Unfortunately, the Women’s European Championship is down to the final game, which will be played this Sunday at the grand stage of Wembley Stadium.

The hosts England ran rampant on Tuesday night, demolishing Peter Gerhardsson’s Sweden with a 4-0 victory at Bramall Lane to seal their place in the final, waiting patiently to find out their opponents on Wednesday as Germany and France locked horns.

The second semi-final was a lot more close-knit, with the two European titans leaving it all on the pitch. However, as cruel as football is, only one team could go through to face the Lionesses this weekend.

France have been a bit of a surprise package in the tournament thus far. Les Bleues are a team filled with quality with an exceptional tactician on the sidelines, but rumours of unrest in the dressing room led many to believe that a collapse was inevitable.

Nevertheless, head coach Corinne Diacre held it together and managed to lead her side all the way to the semi-finals, narrowly losing out to Martina Voss-Tecklenburg’s Germany who have been a resilient defensive wall filled with powerful and potent prowess going forward.

The game was fascinating to watch from a neutral perspective but breaking down the tactics used by the two teams was even more intriguing. This article will be a tactical analysis of the semi-final clash. Through our analysis, we will dive into how Voss-Tecklenburg overcame Diacre strategically to lead her army to victory.

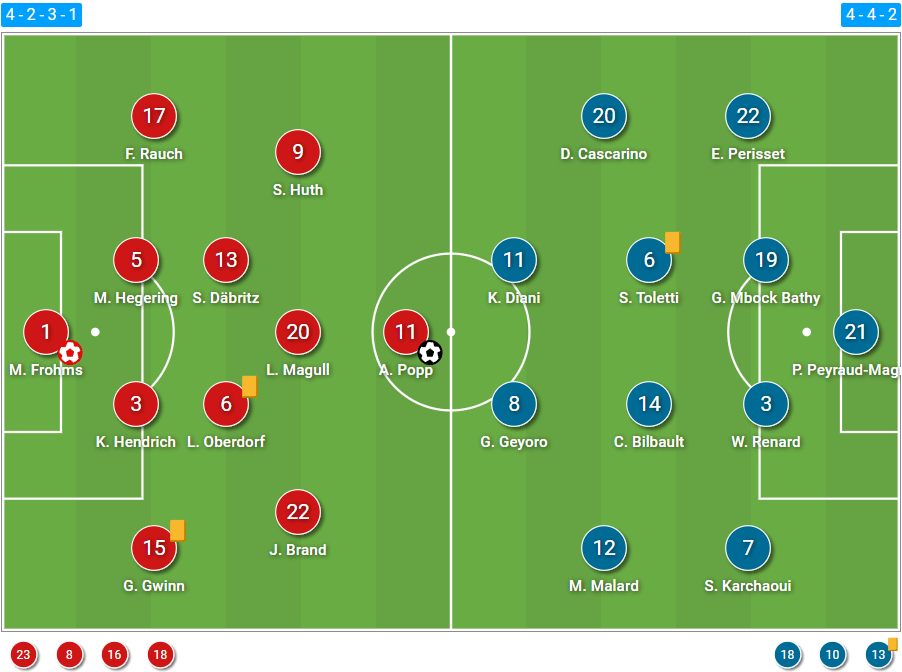

Lineups and formations

In anticipation of the lineups, many fans were wondering whether or not the two head coaches would make any changes from the sides that made it through from the quarter-finals.

Across both teams, there was merely one change, as Voss-Tecklenburg brought 19-year-old Bundesliga star Jule Brand into the starting eleven, deploying her off the left wing in place of Klara Bühl who missed a glaring opportunity towards the end of the previous game to seal their place in the semis. Of course, Die Nationalelf did manage to snag the victory in the end, but the manager may have been less forgiving.

The rest of the team remained exactly the same, but there was one question still on the lips of fans, particularly those with a keen analytical eye – would Voss-Tecklenburg employ the 4-3-3 or continue with the 4-2-3-1? The answer was the latter option.

For France, Diacre named an unchanged lineup in their usual 4-3-3 formation, although this converted to a 4-4-2 out of possession, but more on that later.

Pauline Peyraud-Magnin started between the sticks, protecting the goal behind a backline comprising of Ève Périsset, Griedge Mbock Bathy, Wendie Renard and Sakina Karchaoui.

Charlotte Bilbault sat at the nadir of the midfield trio, with Grace Geyoro and Sandie Toletti operating further ahead.

Finally, Kadidiatou Diani and Delphine Cascarino flanked the young Melvine Malard who led the line, although the attacking department was extremely fluid and constantly rotated during the game.

The two sides were filled with jaw-dropping quality as two tactical styles prepared to cross swords until one fell in defeat.

Germany’s central struggles and France’s compact block

While France did have a lot of the ball, their structure out of possession was more impressive. Starting in a 4-3-3 base formation, the French changed their shape in the defensive phases to prevent Germany from playing into Lena Oberdorf who operated as Voss-Tecklenburg’s deepest midfielder in possession.

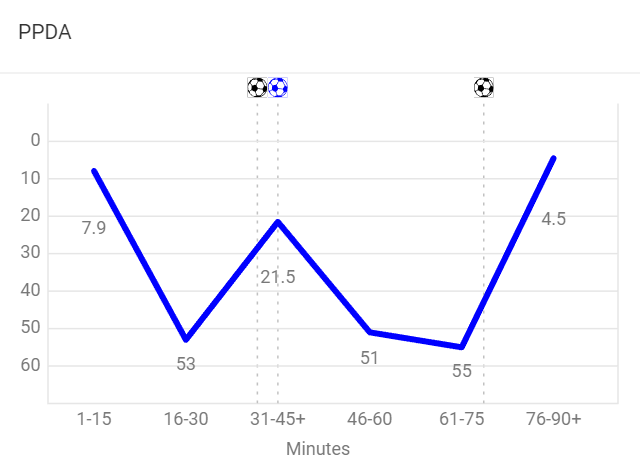

Firstly, one must note that France’s game-plan was not to press Germany high. At times, they did apply pressure when the Germans were building out from the back, but mostly, Diacre wanted her players to sit off and block central access.

Breaking the game down into fifteen minutes segments, France were not allowing Germany to have much time on the ball in the first and final quarters of an hour of the match. However, in between, Les Bleues were quite passive.

