For years, Virgil van Dijk and Liverpool have given no quarter to opponents, attacking opponents with a sense of ruthlessness and relentlessness. The spoils were a Champions League title and the much-coveted Premier League crown.

The tables have turned.

Liverpool is underperforming and van Dijk has come under scrutiny by the global football media. Liverpool’s defensive metrics have never been worse under Jürgen Klopp. Criticism is deserved, but is it rightly placed? Van Dijk is one of the leaders on the team and arguably their biggest star, but does he deserve the degree of criticism he’s receiving?

He’s not alone. Centre-backs play a position that requires perfection. There is no room for error because errors lead to goals against. Much like goalkeepers, centre-backs seem to receive the most attention when they are making mistakes.

Van Dijk’s season sparked a question; why is consistent defensive reliability from centre-backs so difficult? Pulling the veil from that mystery is our objective in this data analysis. This tactical analysis is not exclusive to Liverpool and van Dijk. We all remember Milan Škriniar’s temporary fall from grace under Antonio Conte. We also have high-profile signings who certainly haven’t done poorly this season, but haven’t quite matched the preseason expectations. We’ll look at these cases in search of insights into why centre-backs experience performance slumps.

Virgil van Dijk and Liverpool – a case study

Let’s start with Liverpool because, quite frankly, their fall from grace is staggering, especially given the relative stability they’ve enjoyed during Klopp’s tenure at the club. Pundits will point to Darwin Núñez’s squandering of goal-scoring opportunities, which there is some truth there, and issues along the Liverpool backline. But that level of analysis is just scratching the surface. One or two players are not responsible for this type of fall.

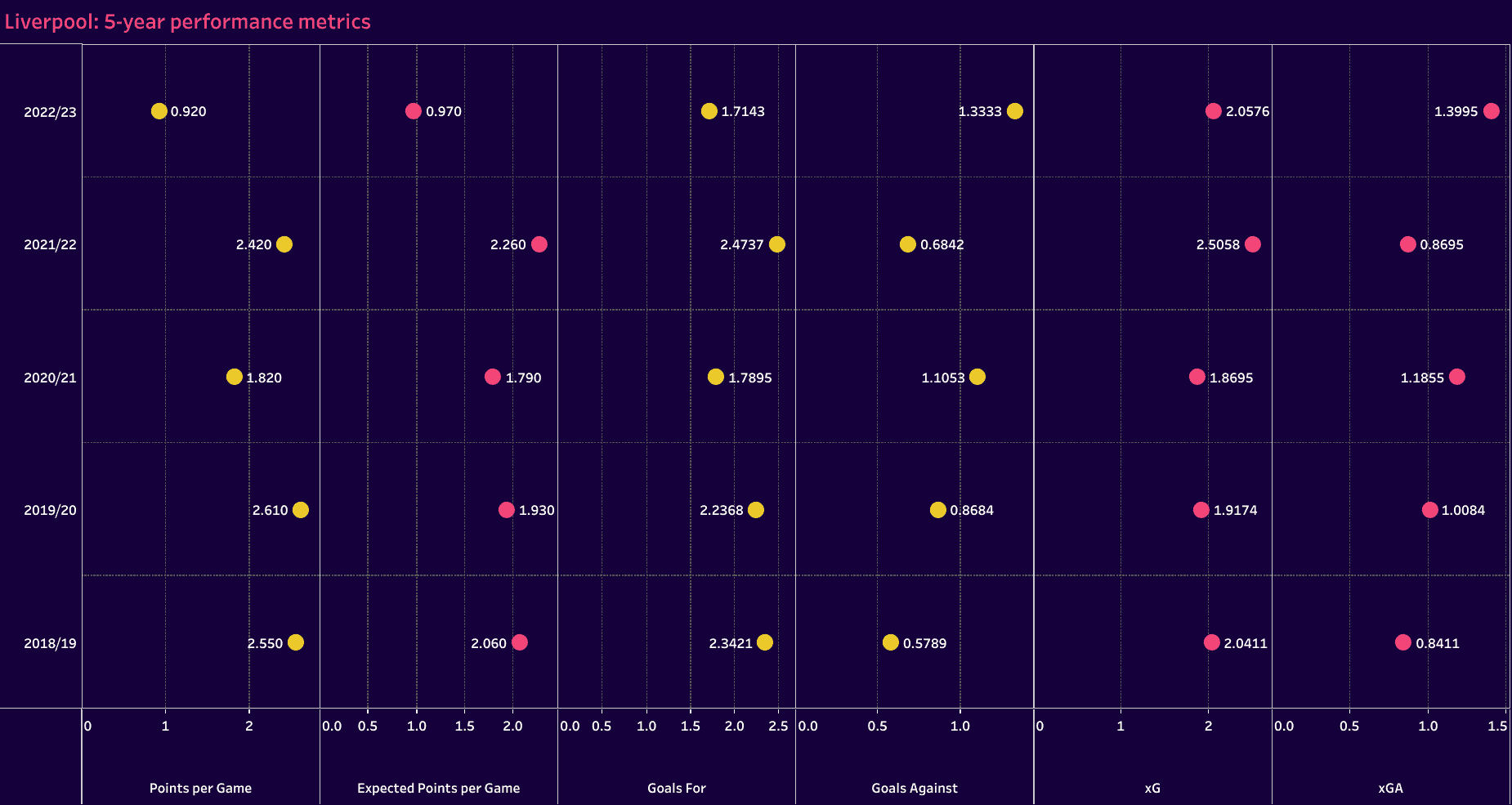

Looking at their 2022/23 metrics, this is Liverpool’s worst season under his reign. For the first time in his Liverpool managerial career, they may miss Champions League qualification when Klopp has managed the full season. You’ll recall during his first year at Anfield, he started the job on 8 October 2015, replacing Brendan Rogers, helping the side to an eighth-place finish.

Compared to the previous four seasons, the 2022/23 campaign has Liverpool setting lows in points per game, expected points per game, goals for, goals against, and xGA. Liverpool’s second-worst mark in points per game, at least during this five-year span, came during the substandard 2020/21 season where they averaged 1.82 points per game. That’s nearly double their rate in 2022/23. More worrisome is the number of goals they allowed per game. 1.33 goals against P90 isn’t an aberration either. Comparing goals against to xGA, Liverpool’s reality is aligned with the expected outcomes.

The current campaign marks a significant drop off from recent years. Maniacal defending in the opponent’s half of the pitch has become part of the Liverpool legacy under Klopp. Allowing less than a goal per game had become the standard, but this season, it’s nothing more than a dream.

Given the presence of van Dijk and an experienced backline that has spent many years together, these results are shocking. It was just four seasons ago that van Dijk finished in the top three of Ballon d’Or voting.

But have his performances dropped off that significantly this year?

