At the end of the 2017/18 season, Zenit St Petersburg sat fifth and managed to earn a place in the third qualifying round for the UEFA Europa League. However, it was a disastrous campaign given the expectations every season for the club.

Former Manchester City and Internazionale boss Roberto Mancini was the man who oversaw this mess. By the end of the campaign, Zenit had failed to win the Russian Premier League title for three years straight. Something had to change and so the hierarchy called on an old friend.

Having been the assistant manager to Luciano Spalletti at the Krestovsky Stadium after retiring as a Zenit player in 2016, Sergei Semak was announced as the new head coach. Semak already had experience in the hot seat, acting as the caretaker boss for a brief period following Spalletti’s departure from the club in 2014.

But with other experiences such as Russia’s assistant manager for two years from 2014 to 2016 and FC Ufa’s head coach during the 2017/18 season, Semak came back a more mature tactician.

Fast-forward five years later, Semak has just lifted his fifth-straight title with the Russian giants and has fully cemented himself into the club’s history books.

With a squad full of Brazilian talents and one that blends youth and experience, Semak’s team won the Russian Premier League this season in style once more.

This tactical analysis piece will be an analysis, looking at how Semak’s tactics guided Zenit to the title for the fifth-consecutive season.

Risky build-up play

The team’s style of play is a blend of positional and functional. As we are about to analyse, during the build-up phase, Zenit’s set-up is positional, with players adhering to strict principles about how to play out from deep to bypass the opposition’s press.

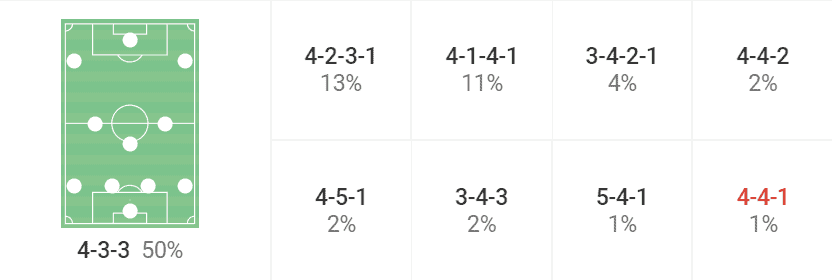

Semak still uses formations as a reference point for his players but the formation is only really seen during the more ‘positional’ phases of Zenit’s play and during the defensive phase. This season, Russia’s champions have primarily lined up in a 4-3-3, although the 47-year-old hasn’t been afraid to chop and change the structure in certain games throughout the campaign.

This was quite different to last season’s most used formation which was a 3-4-3. Zenit lost Dejan Lovren in the summer as the former Liverpool defender returned to Lyon. However, the former Europa League winners did replace Lovren’s experience with the youthful Robert Renan, who was being tipped for greatness back home in his native Brazil.

However, higher up the pitch, especially in and around the final third, the side’s style becomes more functional as Semak takes off the shackles and allows his players to create opportunities according to their own interpretation of space and relationships with teammates. Formations become irrelevant at that point in time.

Semak believes that constantly having the ball is the best way to achieve this, hence why the Russian Premier League champions have registered 60.4 percent possession on average in the league, more than any other side. Spartak Moskva are in second place with 57.4 percent.

Zenit have some wonderfully gifted players in their ranks, particularly players in the backline and the midfield who are comfortable when playing out from the back. This gives Semak the confidence to allow his players to play through a press rather than over or around it.

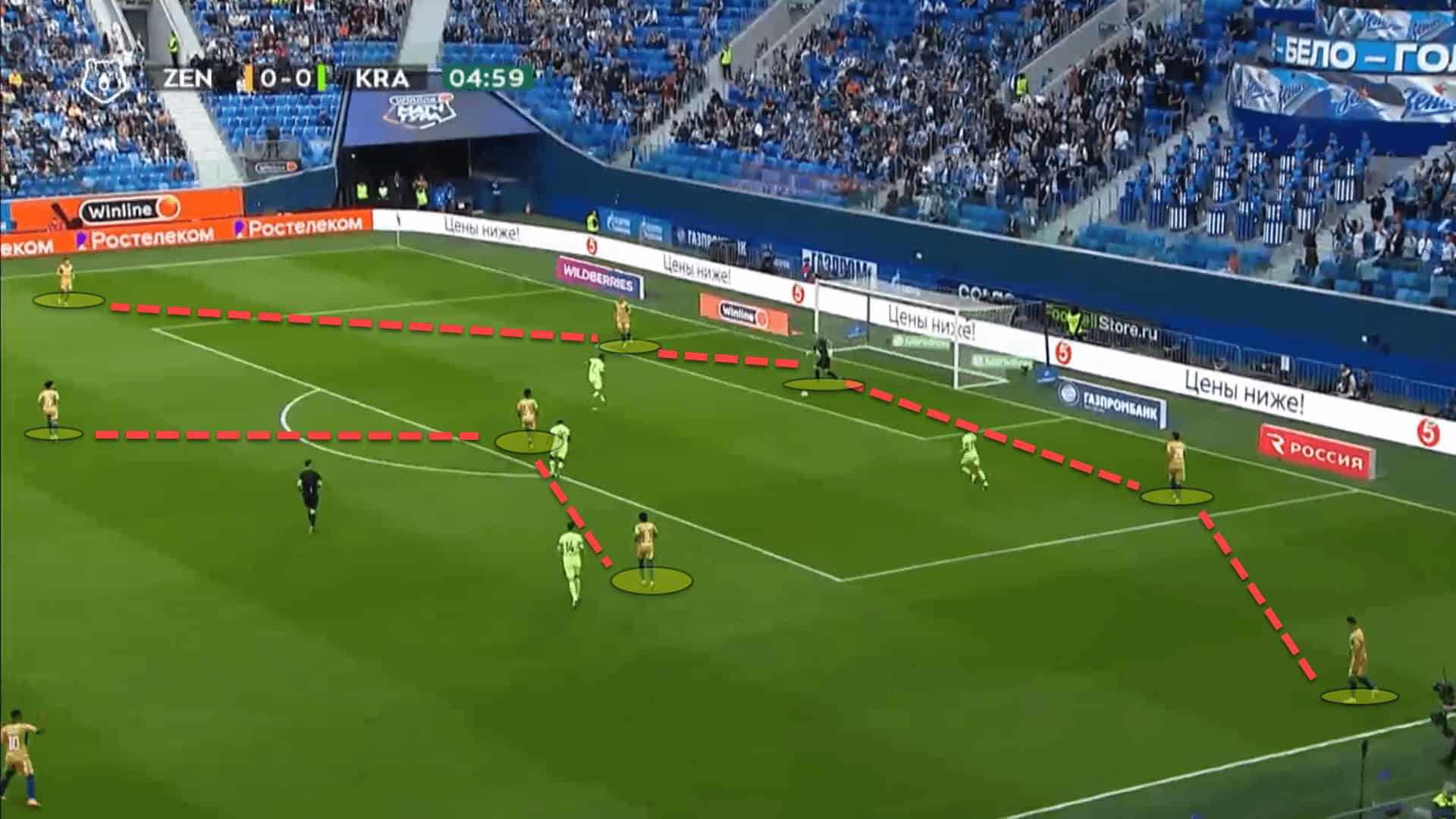

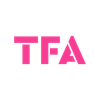

Zenit’s build-up structure is quite symmetrical. Semak wants to have the same passing options on both sides of the pitch and the 4-3-3 formation offers him the ability to bring this to fruition more so than any other shape.