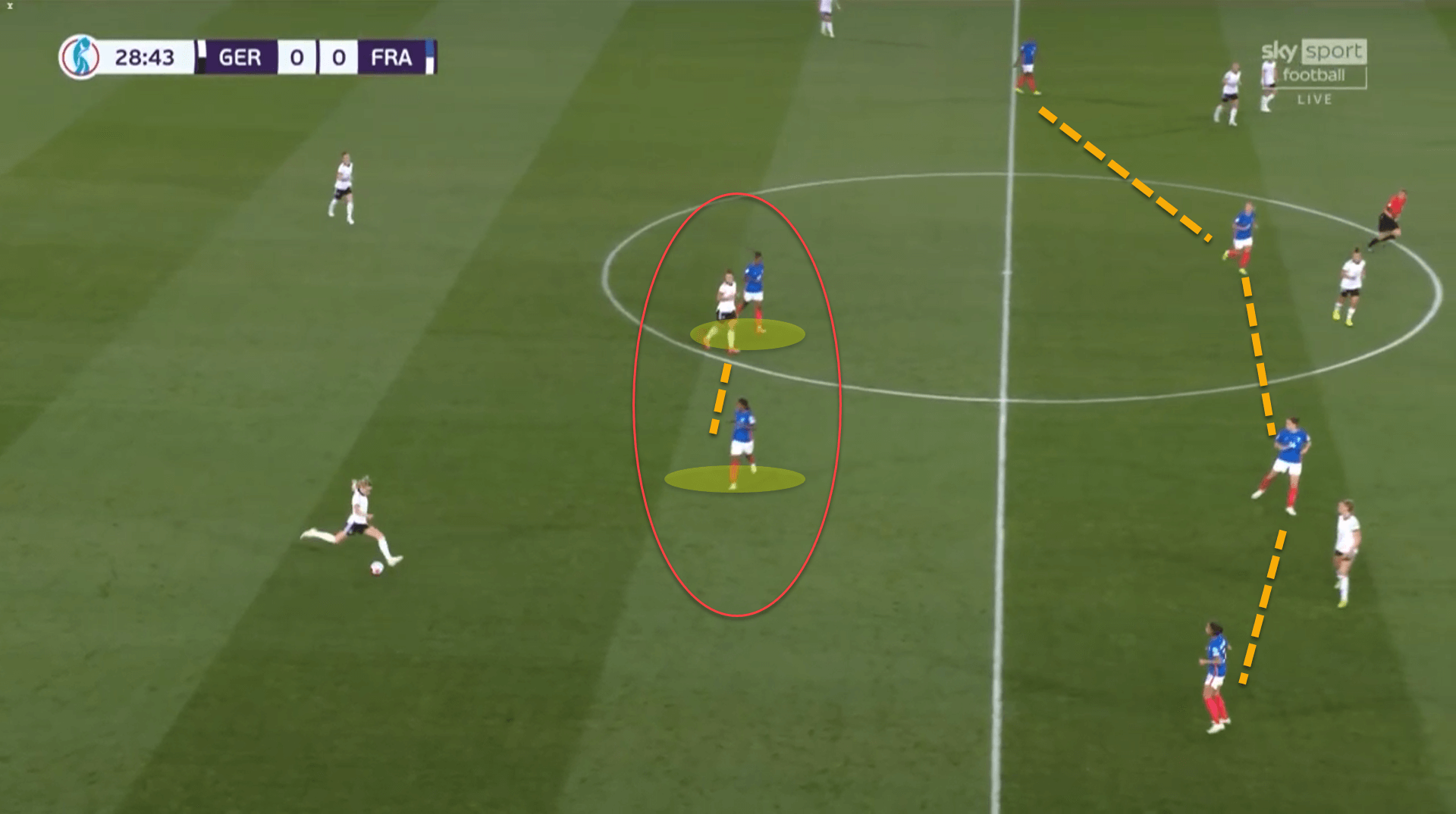

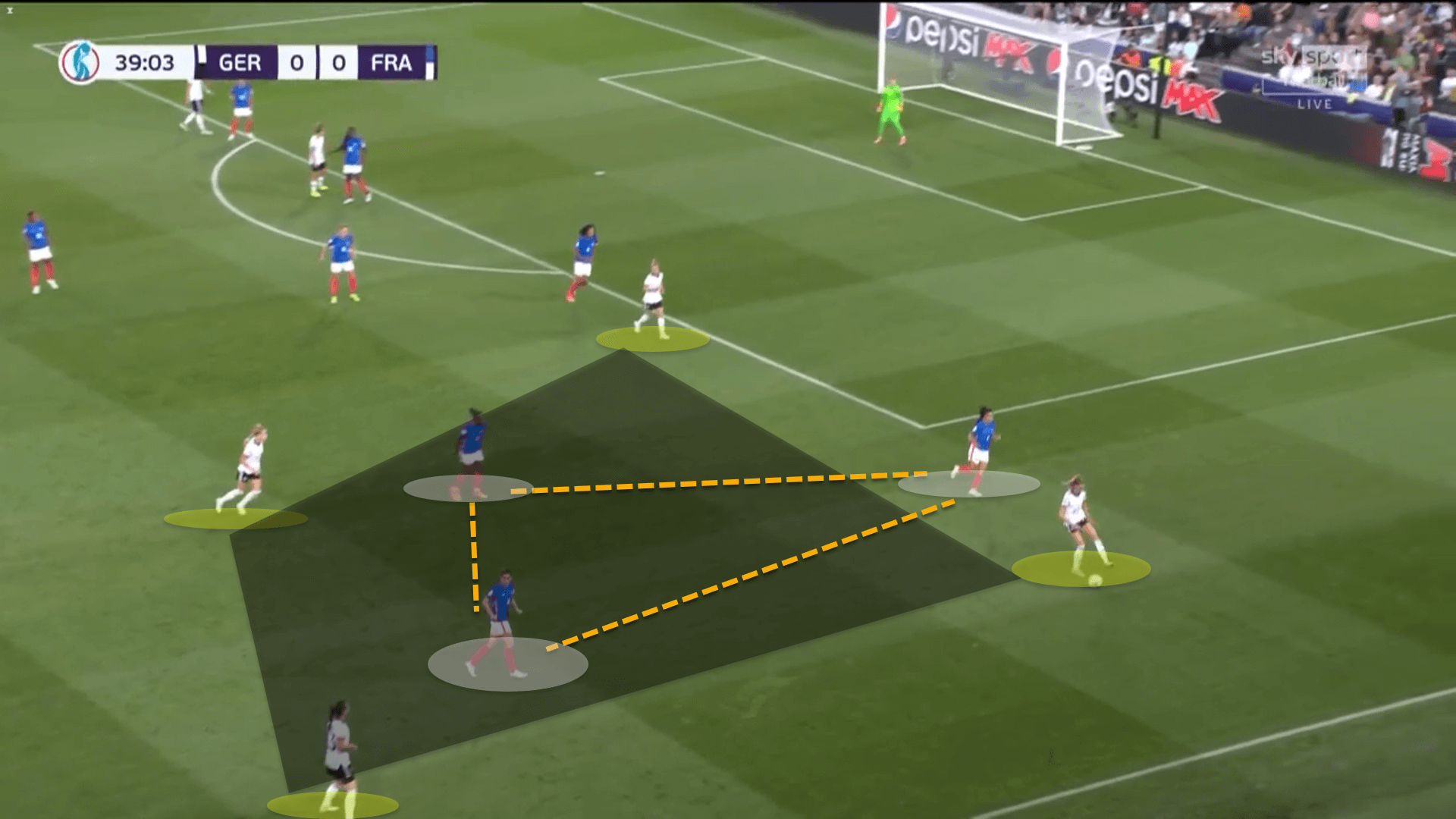

Despite playing as a central midfielder, Grace Geyoro would push higher to sit alongside the centre-forward when France were defending in a settled defensive structure, forming a two-person first line of pressure and creating a 4-4-2 shape out of possession. The centre-forward rotated quite a bit – sometimes it was Malard, other times it was Diani with Malard defending as a winger. Even Cascarino had a go at being part of the first line of pressure.

The pair were tasked with sitting on Oberdorf at all times. If one was pressing, the other would drop off and mark the German midfielder.

This was a smart plan by Diacre. Oberdorf was limited in her ability link the play between the backline and more advanced players which stifled Germany’s ability to progress the ball through the central areas.

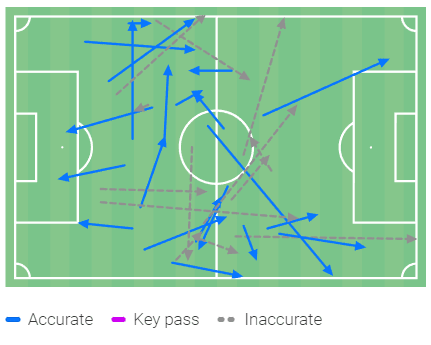

Overall, the 21-year-old completed just 21 of her 34 passes, an accuracy of merely 62 percent. Cutting off the ball supply to Oberdorf made Germany suffer in possession.

