When Johan Cruyff became Barcelona’s manager in 1988, he spearheaded a revolution at the Catalan club in several ways, none more significant than his impact on the club’s famed ‘La Masia’ youth academy.

Cruyff’s vision for La Masia, from his intent to use the club’s youth system extensively to his demands on what kinds of players would be recruited to the academy altered La Blaugrana’s history, acting as a key catalyst for their evolution into the club we recognise today with their distinct style of play and, concurrently, the types of players that have become legends at Camp Nou, from Pep Guardiola to Xavi, Andrés Iniesta and, of course, Lionel Messi.

At 182cm tall, Óscar García is a La Masia graduate who advanced to Barca’s first team during the Cruyff era and would’ve still made the cut with the minimum height limit prior to the Cruyff-led academy overhaul.

However, it’s evident that the now-49-year-old manager learned a key lesson from the Dutch legend whom he played under, which was the importance of the coach stamping their authority on the club’s youth academy and ensuring this natural resource is used exactly as they want, to supplement their work with the first team.

After García took charge of Ligue 1 Reims, the Sabadell-born coach directed an overhaul of his new club’s youth system and shoved Les Rouges et Blancs into an era in which they present a clear pathway from academy to first team which, last season, saw Hugo Ekitiké rise to stardom, leading to a significant sale to PSG where he now calls himself a teammate of the aforementioned Messi, resulting in a healthy windfall for Reims in the process — highlighting one potential benefit of this academy-reliant approach to managing the first team.

Another lesson García learned from ‘El Salvador’ during his time playing under the visionary coach at Barcelona was, in his words from a recent interview with The Guardian: “you can change a lot of things but you can’t change the philosophy.”

In that same interview, García shed some light on his managerial philosophy, explaining: “I like to develop players while being really competitive” while discussing his open approach to using players from Reims’ youth academy before going on to elucidate that, for him, the specific system of play “always depends on your squad” and “only the players know how we are going to play”.

So, the former Brighton & Hove Albion, Watford, Saint-Étienne, Olympiacos and Red Bull Salzburg (among others, again, at just 49 years of age) coach evidently believes in sticking to a clear philosophy but not one concerning style of play or systems, rather one that emphasizes the existence of a clear pathway from academy to first team and relies heavily on youth players while “being really competitive”.

It’s, of course, difficult to achieve maximum success with inexperienced players yet to reach their prime. Still, young players have benefits too, with Sir Alex Ferguson famously relying on youth throughout his decorated Manchester United tenure. It’s been said that Ferguson valued the fearlessness that often came with youth and perhaps this, along with the increased opportunity to mould a player in his image and help them grow into a greater asset, is something García values too.

In any event, García guided a Reims side that boasted the youngest average age (24.2) in France’s top flight last season to a respectable 12th-place finish while developing Ekitiké from an unknown into one of France’s hottest commodities last term — not a bad first season at Stade Auguste-Delaune. Reims still have the youngest squad in Ligue 1 this season (23.7) and sit in 16th place on the table, at the time of writing.

So, how is García attempting to make his non-negotiable philosophy work at the Ligue 1 side? This tactical analysis piece aims to provide some insight into the 49-year-old’s tactics at Reims via analysis of his team’s performance this season so far and over the entirety of the previous campaign. We’ll look at some key tactical components of the Catalan coach’s Reims side to highlight what he’s doing to get the absolute most out of his young team.

Verticality in possession

Despite the major Cruyff influence, García’s team is not heavily possession-based in the slightest. In fact, Reims ended last season with the second-lowest average possession percentage (42.9%) in Ligue 1, while they’ve currently got the lowest average possession percentage (38.7%) this term.

Reims also ended last season with the lowest passing rate (13.2 passes per minute of possession) in Ligue 1, while they’ve currently got the second-lowest passing rate (13.1 passes per minute of possession) in France’s top-flight for 2022/23.

García’s side is extremely comfortable playing very direct and vertical in possession, with Reims often aiming to get the ball upfield quickly, either finding a player in space who can take the ball down, turn, drive forward and link up with an attacking teammate or winning the second ball after sending it long upfield — with both situations designed to quickly put the opposition’s backline under pressure before the opponent really has time to organise themselves in a settled defensive shape.

It’s common to see Reims go long directly from a goal-kick, aiming for one of their forwards or even the number ‘10’ if they’re utilising one at that time, with García having primarily utilised a 3-4-1-2 shape this term, but also having regularly used a 3-4-3 and 3-5-2 over the last calendar year.