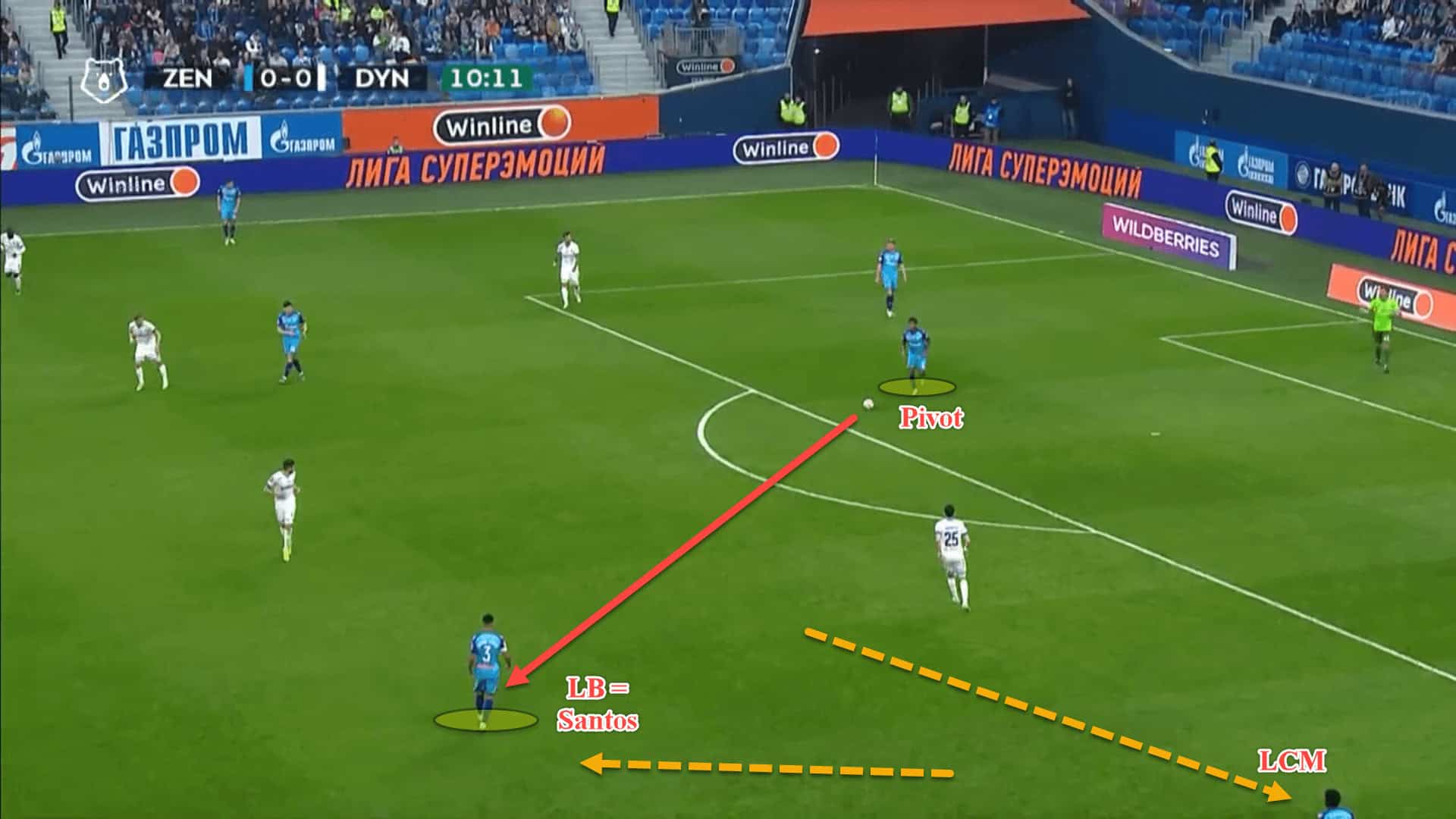

As is highlighted in the previous screenshot, the fullbacks remain low while the centre-backs split the goalkeeper, acting as a square passing lane on either side of the man with the gloves. Meanwhile, the single pivot operates behind the opposition’s first line of pressure and is supported on his left and right by the two advanced central midfielders.

These advanced midfielders, or number ‘8s’, position roughly around the halfspaces on either side of the pitch and can create triangles with the nearest centre-back and fullback, forming the symmetry Semak craves so much.

Things are not always as straightforward as this, though. Zenit’s build-up shape is highly adaptable, which is where we see the more functional aspect of their play come to the forefront. If the opposition’s press is causing the backline problems, it is common to see players take matters into their own hands by manipulating the space behind the press.

What we mean by this is that one of the centre-backs or fullbacks can push up behind the opposition’s first line of pressure to receive the ball, offering another progressive passing option to play through the press if it’s proving difficult to break down.

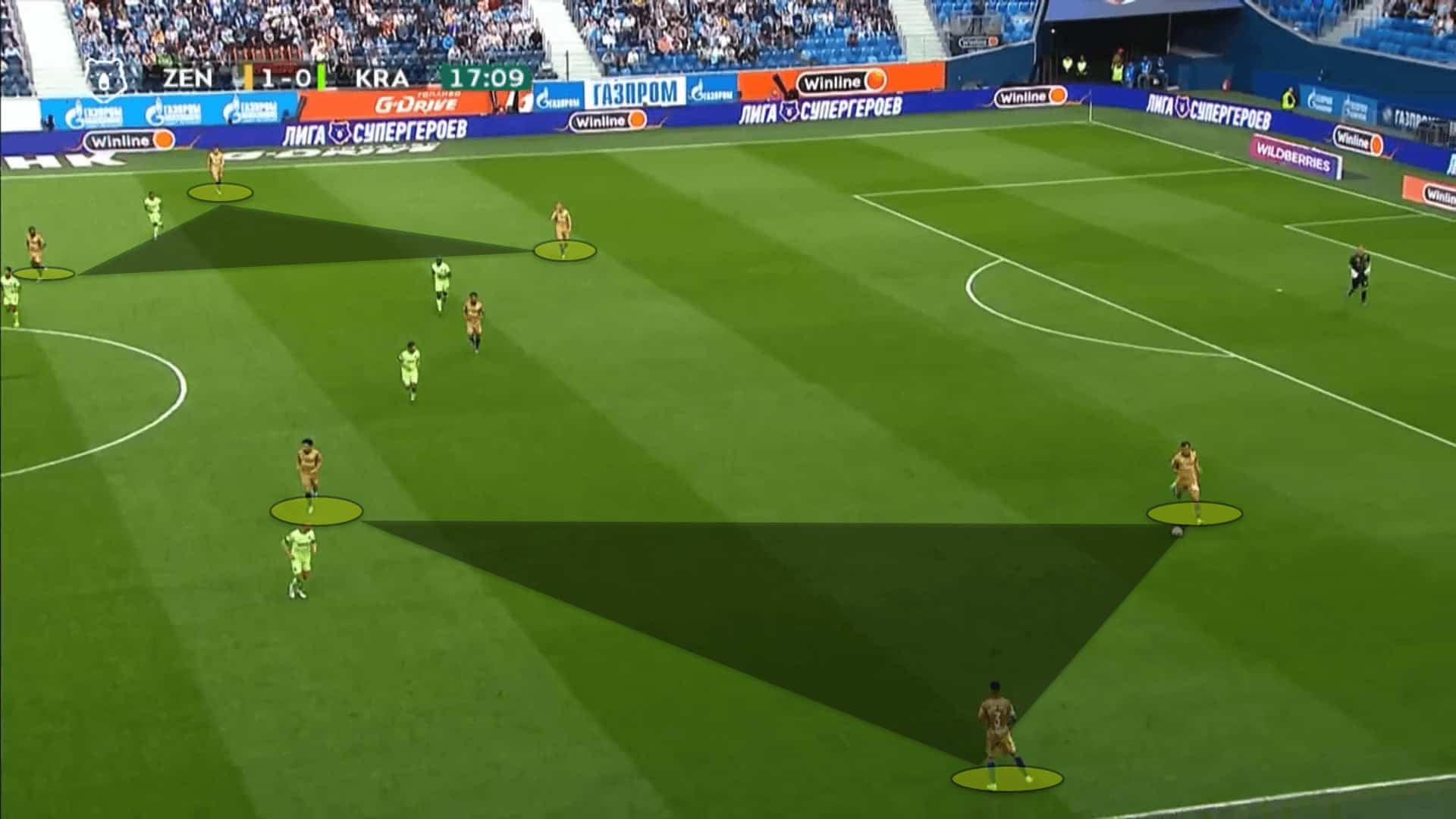

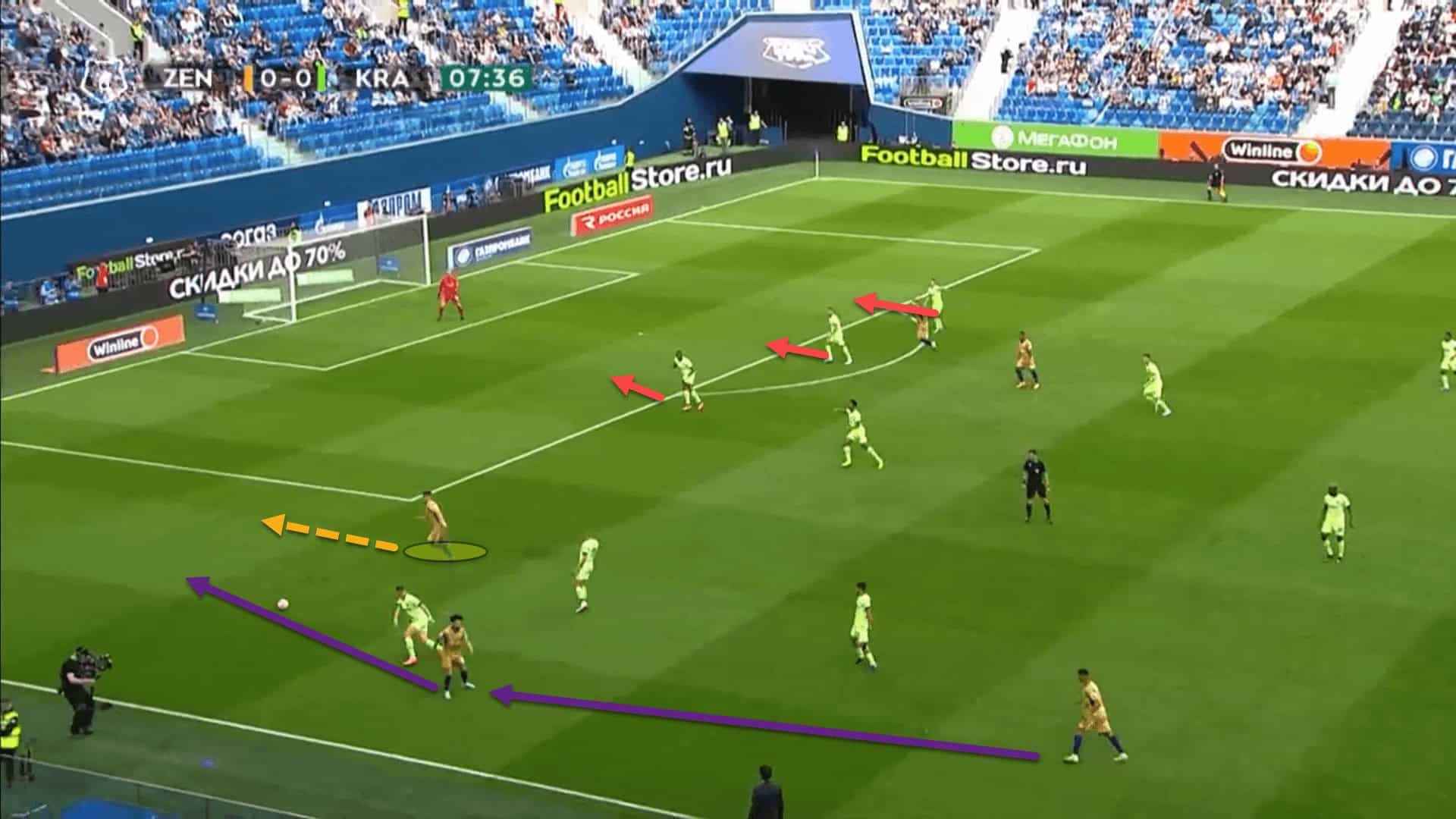

Here, pivot player Wilmar Barrios dropped between the two centre-backs in the first possession line. This allowed him to have more time and space to pick his next pass. Unfortunately, due to his absence behind the first line of pressure, there was a lack of passing options to play to in order to bypass the press.

