Scoring goals is the most difficult part of the game, so the ability to consistently create high-quality opportunities is extraordinarily valuable.

That’s the topic of today’s tactical theory analysis.

We’re going to examine how possession-dominant teams create high-xG shots.

The first topic of this tactical analysis focuses on creating chances through a team’s defensive tactics before turning our attention to in-possession approaches.

We’ll look at how these teams use both the wings and the central spaces to create quality scoring opportunities.

This is the first in a series on high-xG shot creation.

Setting a season average of 0.14 xG per shot as the minimum standard, we’ve identified clubs that range in possession percentage yet still produce top-end average shot quality.

As we progress through this tactical theory series, we’ll identify patterns that produce the highest-quality opportunities on goal.

Defending Tactics As A Playmaker

The first topic we’ll address is the way these possession-dominant teams defend.

It’s not quite the in-possession angle one would expect, but the press is widely regarded as a playmaker for possession-dominant teams.

That’s both in their structured out-of-possession approach as well as the way they counterpress.

Defending serves to create chances.

There’s no better place to start than with a quality opportunity generated by the high press.

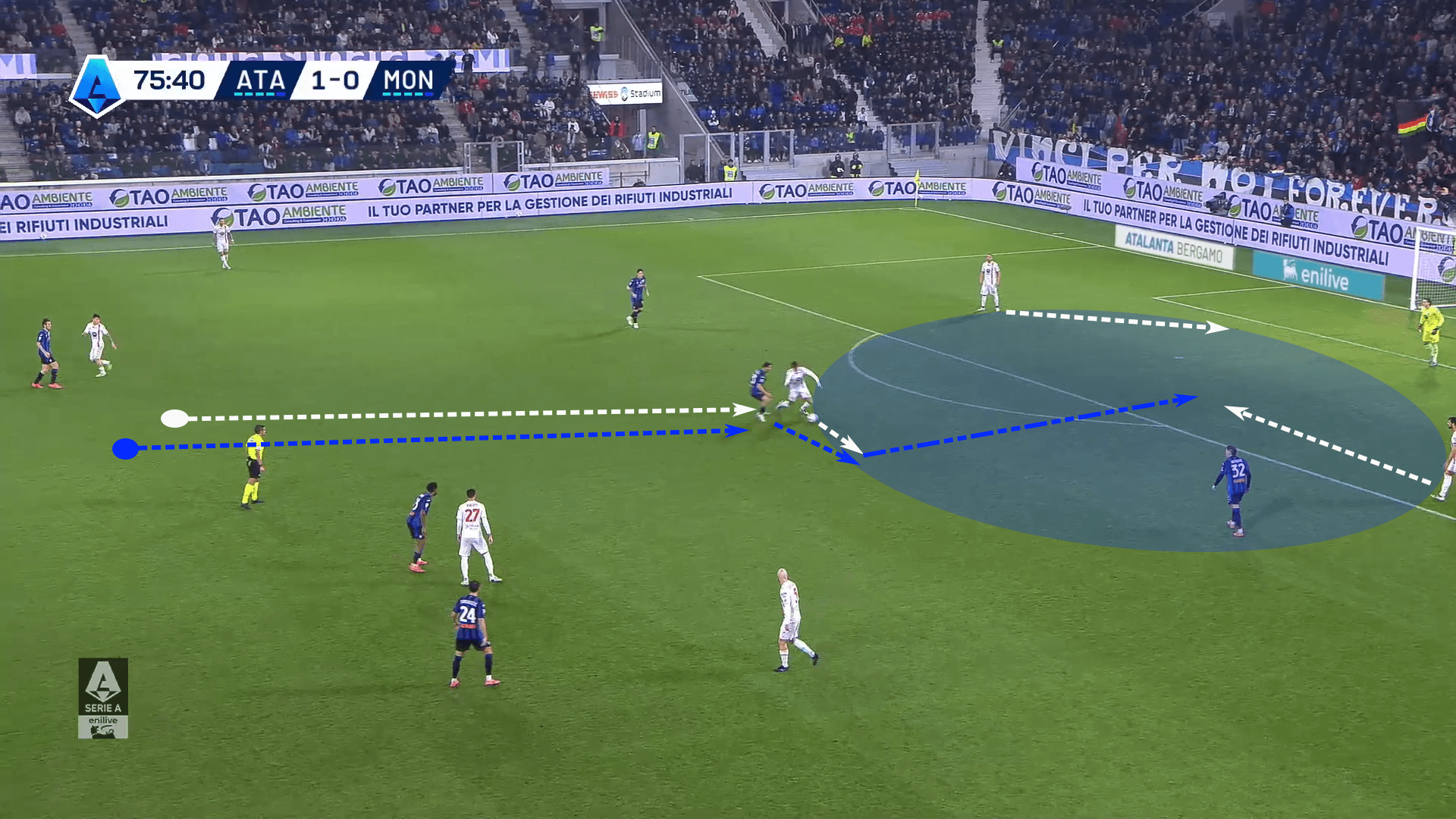

We’ll head to Serie A for the first example, looking at a well-executed press from Atalanta.

