The Manager of the Season award is almost a certainty to fall onto the lap of Arsenal boss Mikel Arteta.

Despite all the jeers and heckling from opposition fans for the Gunners’ recent drop-off in form, which has almost certainly handed the Premier League title to Manchester City, the Spaniard has raised the expectations at the Emirates Stadium to the highest peak in two decades.

However, there is another Spanish coach who deserves a shout for the esteemed award – Julen Lopetegui.

The former Sevilla boss took over at Molineux at a difficult time in the season.

Wolves had sacked Bruno Lage after a horrific spell of form and were staring down the gut-wrenching barrel of relegation heading into the winter World Cup in Qatar.

However, with three games to spare, Lopetegui guided the West Midlands club to safety, picking up 30 points from his first 20 matches in charge, putting an end to the supporters’ anxiety.

Wins against Liverpool, Tottenham Hotspur, Chelsea and Aston Villa were among some of the team’s very best victories in recent seasons and so it’s time that we dissect how Lopetegui pulled the club from the depths of despair to safety within a matter of months.

In this tactical analysis piece, we will analyse Julen Lopetegui’s tactics during his time with Wolves, looking at the highs and lows of the coach’s tenure so far and what needs to improve heading into next season.

Change of shape and direct balls from deep

Before we begin our analysis of Wolves’ tactical set-up over the past few months, it’s important to mention that Lopetegui hasn’t innovated at Molineux. His tactics have not been outside the realms of normality, nor has he managed to wholly recreate the composition of his Sevilla squad which achieved European glory.

Nevertheless, having taken over midway through the campaign, this was never the aim. His objective was to implement a style of play that would see an instant turnaround in results which has been admirably attained.

With a full pre-season under his belt, the typical Lopetegui blueprint may become more apparent next season. But for now, the manager had to work with the tools he was given, and may we say, he’s done some wonderful crafting with them.

Prior to his arrival in English football, Wolves were primarily set up in a 4-3-3 formation as this way, Lage could shoehorn summer signing Matheus Nunes, Rúben Neves and João Moutinho into the midfield all at once, although it wasn’t uncommon to see the Portuguese coach deploy a 4-2-3-1 either.

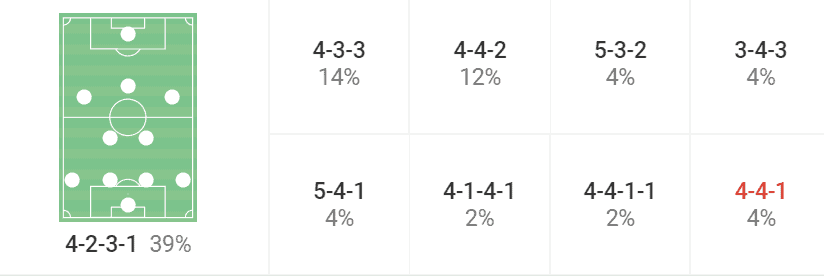

As can be seen from this data viz taken from Wyscout, the 4-2-3-1 has been Wolves’ favoured formation this season in all competitions, across all managers, including interim boss Steve Davis who took temporary charge from the beginning of October through to the start of the World Cup following the early and unsurprising dismissal of Lage.

Once seated in the dugout, Lopetegui stuck with the 4-2-3-1 but had a tendency to switch to a 4-4-2 as well despite being a staunch lover of the 4-3-3 during his three-year spell with Sevilla. The new boss wasn’t too concerned about where Nunes would fit in the middle of the park and has regularly used him on the flanks.

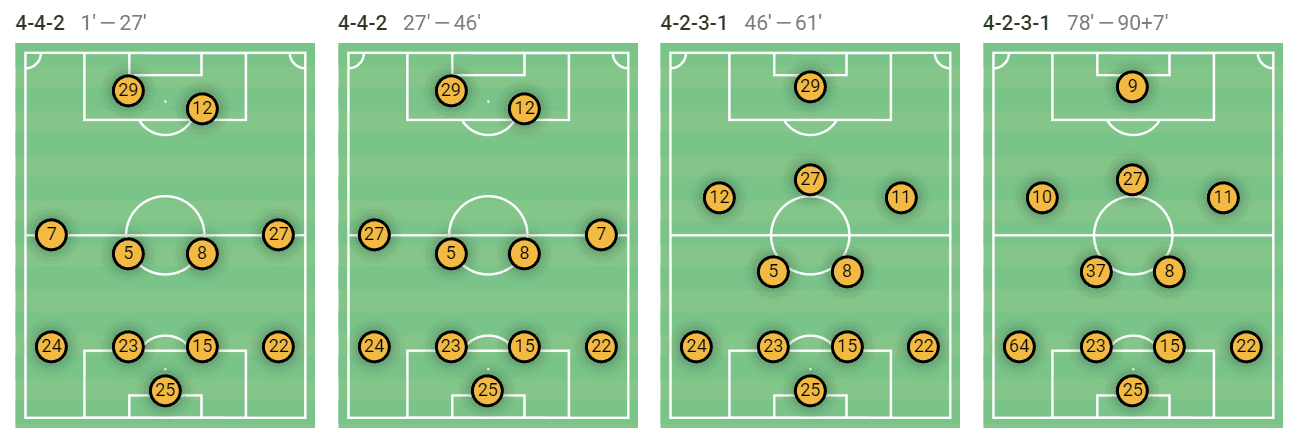

The manager has also been known to shift through the two conventional structures in-game as was made apparent from the side’s recent 2-0 defeat against Manchester United in which Lopetegui decided to revert to a 4-2-3-1 in the second half after going a goal down.

This change was wise. Having used Matheus Cunha in a strike partnership with the ex-Chelsea man Diego Costa, Lopetegui wanted the former to play more as a number ‘10’, dropping deep, pulling Man United’s defenders out of position which would have created more space for the wingers and Costa.

On a technicality, the change did work, although perhaps not to the extent that Lopetegui would have wanted as Wolves still couldn’t find the net.

Nonetheless, the team had more stable possession in the second half after some up-and-down periods before the interval. Furthermore, three of Wolves’ four shots came in the second half too as a result.

Unfortunately, the Wanderers didn’t score but at least troubled the Red Devils more so than in the first half, causing a nervy atmosphere to enter into Old Trafford before the returning Alejandro Garnacho eventually sealed the three points for the hosts.

Regardless, formations are not the be-all and end-all of Lopetegui’s tactics. The Spaniard’s principles are far more layered than what Pep Guardiola once described as mere ‘telephone numbers’.

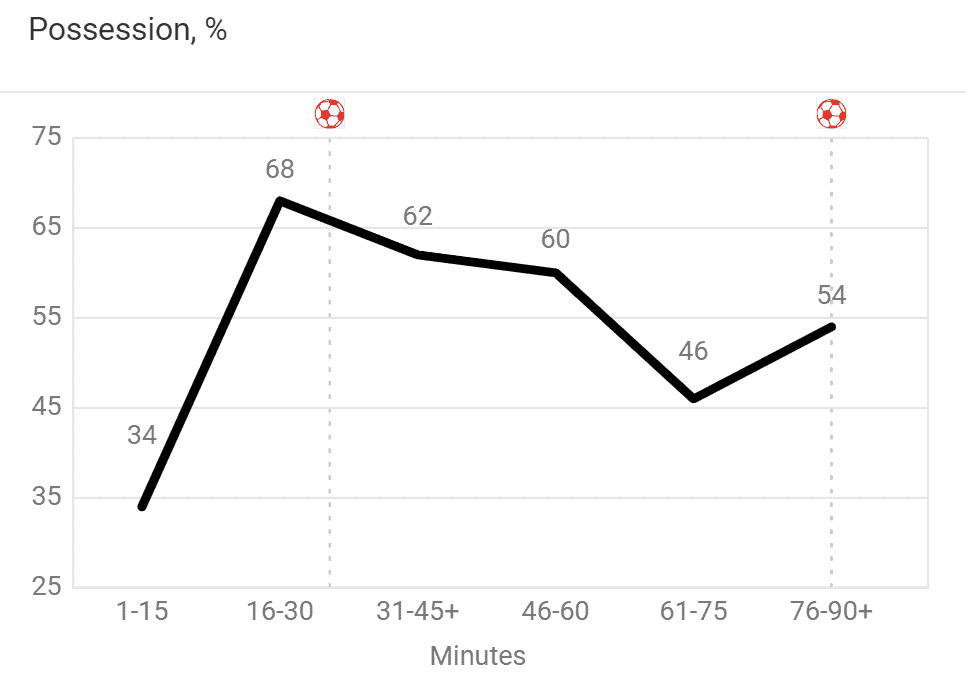

Expectedly, Lopetegui wants his team to play out from the back. They build with the fullbacks positioned low while the centre-backs split the goalkeeper and the double-pivot sit behind the opposition’s first line of pressure.

Quite often, one of the double-pivot will drop between or beside the two central defenders, basically becoming a third centre-back on occasions where the opposition press with a two-man front line. This way, Wolves can create a 3v2 against the first line of pressure and the fullbacks can advance on the flanks as a result.

There is no obvious route of progression for Wolves. The backline circulate the ball from side to side, forcing the opposition to switch from a high block to a mid-block.

However, where his Sevilla team would build through the pivot in Lopetegui’s 4-3-3, Wolves prefer to play down the flanks, often using the pass from the fullback to the ball-side winger as the source of breaking through the opposition’s initial press.

But this can be problematic as sometimes the opponent’s wide defender can read the play easily and intercept, starting a transition high up the pitch.