Noticing the issue, left centre-back Robert Renan swiftly moved behind the opposition’s forward line to give Barrios a passing option, orienting his body perfectly to receive on his stronger left foot.

This is just one example of how Zenit’s play during the build-up phase is incredibly fluid and entertaining to watch and while the side follow the rules of positional play, the positions are not always fixed.

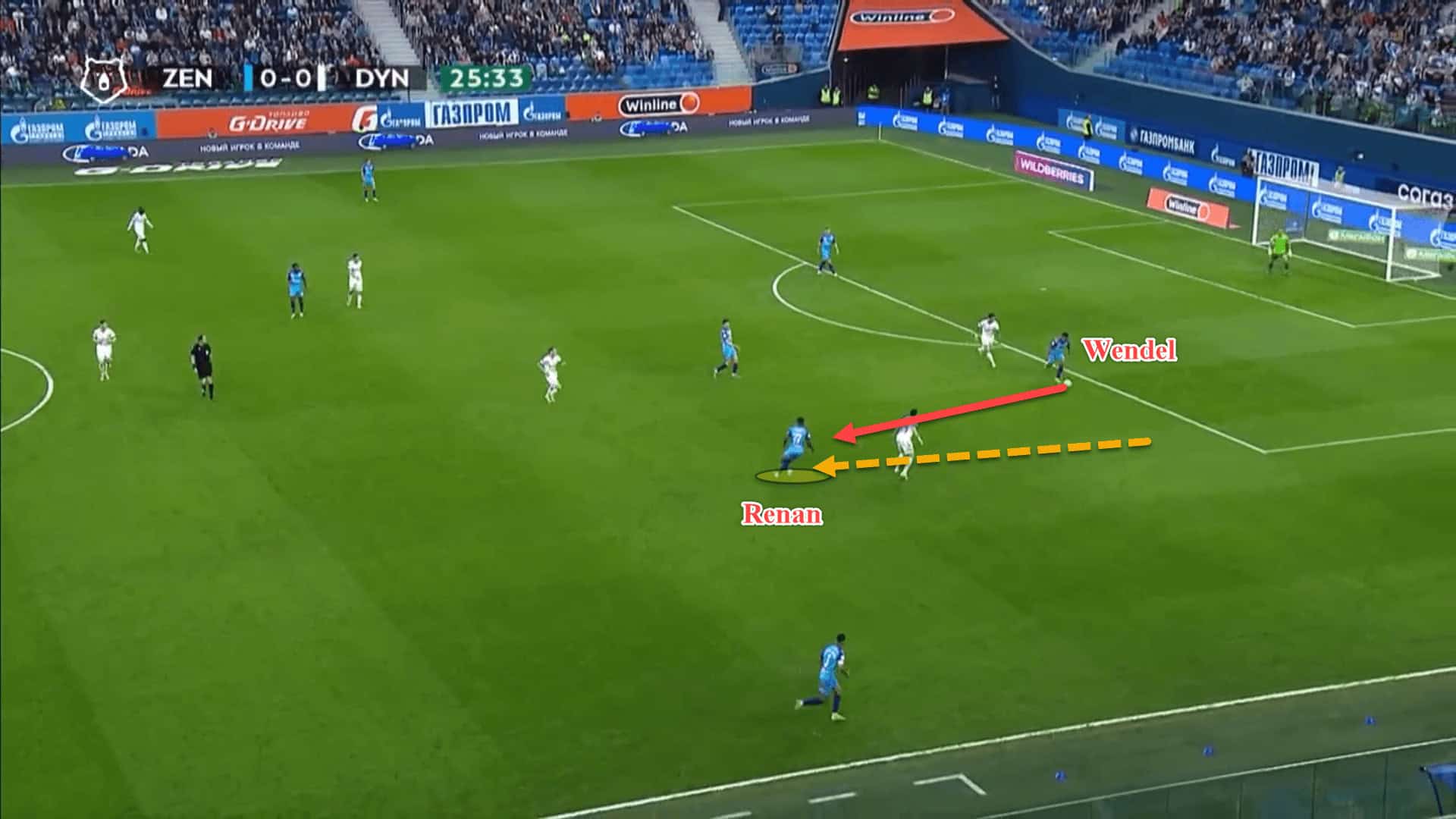

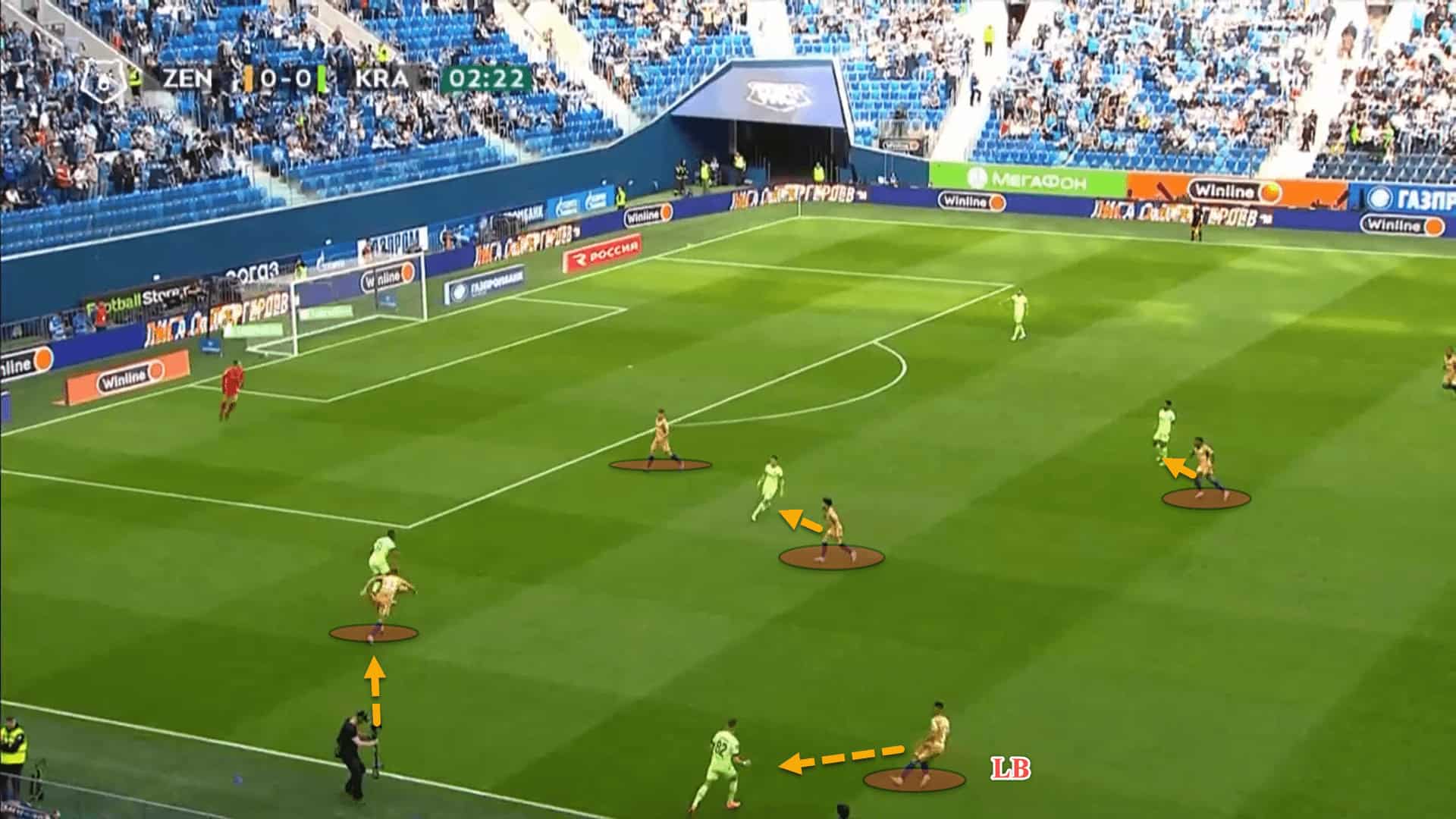

Here is another example of Zenit players interchanging positions to disrupt the space behind the opposition’s first line of pressure. The frontline have not seen the rotation as of when this screenshot was taken which adds to the excellence of the move.

Wendel, the left central midfielder, is naturally right-footed and so the angle to receive from the centre-back was not ideal for a right-footer. To combat this, left-back Douglas Santos, formerly of Barcelona, moves inside as an inverted fullback, swapping posts with Wendel. It is a far better angle to receive for a left-footer who can turn out and drive forward.

Zenit are always trying to break through the opposition’s high press by playing through the central corridors, manipulating the space behind the press to create angles to receive, allowing the champions to progress forward. Semak’s men have registered more progressive passes than any other team in the Russian Premier League this season with 76.6.