With Monza trying to play from the back through their goalkeeper, one of their midfielders dropped deep to receive the ball.

As he checked towards the ball, he had to lose his mark.

While he did initially have success, Atalanta’s man-marking midfield means the defender wasn’t far behind.

As the Monza midfielder took the bait and faced forward on the half turn, he was immediately met with an opponent in his face.

He tried to dribble free but was tackled on the play, leading to a shot from near the penalty spot with little pressure from the recovering centre-backs.

In the Atalanta example, the high press leads to a recovery of the first pass forward.

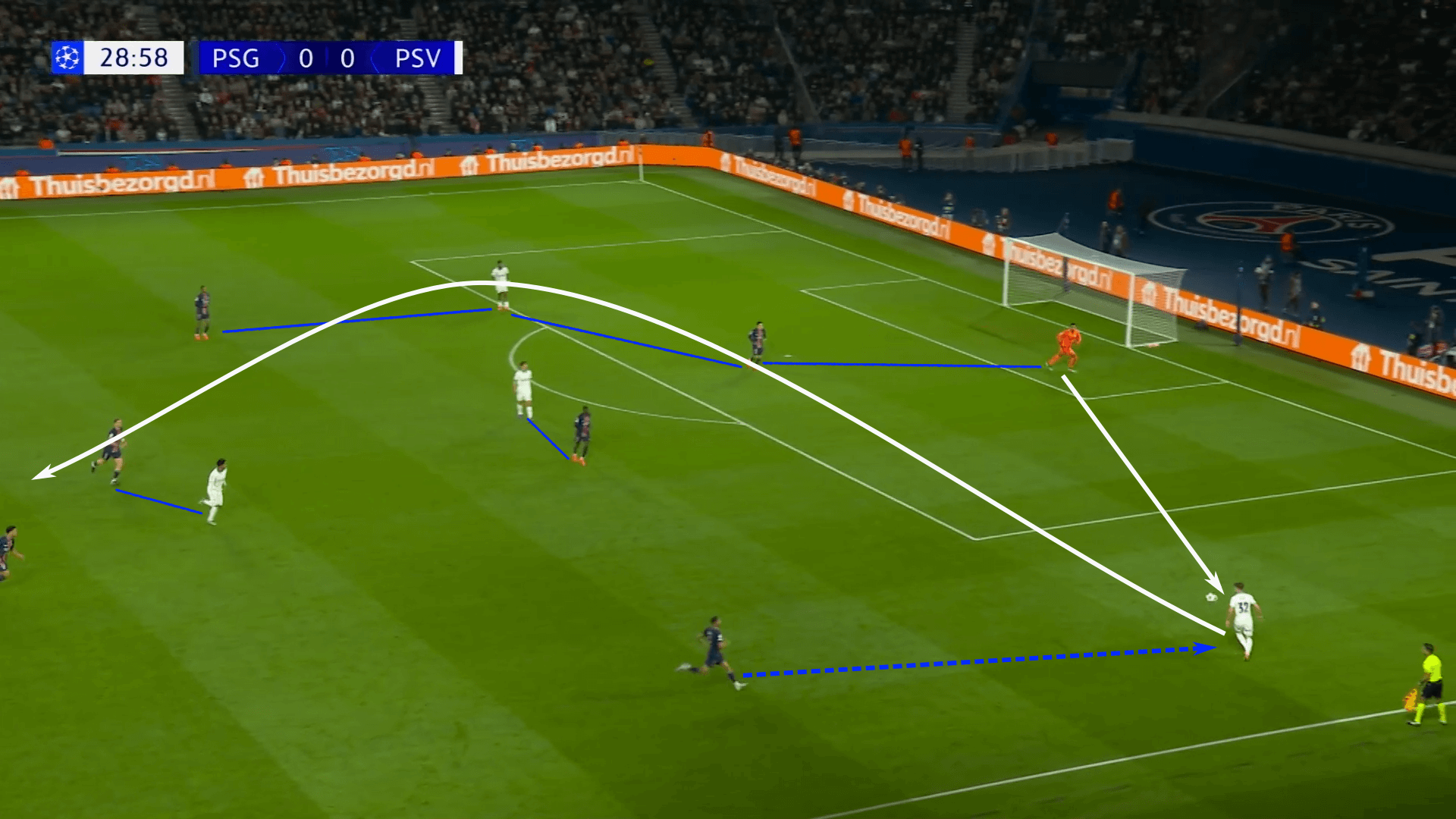

PSG’s UEFA Champions League match against PSV Eindhoven showed that it doesn’t necessarily have to be the first pass that’s won.

