On 27th February 2023, certain members of the football world were given a shot of excitement that left them salivating. Those people were the devotees of ‘Zemanlandia’. It was announced that Czech-Italian coach Zdeněk Zeman, or ‘Il Boemo’ as he’s affectionately known, was returning to the dugout at one of his former clubs, Delfino Pescara 1936, until the end of the season. The 75-year-old is now in the midst of his third spell in charge of I Delfini.

‘Zemanlandia’ is used to refer to his distinctive attacking style of play and innovative tactical approach, sure, and we’ll get on to that. But it’s also seen by some as a whole way of being that’s defined more by the man and his combative, outspoken personality and general mannerisms than anything else. So just by watching Zeman and becoming familiar with him, you get an idea about what the cult-following he’s garnered over the years is so enamoured by.

“Football is more and more an industry nowadays and less and less a game. In football, there are no more flags; the control is now in the politics and the economy” — Zdeněk Zeman

From coffee and cigarettes on the touchline to creating media controversy, Zeman is exactly the kind of personality, win, lose or draw, that ignites a fanbase and draws the passion out of them, often directing shots at those pulling the strings at the top of the game.

Our tactical analysis article will discuss why and how Zeman has become such a legendary figure in the game whose work is followed and admired by many — fans and coaches alike. We’ve picked out three distinct eras from his career which together, we feel, help to paint a clear picture of Zeman’s ideas and philosophy.

There are a lot of quotes of his to choose from to sum it all up but as we’re moving on into the tactical analysis portion of this article and transition from the man behind the football, let’s finish off the intro with this one that says a lot about what we’re going to see any time we watch a Zeman team take to the pitch:

“If you score 90 goals then it shouldn’t really worry you how many are conceded”.

Calcio Foggia, 1991/92

We’ll kick it off with the place where it’s widely viewed Zeman first shot to real stardom in the public eye: Calcio Foggia 1920.

At 42 years of age — having spent the formative years of his coaching career as a Palermo youth coach before moving on to take his first head coach position at Licata, then Foggia, Parma and Messina, respectively — Zeman returned to Foggia for a second spell with ‘Satanelli’.

This would prove to be a brilliant decision by chairman Pasquale Casillo, as Zeman would, from here, go on to forge one of the greatest stories in world football from the 1990s, as the 2009 documentary ‘Zemanlandia’ depicts.

Starting in Serie C1, Zeman’s side would earn back-to-back promotions, ending up in Serie A for the 1991/92 campaign. This is where we pick things up and analyse his approach with the 1991/92 Foggia team that achieved a highly respectable ninth place in the league despite being viewed by many as one of the division’s weaker sides. How is this possible?

