“Welcome to Wrexham” swept the globe.

The social media darlings, owned by Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney, captured the hearts of football fans everywhere. Even the casuals and previously football-disinterested took an interest in the fifth-division Welsh club and it followed its story.

After a disappointing first season under the new owners, a record-smashing second campaign has us saying, “Welcome to League Two.”

From late-season drama against Notts County and a palpitating title race that took 45 weeks for a decision, it was a Hollywood ending for the world’s favourite small club.

In this tactical analysis, we’ll break down some of Phil Parkinson’s tactics leading to their success. This scout report will look at both sides of the ball, especially at how their ball-near overloads helped them create a cohesive tactical system that carried them to promotion. The league is won and promotion is secured, so this analysis won’t stop at the club’s 2022/23 tactics. Let’s move beyond the past season and look to the future. Using data to contextualize performance metrics across England’s top five divisions, we will relate Wrexham’s season averages to those across the first five tiers in the English football pyramid.

Settle in for the tactical story and a glimpse of the Red Dragons’ future.

Attacking overloads and getting behind the lines

Wrexham and Notts County were neck and neck in nearly every respect this season. From the title race to the bragging rights for most goals scored and fewest conceded, it was a fight to the end. A cohesive game model that accentuated the top qualities of leading players was the key to Wrexham’s success.

When you talk about their attacking output, it’s inherently tied to the way they attacked the wings in their 3-5-2. Whether looking to get in behind or overload the opponent in the wings to create conditions to switch play, Wrexham’s emphasis on the wings was undeniable. Generating numerical superiorities in the wings created imbalances in key parts of the pitch, which the Red Dragons were quick to attack.

