A season from hell is ticking closer towards the end for fans of Wigan Athletic.

Having been culpable of not paying players in four instances over the past 11 months, the Latics were deducted three points by the English Football League. While three points doesn’t seem like much of a deadly punishment, it kicked the club further down the ladder after desperately trying to climb up over the course of the campaign.

Nine months after the season commenced, the Lancashire club have seen three different men sit in the dugout at the DW Stadium, none of whom were able to prevent the ship from sinking. Sitting rock bottom of England’s second tier right now, relegation is all but inevitable and results seem irreversible.

Leam Richardson, who guided Wigan Athletic to promotion last season, was the first victim to be shown the door but there was brief hope when former Arsenal, Manchester City and Liverpool defender Kolo Touré took the reins. Unfortunately, that hope was short-lived. The Ivorian followed in Richardson’s footsteps less than two months later.

Now, former player Shaun Maloney has been tasked with seeing the season out. The Scot was the man who took the Latics down, but the blame can’t be solely pinned on him.

While off-the-field issues played their part in what was an utterly disastrous campaign — and could have been the main cause of poor displays — none of the three head coaches could ever get a grip on the team from a tactical perspective.

In this tactical analysis piece, we will dissect Wigan’s catastrophic campaign, looking at the tactics used by each manager to understand where things went horribly wrong for the team on the 10th anniversary of their FA Cup win under Roberto Martínez. Time moves quickly, doesn’t it?

Leam Richardson

Richardson’s first two seasons at Wigan Athletic were filled with success. Having taken over as caretaker boss in the 2020/21 campaign following the dismissal of Paul Cook, the young coach managed to steer the Latics to safety in League One, avoiding a catastrophic fall to League Two which could have been detrimental to the financial stature of the club at the time, although this demon caught up eventually.

Nonetheless, 12 months later, Richardson steered Wigan back to the Championship, finishing top of League One and earning himself the Manager of the Season award. It was a phenomenal achievement given the state of the club just a season prior.

However, keeping them in the second tier was going to be a difficult task due to the financial disparity among clubs in the EFL Championship.

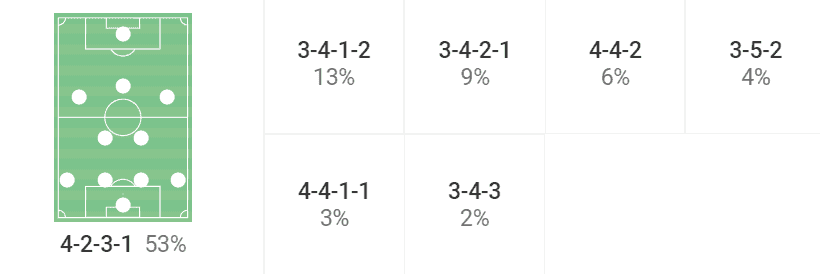

Last season, Richardson preferred to set his team up in a 4-2-3-1 formation which saw the Latics cruise near the top of the table. Nevertheless, in the last 12 matches of the 2021/22 campaign, Wigan switched to variations of a back three — the 3-1-4-2, the 3-4-1-2, and even the 3-4-2-1 on one occasion. From these 12 matches, Wigan won just five and limped to the end in first place in what was a very close title race with Rotherham and MK Dons.

From the start of the 2022/23 season, Richardson stuck with his guns, keeping the back three in place. Logically, having an extra man at the back could have helped Wigan in a more difficult division, although the decision to permanently change to a back three last season seemed a little peculiar from the outside looking in.

Richardson preferred having three aggressive centre-backs, with wing-backs holding the width on the flanks who would push high in and even out of possession.

The ex-full-back opted for a two-man strike partnership as well, although normally Callum Lang would sit just behind Will Keane who acted as the primary number ‘9’. Sometimes, the formation could even look like a 3-5-1-1. This reared its head again later in the season under Maloney.

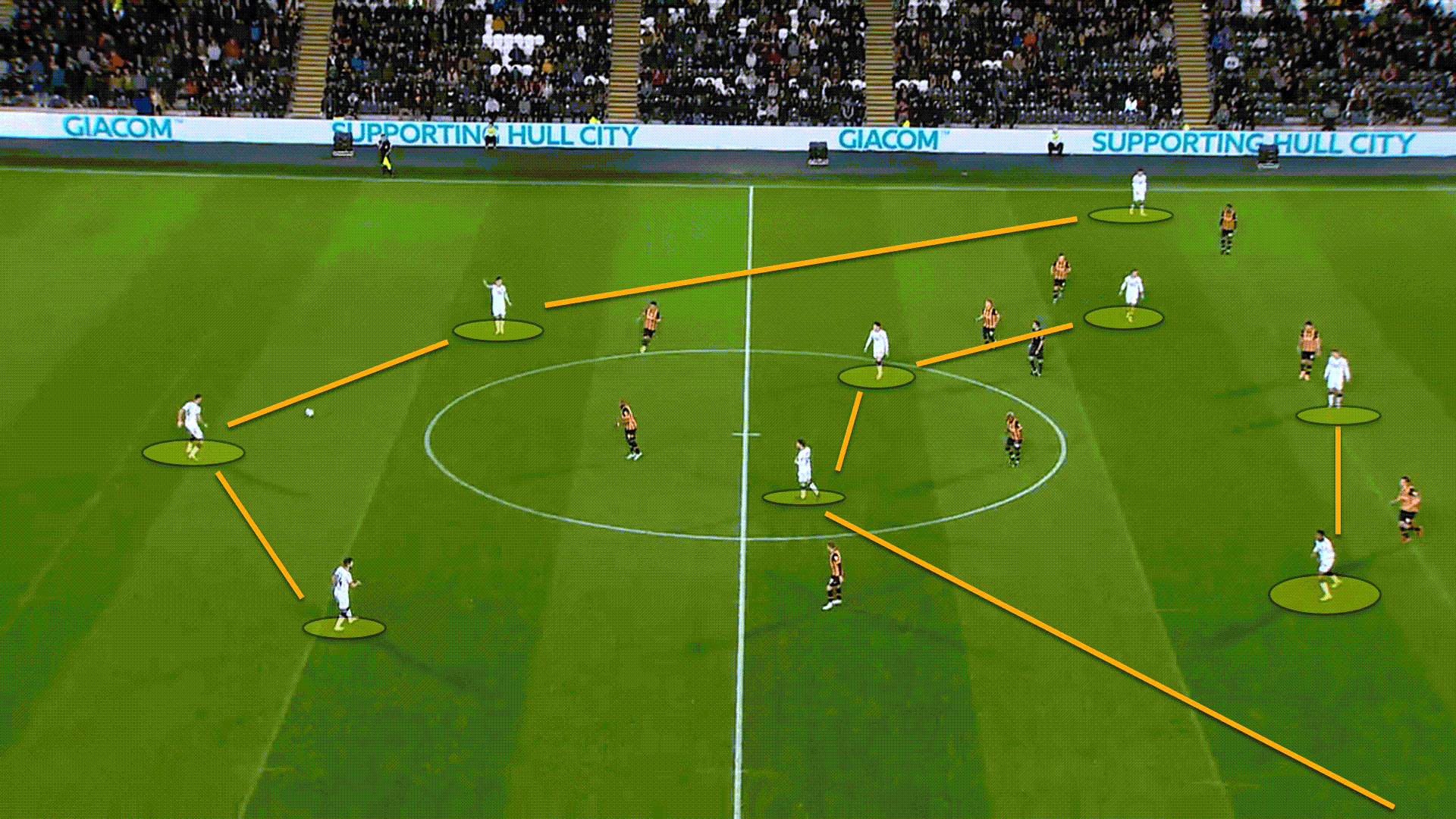

One of the key principles of Wigan under Richardson was the high press. Richardson always set up his team to press in a man-oriented fashion. Having three men in the middle was perfect for this because it meant they rarely ever had an underload in the midfield and could always match their opponents man-for-man.