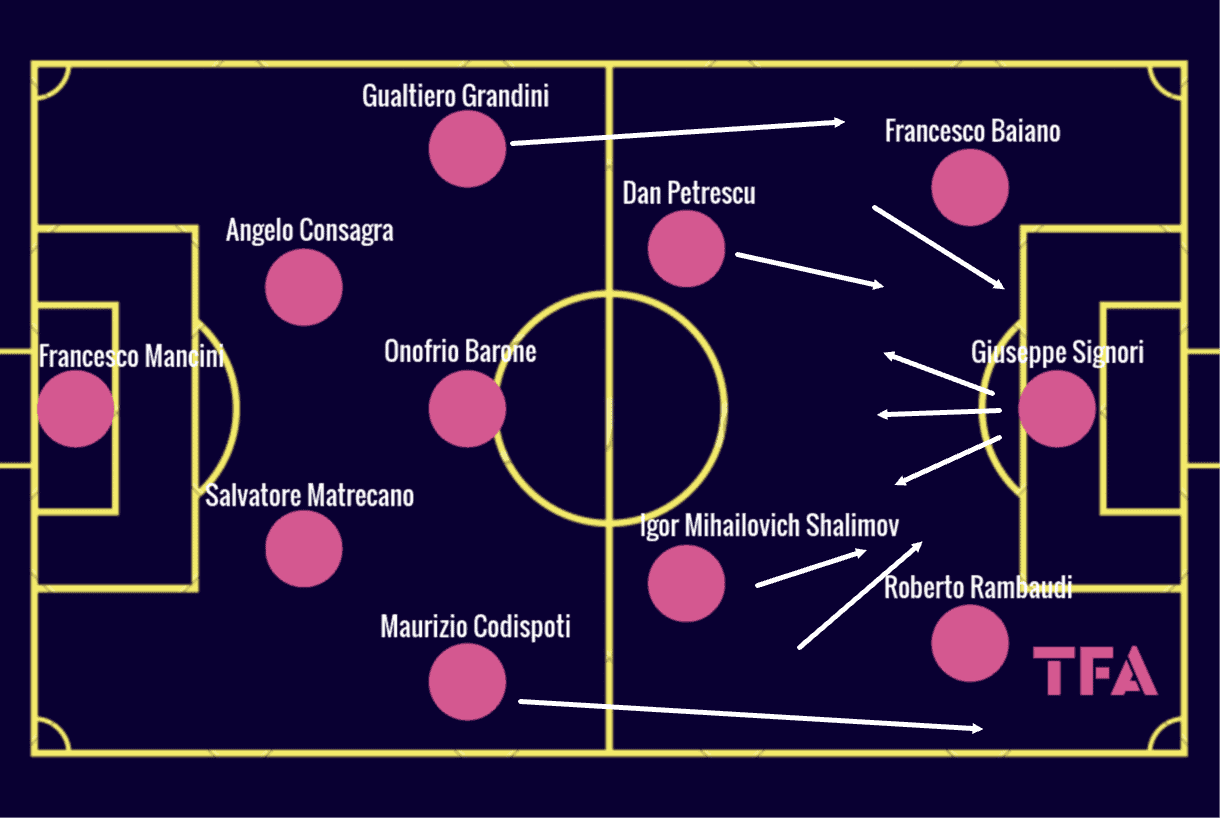

Little changed in Zeman’s Foggia side from the previous campaign in Serie B to the 1991/92 campaign in Serie A. However, with foreign nationals only being allowed to play in Italy’s top flight back at this time, not the lower divisions, there was a sprinkling of talent added to midfield in the form of Romanian Dan Petrescu signed from Steaua București and Moscow-born Igor Mihailovich Shalimov, signed from Spartak Moscow.

This is the first Zeman team that shot to the limelight and it provides a basis for what we’ve seen from the Czech-Italian’s teams over the years. Firstly, we see this base 4-3-3 shape with two more offensive midfielders on either side of a holding midfielder. Zeman’s teams have typically lined up in this fashion over time.

The full-backs getting forward, overlapping and contributing to the attack, positionally and/or numerically overloading the opposition’s backline are a common feature of the legendary coach’s teams over time too, with that being marked out on figure 1 above. In order to play full-back in Zeman’s 4-3-3, you must not just be a good defender, you have to be able to offer a lot going forward.

The central midfielders do a lot of water-carrying. They’re required to be box-to-box, getting up and down the pitch, contributing goals at one end while breaking up the play at the other. So, the new boys, Petrescu and Mihailovich Shalimov had to get up to speed with the manager’s style of play quite quickly on arrival in Italy.

Inside forwards are a common theme in Zeman’s tactics, as we see here. It’s not uncommon to see one of the wide men being basically a centre-forward positioned out wide who can push inside and team up with the actual centre-forward in the box at times, while the other wide man is more the artist, the creator with free rein to roam about, find space, get on the ball and make things happen.

In this case, however, it was more Signori, who Zeman had converted from a winger to a centre-forward in the first place, who was given this ‘star man’ treatment and performing the roaming about, in a sense. He often dropped deep to occupy pockets of space where a ‘10’ might be found, thus opening up space for the two wide men to come inside and attack.

As a result, Rambaudi and Baiano effectively operated as two typical inside forwards. They were encouraged to come narrow, creating space for the overlapping full-backs, take on full-backs on the ball and attack space opened up by Signori’s movement off the ball.

Hard work was required from everyone in this Foggia team because Zeman demanded a super high-octane pressing game. He wanted the team to win the ball back quickly and transition quickly, with an ideal vision of relentlessly peppering the opposition’s goal and giving them no time to build an attack of their own. They liked to move the ball quickly and dominate possession while giving their opponents none of the ball.

Of course, this wasn’t a foolproof plan. It had and has drawbacks. For instance, Foggia’s players had to have an incredibly high level of fitness to maintain their intensity over the course of the game and even then, it was natural to see silly mistakes creep in (poor positioning, needless fouls, misplaced passes, etc.) as a result of fatigue later on in games, while space was quite open behind their high backline.

