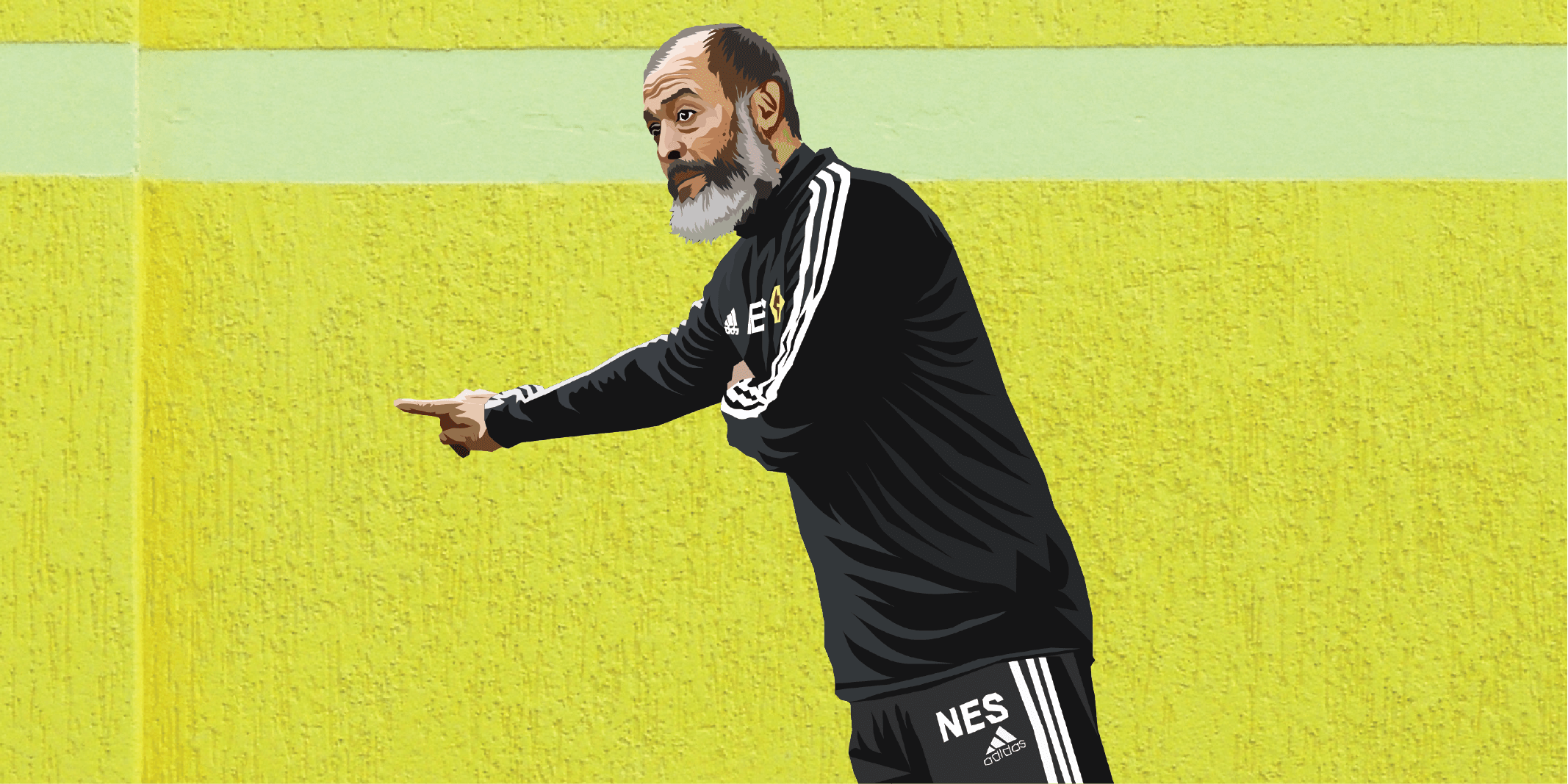

Ever since Nuno Espirito Santo’s arrival at Wolves, their subsequent success has been based on a very recognisable style and brand of football. The Portuguese manager has become known for putting together a well-drilled, disciplined unit capable of scoring goals, and he did so on the back of an almost-constant formation. Wolves have played in a 3-4-3 or a 3-5-2, for the entirety of Nuno’s tenure, right from their Championship win to the last couple of seasons in the Premier League. This season, however, has seen a change, with the manager occasionally moving to a back four. Wolves have used a 4-2-3-1, and occasionally a 4-3-3, this season, in a bid to improve their creativity and possession while also being able to retain the solidity that has been a hallmark under Nuno. However, the jury is still out as to whether this shift has been successful, and the team have been changing their shape frequently, playing with a back three in one game, going back to a back four for the next couple, and again reverting to a back three for another match. Thus, this tactical analysis piece will attempt to determine if Nuno’s switch to a back four this season has been successful, or whether they are better served by sticking to what they know so well.

The shape and personnel

Wolves first lined up in a back four for the game against Southampton, where Nuno was without Conor Coady. The former Liverpool player, and Wolves captain, has been a big part of their rise over the last few years, and has been exceptional at the heart of a three-man defence, which has recently elevated him to being capped for England as well. Coady has been ever-present under Nuno, and this game marked the first time in three years that he would miss even a minute of league action. However, nobody was expecting Nuno to send the team out in a 4-3-3 as a result, with Willy Boly and Max Kilman at centre-back, Nelson Semedo and Rayan Aït-Nouri as the full-backs, and Leander Dendoncker, João Moutinho and Rúben Neves in midfield. It was also surprising that Kilman and Boly played on the ‘wrong’ sides i.e. the left-footed Kilman played on the right and the right-footed Boly was on the left. Since then, Wolves have started with a back four in seven of their ten games in all competitions, with Coady also being slotted into the back four, despite not having played in that system for Wolves previously. The likes of Kilman, Boly and Romain Saïss have partnered Coady, as well as forming pairs themselves occasionally.

It was always thought that Coady would be the man to miss out if Nuno ever switched to a back four, since he was playing in such a specific role as the sweeper in the three, that there were doubts about his ability to play in a different system. Wolves’ system also relied on organization and partnerships, which meant that Coady was rarely exposed in 1v1s and individual duels, but that would be much more difficult to do in a back four. This was also the reason why he was not called up to the England squad for so long, before Gareth Southgate switched back to a three at the start of 2020, and this opened up a spot for him. It is ironic for Coady that he is once again playing in a different system to that which England employ, albeit it is the other way around, with Wolves in a back four and England employing a back three. He has been able to adapt well to this change so far, but like his teammates, there have been some struggles as well.

Of course, asking a team to play a completely new shape for the first time in nearly three years is bound to bring some teething problems, and it has been no different for Wolves. However, what will worry Nuno is that they have continued to look fragile at the back. Wolves have conceded 13 goals in the seven games they have played with a back four, although that is inflated somewhat by the four strikes that Liverpool put past them.