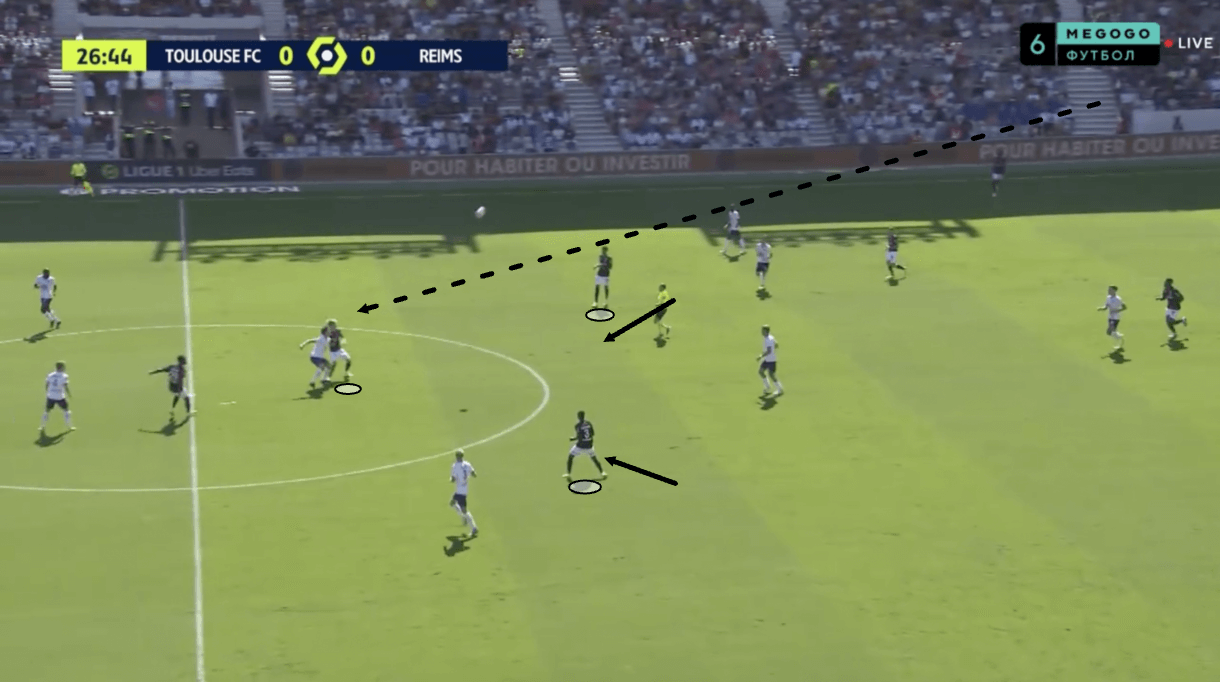

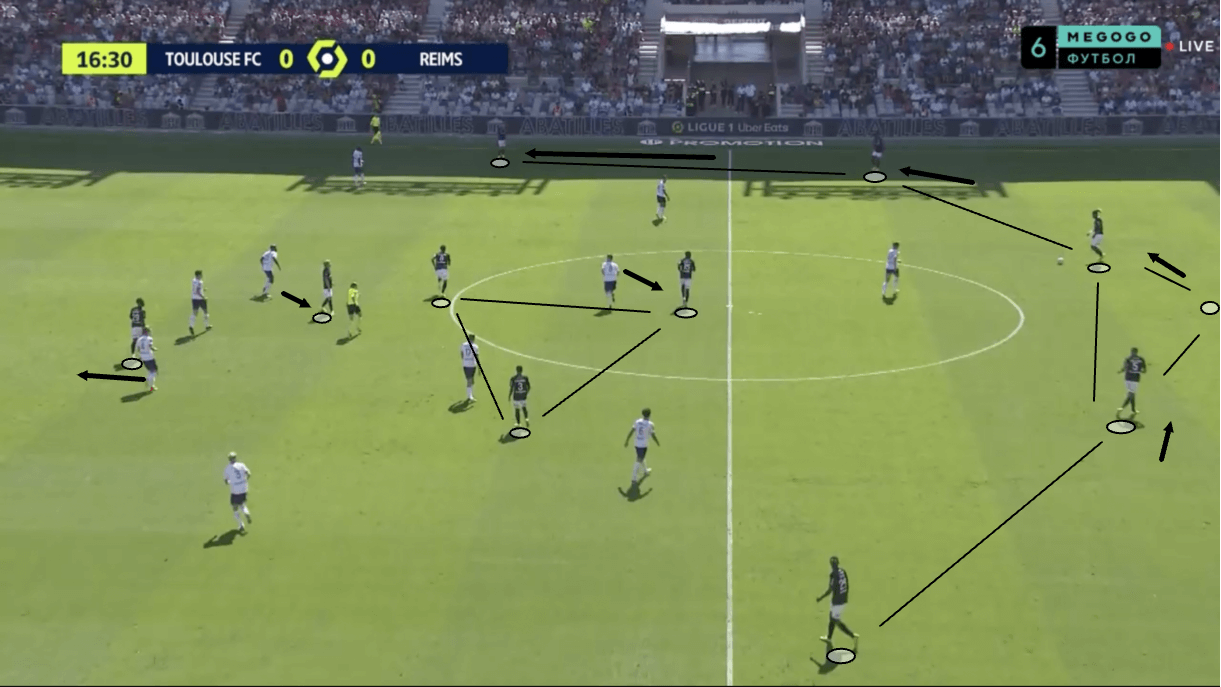

Les Rouges et Blancs don’t have a forward who provides a significant aerial presence but they do operate with a structure designed to pounce on the second balls resulting from these aerial duels after the goal-kicks, as we see in figure 1. Two midfielders position themselves close to the aerial duel, ready to jump on the second ball, should the ball bounce in their area.

Organisation, spatial awareness, pace, power and work rate are all key components for the players to possess in such situations in order to emerge from the ensuing duel with the ball in their feet. Reims’ midfielders must possess these traits and attributes in this team given the importance of winning second balls to their team’s offensive game.

We’ve already concluded that García’s Reims side is not a heavily possession-based team and this is evident from observing their build-up play. As García has said, the players at hand ultimately dictate his team’s style of play, and Reims’ defenders/goalkeeper are not comfortable enough with the ball at their feet to play a high-risk game out of the back.

Even with the limited amount of time they’ve spent with the ball at their feet passing around in deeper areas, they’ve been caught out and put under serious pressure via a high transition following an error in possession; this is clearly not an area in which this team excels.

However, they do still attempt to draw some pressure from the opposition at times in order to create extra space further upfield for the goalkeeper or centre-backs to find an advanced teammate in space.

This kind of play will typically not see Reims’ deep-lying players perform a plethora of passes but given that they’re often targeted with aggressive pressure due to the knowledge of their unsuitability for ball-playing tactics, they do, at times, try to get away with playing some safe passes around the back, drawing the press and thus creating space further upfield before then launching the ball forward, targeting a player in space.

