I wish to begin by thanking manager Dominik Glawogger and assistant manager Christian Dobrick for the many ways in which they supported the creation of this tactical analysis piece.

Holstein Kiel U19s have demonstrated a variety of possessional principles this season under manager Dominik Glawogger and assistant managers Christian Dobrick and Freddy Kaps. These principles that Holstein exhibit revolve around brave possession to play through opposition pressure in order to progress the ball up the pitch and arrive in space in dangerous positions. In this piece of tactical analysis, we will look at what these principles and philosophies are, and how they combine and influence one another to allow Holstein to create chances.

Holstein Kiel’s overarching principle in possession is to play out from the back, when in possession, in order to allow them to execute their own personalised principles of play. The first action of building up in possession begins in the first phase with the keeper.

Inviting the opposition to press

Holstein see possession as a tool to progress the ball rather than being an objective in itself. What this means is that possession in front of the opposition or without the intent to manipulate the opposition’s defensive structure is meaningless. Instead, it should be seen as a means to consistently find players in more advanced positions to be able to receive the ball in space in areas that are favourable to create good goal scoring opportunities. As a result, Glawogger prefers not to have his side build up with numerical superiority against the opposition’s first line of pressure, unlike many teams to which this is common practice. The reasoning behind this is that having numerical superiority in this area forces the opposition’s first line of pressure to drop deeper, since pressing whilst outnumbered is seldom effective. Whilst it would allow the team in possession to comfortably keep the ball in the first phase of build-up, it would conform to the notion of possession being an objective rather than a tool. The opponent’s first line of pressure dropping off would decrease the amount of space available further up the pitch as the opposition are now more compact, thus inhibiting the effectiveness of possession as a tool to progress up the pitch.