We will look at their shape and certain issues that have arisen from this approach next.

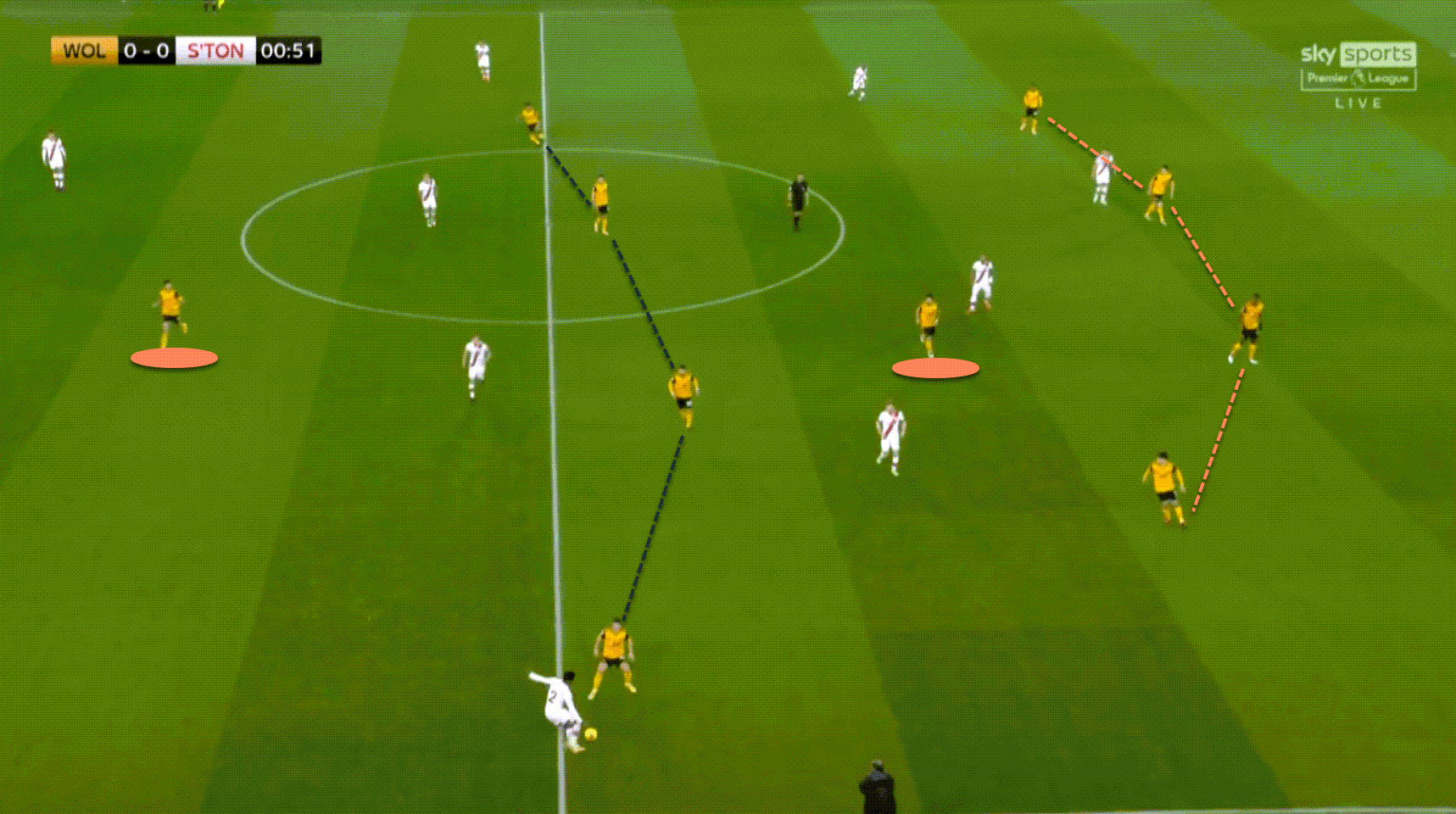

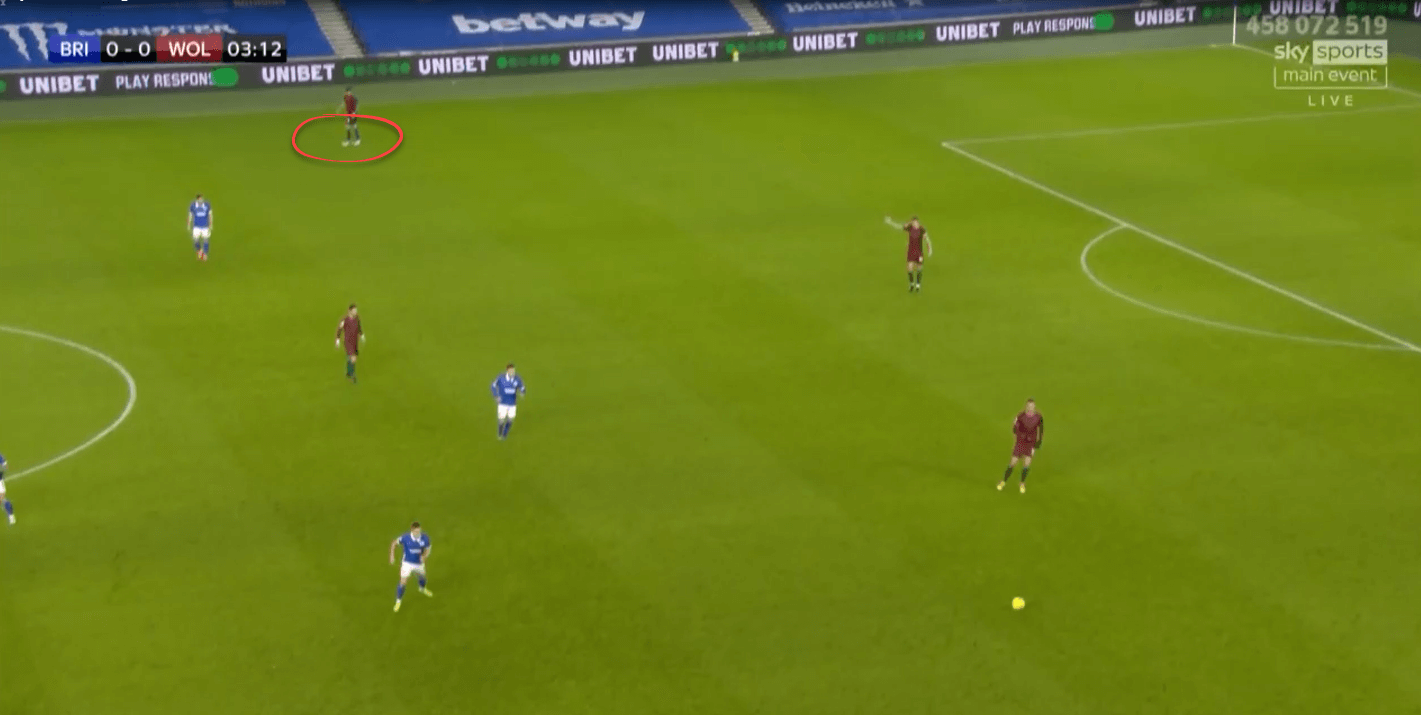

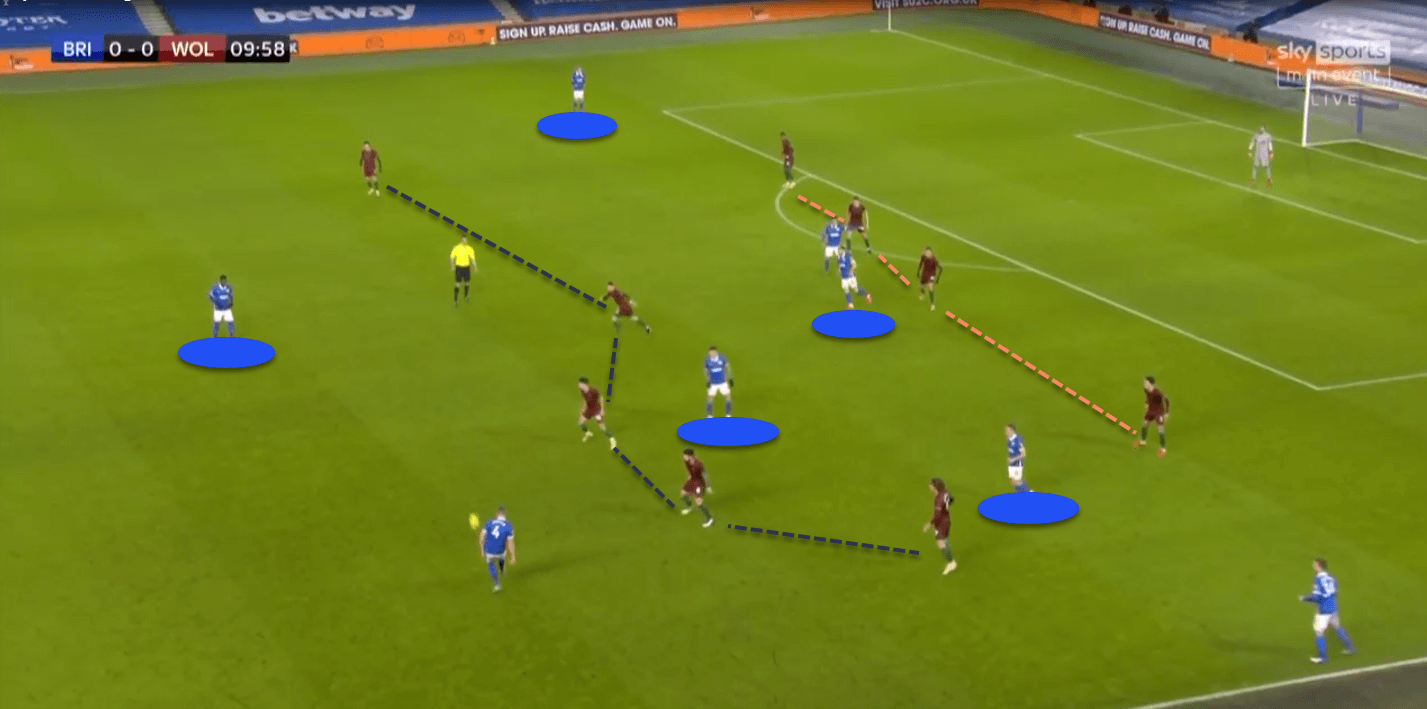

Early on in the game against Southampton, we can see Wolves’ shape clearly –

Wolves are in a 4-1-4-1 without the ball. Moutinho is the anchor in midfield, with Raúl Jiménez leading the line. This basic shape has been tweaked a little, with a 4-2-3-1 also being used, but the principles have remained the same. Playing a back four has meant that the defensive line has stayed narrow, with the wingers expected to track back and protect the full-backs during opposition attacks, while we will also see variations where one of the central midfielders has dropped into the full-back positions, to allow the full-backs themselves to bomb on higher up the pitch.

We will now look at some of the consistent traits and patterns of play that Wolves have employed in this shape, as well as errors, which may be a result of unfamiliarity with the shape or individual mistakes.

In possession

One of the most basic, but important, reasons for Nuno to play a back four was to get another attacker on the pitch, to hopefully increase Wolves’ offensive threat. The team have struggled to score goals this season, as can be seen by the fact that they have only scored 18 goals from 17 games (1.06 goals/game), which is the fifth-lowest in the league at the time of writing, while their creativity has not been too high either. Wolves have had the ninth lowest non-penalty xG this season (21.06), while they have had the second-lowest xG per shot as well (0.116). Given that Wolves are taking nearly the same number of shots per 90 this season as last season (10.60 vs 10.31), this is a