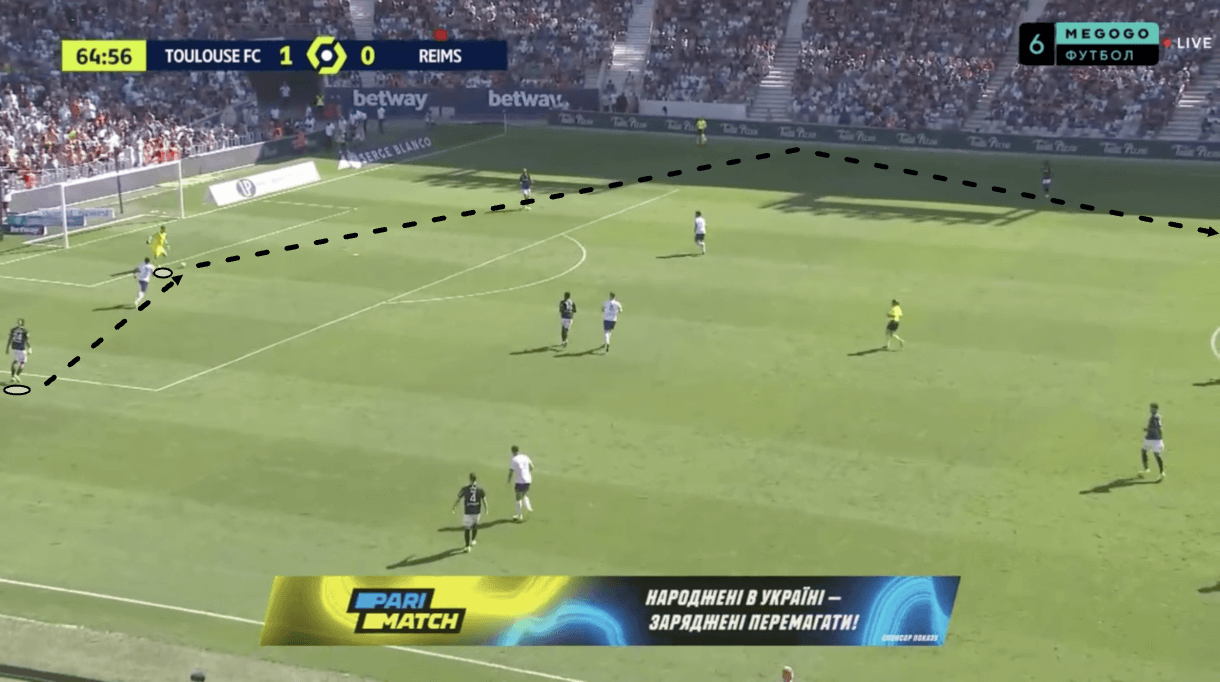

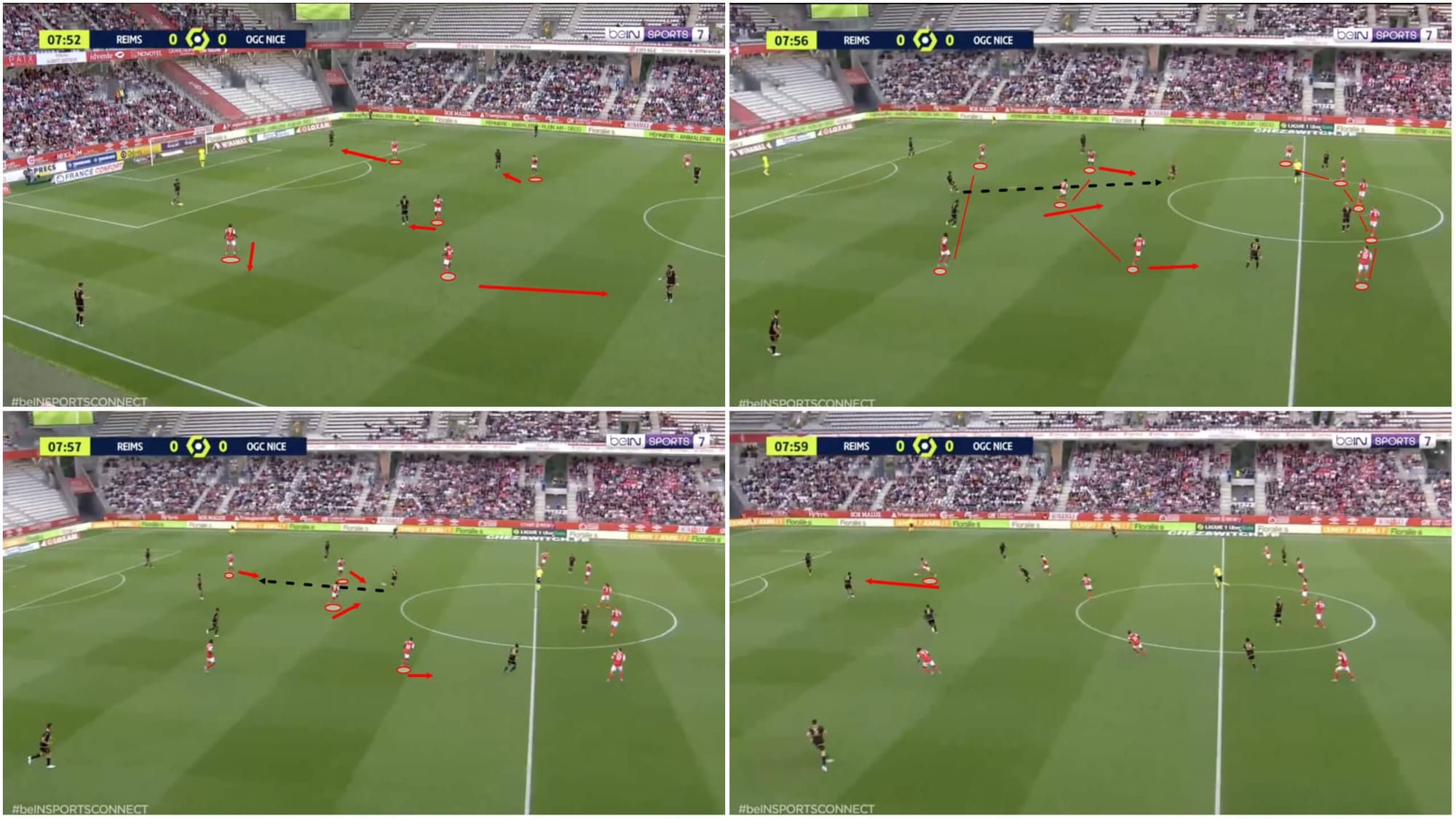

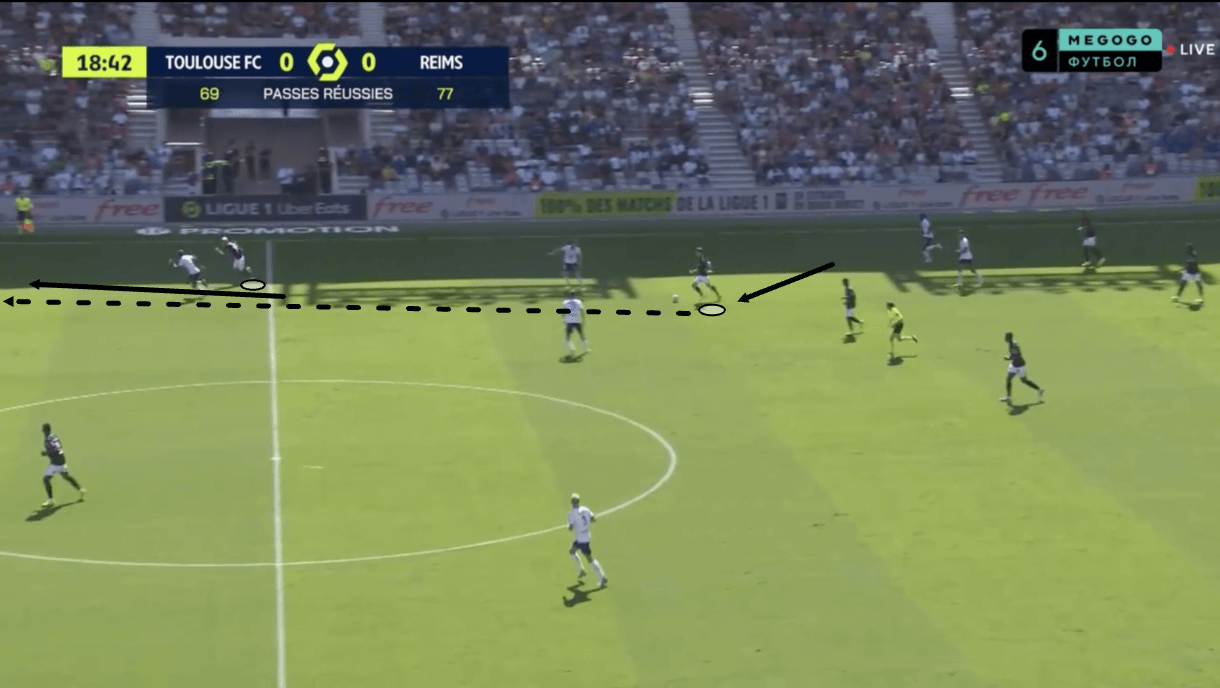

We can see an example of this in figures 2-4, with figure 2 above showing Reims drawing the opposition’s aggressive press to create space behind the pressing players.

We see that the ‘keeper’s long ball was well placed to meet his dropping teammate in the number ‘10’ position’s movement behind the opposition’s midfield line in figure 3.