But then, every football tactic has its strengths and weaknesses. What we can say for sure is that with back-to-back promotions followed by back-to-back top-half Serie A finishes for a team considered ‘weaker’ than many of their competitors in the league, Zeman’s tactics certainly got the best out of his players — and created a legendary story in the process!

AS Roma, 1997/98

Fast forward to Roma in 1997/98, and we find what is widely regarded as Zeman’s magnum opus — the team that perhaps provides the best example of his tactics with the highest quality of player available.

This team only managed to finish in fourth place in what was a very competitive league won by Juventus that season, but they produced some scintillating football worthy of the cult hero masterminding it all.

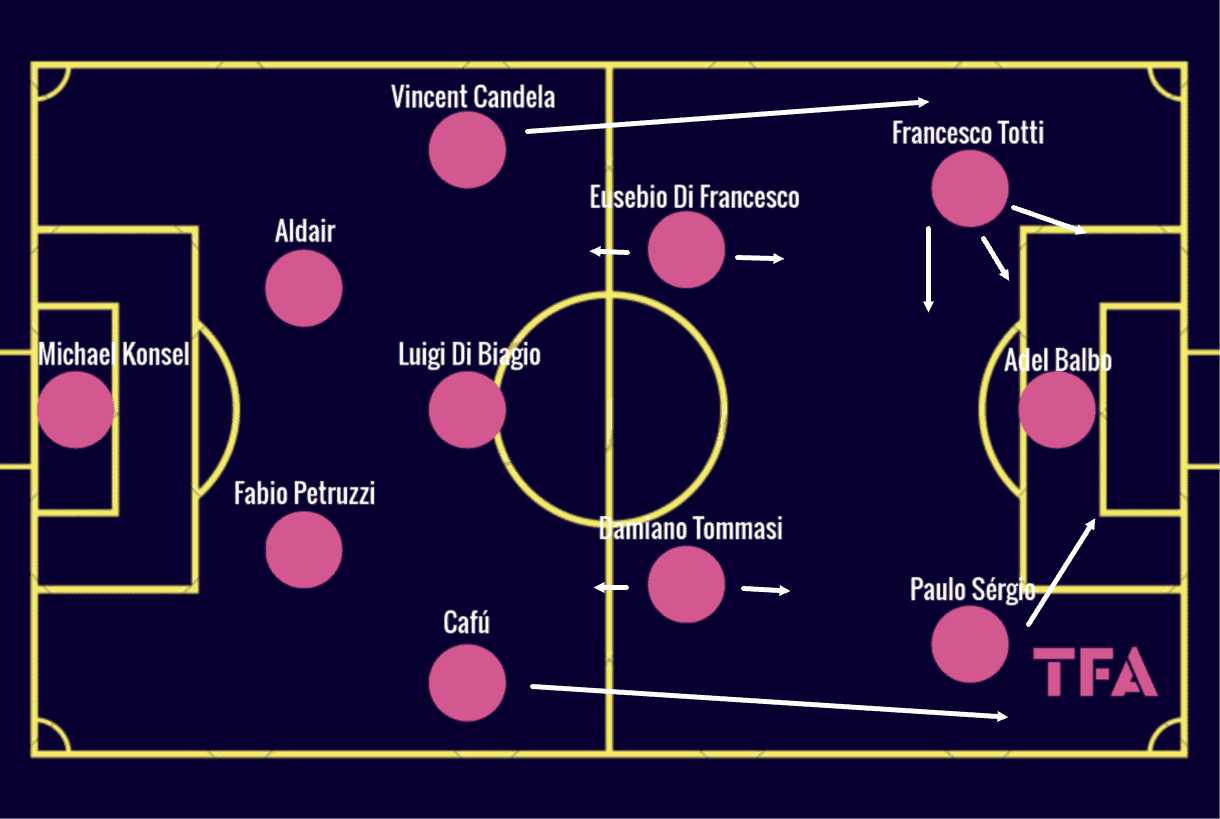

In this team, Totti was the maestro in the forward line given the licence to roam about a little, find space and exploit it. Balbo is an example of a typical Zeman centre-forward that we’ve seen at several clubs over the years, in that he’s a well-rounded attacker, capable of finishing in a variety of ways, who’s as quick as he is strong. Meanwhile, Sérgio on the right was a little more direct than Totti and acted as more of a partner for Balbo than a ‘10’ like Totti.