clear indication that they are not getting into good goalscoring positions. Thus, it is understandable that Nuno has opted to try and improve the side’s creativity and attacking threat by changing the team’s shape, and we will see how this has helped improve various aspects of their attacking gameplay.

One of the ways in which this shape has helped Wolves is by improving their threat from wider areas. Playing a full-back and a winger naturally means that there are greater opportunities for overlaps, underlaps and other combinations, which can allow the team to break down opposition defences. This also stretches the opposition, which can then create space in central areas for the other attackers. We will see examples of all of this in Wolves’ play this season, which is an encouraging sign.

This is a great example to show the effect of playing with wingers on team shape. As Wolves build-up from deep in their own half, notice how wide their attacking line is. At the same time, Vitinha (marked in red) is playing as a number 10, allowing for combinations with the striker as well. The shaded areas in yellow are approximate markers for where Wolves’ wing-backs would have been if they were playing a back three, and it is immediately evident that they would be much deeper and therefore would not carry the same threat in behind the opposition’s defensive line.

Another consistent facet of Wolves’ play in this shape has been the insistence on holding width, even though the identity of the players’ staying wide has changed.

Note how Aït-Nouri can come infield on the ball, because Pedro Neto is staying wide.

A similar situation in a different game – Neto is once again wide on the left, which allows Fernando Marcal, playing at left-back, to move into the central spaces.