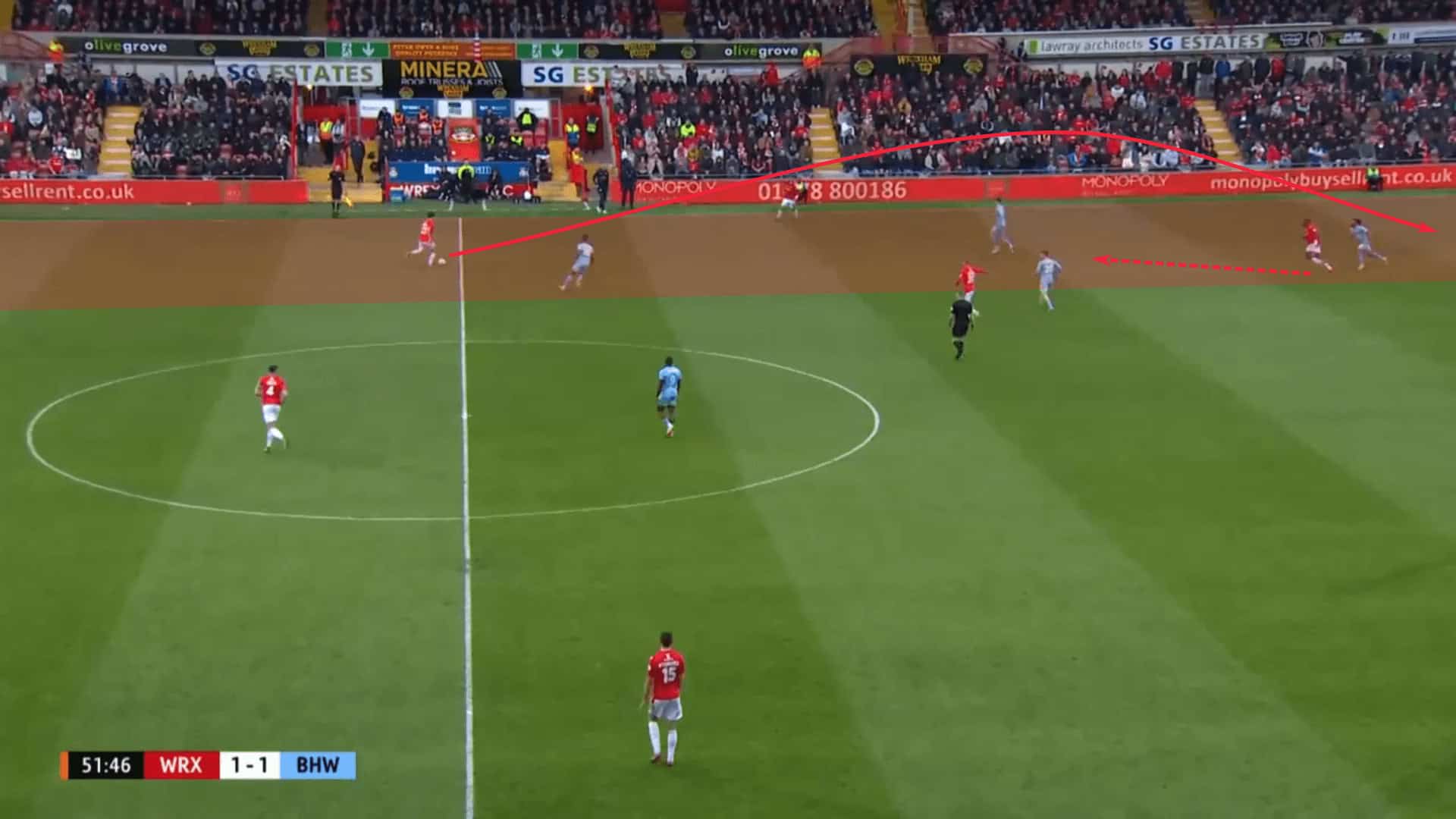

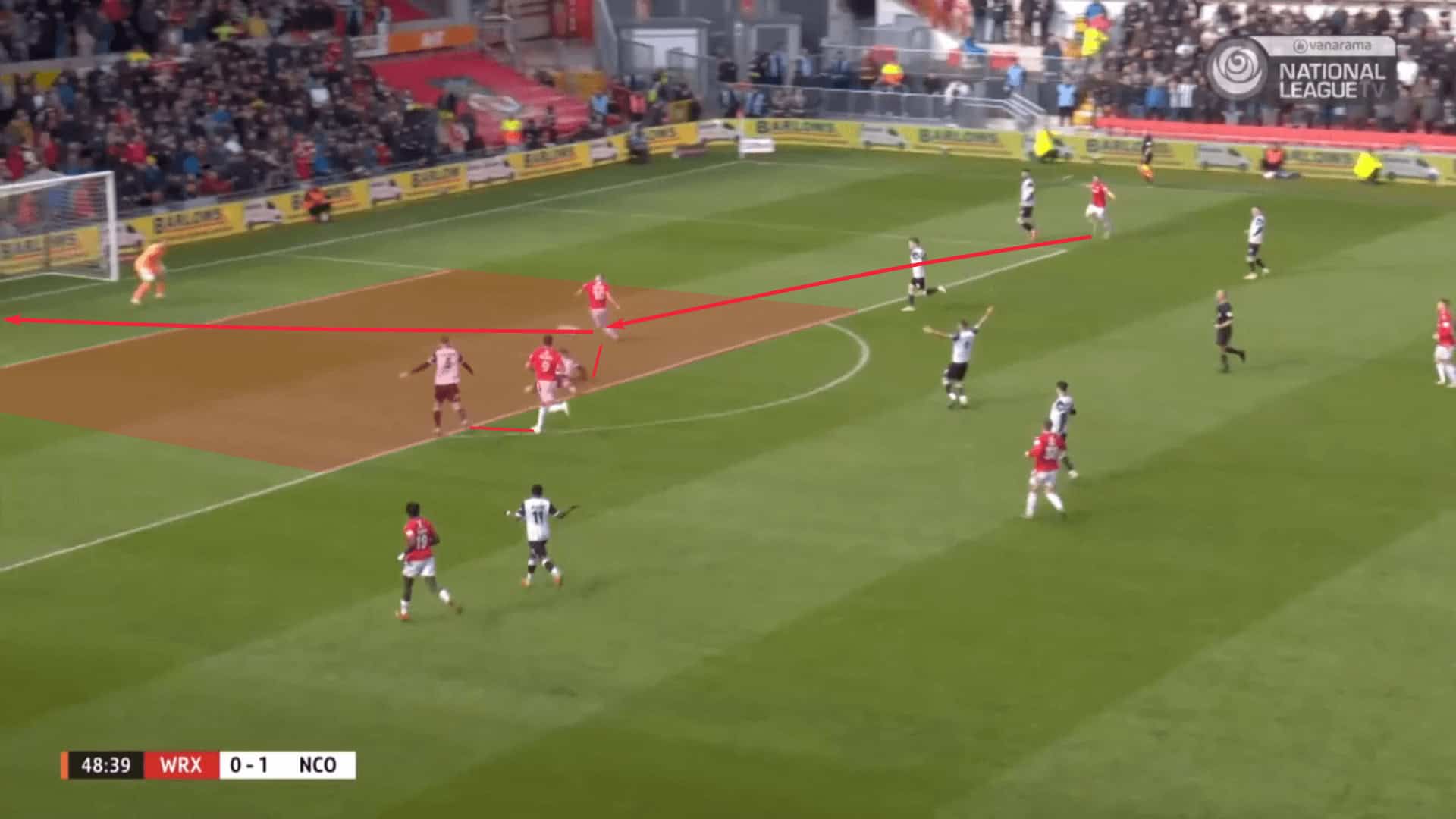

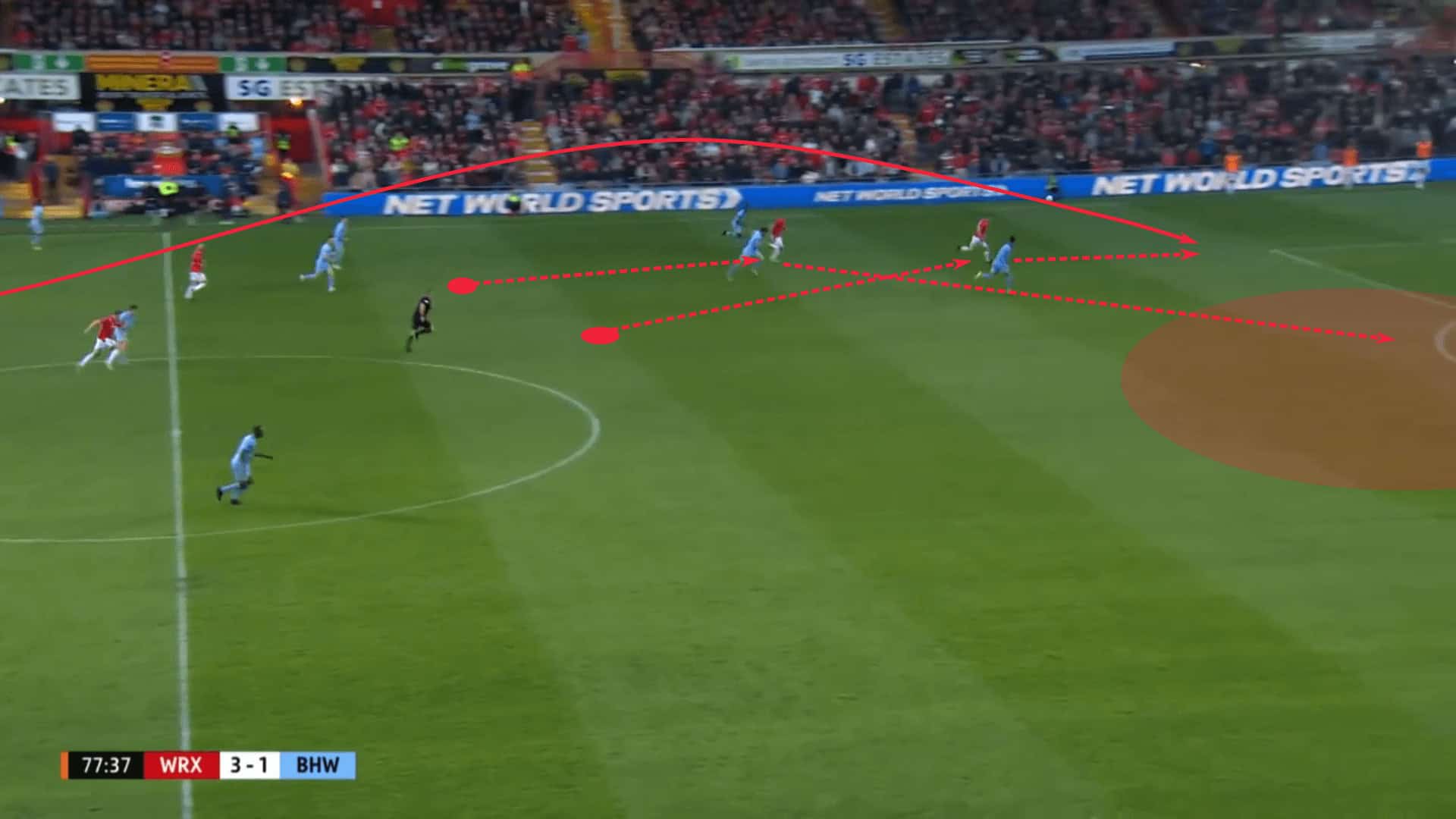

Take this wide overload against Boreham Wood. Four players are in the right wing while the central player of the midfield five, Andy Cannon, the former Championship player with Hull City, took his position in the right half-space. You can see his arm extended as a field general determining the next sequence of action. As Wrexham overloaded near the ball, look at the numbers in direct opposition to the Boreham Wood backline. Wrexham has established a high 4v4. They’re simply looking for the right moment to attack it.