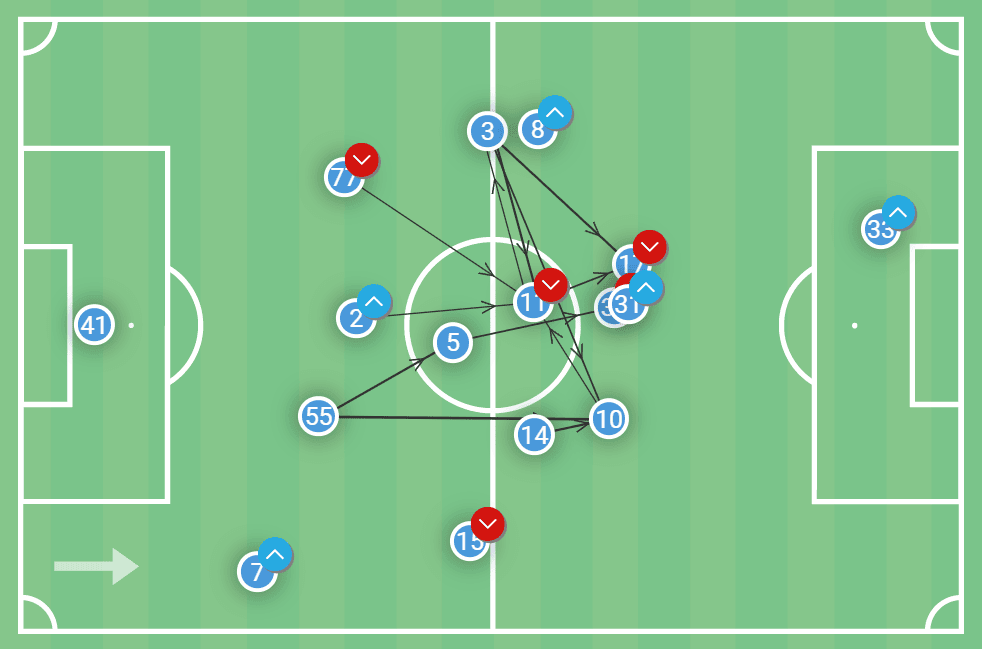

If we take this forward pass map from Zenit’s recent 3-2 win over Spartak Moskva, we can see that so many of their forward balls occur from the defenders playing into the trio in the middle of the park, showcasing a keenness to progress centrally rather than down the sides.

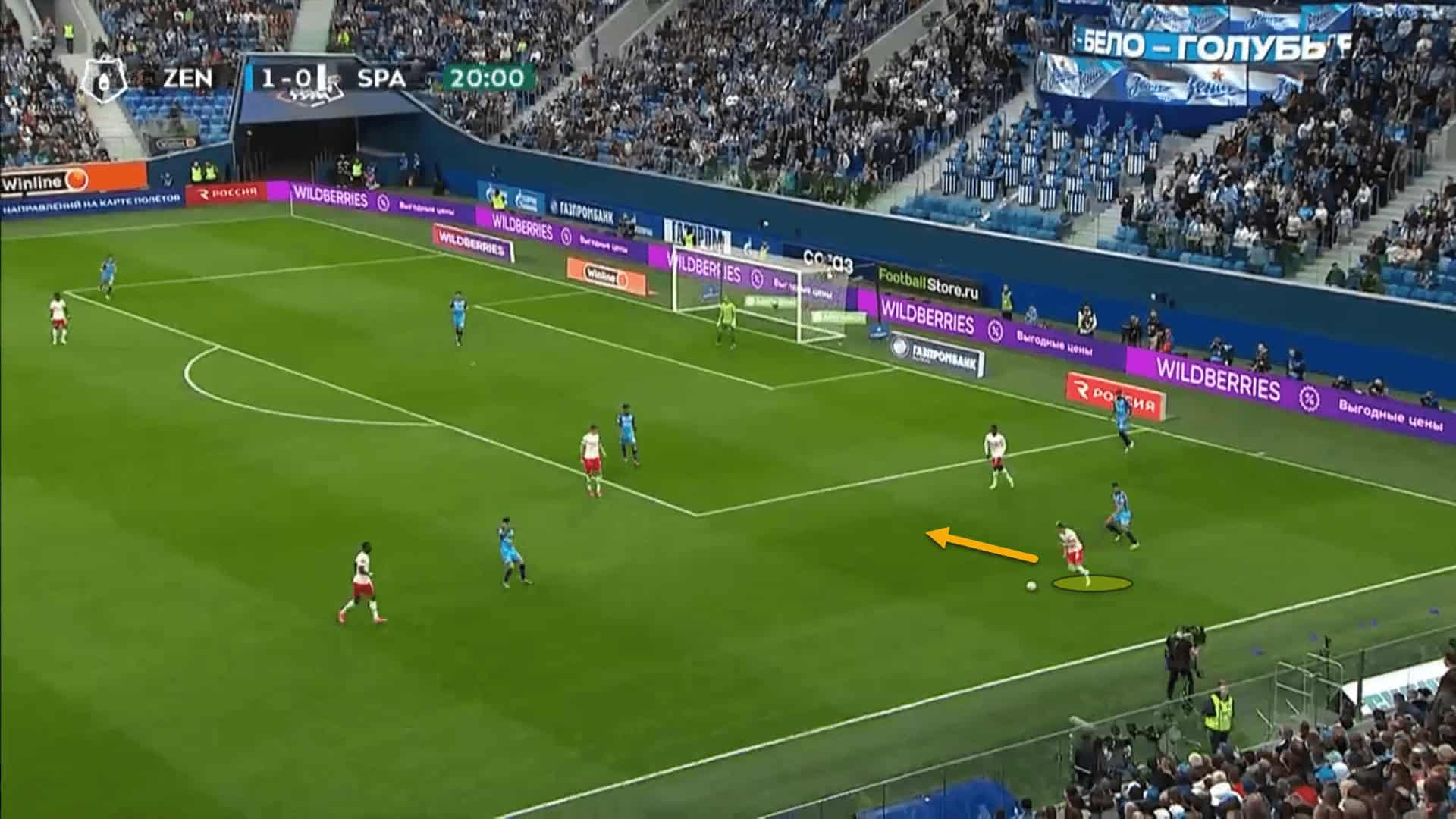

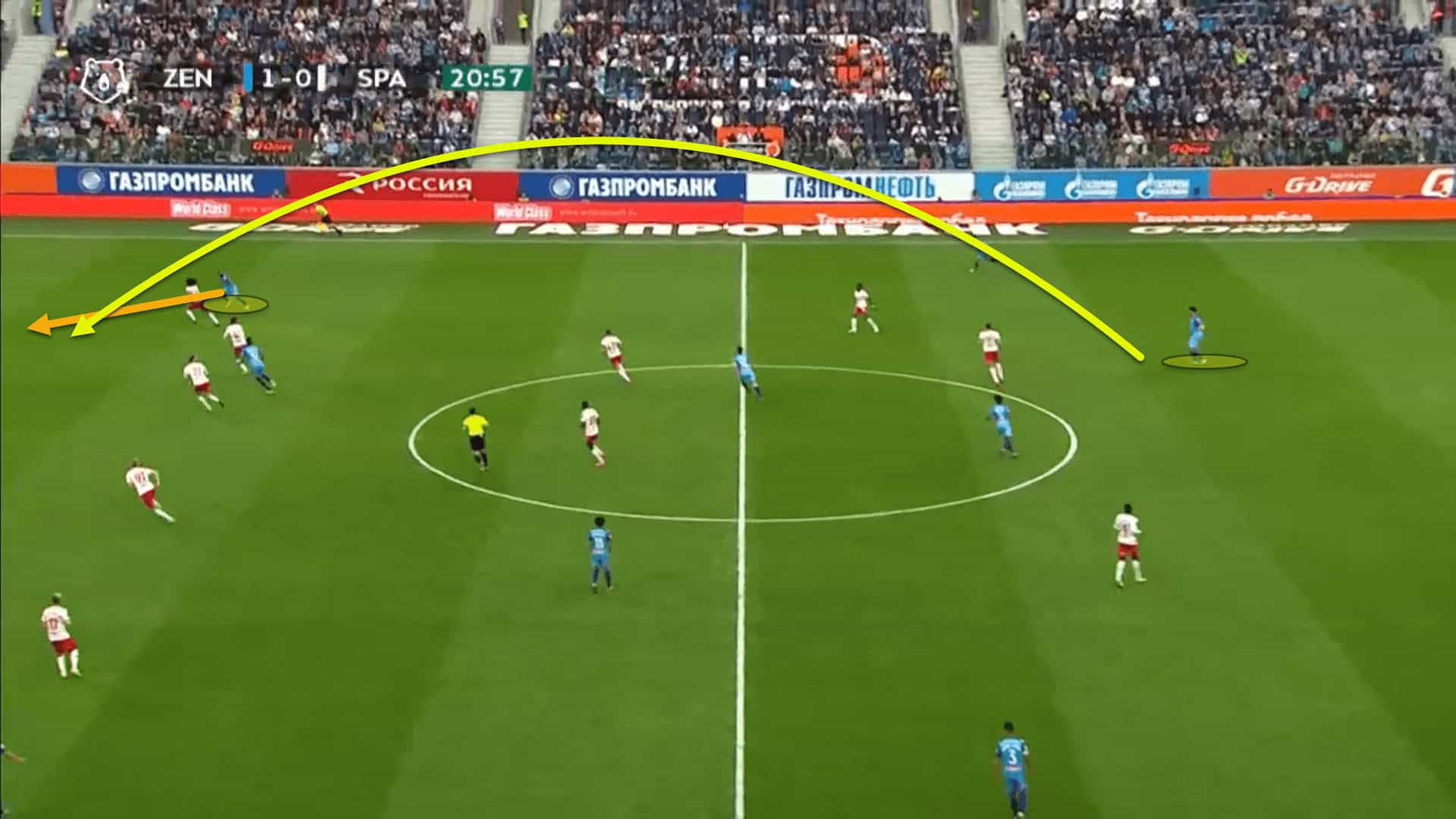

Nevertheless, we noticed that Zenit had some difficulty when playing out from the back in the wide areas against a man-oriented press.

Quite often, high-pressing sides will force the attacking team to one flank and will ‘lock on’, going man-for-man in the wide areas to force a turnover of possession.

As Zenit keep the wingers very high, they tend not to drop deep to support the build-up play which means that the fullback doesn’t have an easy angle down the line to play to when they are under pressure. Instead, only the pivot player, nearest central midfielder and closest centre-back are options to pass to.

However, as can be seen in the previous example, when the opponent has forced Zenit to the flanks and tightly marked the nearest passing options, their build-up struggles. In this instance, the only logical choice for the fullback Douglas Santos is to either try and dribble past his man, which is dangerous for obvious reasons or else to hook it long and hope the second ball can be won. The first option was Santos’ preferred route. Spartak regained possession and could have wreaked havoc.

Zenit are inventive and fluid in the build-up phase. While they may make life difficult for themselves, some risks are worth taking to entertain the supporters who watch on from the stands.