One of my personal favourite aspects of this squad is the full-backs. You have three FIFA World Cup trophies on those flanks (one for Candela, two for Cafú). This full-back pairing perhaps best facilitated Zeman’s vision for the full-backs in his ideal tactical setup more than any other pairing the Czech-Italian has had at his disposal during his career.

This campaign was Cafú’s first in Europe, moving from Palmeiras in the summer of 1997. He’d remain at Roma for six years before joining AC Milan where he’d become a UEFA Champions League winner. His European adventure began under the guidance of Zeman, and this was a match made in heaven.

Under Zeman, Cafú was encouraged to maraud forward constantly, fill the gaps left vacant by the inside forward ahead of him on the outside, overload the opposition’s backline and create chances. The Brazilian right-back was very well capable of this, as was French World Cup winner Candela on the other side. Together, they provided a constant threat on the flanks which, when combined with the front three ahead of them, made Roma a terrifying team in offence.

In midfield, Di Francesco and Tommasi embody what Zeman really wants from his midfielders first and foremost. While technical ability is important within this system, the primary focus is on hard-working, tenacious, box-to-box midfielders who can provide something at both ends of the pitch throughout the game. These two at Roma delivered that as much as any midfield duo under Zeman’s watchful eye.

This starting XI was Roma’s most-used starting XI over the 1997/98 season, though of course, with such an intense style of play, rotation was key for Zeman. The likes of Marco Delvecchio in attack, Carmen Gautieri in midfield and Antônio Carlos Zago in defence all played important rotational roles for I Giallorossi during the campaign.

This team played Zeman’s typical high-paced game based on relentless pressing, quick transitions and a high-tempo possession game. They loved to commit players forward and try to overwhelm their opponents at the back via the players and player roles discussed above, the highlight of which would be the performances of Totti and the full-backs, for me.

Despite falling short in their quest for the Scudetto, Roma finished the season with the joint-highest goals scored (67). It was their 42 goals conceded (the most in the top seven) that killed their title hopes.

This is the essence of Zemanlandia — high goals scored, high goals conceded. It’s something that would drive a lot of coaches crazy but simply drives Zeman. For fans, it’s certainly entertaining to watch, especially when players like Totti and Cafú are given such freedom within the ultra-attacking system.

Delfino Pescara, 2011/12

Our final study of a Zeman team comes from much more modern times, yet still more than a decade ago! This time, we go to Pescara, where we can once again find Zeman today. In 2011, however, the legendary coach was embarking on his first season, and first tenure, in charge of the Abruzzo-based club.