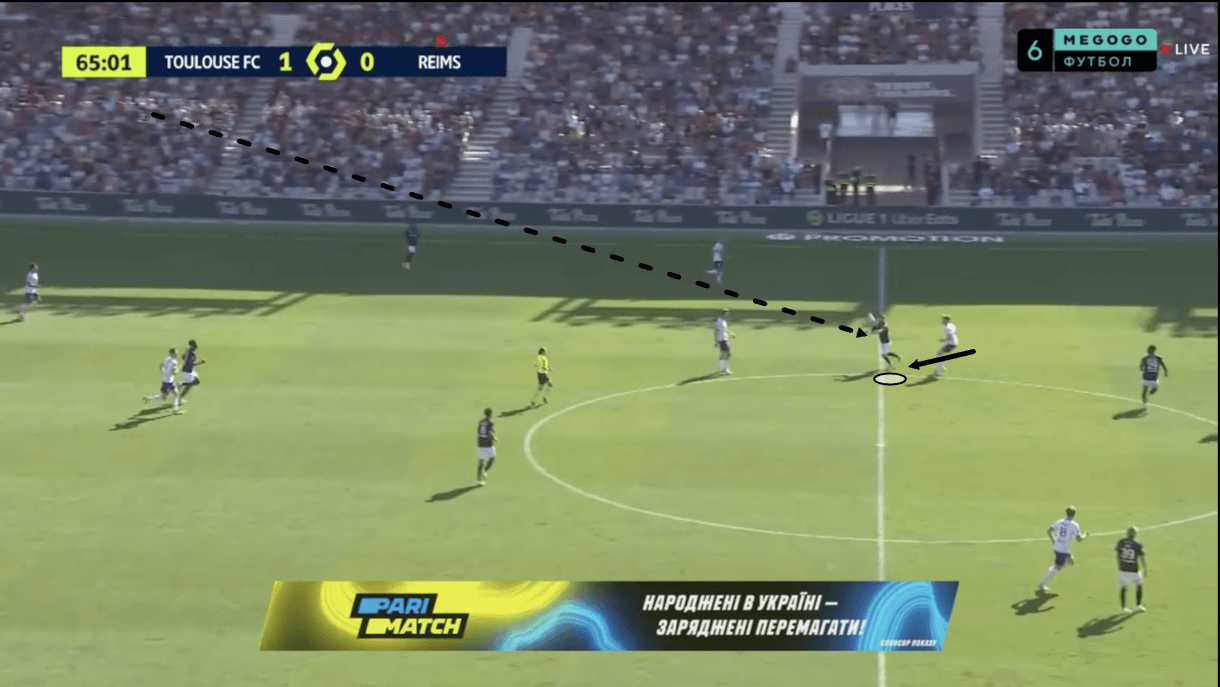

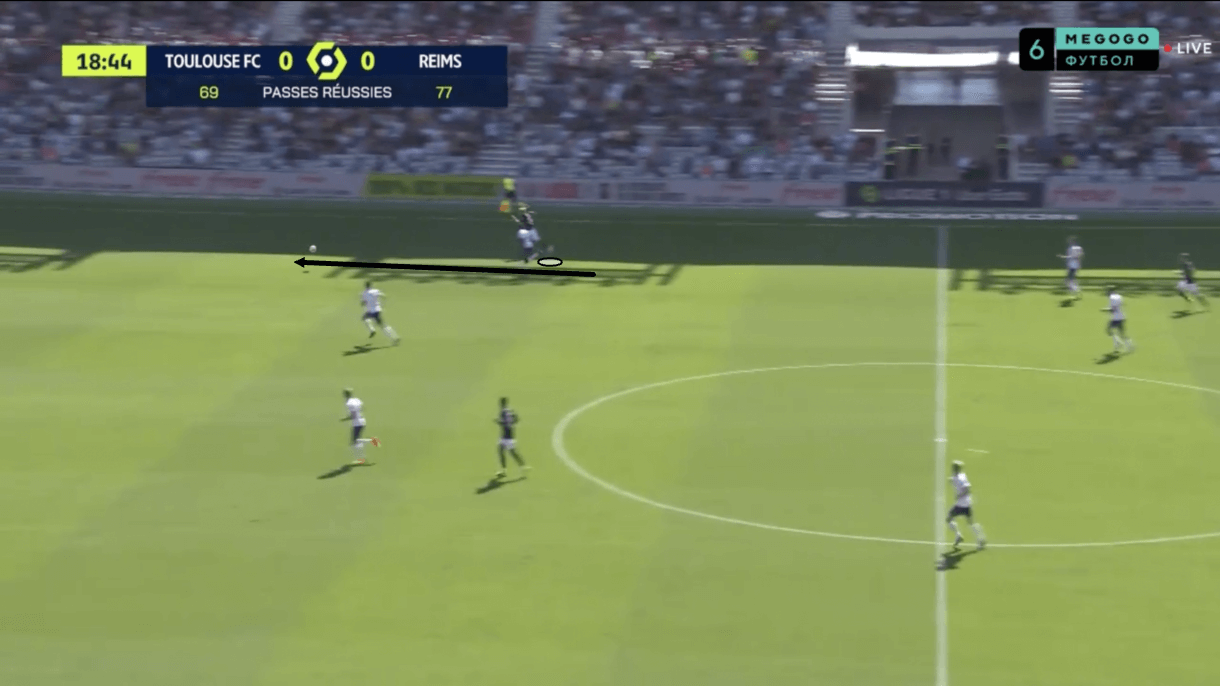

Then, moving on to figure 4, we see that the attacker did well to control the ball, turn and lay it off to Junya Ito in the right-sided second-striker role he’s primarily performed this term, while his strike partner on the left tries to provide him with a passing option by targeting the space behind the opposition’s backline with their probing run.

This is a typical example of how we see Reims’ attacks form and their attacking trio set up in terms of positions and roles this term; expect to see García’s side trying to get the ball forward quickly, find a way to create some link-up between the front three and aim to create a quick overload versus the opposition’s unprepared backline following the extremely quick vertical progression.

Reims don’t focus too much on accurate long balls out from the back right into a teammate’s feet, even if the previous passage of play showed an example of the ‘keeper performing a pinpoint ball to find the ‘10’ in between the lines. If the accurate ball is on, they may well go for it but the main focus is often on just drawing the opposition press upfield and getting the ball sent forward to an area in which they have players ready to put the opposition under pressure.

This, of course, still requires passing accuracy but less so than when aiming to find a teammate. Figure 5 shows an example of one passage of play in which Reims pulled off this long ball from the back, launching the ball to an opposition player surrounded by Reims shirts pressing aggressively.

While the first tackler fails to dispossess the opposition man, he does well enough to force the opposition ball carrier into a 50/50 duel with another Les Rouges et Blancs man who had followed the initial press closely. This next player was successful in dispossessing the opposition ball carrier and ultimately ended up driving forward with the ball, leading to a big overload over the opposition’s defence for García’s side.

Again, this is exactly how García’s team wants to attack — getting the ball forward quickly, either finding a teammate in space, dispossessing an opposition player via aggressive pressure or winning the second ball resulting from the initial direct play and quickly forcing an overload versus the opposition’s unprepared backline.

Reims can surprise the opposition defence via attacks like this that hinge upon defensive organisation, spatial awareness and compactness, along with certain physical traits and a good defensive work rate.

Technical skill on the ball is important in any team and particularly comes to the fore for Reims when they get the ball to the front three and those players look to link up with one another. However, these aforementioned traits are more evident during the earlier stages of Reims’ vertical, direct attacking tactics — they rely heavily on their skills and tactics without the ball rather than with the ball.

Reims’ pressing

