Olympique de Marseille have not finished in the top three of Ligue 1 since 2012/13, but since then Paris Saint-Germain have established a monopoly, and have won the title six out of the past seven seasons. André Villas-Boas has a tough job on his hands if he is to restore France’s joint most successful club to their former glory. The Portuguese tactician has certainly impressed in his first season as Marseille manager. When the 2019/20 season was called off, Marseille were lying second, 12 points behind PSG and six points ahead of third-placed Stade Rennais. In this tactical analysis, I’ll explain the tactics Villas-Boas has used this season at Marseille using analysis.

Formations

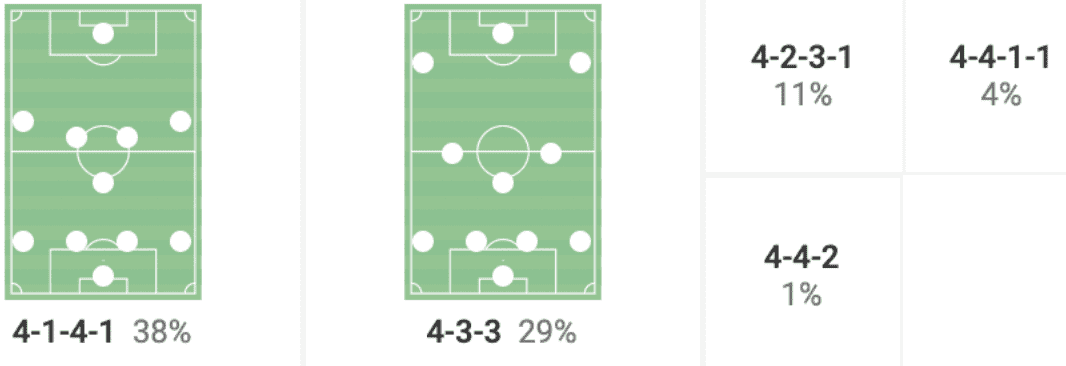

Villas-Boas has used a 4-3-3 or a similar variation (4-1-4-1) 67% of the time. When not using a 4-3-3, he has occasionally played a 4-2-3-1, or a similar variation (4-4-1-1), 15% of the time.

Villas-Boas has tended to pick a consistent starting team as much as possible, with his favoured selection this season being the following:

GK: Steve Mandanda

RB: Hiroki Sakai

CB: Duje Ćaleta-Car

CB: Boubacar Kamara

LB: Jordan Amavi

DM: Kevin Strootman

CM: Valentin Rongier

CM: Morgan Sanson

RW: Bouna Sarr

LW: Dimitri Payet

CF: Darío Benedetto

The most notable absentee from Marseille’s regular starting XI this season is Florian Thauvin, who has missed most of the season due to injury.

A key feature of Marseille’s squad is the versatility of their players, like Kamara who is often used as a centre-back, Sarr who has been used as a backup right-back, and Sakai who has the versatility to play left-back at times.

Prioritisation of width in attack

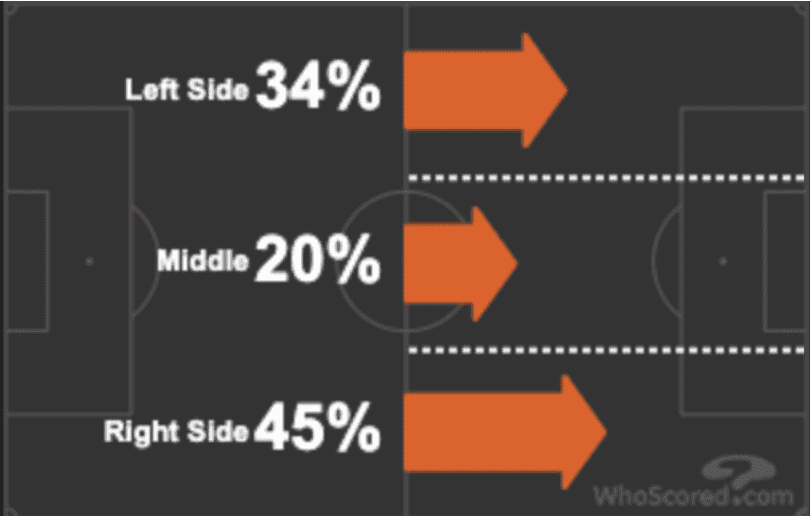

Marseille heavily favour attacking down the wings, with just 20% of Marseille’s attacks through the central channel, the lowest in Ligue 1.