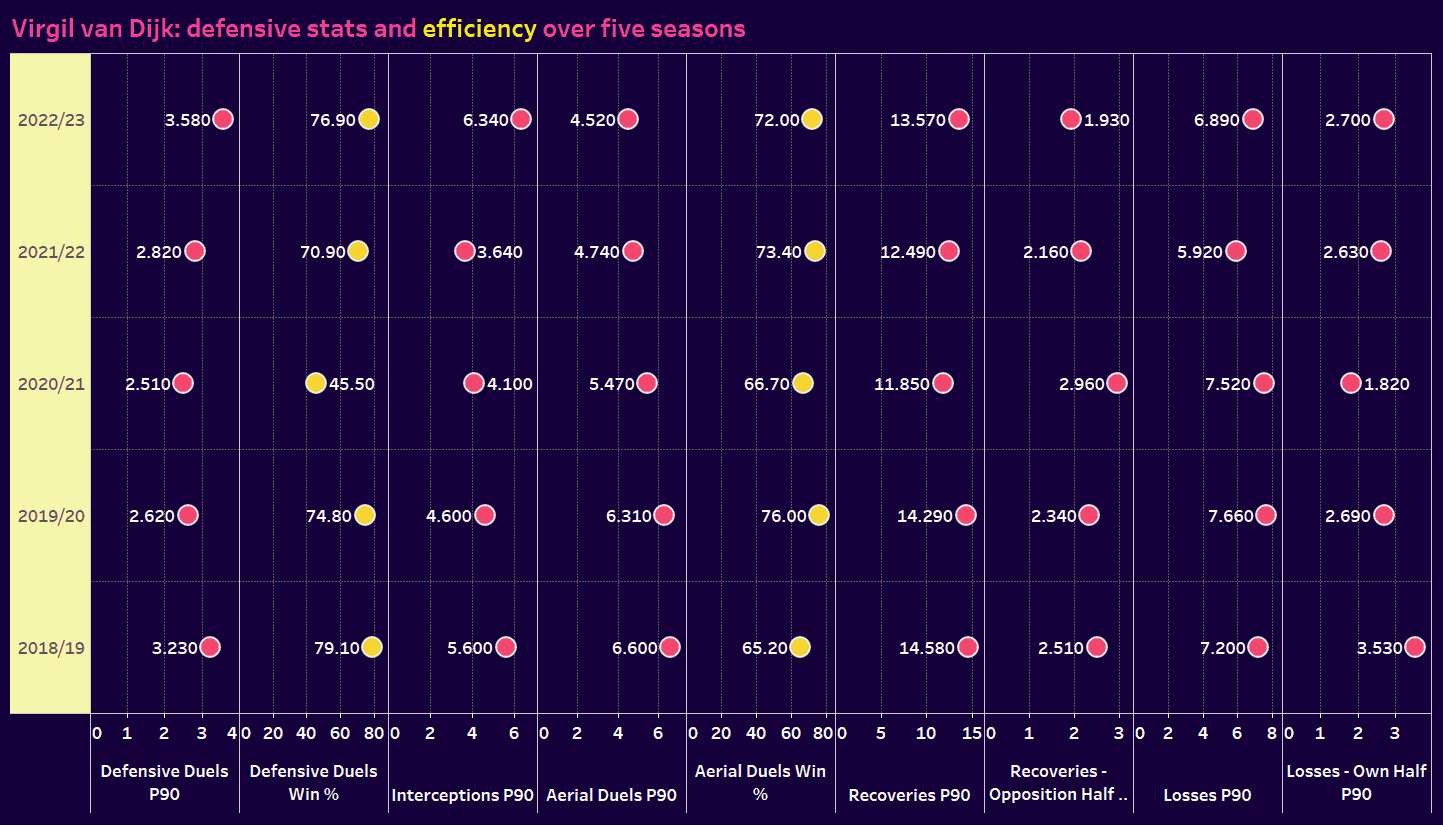

The simple answer is no, they have not. If anything, the statistics point to him having a good season overall. Looking at his defensive stats and efficiency, which are marked with the yellow points, he’s performing well across the board, including his defensive duels engaged and win rate, interceptions, aerial dual win percentage and recoveries P90. He has even scaled back his losses P90, though the number of times he loses the ball in his own half is on par with previous seasons.

But look closer. Look at the increases in defensive duels P90 and interceptions P90, as well as the decrease in opposition half recoveries. Based strictly on the statistics, he’s busier than ever and defending deeper in his half. That’s not a reflection on his personal performances, but an indictment of the season Liverpool is having.

Centre-backs run the show from the back, but they are still largely dependent on the performances of the players in front of them. When the high press isn’t generating turnovers and 50/50 long-range passes of the pitch, the centre-backs suffer. When the midfield can’t seal opponents in or give the ball away in poor positions, the centre-backs feel the additional strain. That’s especially the case for centre-backs who man a high line. There’s simply too much ground to cover when the players in front of them can’t make play more predictable.