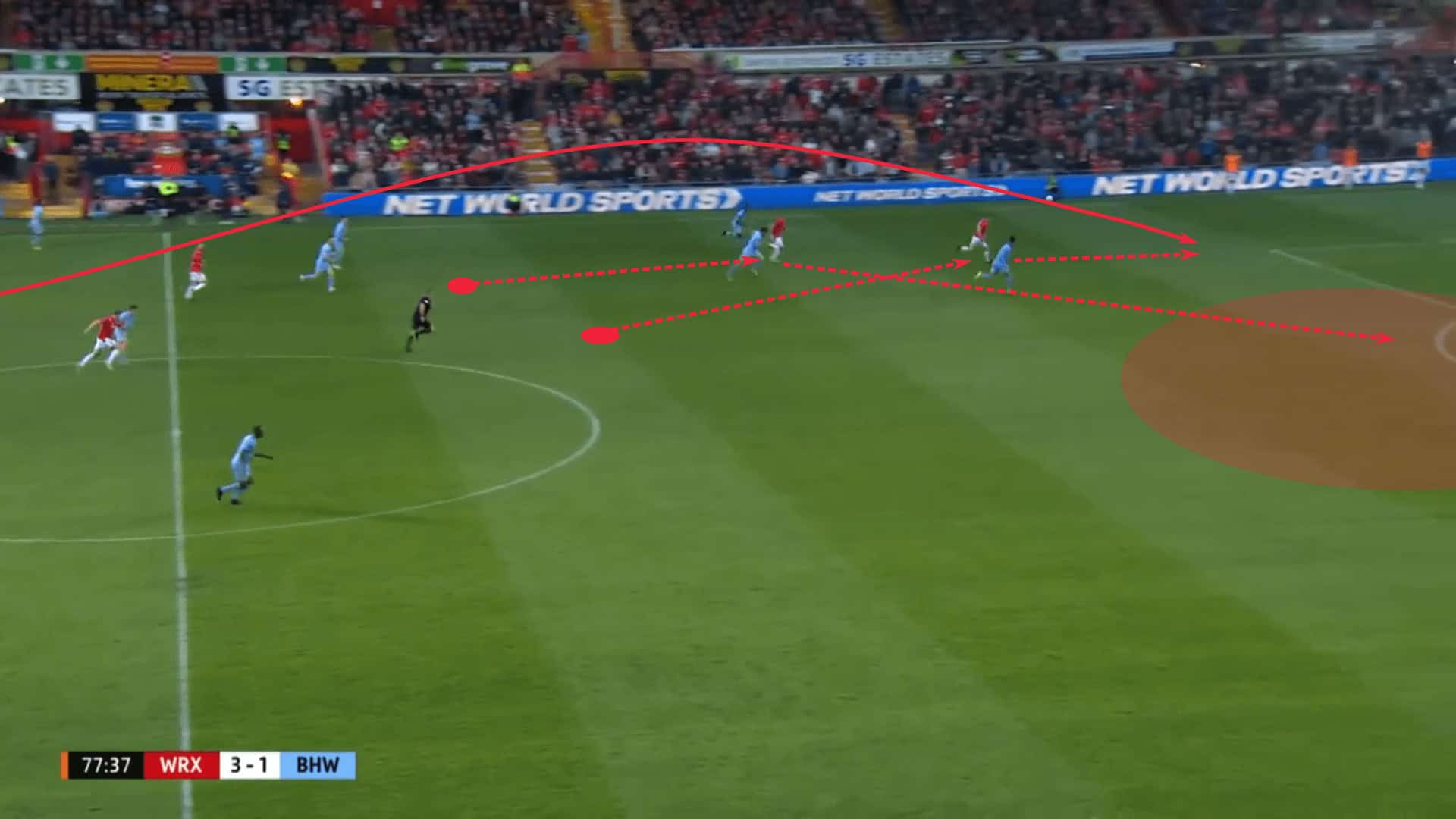

After the switch of play, which Cannon directed, Wrexham held the ball in the left wing to develop the attack. Notice again that three players are in the left wing and Cannon is again in the half-space, this time on the left side of the pitch. He gives them that central balance in case of a turnover. As Jacob Mendy, the left midfielder, checks from his high position, his movement creates a gap between the Boreham Wood right-back and right-centreback. The ball goes over the top and is collected in the wing by Paul Mullin. He beat his defender to the inside and unleashed a beautiful curling shot for the league-winning goal.

One of the benefits of Wrexham’s ball-near overloads and the central presence of Cannon is that they are well-positioned for defensive transitions. They can easily delay the opposition’s attack and get numbers behind the ball. That’s exactly what we saw against Sheffield United in their FA Cup game. The central numbers have taken away the most direct path to goal and slowed the Sheffield United counterattack. It’s that cohesion from one phase to the next that Wrexham was targeting. They attacked with a thought of defending and defended with a thought of attacking.

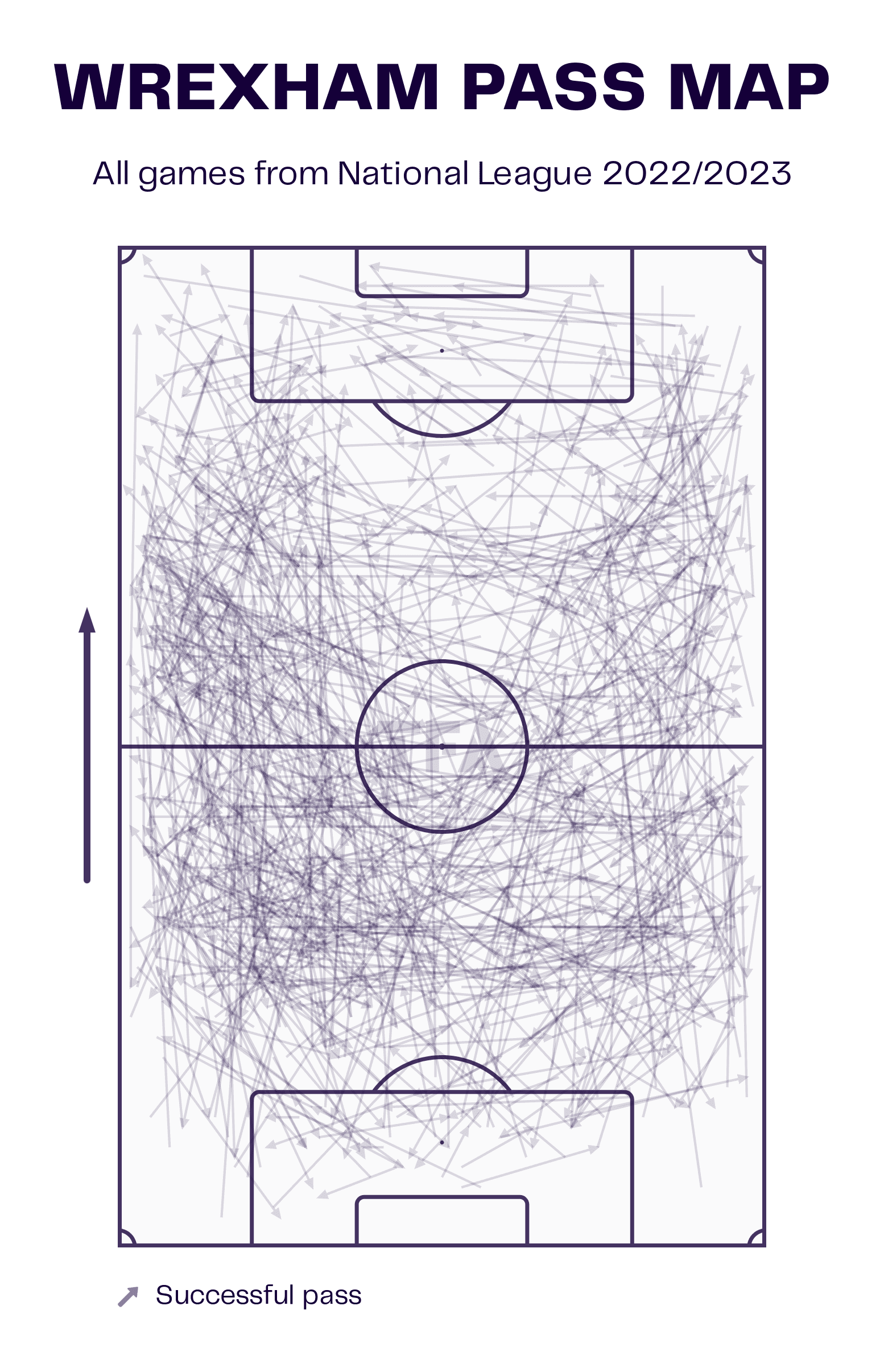

To mitigate the opposition’s threat, especially on the counterattack, we see how their 3-5-2 was implemented. The pass map lights up in the wings and is fainter centrally, especially in the opposition’s half of the pitch. With a 50/50 split in average possession for the season, this was not a Wrexham team that spent large swaths of time camped in the opposition’s half of the pitch. High-tempo attacking was the preferred approach. Once they could find that ball in behind, especially through the wings, they were off.