Functional play in the opposition’s half

Zenit blend the positional with the functional when breaking down a defensive block higher up the pitch. There are still some positional principles which are adhered to by the players but the manager also affords them freedom to be as creative and as interpretative of space as possible.

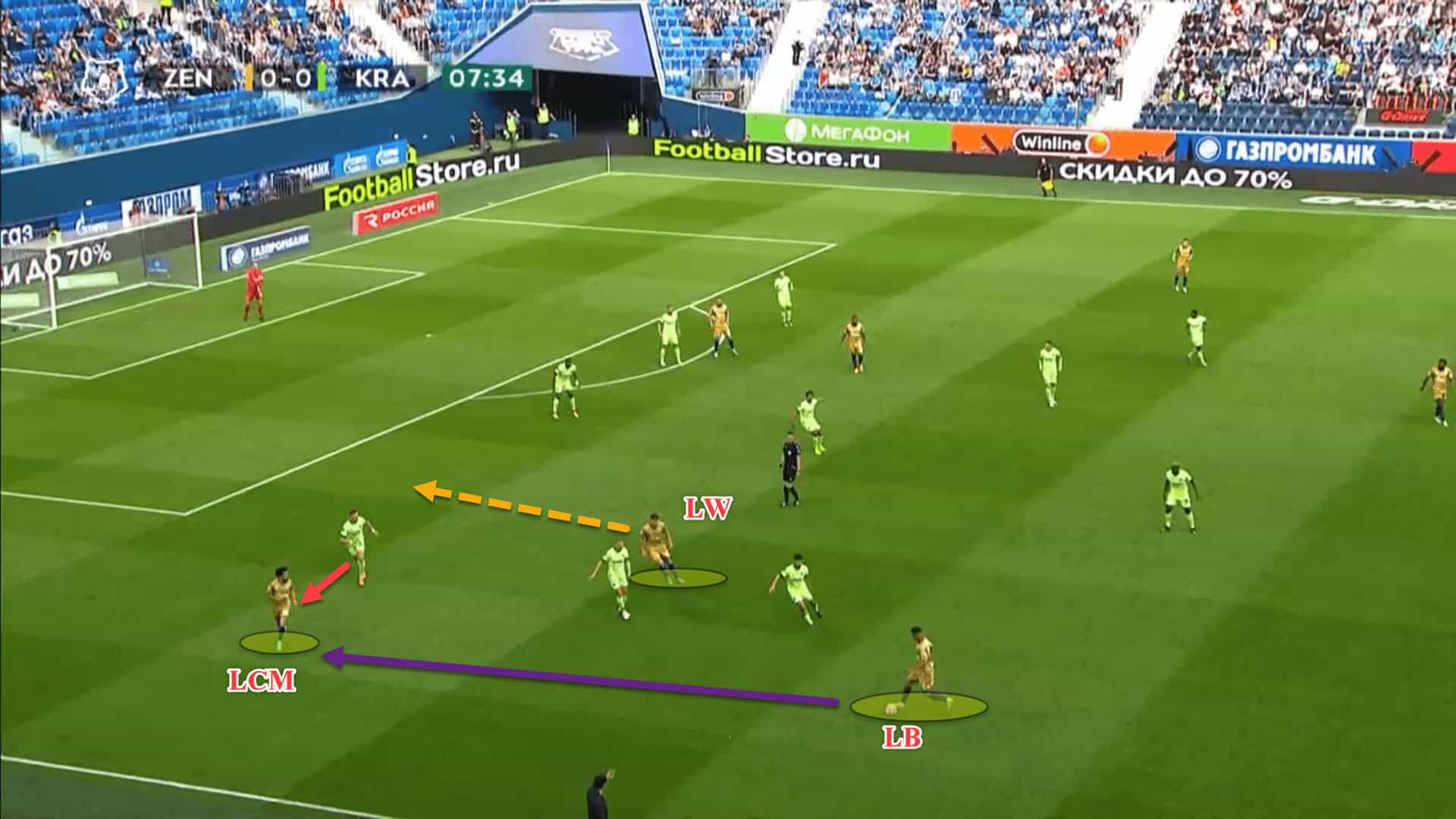

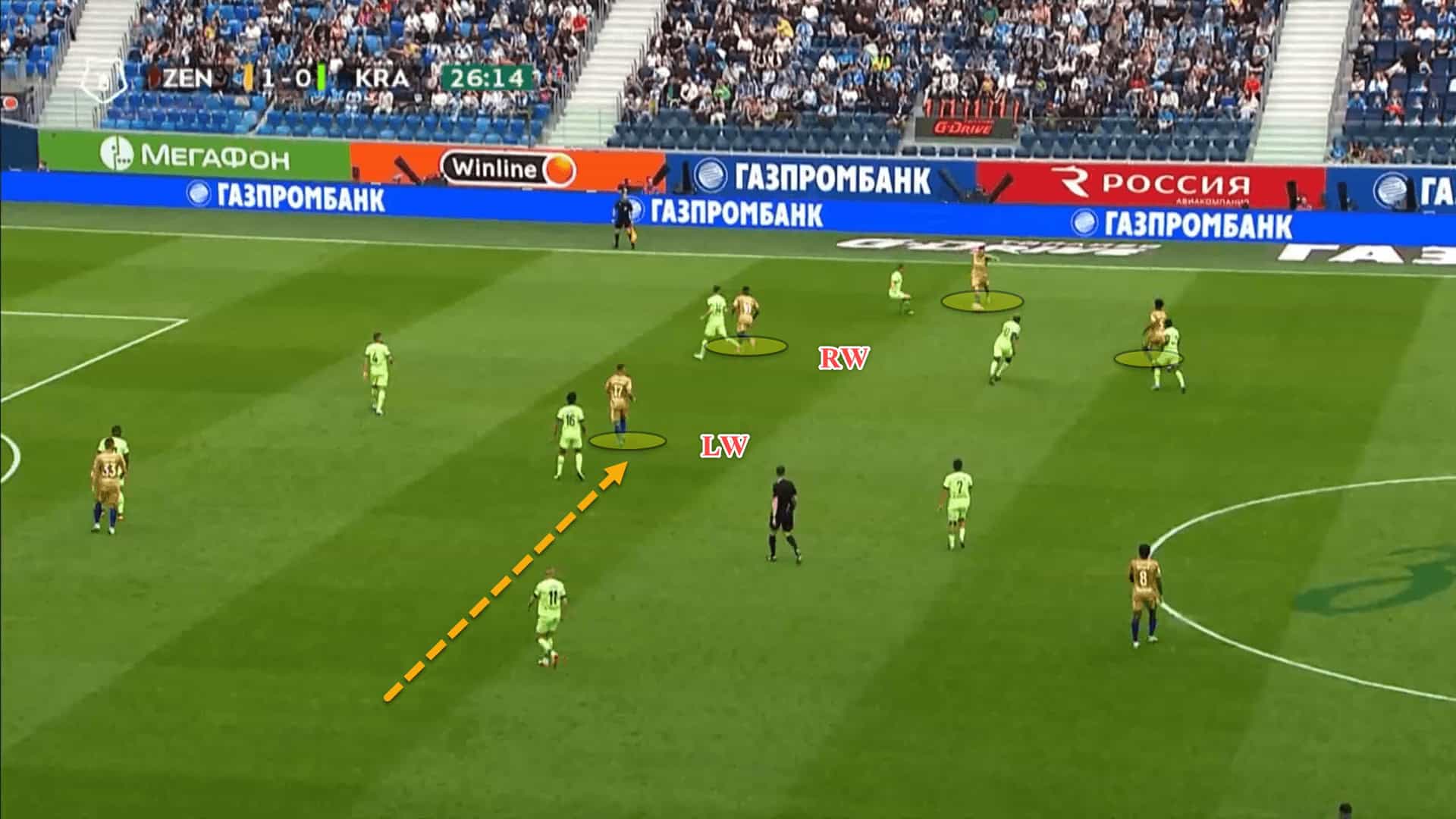

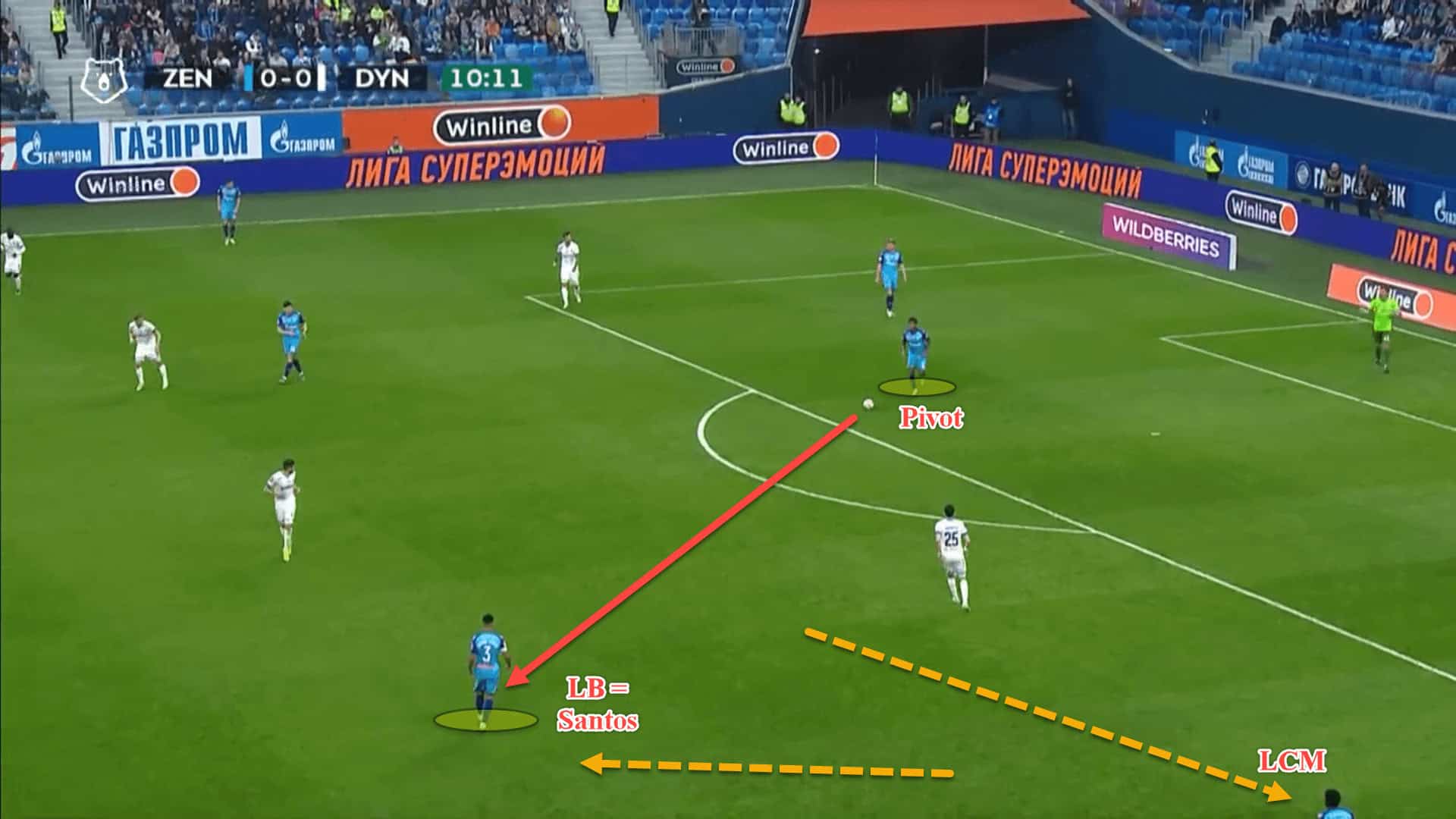

One of the prefixed principles imposed by Semak and his coaching staff is how Zenit’s players make halfspace runs in behind the opposition’s backline. This is done through the employment of wide triangles.

In the opposition’s half, these triangles primarily comprise the nearest winger, fullback and central midfielder. In the previous example, the left-winger was hugging the touchline, the left-back was sitting at the base of the triangle while the ball-near central midfielder was sitting in the halfspace.

The key to these triangles is constant rotation among the three in order to disorient the opposition’s backline.

Merely three seconds later, the composition of the triangle is different. Left-back Douglas Santos remains at the base but the left central midfielder, Claudinho, has moved out to the left flank while left-winger, Andrei Mostovoy, has pushed into the halfspace.

Claudinho’s movement has dragged the opposition’s right-back wider, opening the gap between Krasnodar’s fullback and centre-back. Noticing this, Mostovoy makes this common halfspace run in behind the backline on the blindside of the Krasnodar midfield and receives the ball after a flick from his Brazilian teammate.

From here, the opposition have one less defender in the box and Zenit can exploit this with an accurate cross.

Things don’t always need to be this manufactured, though. At times, when the defending team are sitting in a mid-block with a relatively high defensive line, it is perfectly common for Zenit to use the diagonal runs of their wingers in behind to try and get in on goal.

