It’s about achieving goals.

Sports, especially Football, can be divided into two primary ideas — the goal and the way.

The way or approach has changed over the decades and varied according to desires.

“A goal without a plan is just a wish.” — Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Over the last decade, the teams have tended to increase the pressure, most notably the high-pressing and the attempt to regain the ball higher on the pitch, thus the popular tactics put more emphasis on building from the back instead of playing long.

People have focused more on the philosophies of positional and functional Play.

Accordingly, the long ball approach has been considered largely old-fashioned and a secondary playing style.

It makes some sense because the long-ball approaches typically have a small success rate, not to mention the possibility of having the appropriate tools for the execution.

Yet some maintain this more archaic type of play and choose the players based on it.

At the same time, others intend to operate it at the top levels in a very modern way.

Certainly, Brentford with Thomas Frank are among the best teams across the world routinely using the long ball approach remarkably with its different types, from set-pieces and open-play.

This tactical analysis piece will be an analysis of the pragmatism, tactics and types of long balls, and positional and qualitative superiorities.

The case study would be Brentford FC ’s open-play long balls and long kicks from their half.

Pragmatism’s short clarification

Generally speaking, pragmatism can be explained as a practical approach that prioritizes usefulness over theory.

“Pragmatism is the philosophy of action, not theory.” — US philosopher John Dewey

The pragmatic approach in football historically refers to practicality and effectiveness over flair and entertainment, achieving goals with a more direct style, rather than pushing to play attractive football — accordingly, the long ball approach can be considered a pragmatic style of football, which prioritizes directness and efficiency, aiming to exploit the opponent’s weaknesses by quickly moving the ball forward.

In contrast, several years ago, the mass taste in football shifted towards believing in the possession styles and the approach yet recently that has turned gradually to trying to integrate adherence to style and effectiveness.

This is a real impact of pragmatism on modern football, balancing X-axis, Y-axis and tempo.

Well, between this and this, after statistics and data invaded football, a modern pragmatic school emerged that selectively chooses suitable players to effectively implement a certain system to control the game with a different method.

Here, Brentford with Rasmus Ankersen are pioneers of an inspiring narrative for many teams today, we can say that this is part of modern pragmatism in football.

The belief that pragmatism in football is solely focused on defensive organization and pushing on speedy counter-attacks becomes traditional.

Rather, it has evolved to include the recruitment of low-priced players with specific attributes and training them effectively in the execution of long balls, set pieces routines and various kinds of defending styles like high-pressing schemes — Brentford are a true-to-life model.

“I like flexibility, I think the best teams have more weapons.

When needed, we can go longer — and that’s very difficult to defend.” — Thomas Frank

Static

“The long ball strategy can be effective if executed correctly, but it’s important to have a balance and not rely solely on it.” — Jose Mourinho

The first kind of long balls could be static ones, mostly from goal kicks, in which the ball can’t be pressed, and the play is paused for seconds which makes the long ball more accurate compared to open-play long balls while both teams are usually in a compact shape.

Open-play long balls or dynamic ones are characterized by creating chaotic and disorganized situations, in contrast, the pre-determined action of play makes the second-ball structure more organised like set pieces, and the opposition also exists in a pre-determined form.

The proximity of players in a pre-determined area creates consecutive aerial and ground duels to try to control play, this can be a form of qualitative superiority that can be exploited if you prepare more profitable players in some aspects like headers and physical players into the pressure zones against more vulnerable opponents are likely to have an advantage.

Teams usually position themselves vertically in three zones, for example, if the aim is to play the ball to the left half-space, usually they settle the width from the left wing to the central area.

Naturally, to have an effective manner of this type of long balls it is better to retain a goalkeeper who can play accurately, a target striker who can dominate aerial duels and flick on headers, fast players who can run onto loose balls and create chances and aggressive pressers who can win the second balls — Brentford have superior and influential players here to execute this form as Ivan Toney, Bryan Mbeumo, Mathias Jensen, Vitaly Janelt, and David Raya (who averaged 50.9 yards lengths of goal kicks with 85% per cent, according to Opta, with 7.66 goal kicks per 90)