France’s defensive block was zonal. Essentially, what this means is that the players remained very close together, ensuring that the lines were compact both vertically and horizontally, keeping a close net around the players. As the old footballing saying goes, Diacre wanted such a tight-knit block that you could throw a blanket over all ten outfield players.

In this zonal approach, whenever Germany tried to play through the lines, France’s players would quickly crowd the ball-receiver to either win back possession or else force them outside the 4-4-2 defensive structure.

Since they couldn’t play their way through France by keeping the ball on the ground from the central spaces, Germany looked for different solutions.

The correct solution

Before observing how Germany eventually managed to grind France down to open the scoring at Stadium MK, it’s important to note what Die Nationalelf’s shape was in possession.

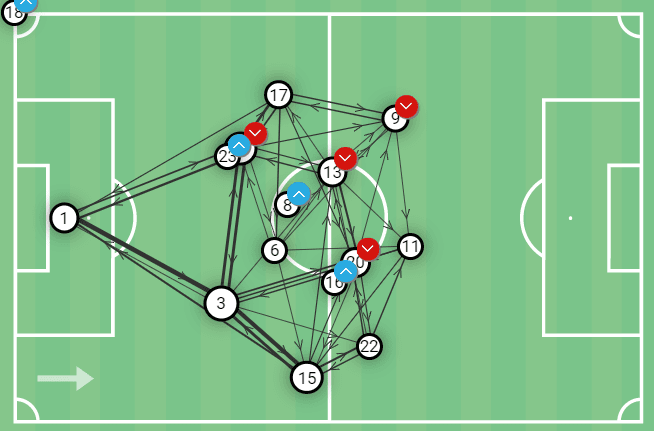

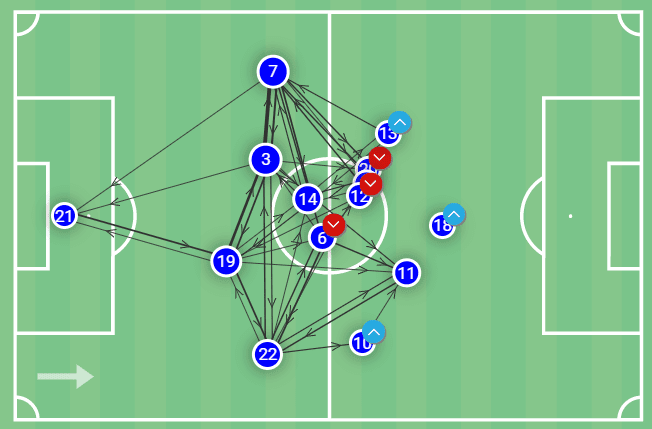

Despite using a 4-2-3-1 in the defensive phases, Germany’s structure in possession resembled more of a 4-3-3 with Sara Däbritz pushing up between the lines alongside Lina Magull, while Oberdorf operated as a lone pivot, as already discussed in the previous section. This shape is evident from Germany’s pass map for the semi-final.