Players such as former Bordeaux and Barcelona man Malcolm as well as Mostovoy are crucial to this as Semak generally only deploys wingers who possess speed and can be a threat when attacking the depth and chasing balls over the top.

There are also functional elements to Zenit’s play, as has been referenced a few times in this scout report. Now, this doesn’t mean that Zenit play like Fernando Diniz’s Fluminense, but more so resemble Real Madrid or Napoli in the final third where players are given license to be more expressive as opposed to having a fixed position and being forced to cohere with set patterns of play.

For instance, here, Zenit have created an overload out on the right flank with both wingers on the same side of the pitch rather than having the two wingers fixed on their respective flanks. Mostovoy has came all the way across from the left to the right to join the overload.

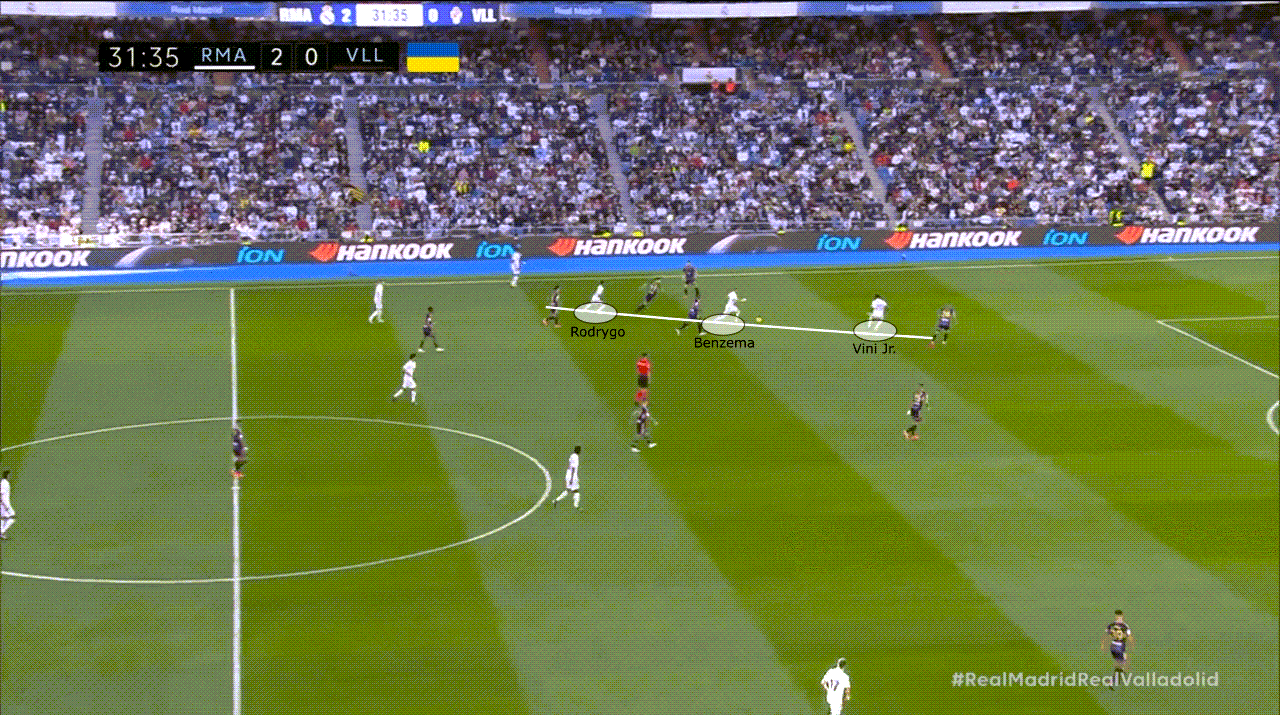

This is similar to Real Madrid under Carlo Ancelotti, particularly when both Rodrygo and Vinicius Jr. play in the same team.

Here, Rodrygo has come across to the left and has linked up with Karim Benzema and Vini Jr rather than holding his position on the right-hand side.

Since Zenit play with high fullbacks in the final third, it affords the wingers the ability to do this as there is no necessity for them to hold the width on each flank as the fullbacks are already doing so.

The objective of Zenit’s attacks is to get into decent crossing positions to put the ball into the box. When the ball is ready to be whipped in, the Russian giants pack the box with numerous bodies.

In this instance, Zenit have six players inside the penalty area and one just outside. Providing the cross is accurate, it means there is a higher chance that at least one player can tuck the chance away. However, there is also a higher probability that any rebounds fall to a Zenit player too given the number of players inside the box.

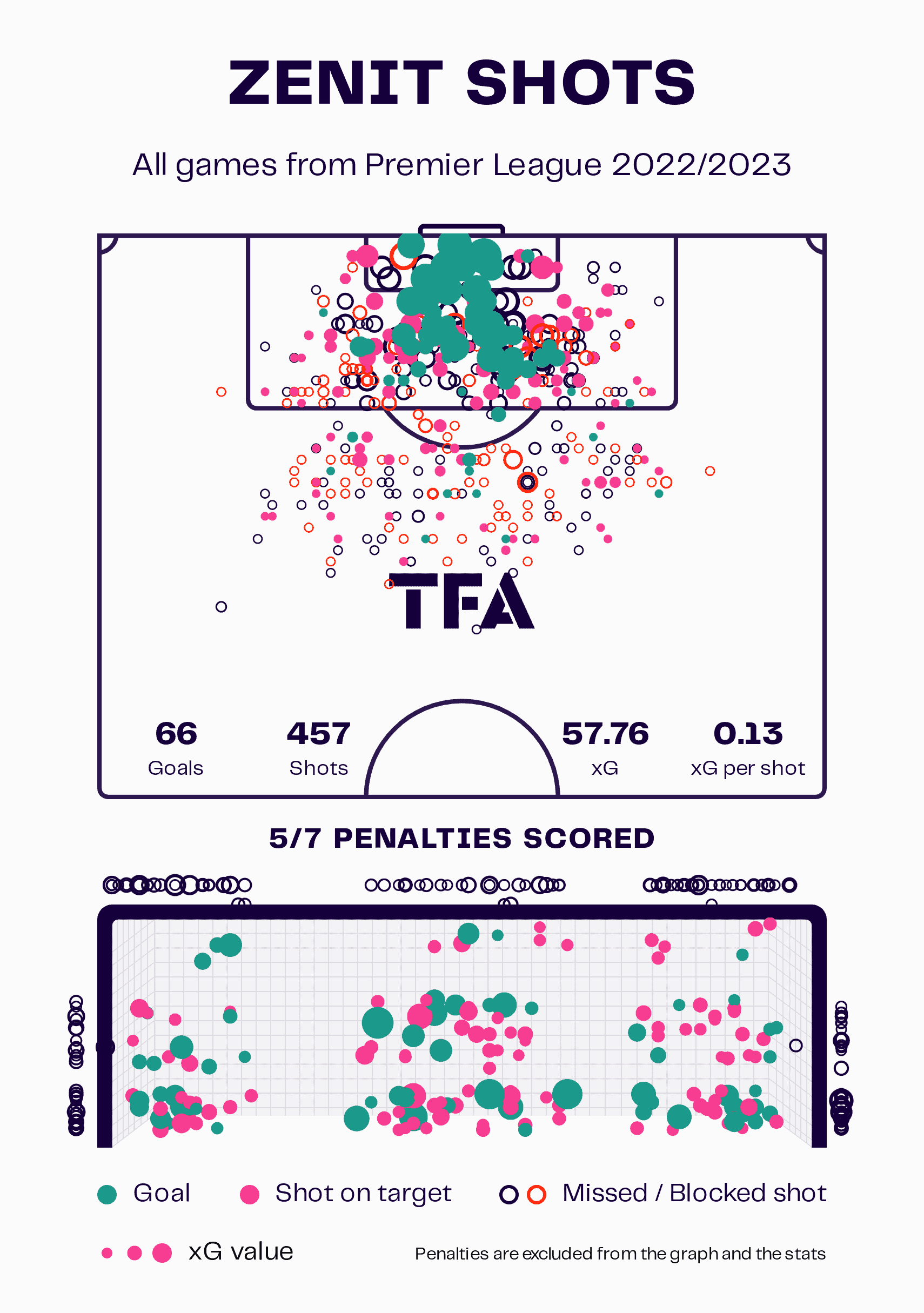

Zenit are excellent at finishing chances too. This season, Semak’s men boast the best attacking record in the Russian Premier League with 72 goals in total, including 5 from the penalty spot and one from an own goal.