The use of two forwards was a constant problem for the opposition. In the 3-5-2, the two wingers would push high up the pitch to engage the opposition’s outside backs, creating a 4v4 against the opposition’s backline. That allowed the two forwards, typically Ollie Palmer and Mullin, to engage the centre-backs in a 2v2.

A common theme was for the nearer of the two forwards to push into the wider regions of the half-space and drop slightly lower than the second forward. It was the higher forward that Wrexham targeted as they looked to get behind the backline. With him pushing the far-sided centre-back into the near-sided half-space, the middle of the pitch was often vacant. As that space opened up, the other forward would burst into it from his deeper position. Effectively, it was a foot race between him and the other centre-back to get into that space. Even the slightest mental lapse from the opposition was enough for Wrexham to get into a dangerous scoring position.

If both forwards remained more central or there was a quick switch of play that didn’t allow them to get across the pitch, the midfielders would look to make those runs behind the line as well. So long as the opposition’s backline was 4v4 against Wrexham’s wingers and two forwards, there was always space to attack as the right winger, Ryan Barnett, dropped deeper to support possession.

As the Red Dragons made their quick move into the final third, the remaining high players knew their job was to provide targets in the box. That’s exactly how they scored one of their pivotal goals of the season, the equalizer against Notts County. As James Jones sprinted into the wing, the forwards found themselves 2v2 centrally. As they jockeyed for position, it was Mullin who outmuscled his opponent to arrive in the box and apply the first-touch finish.

Again, this was not a side that looked to keep the ball for its own sake or unbalance opponents with intricate combination play. Overloads in the defensive and middle thirds were designed to create more direct possessions, one of the topics of a former tactical analysis. When they entered the attacking third, they looked for quick moves to get to goal. That approach was lethal this season, leading to 116 goals on 87.53 xG.

Compact shape and numbers behind the ball

Only Boreham Wood’s 40 goals conceded and the 42 allowed by Notts County bettered Wrexham’s. The Welsh side gave up 43 goals on a league-leading 38.65 xGA. A tight defence was key to their season’s success.

As seen in the last section, when Wrexham lost the ball, they typically had numbers nearby to quickly counterpress or get behind the ball centrally. Their defensive transitions were superb.

Out of possession, the two wingers often dropped in to make a backline of five with three midfielders in front of them and the forwards either side by side or high and low. In the high press, they were typically side by side to limit the opposition’s centre-backs. As the opposition pushed into the Wrexham half of the pitch, one of the two forwards often dropped deeper, typically to the same depth as the opposition’s #6.

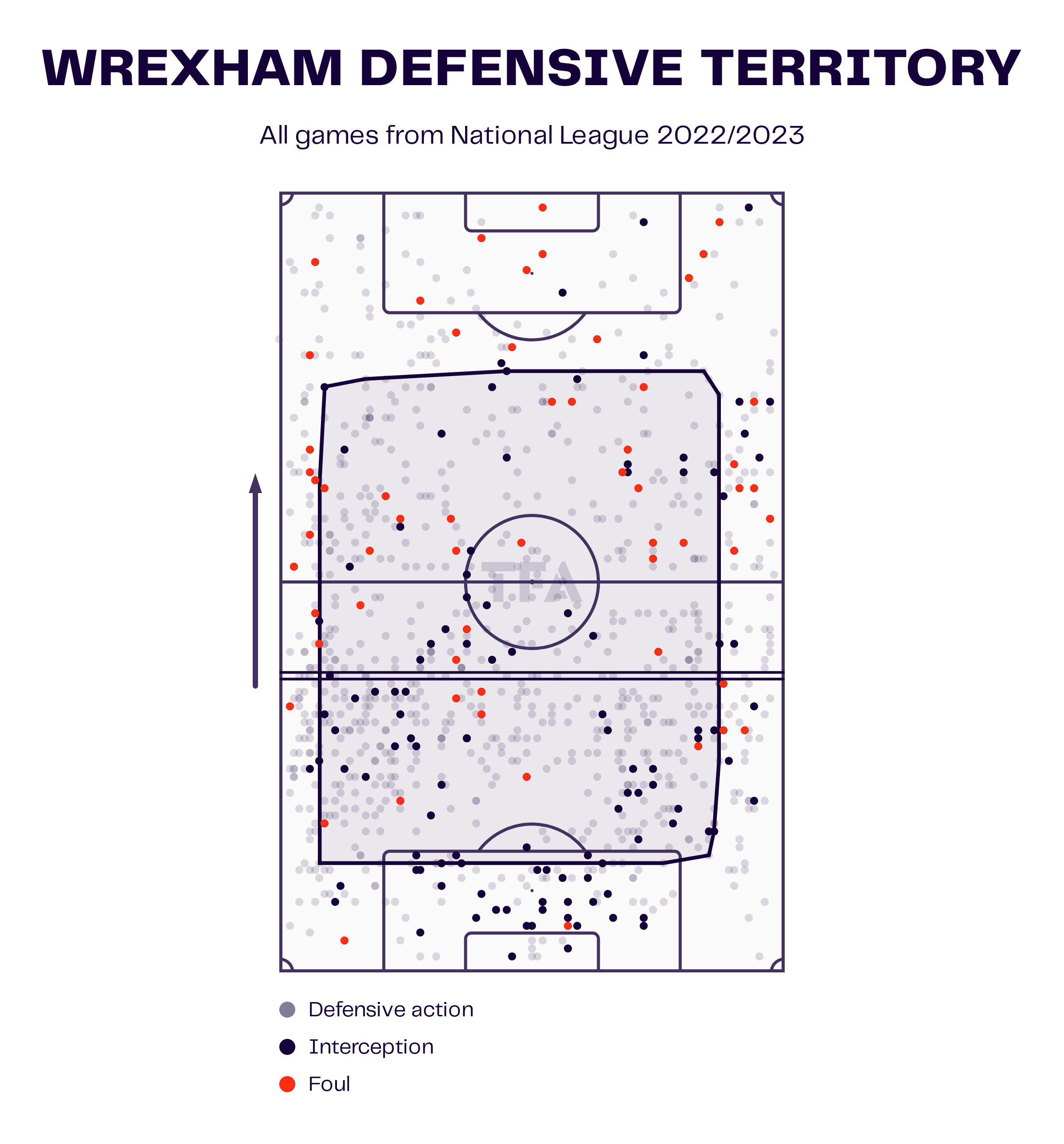

Looking at their average defensive territory, you do get the sense that this was a team that was very comfortable in the high press. Their 14.31 high recoveries, a very respectable total, were a good indication of their success defending in the opposition’s half.

The average recovery line is very high too. This signals a nice blend of high and middle recoveries to balance out the inevitable low recoveries.

Another point worth mentioning is the location of the defensive actions. Notice that they are sparse in the central channel. Even the interior areas of the half spaces have limited actions. Overall, they did very well to limit the opponent’s success through the middle, forcing them into the wings before ramping up their pressing intensity.