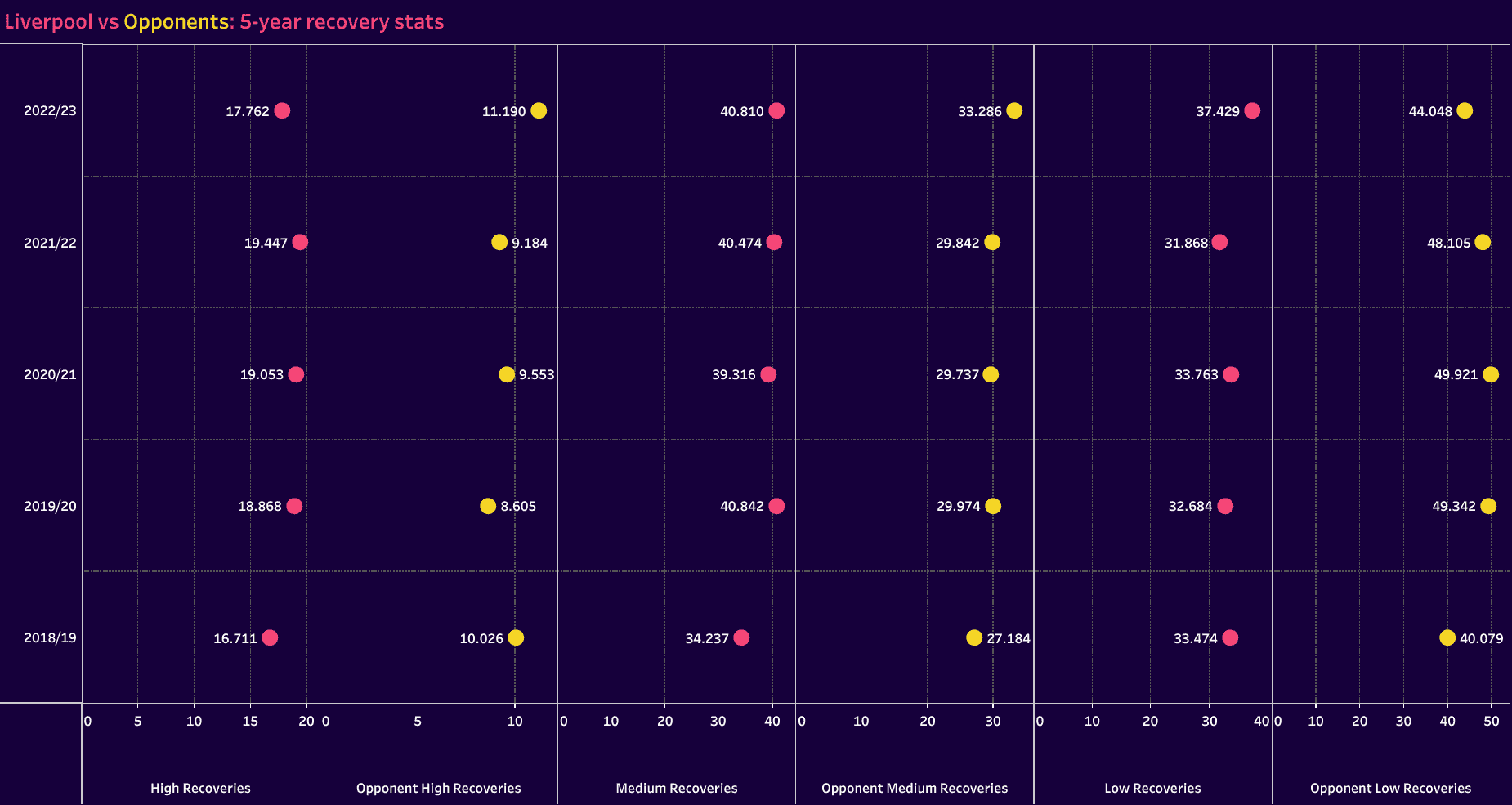

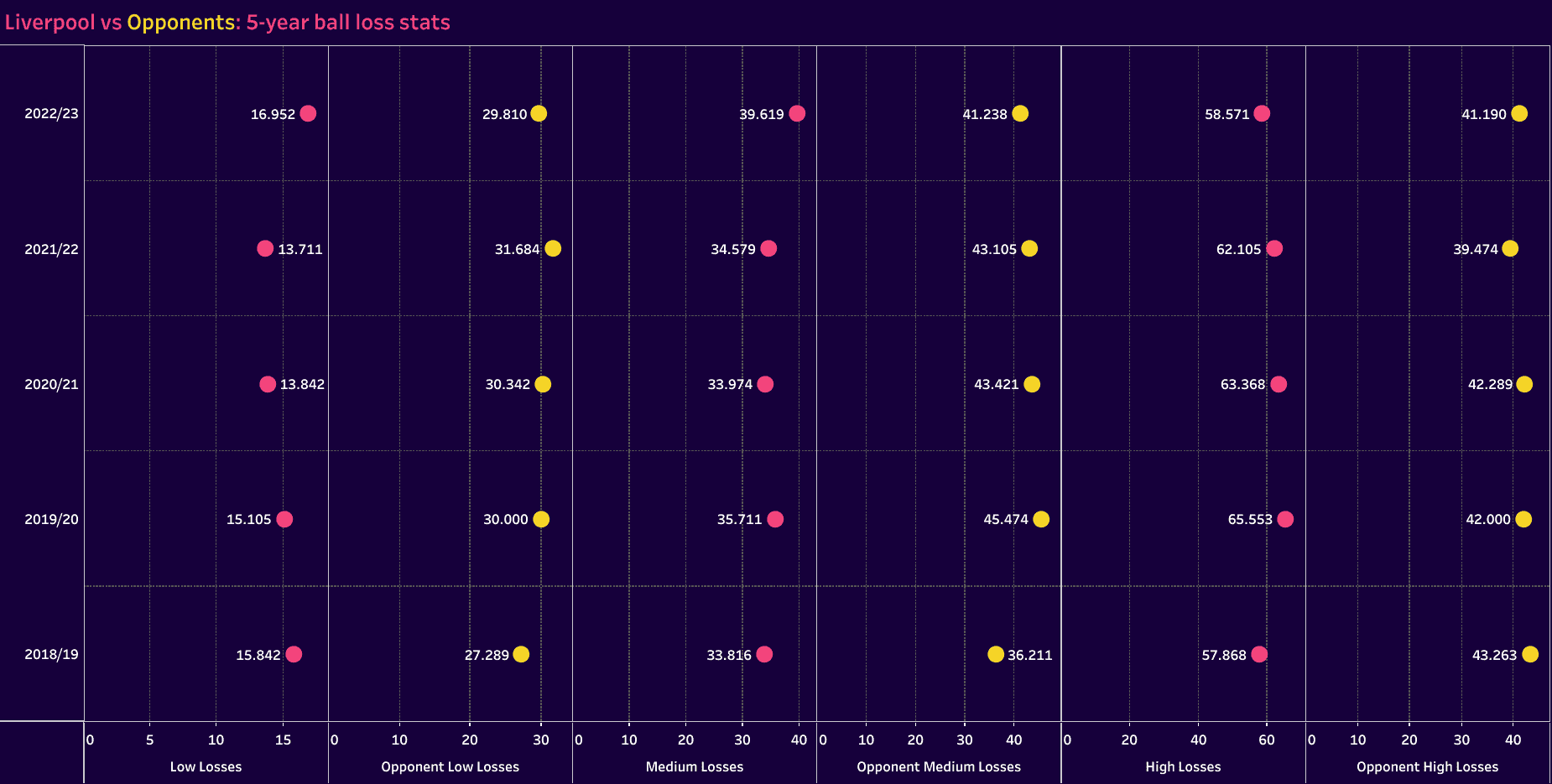

Given Liverpool’s reliance on the forwards and midfielders to produce turnovers and low-percentage passes from the opposition’s backline, we went straight to the source, looking at Liverpool’s recoveries across the thirds of the pitch comparing the current campaign to the four previous. The opposition’s data is included in yellow.

Liverpool’s high recoveries remain ahead of the 2018/19 campaign, but they lag behind the previous three seasons. In the middle third of the pitch, the current campaign’s stats are 0.032 off of the five-year high. It’s the defensive third stats that offer the most insight. With 37.43 low recoveries P90, this is easily the busiest Liverpool has been at the back.

Part of that comes down to self-inflicted injuries. Opponent high recoveries registered at 11.19, a five-year high. Likewise, 33.29 opposition recoveries in the middle third is also the highest mark. Predictably, opponent low recoveries are at a five-year low. Liverpool is spending more time defending in their own half of the pitch, in part because of their own mistakes in their half.