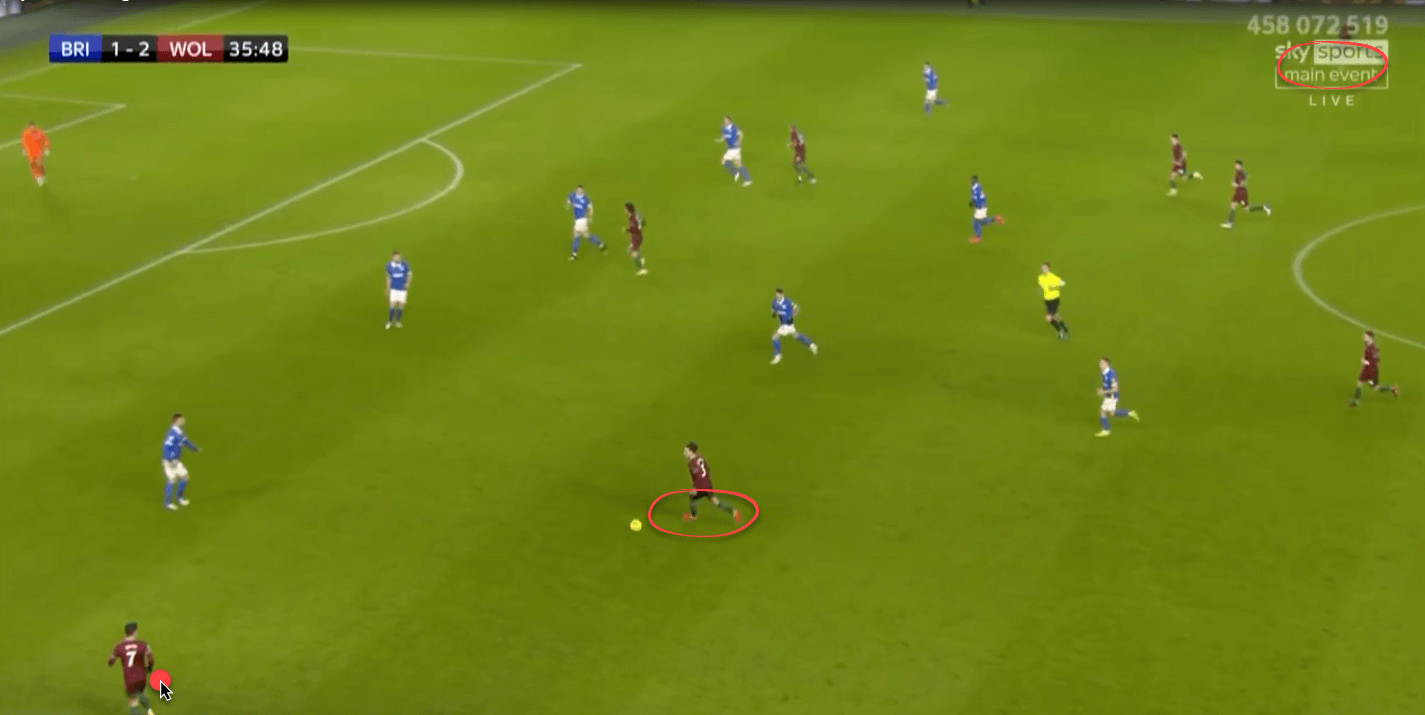

This has been seen on the opposite flank as well – Adama Traore stays wide which allows Nelson Semedo to make a run infield. Note how Neves (highlighted in red) is moving across to the right to cover for Semedo. This has been a feature of Wolves’ play, with this positional rotation allowing the full-back to take up positions high and wide on the pitch, and subsequently bringing the winger infield, as we can see in the next image.

Neves is in the right-back spot here, with Semedo having advanced high up the pitch

Here, Traore comes deep and into a central position, opening up the flank for Semedo to bomb into.

These positional rotations out wide are a great way to create space in dangerous areas, and it is a very encouraging sign that the Wolves’ players have already been able to make these movements, despite having not played in a back four under Nuno before this season.

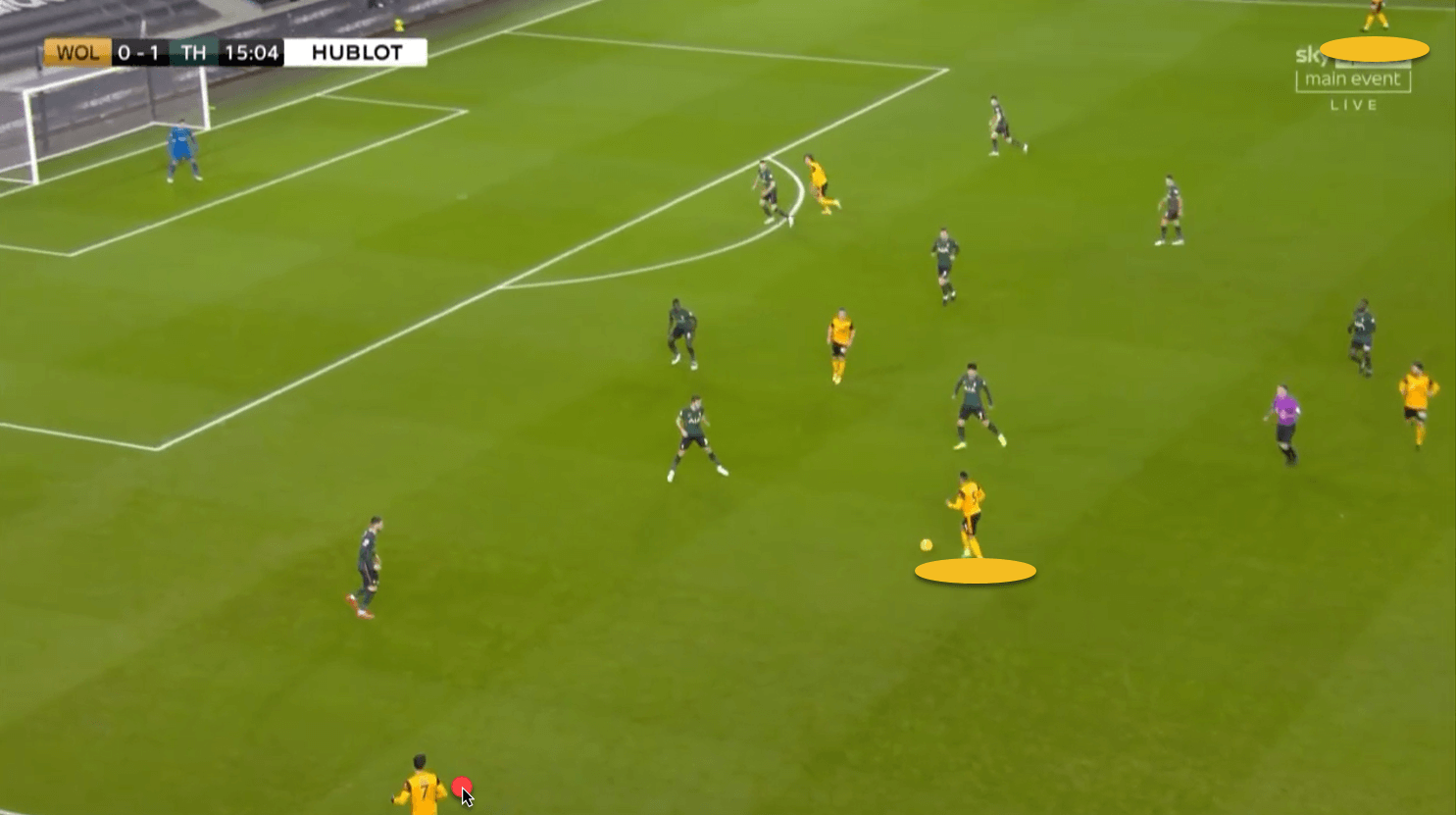

The effect of having width from both full-backs and wingers can be seen in the next image –