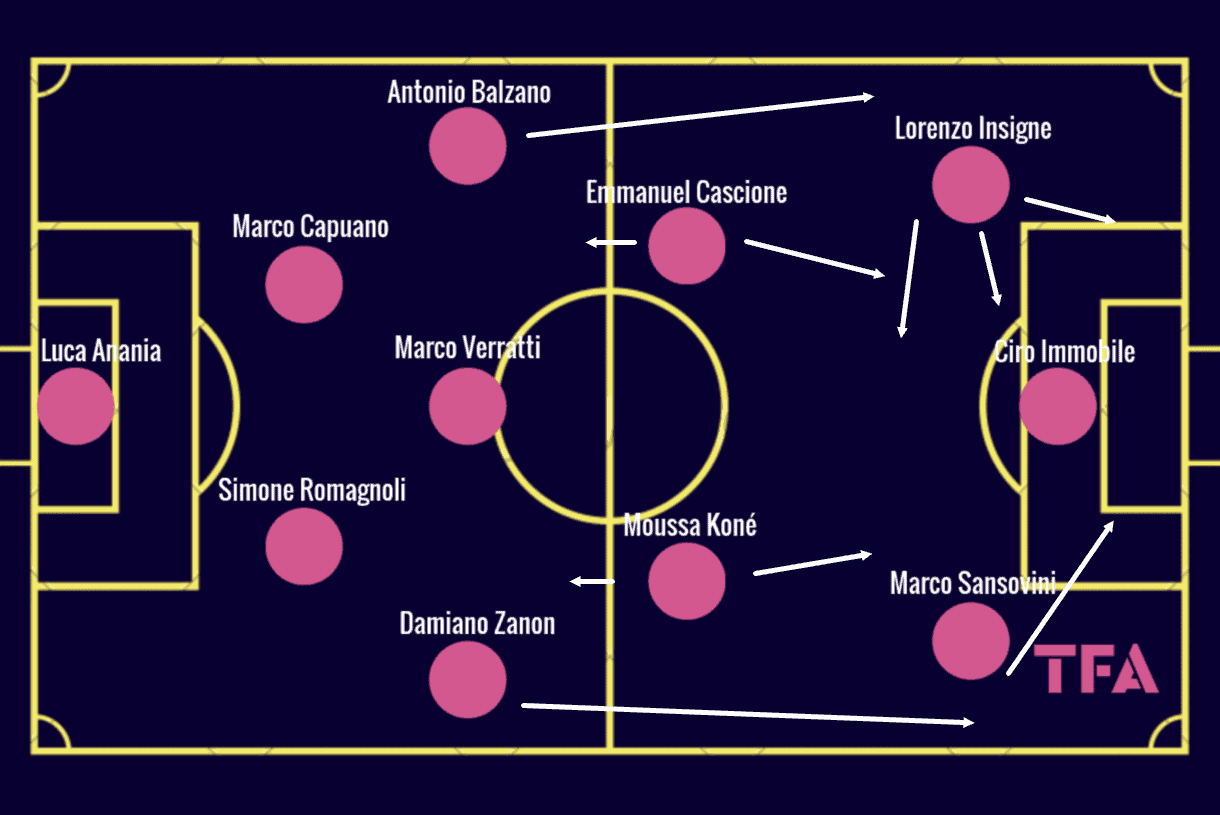

You’ll find a lot of familiar names scattered throughout this team and you’d be forgiven for not realising they were all in Serie B together when Zeman took charge of the club. In his first season, the Czech-Italian guided this group to the title with a whopping 90 goals scored and 55 goals conceded in 42 games resulting in 83 points.

This team didn’t operate that dissimilarly at all to the 1997/98 Roma team. Insigne performed the Totti role, while Sansovini, typically a centre-forward, performed the role of partnering the man up top, Immobile, another player who truly embodies Zeman’s ideal well-rounded centre-forward.

Cascione and Koné, the latter of whom was on loan from Atalanta, were the hard-working midfield duo with decent technical ability that was significantly overshone by their commitment off the ball to carrying out Zeman’s tactical demands. They almost acted as knights on either side of the deep-lying playmaker, Marco Verratti.

The diminutive Italian midfielder famously never played in Serie A, as he went directly from this season with Pescara to Ligue 1’s PSG. This didn’t hurt him, though! It’s a testament to how well he performed his deep-lying playmaker role within Zeman’s 4-3-3.

Verratti has played in a slightly more advanced position in Paris a lot in recent years but back here, he was sat behind his two midfield partners, in front of the backline, required to find space to receive from those positioned deeper a lot, turn and drive his team forward from there.

Both long passes and short passes were major requirements of the deepest midfielder within this 4-3-3. It was common enough to see Verratti pinging the ball over the top for, perhaps, Immobile or Sansovini running in behind and out to the wings for the overlapping full-backs — in this case, Balzano and Zanon.

However, he always had to keep an eye on Insigne’s movement, spotting where the key creator coming inside from the wing would find space and trying to link up with him by playing through the centre more delicately.

This usage of Verratti and Insigne, combined with the traditional Zeman player roles explained and how they were applied within the context of this team, pretty much defined the Serie B champions of Pescara in 2011/12, surely one of the Italian second-tier’s best ever teams to watch.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we hope this analysis of three historical Zeman teams provides some greater insight into why there’s such a cult following behind the 75-year-old manager and his tactical ideas. His football is what many would consider beautiful, while his teams undoubtedly play a high-octane, entertaining style.

The words of one of his former players — one who owes him a lot — says more than I could about Zeman:

“He was fundamental to my career” — Giuseppe Signori

But it’s not just Signori’s career to which the Czech-Italian has been absolutely fundamental, there are plenty of players, some of whom we’ve touched on in this analysis, who were made into better, more complete players during their time under the legendary figure.

In terms of coaching inspiration, then, the likes of Maurizio Sarri, Simone Inzaghi, Marco Giampaolo and Giuseppe Iachini have all cited Zeman as a key inspiration and reference for them in their coaching careers. So, while the Italian game is often painted with the ‘typically defensive’ brush, and there is reason for that, the likes of Il Boemo and his followers show Italy has another way to play the game which can be equally as effective. Variety is the spice of life and the Italian game is dashed with it throughout history.

Comments