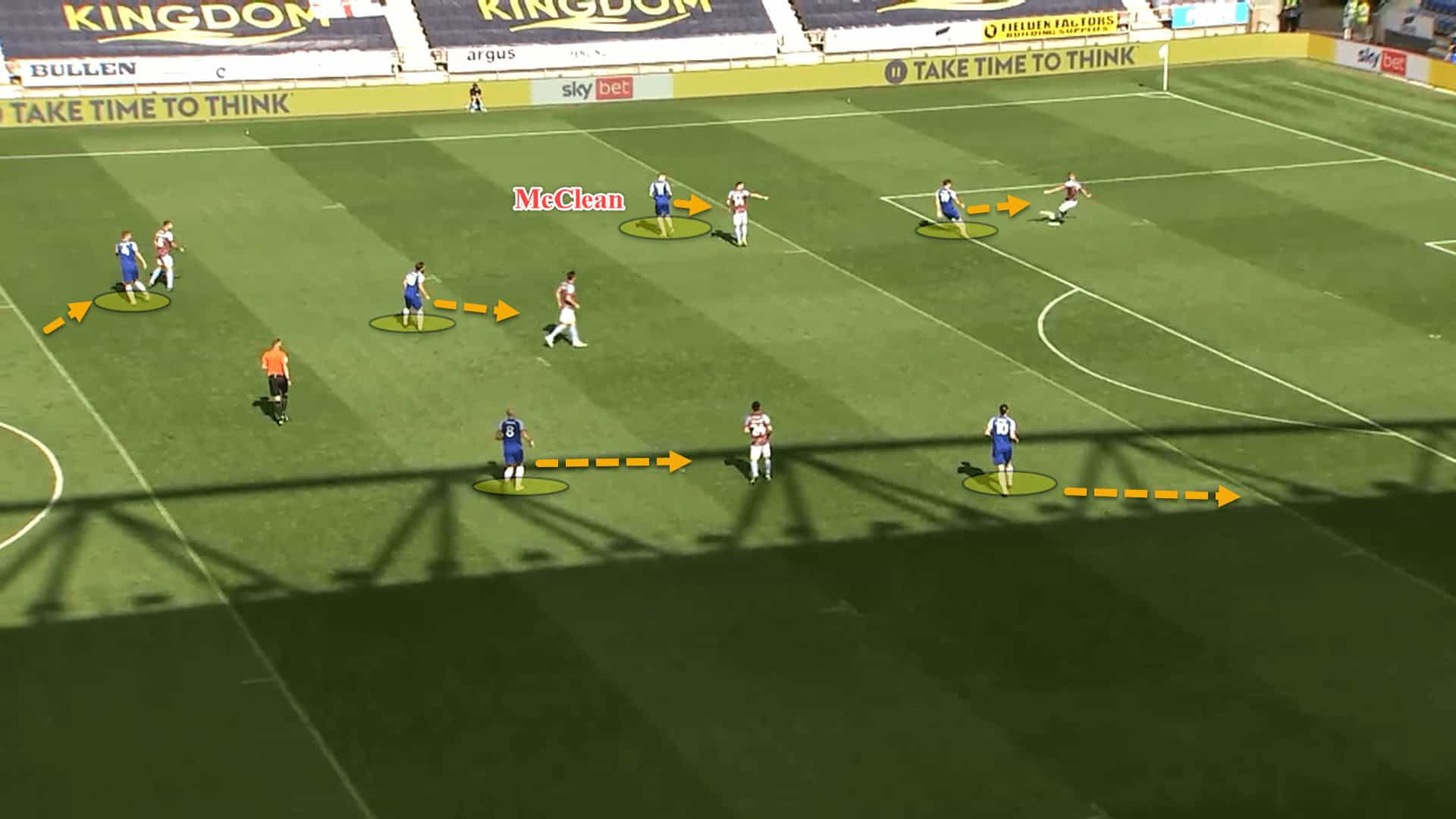

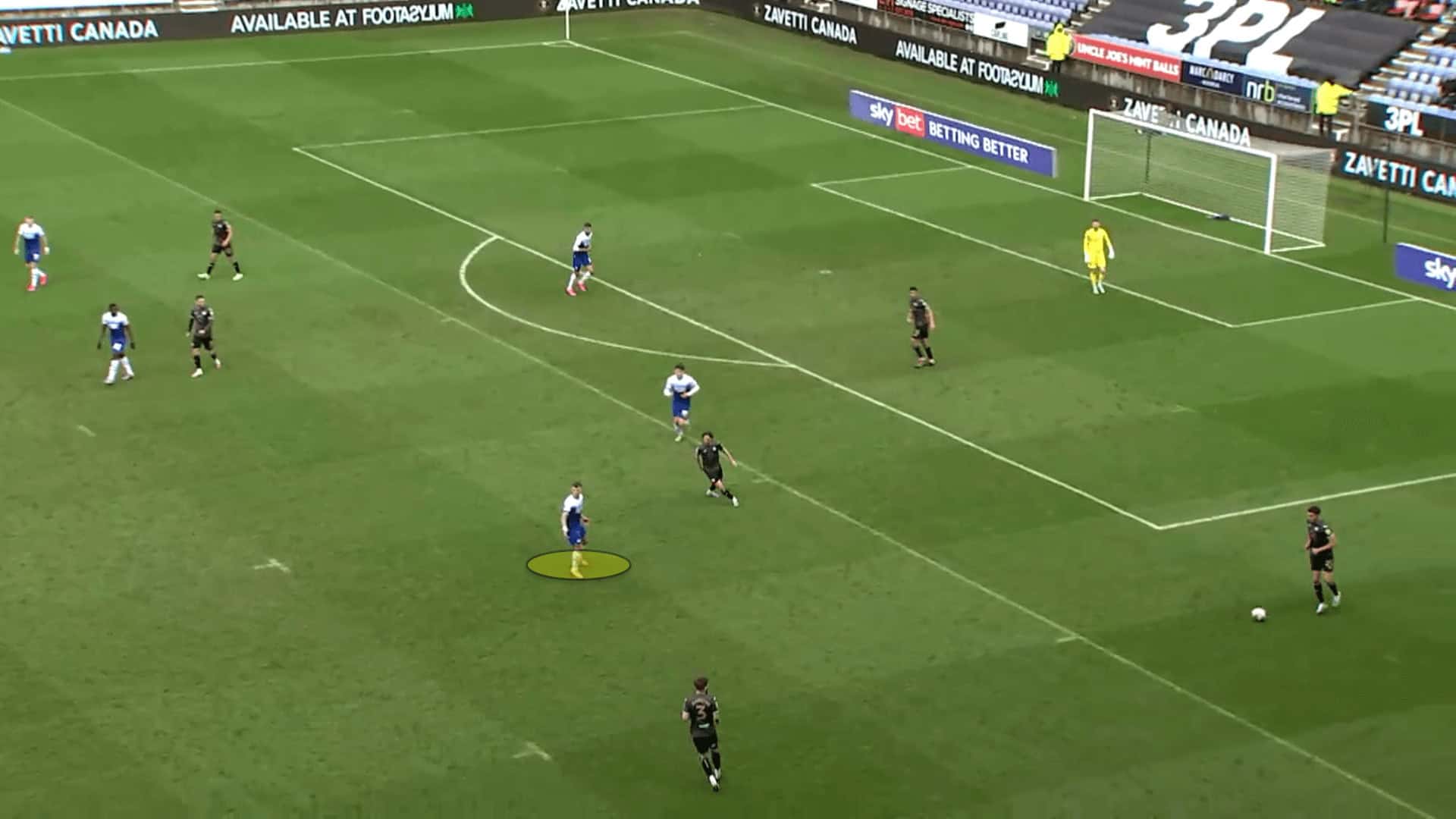

Here is an example of this man-oriented high block against Burnley’s 4-3-3. Even when Burnley’s right-back Connor Roberts tucked inside, left-wing-back James McClean followed him while Wigan pressed 3v3 against the Clarets’ midfield and 2v2 versus their centre-backs.

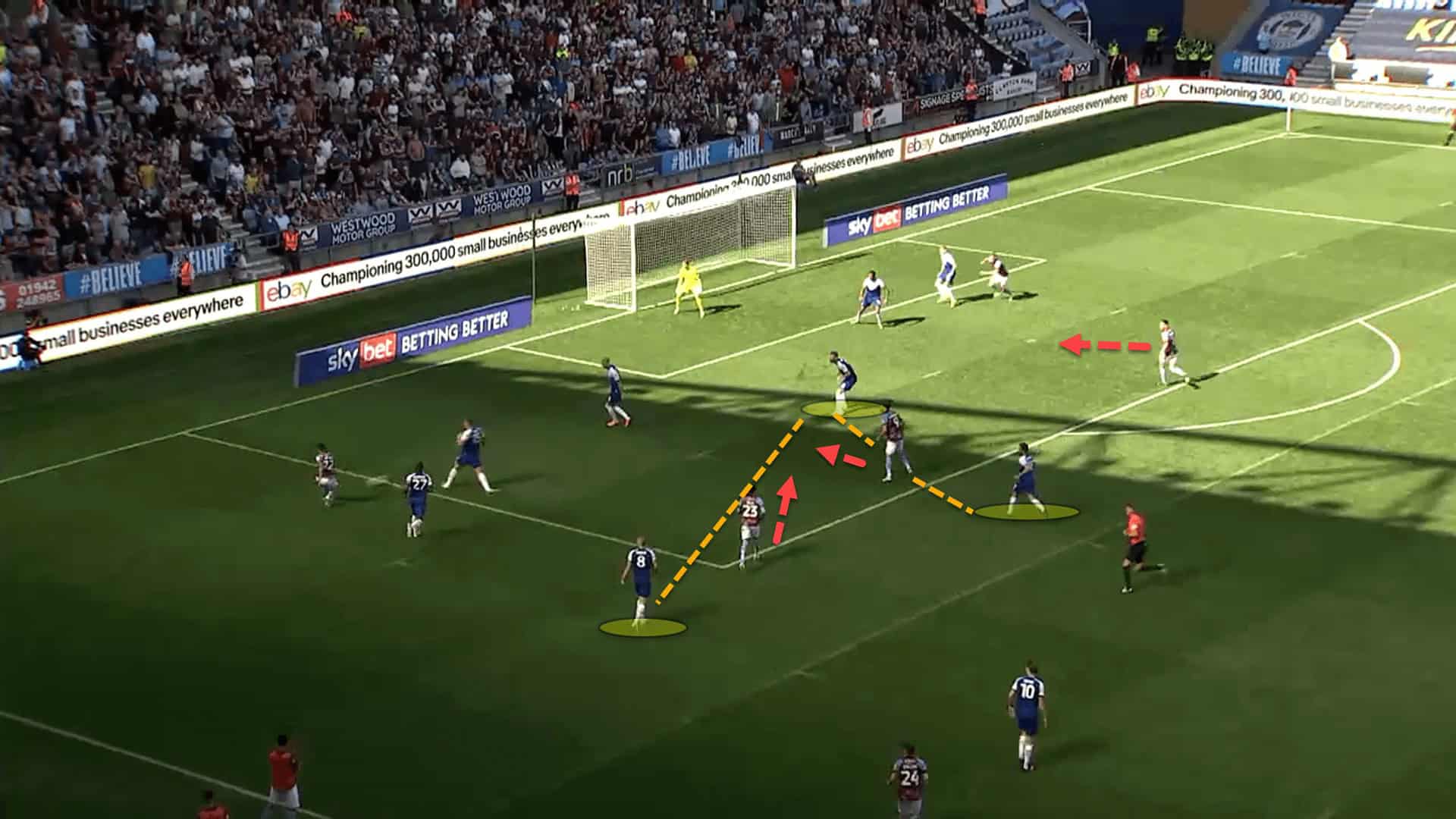

The biggest issue for Wigan was the positioning of the wing-backs. Quite often, when teams defend high in a 3-5-2, the wide central midfielders are tasked with stepping across to press the opposition’s fullbacks, meaning the wing-backs don’t have to commit. This wasn’t the case with Wigan.