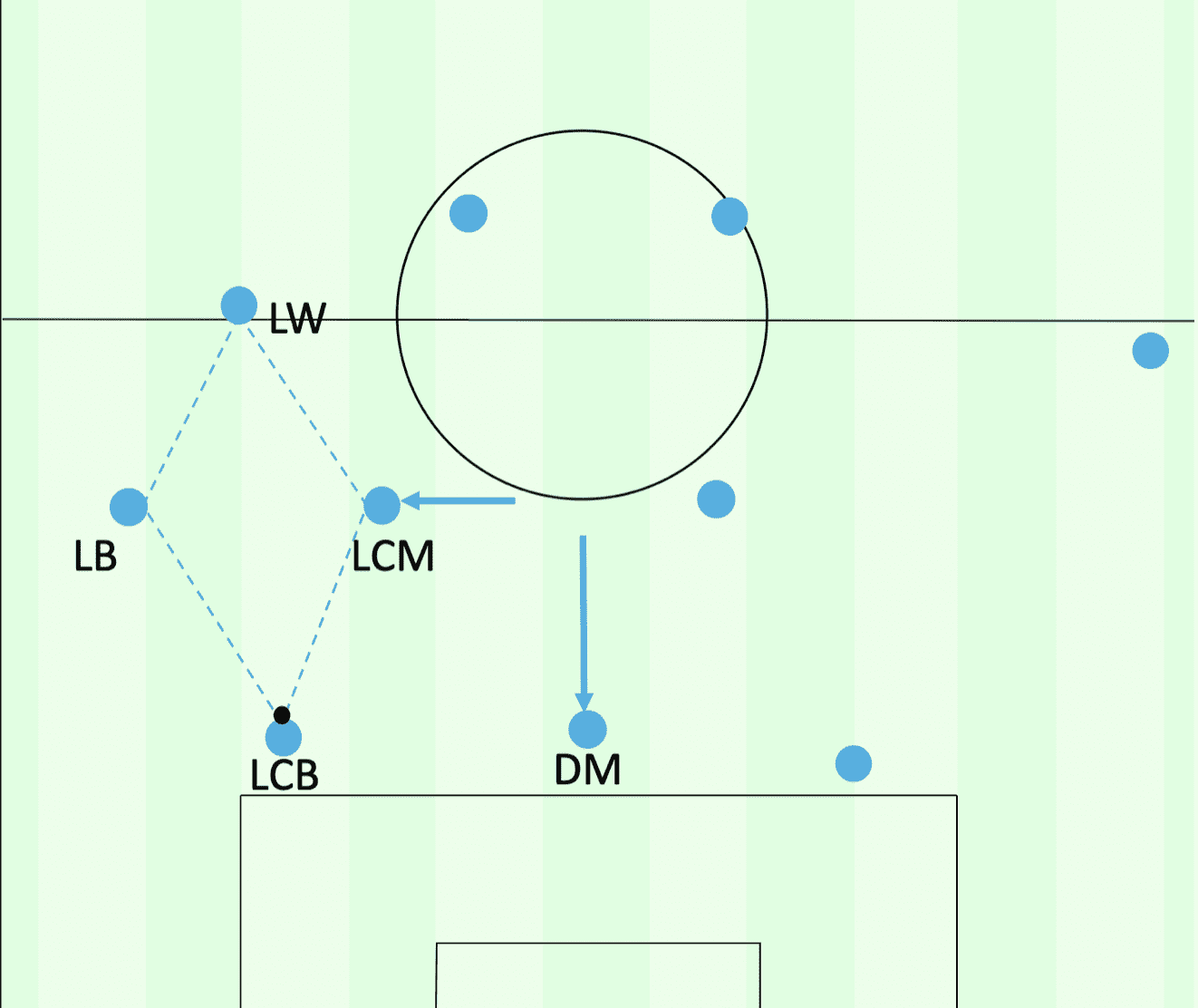

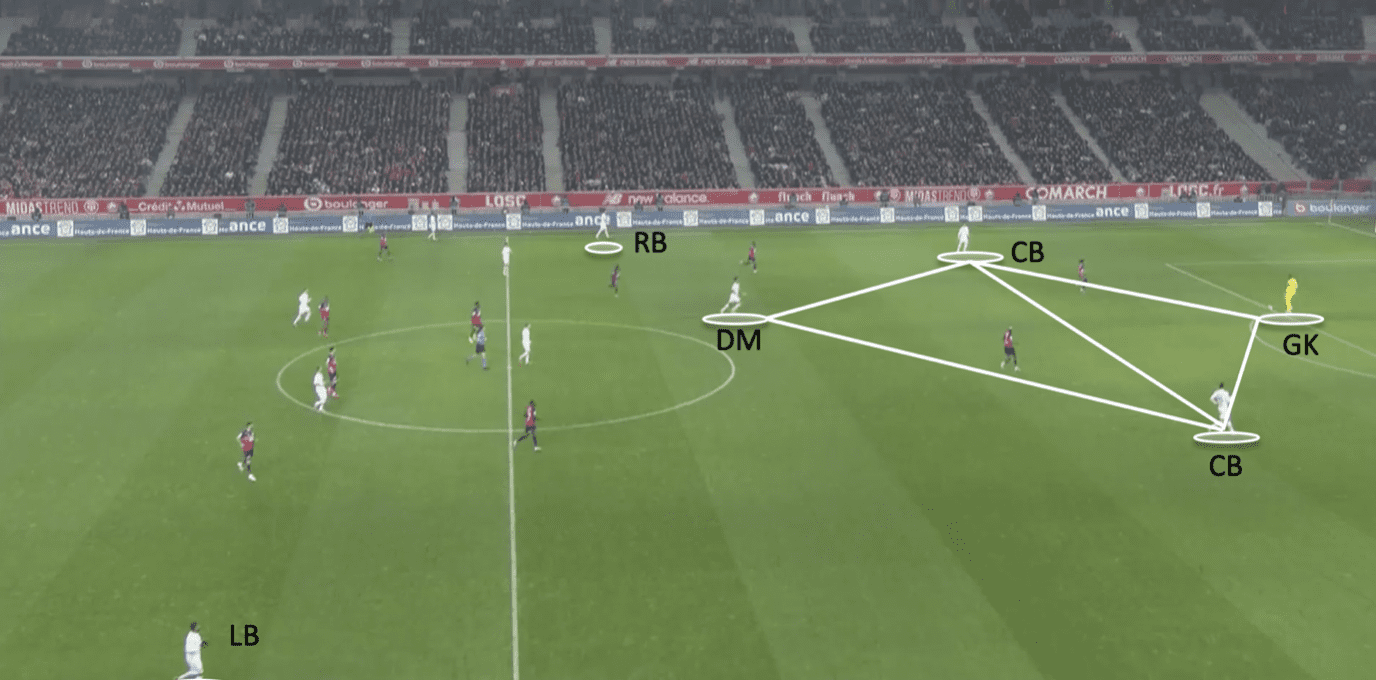

Attacking down the wings can mostly seem like a very one-dimensional offensive style, however, Marseille engineer intelligent dynamics when attacking, which make it difficult to defend, for the opponent. Marseille will look to create overloads in the wings and halfspaces. The defensive midfielder will either drop between the centre-backs or just ahead of them to create a triangle, and the centre-backs will then split wide. If the defensive midfielder has dropped between the centre-backs, the shape becomes a 3-4-3.

The nearside central midfielder will shift into the halfspace, while the nearside full-back will take up a more advanced position. This creates a diamond, with the centre-back and winger at the tips, while the full-back and midfielder occupy either side. This is shown in the diagram shown below. The left centre-back forms the base of the diamond, and the left central midfielder shifts into a wider position, in line with the left-back who has pushed higher. The left winger drops slightly to form the tip of the diamond, while the defensive midfielder drops in between the centre-backs.