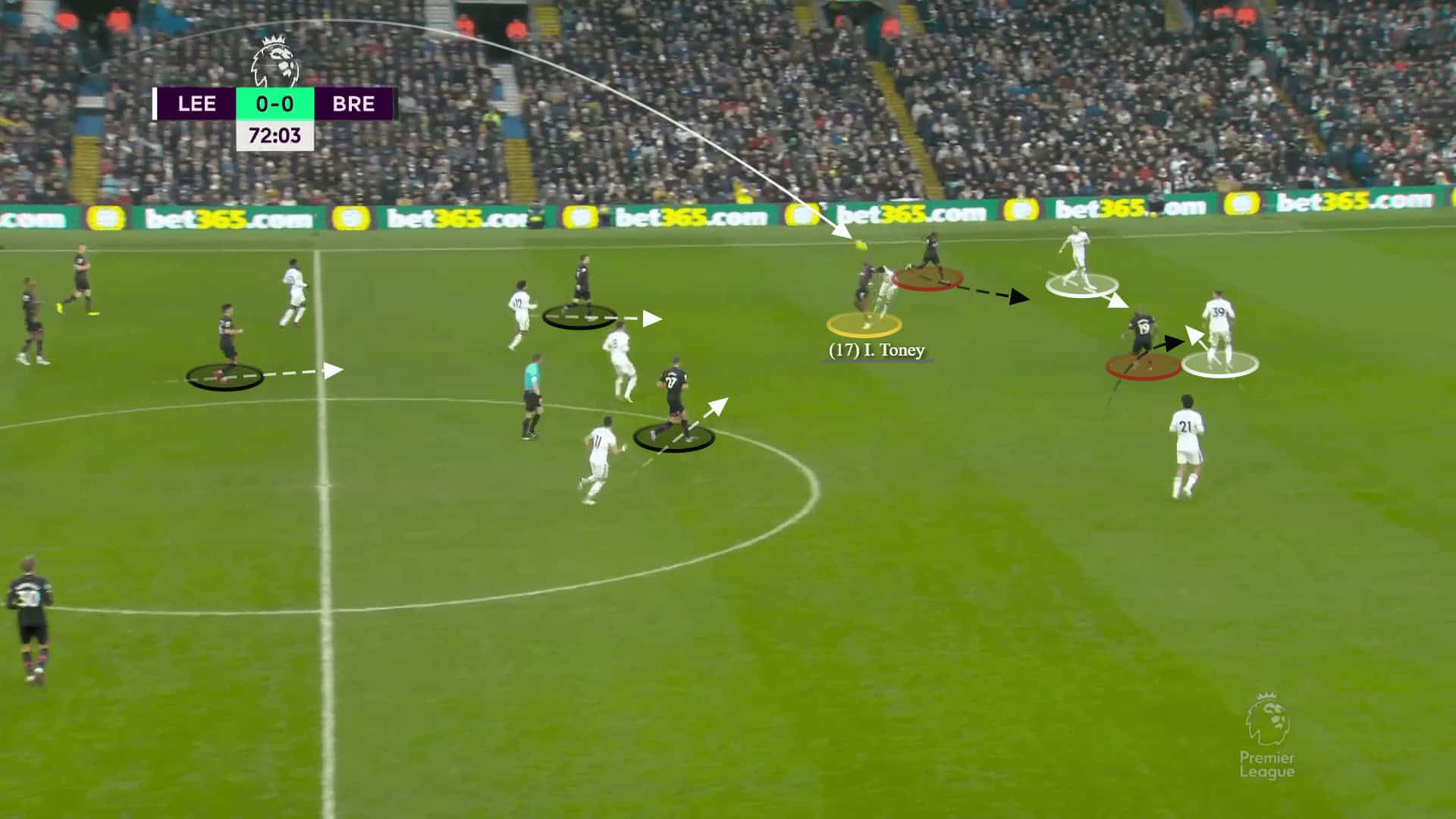

Usually, Raya aims to play the ball to Ivan Toney in the left half-space like in the below graphic.

Meanwhile, others are compact by occupying the centre and left-wing corridors, gaining the positional superiority, ready for any possible lay-offs or flick-ons — Toney won 3.77 aerials per game.

In the previous scene, Ivan Toney’s position in the half-space provoked the centre-back to step up which forced the other CB and FB to cover him and let Henry and Mbeumo free that’s can consider a positional superiority.

It is known that the player in the half-space can play 360° in a less crowded zone than the central which maximizes the chance of making sudden vertical and diagonal runs and minimize the chance of opposition counter-attacks by using the touchline to defend in a lesser area.