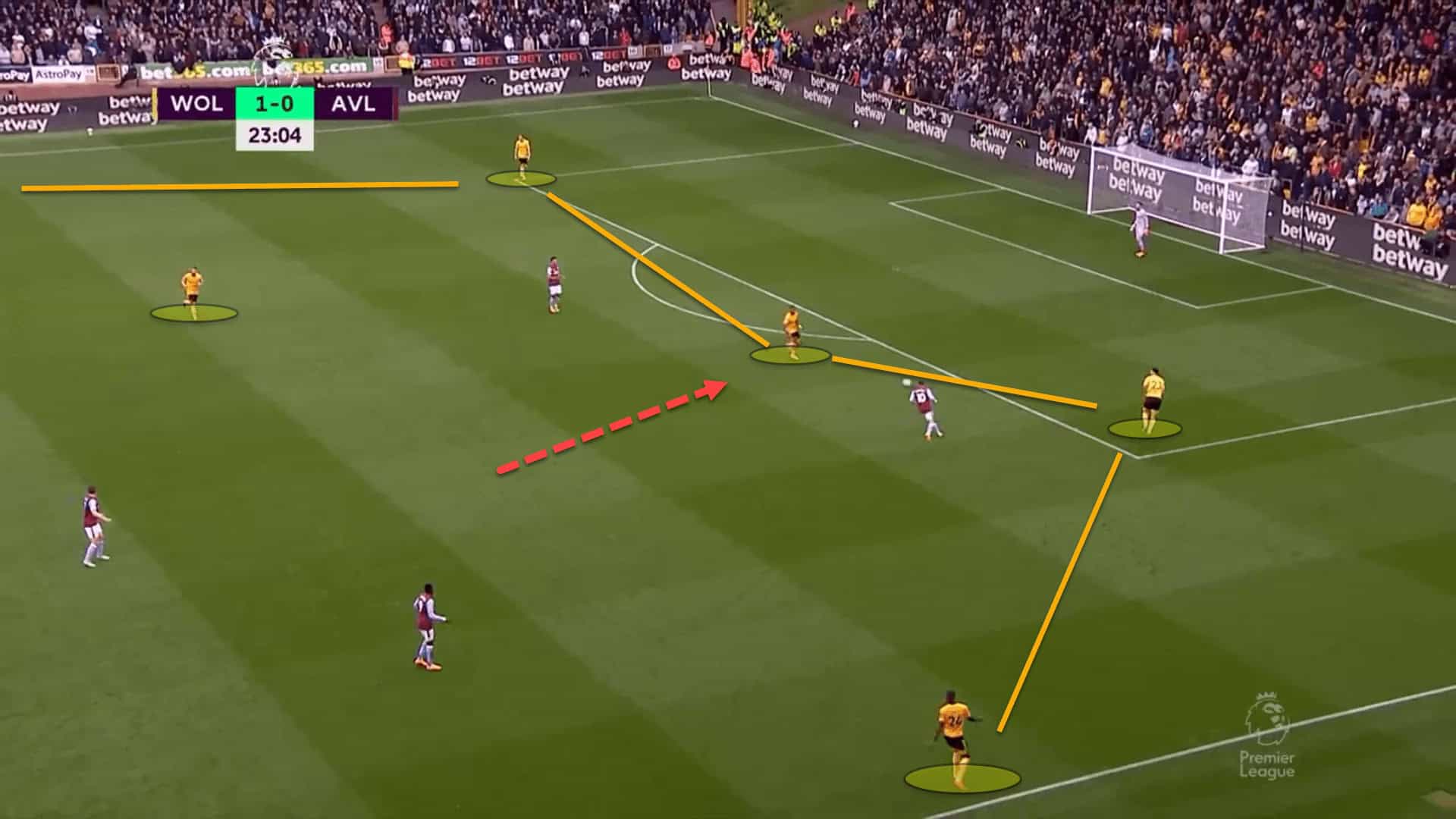

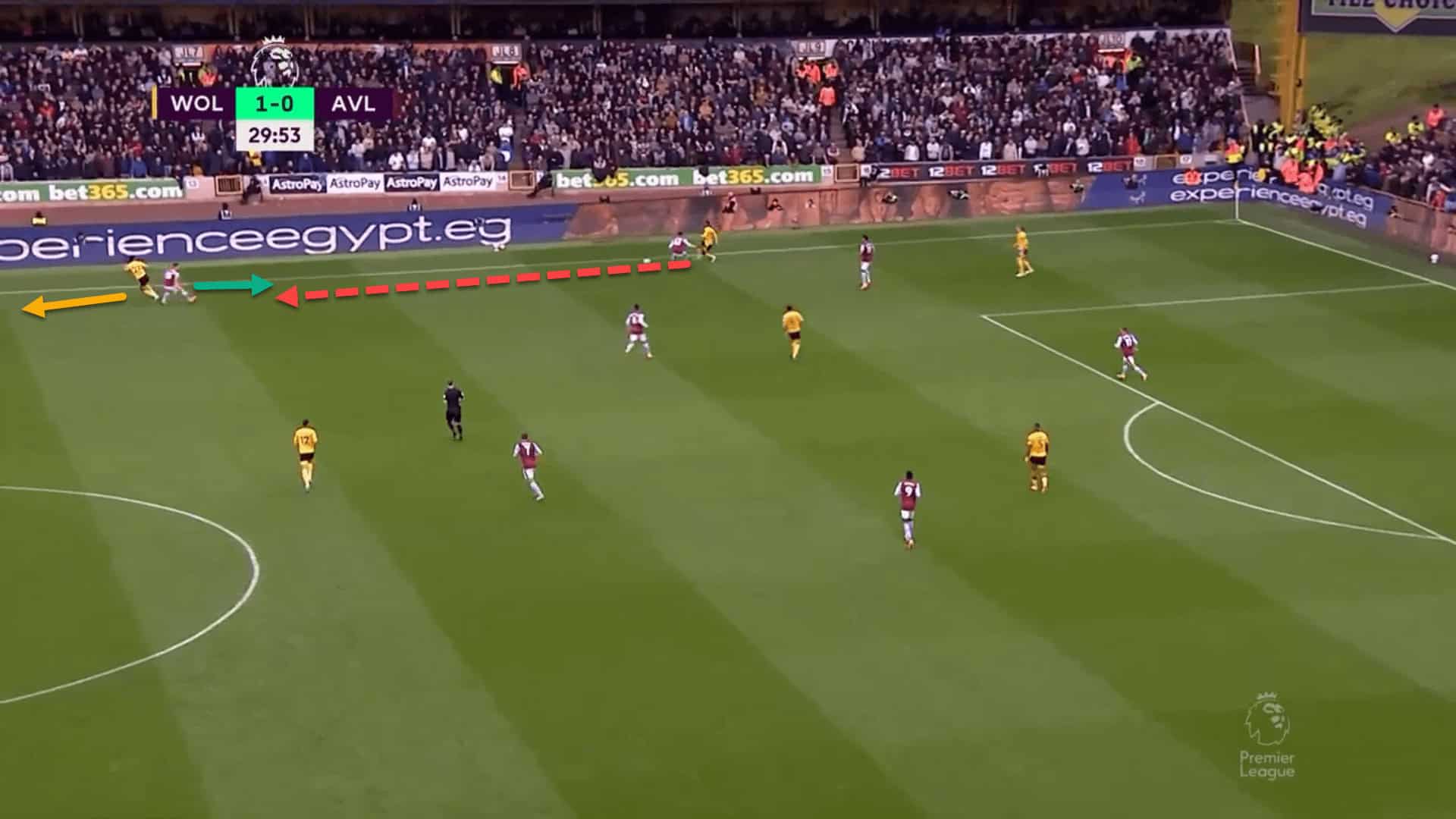

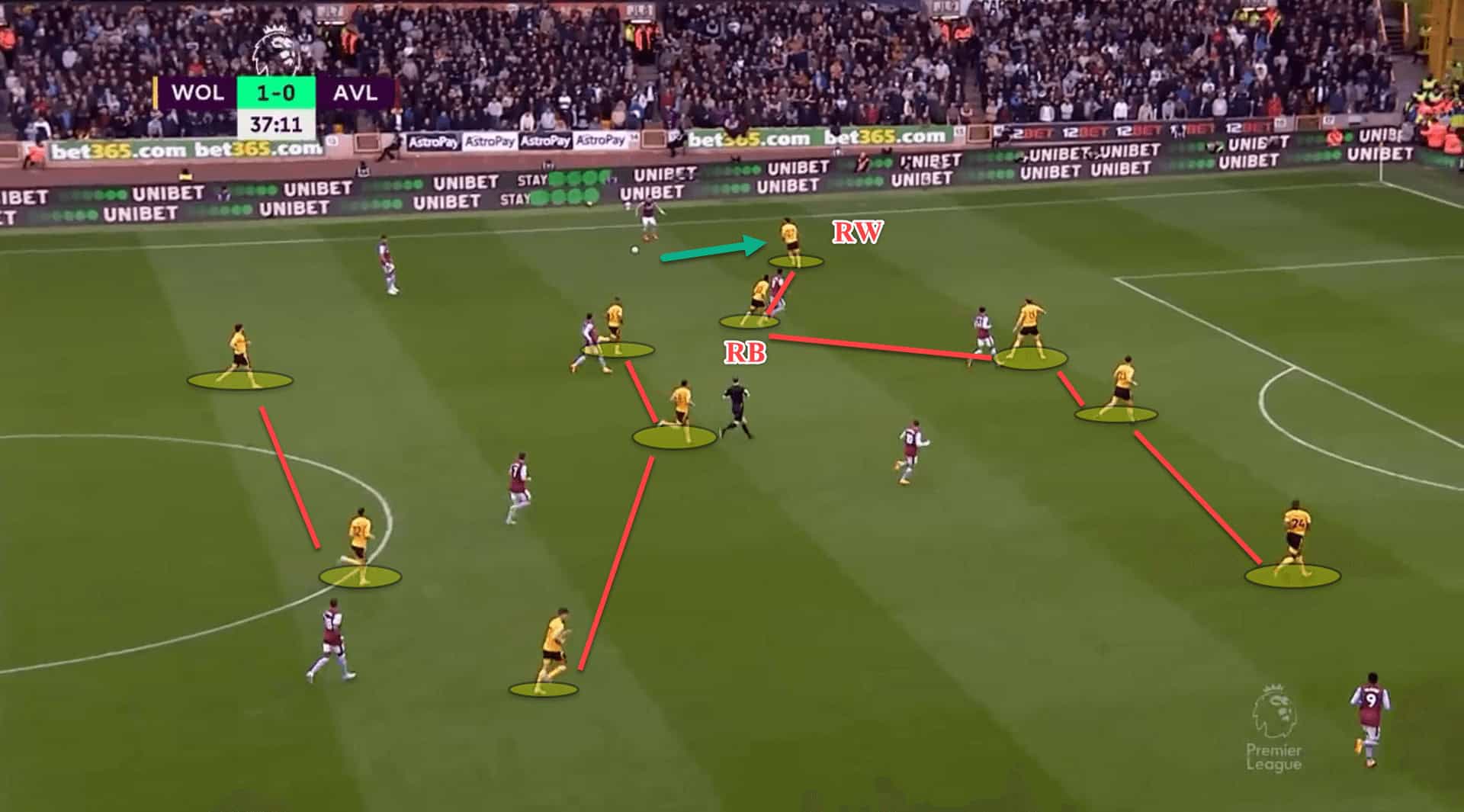

Here, right-back Nélson Semedo attempted to find Nunes who was playing on the wing.

Nunes believed that his teammate was sending a channel ball down the line but the pass was indeed short which allowed Aston Villa’s left-back to nip in and begin a counterattack for the visitors in Wolves’ half of the pitch.

It is also customary to see Lopetegui’s side go long to the frontline. Mario Lemina and Neves aren’t exactly press-resistant players and so can be jumped from behind when they receive, hence why Lopetegui wants his double-pivot to get the ball in the backline where they will have more time and space to pick a pass.

This can be listed as the reason why the manager has asked his players to try and avoid building through the midfield.

The front two of Cunha and Costa have worked well in recent weeks at playing off one another from these direct balls from the backline.