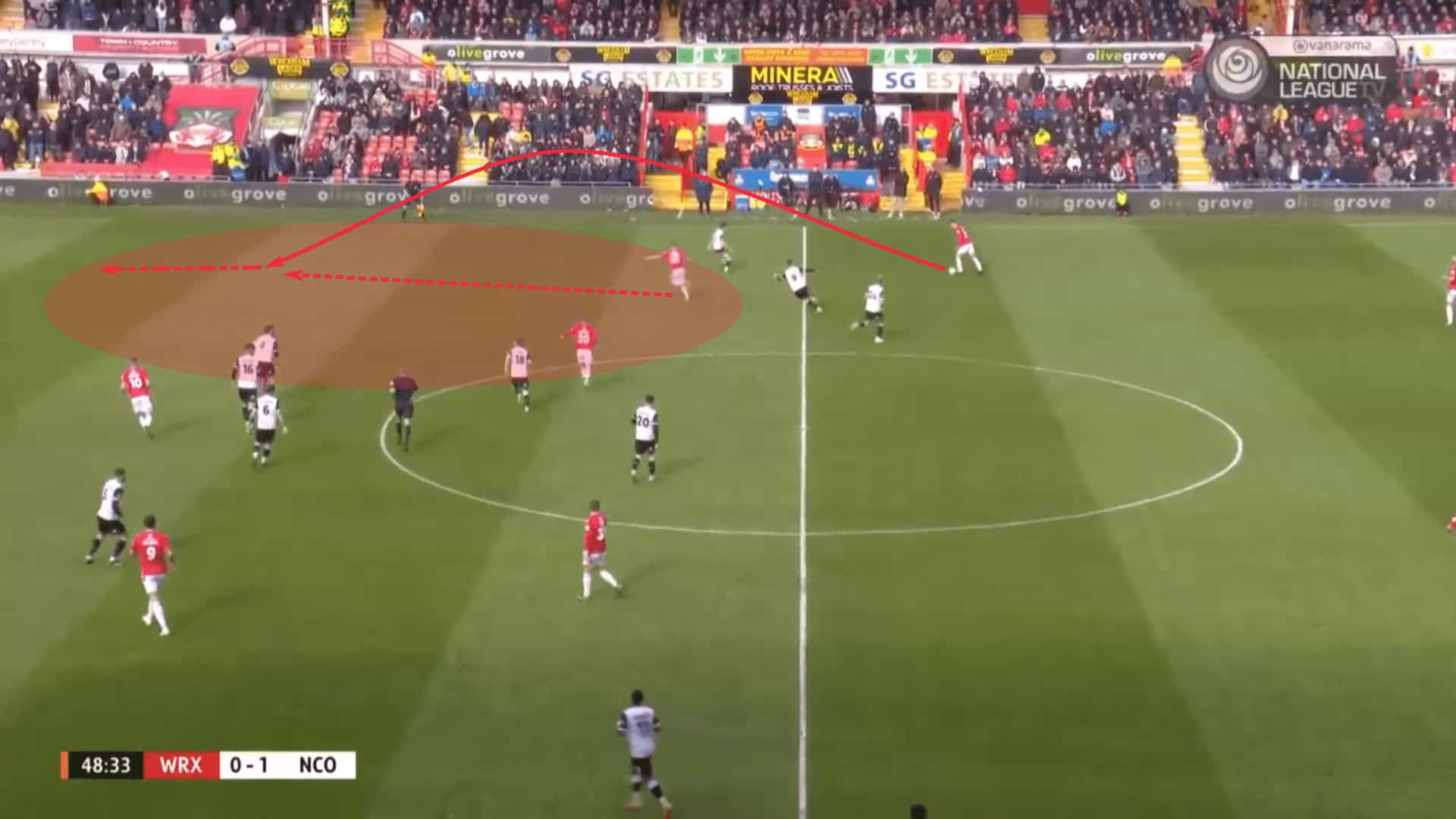

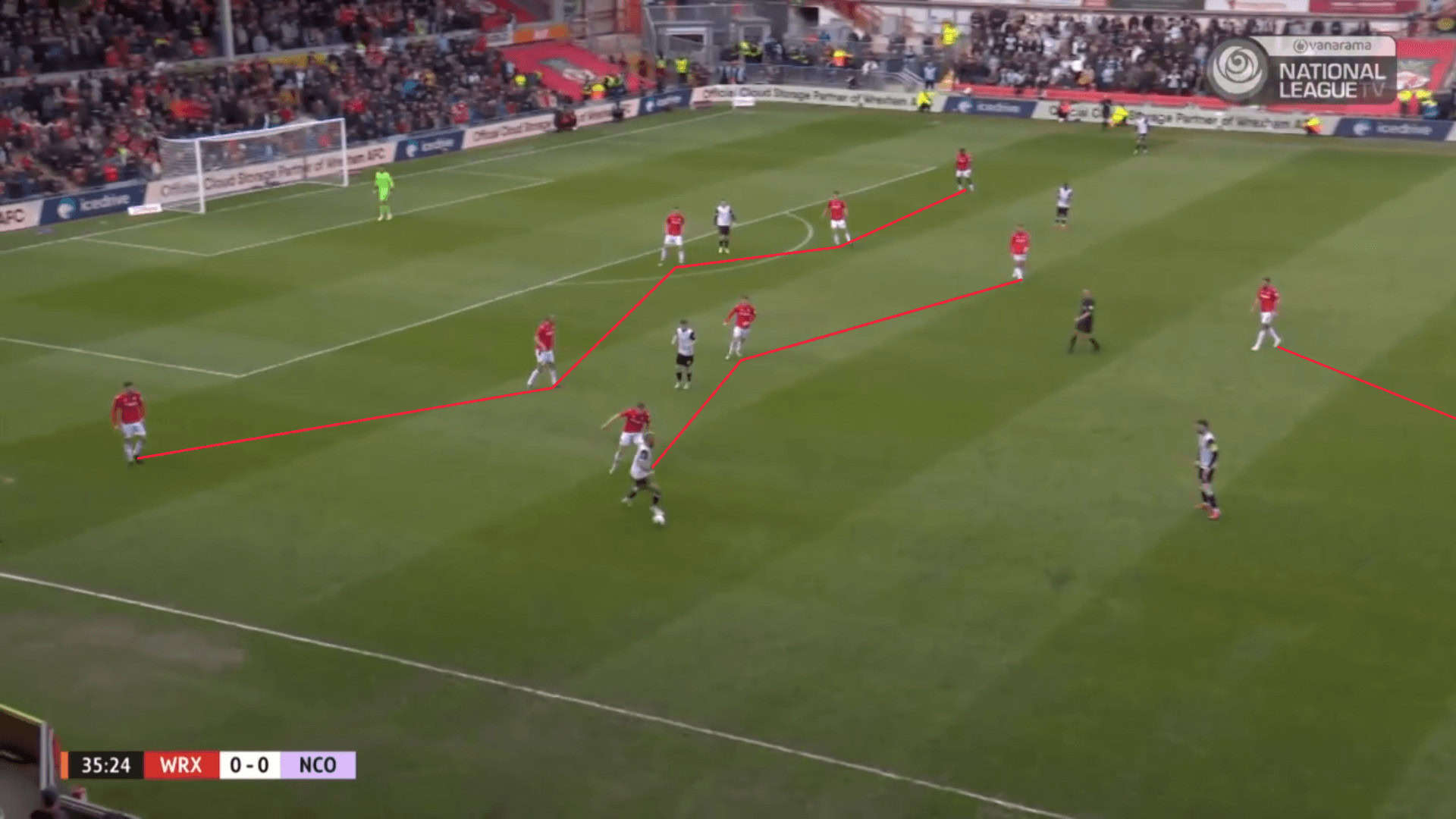

Near the end of the first half against Notts County, we have a nice view of Wrexham’s high press. Notice their numbers in the image relative to Notts County’s. Only the right-winger is out of the picture for the Red Dragons whereas Notts County only has five players. Wrexham’s two forwards are tightly connected, as are the three midfielders. The forward and midfield lines are approximately 25 m apart, which is rather significant, but the back five and midfield three are very tightly connected to contest first and second balls, as well as any entry pass played on the ground. Their pressure produces a high recovery, so mission accomplished.