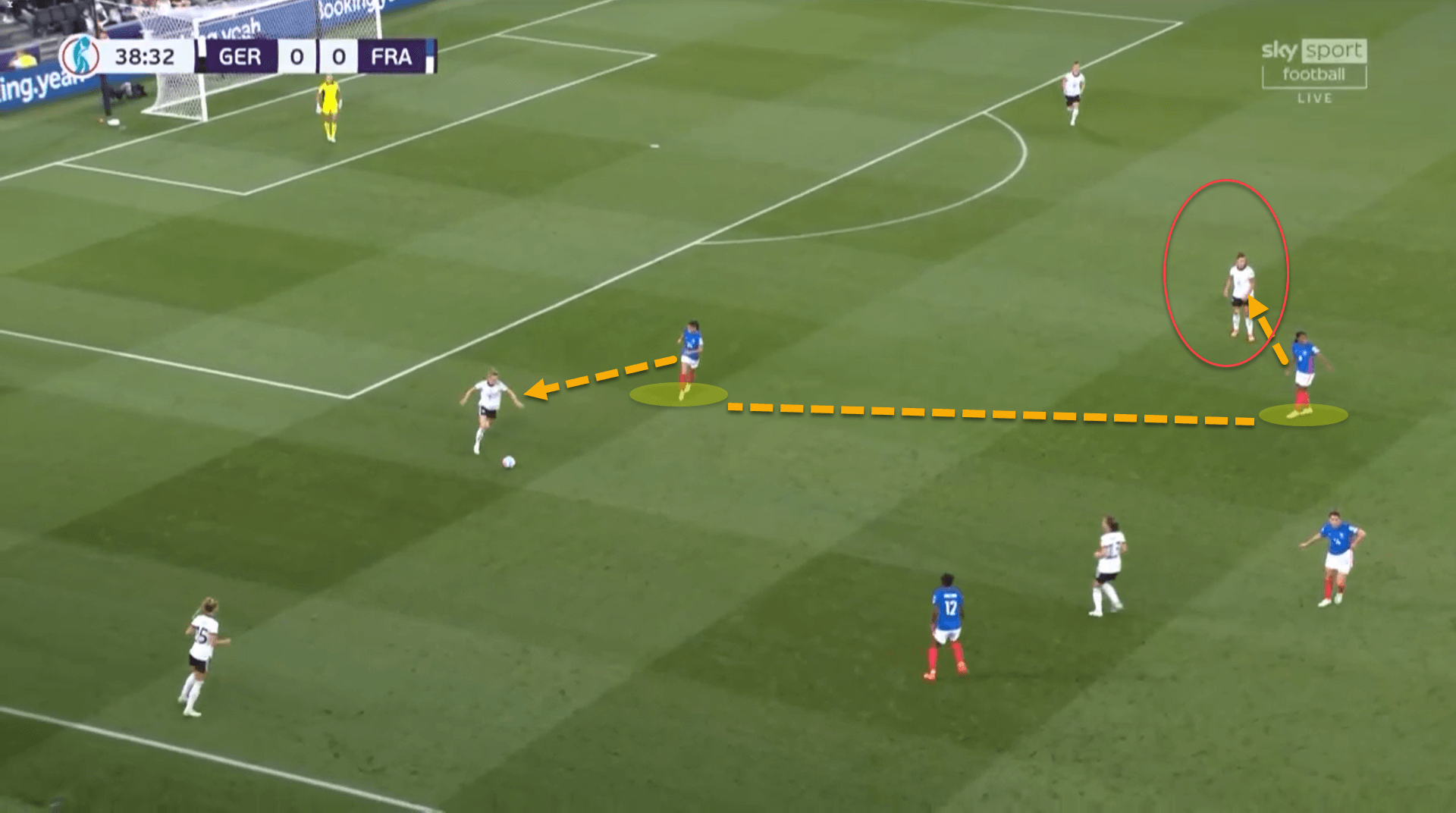

Germany had two solutions to France’s compactness between the lines. They couldn’t reach players in advanced positions of the opposition’s defensive block as the French midfield were doing a superb job at cutting off the passing lanes to these dangerous areas.

Voss-Tecklenburg and her players struggled for the opening half hour of the game to deal with this and often wasted possession. What was the solution? Well, in football, if you can’t play through a compact block, either go over it or around it. Germany did just this, displaying verticality in attack as well as flexibility.