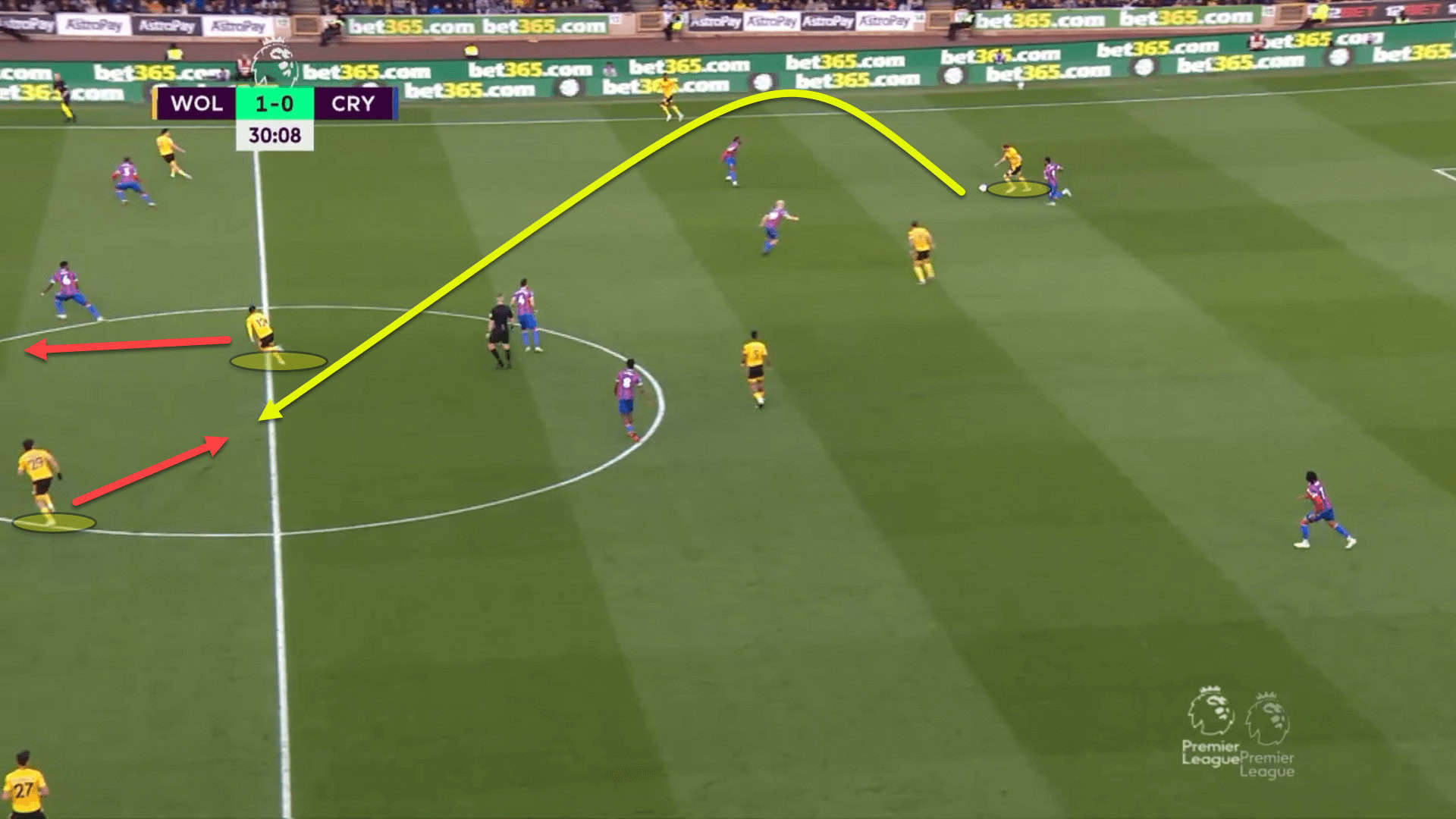

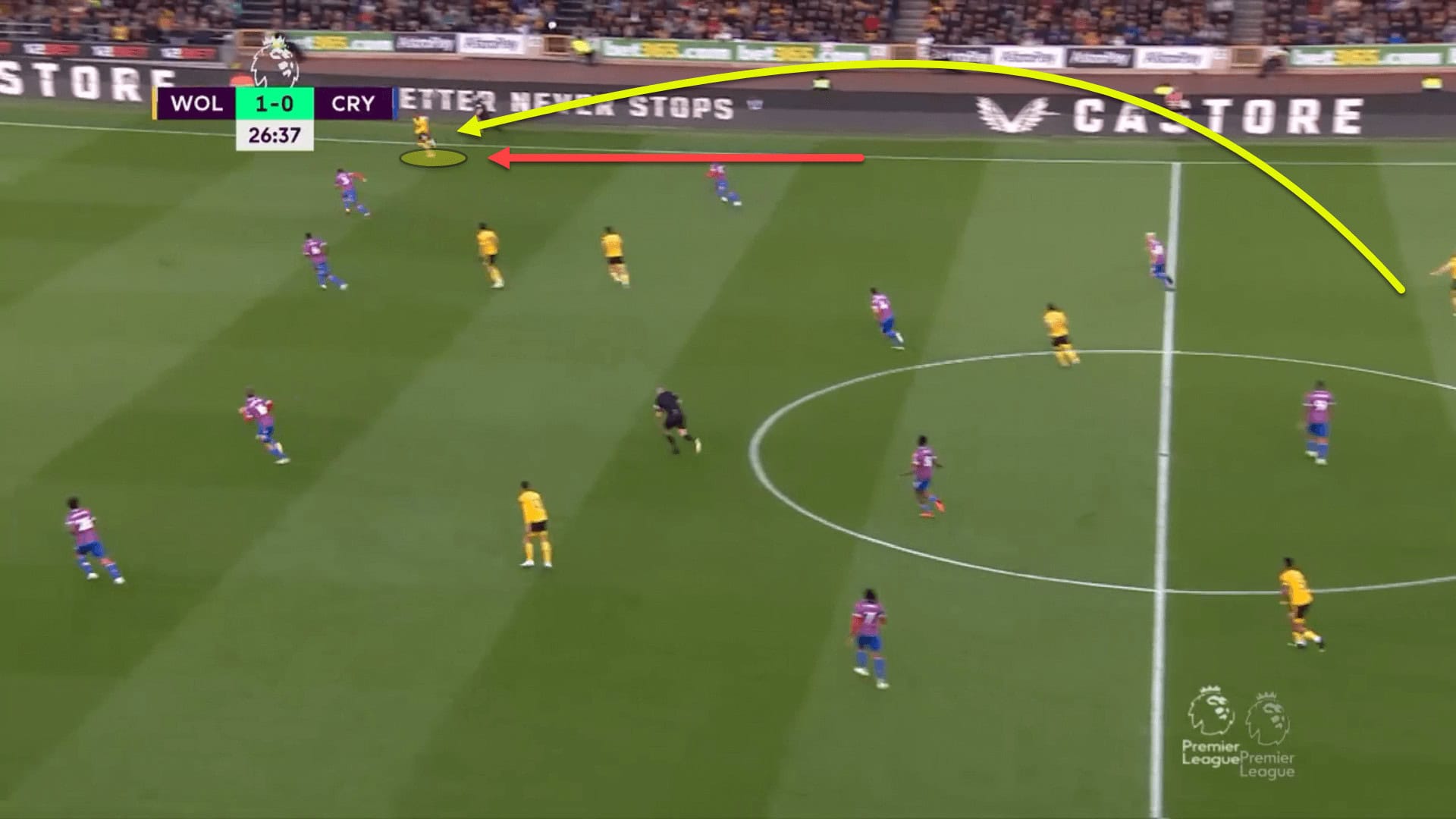

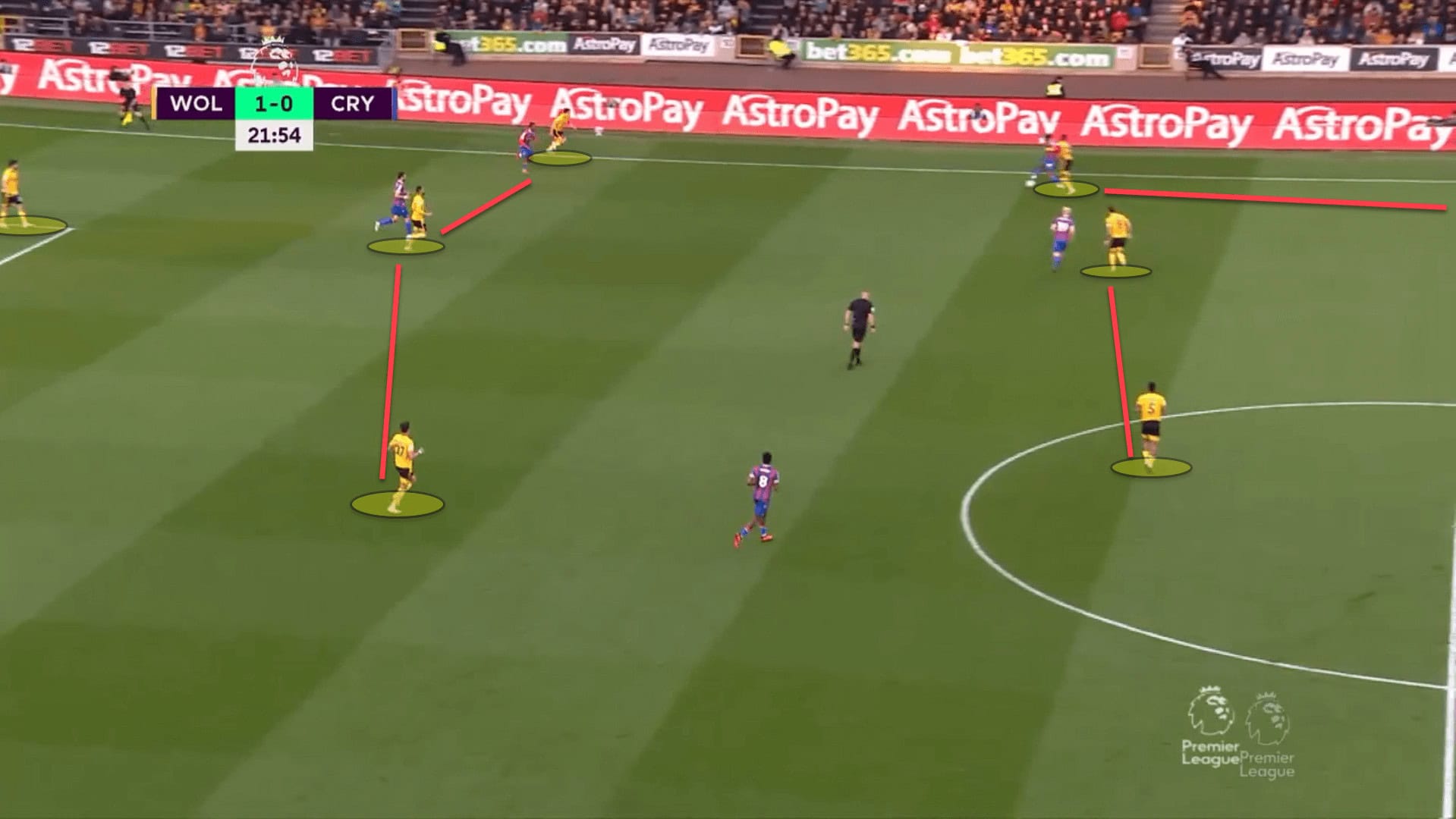

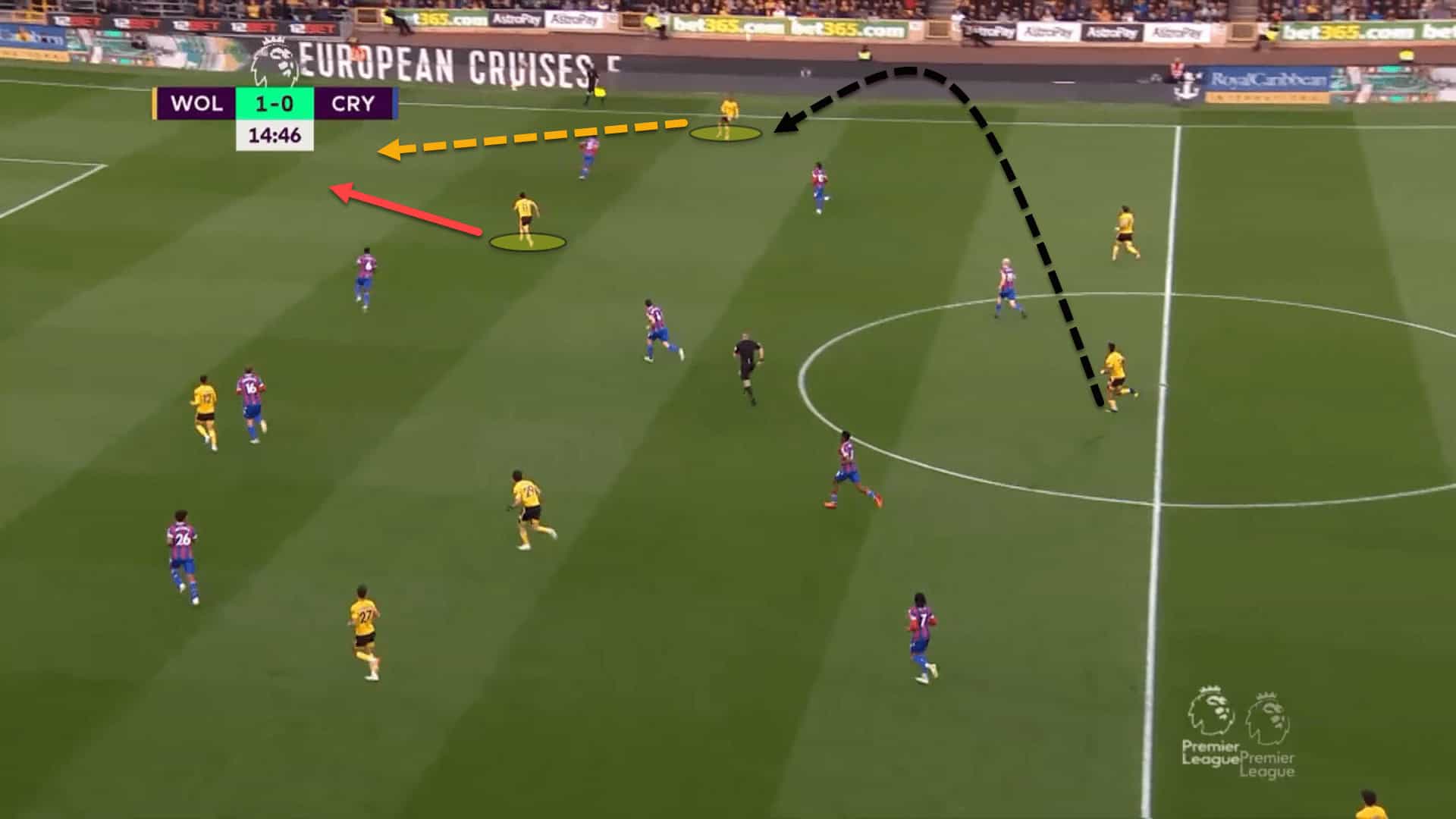

In this example against Crystal Palace, Craig Dawson oriented his body to go long.

Cunha noticed this and began darting in behind the Eagles’ defence while Costa moved centrally and a little deeper.

This is called a countermovement as the duo moved in opposite directions to disorientate the backline. If Costa flicked it on to Cunha, Wolves would have been in on goal.

Costa couldn’t control the ball and possession was overturned but it was a good example of how Wolves can cause danger from direct balls over the press rather than playing through it.

Breaking down a deep block

During the build-up phase, Wolves’ formation is quite telling. The fullbacks are low, the wingers are wide and the front two are normally playing off the shoulder of the opposition’s centre-backs.

However, it’s further up the pitch where the base formation loses all resemblance to itself when the West Midlands club are trying to break down a mid-to-low block or an outright low block. This is often called the second phase or even the progression phase.