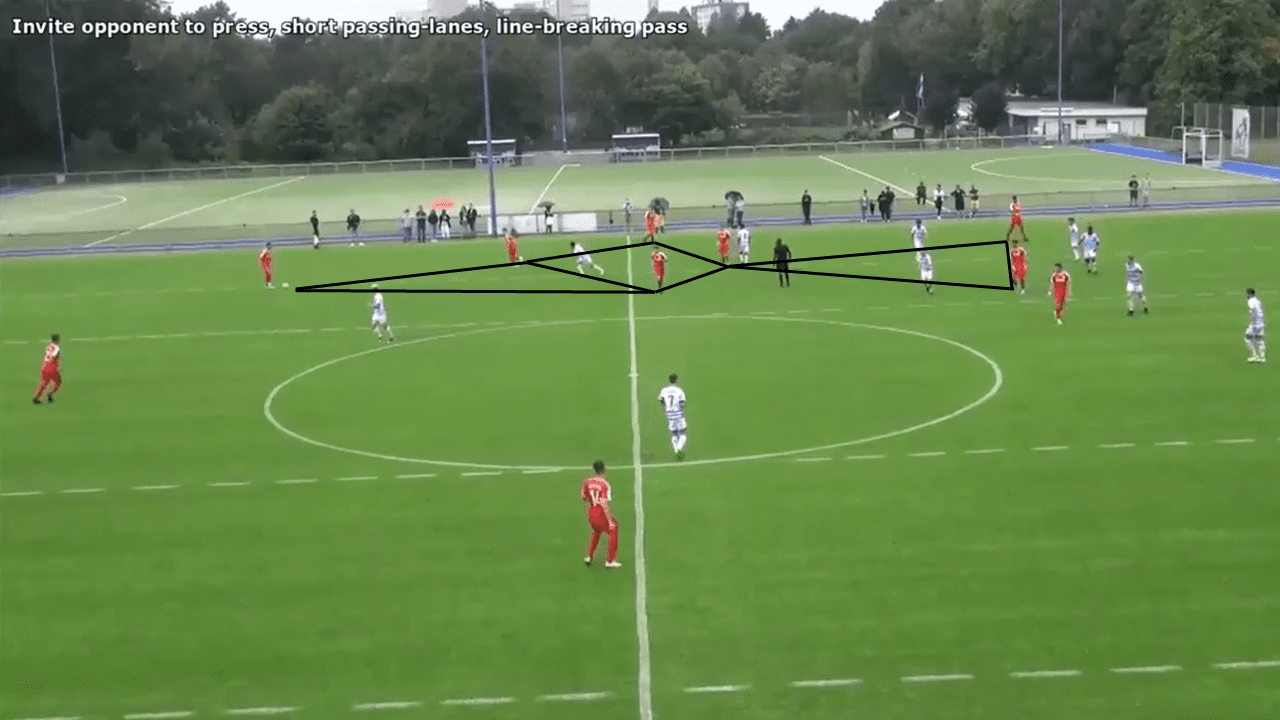

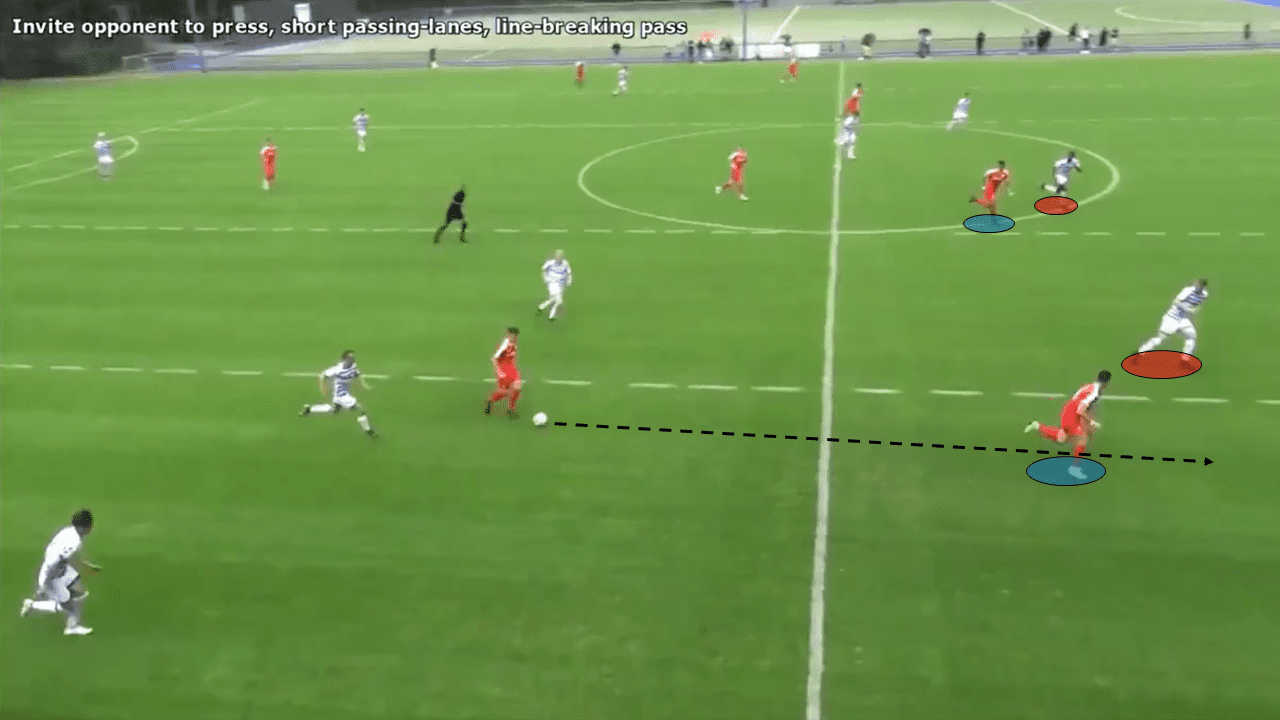

Instead of building up with numerical superiority in the first phase, Glawogger, therefore, prefers to build up with numerical inferiority; this essentially forms an “offensive pressing trap”. Holstein utilise this numerical inferiority to create an environment in the first phase of build-up that appears easy for the opposition to press. Engaging the first line of pressure vertically stretches the opponent’s defensive structure, creating space to receive in behind the first line of opponents.

In the example above, Dynamo Dresden have a 3v2 advantage against Holstein’s centre-backs, exhibiting Holstein’s conscious effort to build up with numerical inferiority. However, Dynamo’s first line committing to the press has opened up space behind them that can be exploited by movement from Holstein’s midfield players to receive.

Furthermore, if the opposition decide not to press, Holstein can build up without pressure. A key advantage of building up with numerical inferiority in the first phase of possession is that it allows for numerical superiority in the midfield area of the pitch. Therefore, if the opposition’s first line of pressure doesn’t close down Holstein’s centre-backs, they are free to pick a pass into a midfielder, as their superiority in the midfield zone will always allow for the possibility of a free player.

High positioning of the midfield to create space behind the first line of pressure

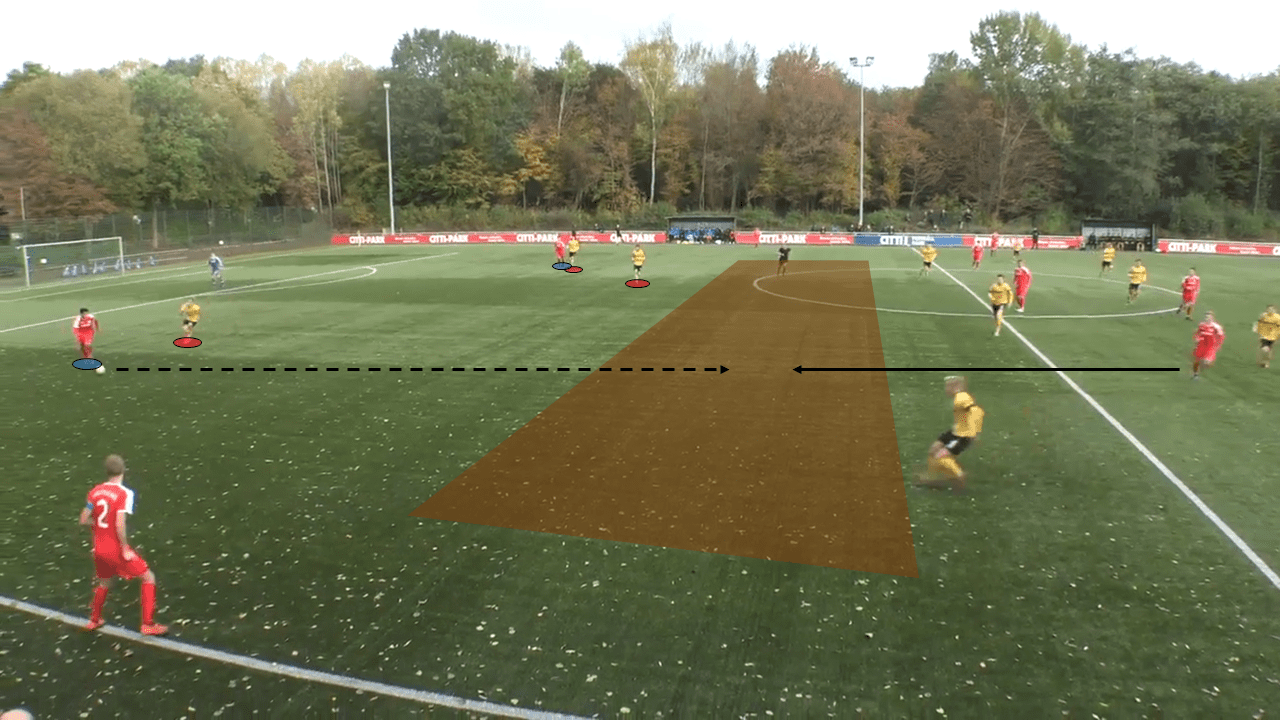

In order to make the most of this space created behind the first line of opposition pressure, Holstein’s tactics are to initially position their midfield further up the pitch, closer to their attackers. The intention of this is to force the opposition’s second line in their defensive structure to drop deep, thereby enhancing the space behind the first line of pressure.

In the above instance, Hamburger SV are drawn into the offensive trap that Holstein have set, while Holstein’s midfield stays right up close to the halfway line. As a result of this, a significant amount of space is created in the gap between Hamburg’s first and second line of pressure.

How Holstein utilise the space created by the offensive pressing trap

Holstein prefer to receive while arriving into space. If their players were to stand in the space behind the opposition’s first line of press, an opponent can easily see them in space and step out to mark them. By the time they have received the ball, they are no longer in space. This is where an essential part of Holstein’s build-up comes into play: dynamism. Instead of receiving in a static state, Holstein’s players will receive the ball while arriving into space they know is available. The result of this is that the receiving player now has time and space. An opposition player might then try to step up to the receiving player to close their space, but that opens up additional space in the area they just vacated. This is why Holstein’s opponents are forced to constantly adapt their defensive structure to the movements of the Holstein players off the ball.