Richardson was adamant about pressing man-for-man in the midfield and so the wing-backs had to push high to press the opposition’s fullbacks. This left the three centre-backs having to defend 1v1 duels quite often or to even be overloaded on the last line.

It also meant that when teams progressed past the midfield into the forward line, Wigan’s centre-backs had to be aggressive and step out to close them down from behind.

Wigan may have gotten away with this against opponents of the same quality, but when faced with sides from the top half of the table, this became a little riskier.

These two examples highlight this. McClean was pulled high to press Roberts and the ball eventually reached the feet of Burnley’s Jay Rodriguez. As a result, left centre-back Curtis Tilt had to step out of the back to jump the striker from behind.

As McClean was out of position, Rodriguez simply laid it off to his right-winger Jóhann Berg Guðmundsson. Play developed further and the visitors ended up with a 3v3 situation in the final third, and it could have been a 3v2 had right wing-back Tendayi Darikwa not recovered in time to track Burnley’s left-back Vitinho. Nothing came of this chance, but the danger was there throughout this match.

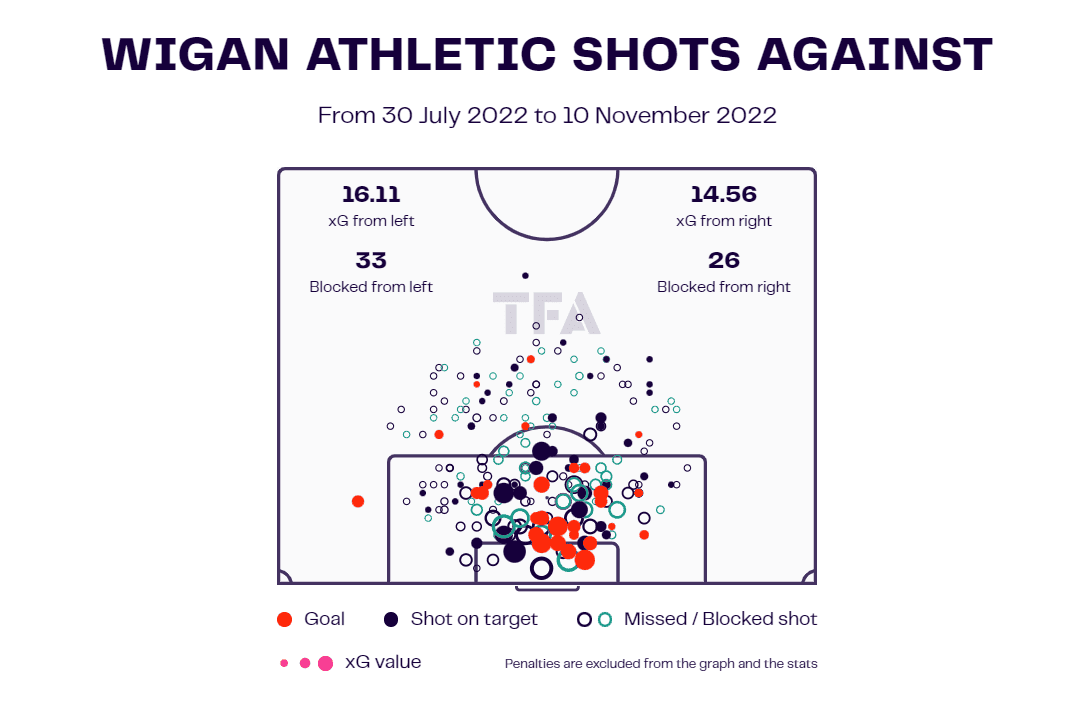

Richardson took charge of 21 games this season in all competitions. The Latics conceded an xG of 30.67 in total which is about 1.46 per game. Furthermore, they conceded 31 goals overall before his dismissal, or 1.48 per game and so Wigan didn’t underperform or overperform their expected goals against.

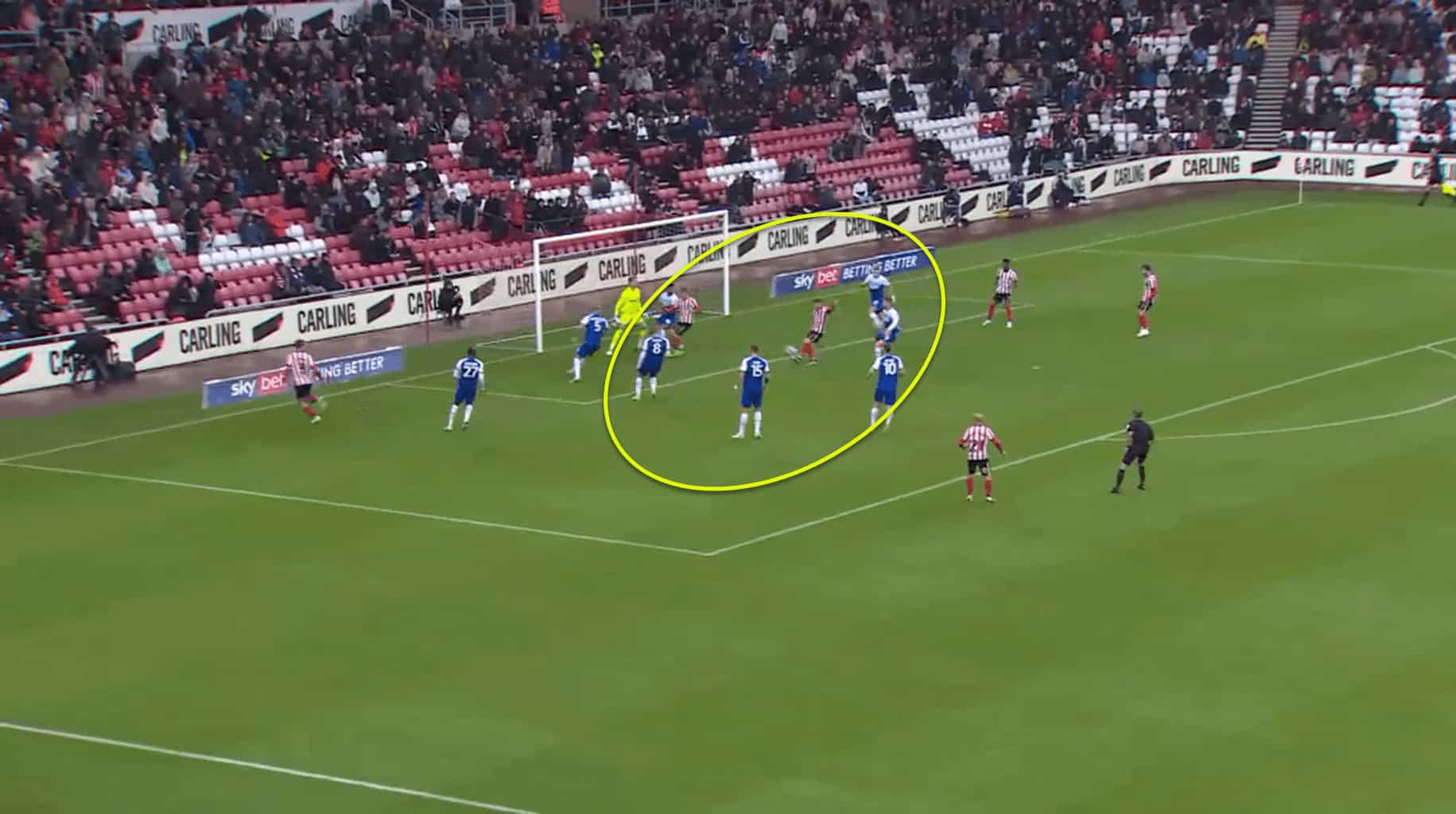

There was a real problem when Wigan were tasked with defending crosses. This regularly stemmed from ball-watching but the lack of midfield coverage inside the penalty area was stark at times.