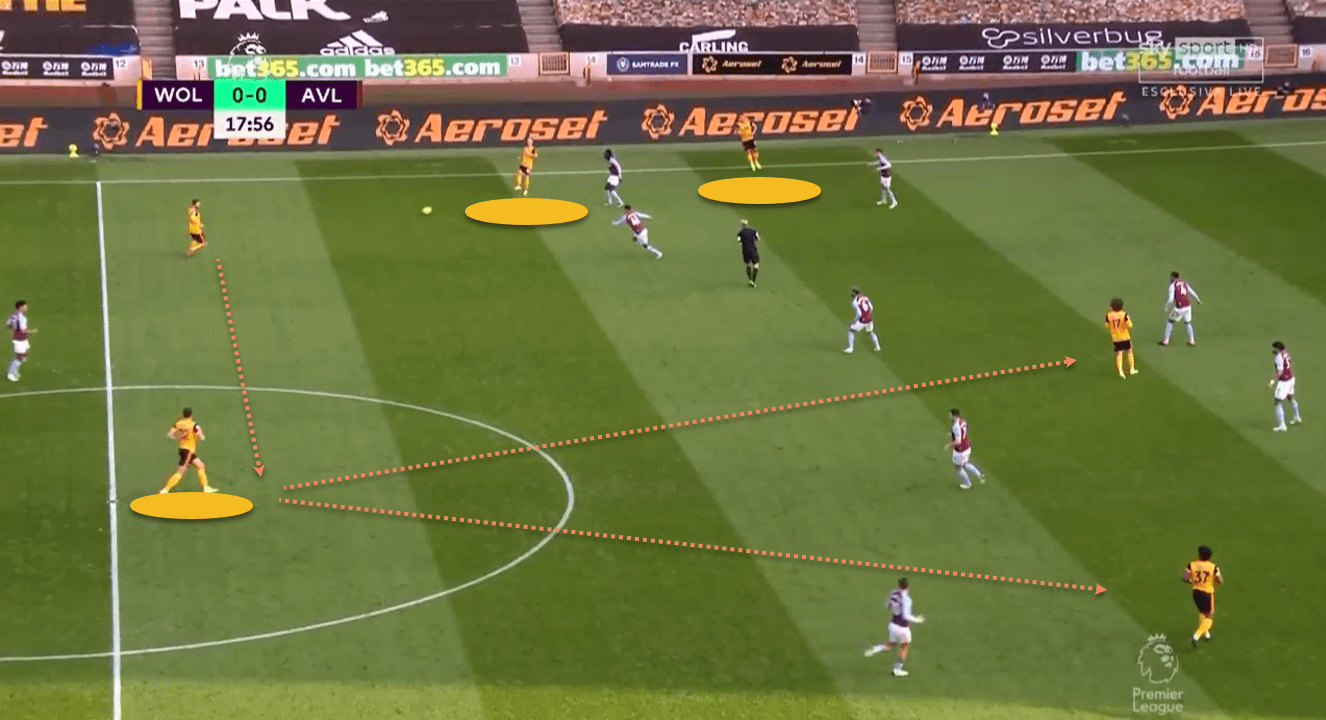

Here, Wolves have a winger and a full-back advanced down their left, which has caused Villa to shift over to that side. This has opened up a lot of space for Leander Dendoncker in the centre circle, who can then play passes to Fabio Silva or Traore in dangerous positions, if he receives the ball quickly from Moutinho.

As the move develops, we can see exactly how this shape allows the Wolves attackers to get into threatening positions.

We can see how Pedro Neto has been able to pick up a position between the Villa lines, and is actually gesturing for the ball to be played into his feet. Semedo opts to play the ball out wide to Traore instead, but it is the Spanish winger’s wide positioning in the first place which allows Neto to find that space between the lines – something that would not have developed if Wolves were playing with a back three and wing-backs.

The advantage of playing with a back four is that it allows players to get into the central half-spaces, by coming infield from the wider areas, due to the full-backs being able to occupy the wide spaces. Of course, this requires discipline from the central midfielders, who will need to either stay deep or drop into the wide areas, like we have seen with Neves, to maintain the team’s defensive structure. Therefore, it is encouraging that Wolves have been able to create such opportunities, even though their goalscoring itself has not improved by too much since they started playing this system. Jimenez’s injury has a lot to do with this, since it has robbed the team of their most effective and clinical striker, and it will be interesting to see if there is a change in their goalscoring output should they sign a new striker in the January window.

Out of possession

The team has needed to adapt a lot more when out of possession, especially the centre-backs. It is quite a change to go from playing as a centre-back in a back three to one in a flat back four, which is why there were concerns around whether Coady, in particular, would be able to adapt. While the Englishman has taken to this system well, there have been teething issues across the backline for Wolves, largely to do with positioning, especially for the full-backs, as we will see next.

Playing as a full-back in a back four usually requires the player to be a lot deeper than he would be as a wing-back, with the winger offering support and additional protection. This transition has been tricky for some of the Wolves players, who have sometimes been caught in positions where they may have been had they been playing in a back three. At other times, this has affected their decision-making in regards to tracking runners. All of these issues are to be expected, and can be erased with work on the training ground, but they do offer opponents openings in dangerous areas.