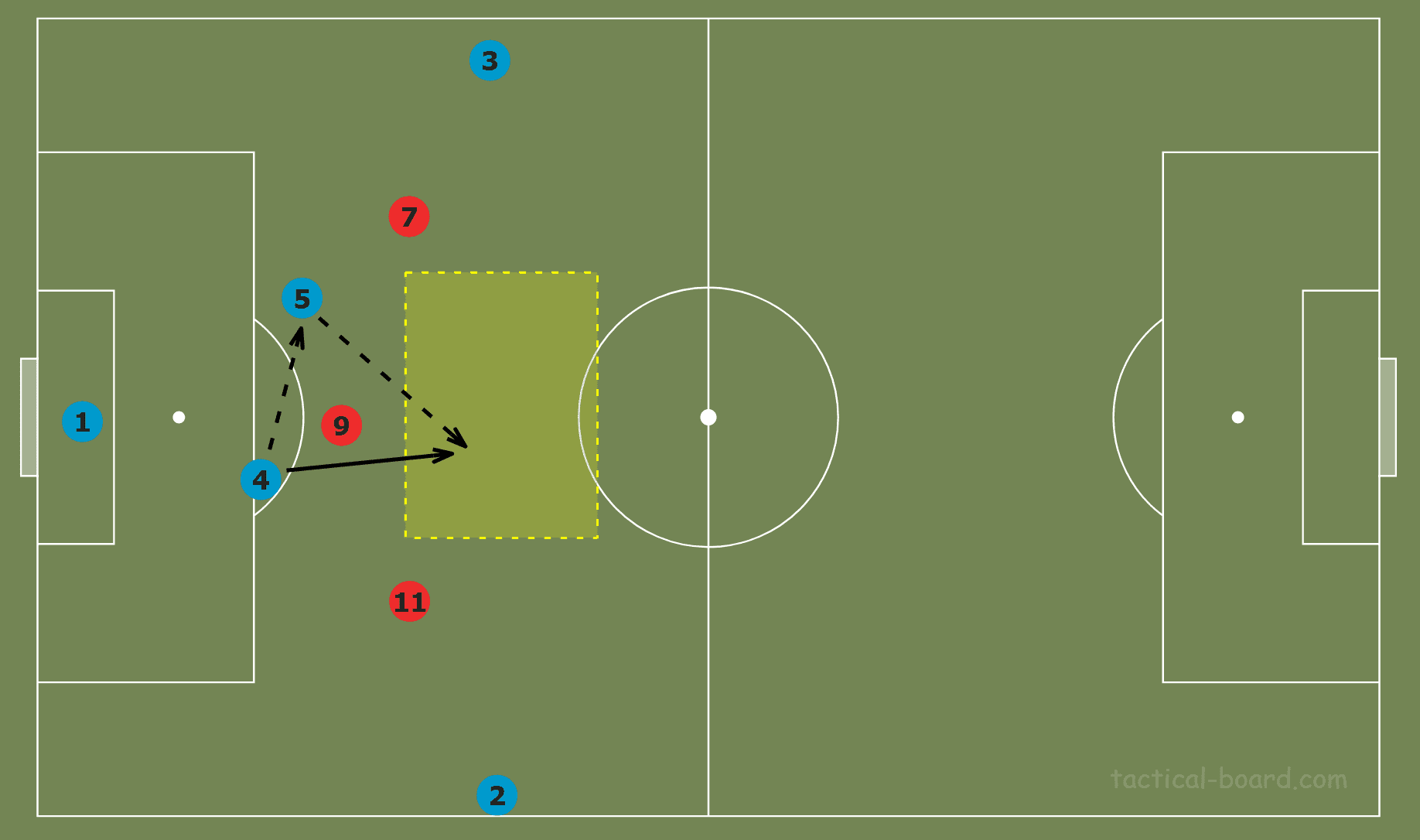

One strategy that Holstein use to find a free man arriving in space is through give-and-go combinations.

The graphic above displays how two centre-backs can combine to receive behind the line of pressure. The first movement comes from the number four who initially drops slightly deeper. The intention of this movement is to draw the opponent pressing him out to create space behind him. Once the space has been created, the number four passes to the number five immediately before making a vertical run into the space behind. The number five plays a one-touch lay-off pass, and the number four now has possession behind the first line of pressure. While this combination is often used by teams’ attackers to get in behind the opposition’s backline, Holstein are brave enough in possession to use this technique in the first phase to play through the opponent’s press.

In the above example, we see Holstein’s right-back drop to receive a pass from the goalkeeper. As he does so, a Dynamo player steps out from his position in the defensive structure to press him. After playing a pass down the line, he immediately makes a run into the space behind the Dynamo midfielder that has just stepped up to press.

The Holstein player can then play a quick lay-off pass into the path of the right-back running into the space from deep, who is now in space with the ball behind Dynamo’s midfield.

Give-and-go combinations are not restricted to Holstein’s outfield players. When being pressed in their own box, Holstein’s keeper is not afraid to draw a player in before playing a give-and-go in the same manner as previously demonstrated. In fact, since players are more likely to fully commit to pressing the keeper as they don’t expect the keeper to make a run behind them, it can actually be even more effective due to the element of surprise.

The give-and-go method is an example of how Holstein create positional superiority in order to play through opposition pressure. This leads to a more general principle of Holstein’s play, which focuses on the idea of positional superiority, named “dynamic space occupation”.

Dynamic space occupation

Holstein’s principles in possession revolve around the philosophy of positional fluidity, similar in concept to the famous “Total Football”. Holstein do not see the idea of a fixed structure in possession, one where players’ movements are limited to a confined zone, to be of use. The movements that Glawogger wants from his team would only be restricted by keeping players fixed in position. We have already seen the importance of this in the discussion of give-and-go combinations; the right-back was able to advance in-field to make use of created space, which was only possible through an atypical movement to that of a right-back.

While being true to a position isn’t a necessary part of Holstein’s build-up, what is positionally important is space occupation, which is also one of the key principles of positional play. This concept is vital in order to successfully create space on both a macro and micro-level. An example of its importance on a macro-level could be something as simple as maintaining width in offensive structure. Play too narrow and the opposition can defend narrowly compact, therefore space within their structure will be very limited so ball progression becomes challenging. Its importance on a micro-level involves occupation of certain areas on a pitch in order to enable the creation of space through movements. When one player moves out of their “position”, it is important that the area they vacated is then occupied by another teammate. If a large area of the field becomes unoccupied without an intention to receive in, then that space created by one player dragging an opponent out of position becomes meaningless. In fact, for this reason, a team that leaves large spaces without the intention to receive in may find it harder to progress the ball than a team that is close to static but occupies all areas of the pitch in possession.

The combination of Holstein’s principles of space occupation and positional fluidity creates the concept of dynamic space occupation: this is key in manufacturing situations of positional superiority.

Using dynamic space occupation to create positional superiorities

Holstein players are required to be spatially intelligent. Their principle of positional fluidity allows them to make movements into areas of the pitch a player of their position would not usually occupy. Since space entirely depends on the exact positioning of the opposition players, Holstein’s players possess the freedom to identify space and make decisions on when to move into space to receive. However, it is important when moving into space to also be able to form passing lanes.