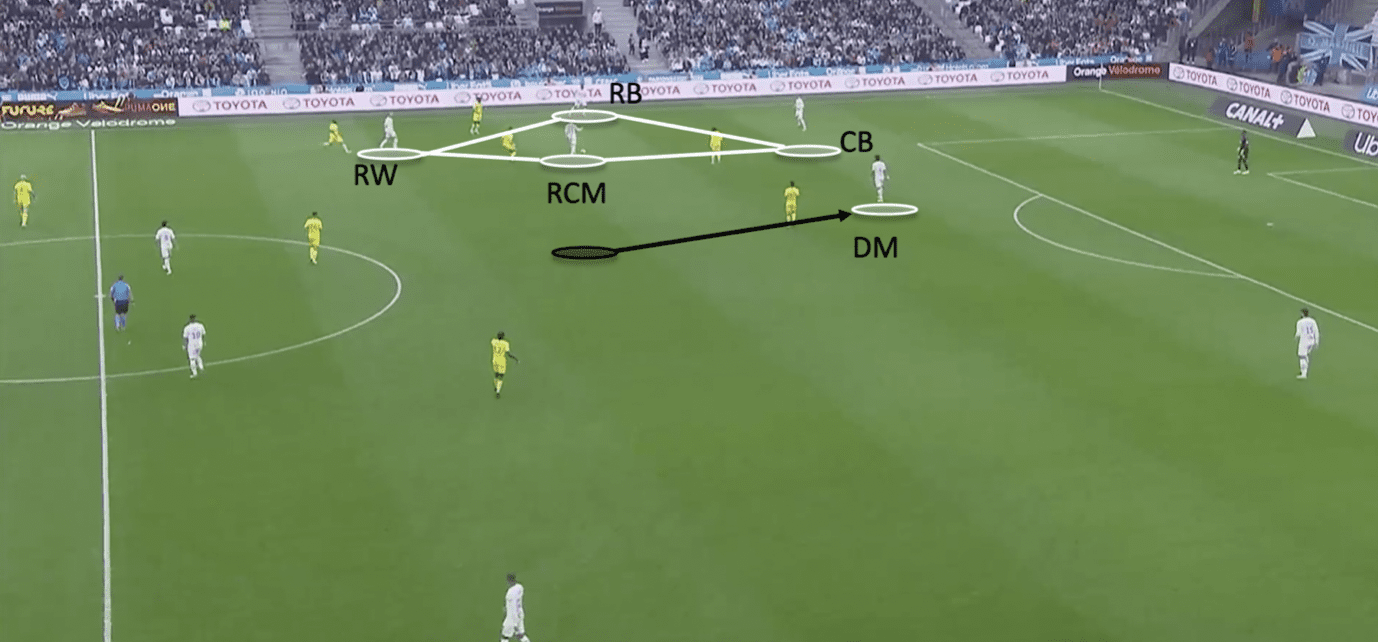

In the in-game example pictured below vs FC Nantes, this pattern occurs on the right side. The centre is almost completely unoccupied, while the far side full-back maintains a wide position.