As PSV played into their left wing, PSG quickly applied pressure on the ball.

With no immediate options to play into and a bouncing ball in front of him, a clearance was the chosen option.

Unfortunately for PSV, it was a poor clearance right into the Paris Saint-Germain press.

PSG won the header and played Ousmane Dembélé into the box.

Much like the Atalanta attempt at goal, the defenders were poorly positioned to recover.

Dembélé has all sorts of time and space to get a quality shot off but hits one on the half volley and sends it over the goal.

With more composure from the Frenchman, a great scoring opportunity could have become a ‘gimme’.

Our final example comes from the Bundesliga.

VfB Stuttgart did well funneling their opponent into the wing and using a 4v3 advantage to increase pressure on the ball.

That pressure led to a hopeful play of the ball into the centre of the pitch.

Stuttgart recovered and immediately played the first pass forward.

A well-weighted through ball played them behind the backline, leading to a shot from about 12 m out that clanked off the post.

In matches where one side has a significant edge in possession percentage, the dominant team’s defence may produce the best chances.

While the team with less of the ball will typically refrain from maximum expansiveness in possession, they will typically be spread out enough to create counterattacking opportunities for the possession-dominant team.

If the press is well constructed, either setting traps or funnelling play to create recovery areas in more central spaces, high-xG shots are available.

Wing Play To Go Around The Press

Let’s move to the more typical means of creating goalscoring opportunities: the in-possession tactics.

One thing we see in matches where one team enjoys significantly more of the ball is that the centre of the pitch is often highly congested.

Playing around the press through the wings is a critical part of the puzzle.

Depending on the opponent’s out-of-possession tactics, the attacking tempo may accelerate in the middle or final thirds.