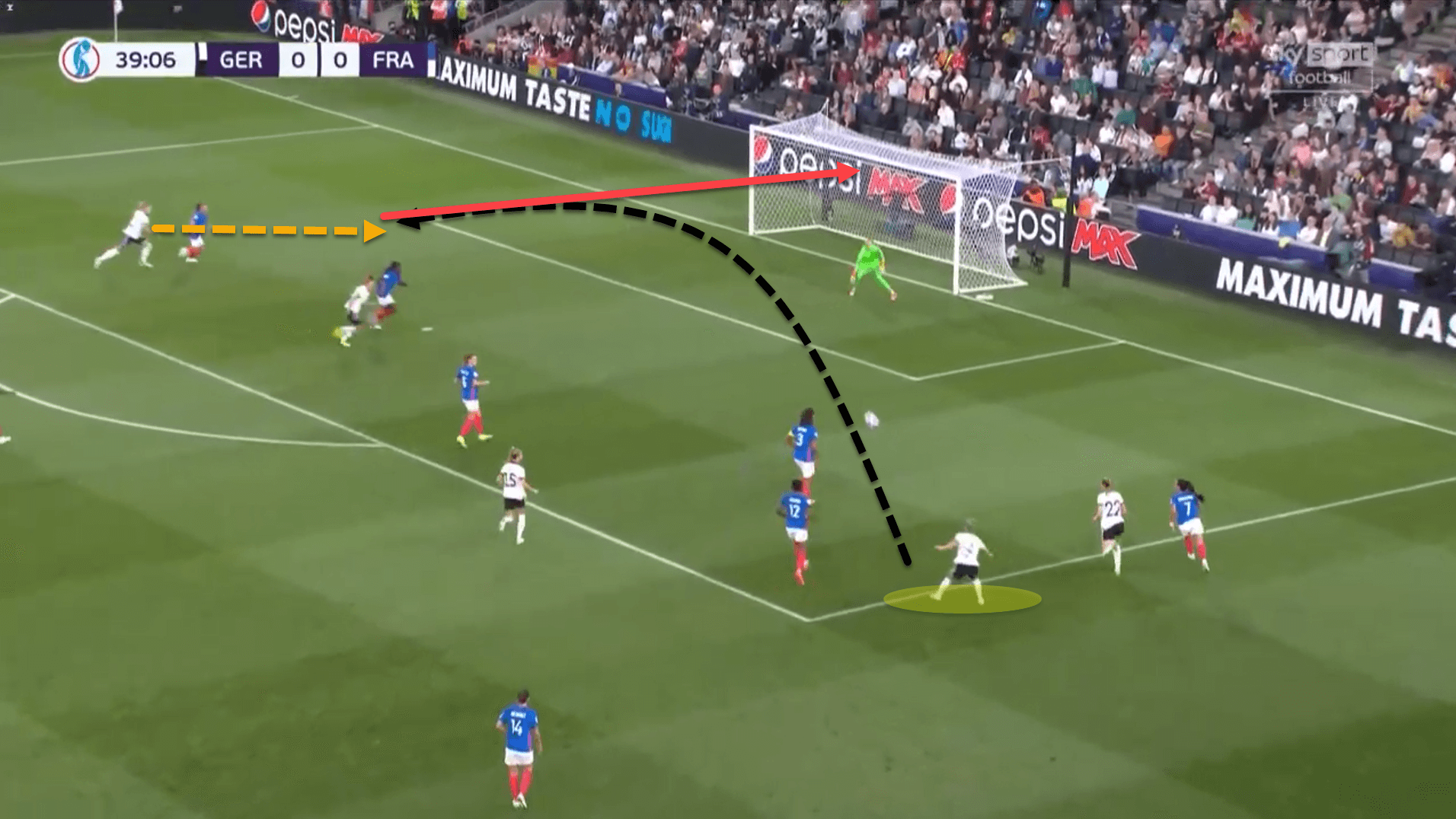

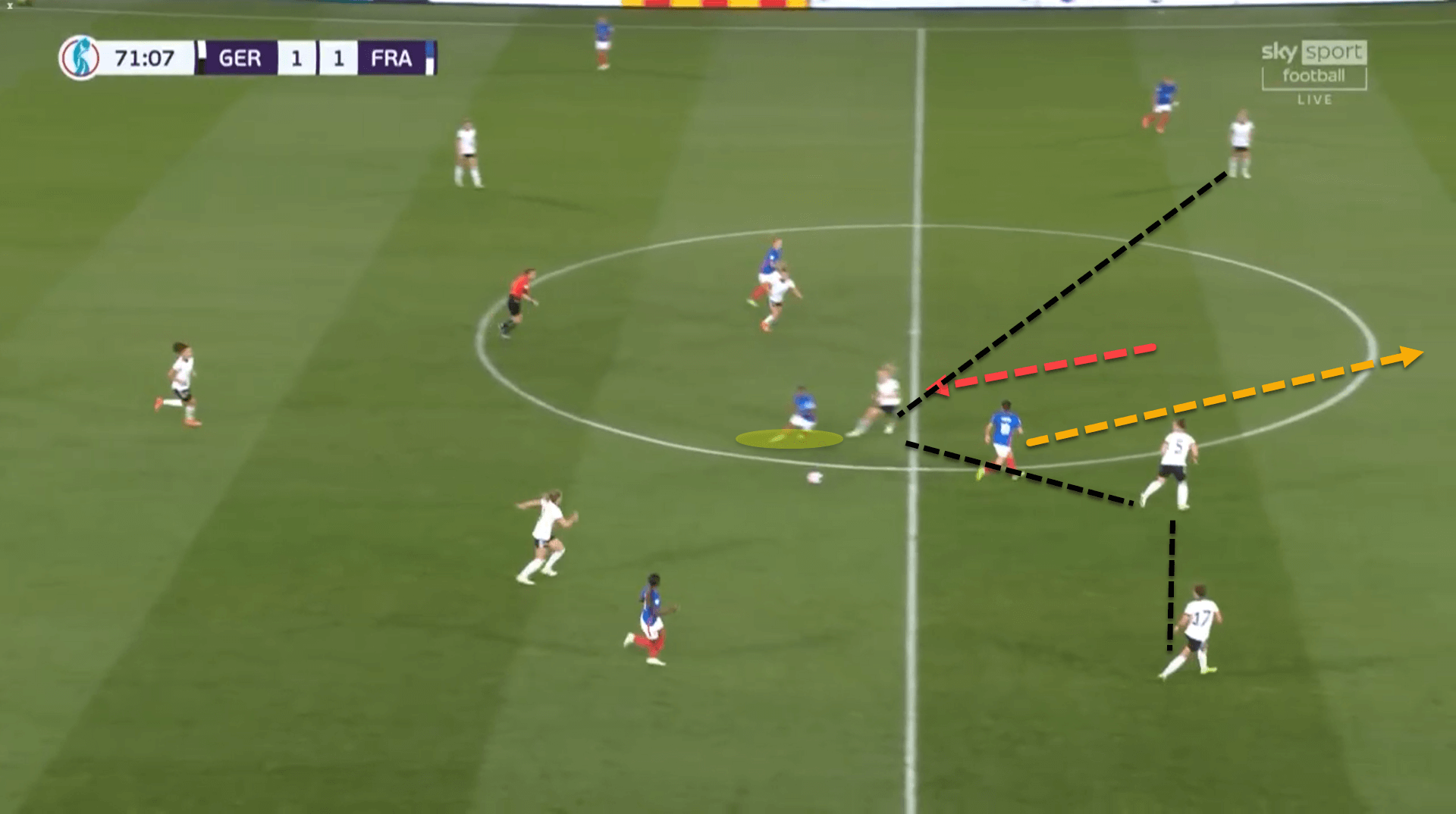

Both worked for Germany and led to their two goals. Firstly, Die Nationalelf began creating wide overloads, using numerical superiority to overcrowd the flanks, especially down the right.

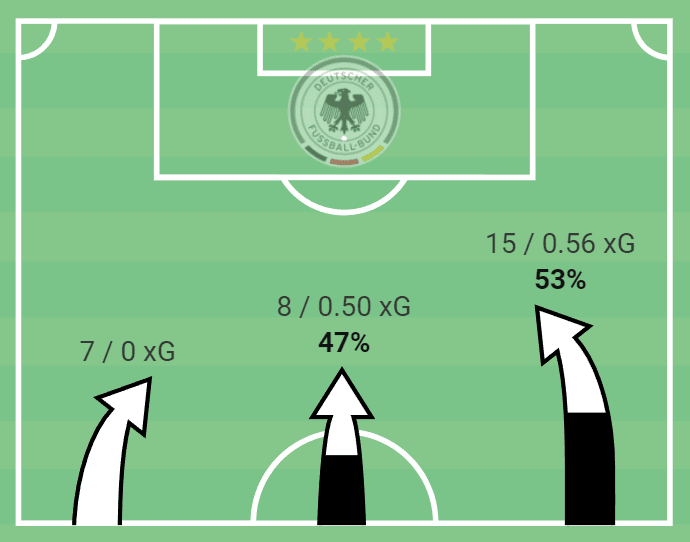

From Germany’s 30 positional attacks over the course of the ninety minutes plus stoppage time, 22 came down the wide areas, with exactly 50 percent occurring on the right side where players like Magull, Brand, Giulia Gwinn, Alexandra Popp or anyone else who drifted over were able to inflict significant damage.