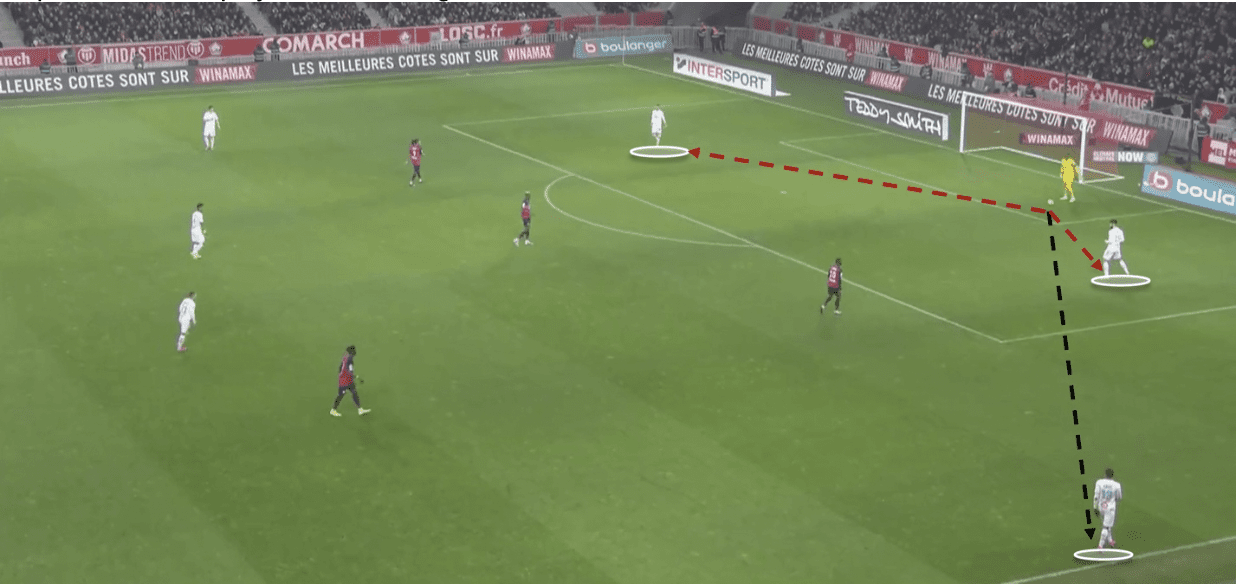

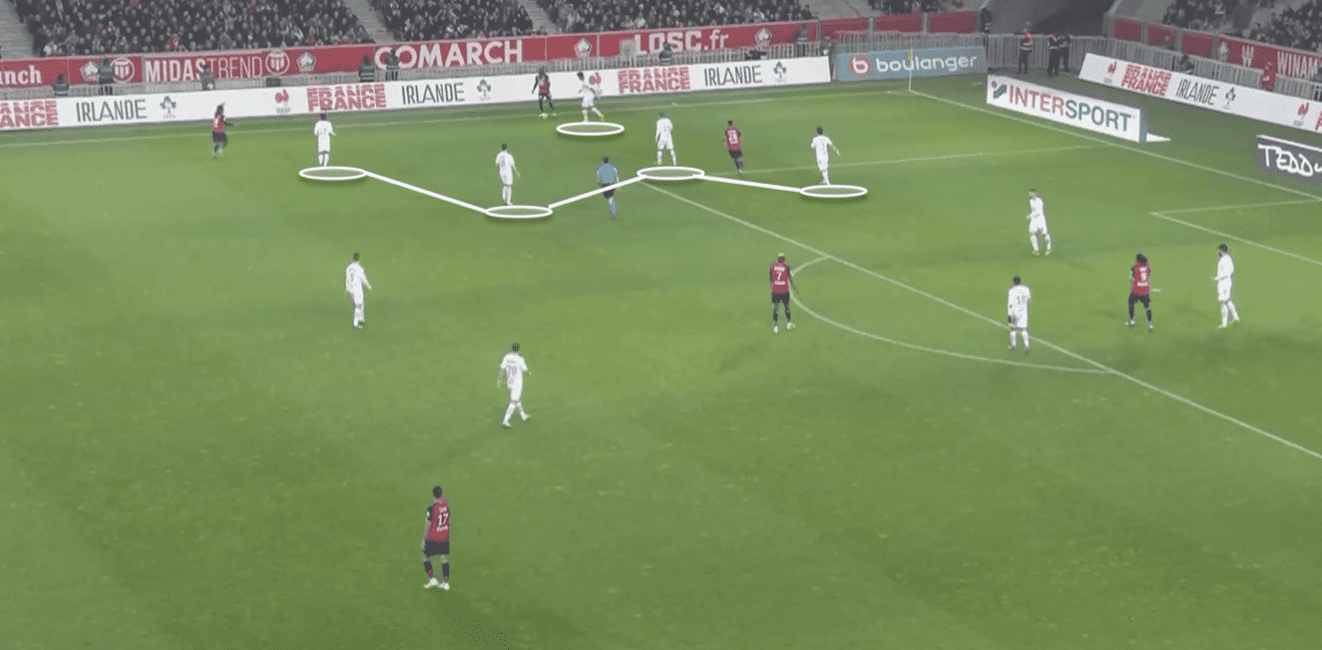

The image shown below is a perfect example of how Marseille prioritise playing to the wide areas as much as possible. There are two open short options from the goal kick, but Mandanda chooses the more difficult option: playing to the full-back. The two midfielders shown in the picture do not make an effort to make themselves available between the LOSC Lille pressing players, highlighting the heavy emphasis on wide play while attacking.

An important principle for Marseille is the utilisation of the full width of the pitch. Even when the ball is on one wing, the far