García’s side ended last season with the eighth-highest PPDA in Ligue 1 (13.49), while they’ve currently got the ninth-highest PPDA in France’s top flight for 2022/23 (12.08). Les Rouges et Blancs evidently aren’t the most aggressive team in France without the ball, just about falling on the more passive side of things in terms of PPDA for the last two campaigns.

Their focus when defending is not on winning the ball as closely as possible to the opposition’s goal or winning it back as quickly as possible through super aggressive pressing. Reims play with a very organised defensive structure that’s, yes, designed to win the ball back high and create counterattacking opportunities from dangerous positions for Les Rouges et Blancs, but that’s also designed to lure the opposition into certain positions before getting aggressive with their pressure in specific zones where García’s men have prepared to do so.

García’s side typically defend zonally, in a position-oriented manner. The strikers will orientate themselves in relation to the ball at times, while the midfielders/wing-backs may move towards players who enter space in their designated zones but the system is largely very disciplined and organised in a position-oriented zonal marking style.

Occasionally, the centre-backs may get drawn into high duels as well, but generally, they tend to avoid engaging high, remaining the most disciplined of all within this squad and typically only running out to engage if Reims are in serious trouble when defending a counterattack, which can happen if the opposition breaks beyond their rest defence structure, particularly the midfield line which is generally comprised of the two central midfielders and two wing-backs when defending transitions.

Reims set specific pressing traps to lure the opposition into an area in which they feel comfortable aggressively closing down the ball carrier. They tend to press from out to in from the front, aiming to force the opposition to play centrally.

After the ball is forced forward to the midfield line centrally, Reims’ press goes from quite passive to very aggressive as they look to close in on the central receiver like the walls closing in on our heroes in a film thanks to a dastardly trap laid out by the villain.

Following this, Reims’ pressing players will either look to engage the ball carrier in a defensive duel to dispossess them or, even better as it avoids the Reims players from even having to get their shorts dirty, their pressure will force the opposition player into an error which they can capitalise on. We see an example of the latter result, as well as the other steps in this process in figure 6.

Note that Reims don’t tend to apply a great deal of pressure to the opposition’s backline and are typically happy to give these players space and time to pick out a pass, but they will look to block off passes to the wings and press from out to in, in order to influence this player to pass through the centre, triggering Les Rouges et Blancs’ press to really start as figure 6 demonstrates.