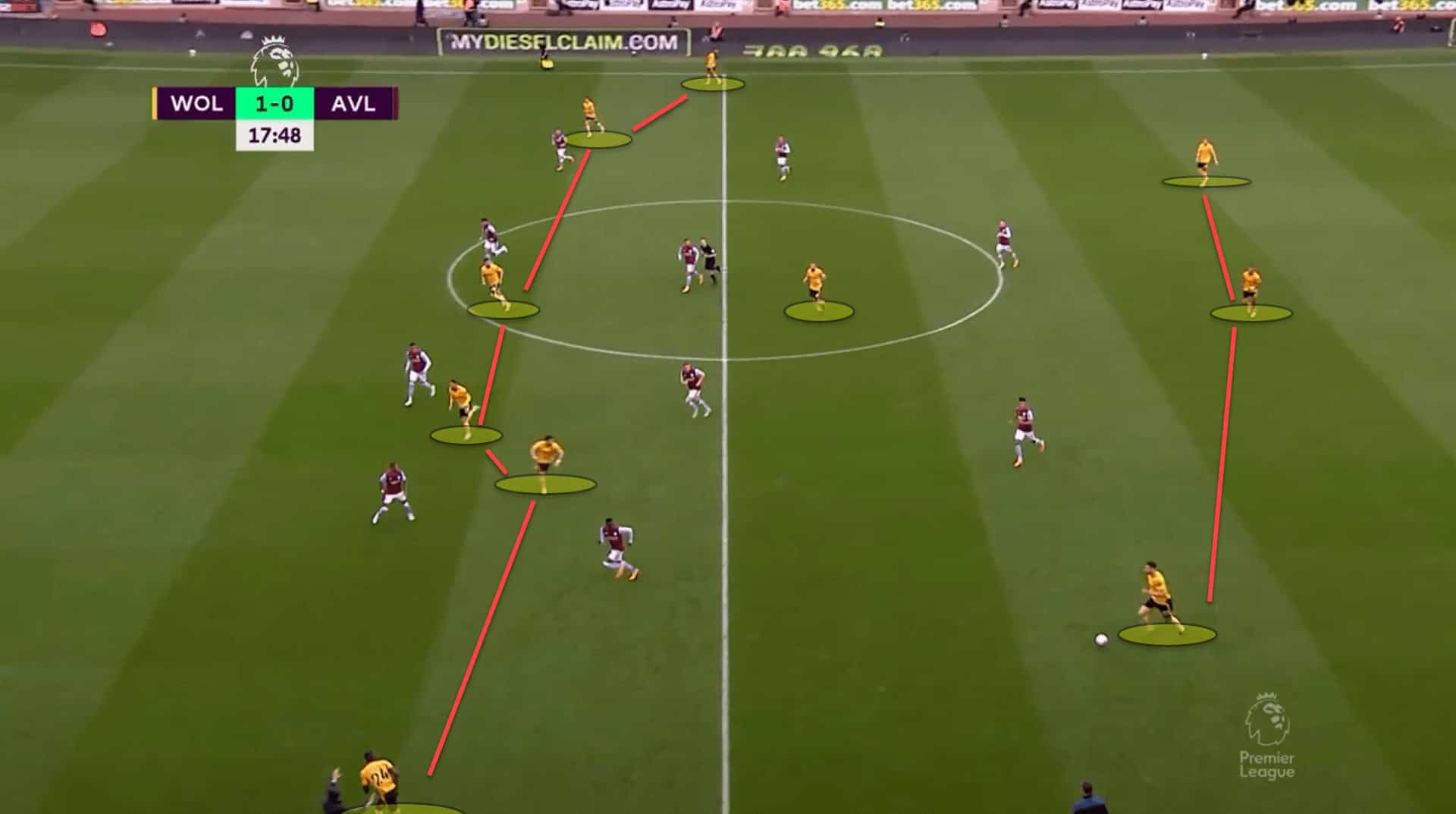

Wolves’ structure switches from a 4-4-2 or a 4-2-3-1 to a 3-1-6. Similarly to the build-up phase, one of the double-pivot drop into the backline to create a 3v2 while also giving themselves more time and space to pick out a forward pass.

Both fullbacks get forward on the flanks while the wingers tuck inside into the halfspace, either playing inside or outside the opposition’s fullback.

As aforementioned in this scout report, Lopetegui’s team rarely play through the midfield, hence why so many bodies are committed forward.

He wants his last line to attack the depth as much as possible to take advantage of the space behind the backline.

This is particularly useful against a mid-block as there is a lot of room to run into, which is evident from the previous screenshot.

Wolves switch the play a lot during this phase too.

The back three, including the dropped pivot player, are important to do this.

These three players will circulate the ball among themselves, hoping to lure the opposition’s block to one side of the pitch before then switching it out to the highly-positioned fullbacks.

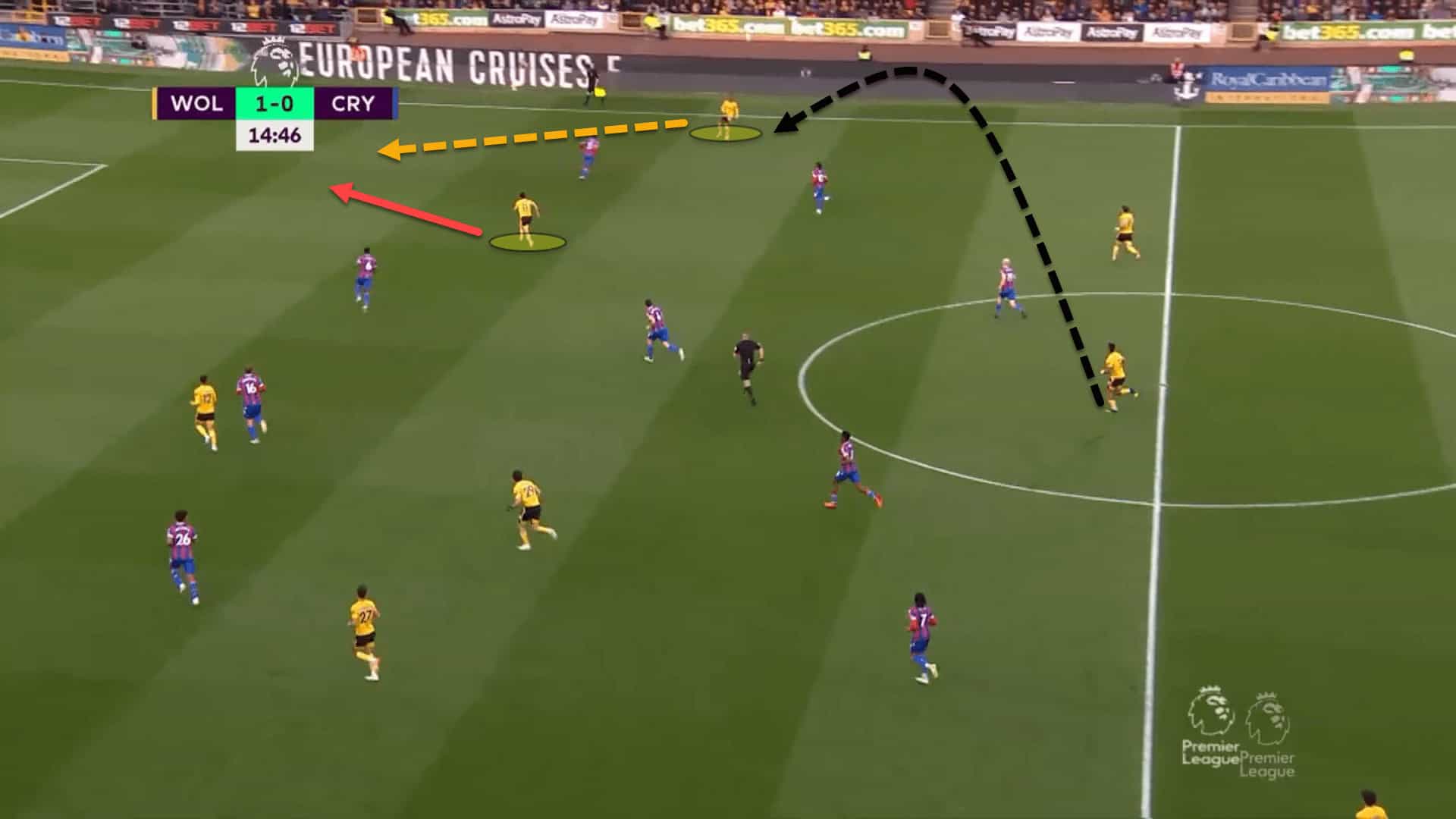

Here, Palace’s mid-block was skewed slightly to one side as the ball was over in the left halfspace.

Knowing that they wanted to quickly switch the play to the right as there was space over on that side, Lemina played a fast-paced ball over to Craig Dawson who had already scanned over his shoulder to see Semedo in space.

The next pass was directly to the Portuguese fullback who had made a flying run down the wing, expecting the ball before it had even reached Dawson’s feet.

Developing this even further, the fullbacks link up nicely with the inside winger. Once the ball is switched out to the wide defender, the winger knows he needs to make a run in the channel between the opponent’s fullback and the nearest central defender.

The reason for this is that the opposition’s fullback will step out to mark his counterpart, opening the channel to his covering central defender.

In the previous screenshot, Semedo had received from the switch and Hwang Hee-chan had made this move.

The former Barcelona man was able to get the ball out of his feet and find the South Korea international with a slipped-through pass on the fullback’s blindside. In turn, Wolves reached the final third and were in a decent crossing position.

Already, we can notice differences between this Wolves team and Lopetegui’s Sevilla.

The latter were far more patient with the ball, whereas the former are a little more direct, relying on channel runs, switches and crosses. But they are/were equally as effective for their respective squads.