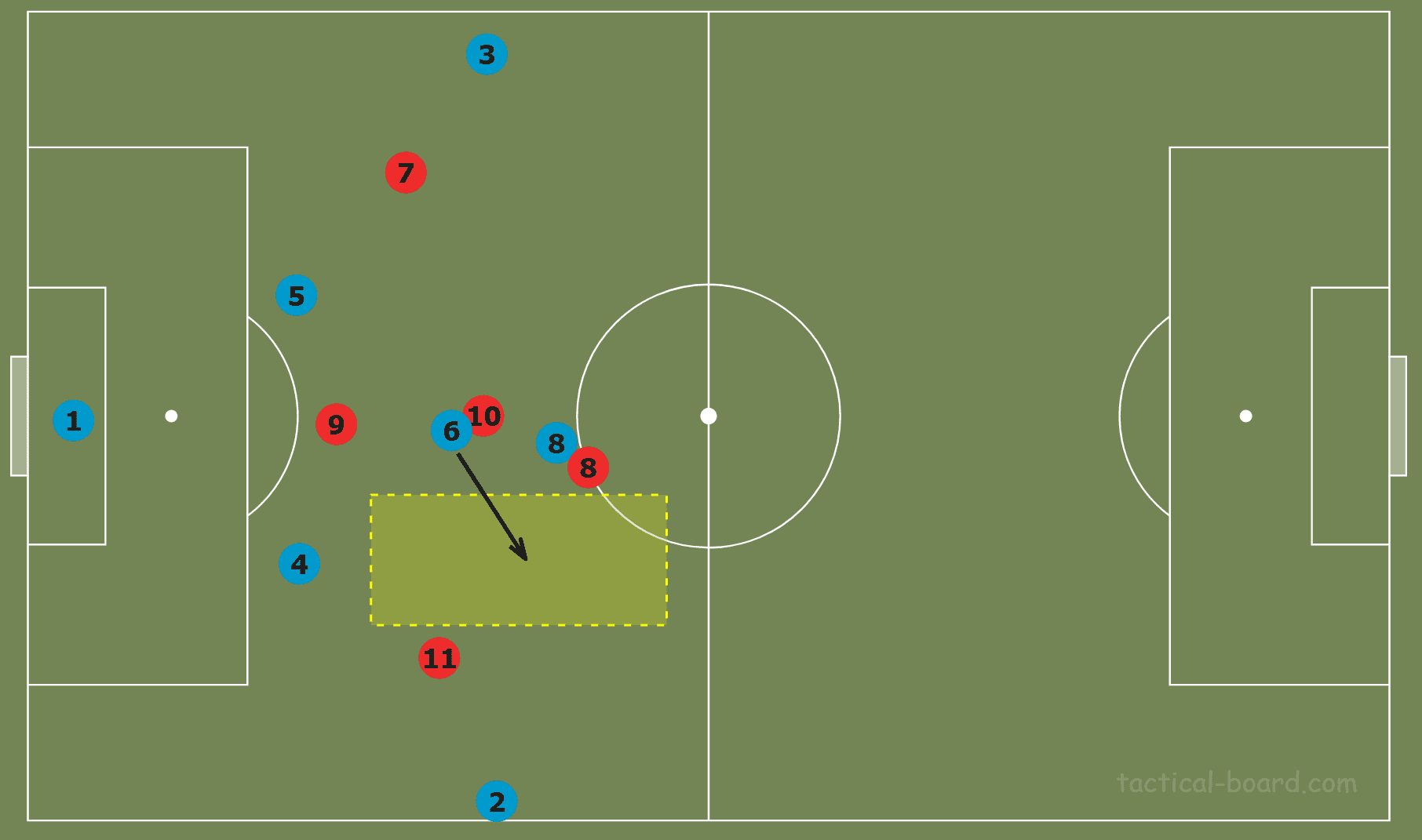

Holstein players use rotations to manipulate the opposition defensive structure to create positional superiorities that allow them to receive in space. However, dynamic space occupation is a key part in how Holstein are able to form these superiorities. The first movement occurs by a player who is in a state of being marked but sees available space in which they could receive a pass; this can be a lateral, diagonal, or vertical movement. Once the Holstein player has made the movement into the space, dynamic space occupation becomes important in order to create a passing lane to a free player. To prevent the player’s marker from simply following him into the space, a nearby Holstein player will move into the area that his teammate just vacated. This creates a dilemma for the opposition player of whether to follow the playing moving into space or to mark the player entering the space that the other Holstein player just vacated. This is how positional superiorities are created: Holstein create dilemmas for the opposition through dynamism, or in other words, a combination of movements designed to manipulate the opposition.

Let’s take a look at an example.