Despite the gap, what they have managed to do is keep play in front of the majority of the team. The lines are highly concentrated horizontally, yet man and ball oriented in terms of their verticality. The pass from the goalkeeper was played on the ground into midfield and turned over under heavy pressure. The first line forced the pass and the next two lines were positioned to contest the goalkeeper’s delivery. Ultimately, it was a well-executed high press for Wrexham.

The distance between the first two lines is not a consistent trend, but a tactic they could implement on the fly. The high positioning of the Notts County goalkeeper, Sam Slocombe, which was consistent throughout the match, forced Wrexham’s hand to run with the larger gap between the two highest lines.

Against a more standard build-out, as seen against Boreham Wood, the press was more tightly connected. The key point here is the way Wrexham condensed the field’s playing surface. Once play was funnelled into the wings, the Red Dragons were very quick to get numbers near the ball. The short options were non-existent and shadow marking complicated access to the intermediate targets.

That aggressive high press forced play long. Since a long pass was anticipated, Wrexham won the first ball. The second ball was picked up by Boreham Wood, but Wrexham had so many numbers around the ball that he was under pressure immediately and the ball was put out of play.

One of Wrexham’s central tenants when out of possession is to keep numbers behind the ball. The five in the back and three in midfield consistently hustled into their positions to limit the opponent’s success moving forward. As the opponent’s attack slowed in the final third, that’s when you might see one of the Wrexham forwards drop in to give them a 5-3-1-1 shape. With him dropping deeper, it made it easier for the side to limit the opponent #6 and gave them an outlet on a fourth line if the ball was won or cleared.

Their league-leading xGA and third-best mark in goals allowed was a product of a team-wide commitment in defence. Central orientation to funnel play into the wings and then condense the playing area made them difficult to break down. The commitment of the players to get behind the ball only complicated the matter. You could argue they were the best defensive side in the National League. As they move into League 2, that defensive dominance must come with them.

Wrexham’s promotion – what to expect in League 2

The season is finished and the league won, so focusing on the past has limited bearing on Wrexham’s future. They’re moving up a division and will face many of the same struggles that newly promoted teams must endure. Summer transfers may help their chances of either staying in League Two or even fighting for promotion to League One as early as next season. Unfortunately, Gareth Bale, the former Real Madrid and Tottenham star, is reportedly not interested in signing for the club, but the signing of Ben Foster could spur other stars to sign on the dotted line.

Though Wrexham’s transfer market moves are yet to be determined, what we can do is look at the current squad’s performances in the National League relative to the league averages in League One. To give those averages more context, what we’ve done is given stats for the first five tiers of English professional football. That will give an idea of where Wrexham was relative to the National League, some idea of how they could fare in League One and shed light on the relationships between the top five leagues.

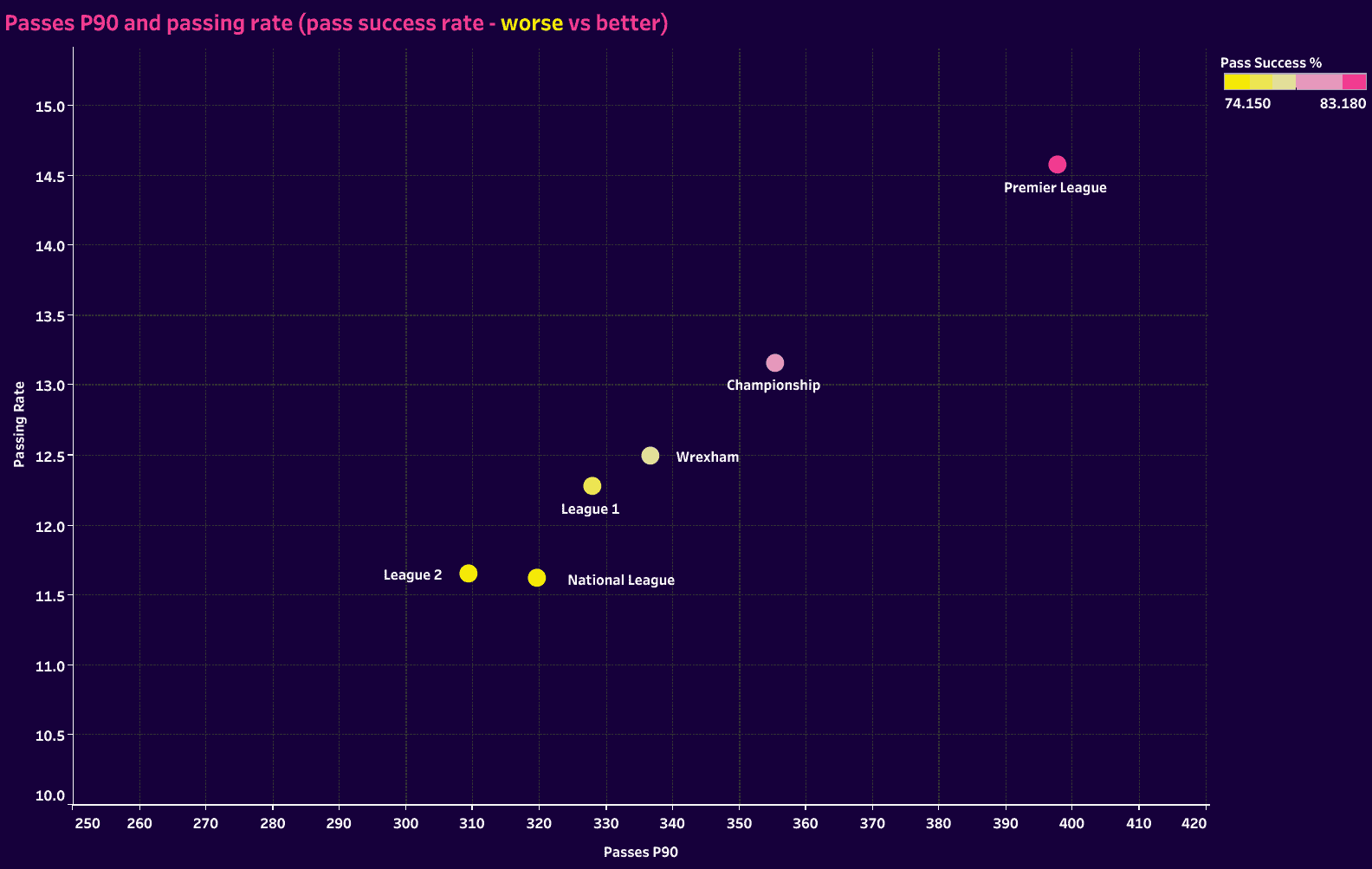

We’re going to focus more on how play is constructed in each of these leagues. We want to gauge some of the more basic constructs of play. The first statistics we’ll look at are passes p90 and passing rate, which is the average number of passes completed in one minute of possession. Adding another wrinkle, passing success percentage is indicated by the shading of the points on the chart. The more full the yellow, the lower the percentage. The deeper the pink, the better the passing.

As anticipated, unsurprisingly, the EPL is in a league of its own. The Championship has significantly better numbers than the other three leagues, but notice it’s Wrexham that stands between League One and the Championship. That’s in both passes p90 and passing rate. Again, these are averages across all five leagues, so we’re not looking at league bests, but it’s certainly a positive for Wrexham to rate this high on the chart.

Across the globe, the lower leagues are known for more direct play. The technical and tactical disparity between the top divisions and the lower levels is significant. Lower league teams simply can’t play with the same technical and tactical demands as top-division clubs. The way the ball is progressed will inevitably vary across the divisions.