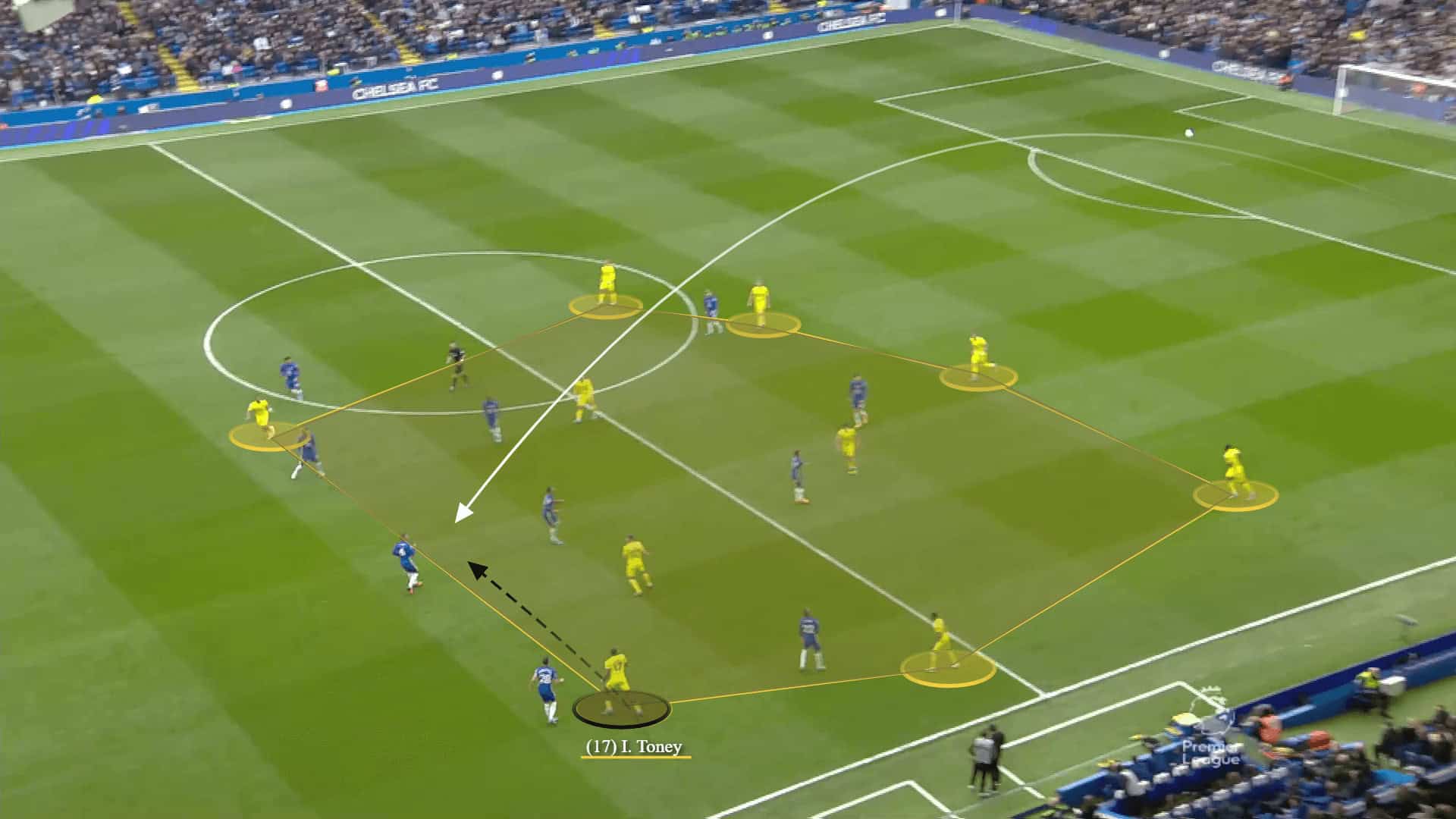

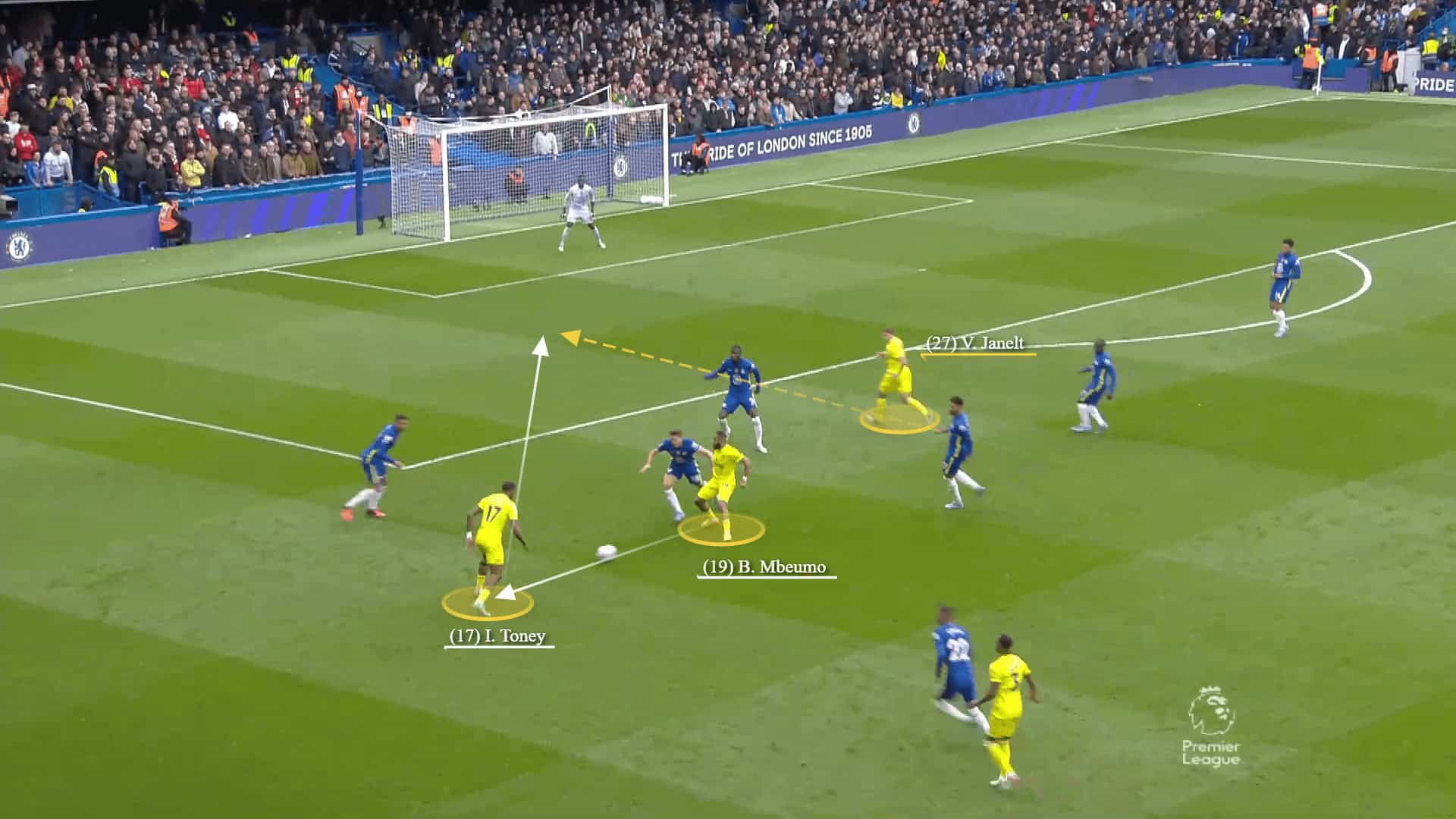

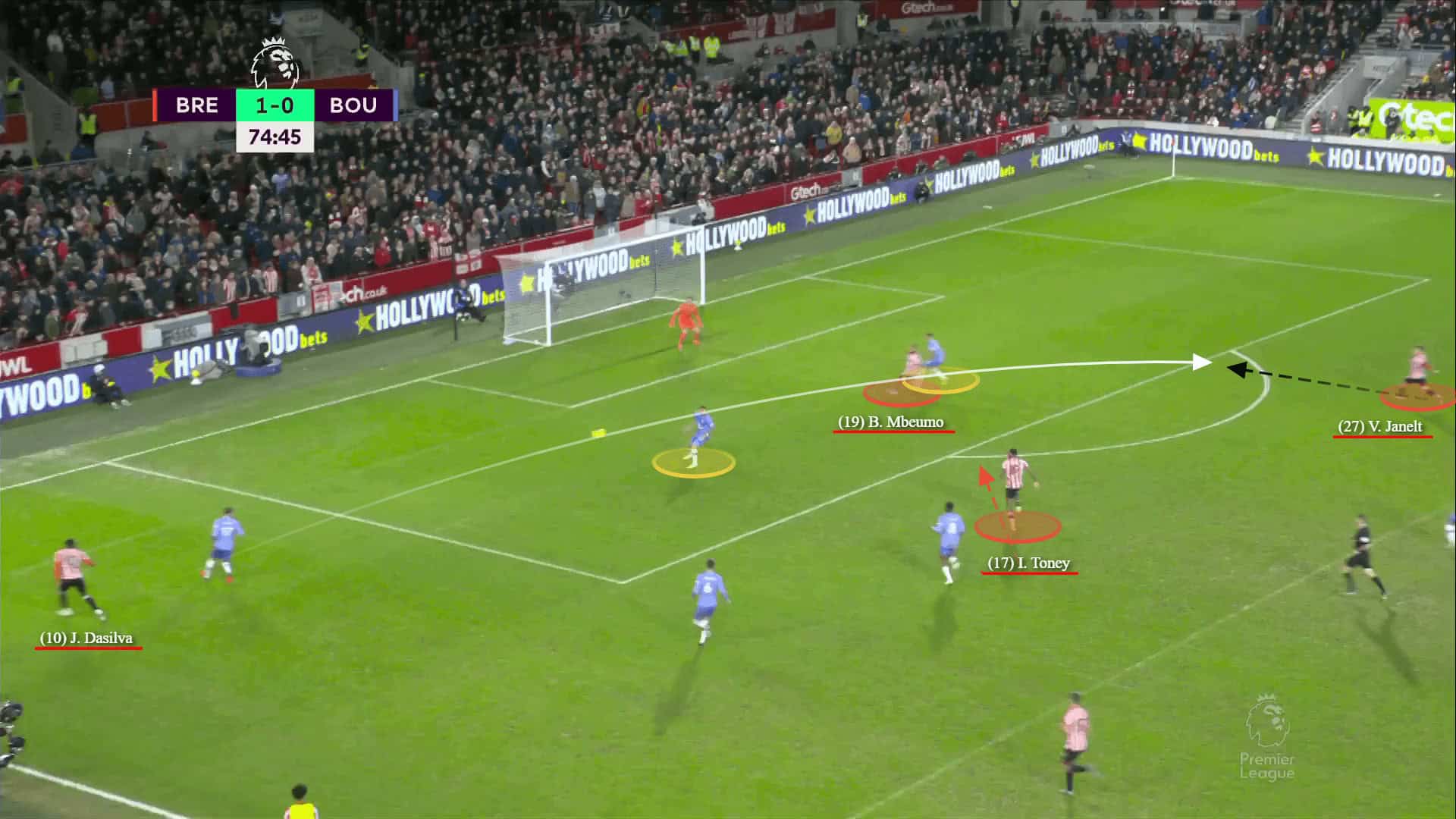

This was exactly applied in their goal against Chelsea in the three below graphics.