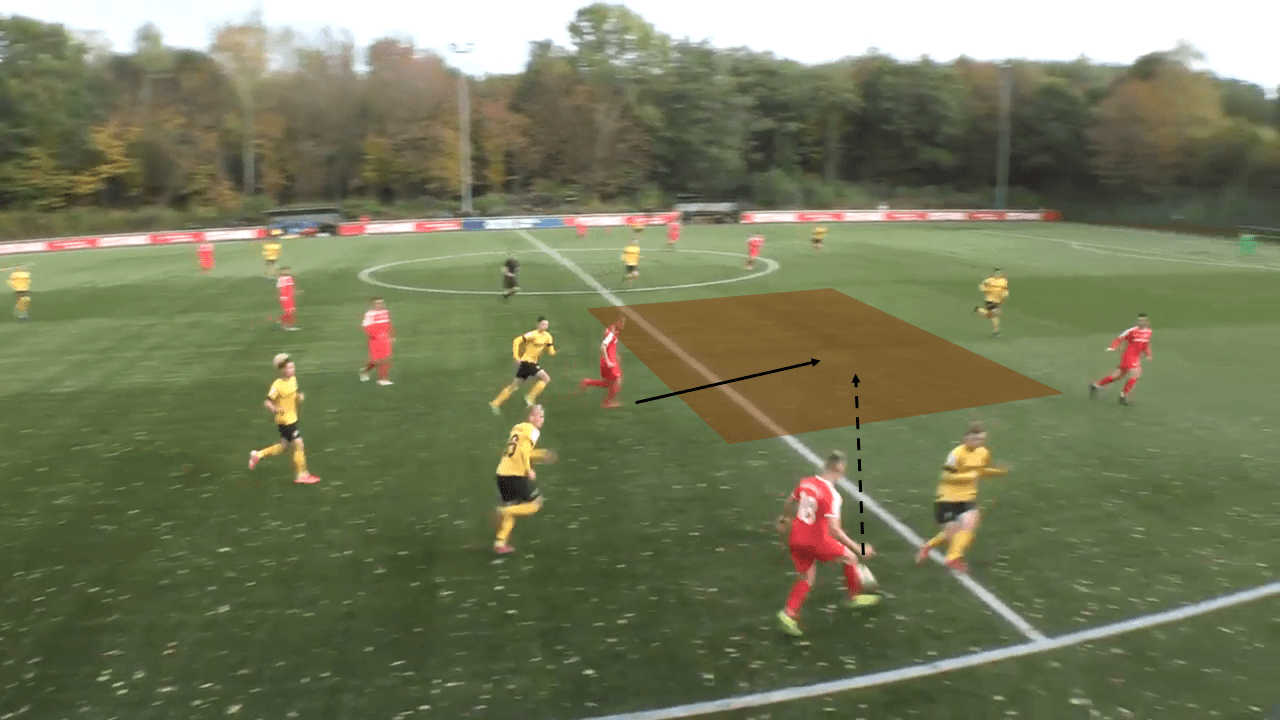

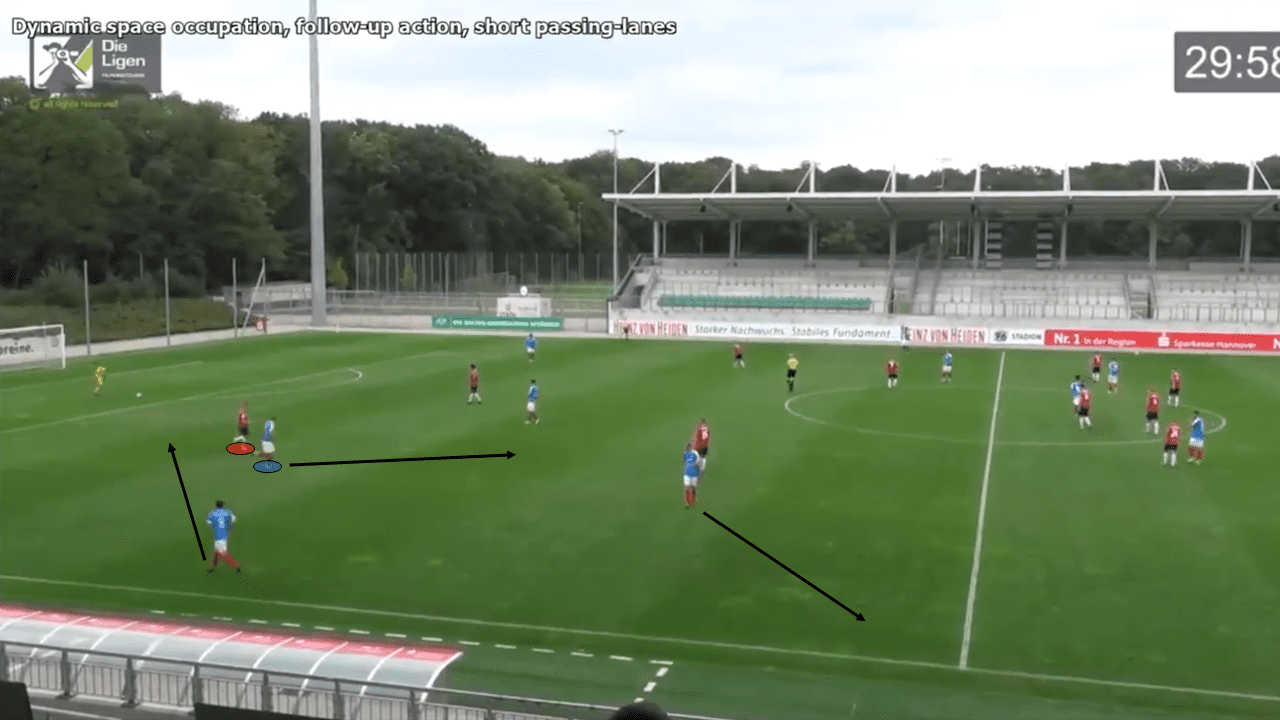

Here, the Holstein centre-back receives the ball with an opposition player pressing him. The only option he has is to pass to his goalkeeper. However, he recognises that there is space behind the first line of pressure. As soon as he plays the pass to the goalkeeper, he makes a run into the space.

The player who just pressed him begins to track his movement. But, as he makes that diagonal movement, Holstein’s fullback makes a movement into the space the centre-back is vacating. This causes a problem for the opposition player, as he now must decide whether to follow the centre-back in-field, or whether to mark the fullback who is coming inside. Seeing the fullback come inside, another Holstein midfielder moves out to the flank to maintain the width, thereby displaying efficient space occupation.

The opposition player decides to stop following the centre-back, unwilling to leave a large space for the fullback to receive in. As a result, the centre-back is free to receive a pass from the goalkeeper behind the first line of pressure. Holstein’s holding midfielder (also highlighted) sees the centre-back move towards his space, so moves laterally towards the far side to provide a second passing lane behind the first line of pressure from the keeper. This additional movement means that the opposition player marking the holding midfielder now cannot keep the holding midfielder in his cover-shadow, as pressing from that angle would leave too big a gap between him and the left-winger for Holstein’s keeper to play the ball through.

While these movements are specific to each situation as they are dependent on the exact positioning of the opposition, certain conceptual patterns of movements can be applied in a variety of situations. An example of this would be positional rotations between players, which is possible due to the positional freedom of each player. Positional rotations involve the “swapping” of positions of two players in order to manipulate opposition defenders to find a free man in space.

