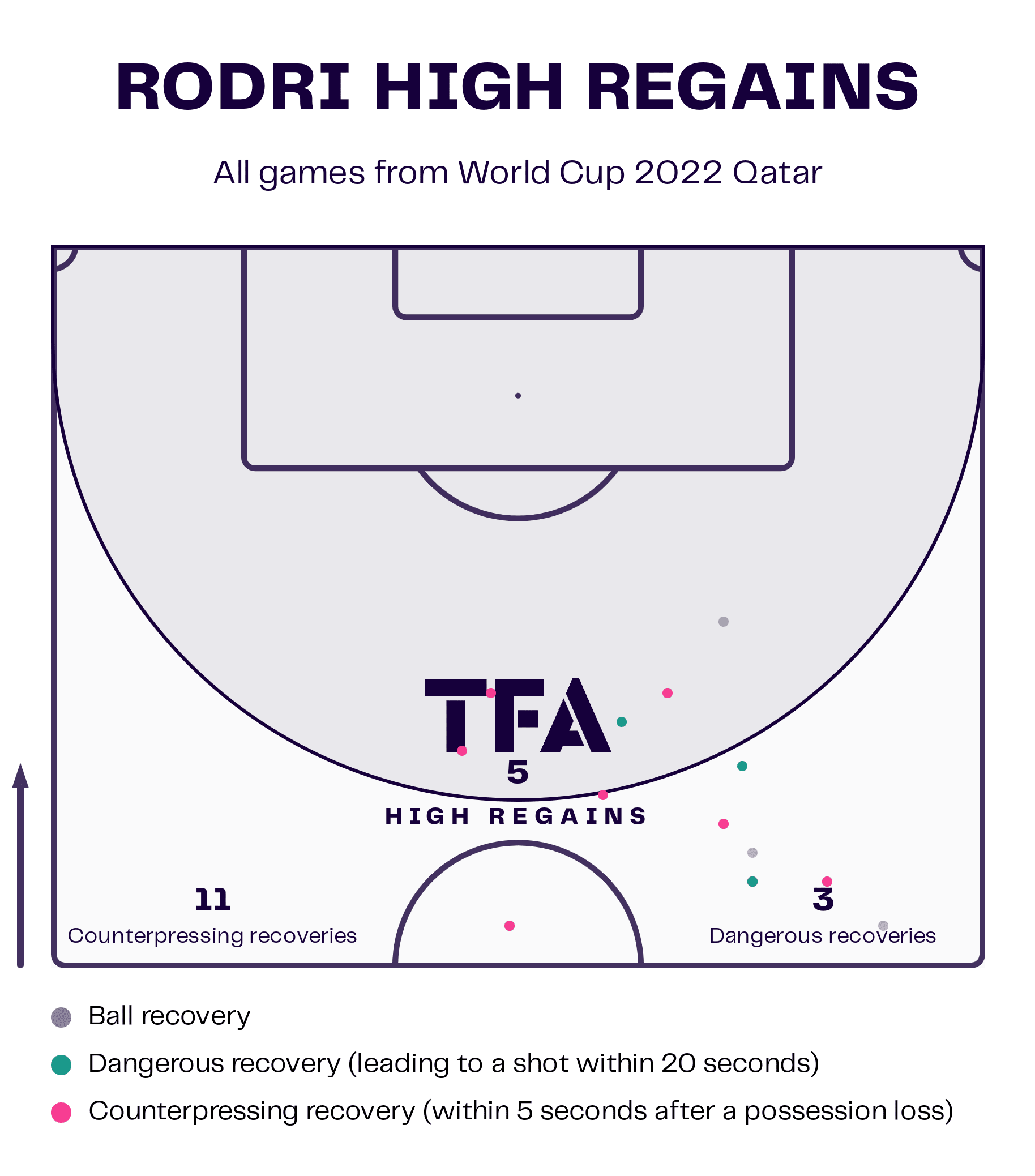

Furthermore, Rodri has played as a centre-back in all three of Spain’s games at the World Cup in the group phase. From the Manchester City man’s high regains map, we can see just how deep Enrique wants his central defenders to be positioned during rest defence so that they can help win the ball back as early as possible for the team.