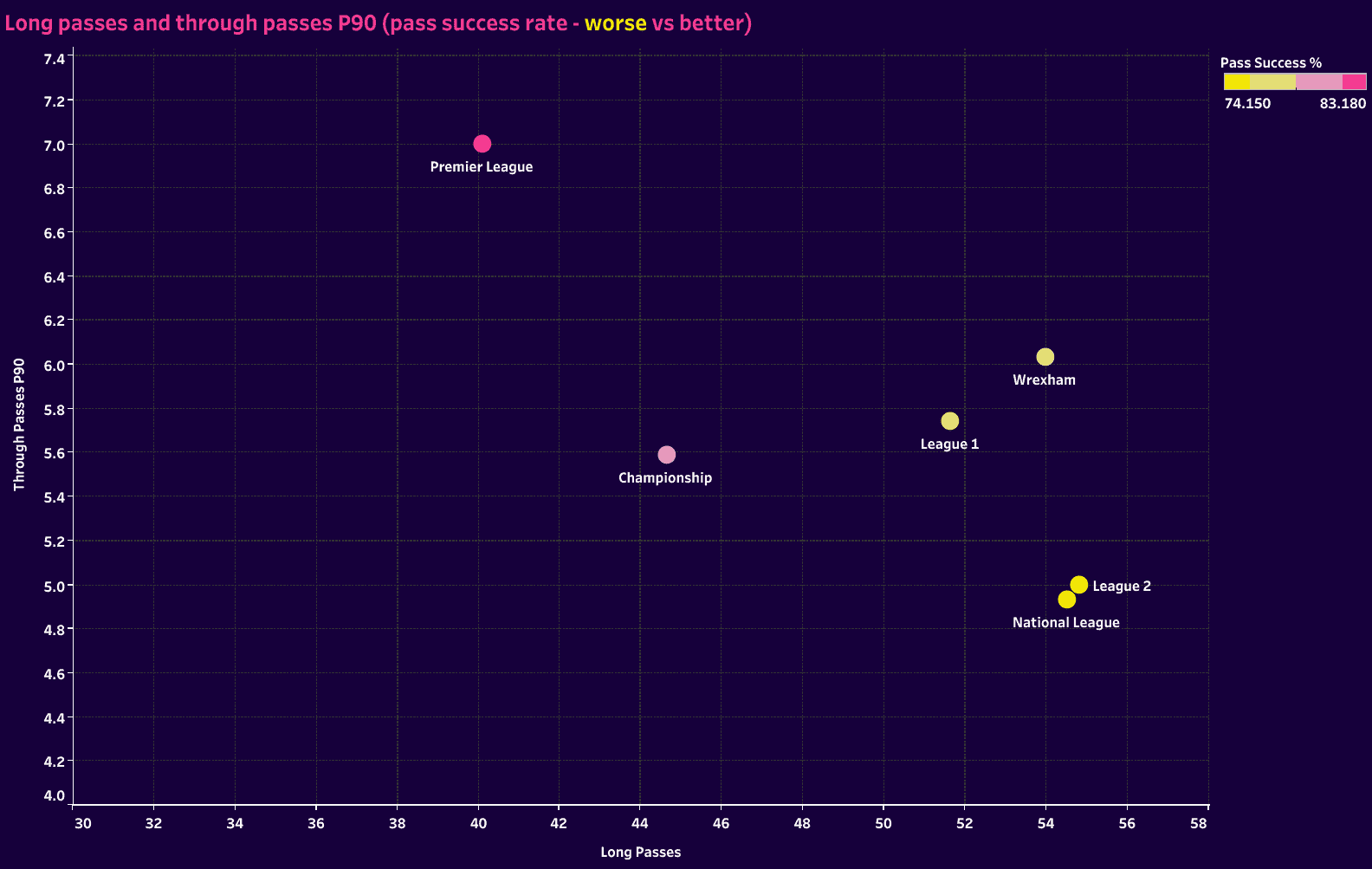

Looking at through passes and long balls P90, the EPL is again on its own, sending far fewer long passes on average and more through balls. This makes sense given the level of difficulty to complete a through pass relative to a long ball. Surprisingly, League One attempts more long and through passes than the Championship on average, whereas League Two and the National League are nearly identical.

Perhaps the greatest surprise in this graphic is that while Wrexham attempts slightly fewer long passes than the National League average, they attempted far more through passes. To give context to Wrexham’s 53.99 long passes attempts P90, in the UEFA Top Five leagues, only Bochum, Werder Bremen and Mainz 05 attempt more. Your fun fact for the day is that eight of the top 11 clubs in long passes P90 across UEFA’s Top Five play in the Bundesliga and another is Liverpool, coached by a German.

In terms of constructing play, the relationship between these two statistics will be very interesting to watch next season. Without knowing the players who are coming in, assume the current squad would play fewer through passes and possibly see an uptick in long-range deliveries.