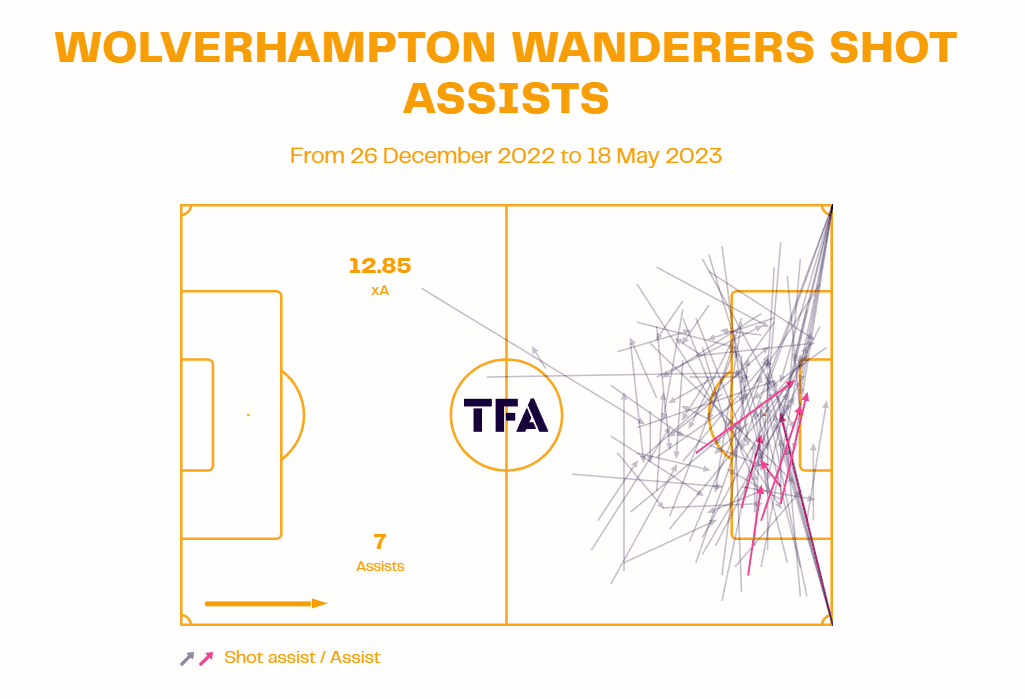

Crossing has been Wolves’ primary source of chance creation under Lopetegui, both from open play and set-pieces situations.

This data viz displays all of Wolves’ shot assists since the Spanish coach took the reins during the winter period.

Shot assists are registered when a pass leads to a shot on goal. As we can see, so many of Wolves’ shots come from crosses from the wide areas and corners.

However, it should also be noted that the team have registered 7 assists in all competitions from an expected assists of 12.85.

Does this mean that the balls into the penalty area have been of inadequate quality or have Wolves been struggling to find the net due to poor finishing?

Let’s look at what the data says.

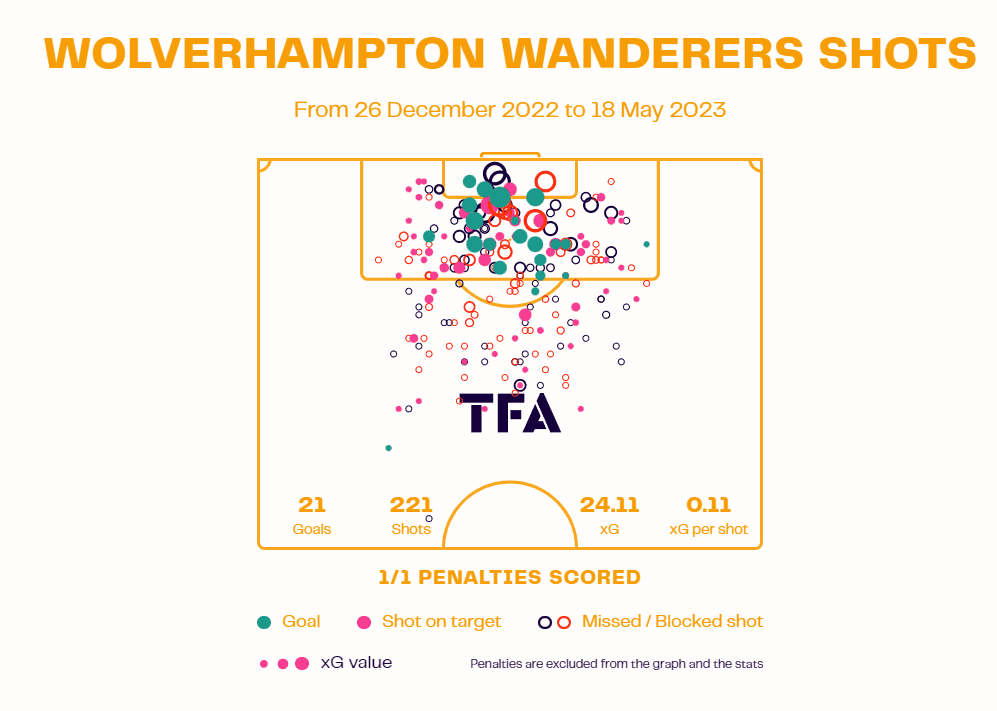

It’s a bit of both. High crosses from the flanks are notoriously low percentage opportunities. Given the number of variables involved such as the flight of the ball, positioning of the centre-forward, intervention from the goalkeeper, distance to goal and a million others, high crosses have a small chance of ending in a goal, hence why Wolves have registered an xG per shot of 0.11 which is quite low.

Under Lopetegui, Wolves have underperformed their non-penalty xG of 24.11, scoring 21 times from non-penalty situations.

But this underperformance isn’t the end of the world. In fact, it’s an improvement from life before Lopetegui.

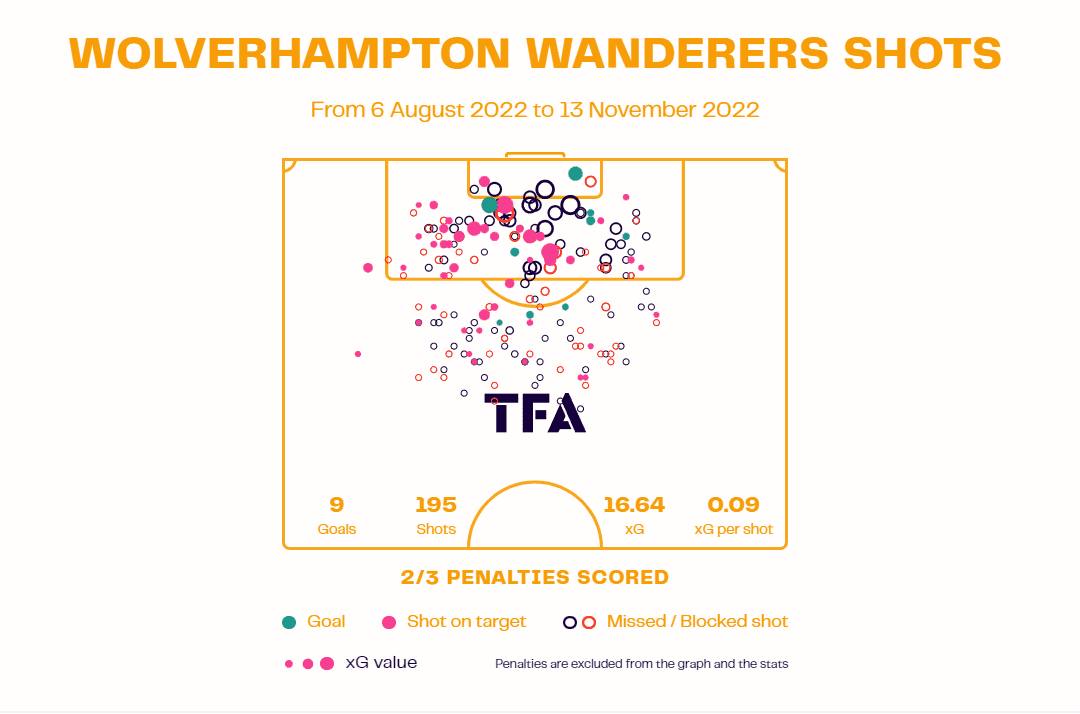

Prior to his appointment at Molineux, the Wanderers were faring much worse in front of goal, scoring merely 9 non-penalty goals from a npxG of 16.64 and the side’s xG per shot was even lower at 0.09.

However, it must still be noted that Wolves currently boast the worst goals tally in the league, even behind relegated Southampton and so it’s something that’ll need to be fixed next season.

There is still a lot that can be improved on regarding Wolves’ attacking play but it’s certainly been an upgrade from before his arrival in the West Midlands which is a success in itself.

Defensive issues

Wolves have been solid defensively during Lopetegui’s reign so far.

The Wanderers have conceded 26 goals in 21 games in the Premier League which isn’t perfect but is certainly better than a lot of teams in the same division.

This comes to roughly 1.24 goals per game in England’s top flight.

They are difficult to break down but also like to engage higher up the pitch when the opposition are building out from the back.