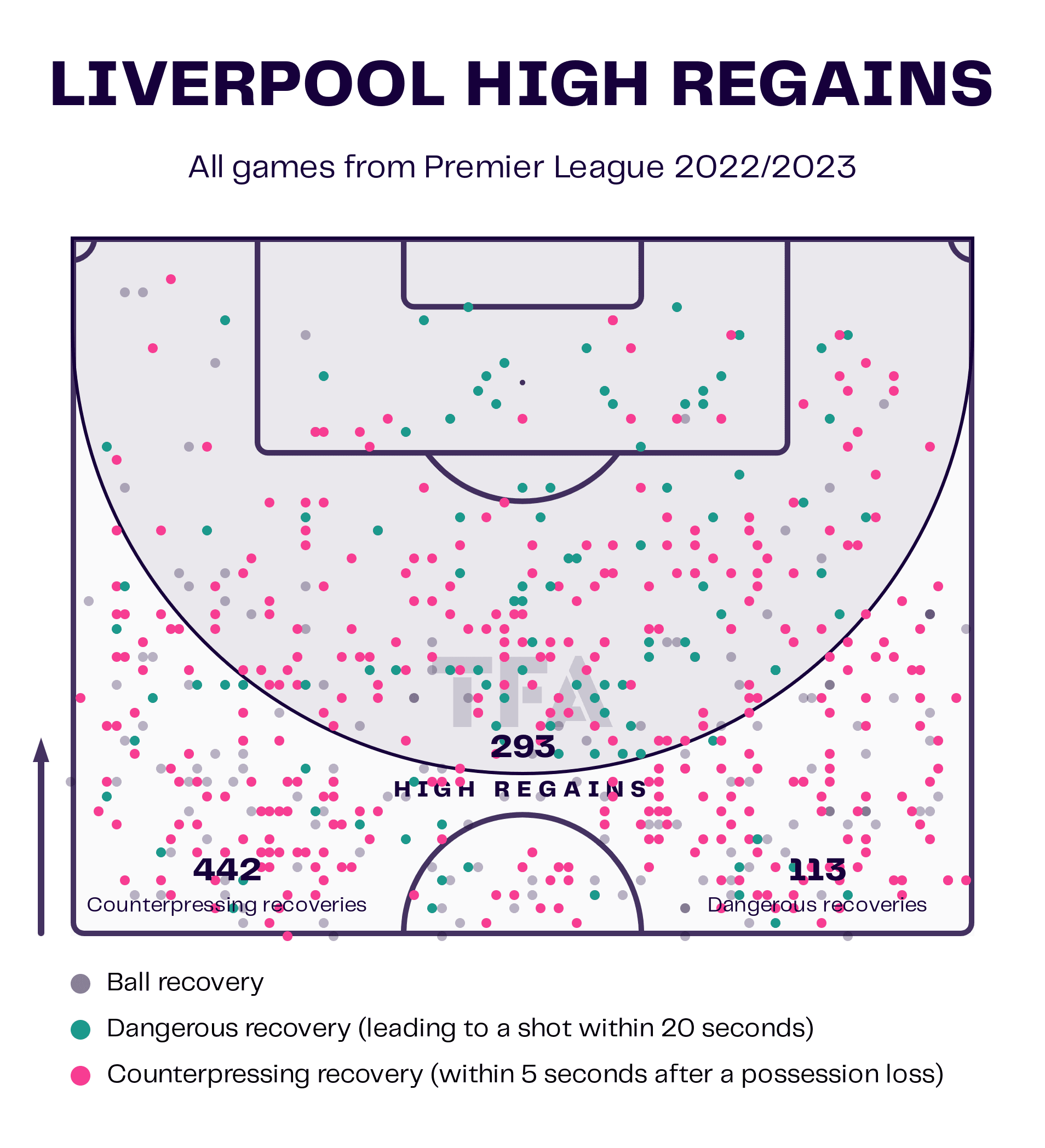

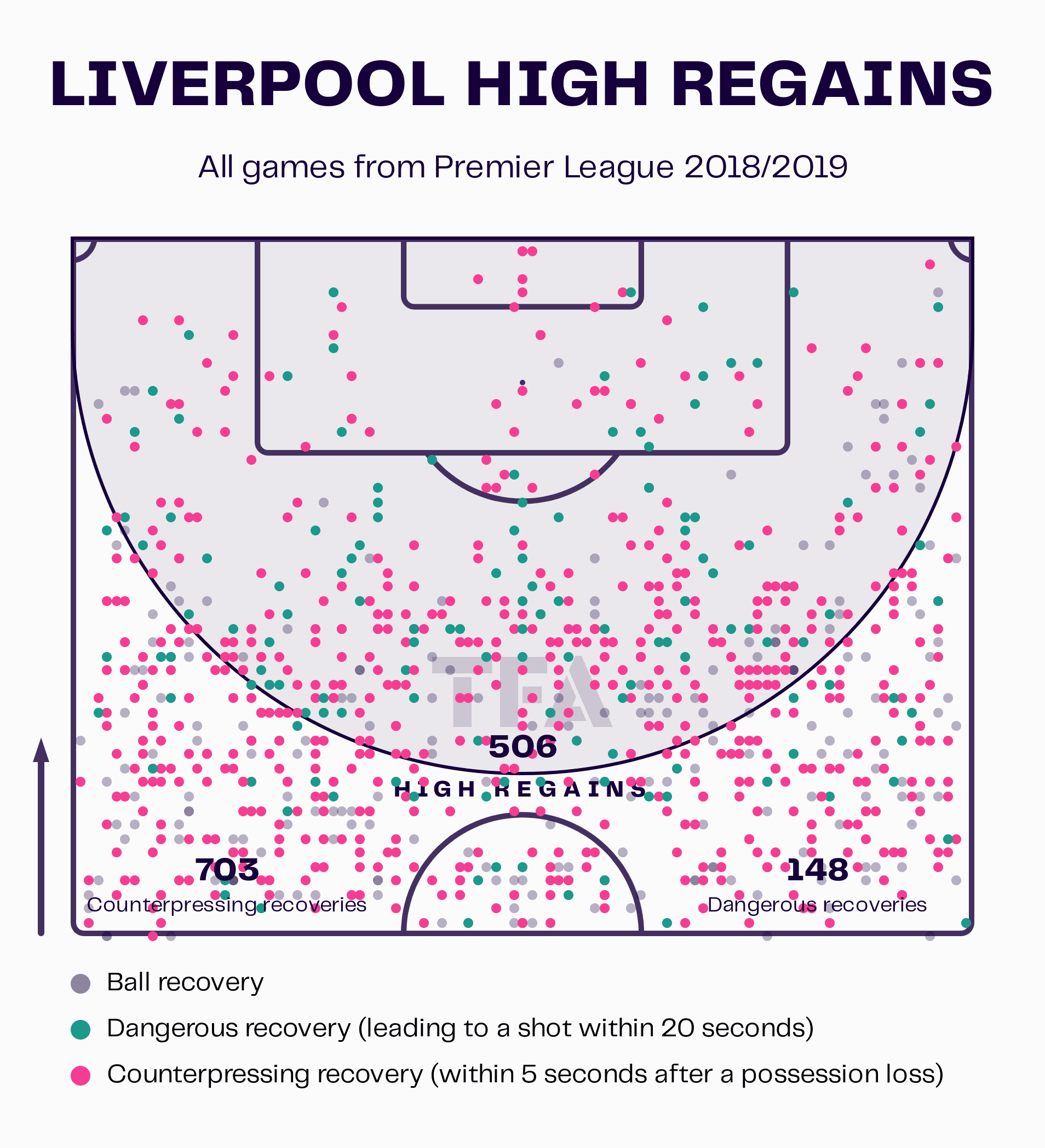

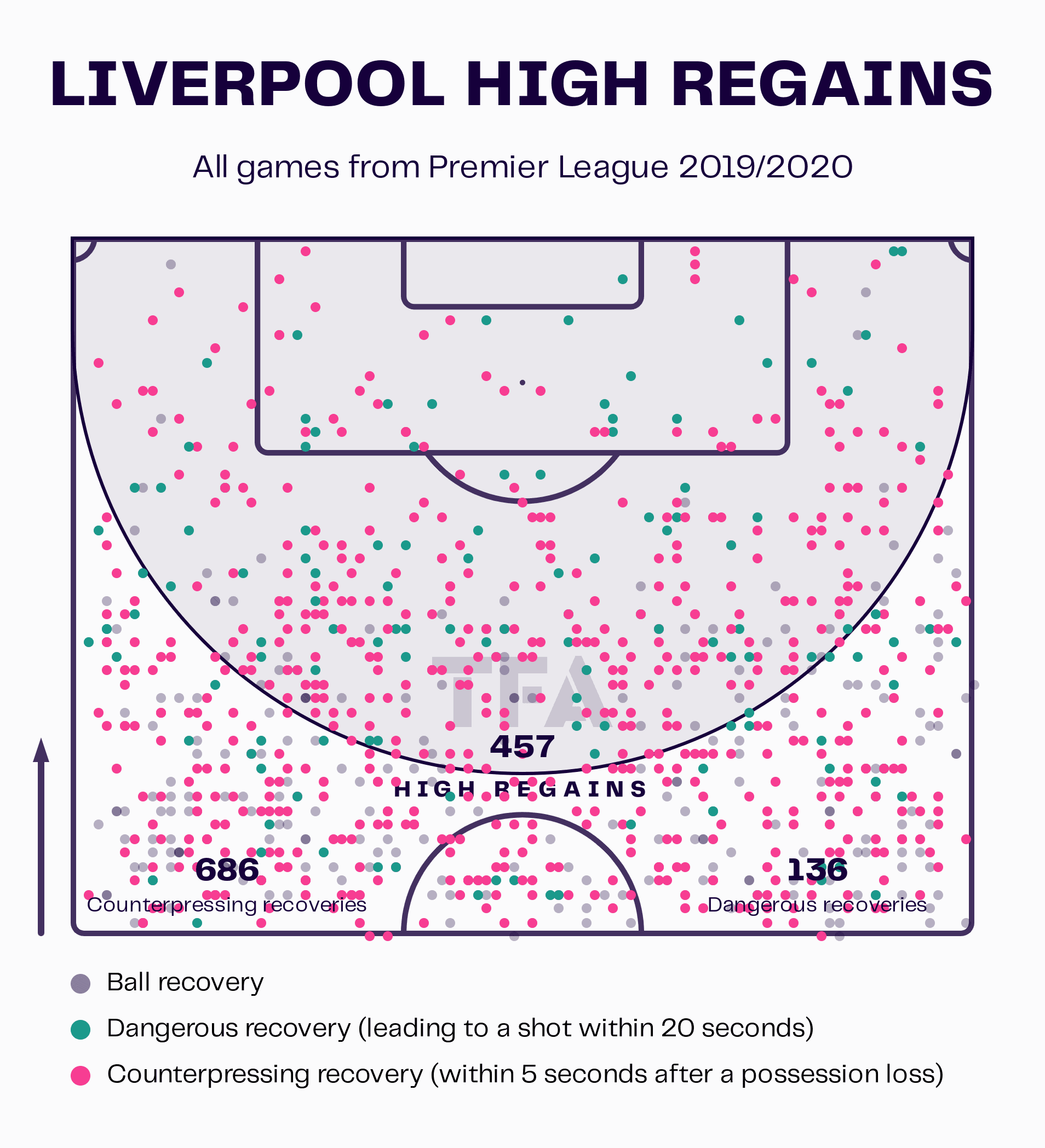

Going into greater detail, Liverpool’s high press really hasn’t been bad. In fact, the numbers are generally positive. Mapping out Liverpool’s high regains, they’re averaging 13.32 P90, which equals the 2018/19 team. They’re generating 20.09 counterpressing recoveries P90 with 5.14 registering as dangerous recoveries, meaning they lead to a shot within 20 seconds.

Let’s contextualize this data. In 2018/19, Liverpool’s Champions League winning campaign, the side averaged 13.32 high regains, 18.5 counterpressing recoveries and 3.89 dangerous recoveries, each on a P90 minutes basis.

The following season, those numbers dropped to 12.03 high regains, 18.05 counterpressing recoveries and 3.59 dangerous recoveries.

Of the three seasons, the current campaign offers the best numbers in each category. The high press is working, but Liverpool is spending less time in the opposition’s half of the pitch due to their issues in possession.

Defensive transitions are another element. These moments are difficult because the team transitioning to defence must move from an expansive shape to a more compact one quickly, all while the opponent races to goal. Given the lack of structure, the opponents typically have more space to attack and higher-quality options to get to goal. When centre-backs and defensive midfielders have to routinely diffuse counterattacks that start in their own half, they can only hold off the opposition for so long. At some point, profligacy at the back comes back to haunt you.

Liverpool’s ball loss statistics back up that thought. 16.95 low losses P90 or a five-year high, as are the 39.62 medium losses. To reinforce the point that Liverpool is spending less time in the final third, high losses are down to 58.57 P90, short of the five-year high at 65.55.

Opponents are also losing the ball less often in their defensive third. Opponent low and medium losses rank fourth out of five for Liverpool.

Liverpool is in the midst of a difficult season, but the numbers support the idea that the press is working well and that their leader at the back is having another strong campaign. The issues are a result of Liverpool’s in-possession tactics and decision-making. Press resistance has been an issue and the backline and defensive midfielders are feeling the strain of poor ball security. Centre-backs are often among the first to receive blame when things go awry, but in this instance, the criticism of van Dijk is largely unfounded.

Positional adjustments and the coaching carousel

The shock of Liverpool’s decline is in part due to the stability of the club. Between the long-term presence of their manager and the few number of moving pieces on the roster, Liverpool has done well in recent years to keep their court together while bringing in fresh blood to keep the squad refreshed and fight complacency.

Other centre-backs don’t have that luxury. Even when looking at the top centre-backs in the game, they commonly have a new manager every two seasons as well as a new addition to the backline. If the club has a consistent game model and recruits the manager based on his willingness to implement the club’s preferred tactics, the transition from one manager to the next is relatively easy.

It’s when there is a divergence from one manager to another that issues arise. A shift from one game model to another one entirely presents a learning curve for the players. As the players higher up the pitch learn their new roles and settle into the new manager’s understanding of the game, the centre-backs must help their teammates quickly adapt to the new demands, which in turn helps the centre-backs manage the game.

This was evident at Inter Milan when Conte replaced Luciano Spalletti. In 2018/19, Inter spent their season in a back four with some variation of a three-man midfield. Spalletti rarely deviated from that system and the game model was consistent. Heading into 2019/20, Conte arrived and immediately implemented a back three, which is all Inter played. That had a significant impact on Škriniar.