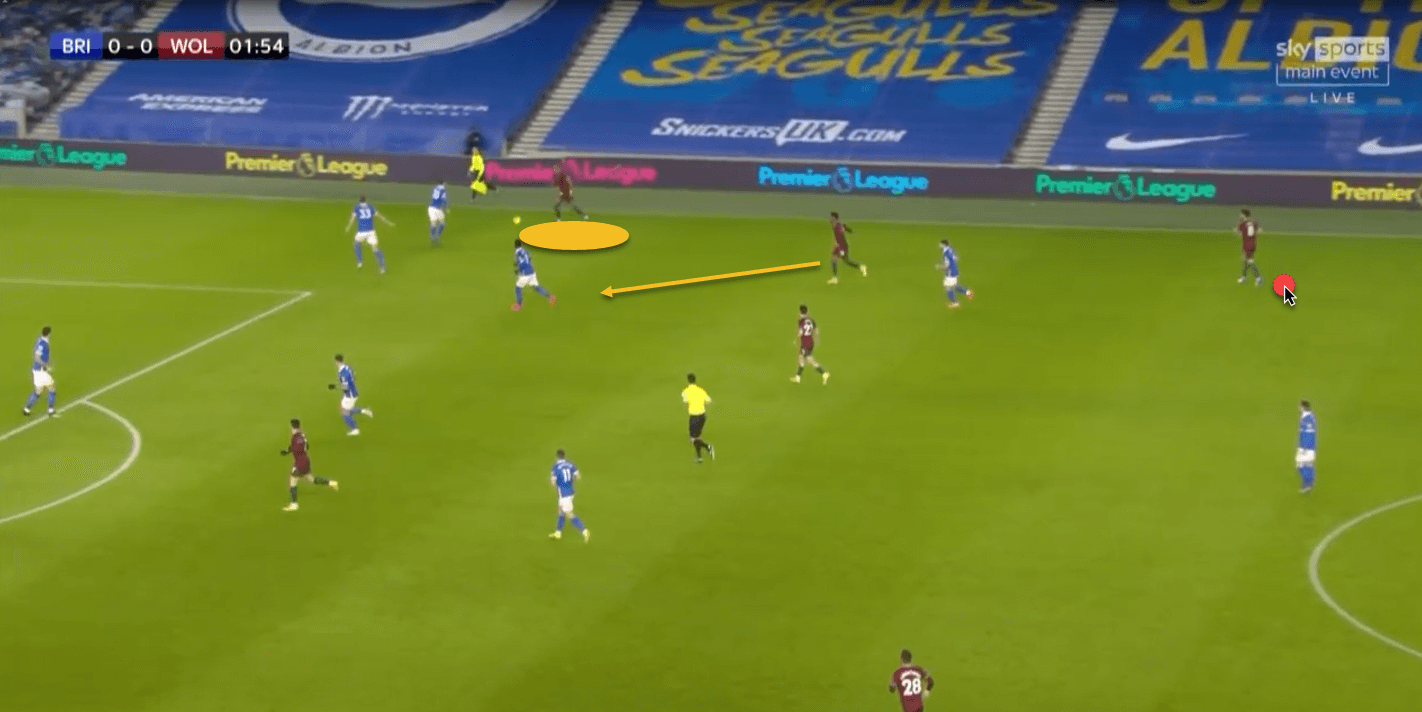

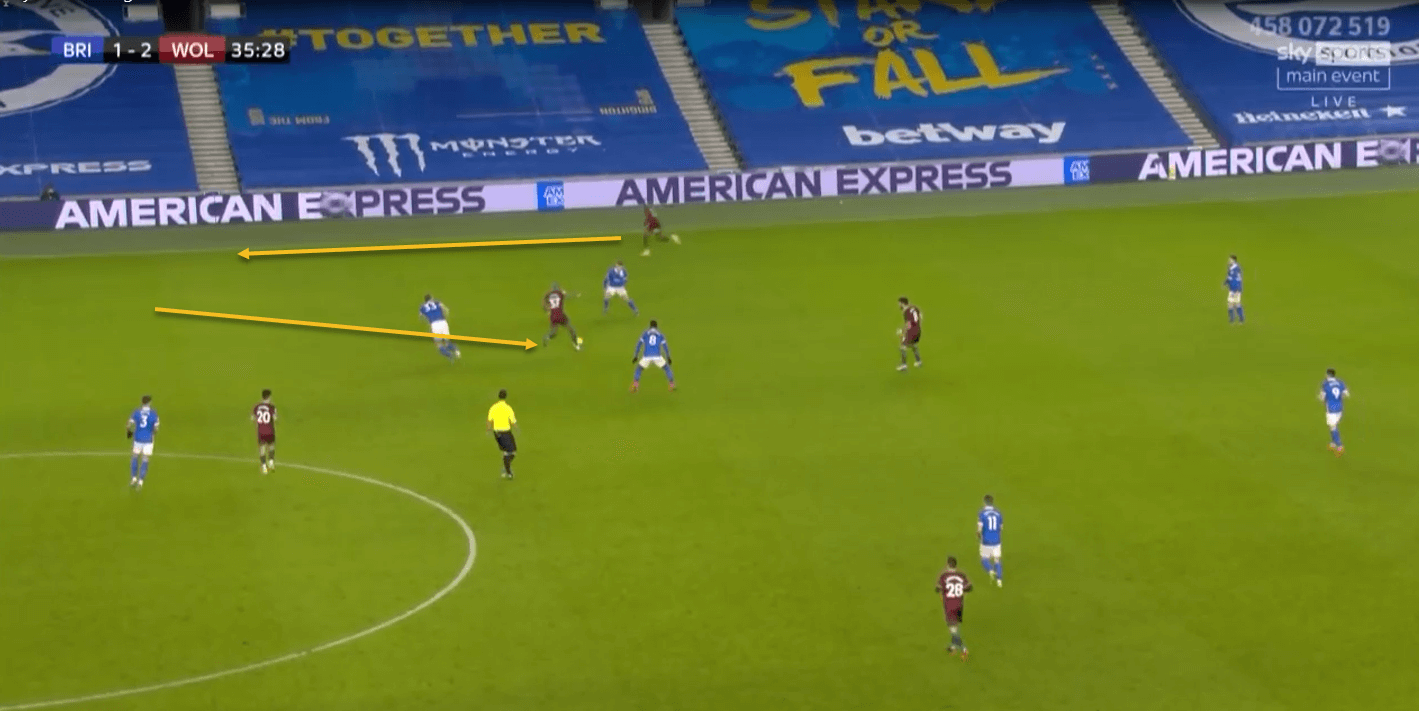

The Wolves backline is narrow here, as expected. However, the midfield is woefully out of position. The line is too high, giving as many as three Brighton players space in between the lines. There is an argument to be made that the defensive line is too deep – in any case, the space between the lines is too great. There is also too much space in front of them, with Yves Bissouma having all the time in the world to be able to pick a pass out to Solly March on the left, who is also in a lot of space.

This is, to an extent, the result of playing against a back three with wing-backs, as Brighton deployed in this game. Nevertheless, it also shows that the midfield and defence were uncertain as to how high or deep they should be, and this was the result.