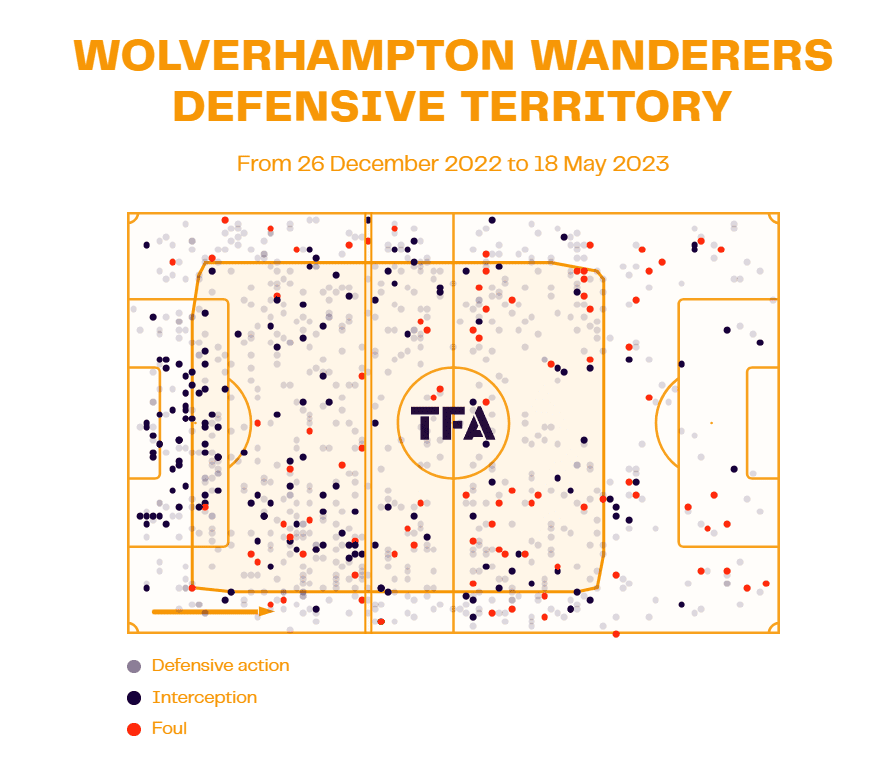

Here is Wolves’ defensive territory map over the course of the Spanish coach’s tenure at Molineux which shows that the team’s average defensive line height is just slightly under the centre circle, meaning Wolves defend in both a mid-to-high block as well as an outright high block.

There is nothing unorthodox about how Lopetegui sets his side up to press the attacking team.

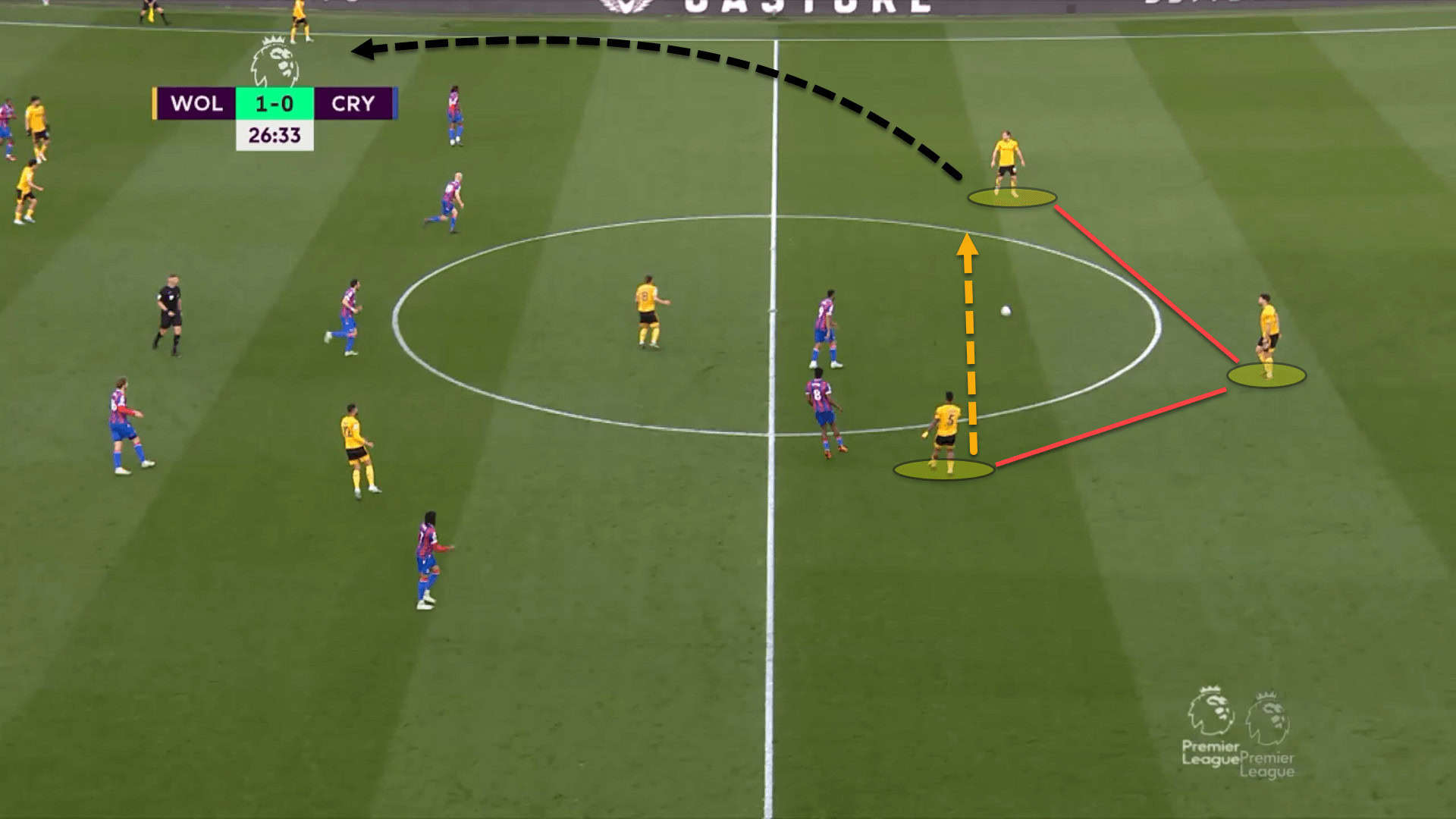

The first line of pressure lead the press, angling their runs to force the opposition’s centre-backs to play out wide in a process that is often called ‘splitting the opponent’.

Once the ball is moved to the flanks, Wolves defend man-for-man on the flanks, using the touchline as an extra man to make life uncomfortable for the opposition and to potentially reclaim the ball in a higher area.

Once the press is broken, Wolves are instructed to immediately drop into a compact 4-4-2 shape.

Sometimes this structure falls into a 5-3-2 as the ball-near winger is tasked with marking the opposition’s advancing fullback while Wolves’ own fullback takes the inside winger.

This also allows the back four to stay closer together which is beneficial for defending crosses.

If the winger didn’t drop into the defensive line, the fullback would be forced to step out to prevent the cross, causing there to be fewer players to defend inside the box.

However, there have been issues with Wolves’ low block that have become apparent throughout not only Lopetegui’s spell in charge of the club but the entire season.