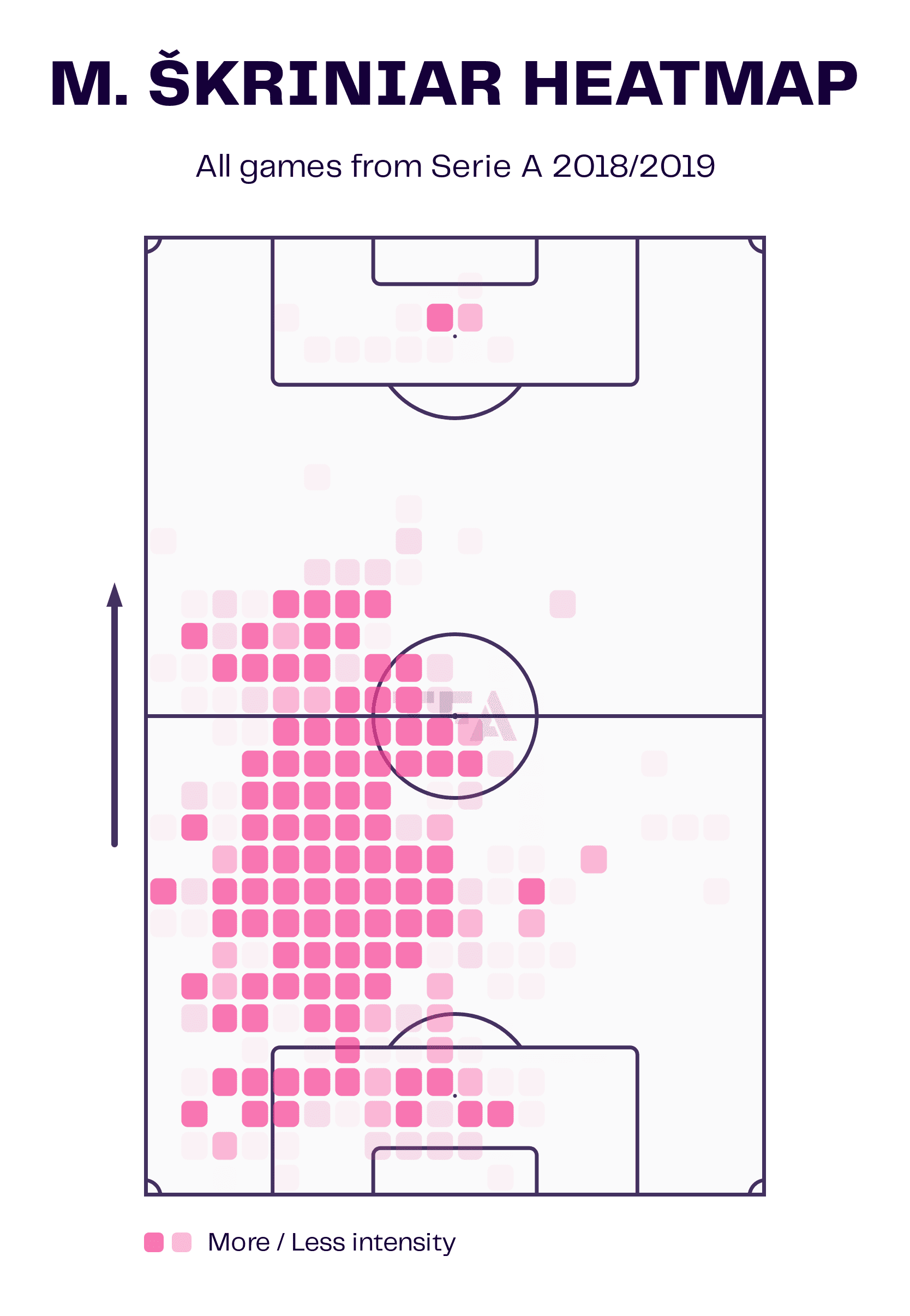

Most will recall his fall from grace from one year to the next. Under Spalletti, he was the side’s left centre-back and anchored a very strong defence. Rumours linked him across Europe. He was in demand after a dominant 2018/19 campaign.

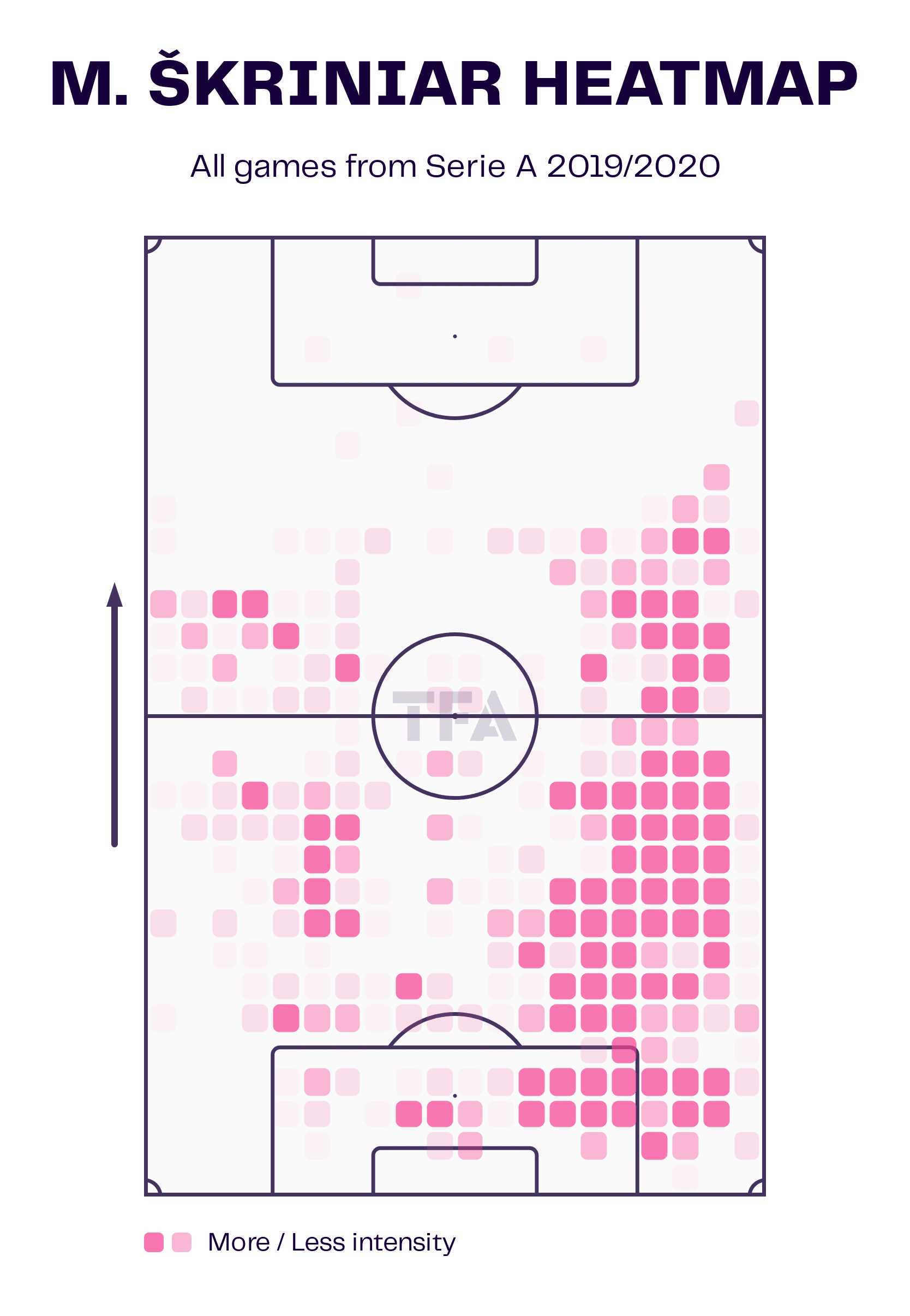

Comparing the heat maps from the two seasons, we see the massive variation in his positional responsibilities. He bounced from left centre-back to right centre-back throughout the season. The right-footed player would seem a more natural fit on the right side, but he couldn’t replicate the performances of the previous campaign. Playing on the left side of a back three was problematic as well given that he took up a wider position which changed the way he oriented his body to his teammates.