side full-back will maintain the width. This often presents opportunities for switches of play. In the example shown below, we can see both full-backs occupying opposite wings to stretch the play. We also see the defensive midfielder creating a triangle with the centre-backs, or a diamond when considering the goalkeeper.

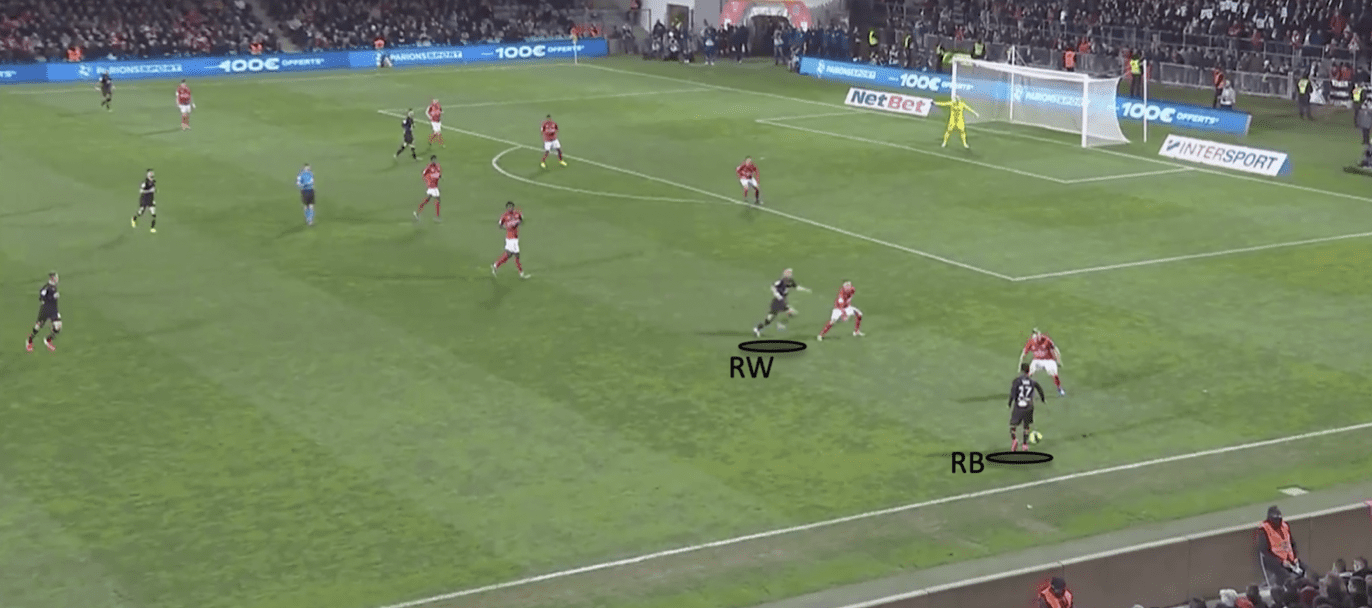

The primary method of chance creation for Marseille is crosses, with them averaging 13 crosses per 90 minutes this season. Both overlapping and underlapping runs are used to overload the wings and engineer space for a cross. In the first example, the right-back underlaps the right winger.