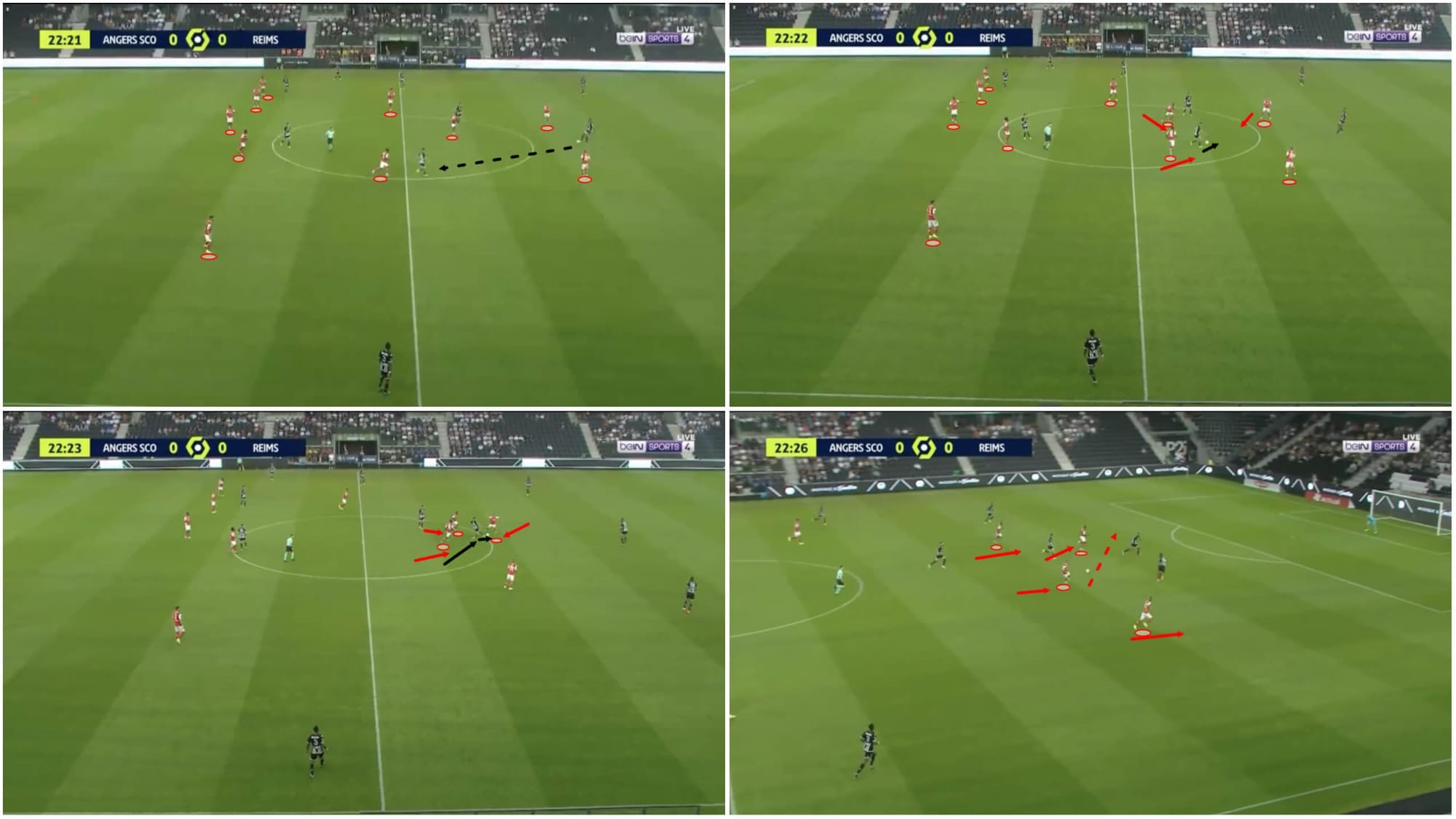

We see another example of Reims’ press working exactly as described above in figure 7. The big difference here is that Reims can be seen operating in a mid-block rather than the high-block they went with in figure 6.

García’s side like to play in the mid-block, drawing the opposition out a bit before forcing the central pass and creating the opportunity to transition. This allows more space to form behind the opposition’s backline for Reims’ attackers to target — and throughout his time at Stade Auguste-Delaune, García has had a player in his forward line in most games who loves to attack the space in behind, from Ekitiké last season to on-loan Arsenal man Folarin Balogun this term.

So, the organised pressing structure described earlier and central pressing traps seen in figures 6 and 7 are key elements of García’s defensive tactics in that they prevent the opposition from building out from the back comfortably but also the 49-year-old’s offensive tactics in that they can force high turnovers that then lead to great counterattacking opportunities for Les Rouges et Blancs from threatening positions.

Build-up and ball progression

So, we’ve already established that García’s side is not a heavily possession-based one and often tends to go long from goal-kicks with the aim of winning second balls in midfield before charging forward aggressively to try and put the opposition defence on the back foot quickly by creating an overload following the direct play.

However, Reims also sometimes start their attacks with some quick, short passing plays from the goal-kick to draw the opposition’s press high upfield and create space behind those pressing players that they can then target with their long ball.

This can be risky for Reims as they don’t really have many players in deep positions who are comfortable under pressure on the ball, but it’s a tactic that can pay off for them as we observed in the first section of our analysis.