This graph, which excludes the own goal, highlights just how good the champions have been in front of goal as Zenit are outperforming their non-penalty xG of 57.76, scoring 66 non-penalty goals.

With plenty of fluidity, rotations, functionality and potency in the attacking third, with added Brazilian flair all over the pitch, it can be easily argued that Zenit are the most exciting team to watch in Russia’s top-flight right now and have been for many years. Hence why it’s no surprise that The Zeniters have lifted the crown for five seasons on the trot.

Keys behind an excellent defensive record

If you thought that 72 goals scored in 28 games was impressive, wait until you find out that Zenit have conceded merely 19 goals in the same span of time. To break this down even further, Semak’s side are scoring 2.57 goals per game and conceding just 0.68 while currently maintaining a goal difference of +53 which is quite insane.

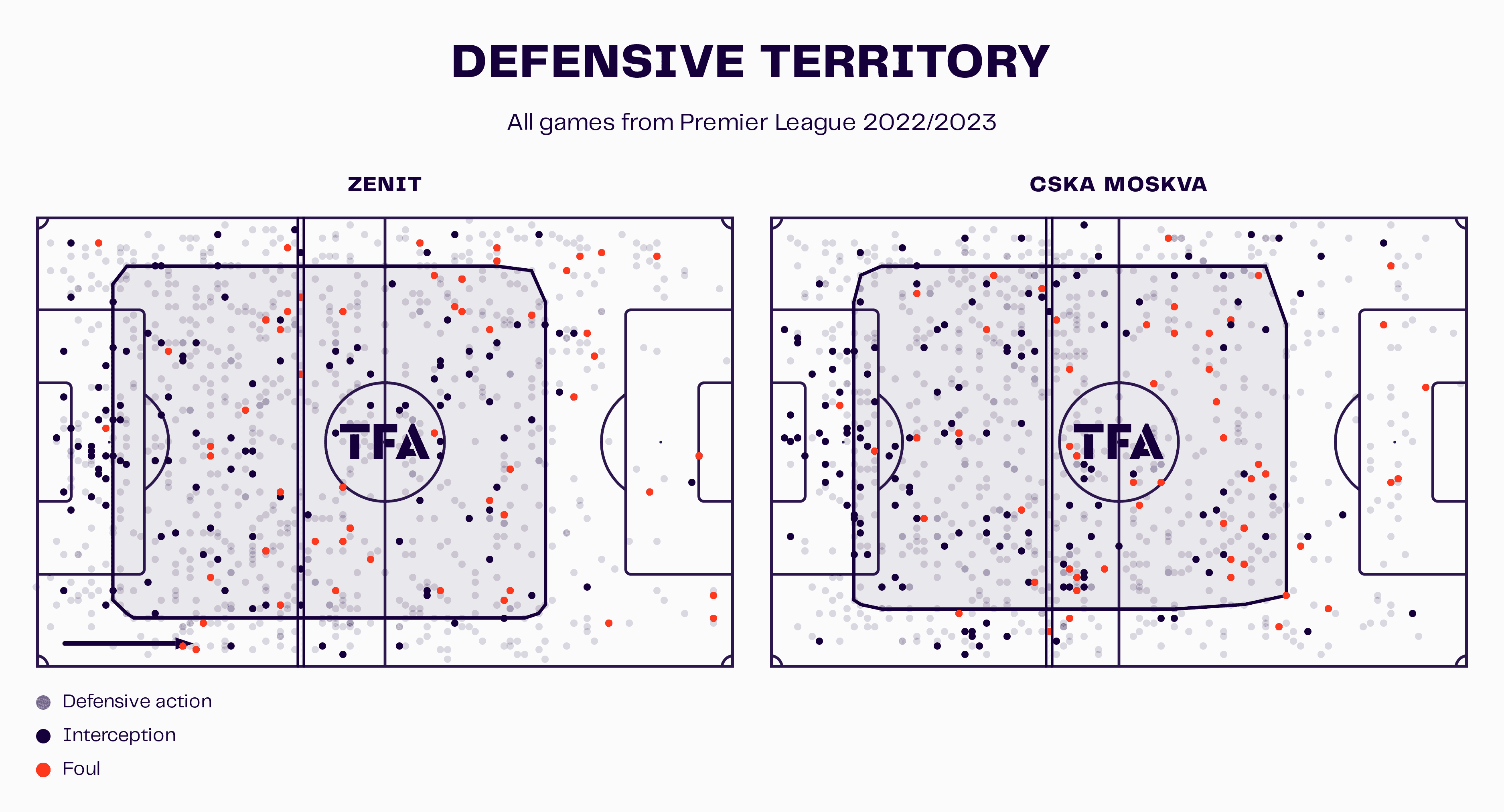

Zenit’s defensive record is also one of the best in Europe right now. But are Semak’s men sitting lower down the pitch to protect their own box or are they pressing high?

As we can see from this data viz, Zenit are pressing high up the pitch as the team’s average defensive line height is just below the centre circle. However, the defensive line still isn’t as high as CSKA Moscow who are second in the Russian top-flight right now.

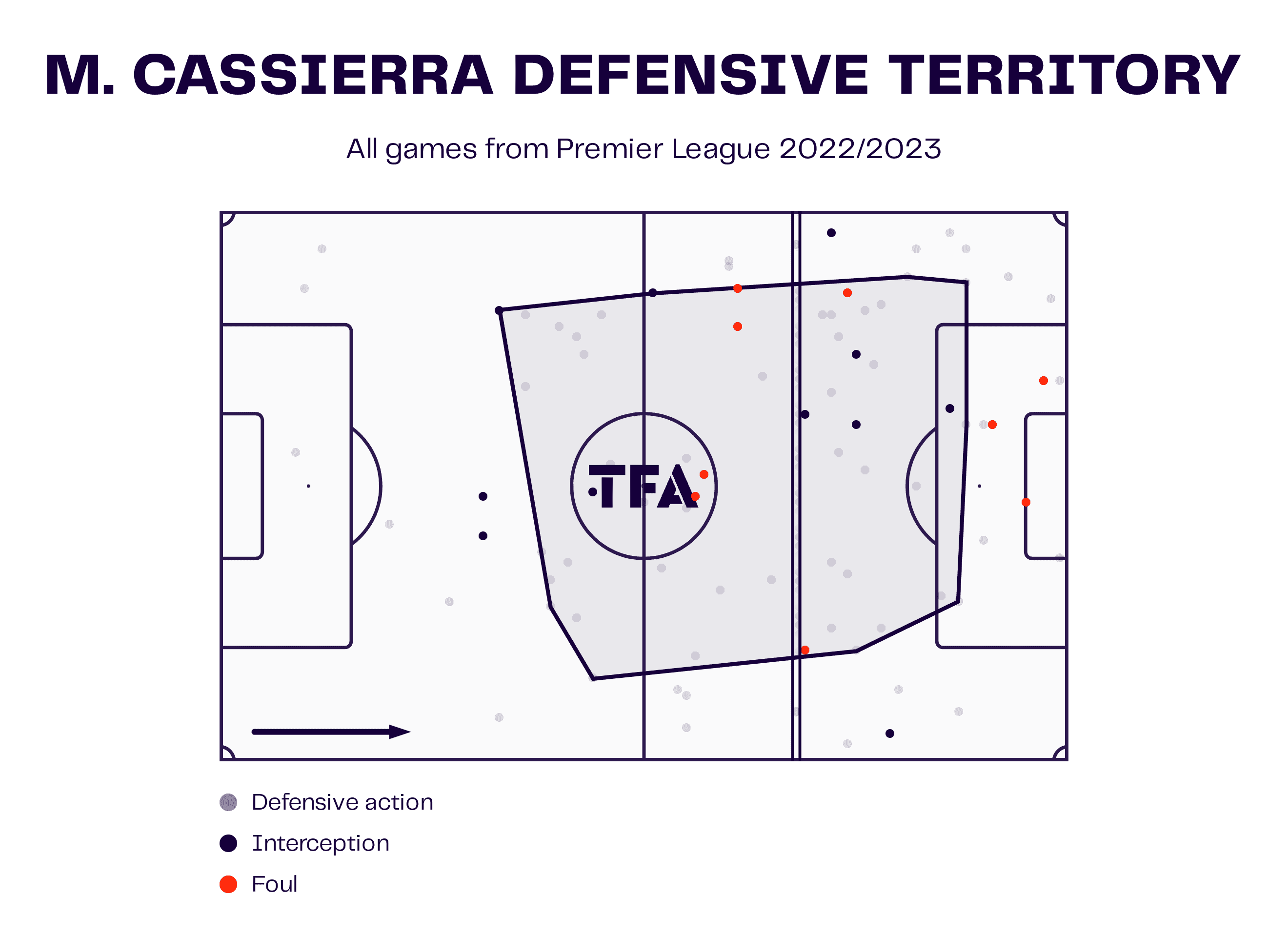

Zenit don’t intensely press like a lot of sides and are much more willing to sit in a mid-to-high block, waiting for a pressing trigger to bring the lines up. We can see this from the average defensive line height of Mateo Cassierra, a regular centre-forward in the Zenit set-up this season.