Here, the initial positioning of Toney is essential to gain the advantage.

Once Raya launches the ball to the aim in the half-space, Toney moves from the wing to the pre-determined aim to maximize his chance to win the aerial dual, jumping from a dynamic state is better.

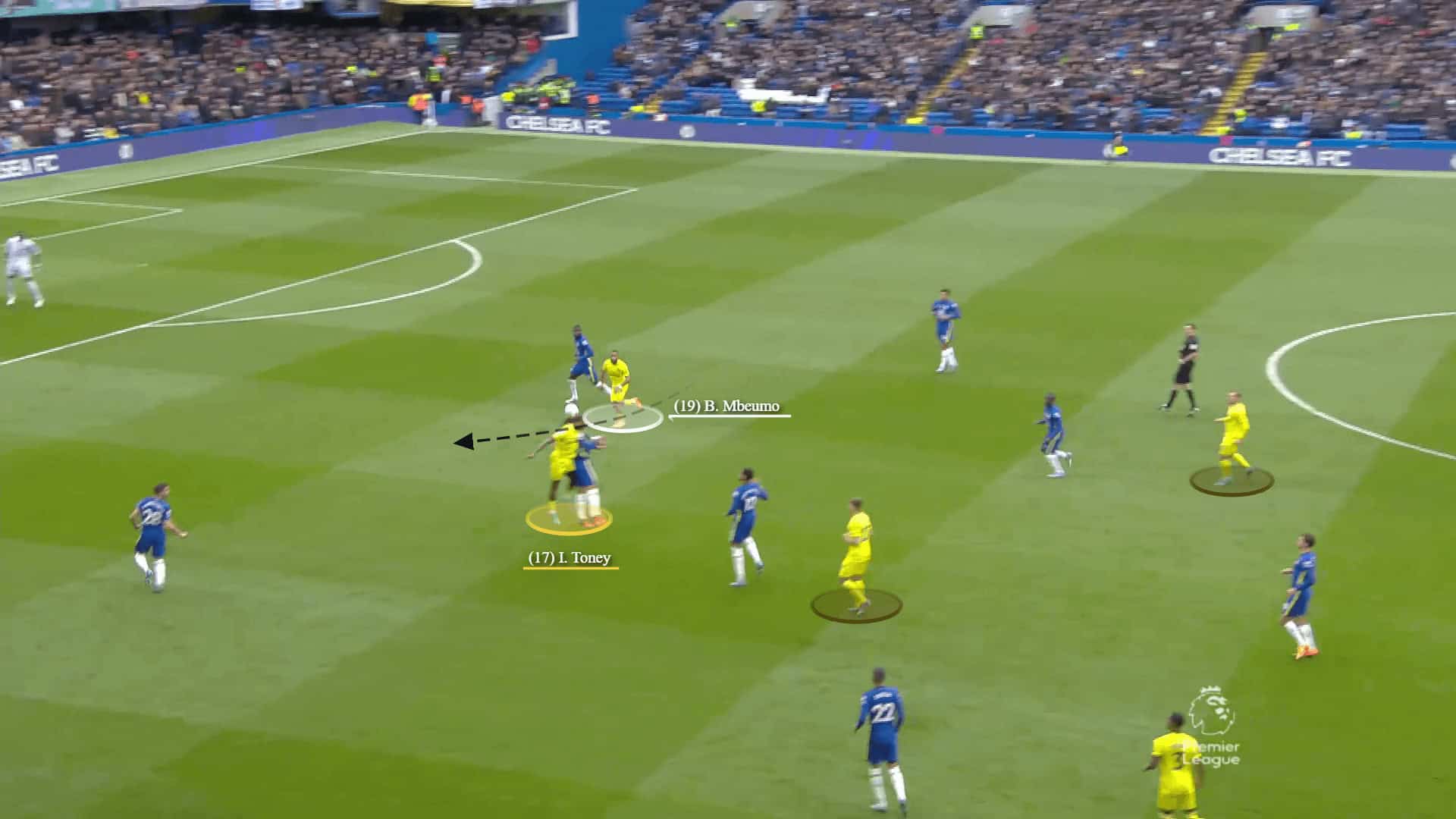

Mbeumo moves to receive the flick-on meanwhile the midfielders are ready for the second ball.