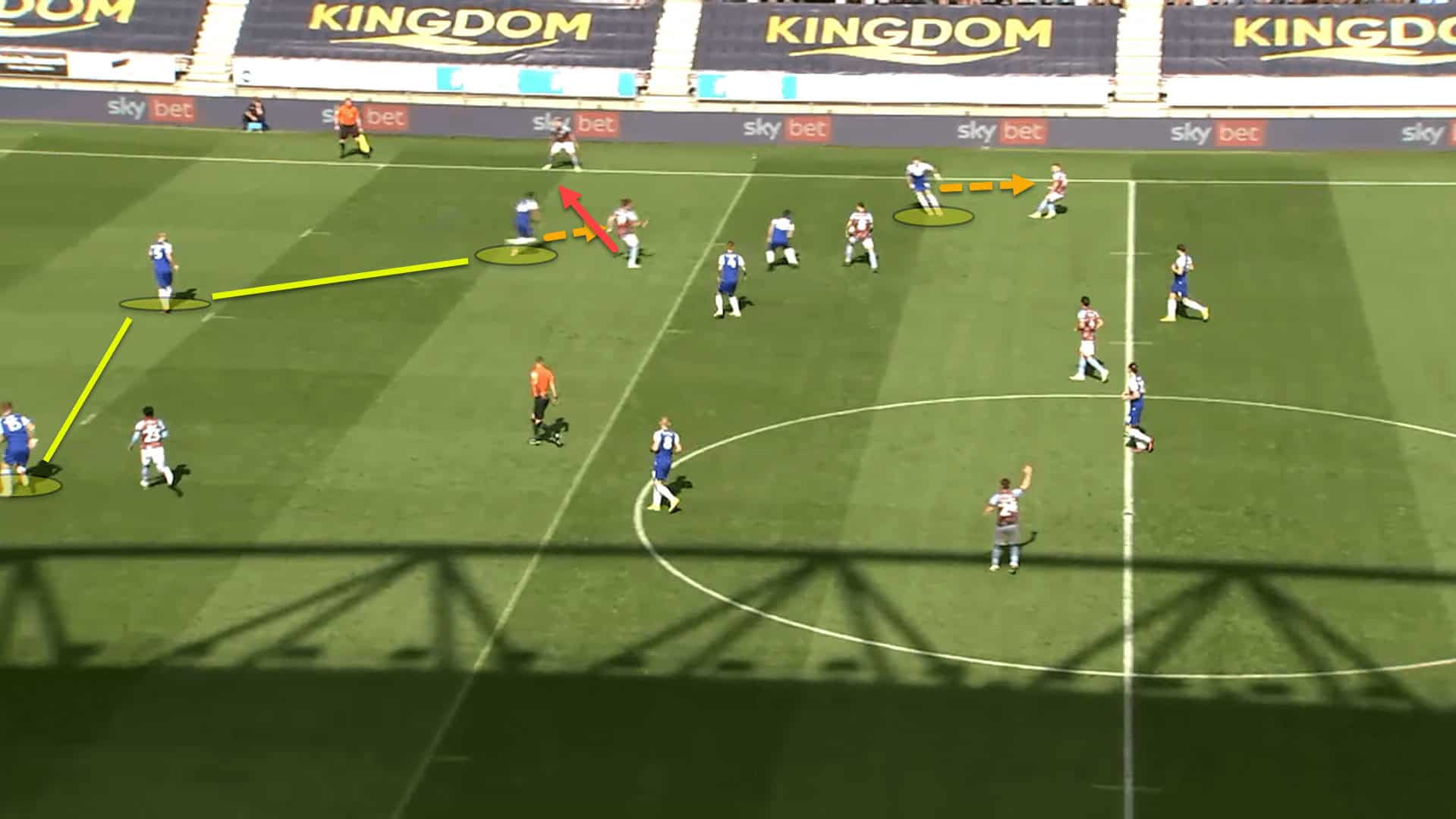

Wigan defended in a 5-3-2 for the most part as the wing-backs would drop back alongside the three centre-backs. Opposition teams regularly tried to get to the byline to cross as they knew the backline would drop even deeper towards the goal. However, they also knew that the midfield wouldn’t do the same.

Here are two examples from this very situation. In the first, Tom Naylor was the only midfielder protecting the space in front of the defence in the case of a cut-back despite there being three Burnley players ready to receive to feet.

Meanwhile, in the second instance, there were plenty of bodies inside the box to defend the cut-back, yet Elliot Embleton still latched onto the ball to place it past Ben Amos in goal.

Conceding goals in this manner became a common theme this season for Richardson’s Wigan. What also became a theme for the newly-promoted side was their lack of potency going forward.

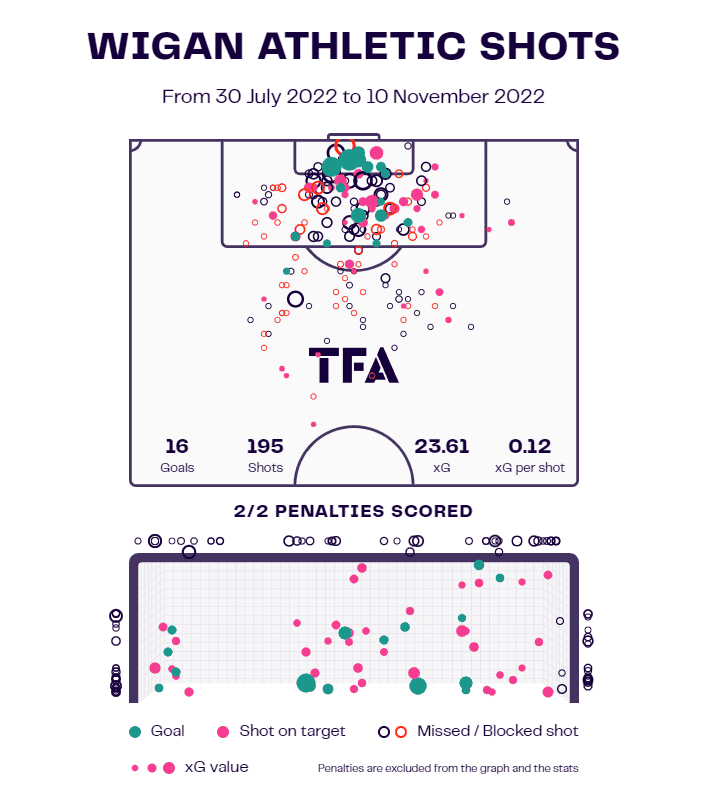

16 non-penalty goals from a non-penalty xG of 23.61 in all competitions is an underperformance in the final third of 7.61 goals. In the 21 games before Richardson was sacked, Wigan averaged 0.76 goals per game and registered an xG per match of 1.12, an underperformance of 0.36 per match. This doesn’t seem too horrendous because you can’t score a third of a goal in a match, but over time, this would add up significantly. And it did.

Conceding 1.48 goals per game and scoring just 0.76 in 21 matches in all competitions. While Richardson had been instrumental to the team’s survival in League One and promotion to the Championship, this record couldn’t continue. It was far from a surprise when the board pulled the trigger on his time in charge.

Kolo Touré

Richardson’s tenure ended with a 2-0 away defeat to Mark Robins’ Coventry City. His assistant coach, Rob Kelly, was placed in charge for a home game against Blackpool which was an important tie in the early relegation race. Wigan came out on top with a 2-1 victory, having dominated the ball with 72% possession.

Nevertheless, Kelly was asked to settle back into the assistant manager’s chair upon the arrival of Kolo Touré, who was named as the new head coach just as the FIFA World Cup had begun in Qatar. It seems like a lifetime ago now.

Touré had an illustrious playing career, having worked under top managers such as Jürgen Klopp, Arsène Wenger, and Roberto Mancini. He was also a part of Brendan Rodgers’ coaching staff at both Celtic and Leicester City, but Wigan was his first head coaching role.

The biggest positive that the former AFCON champion can take from his time at the DW Stadium is that it was an important learning curve. Unfortunately, Touré’s tenure was disastrous. Nine games, six losses, and not a single win. So, what went wrong?

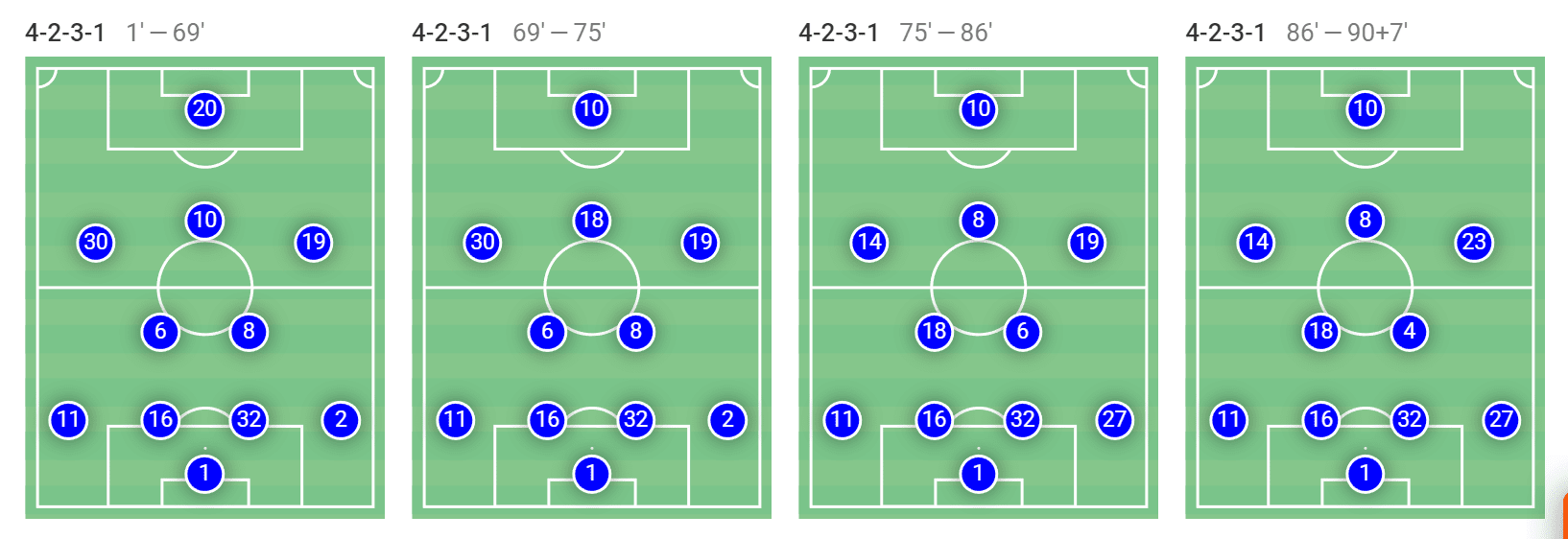

Toure’s first game in the dugout came away from home against Millwall. The team had been used to playing in variations of a 3-5-2 over the past few months but Touré immediately sought to change the formation, opting to go with a 4-2-3-1 from the off. A 1-1 draw on his managerial debut against a playoff contender was a very promising result. But any promise dissolved over the coming few matches following four straight defeats in the league.

One of the most frustrating factors about the new boss was his stubbornness or unwillingness to change the structure. In his final four games, Touré finally reverted to a back three, but the damage had already been done.

In a 4-1 defeat to a superior Middlesbrough side under Michael Carrick, Wigan were being overrun all over the park as the midfield was constantly overloaded, making them incredibly malleable. The game ended 4-1 to Boro and despite the clear structural problems, Touré stuck with his guns and kept the 4-2-3-1 intact throughout the match.

Carrick’s side always build-up with a double-pivot and a three-man first line, with one of the full-backs tucking in while the other advances forward. Furthermore, one of the wingers moves into the central channels while a centre-forward drops a little shorter, creating a box in the middle of the park.