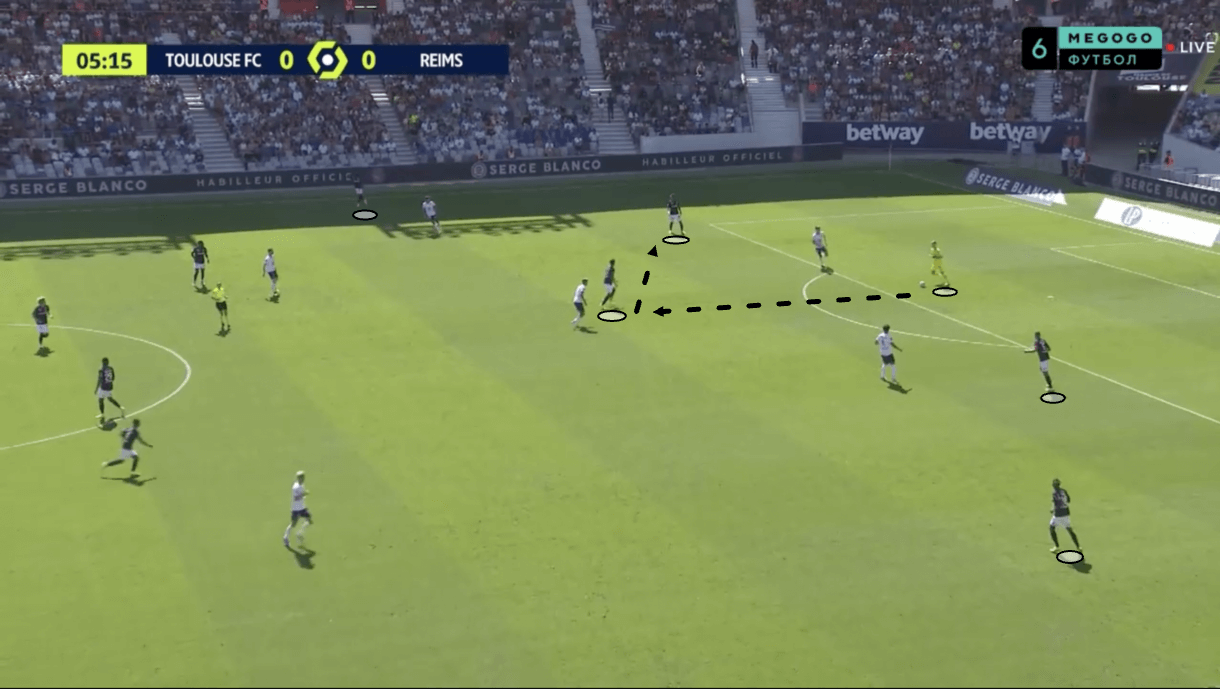

When playing short passes around the back in this fashion, it’s common to see Reims shape up as we see them in figure 8. Their back five shifts to the right, with the right wing-back pushing high up the wing, right centre-back converting into a right-back, and the rest of the backline shifting over until they’ve got the left wing-back in a typical left-back position as figure 8 demonstrates.

Meanwhile, one of their midfielders will drop deeper to provide a central passing option just behind the opposition’s first line of pressure. With this player coming under pressure from behind himself in figure 8, he intelligently uses himself to just receive the ball and attract pressure towards himself before laying the ball off to the right centre-back, who could then look to get it forward.

This is a typical structure to see Reims using when aiming to draw the opposition high upfield in the build-up phase but, again, Les Rouges et Blancs are not perfect in this phase and can still be vulnerable to aggressive pressure.

Reims typically retain this structure when moving further upfield into the ball progression phase, as we see in figure 9. The newly-formed back-four remains intact while one midfielder remains deepest, just behind the opposition’s first line of pressure.

Their midfield trio will typically not sit alongside each other on the same horizontal line to make themselves more difficult to mark and help create better passing angles for each other and their other teammates, while it’s common to see Reims’ forward duo stagger their positioning too, with Ito typically dropping deeper this term and his strike partner — in this case, Balogun — remaining higher, threatening the space behind the opposition’s backline.

Again, this movement in opposite directions poses a significant threat to the opposition defenders as it makes the players much more difficult to mark and gives their teammates greater passing options.

Wing play

For the final section of this tactical analysis piece, we’re going to shine a light on Reims’ wing play. Particularly in transition, it’s common to see Reims targeting the opposition’s wings. This may be a result of the fact that their opponents often leave the wings open when they attack and send their wing-backs/full-backs forward, creating space for Reims to target on the counter after regaining possession.

However, Reims make a clear, deliberate effort to target this space with great regularity through movement from their wing-backs and in-to-out runs from their forwards, all of whom are typically very comfortable operating in the wide areas.