Chelsea’s defence becomes messy meanwhile Janelt moved vertically as the third man to receive Toney’s through ball.

Then, he scores.

There is also another variation from the static mode when facing high pressure, which is to camouflage in playing from the back while keeping the short build-up existing.

The high-pressing team surely has to leave large spaces behind, understanding that there is no offside here from the goal kick, this situation creates many 1v1 and large spaces for running.

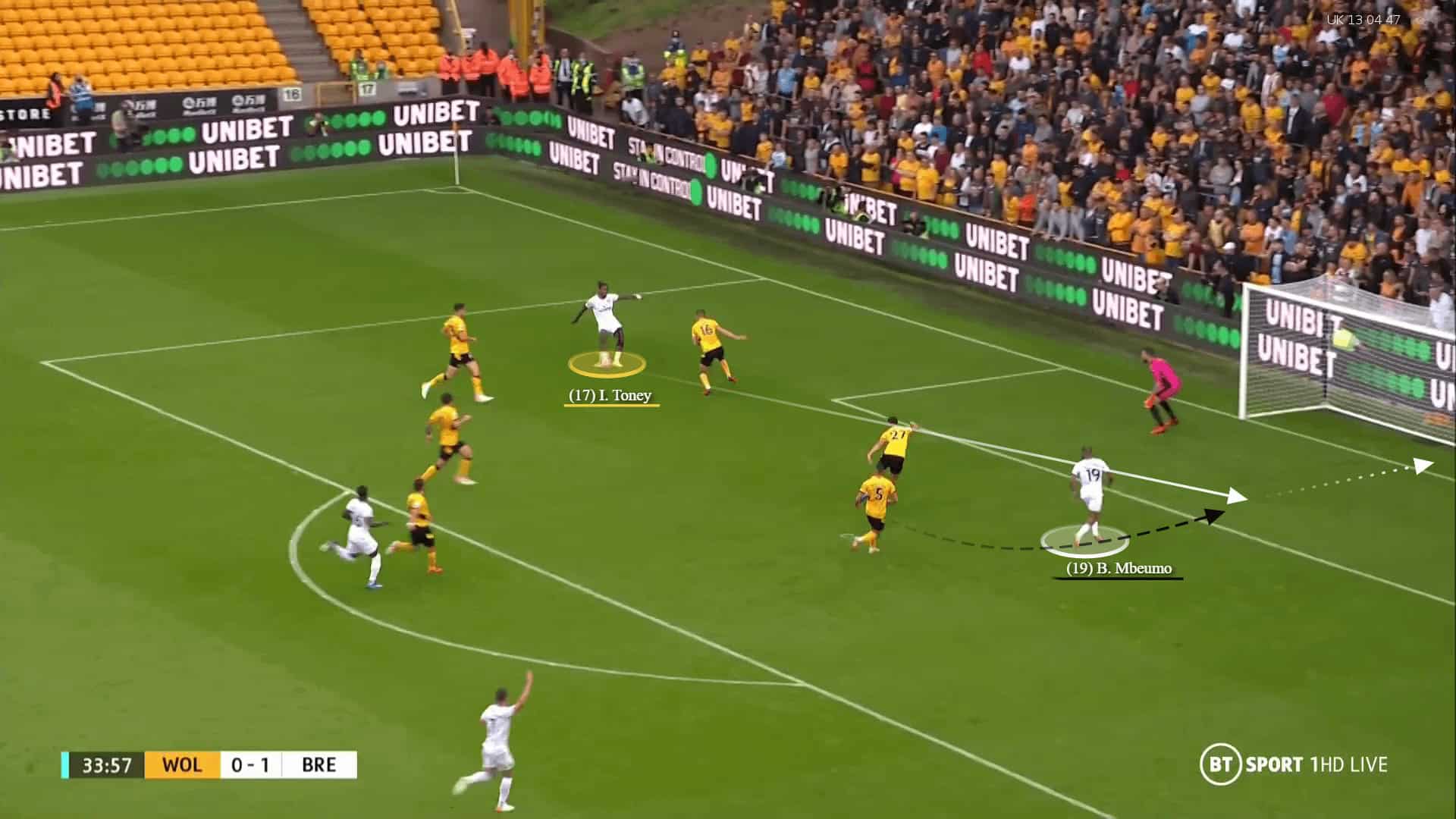

In the below graphics, while Wolves press high, Raya intends to play long ball to Toney on the left side where he is in a 1v1 dual with Kilman.

Once the ball missed their heads, Toney succeeded to gain the dynamic advantage.

It ends up in the net after a brilliant pass from Ivan to Mbeumo who did a double movement to manipulate his defender.

Not all long balls are so sharp to achieve the immediate goal, even if they all want this, but sometimes teams play it to earn larger spaces and resume possession from a higher zone in the pitch.