Cassierra’s defensive territory covers the middle and final third but stops just inside the opposition’s penalty area.

Nevertheless, the striker’s job isn’t to win the ball back, hence why so few ball recoveries can be seen on Cassierra’s defensive territory map. The role of the centre-forward in Semak’s system is to force the play to the wide areas, splitting the pitch for the opposition.

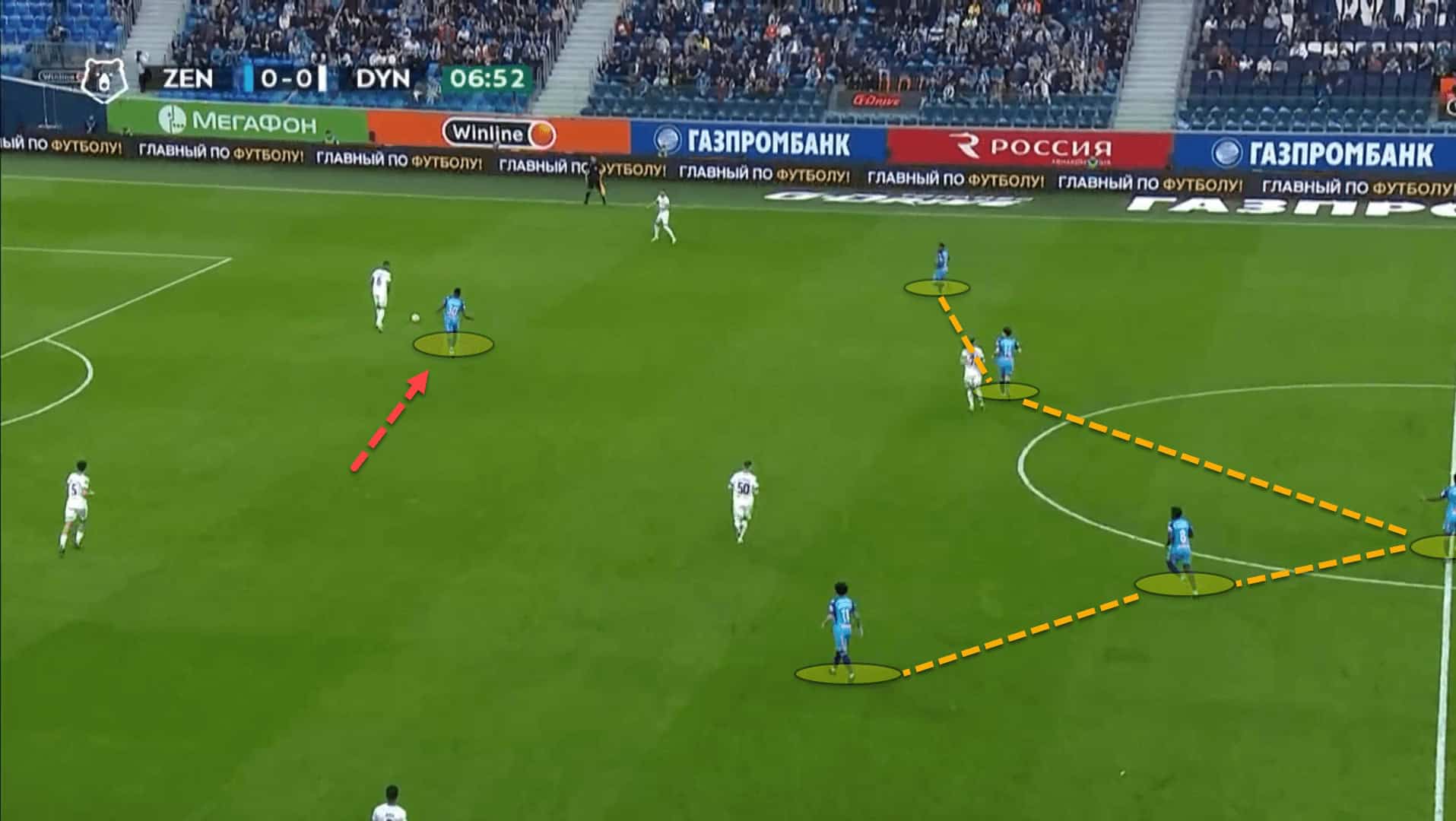

Here, Zenit’s number ‘9’ is pressing Dinamo’s left centre-back at an angle to block the passing lane off to his defensive partner. This forces the ball carrier to play out to the flanks to his nearest fullback instead of trying to circulate the ball around.

Once the ball is forced wide, the rest of the players go man-for-man on the flanks and press aggressively to win possession back as quickly as possible, using the touchline as an extra defender.

This nearest fullback is also involved in this. When the opposition’s nearest winger drops to create a passing lane down the line, Semak wants the closest wide defender to follow his man into a deeper area to ensure that there is no route of progression for the opposition to get out of the press, smothering the attacking side into submission.

To fill the void left by the fullback, the rest of the backline swing across to cover, creating a very narrow pressing shape, but one that may be susceptible to switches of play to the far side.

Semak wants to keep the opponent as far away from the Zenit goal as possible which has worked wonders this season.

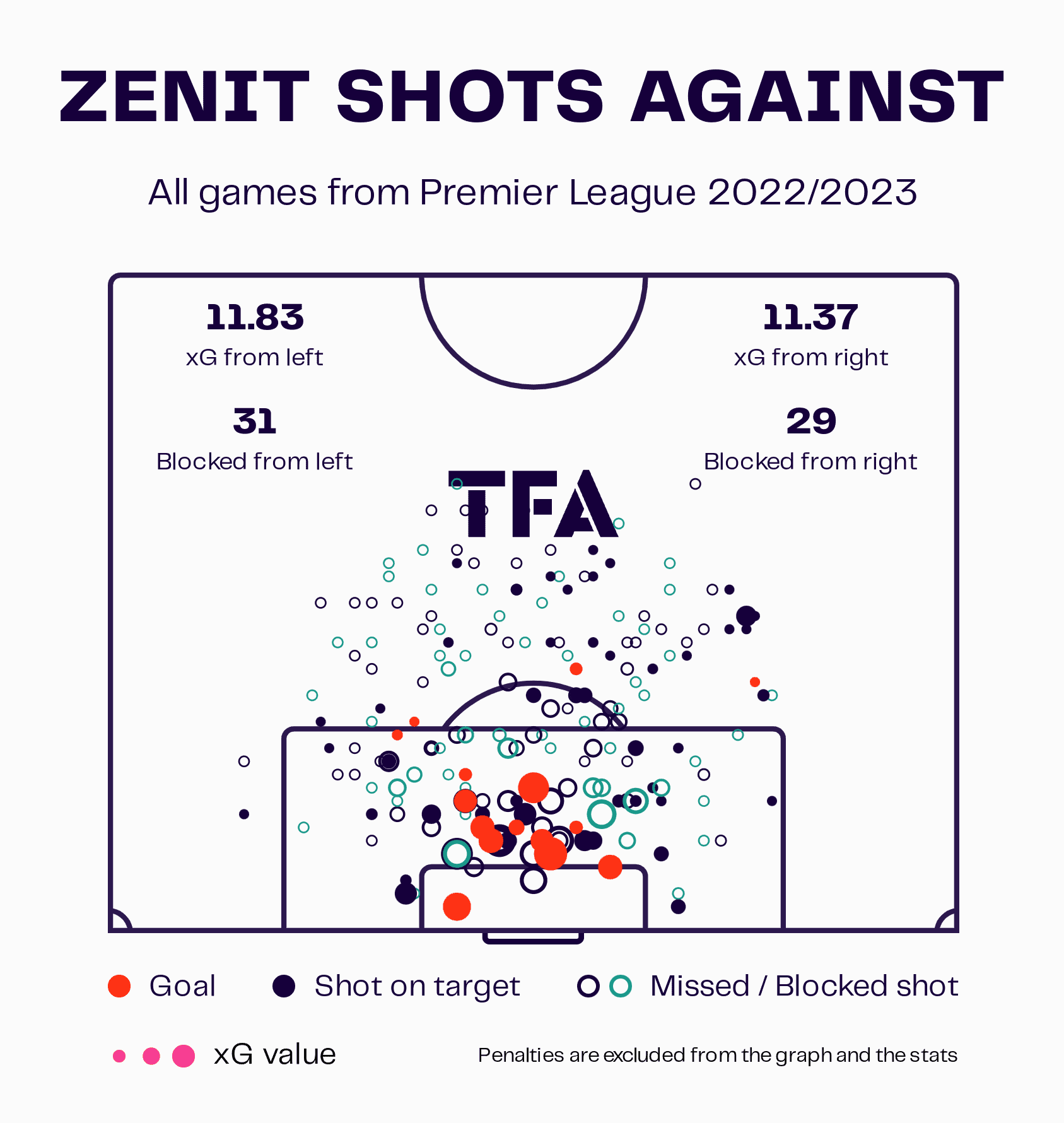

Zenit have conceded an xG of merely 23.2 in total in the league in 28 matches. This is a phenomenal record for the Russian side. They are outperforming this number too, having conceded 19 goals across the 28 games, although it’s just a slight outperformance.

But it shows how few chances Zenit are conceding on a game-to-game basis.

Conclusion

It is incredibly rare for a team to boast the best attack and best defence in a league without winning it. Thankfully, Zenit were no exception and managed to get the job done with plenty of time to spare.

Semak has managed to do the unthinkable with the St Petersburg-based club by guiding his side to five-straight Russian Premier League titles and it’s even more terrifying to think of how much more the manager can achieve.

Comments