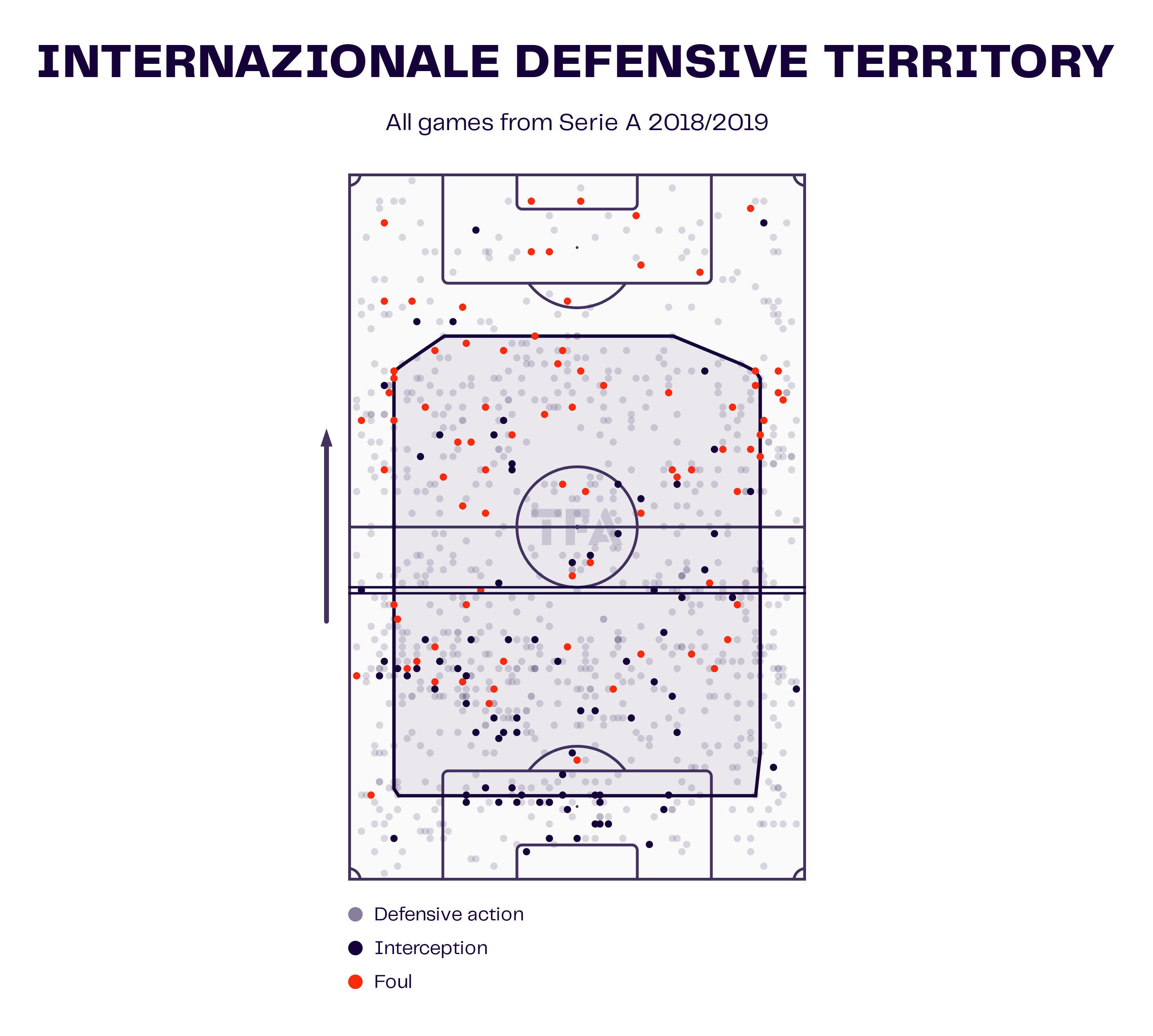

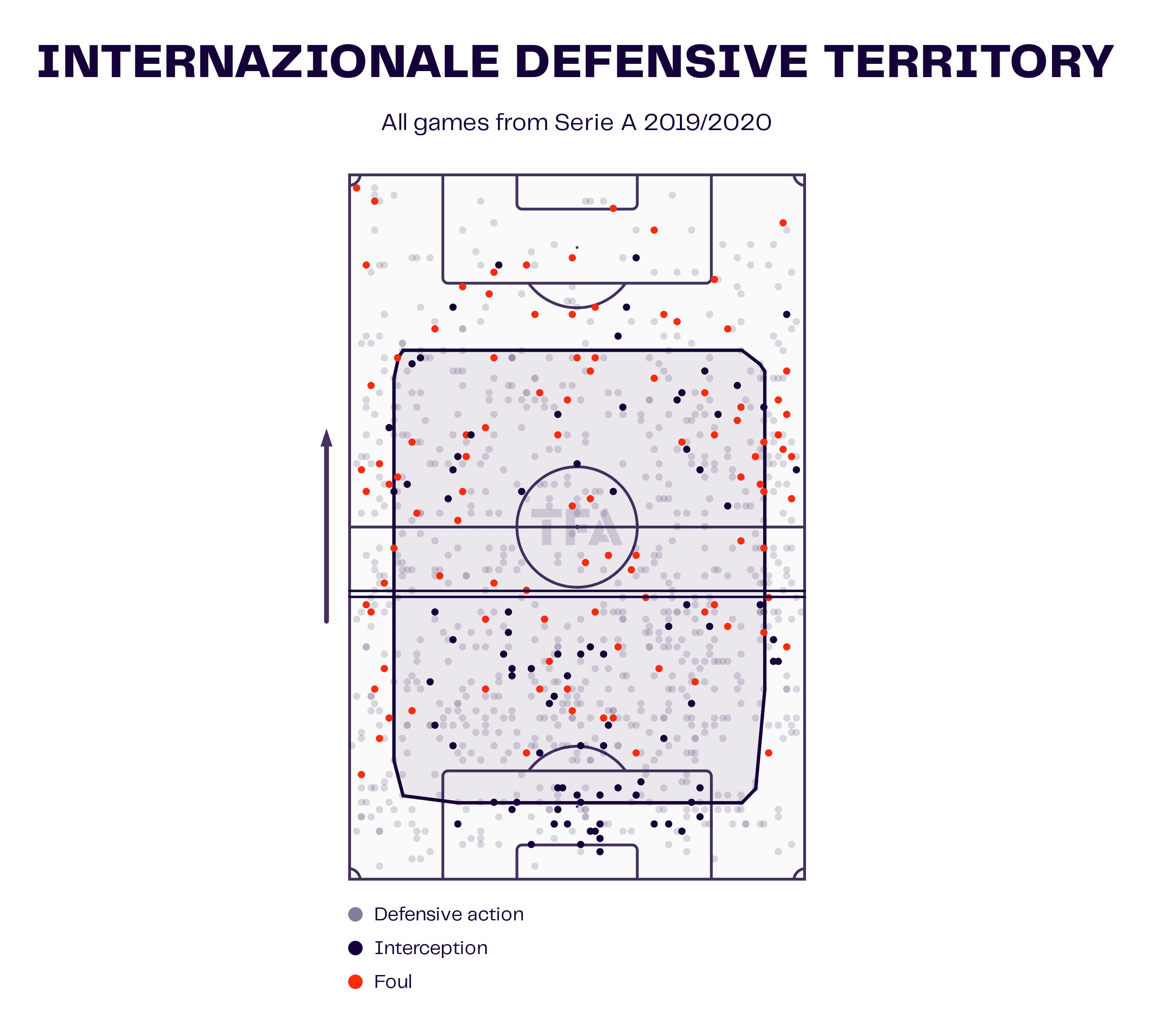

Inter Milan’s defensive territory changed as well. We do see some consistency with the area of engagement and the average recovery line, but looking at the two images in greater detail shows more variation in where Inter Milan engages the opponent. In 2018/19, Škriniar’s left half-space was a hub of activity. Inter could funnel play to his side and allow him to engage the opponent, as well as structure his side.

The following season under Conte, there’s less activity deep in the half-spaces and more engagement centrally. Opponents had more success accessing the central channel. Film study is necessary to confirm any assumptions about the way opponents attacked Inter, but it does appear opponents had more success getting between the lines. There were also more defensive actions in and around the box in the central channel and half-spaces.

Conte’s Inter looks less secure centrally and in midfield, which impacts the way the centre-backs engage the game. There’s the additional issue that one of the star players, Škriniar, was removed from his role as the left centre-back in a back four and alternating between the left and right in a back three.

It was a poor season for the Slovakian. Fortunately, each of the past three seasons has seen him rebound to that 2018/19 level. In fact, he’s in the news now with the potential move to PSG on a free transfer this summer. With a French side splashing the cash to secure his services, we do get the sense that his miserable 2019/20 campaign was largely a product of working with a new manager in an unfamiliar role. From a psychological standpoint, we also have a star player being removed from a role that made him a household name, which is sure to impact the mental state of the player.

2019/20 was a blip on the radar. Škriniar’s talent was there all along, but changes to the managerial position, his role within the team and the team’s tactics had a significant impact on his performance.

Transfers and change in supporting personnel

Expectations were high for both Antonio Rüdiger and Kalidou Koulibaly. The two players moved to new clubs last summer and are tightly connected as one move was a result of another. As Rüdiger swapped Chelsea blue for Real Madrid white, Koulibaly left Serie A’s surprise front-runner, Napoli, to replace Rüdiger at Chelsea.

Though neither transfer has lived up to the billing, at least not yet, both players have had good starts with their new clubs. Rüdiger’s path two minutes is complicated by the Champions League-winning duo of Éder Militão and David Alaba. Though the Austrian is a phenomenal left-back, he prefers to play centre-back at this stage in his career. That has put Rüdiger in a strange position, forcing him to register minutes at outside-back in addition to spot starts at centre-back.