A well-known example is playing the ball higher to the side for a player with an open body orientation to try to gain a throw-in or win the second ball and restart the possession from the opposition half.

Dynamic

“The long ball is a weapon, a way to change the point of attack quickly and catch the opposition off-guard.” — Tony Pulis

Under these principles, the play is in opposition to the previous one, the ball carrier can be pressed and the team can find it difficult to settle in an organised structure.

The main purpose here is to win the second ball and continue the attack.

Commonly, pressing triggers are utilised here to provoke the opposition to move higher and then direct the ball towards the aim, that’s part of the dynamic element.

There is quite a distinction between winning a second ball in a compact situation and winning the second ball in an open space.

Usually, Brentford are effective and risk losing the ball in order to be direct and win the second ball to reach the goal in the least possible way.

Thomas Frank talked before that they always want to play the long ball accurately, win the second ball and then get a situation of numerical advantage in the box waiting for the cross.

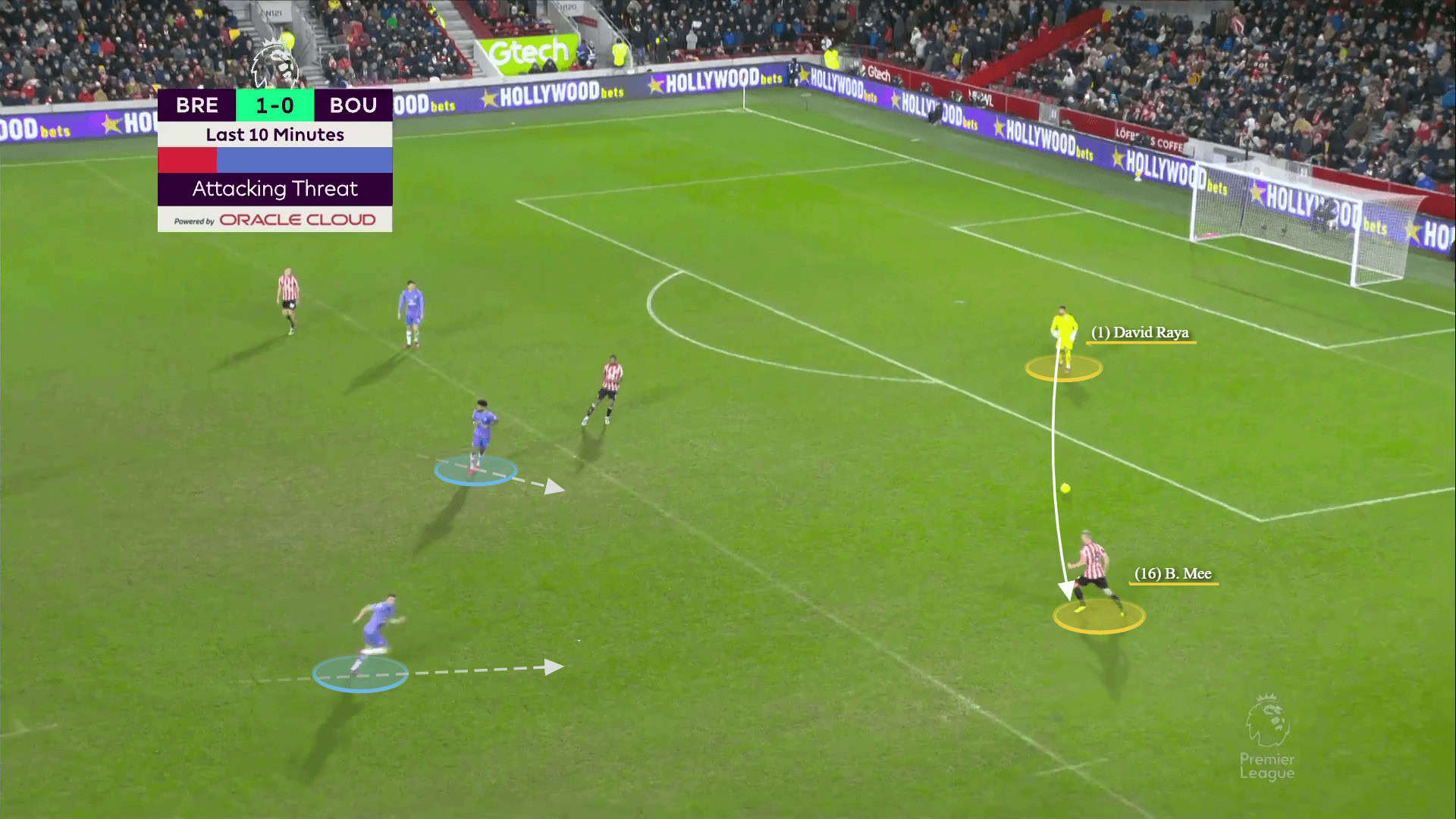

Here against Bournemouth, Raya’s pass to Mee provokes both players to press him and the rest team to step further a little.