Rodri has registered five high regains, 11 counterpressing recoveries and three dangerous recoveries, all coming in the final third.

Playing in such a manner involves possessing wonderfully-gifted and technical footballers but these same players must be willing to work hard out of possession, otherwise, it could spell disaster.

Mid-block pressing

One of the most utilised forms of defending as a unit at this World Cup has been in a mid-block, primarily in a 4-4-2 or a 4-5-1, although there have been outliers in this regard.

There are frailties at all levels of a defensive block. In a high block, if a team’s initial press is broken, it can leave the backline exposed further down the pitch while also causing there to be a wealth of space behind the defence that the opposition can play into.

In a low block, it can be difficult to form meaningful counters due to the sheer distance from goal and teams can be pinned down for long periods of time with wave after wave of attacks from opponents.

Low-block defending and quick transitions were a highly valued way of being solid at the back while scoring goals for many decades.

However, the development of complex rest defence structures such as security rings made this method less valuable as teams who are excellent at counterpressing can regain the ball with ease before the counterattacking side have even gotten out of their own third.

Mid-block defending offers the perfect balance for sides who want to stay compact and deny the opposition space between the lines but also want to be close enough to the goal so as to be effective in transition.

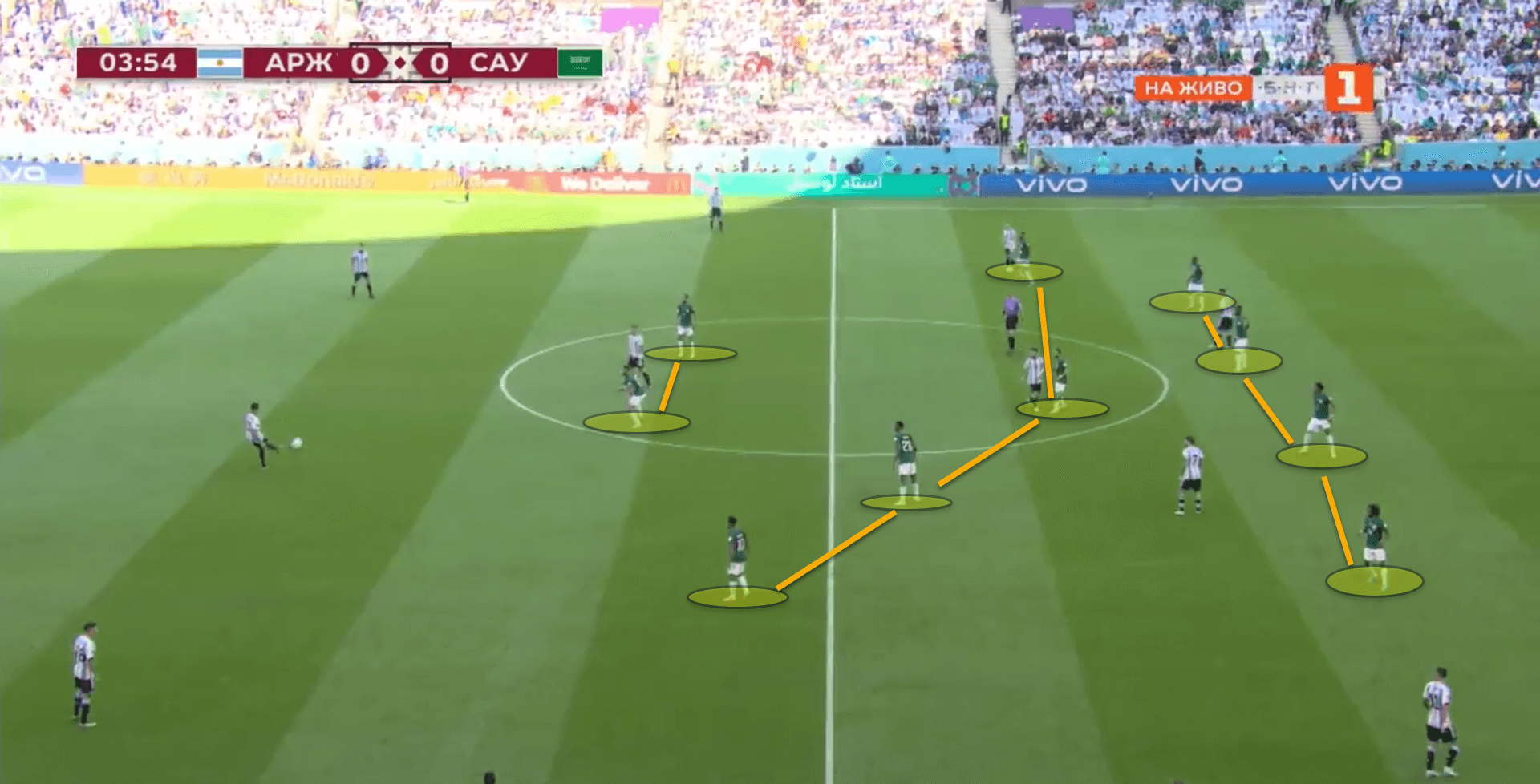

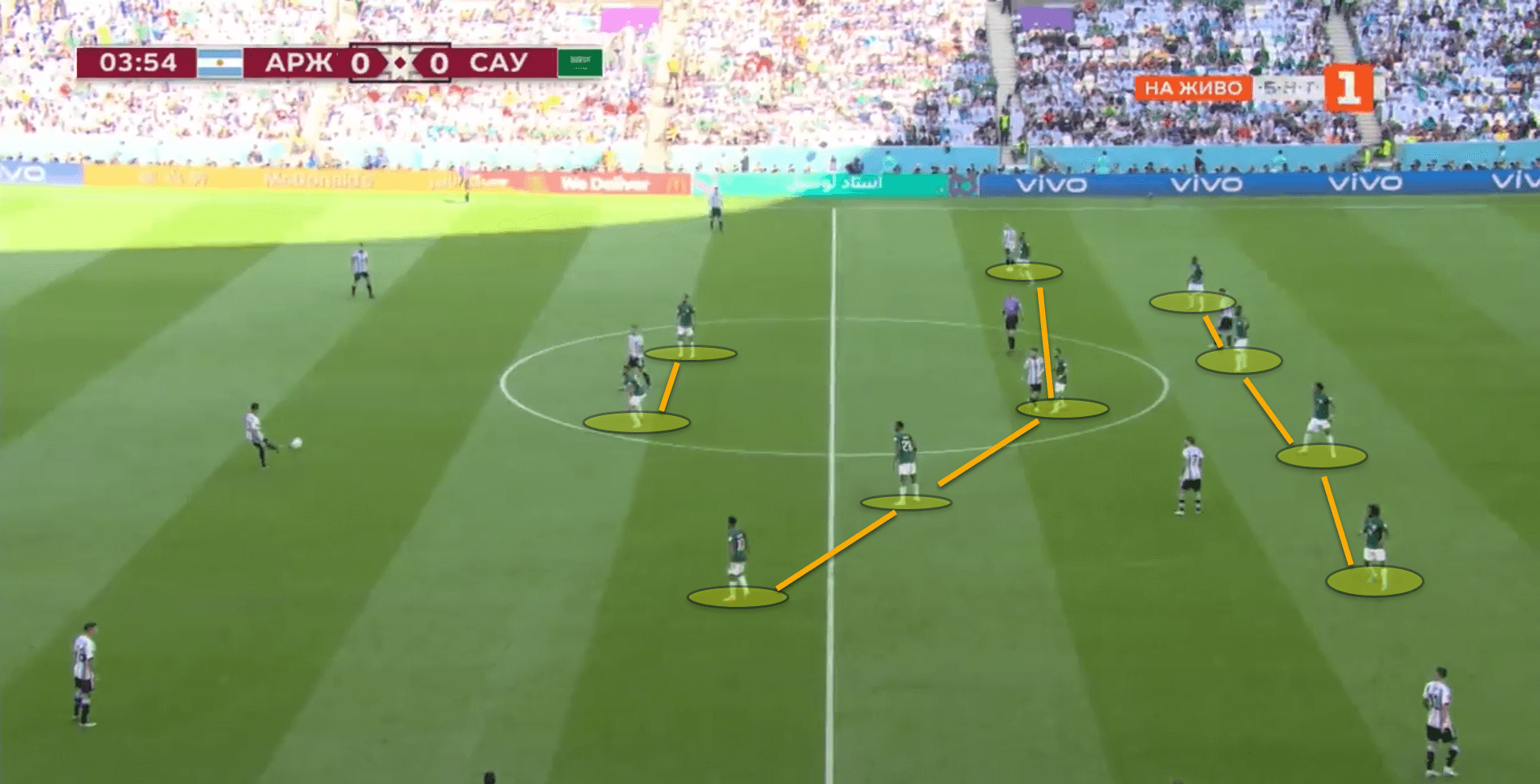

Here is an example of a well-drilled mid-block. Saudi Arabia were incredibly brave against Argentina by using such a high line which paid dividends in the end as Hervé Renard’s side walked away with all three points.

Renard deployed a 4-4-2 out of possession. The objective for the Saudi players was to constantly block the Argentine backline’s access to their attacking players who were situated between the lines throughout the block.

The Middle Eastern nation did this almost impeccably throughout the match. From just a few minutes into the game, it was clear that Argentina had been taken aback by the tactics used by their opponents.

Argentina proceeded to play into Saudi Arabia’s hands as players were dropping deep and pushing out wide to receive, leaving just two inside the defensive block, meaning nobody was being pinned down and there were no progressive passing options for the South Americans either.

An astute and coordinated mid-block can be extremely difficult for possession-oriented teams to play against. These sides excel when attacking players can receive between the lines.

However, a solid mid-block can deny this possibility, tempting teams to play balls over the top into the space beyond the backline. Argentina had to change how they typically play by lofting more balls over the top. Lionel Scaloni’s men looked really uncomfortable playing in this manner.

Mid-blocks also provide the defending team with the perfect opportunity to create decent exchanges in the level of the block.

Essentially, a medium-level defensive block is halfway between a high press and a low block. As such, it can turn into both relatively easily, with the players either dropping lower on the pitch or else stepping up to press.

At the 2022 World Cup, quite a lot of nations have used mid-blocks as a way to initiate a high press, waiting for a backwards pass to be made before aggressively closing down the ball carrier and the nearest passing options.