The 4-2-3-1 Touré deployed wasn’t necessarily an issue. The problems arose by how he asked his players to defend out of possession.

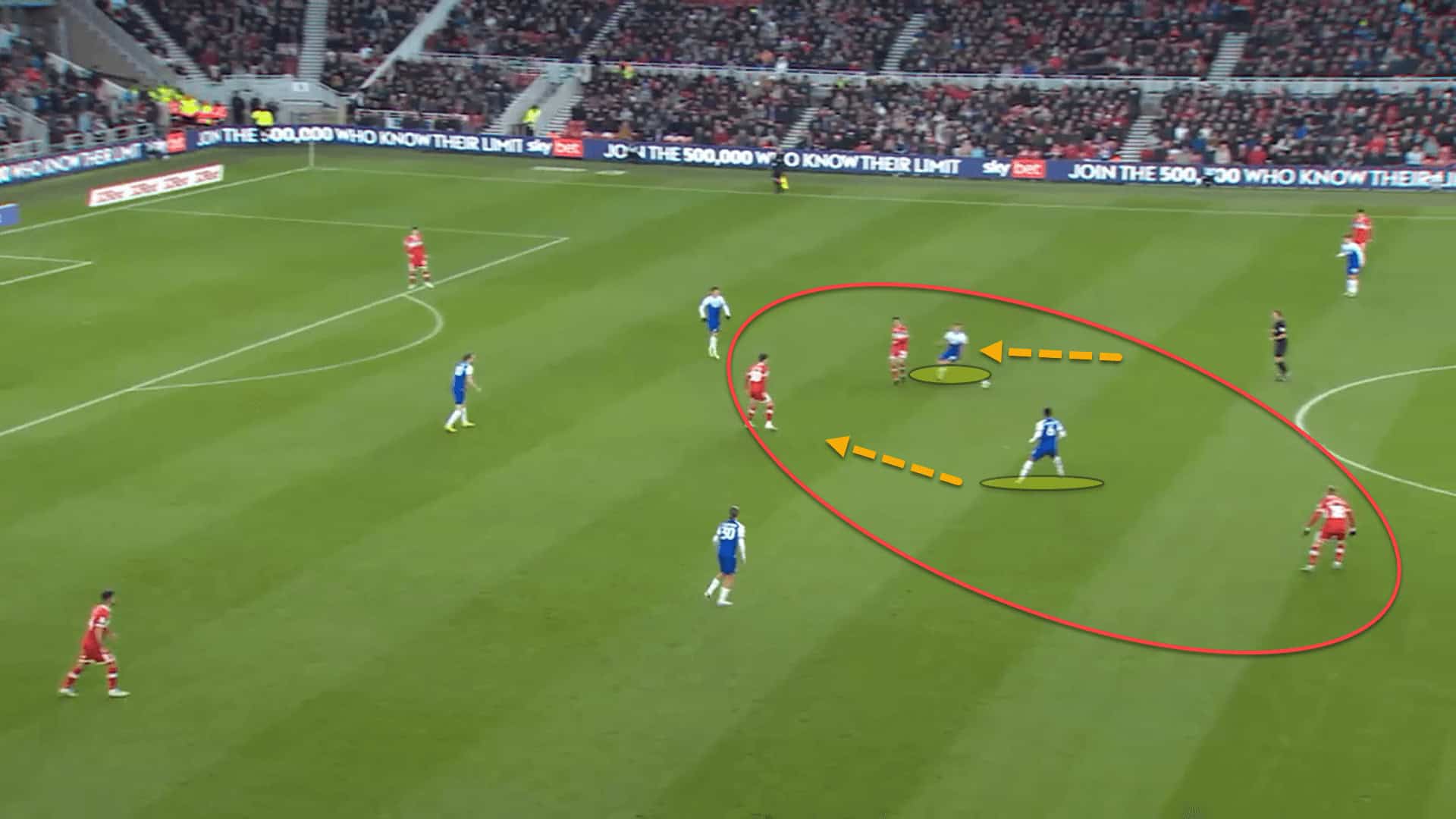

The inexperienced head coach instructed his own double-pivot to man-mark their opposite numbers, stepping really high to do so. This caused space to open up between the lines because the midfield and backline were distanced from one another. As a result, Boro were able to create a numerical overload in the midfield with the tucked-in winger, causing a 3v2 to occur and sometimes a 4v2 if the striker dropped short.

The Teesside club were constantly able to find this free man behind Wigan’s double-pivot and so once the midfield was easily bypassed, the backline was left scrambling back towards their own goal.