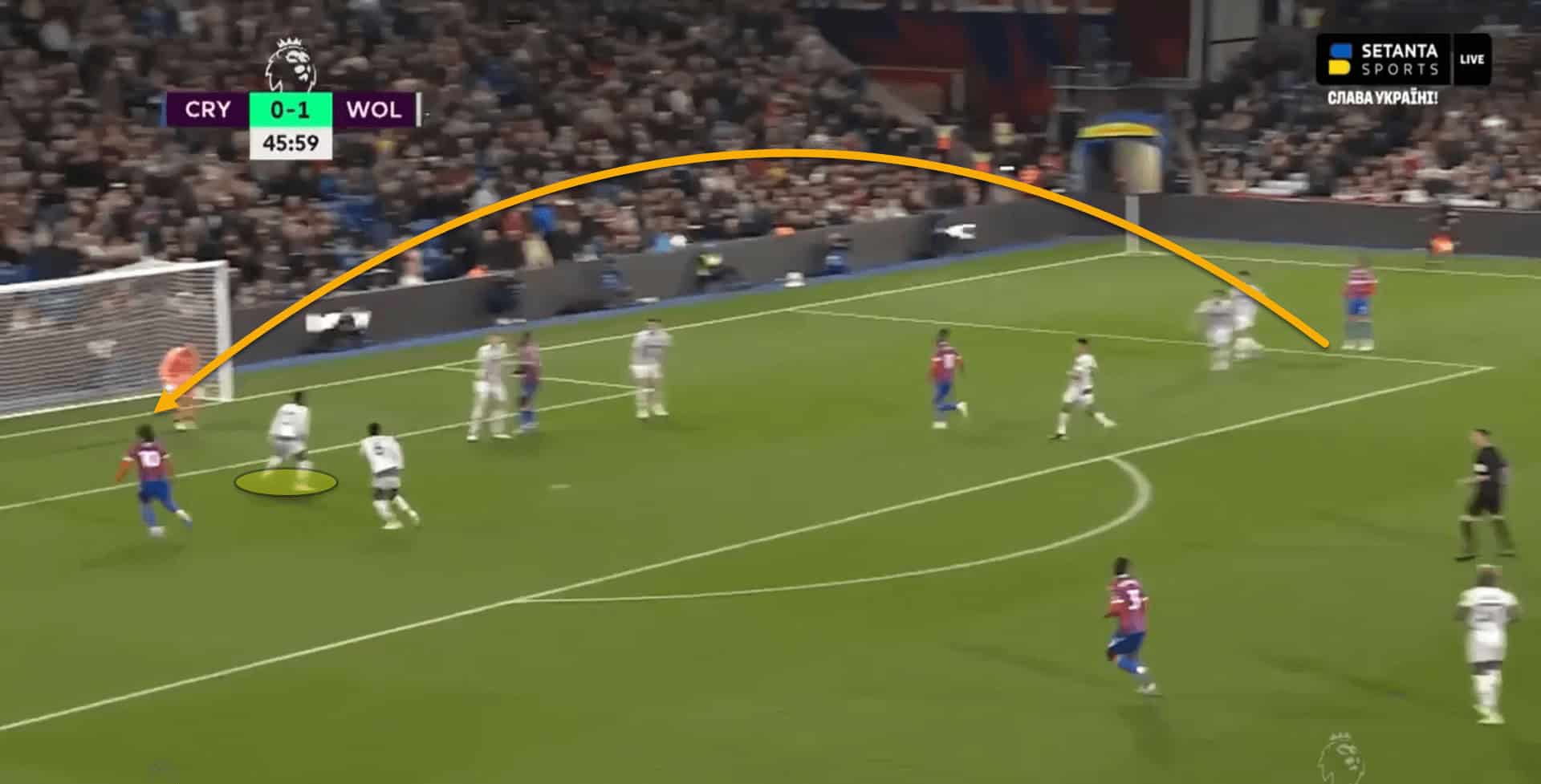

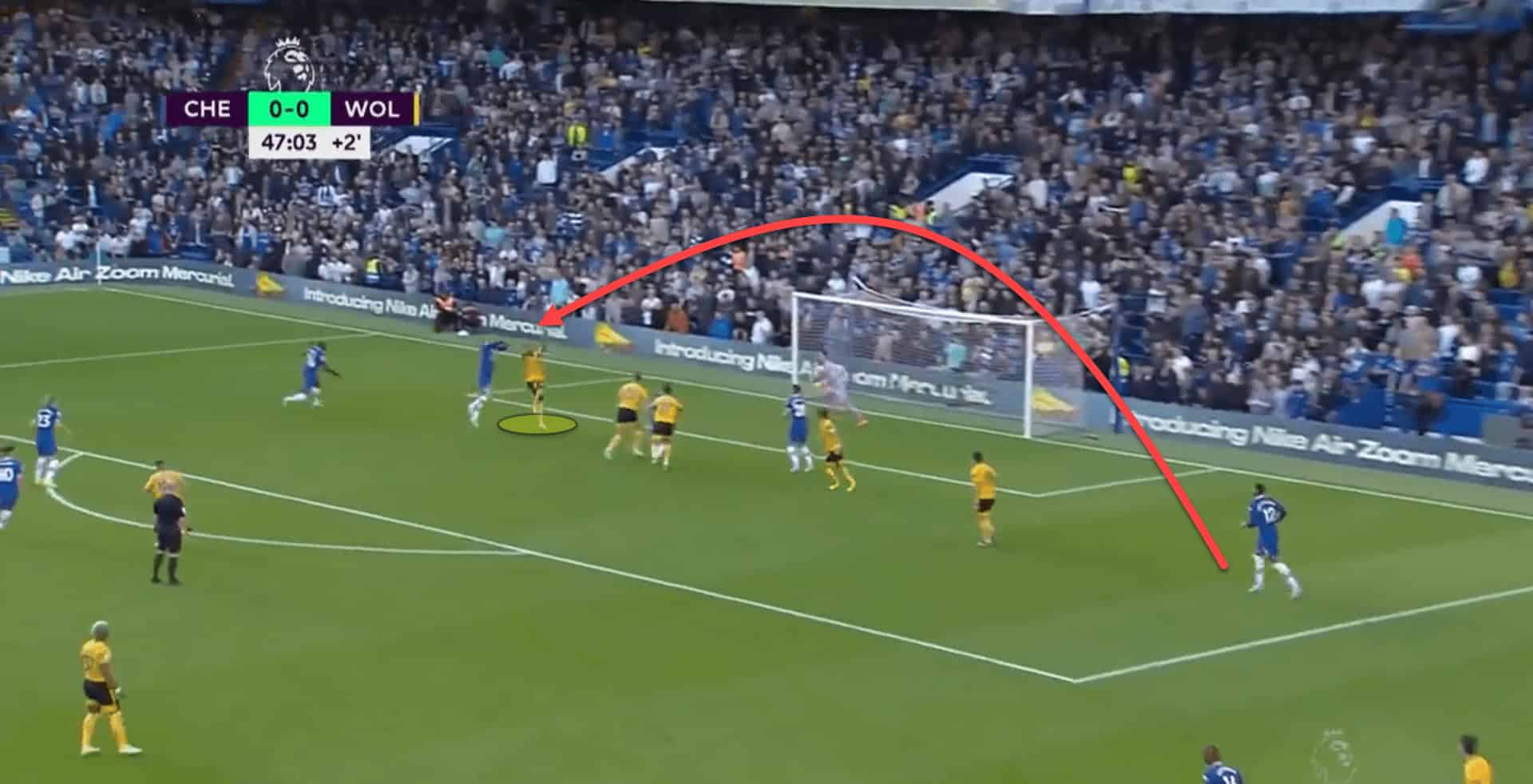

One of these issues has been Semedo’s defensive qualities, particularly his ability to defend his back-post.

Opponents have scored countless goals this season from this very situation, whipping it into the back-stick for someone to outjump Semedo as he hasn’t properly scanned over his shoulder and positioned himself correctly.

Don’t believe us? Let’s pull up some examples.

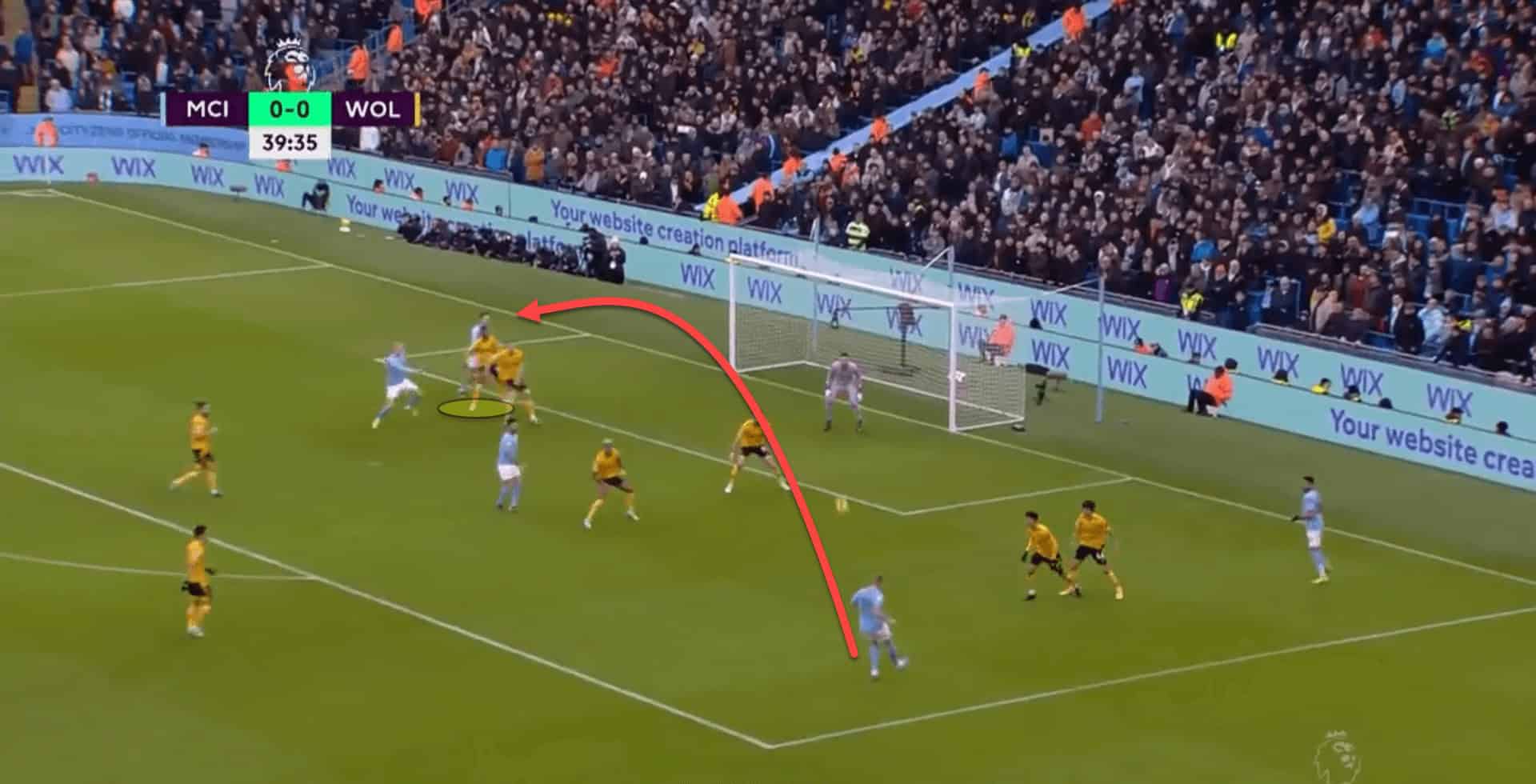

OK, perhaps we’re being a little harsh in the first example as he is up against Erling Haaland after all but it’s no coincidence that Semedo is being targeted in games.

Here are three different examples from three different games across two different managers.

The fullback is a real threat going forward for Lopetegui and the manager has a lot of faith in him in the attacking phase.

Nevertheless, the former Benfica star is causing a lot of problems at the back for the Wanderers and it’ll be interesting to see whether the manager looks to replace his number ‘22’ in the summer, although the club have just triggered the extension clause in his contract as of yesterday which could answer this conundrum for us.

Conclusion

Wolves were anything but wolves when Lopetegui took over.

In fact, they resembled ageing Golden Retrievers more so than predatory, animalistic carnivores in the final third.

But since the Spaniard’s arrival, he has helped Wolves find their roar again, albeit with some voice breaks here and there.

The future is bright and Molineux has fallen back in love with their team again.

Wolves are now safe and it’ll be incredibly interesting to see how Lopetegui improves the squad in the summer and whether they crack on next season.

Comments