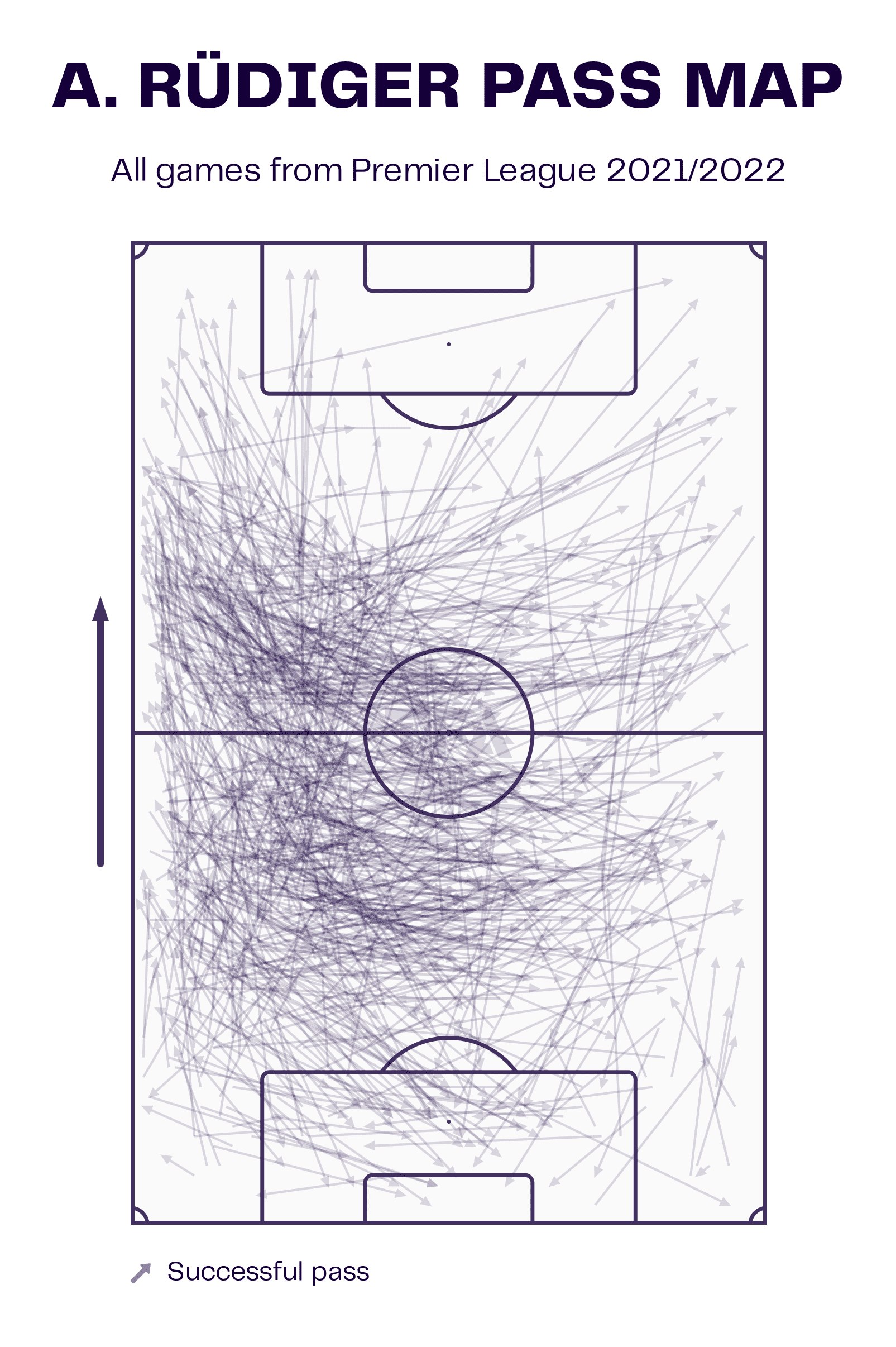

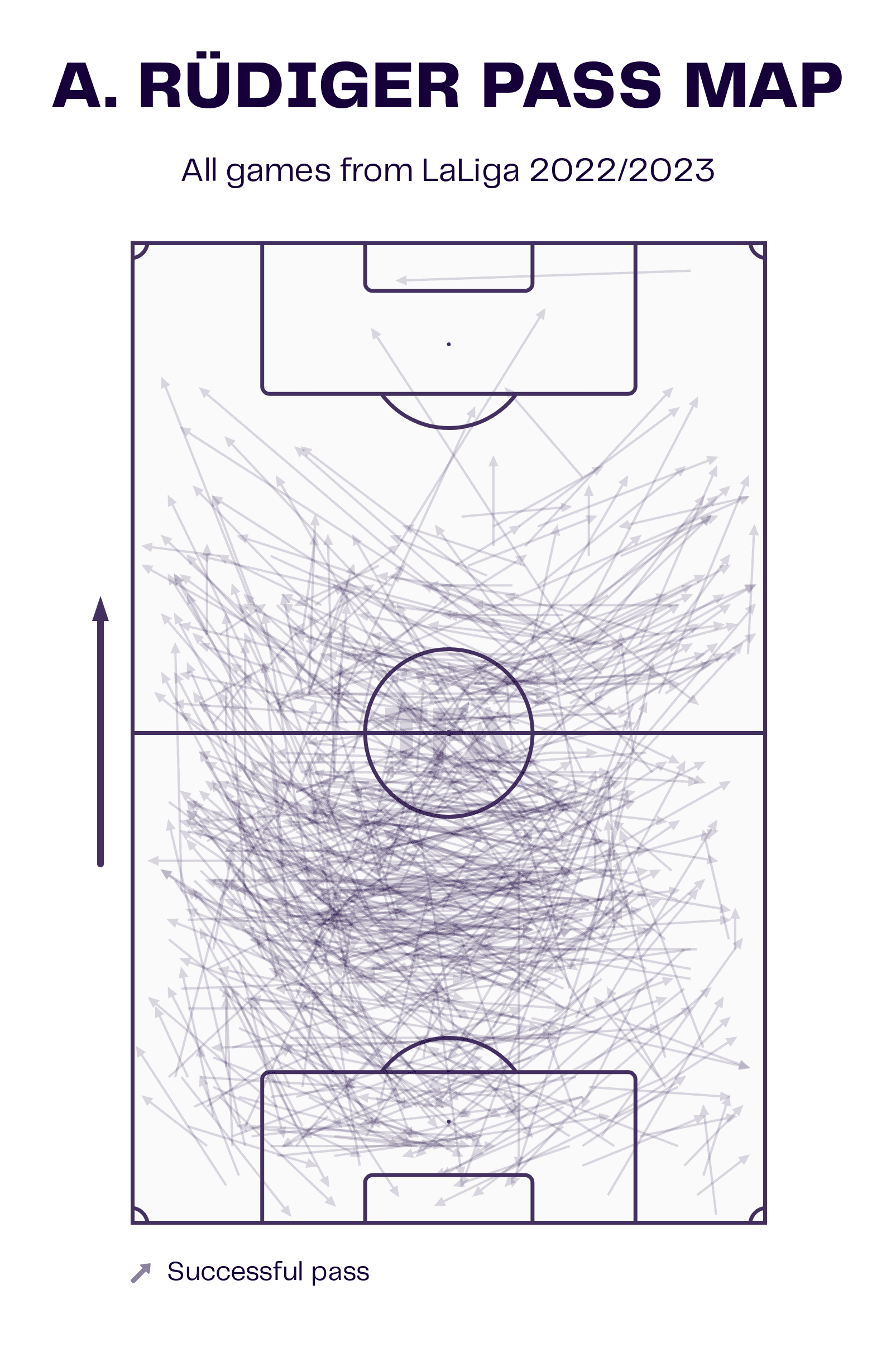

Much like Škriniar, Rüdiger has had to make a lot of adjustments. He not only has a new manager and teammates, but he’s also moving from a back three to a back four. His use at any of the four spots along the backline adds another wrinkle to the equation. His pass maps offer excellent insight into the adjustments he’s had to make from last season to the current campaign.

At Chelsea, his passes typically went through the left half-space, which is understandable given his role as the left centre-back in Thomas Tuchel’s back three. Now at Madrid under Carlo Ancelotti, his pass map shows equal colouration through the central channel and left half-space. In fact, his passes covered the width of the box, which shows how versatile he has been for the Spanish champions.