The dynamic of having one player positioned in the half-space while the other is on the wing is used often while attacking, and the full-backs and wingers are almost never found on the same vertical line. The next example shows the inverse of this, with right winger in the half-space and left-back positioned on the wing.

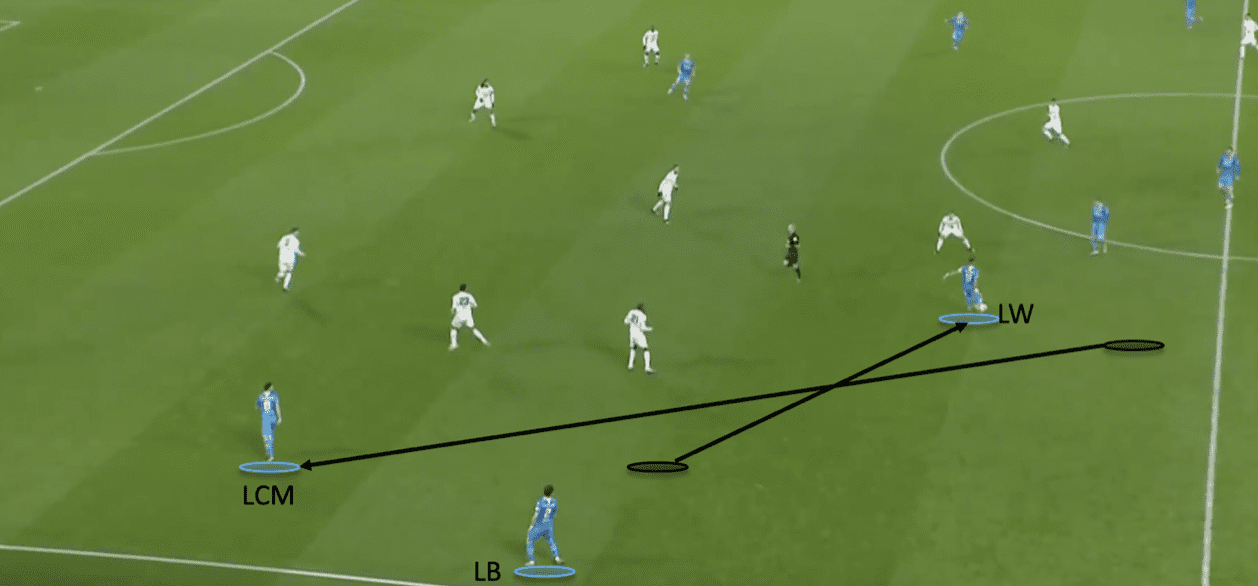

Another method used to overload the wing is the use of a central midfielder making a diagonal run from the centre to a wider position. As shown in the image below, the left central midfielder has made a diagonal run from in to out, creating space for the left winger to drive into and switch play.