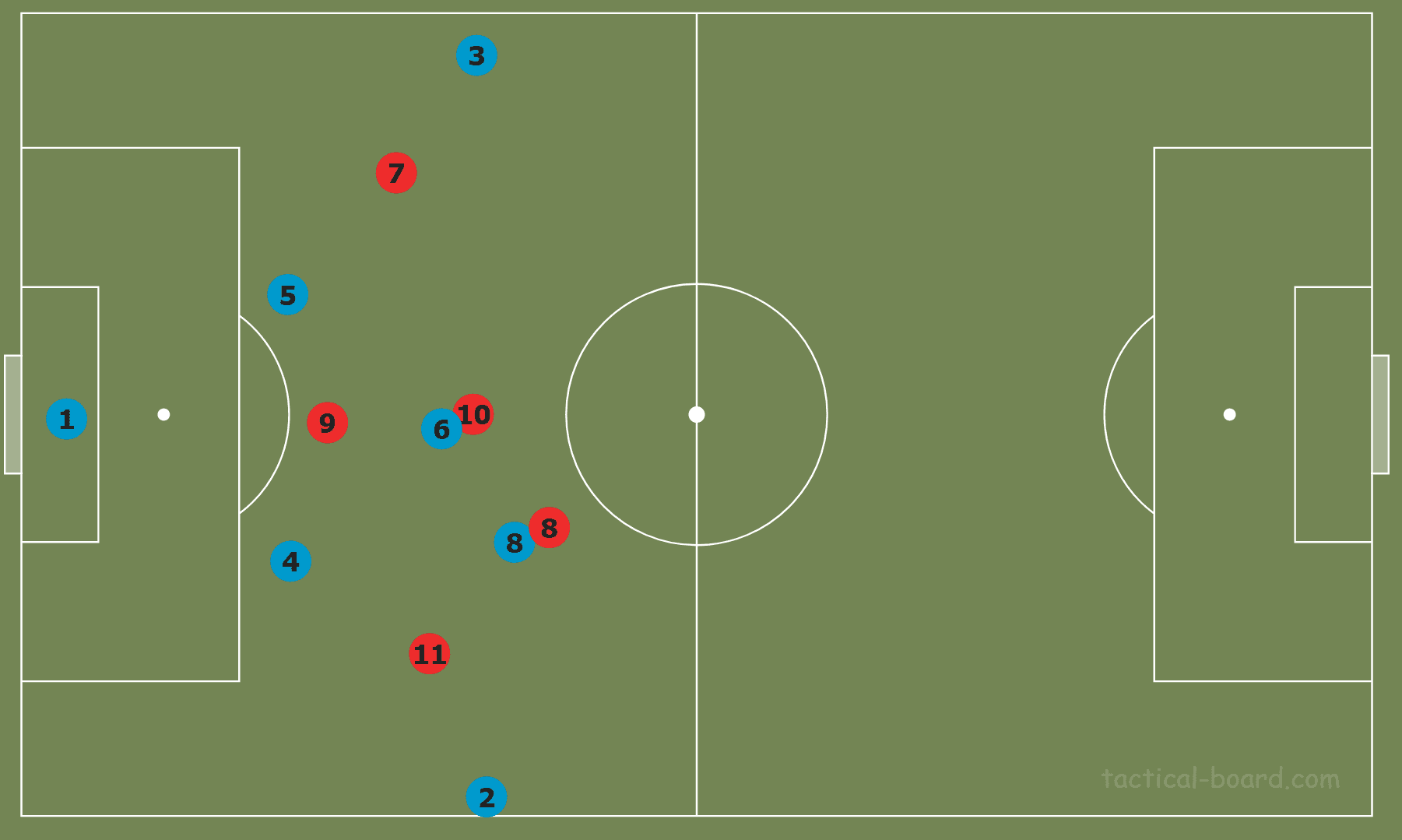

This graphic shows two midfielders being marked tightly by two opposition midfielders.

This pattern of positional rotation is initiated by the number eight, who moves in-field towards the number six. To prevent a 2v1 situation on red’s 10, the red number eight must follow blue eight. This opens up space in the area that was vacated for number six to move into and receive a pass. This second movement from the number six is vital to exploit the space.

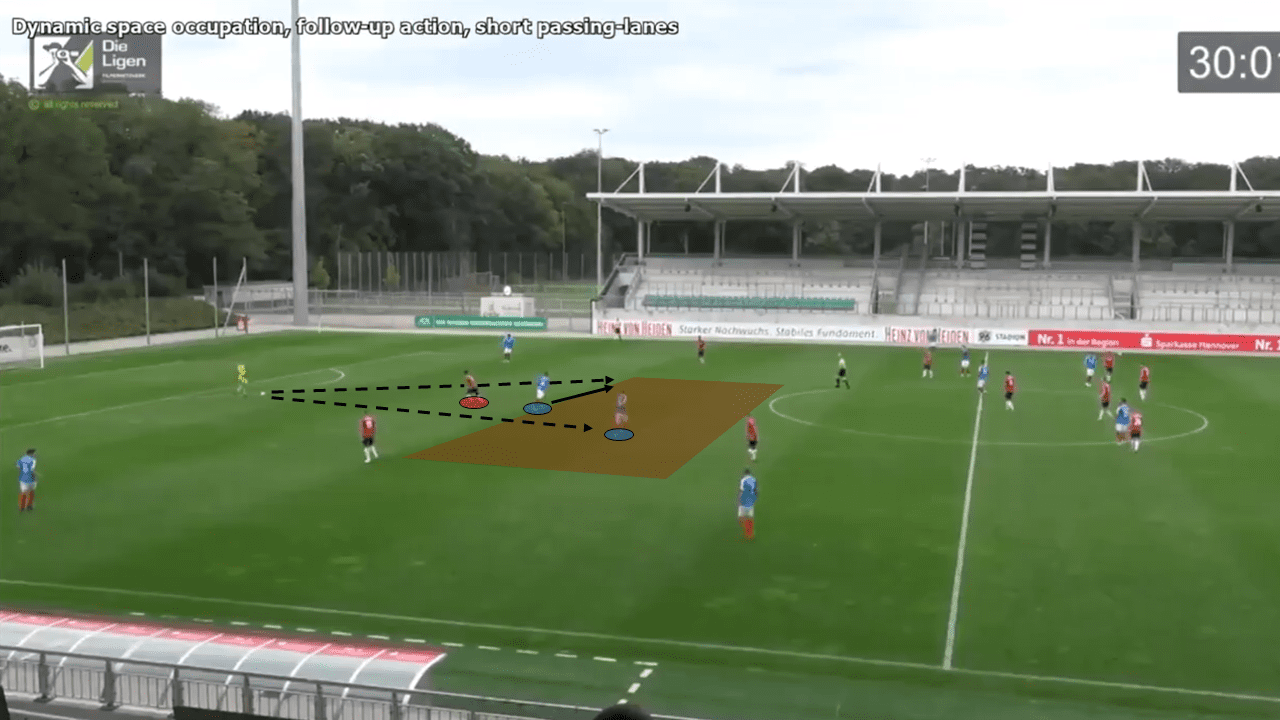

Here is an example of Holstein using positional rotations to create space to receive in. One Holstein midfielder drops deep, dragging his marker and freeing up space behind him.

A pass is then fired into the feet of a different Holstein player who is now able to carry the ball into the space behind Dynamo’s midfield line.

Arriving in the final third

We have already discussed how Holstein underload in the first phase of possession to create an offensive pressing trap to stretch the opposition’s structure vertically. However, they also stretch the structure horizontally by overloading one side and underloading the other. The idea of this is to lure the opposition into pressing aggressively on the side of the pitch that they are overloading, before switching the play into the space on the other side of the pitch. This technique is particularly useful at arriving into the final third in space.

The positional freedom of the Holstein players allows them to shift to one side of the pitch if there is potential for an overload. Doing so creates a dilemma for the opposition. Either they can remain zonal in order to not leave space on the far side, or they can commit more defenders to the overloaded side of the pitch to try and cope with the increase in number of Holstein players. If they choose the former, Holstein will have numerical superiority on the side of the pitch they have overloaded so can easily play through the opposition, and if they choose the latter, Holstein can switch play to the opposite flank and take advantage of the large amount of space available to them on the underloaded side.