After Ben Mee played the long ball into his side, Bournemouth’s fullback who intended to press Brentford’s wing-back then stepped back to receive the ball, made it harder than if he sticks to his initial positioning.

At the same time, Toney engages and the centre-back follows him which opened a big space that can be exploited.

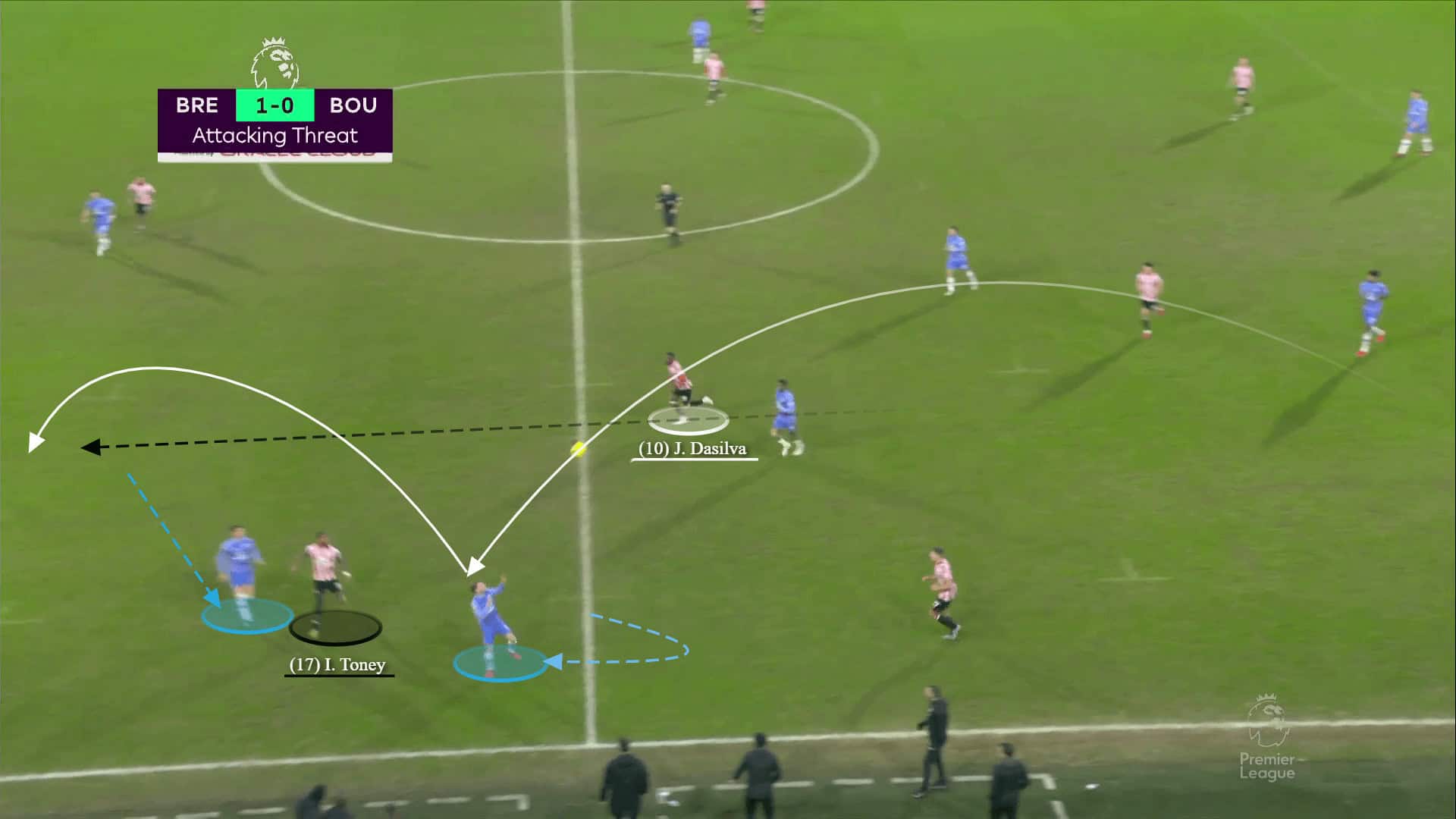

Below, Dasilva recognises the space and then moved to it and received the ball in a large space behind.

Brentford created the favoured situation around the box here below, a 3v2, while Dasilva crossed the ball to the deep-lying runner Janelt who scored the goal.

This situation can be seen a lot from Brentford, also occasionally using the same ideas with a variety of runs and drawing opponents out to restart possession higher or go direct.

Conclusion

The article discusses the concept of pragmatism in modern football and how it has evolved the long-ball approach.

Brentford is cited as an example of a team that has effectively implemented a long-ball approach through the recruitment of suitable players with specific attributes and effective training.

“Football is a simple game, but it’s difficult to play simple.” – Johan Cruyff

Comments