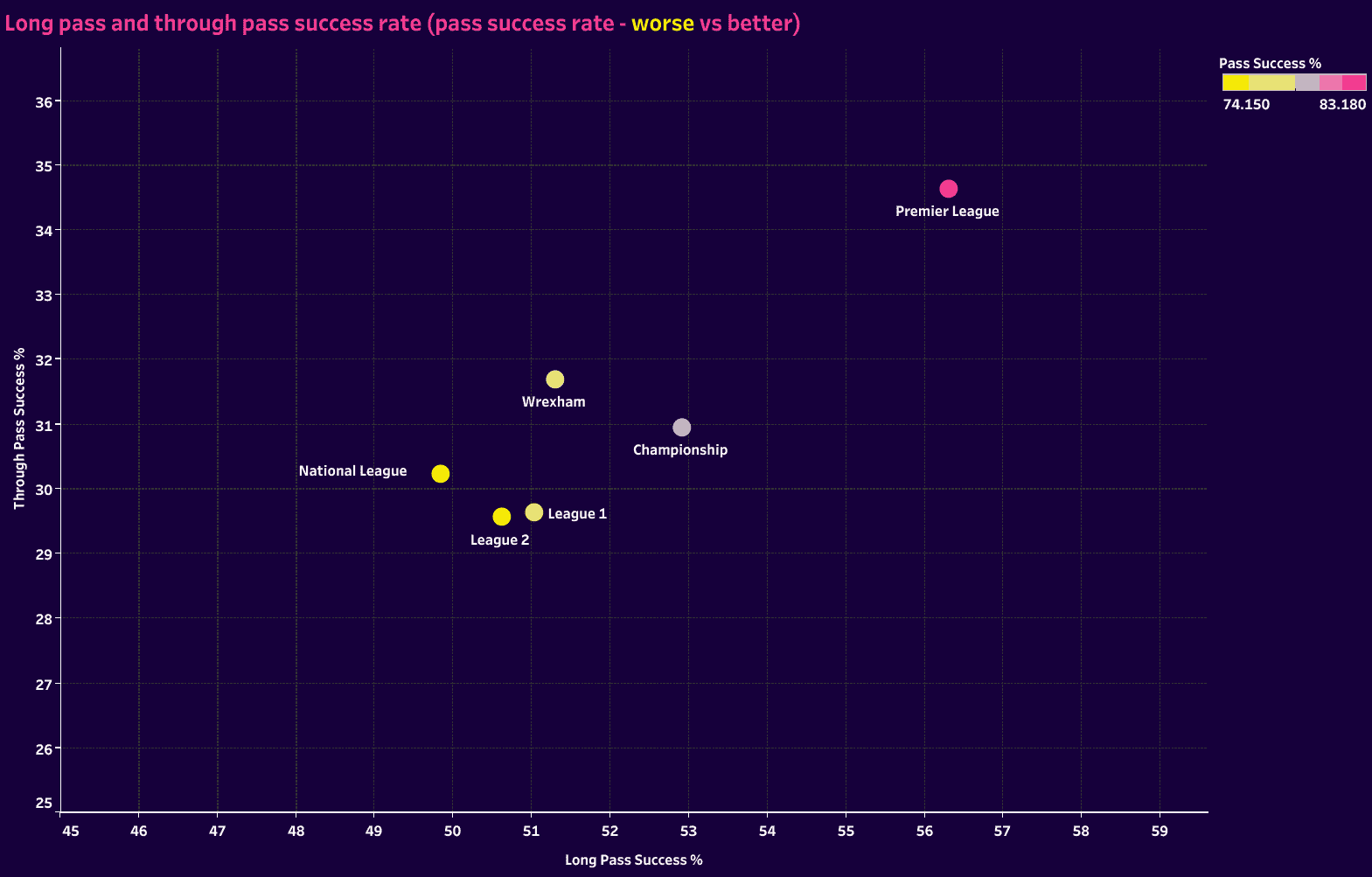

Now let’s turn to the success rate of each of these passes. We’ll leave the Premier League alone and focus on the other four plus Wrexham. In terms of success rate, there’s very little difference in the other four leagues. The Championship has a 1.88 advantage over League One in long pass success rate, but through passes are very close between the four. Wrexham outperformed the averages in each of the four leagues in through pass success percentage and beat those bottom three leagues in long pass efficiency.

Again, with the promotion to League Two, facing better competition should lead to slight decreases in efficiency across the board. A decrease in efficiency could also have an impact on the number of attempts and completions in each category. That said, Wrexham should be very pleased with their rankings relative to those bottom three leagues.

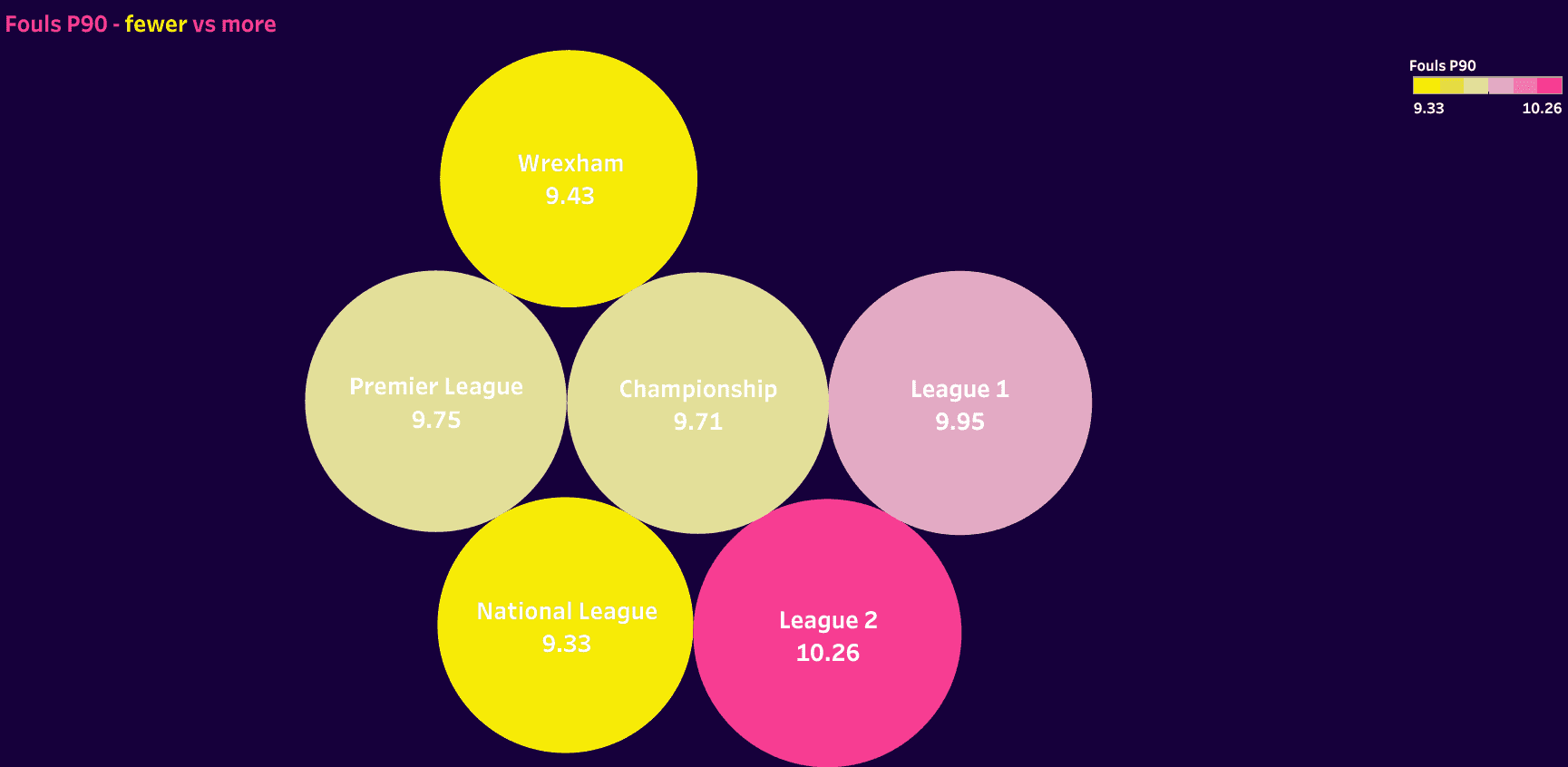

The last statistic we’ll look at is fouls P90. I’ll never forget my first experience of National League football. In fact, it was the Wrexham versus Notts County game while researching for this article.

As Notts County prepared to kick off the game, the referee blew the whistle to signal the start. Within one second, a second whistle had sounded. The game’s first foul.

Given the lower leagues have a reputation for physicality, we decided to look into the fouls P90 across each league. Surprisingly, there’s very little difference. League Two was the category winner with an average of 10.26 fouls P90, beating League One by 0.31. There’s not a tremendous difference in the numbers, but Wrexham should expect slightly more physical play next season.

Another point of comfort is that we’ve already seen this Wrexham side perform very well across two legs against Sheffield United, who have just secured a return to the Premier League as EFL runners-up. Though Wrexham was understandably more defensive and reliant on set pieces in the tie, they will take comfort in knowing they can play with opponents in the next division.

In that first cup game against Sheffield United, the one that ended 3-3, it was Wrexham who had a 3.14 xG and 20 total shots that outperformed Sheffield’s 1.66 xG and 13 attempts on goal. The second leg saw Sheffield United have the better of play, but Ryan Reynolds’ and Rob McElhenney’s side managed to stay in the game until the dying minutes. Not the result they wanted, but certainly a positive sign as the club prepares for life in League Two.

Conclusion

The ambitious Welsh club had the perfect season. Promotion to League Two while winning the league and pushing Sheffield United in a highly entertaining FA Cup tie was exactly the drama Wrexham fans wanted. 2022/23 also saw the club set National League records for wins, points and fewest losses in a season. Surely a first league title in 45 years was enough to galvanize the owners and captivate the millions following the team and watching the documentary.

As Wrexham prepares for their first League Two season in 15 years, new signings will surely arrive, but Ryan Reynolds, Rob McElhenney, Phil Parkinson and the fans, especially the lifers, will relish the memories of this extraordinary season.

The future is bright in Wrexham. The world awaits the next big news from the club, as well as the next season, both in League Two and on “Welcome to Wrexham.”

Prepare for drama. Welcome to League Two.

Comments