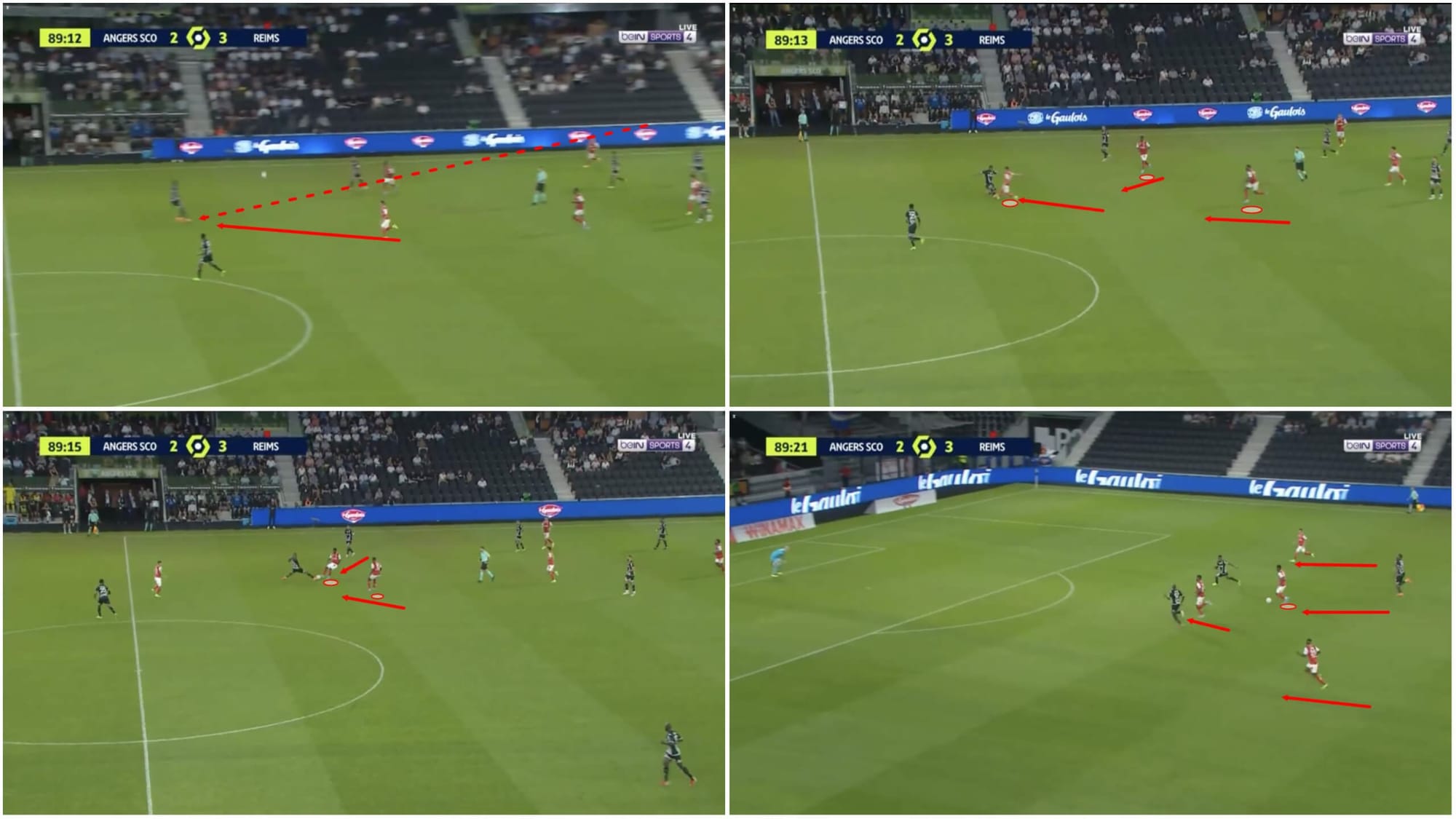

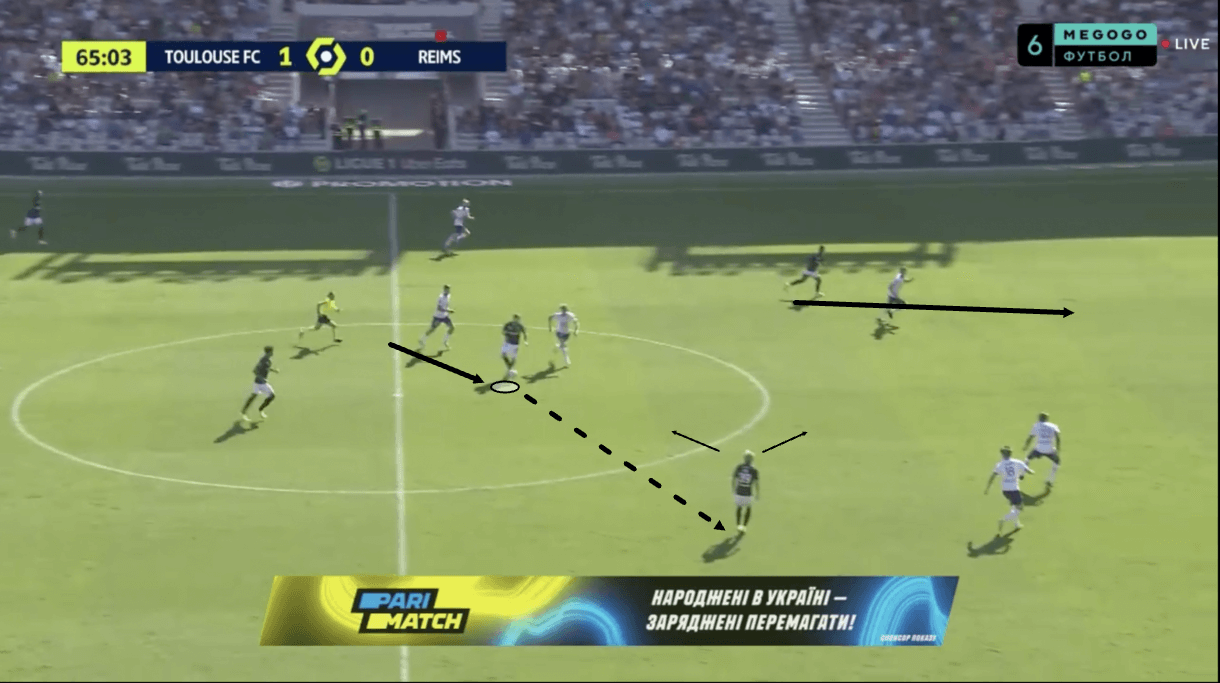

Take figures 10-11, for example. Just before figure 10, Reims regained possession just inside their own half. After the ball carrier here gets into some space where he can get his head up and assess his forward passing options, he sees the in-to-out run from Ito targeting the space that the opposition have allowed to open up on the wing for Les Rouges et Blancs to target.

As the play moves on into figure 11, we see that the ball was drilled through for Ito to chase down the wing and carry it into the final third for his side.

Reims’ intent to exploit this space on the wings in transition and their desire for their forwards to perform in-to-out runs like this with regularity is likely one key reason why García usually utilises a forward duo comprised of players who are very comfortable on the wings — the intent is for them to ultimately spend plenty of time in those areas.

Driving forward in transition to attack space that’s been left vacant on the wings is another way in which Reims can overload the opposition’s backline after quickly moving from one end of the pitch to the other — a key goal of their offensive play, as we discussed earlier in this tactical analysis.

Conclusion

To conclude this tactical analysis of Óscar García at Reims, the Cruyff-inspired coach performed well with Ligue 1’s youngest side last season, finishing in a respectable position on the table and he’ll hope to guide Les Rouges et Blancs to similar success if not even better this term, even after the departure of Ekitiké to PSG.

García is a major believer in a clear pathway from academy to first team and evidently believes in tactical flexibility from his own standpoint while being open to moulding his tactics to suit the available players.

At Reims, his young side’s tactical approach sees them focusing on creating chances via quick, direct attacks and vertical possession, with a large portion of Les Rouges et Blancs’ goalscoring opportunities coming from moments of transition or direct passing plays that quickly overwhelm the opposition’s backline with unexpected urgency.

Only time will tell if García can develop another Ekitiké at Reims this season but it certainly appears as though the La Masia academy product has fostered an environment designed to nurture his club’s natural academy resources and is providing them with every opportunity to grow into something exciting in the Ligue 1 side.

Comments