It was a wide overload which led to the goal as Germany managed to outnumber France in a 4v3 situation. This allowed them to get a free player on the ball to cross into the box, which is one of the primary aims of a wide overload.

Svenja Huth was the free player. The two-time UEFA Champions League winner was found in space at the edge of the area unmarked. Huth floated the ball into the back-post where Popp latched on and stroked the ball high into the net to open the scoring.

Later in the game, as the score was stuck at a deadlock, Germany‘s next solution worked wonders to help them take the lead again. After receiving the ball in a minute bit of space, France failed to close down Sydney Lohmann before the Bayern Munich Frauen midfielder hit a sumptuous switch of play out to Huth once more.

As the play developed further, Huth flung the ball into the box once more and Popp headed home the winner to put Germany’s second foot into the final at Wembley.

Sometimes you won’t always be able to play through an opponent and so teams need to be adaptable with their attacking approach. This flexibility in the offensive phases was why the Germans edged France on Wednesday.

Safety first

Not only did Germany’s attacking pliability help them be victorious in Milton Keynes in midweek, but France were the masters of their own downfall.

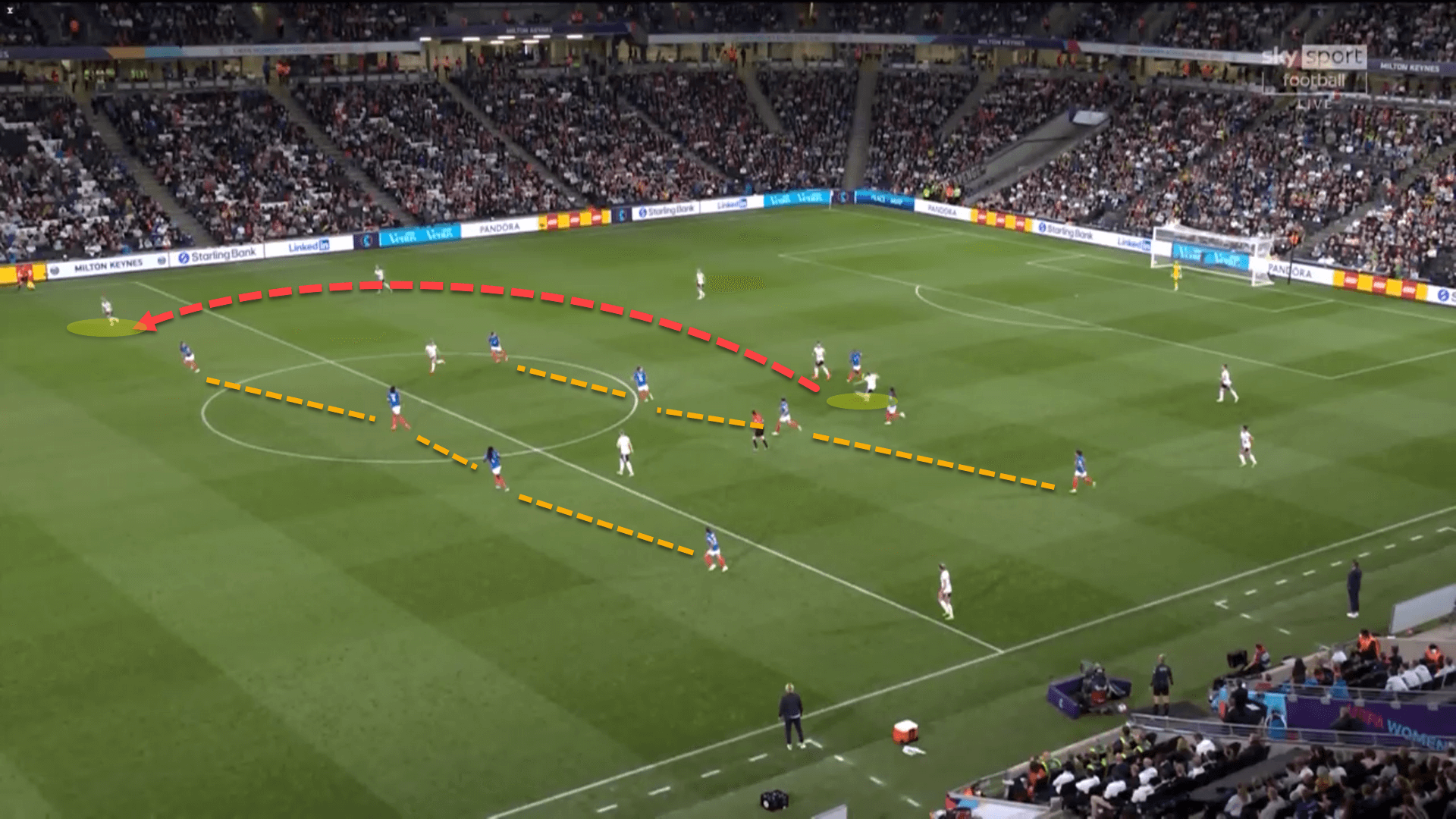

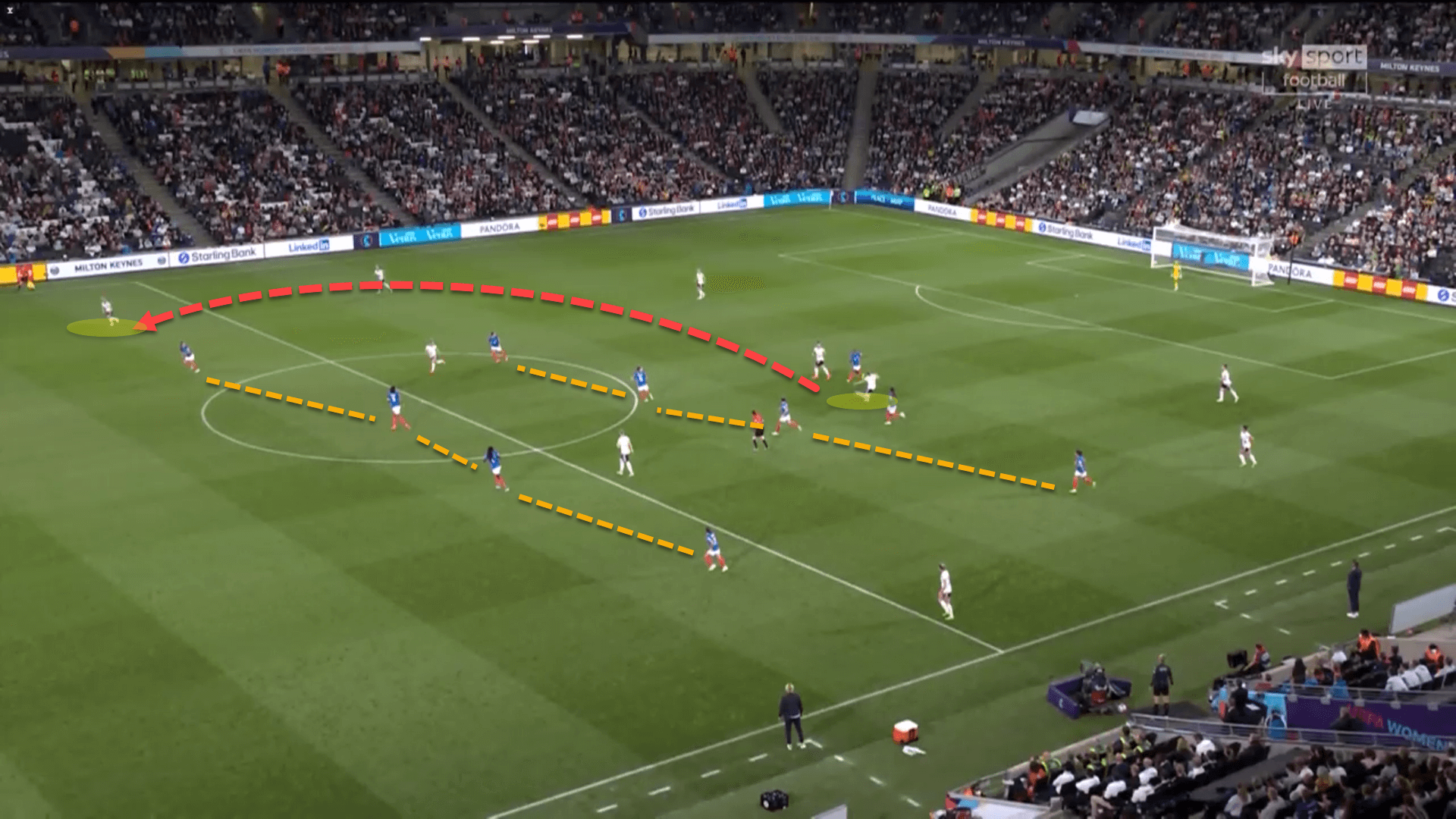

One of the most admirable aspects of how Voss-Tecklenburg’s side plays is their bravery out of possession. Usually, when an opposition player receives the ball between the lines and turns, facing forward, the defensive line will drop. This is to try and limit the space the player has to play into behind the backline. However, Germany don’t abide by this methodology.

Here, the French player is bearing down on the backline. Instead of instantly dropping to smother the space between themselves and the goalkeeper, the defensive four hold the line for as long as possible, keeping their close distance from the midfield.

Of course, the biggest downside to this is that, should a team play in behind them, the backline can be caught out, especially when the runners possess rapid speed.

This was something that Diacre was aware of, and France did try to attack the depth on several occasions throughout the match. Unfortunately, their final ball really let them down. Over the course of the game, 13.03 percent of France’s passes were long balls. Only 52 percent were accurate.

Furthermore, Les Bleues lacked quality overall when trying to carve Germany open. From 7 smart passes against the Germans, France didn’t even complete one. Wyscout defines a smart pass as “a creative and penetrative pass that attempts to break the opposition’s defensive lines to gain a significant advantage in attack.”