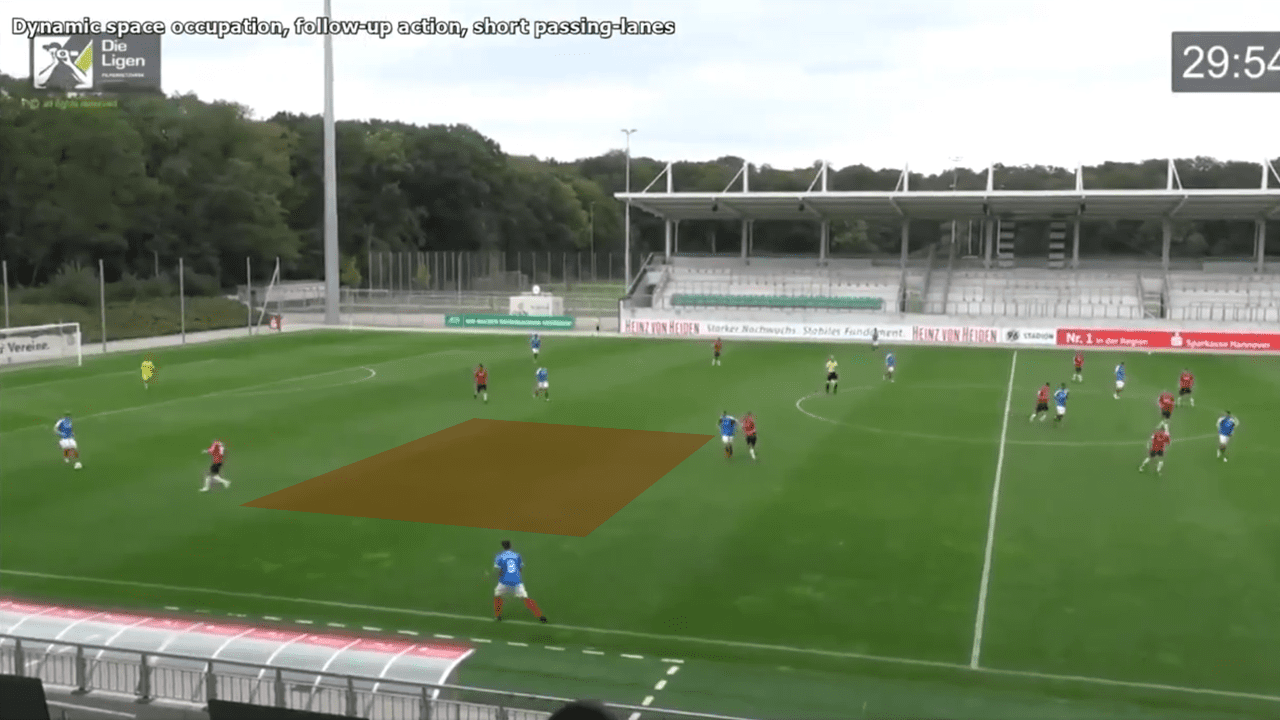

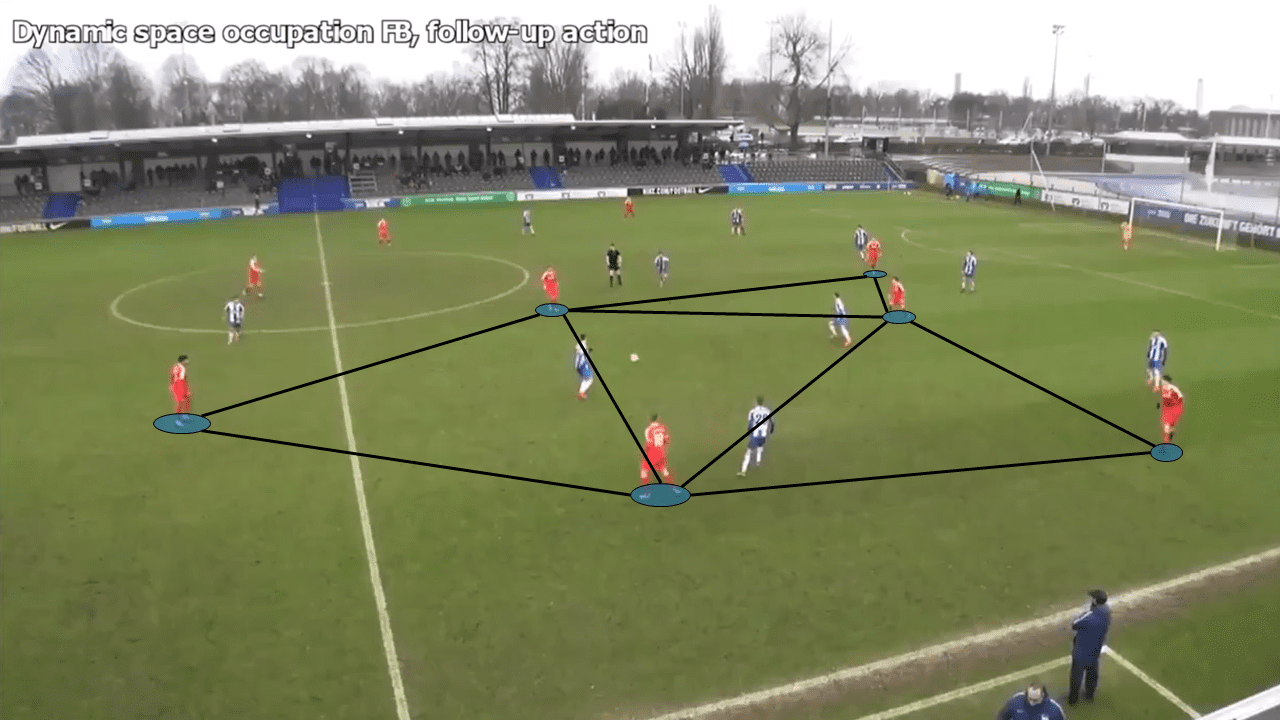

The image above exhibits Holstein’s use of key positional play principles while overloading the ball-near side. The importance of the formation of triangles in these situations is reflected in Holstein’s play. Creating a web of triangles allows for as many passing lanes as possible, forcing the opposition to commit even more players to this side thus opening up greater amounts of space on the far side of the pitch.

In these situations, dynamic space occupation is still important to open up space, as this creates space for players to receive in and play passes laterally into space on the underloaded side.