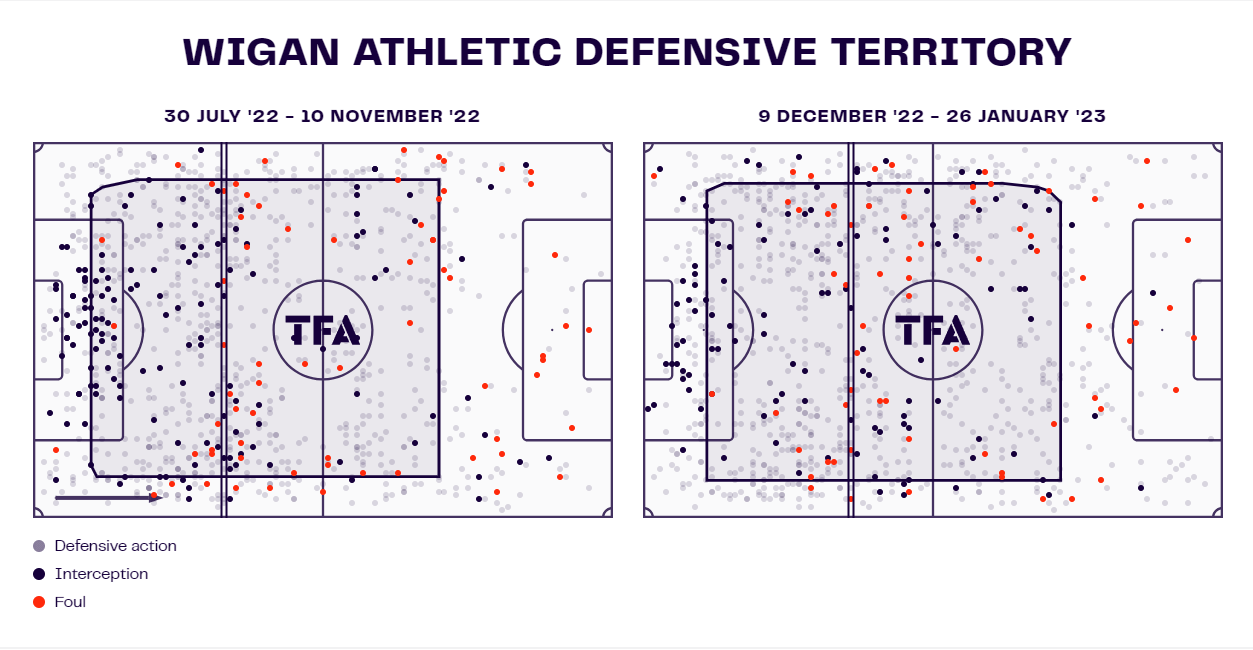

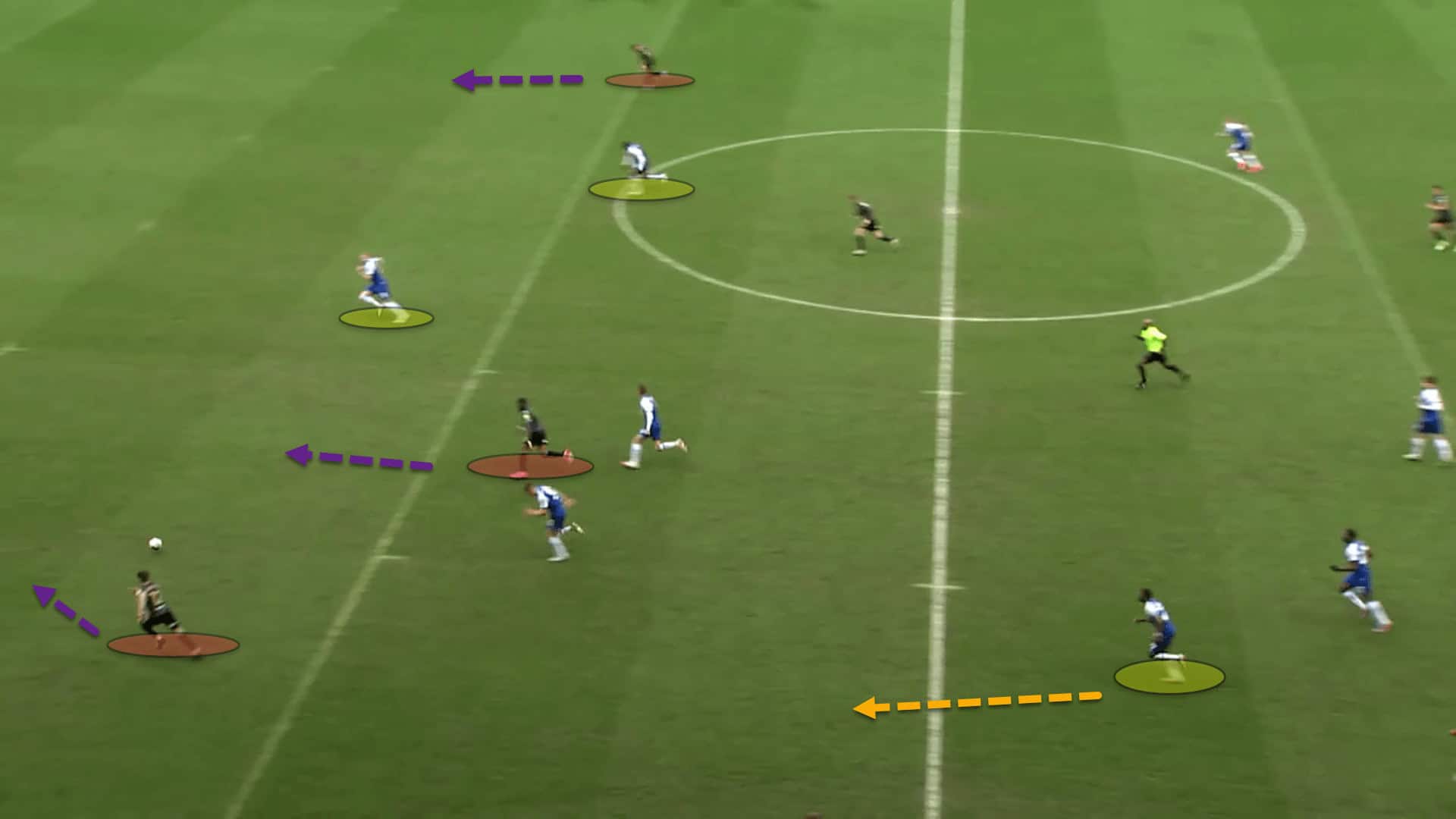

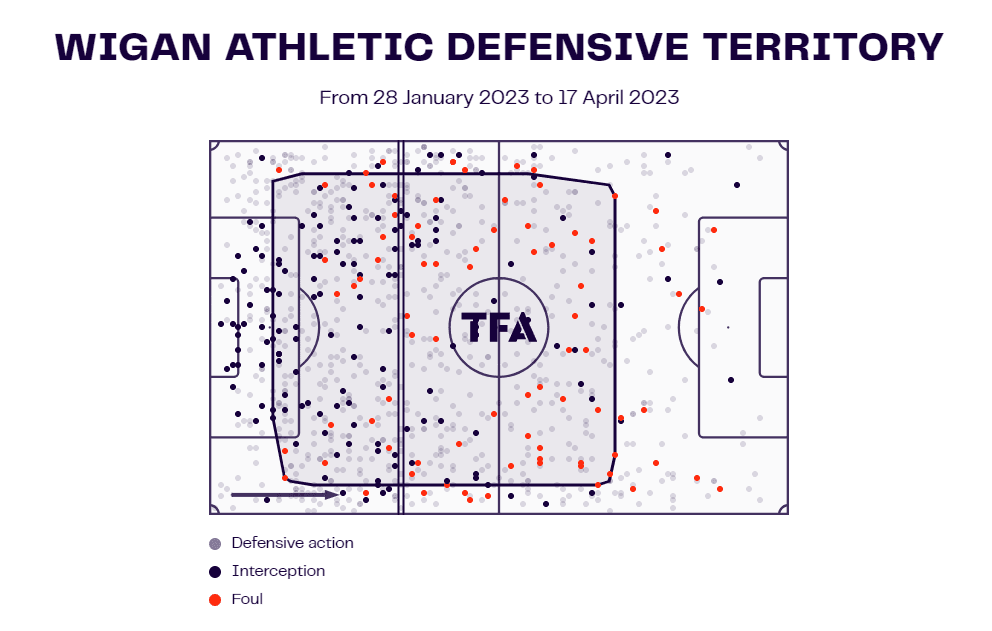

Overall, Wigan began defending higher up the pitch too on average.

Under Richardson, Wigan pressed high but quickly ceded into a defensive low block once the opposition broke through the press. Touré preferred his men to defend a little higher in a mid-block, as can be seen from the previous data viz.

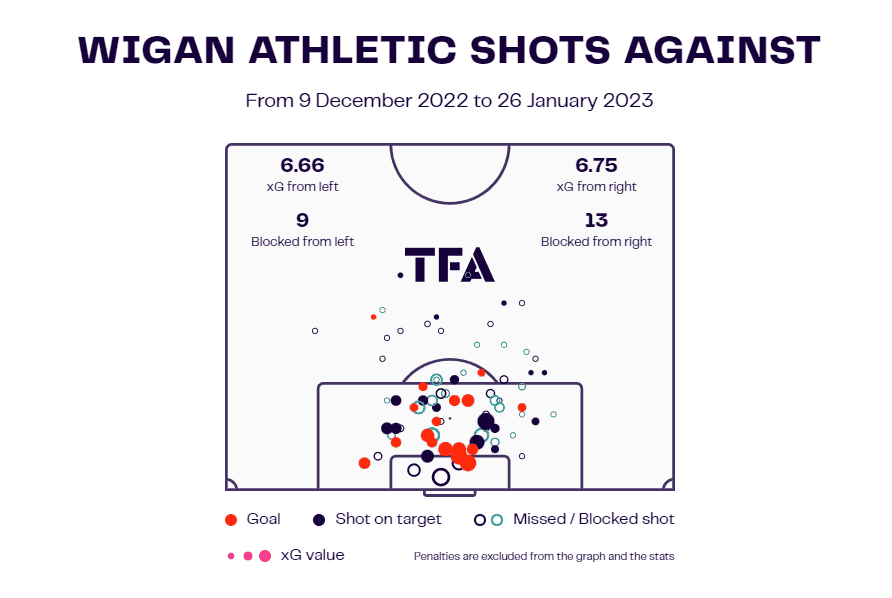

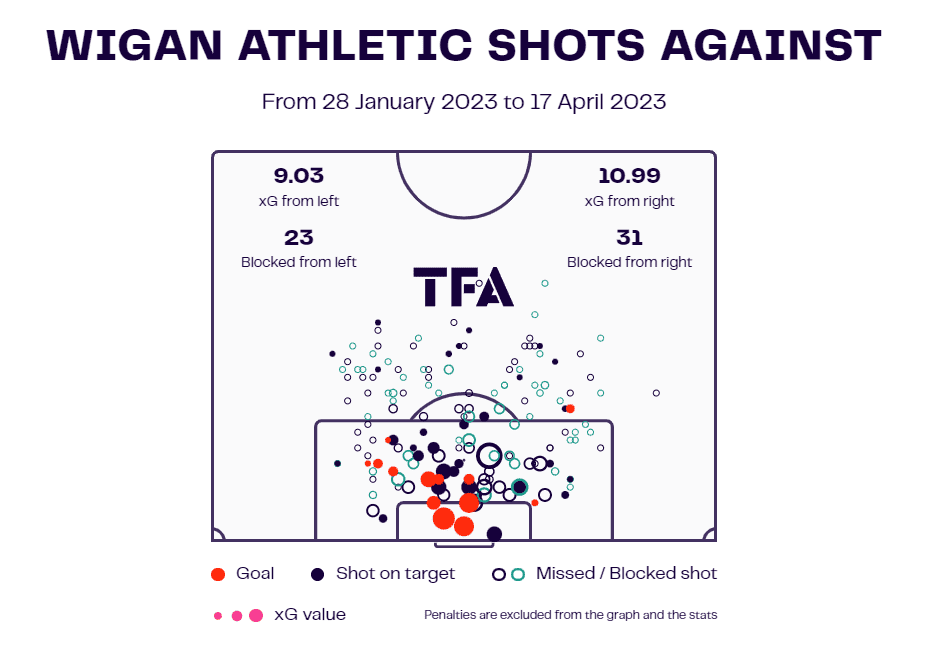

Defensively, it was quite a shambles during Touré’s spell in the dugout. Over the course of nine matches in all competitions, Wigan Athletic conceded an xG of 13.41 which averages out at 1.49 xGA per game. Opposition teams were able to create far too many chances around the six-yard box which can be classified as high-percentage opportunities.

For a team to survive in a league, punching above their own weight, defensive security is perhaps the most important attribute needed. Wigan didn’t have this under Touré — or under any manager this season, for that matter.

The Latics conceded 19 goals in these nine games, which is 2.1 goals per match, way higher than the 1.48 that they were allowing under Richardson.

But did things change from a goalscoring perspective? Kind of… but not really.

Wigan scored 0.76 goals per match under Richardson. This increased slightly to 0.78 goals per game during Touré’s reign, but the sample size was much smaller considering his predecessor was in charge for 21 games of the campaign.

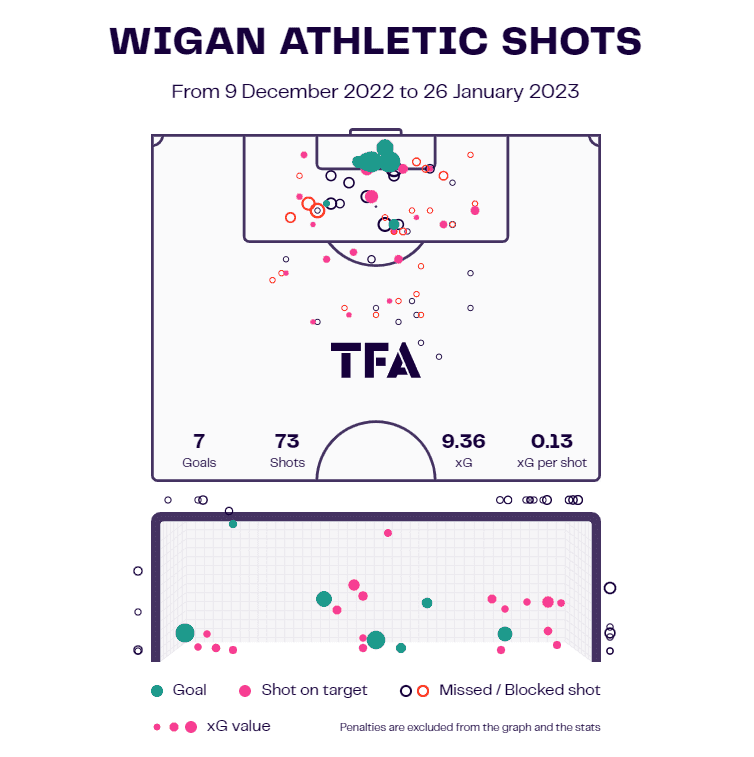

Furthermore, Wigan registered a total xG of 9.36 during Touré’s time at the club, an average of 1.04 xG per game which was lower than the 1.12 xG averaged per game under Richardson. This was an average underperformance of 0.34 for each match.