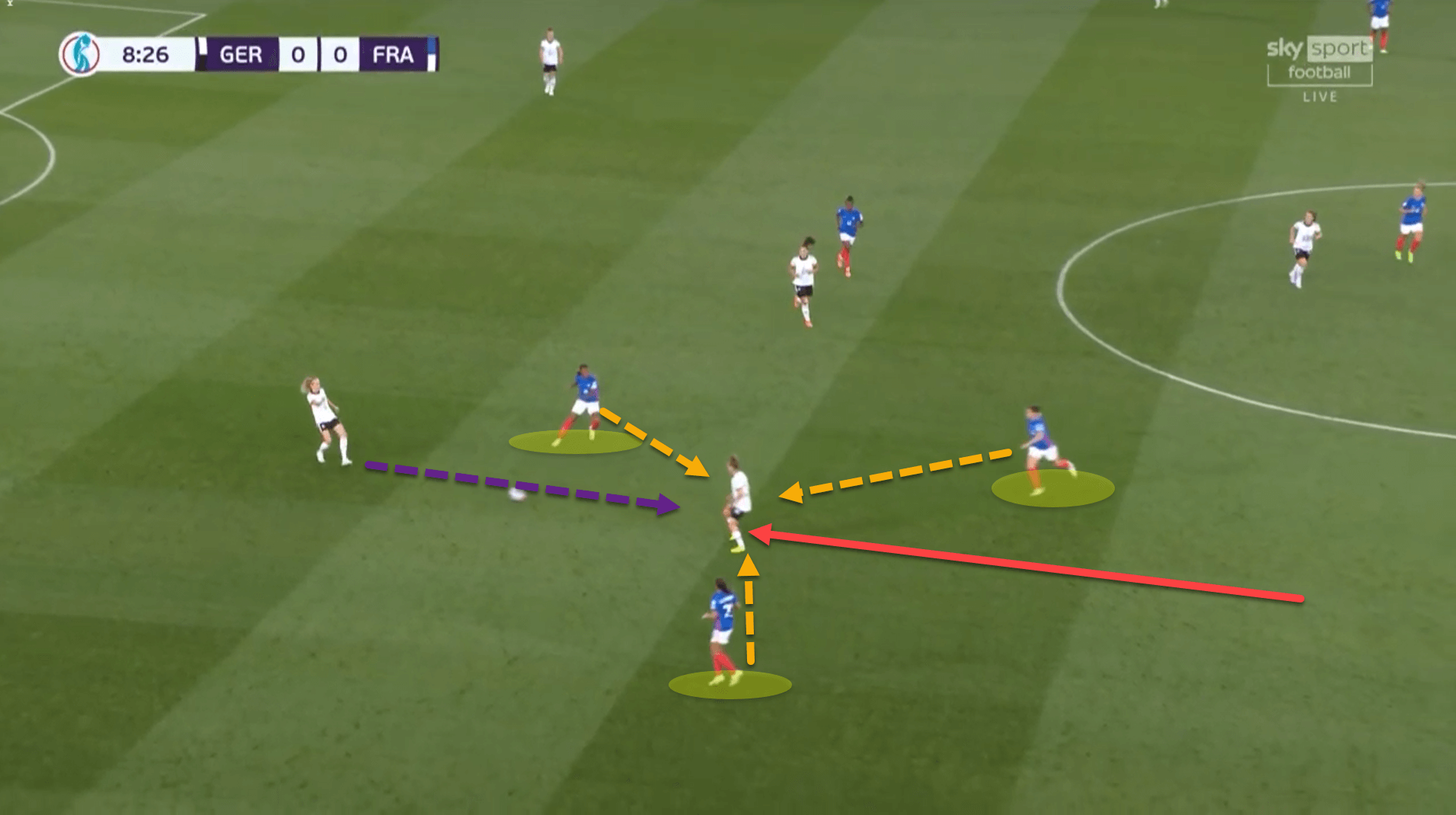

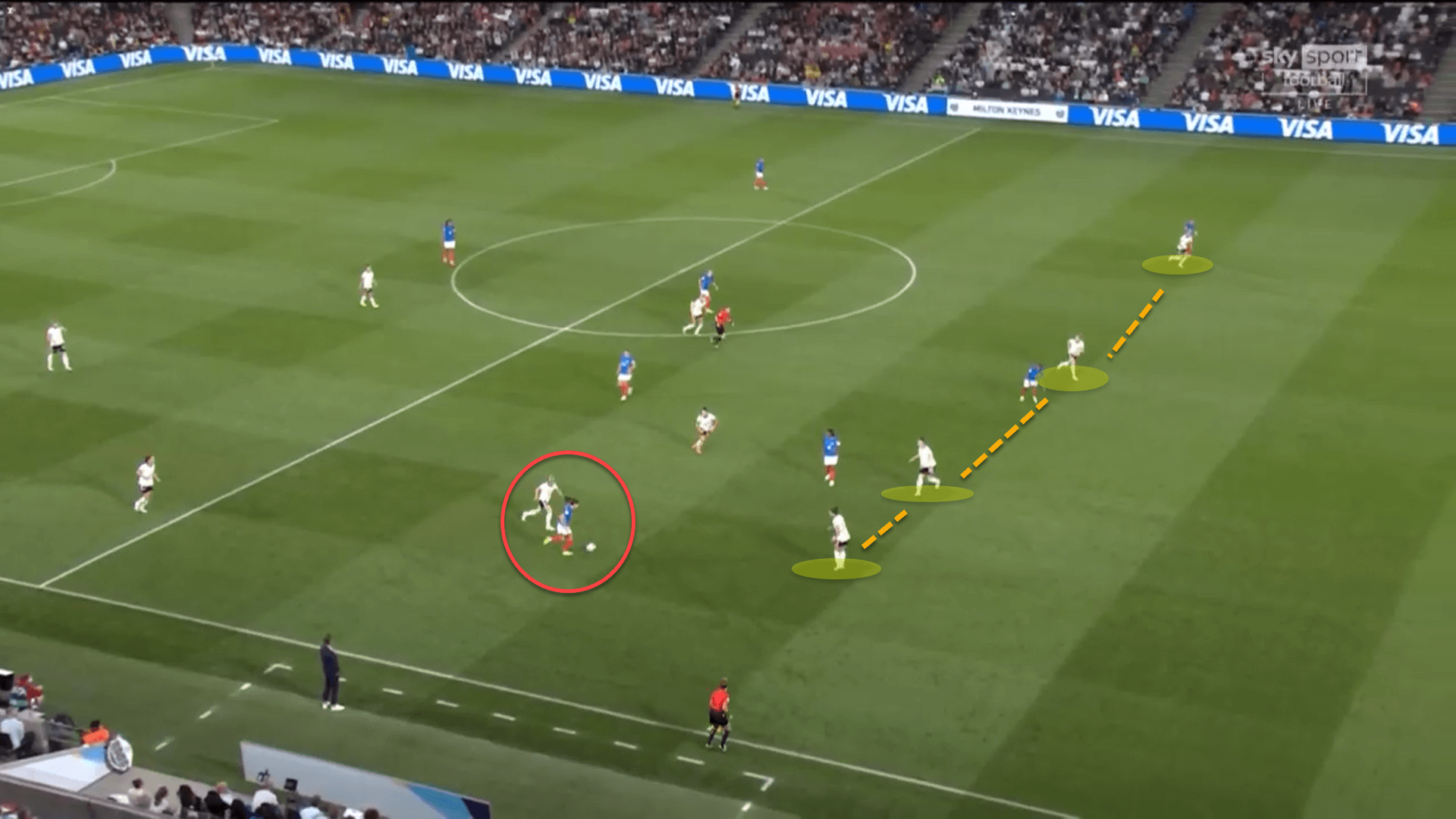

Here, for example, the French forward dropped slightly deeper when receiving, dragging the German central defender out of the backline, leaving a huge gap in the defence.

Diacre’s side failed to take advantage of such a vast, exploitative hole, one of the many times this happened throughout the night.

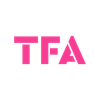

Moreover, when France were attacking in a settled positional structure, the manager held the fullbacks deeper, possibly out of fear of Germany’s efficiency on the counterattack.

As shown from France’s pass map, centre-back Renard had a similar level of depth as the two fullbacks. This is quite rare to see in the modern game and even more confusing considering the gravity of the tie.

Les Bleues had little width throughout the match since the fullbacks didn’t really have license to get forward, meaning the forwards were predominantly isolated against Germany’s backline.

While one must respect Diacre’s reasoning, it’s difficult not to question her motives. Arguably, advancing the fullbacks higher would have elevated France’s attack. Overall, the French ended the game with an xG of just 0.53 from 14 shots. Going forward, Les Bleues were feeble, to say the least.

Conclusion

The stage is now set. Voss-Tecklenburg’s Germany will take on Sarina Wiegman’s England at Wembley Stadium this Sunday.

It’s almost too perfect for the Lionesses not to lift the trophy by the end of the night, but football is a cruel sport and finds the most inventive ways to upset the apple cart. Germany will not lay down and roll over for the English, nor would anyone expect them to.

A true spectacle of wonderful, attacking football will be on display, with buckets of quality on the pitch and on the touchline. For fans of both sides, it will be a nervy affair, but for neutrals, it’s time to kick back, relax, and enjoy ninety minutes of sporting bliss.

Comments