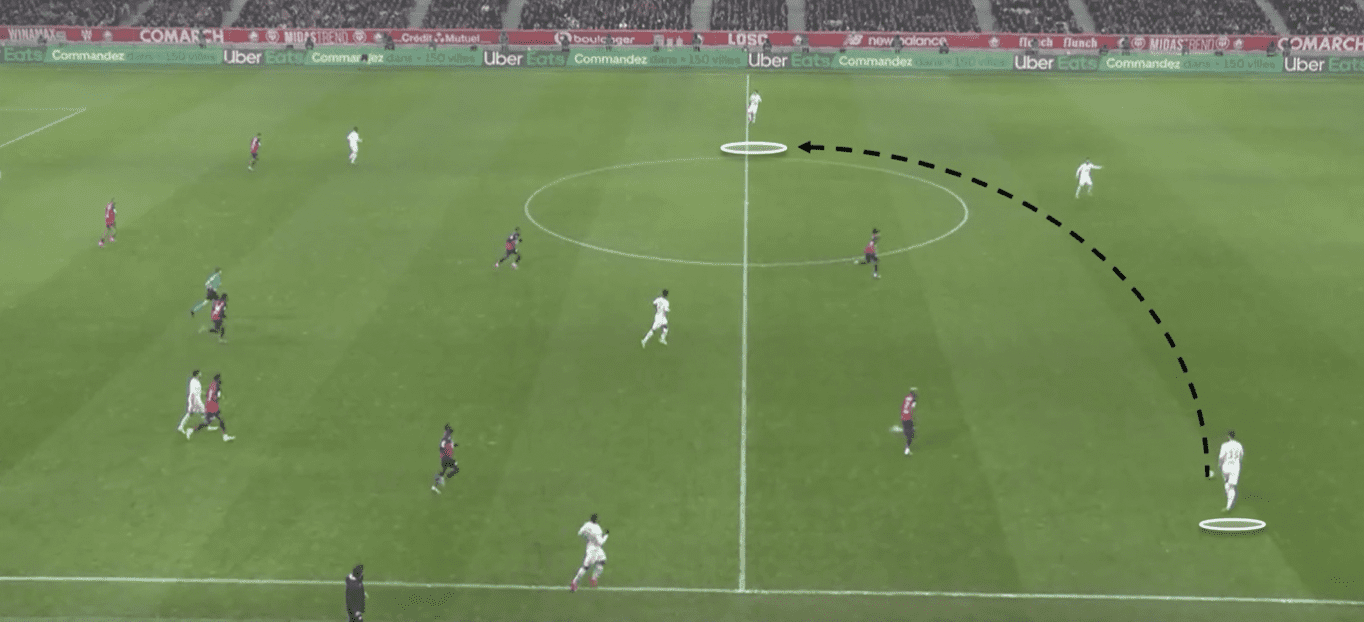

Marseille are direct, and players will prioritise the furthest pass possible, especially when the option is a wide player. As we can see in the example shown below, Ćaleta-Car has an easy pass available, but he chooses the longer switch into space, which is available due to the full-back staying wide.

Here we can see an example of the wide diamond once again. However the right centre-back chooses the most direct option and plays to the right winger, even though the right central midfielder and right-back are safer, less risky passes.

Despite being a very direct and vertical team, Marseille do not rely on long balls to progress possession, rather utilising a multitude of short and medium passes to quickly advance play. Marseille’s average pass length this season is 19 meters.

Forcing the opponent to the centre when defending

When the opposing team has controlled possession of the ball, Marseille fall into a 4-1-4-1 mid/high block. When in this shape, the team is mostly passive until the ball leaves the central areas. Marseille are particularly passive when the ball is in the centre, often leaving large gaps in midfield for the opponent’s midfielders to receive the ball, in front of the block. When the opposing team creates a situation where they can utilise width, Marseille shift their defensive shape across, cutting out passing lanes to players in the half-spaces and wings. They leave the opposing central players open in order to coax the opponents into playing to the centre. As seen in the image shown below, Marseille (blue) cut out the wide and half-space passing options while leaving a large space in the centre for the opponents to play into.

Marseille will press aggressively when the ball is near the flanks, looking to suffocate the ball carrier with numbers and push them up against the touchline. As seen in the image shown below, Marseille create a “cage” around the ball carrier cutting out all of his passing options, while one player applies pressure. Marseille’s PPDA (passes per defensive action) is 10.25 this season, the third highest in Ligue 1.

We can see another example of this intense pressure against the touchline in Marseille’s win over Nîmes.