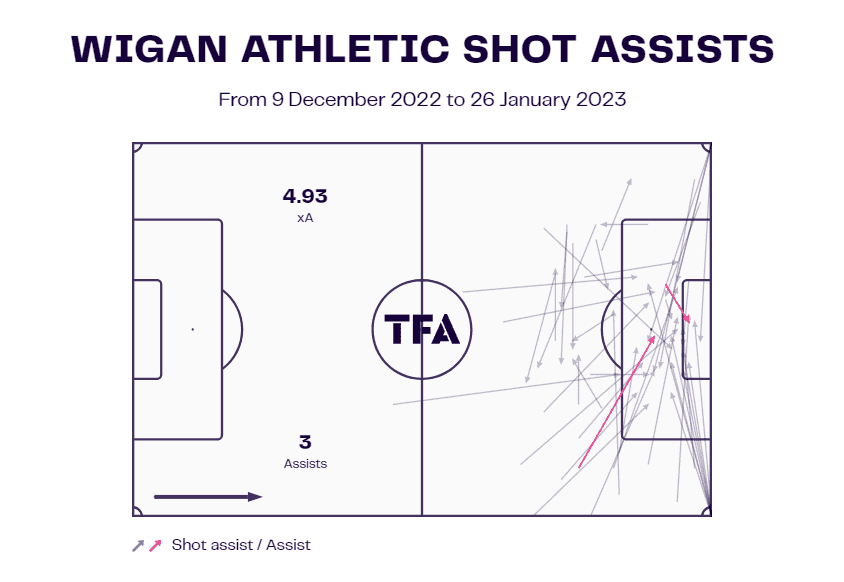

The most worrying aspect of Wigan’s lack of quality in the final third was how the chances were created.

As is detailed in the data viz, which analyses each pass that led to a shot, quite a lot of created opportunities were from corners or from early crosses, which are low percentage chances and so it’s not a surprise that Wigan weren’t putting the ball into the net enough. Quite a lot of the goals that they did score were in or around the six-yard box, but unfortunately, these were few and far between.

Touré was dismissed late into January after failing to win a single game in his nine matches in charge as Wigan sat rock bottom of the Championship, staring down the barrel of relegation. However, the Latics were just four points adrift of safety and were willing to have one more throw of the dice. This one had to work out.

Shaun Maloney

Shaun Maloney indoctrinated himself into Wigan history by providing the cross for Ben Watson’s powerful near-post looping header to beat Manchester City in the FA Cup final ten years ago.

It made sense to appoint him as the new man in the dugout. A familiar face around the club and a man that can get the fans back onside. The former Scotland international was still an inexperienced coach but had more experience leading a team than his predecessor, having overseen cinch Premiership side Hibernian for the guts of five months last season.

Still, keeping the club he loves in the second tier would be his most challenging task yet.

The 40-year-old got off to a flying start, going on a four-game unbeaten run which included three draws and one win against relegation rivals Huddersfield Town.

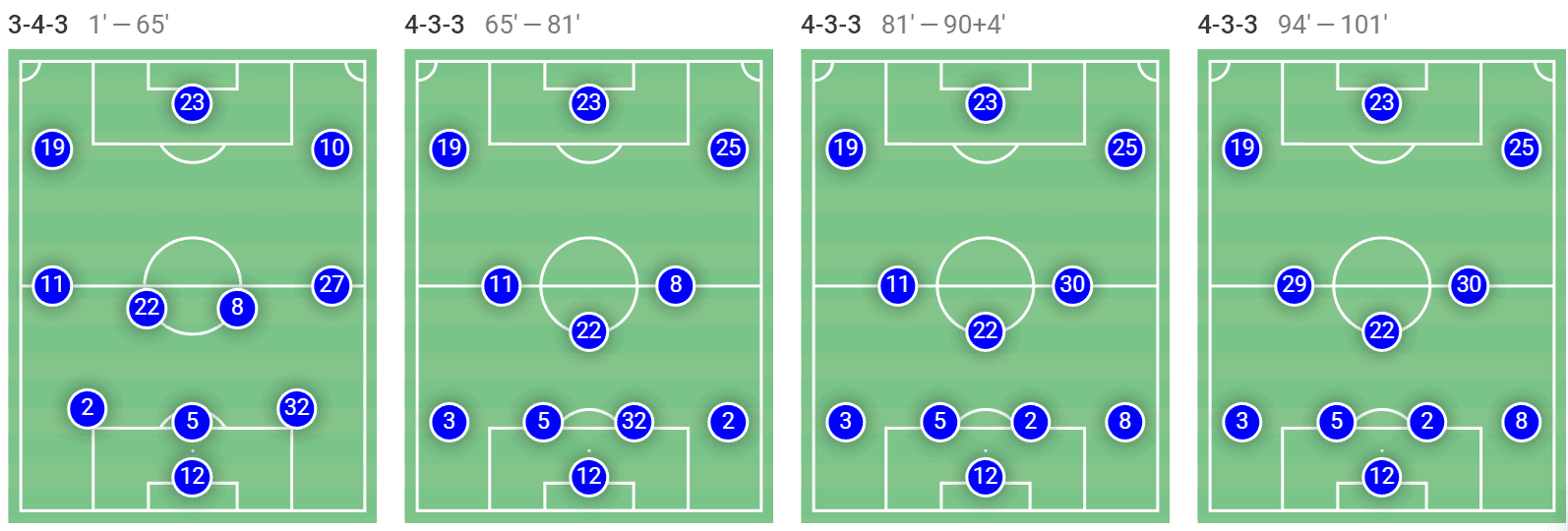

Similarly to Touré, Maloney switched to a back four from the get-go, deploying a 4-4-2 in his first few games, particularly against opposition where he believed they could get a result. Nevertheless, in his fourth game with Wigan, which ended in a goalless draw at home against Norwich City, the new boss changed to a 3-4-1-2 and never looked back.

But he isn’t as tactically rigid as the man he replaced at the DW Stadium. When things aren’t going right, Maloney has no qualms about changing things up on the pitch from a tactical perspective.

Wigan had the lead at half-time through a Greg Cunningham own goal while Preston failed to register a single shot on target. But the Latics were struggling for possession of the ball. By the 57th minute, it was 2-1 to the Lilywhites. Maloney recognised the need for a tactical change and so switched to a 4-3-3. While the result stayed the same, Wigan’s possession numbers increased from 42% to 55%.

Out of Wigan’s three managers this season, Maloney and Richardson were the most alike in terms of their styles. Both pressed in a very similar manner up the pitch too, which wasn’t necessarily a good thing.