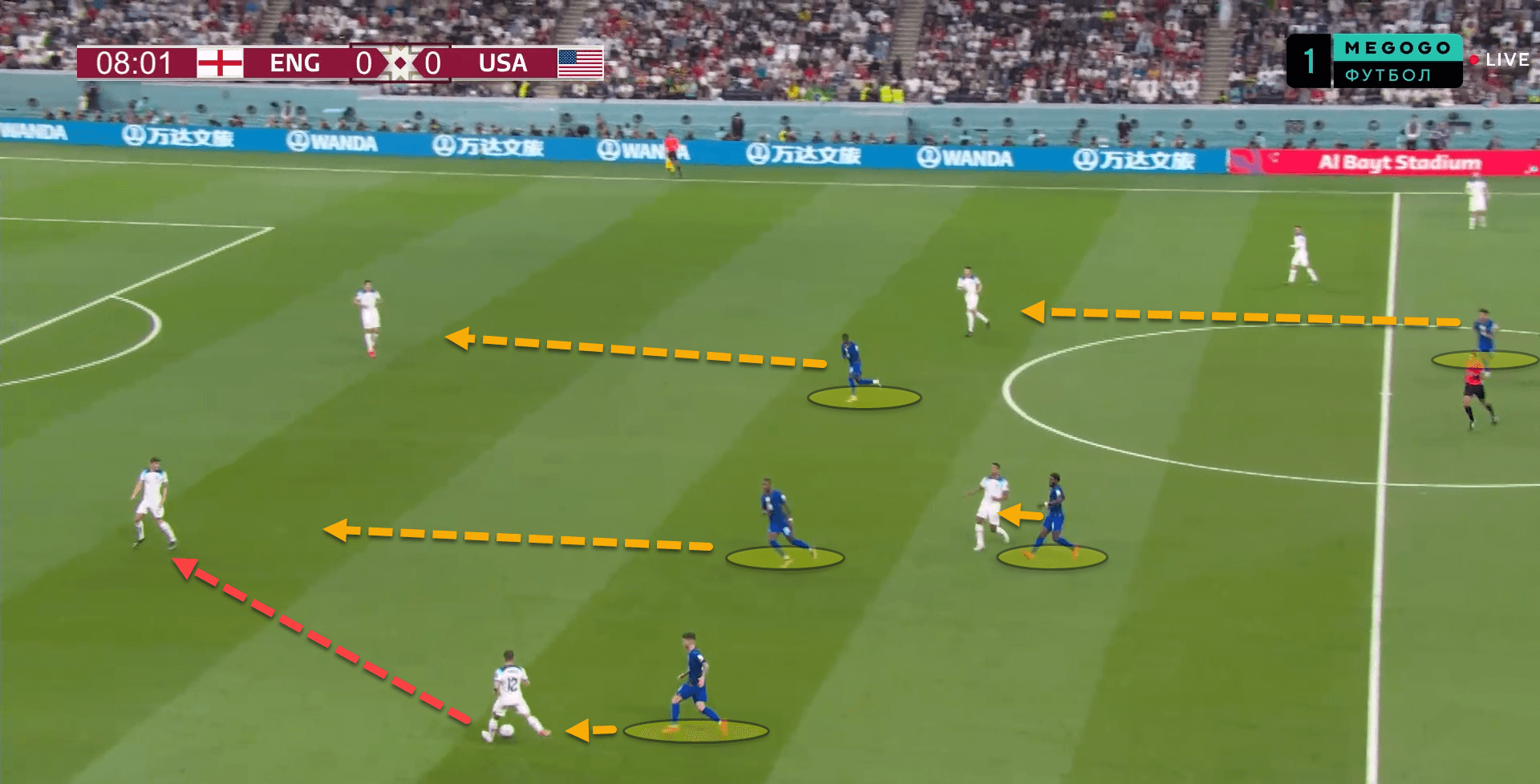

In this image, the USA were being rather passive in a 4-4-2 defensive mid-block. England’s right-back Kieran Trippier squared the ball to centre-back John Stones.

Once this pass was made, it triggered the Americans to step up and exchange their mid-block for a high press, with the two centre-forwards leading the charge by closing down the centre-backs while the midfielders supported behind them.

An exchange from a mid-to-high block was exactly how Japan forced Spain into making an error when trying to play out from pressure during the nation’s ground-breaking 2-1 victory on Thursday.

Spain played a backwards pass to the goalkeeper Unai Simon which triggered Japan to push their block higher and press the 2010 champions, marking individuals man-for-man as players were stepping up with aggression and tenacity.

Spain didn’t cope with the block exchange and Japan won the ball back while pressing their opponents in the final third. Eventually, Ritsu Doan latched onto a loose ball and smashed it past Simon to equalise.

Japan have been the most consistent and effective in their use of a mid-block throughout the course of the tournament, although England, the USA, Saudi Arabia against Argentina, Morocco and Portugal have all proven useful when exchanging from a mid-block to one that is higher and lower on the pitch.

Conclusion

Just like there’s no one way to attack, there’s certainly not one way to defend. Defending is an art and art comes in many different forms.

Some managers prefer to protect their own goal to prevent shots against them while others take risks to be proactive, turning the defensive phases into goalscoring opportunities.

Most sides are a blend in between the two but the World Cup has provided a plethora of different defensive styles so far which has been a joy to behold.

Comments