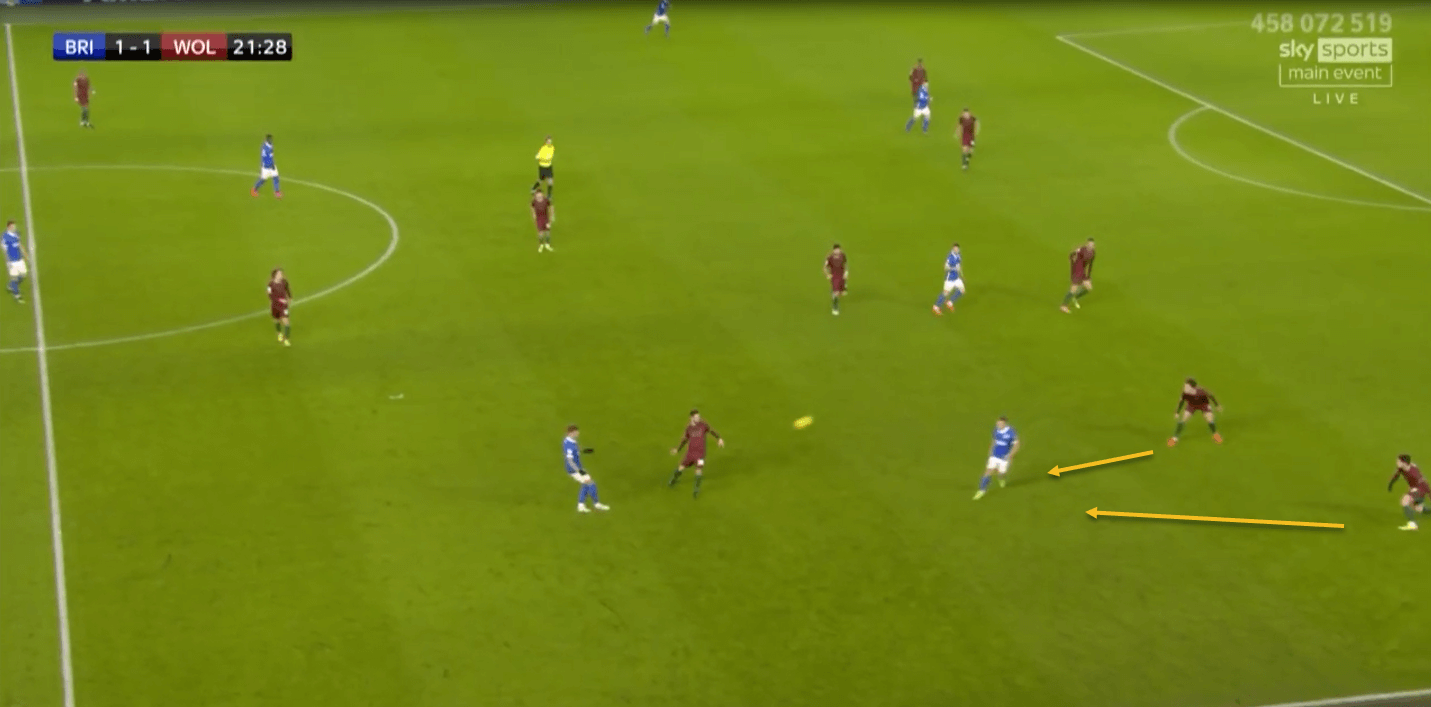

Here, we see an example of runs in behind not being tracked. Both Pedro Neto and Aït-Nouri are attracted to Trossard, which allows Ben White to be able to find Joël Veltman, who makes the run behind the defence. Neto should be tracking that run here, with Aït-Nouri picking up Trossard, but they fail to communicate effectively. This can be attributed to the change in shape, since in a back five, Neto would probably be in a higher and central position, with Aït-Nouri responsible for the flank.