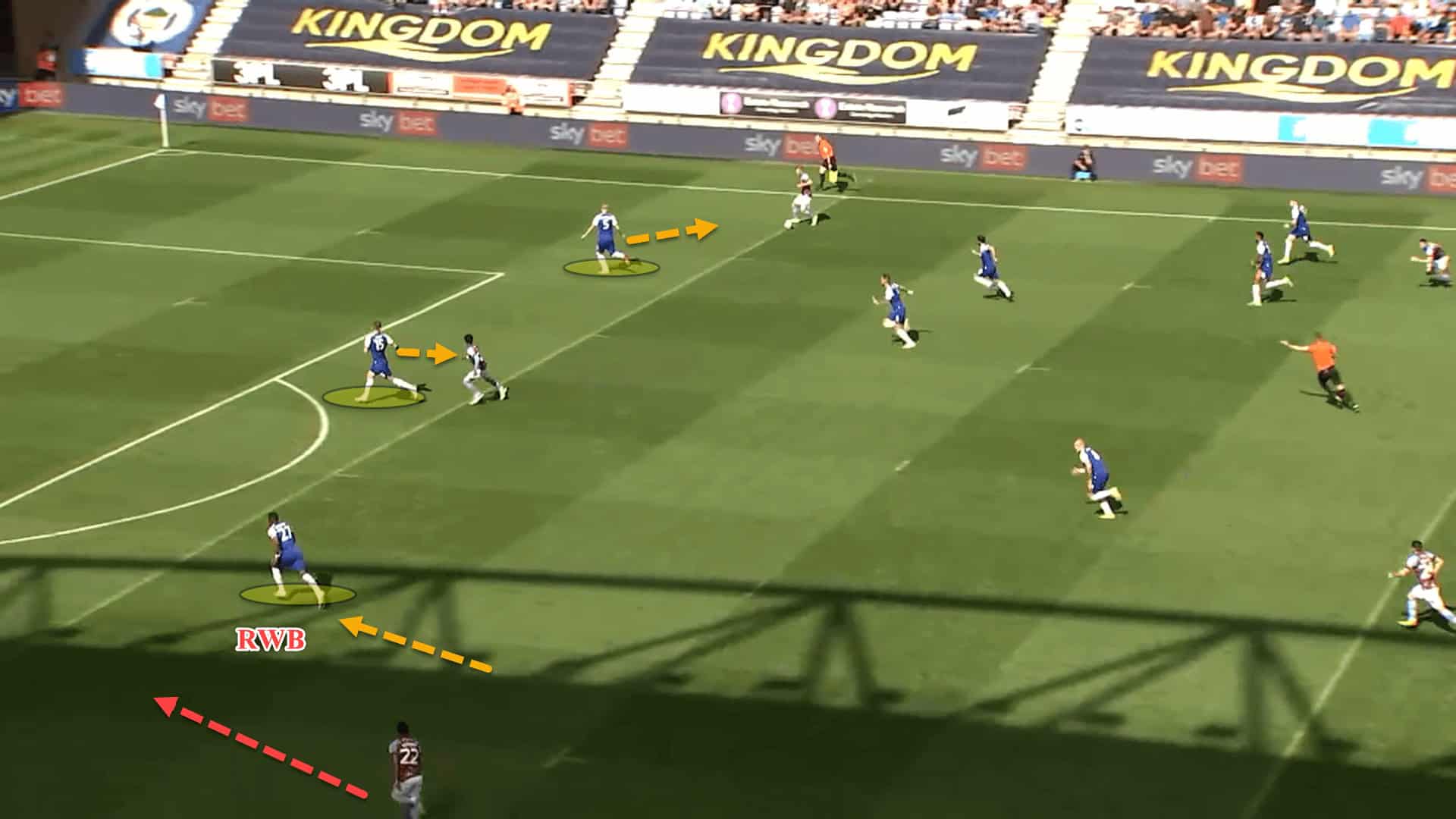

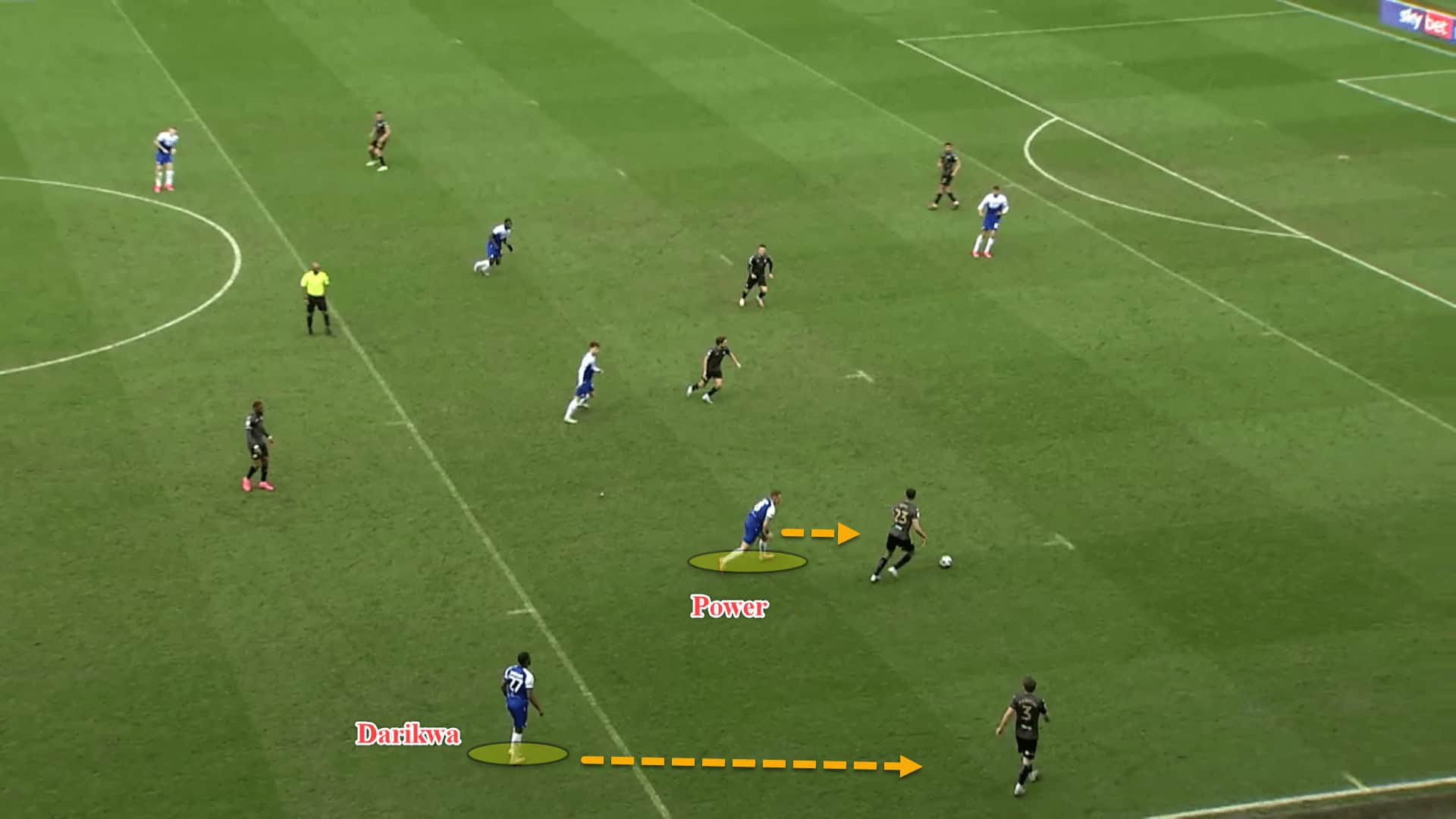

Here, for instance, Wigan were pressing in a man-to-man fashion against Swansea City as the Welsh team attempted to build up from deep. In the screenshot, we can see right-sided central midfielder Max Power telling right wing-back Darikwa to step forward to get up to Swansea’s left wing-back Ryan Manning.

Darikwa was hesitant to do so because Swansea would have had an overload against Wigan’s backline but reluctantly obliged in the end.

Play developed further and the Swans managed to take advantage of this space down the flanks by playing through the press, indeed having an overload at the back. A goal came from this situation.

Going man-for-man can make sense in certain circumstances. It is an old-school throwback to a simpler time in football where individual battles trumped the collective effort. The downside to this approach is that if one team have more quality all over the park, they will likely win most of these battles which can cause problems.

Keeping in line with similarities to Richardson, when Wigan are pinned back, he prefers his players to drop into a low block instead of a mid-block which was seen during Toure’s reign.

Maloney did manage to massively reduce the team’s defensive record from the abysmal numbers being seen under Toure to around the same as when Richardson was in charge.

As of writing this, and bear in mind that the season hasn’t ended as of writing, Wigan have registered an xG of 20.02 in total which comes to an xG of 1.43 per game. Under Richardson, the xG per match stood at 1.46, so there is not much difference there.

Furthermore, Wigan have conceded 14 goals in 14 games so far — a goal a game. This is the lowest the Latics have seen this number in the current campaign under the three managers.

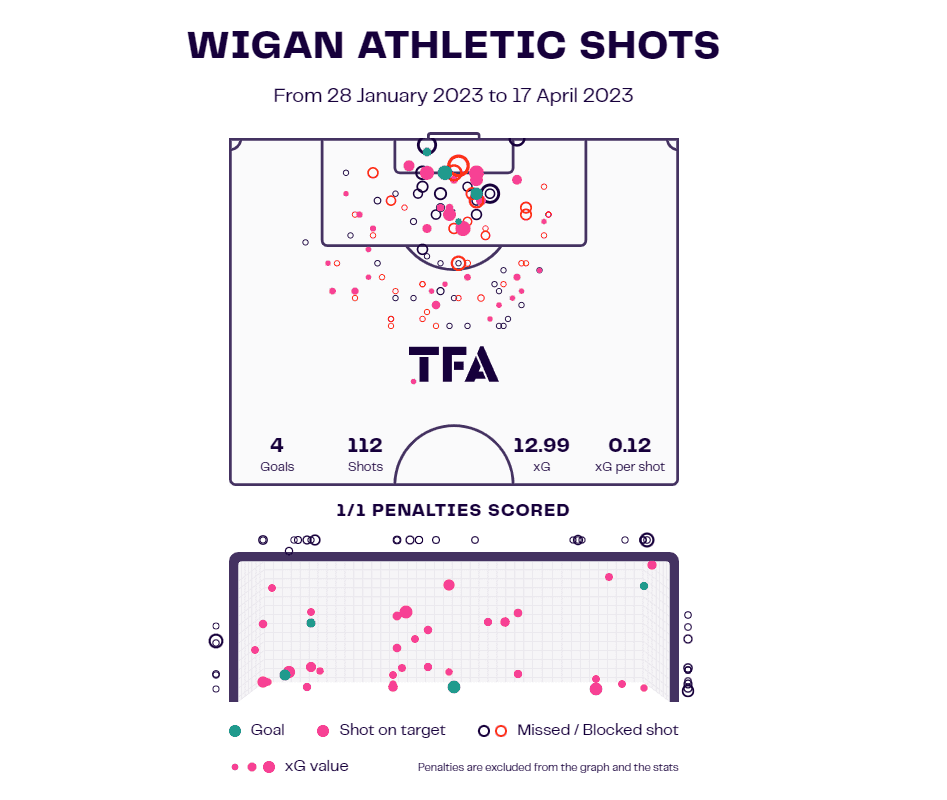

However, what hasn’t improved and has gotten worse is their goalscoring form. In Maloney’s 14 matches, Wigan have scored seven times, including one penalty and two own goals. Just four came from a Wigan player putting it home from non-penalty situations.

Analysing these statistics even further, the Latics are underperforming their xG of 12.99 by almost nine — not pleasant reading for supporters. There have been far too many strikes from outside the box which are low percentage chances and so would inflate the xG numbers but the opportunities that do fall to Wigan players in dangerous positions are not converted.

Seven goals from 14 games equal just 0.5 per match, their lowest average of the season so far under any head coach; 0.93 xG per game is also the lowest of the three. Maloney managed to improve things defensively, although still not enough, but the team’s struggles in front of goal have meant they’re finding it increasingly difficult to buy a win.

Conclusion

Full disclosure, if you haven’t realised already, this team scout report has been written with four games to go in the 2022/23 season. Wigan are eight points adrift of safety. By the article’s release, their fate may have already been sealed.

Cutting the players some massive slack here but being asked to give your all without receiving payment for your efforts would take its toll on anyone. However, this piece wasn’t intended to go in-depth on these problems which have been well-documented in the press.

We are a tactical analysis magazine after all, so it was solely intended to analyse the on-pitch frailties which have led to the side falling slowly back down to the depths of England’s third tier.

Ultimately, someone must finish last in any league table. Unfortunately, the Latics were the casualties this time around.

Comments