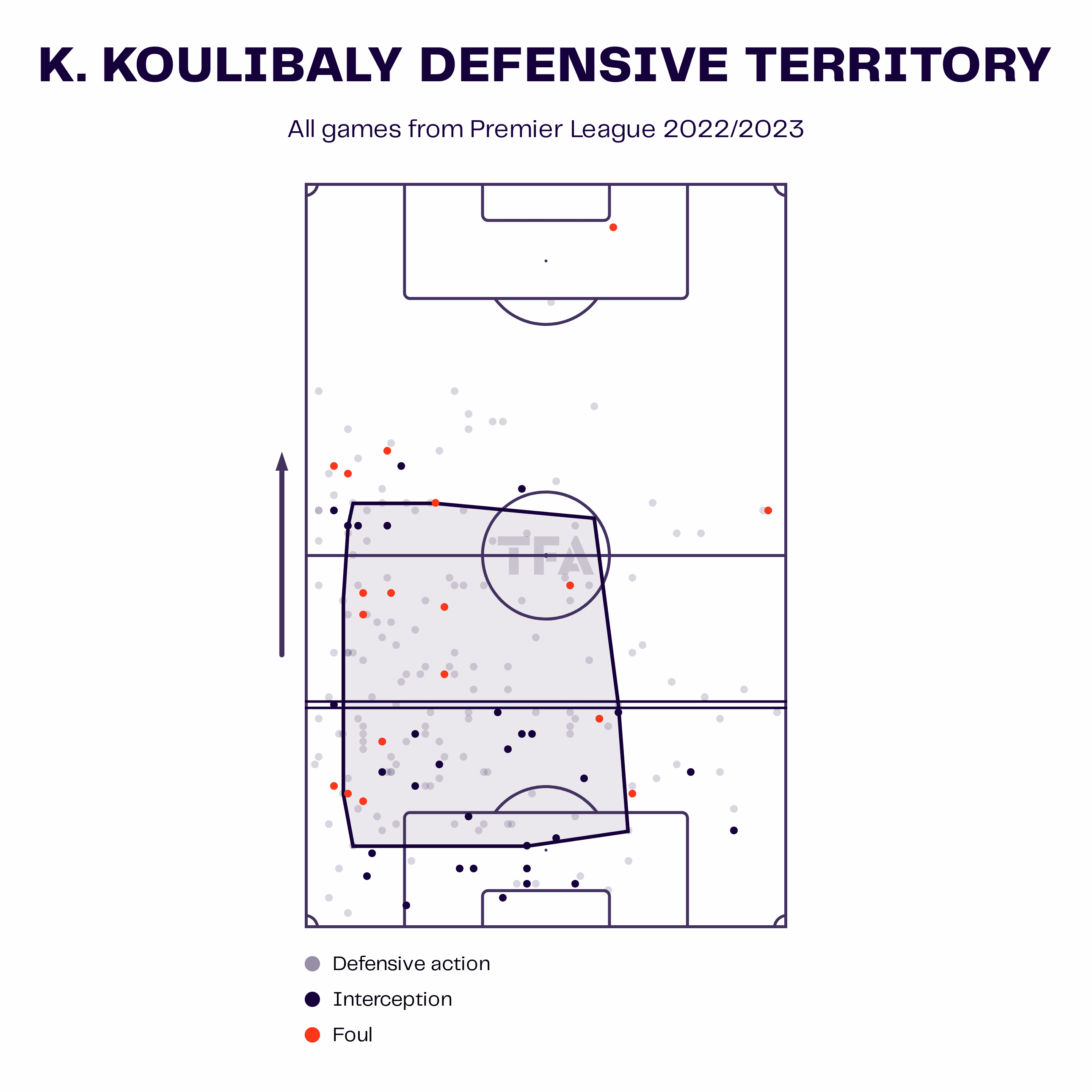

Koulibaly has had an interesting time of it too. He is playing reasonably well, but leaving a long-term stay at Napoli to join Tuchel put him in a position where he had to adapt to playing in a back three. The German’s firing led to Graham Potter’s hire which has brought about the return of a back four. Two managers, two systems, two positions and a brand new team is a heck of an adjustment in just six months.

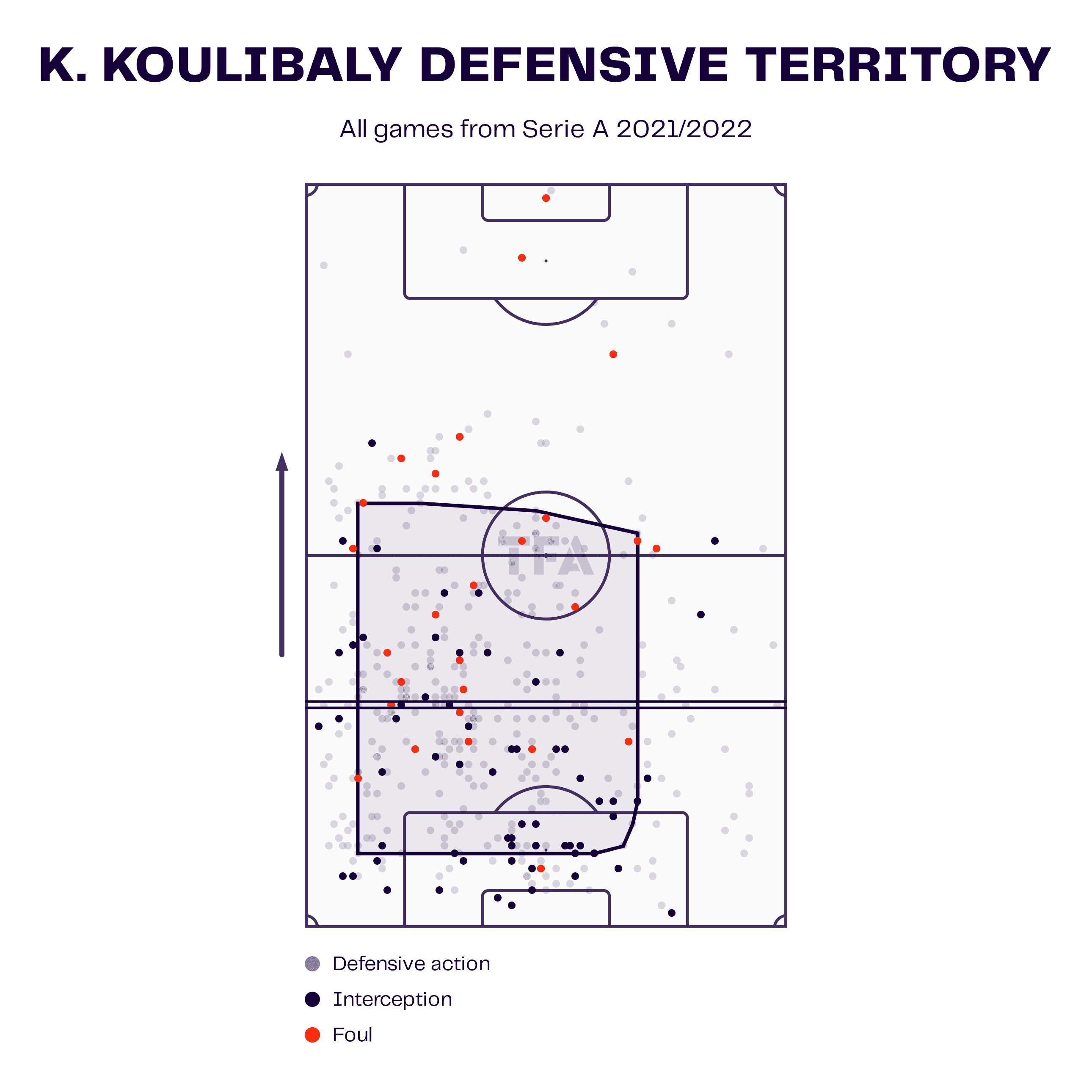

The typical area Koulibaly is covering hasn’t changed much. He is still a left central defender, but he has seen some changes from last season to his time at Chelsea.

Comparing his defensive territory maps from 2021/22 at Napoli versus 2022/23 with Chelsea, he still operates in the same part of the pitch, but he hasn’t seen the same level of involvement, especially in the box and the left half-space.

Though neither player has been poor with their new club, it’s safe to say they haven’t met the lofty expectations that were present when they sign the new deals. Both are having good seasons, but changing clubs, game models and systems takes time to fully adapt. Rüdiger is looking more comfortable in recent games and the return to a back four stands to benefit Chelsea’s Senegalese centre-back.

We’re really just scratching the surface in this analysis. We’ve talked about individual players who have moved to new teams, but we haven’t addressed the impact of centre-back pairings, especially the degree of comfort and understanding that’s necessary to play with a new teammate at the back. There’s also the perspective of new additions elsewhere on the pitch. For example, at Real Madrid, even if it’s a backline of Ferland Mendy, Alaba, Militão, and Dani Carvajal, Aurélien Tchouaméni has replaced Casemiro in the starting XI. That’s a whole other dynamic as to how the group influences how centre-backs manage the game.

Transfers along the forward line can influence the effectiveness of the high press, which then determines how much work the centre-backs must handle, but changes to the midfield and backline can trigger an adjustment for everyone, especially the centre-backs. They become accustomed to their teammates playing a specific way in front of them. Once the system is known, there’s an expectation that it is carried out consistently. When changes are made and tactics aren’t implemented at the same level, the centre-backs stand to suffer.

But that is part of the job. The best centre-backs will limit the adjustment by developing an understanding of how their new teammates play and bringing the new guys up to speed with their positional roles within the club’s game model.

Conclusion

Centre-backs and goalkeepers get fingers pointed at them often. Their job is a tough one with zero room for error. When mistakes are made consistently, whether by them or their teammates, their management of the game and their performances come under the microscope.

As one of the leaders on the team, a player like Virgil Van Dijk will surely take accountability for his team’s performances and understand how he can improve his own. Part of his job is to help the team as a whole play more effectively and carry out their positional responsibilities.

To put all the blame on him is foolish, but it does allude to that opening question on centre-back performances. When the team concedes goals, it’s the centre-backs and goalkeeper who come under question.

If anything, analysis of a centre-back’s performance cannot be dictated strictly by the number of goals the team is conceding or the scoring opportunities gifted to opponents. That’s the easiest way to measure performance at centre-back and goalkeeper, but it’s insufficient. A deeper dive into Van Dijk’s 2022/23 campaign, as well as looking into the scenarios surrounding Škriniar, Rüdiger and Koulibaly will shed some light on this topic. Assessing a centre-back is a multi-dimensional scouting project. There is a team performance aspect to it, as well as looking into the individual numbers. New managers, game models, systems and teammates will also play a role in a centre-back’s effectiveness.

The deepest field player requires a deeper scouting report. Van Dijk’s talent and influence are still there. Liverpool has some issues to sort out, but the big Dutchman is one of the players to lean on to get them out of this mess.

Comments