Usage of switches in player’s position to create preferable shapes

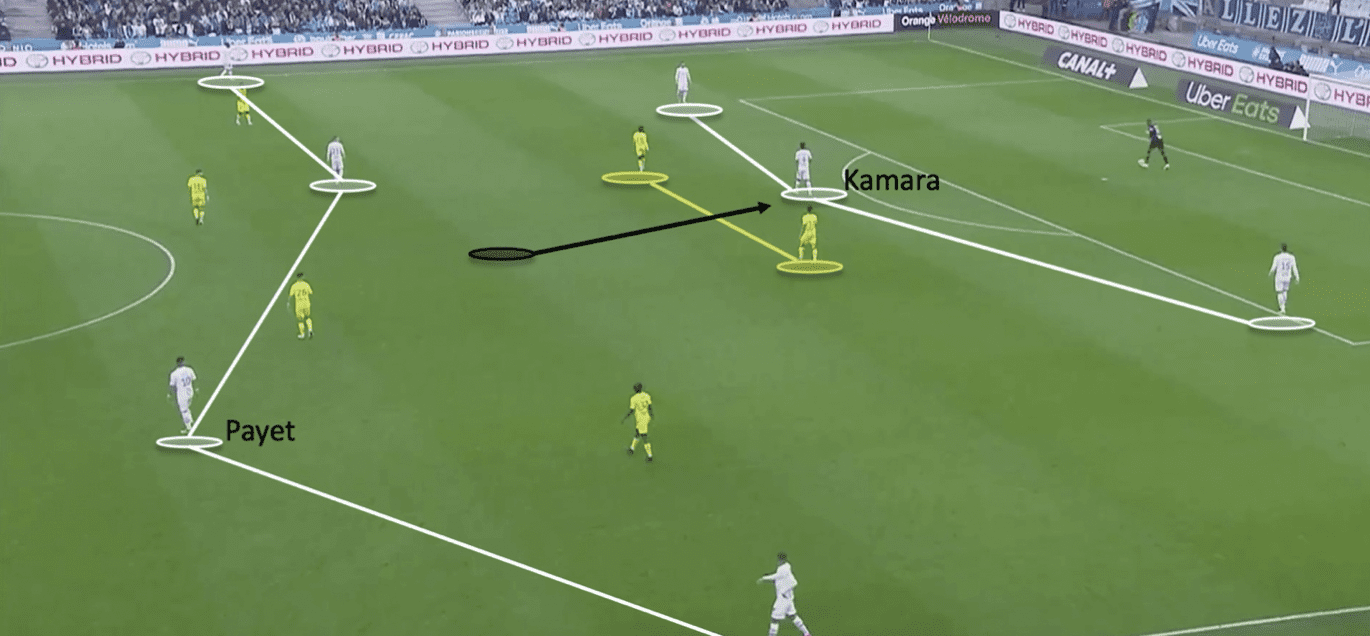

Marseille often switch the positions of their players on the fly, to ensure that consistent shapes are created. As mentioned previously, the defensive midfielder will often drop in between the centre-backs. This usually occurs when Marseille are facing a press of two centre forwards, to create a 3v2 numerical superiority, or when one of the wide centre-backs needs to cover a particularly large distance to form the base of the diamond. Marseille tend to create the same shapes as often as possible. In the example below, we can see the defensive midfielder (Kamara) drop between the centre-backs. Payet has taken up the position of left central midfielder, to occupy the space vacated by the current left central midfielder who was out of position.

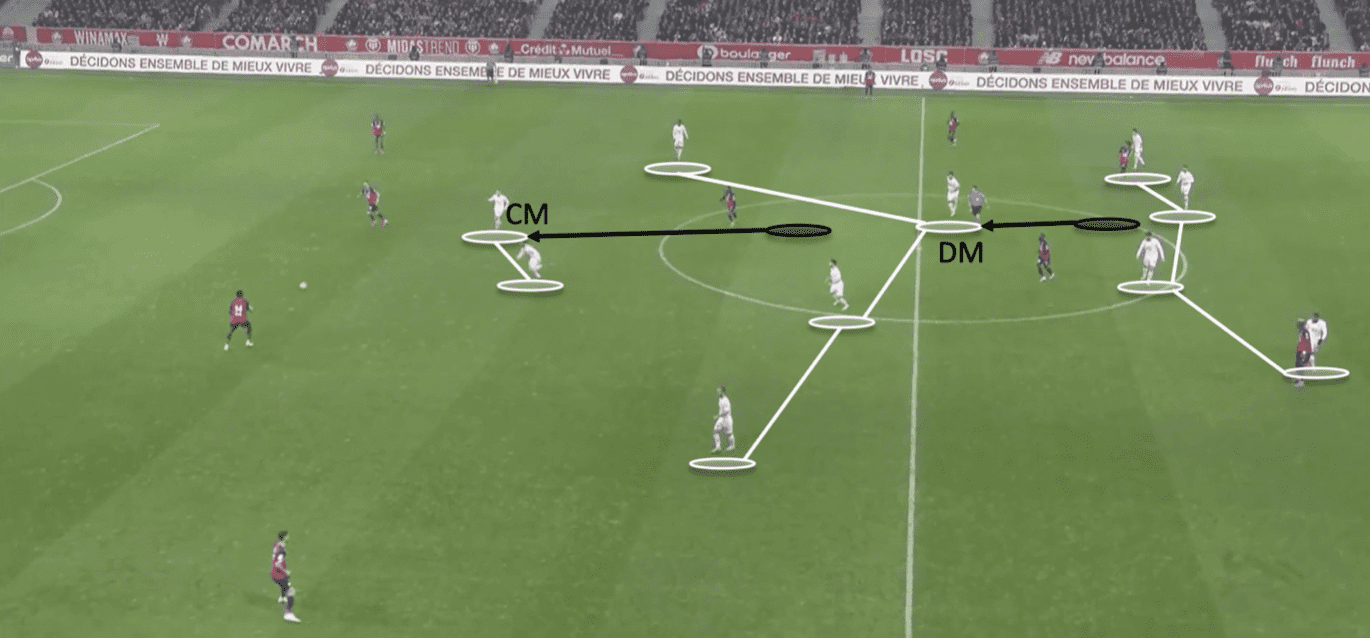

Another common case of switches in players position comes when Marseille are in their 4-1-4-1 defensive shape. When the opponent circulates the ball to one of their centre-backs, a Marseille midfielder (usually the right sided central midfielder) will step out to press, while the ball is in motion and join the same line as the striker to meet the receiving opponent, as he receives the ball. To ensure that a large gap does not form, the defensive midfielder will push up to occupy the vacated space. In the example pictured below, the midfielder steps out to press as soon as the pressing trigger of a pass to a centre-back occurs, the defensive midfielder steps forward to recreate the line of four, creating a 4-4-2.

Conclusion

After mostly disappointing spells in the Premier League with Chelsea and Tottenham Hotspur, followed by stints in Russia and China, André Villas-Boas is back in the limelight of one of Europe’s biggest leagues and is performing well when evaluating Marseille’s recent performances in the league. He has employed a clear tactical system which has Marseille competing at the top of Ligue 1 and has earned them UEFA Champions League qualification for the first time in seven years.

Comments