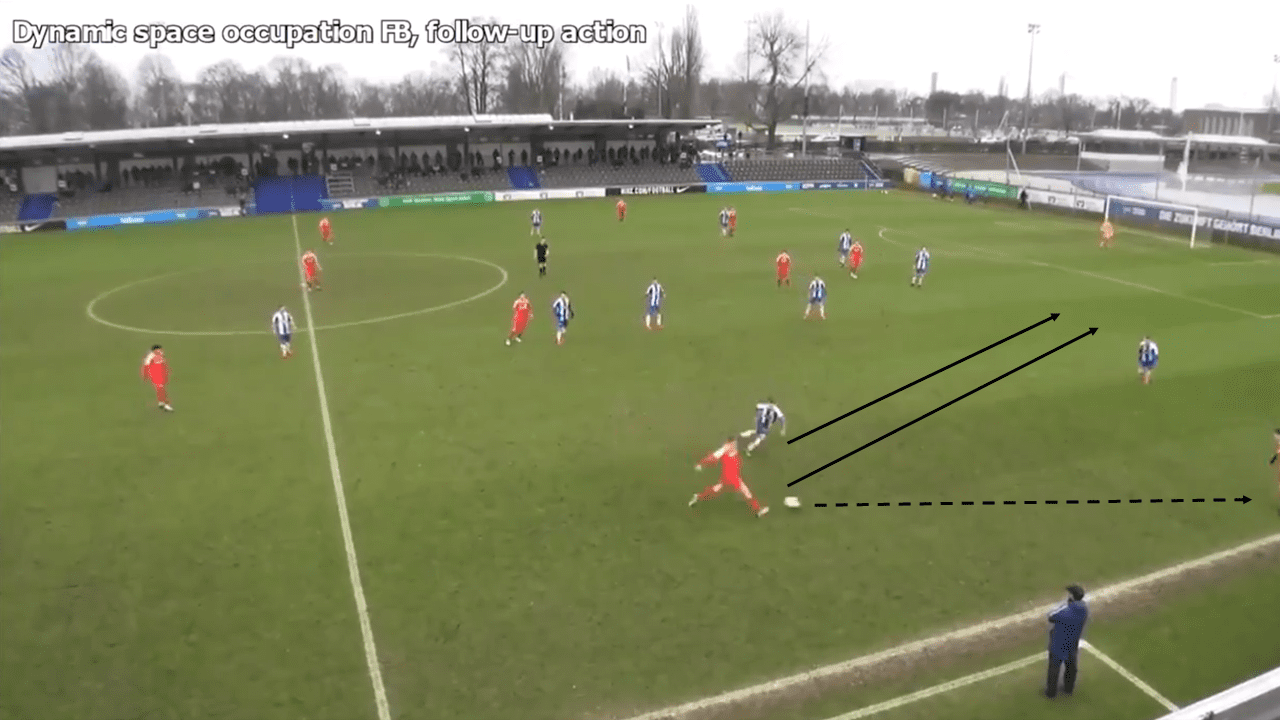

Here, straight after playing a pass into the wide forward, the Holstein fullback makes a run into the space behind the opposition fullback, forcing his marker to leave his space in the defensive structure to track his run.

This movement allows the wide forward to cut inside and carry the ball into the space created by the inside run of the fullback.

From the above position, the wide forward can then play a pass into either teammate on the far side of the pitch, the side they chose to underload. Since the overload successfully dragged the opposition to the ball-near side, Holstein were able to create a 2v1 situation on the opposition fullback.

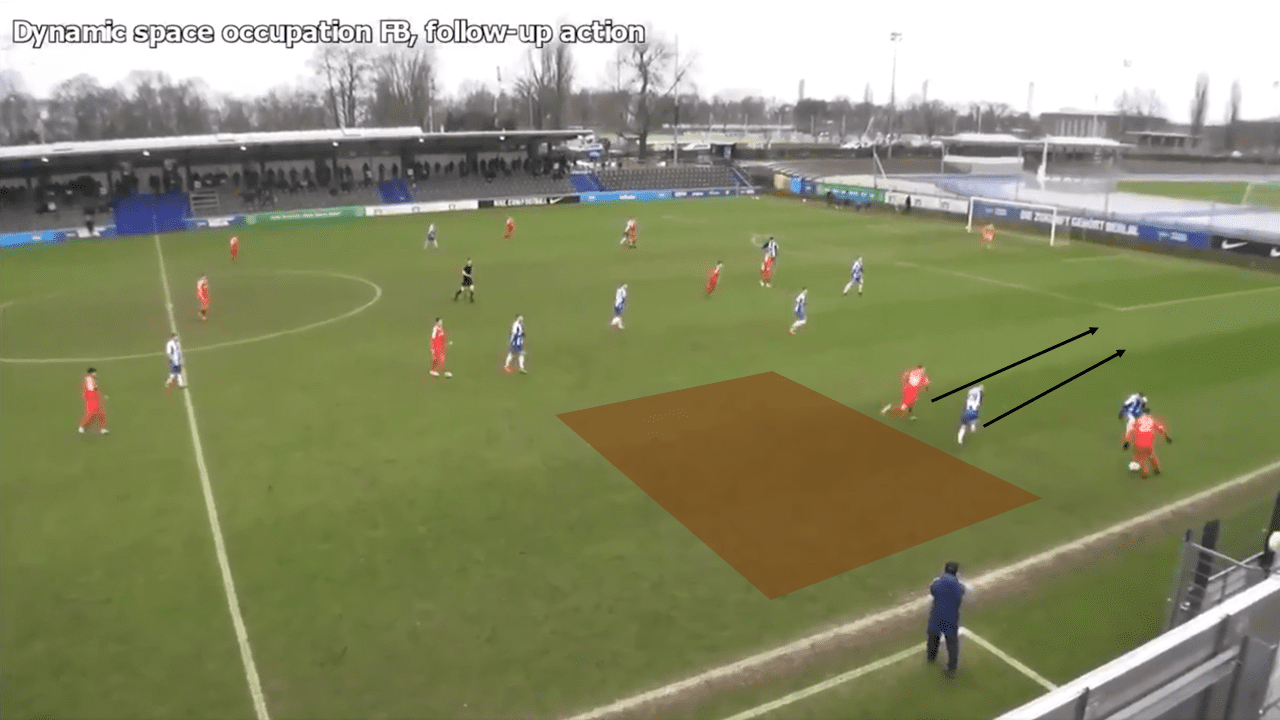

In the above example, we see Holstein overload one side of the pitch, making sure to again support the player in possession with multiple passing options.

The ball is kept on that side until an opportunity to switch play has opened up. In this instance, the keeper is able to play a diagonal to the ball-far fullback who is able to receive in space.

One of the Holstein midfielders is then able to receive in the inside channel in an abundance of space after making a movement to the underloaded side of the pitch.

The midfielder can turn and play a pass into the wide forward who is now 1v1 against the opposition fullback. This space that has been created on the underloaded side has shown how favourable 1v1 and 2v2 situations are, like the one demonstrated above, can be created, as the rest of the defending team is not close enough to shift over to provide support to the rest of the defence. These open spaces are far more efficient areas to create chances from, since the opposition defenders are isolated against Holstein’s attackers.

Conclusion

To conclude this analysis piece, Holstein Kiel U19s exhibit numerous complex principles and tactics that interact with each other to create a game model that enables them to consistently progress the ball into advanced areas of the pitch in possession. These principles all contribute to the key notion of utilising possession as a tool rather than possession for possession’s sake. Furthermore, dynamic movements are the vital element in allowing Holstein to manufacture situations where they possess positional superiority and can, therefore, play through the opposition.

Comments