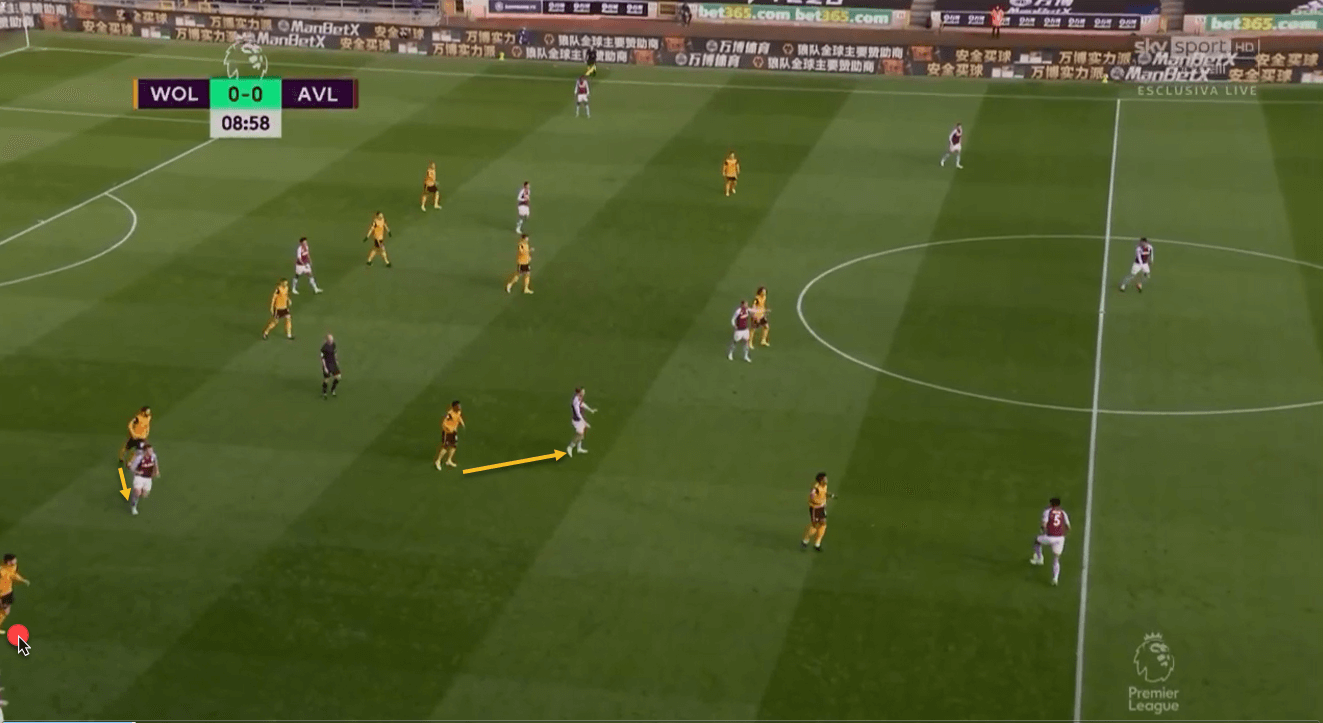

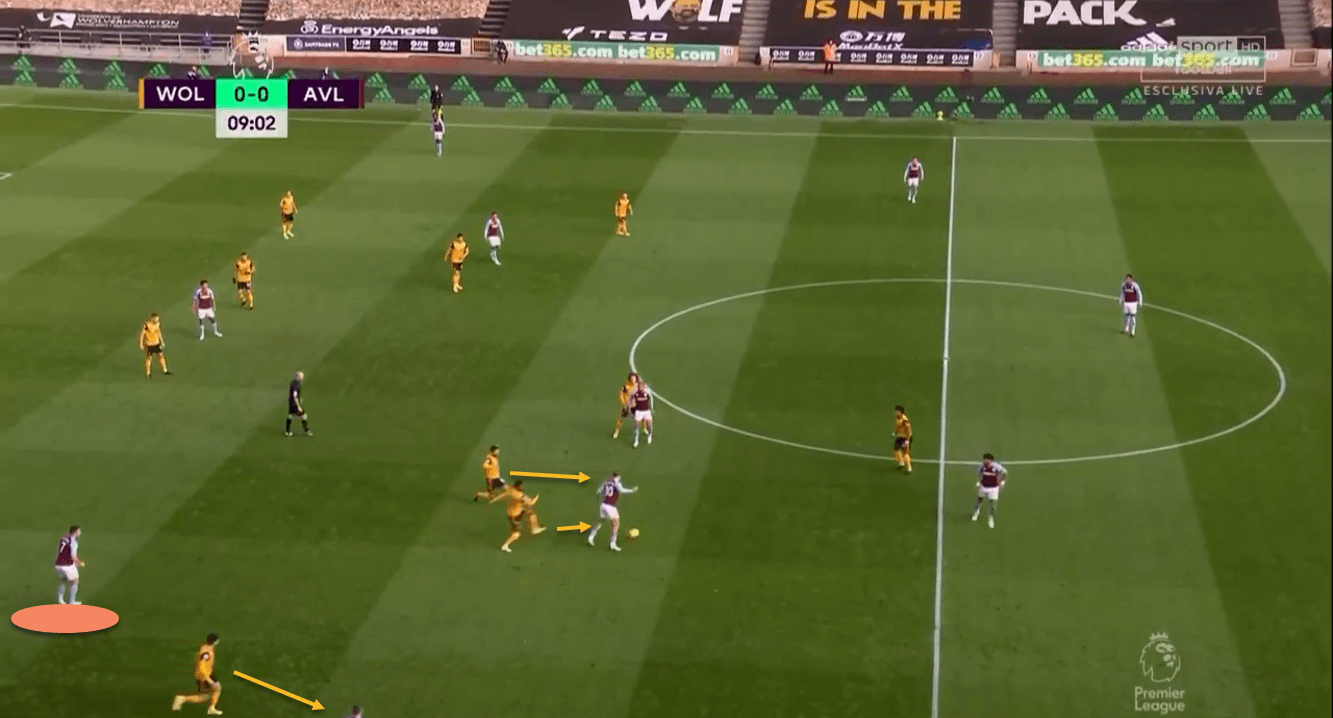

We have another example of wide runners not being tracked effectively.

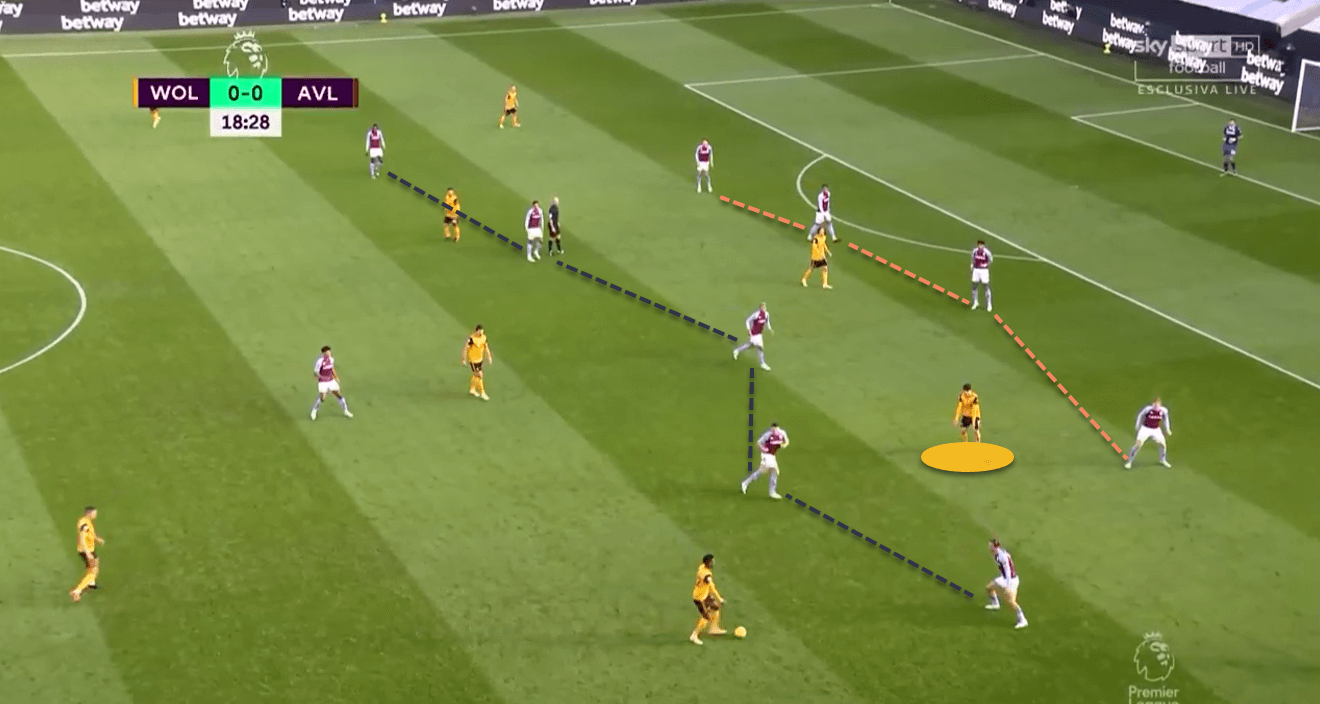

At this time, there is not much wrong with Wolves’ shape. Semedo has moved infield, tracking Jack Grealish, while Moutinho has dropped into the backline while following John McGinn from midfield, and Neto is in the right-back zone (red marker) to pick up Matt Targett.

However, a mistake occurs as the move develops. As the ball is played into Grealish, both Semedo and Moutinho rush to close him down. While this is somewhat understandable given the Villa captain’s threat and influence, it leaves McGinn completely free in a very dangerous position, with Neto unable to move to cover him due to the presence of Targett. Here, again, we see a little bit of disorganisation between the midfield and defence, which could have cost Wolves dearly if Villa had found the pass to McGinn.

The first goal that Wolves conceded against Brighton can be directly attributed to a lack of communication between the centre-backs, as well as the change in shape.

When the ball is delivered from the right, Aaron Connolly has managed to find himself unmarked in the box, despite the presence of three Wolves players in his immediate vicinity. Coady is concerned with Neal Maupay, and Semedo is picking up March, but Moutinho has let Connolly run off him, while Saïss is caught ball-watching and is unaware of what is going on behind him. The Moroccan could have been forgiven for thinking that Coady was mopping up behind him, as would have been the case in a back three, but this was still an error of judgement which allowed Brighton to take the lead.

Conclusion

It is impressive that Nuno elected to switch systems during the course of this, of all seasons, where sustained time on the training ground has been hard to come by. Wolves have done well enough in their new shape – their attacking fluency and threat has definitely improved, even if this has not directly been translated into goals yet. However, the defensive side of things is taking a little more time to settle, and individual mistakes have cost them in a few games. The gamble always was to give up some defensive solidity in exchange for a greater attacking threat, and so, Wolves will need to start creating more clear-cut chances, and taking them, for their switch to a back four to be deemed a success.

Comments