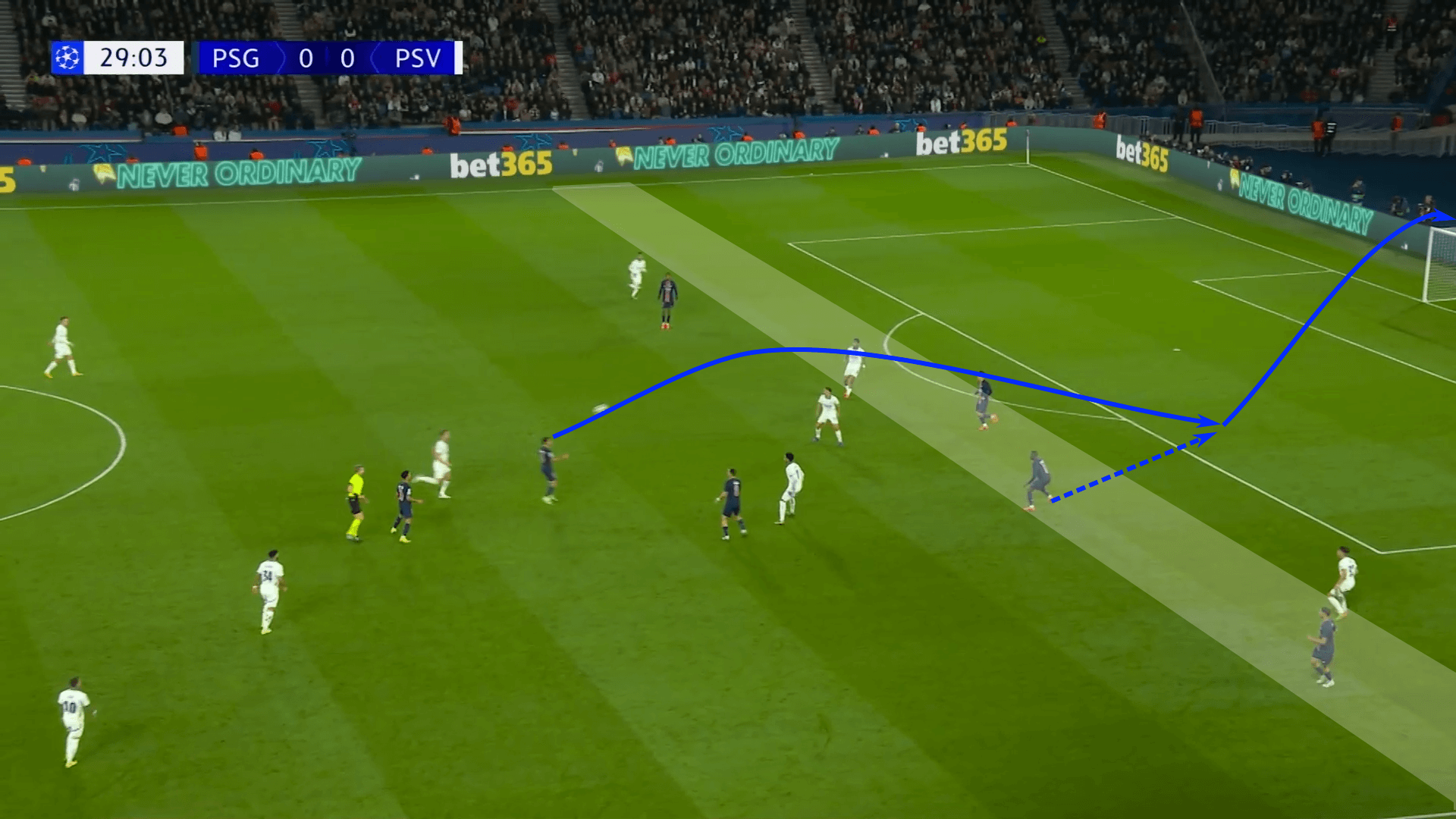

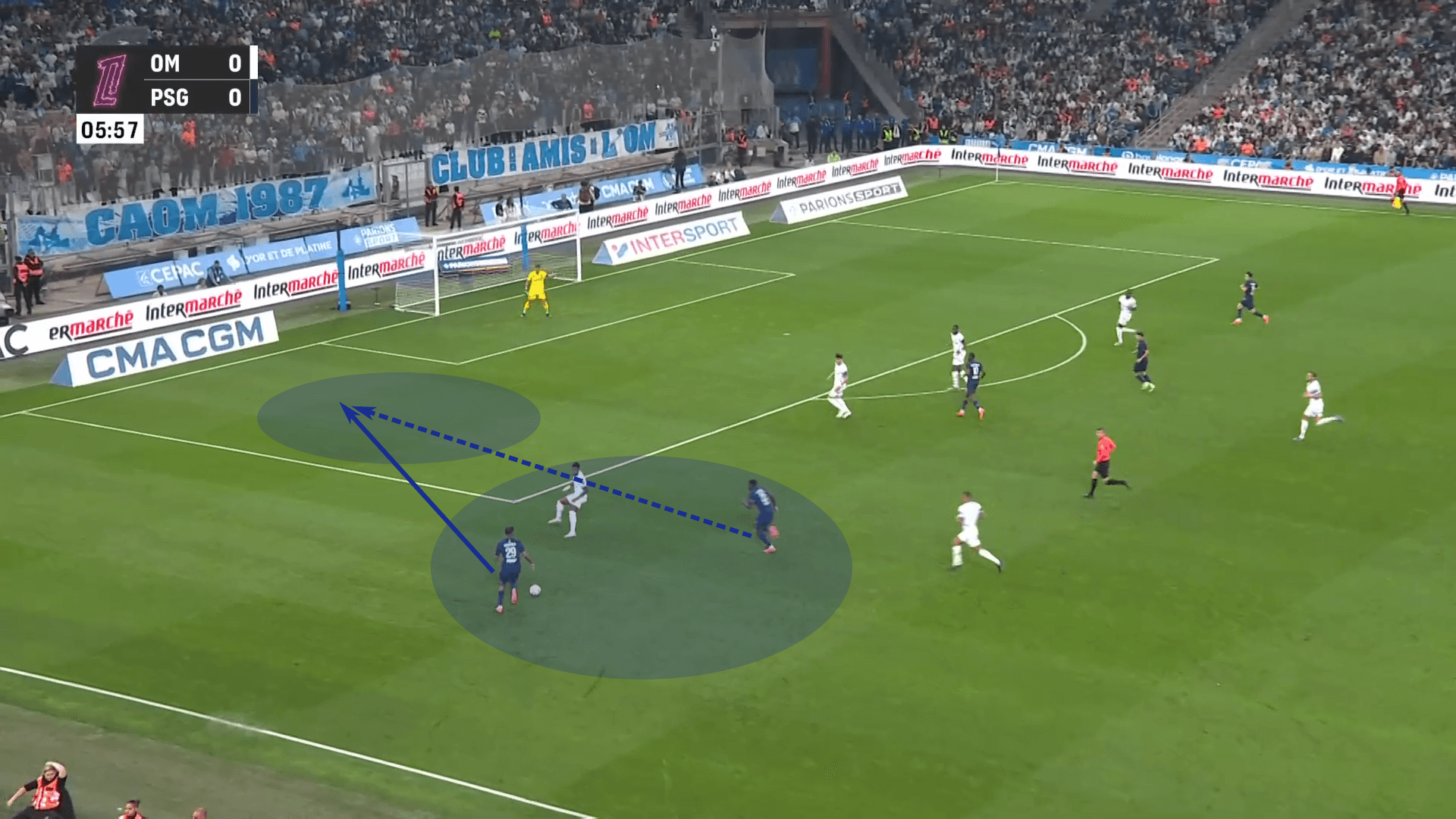

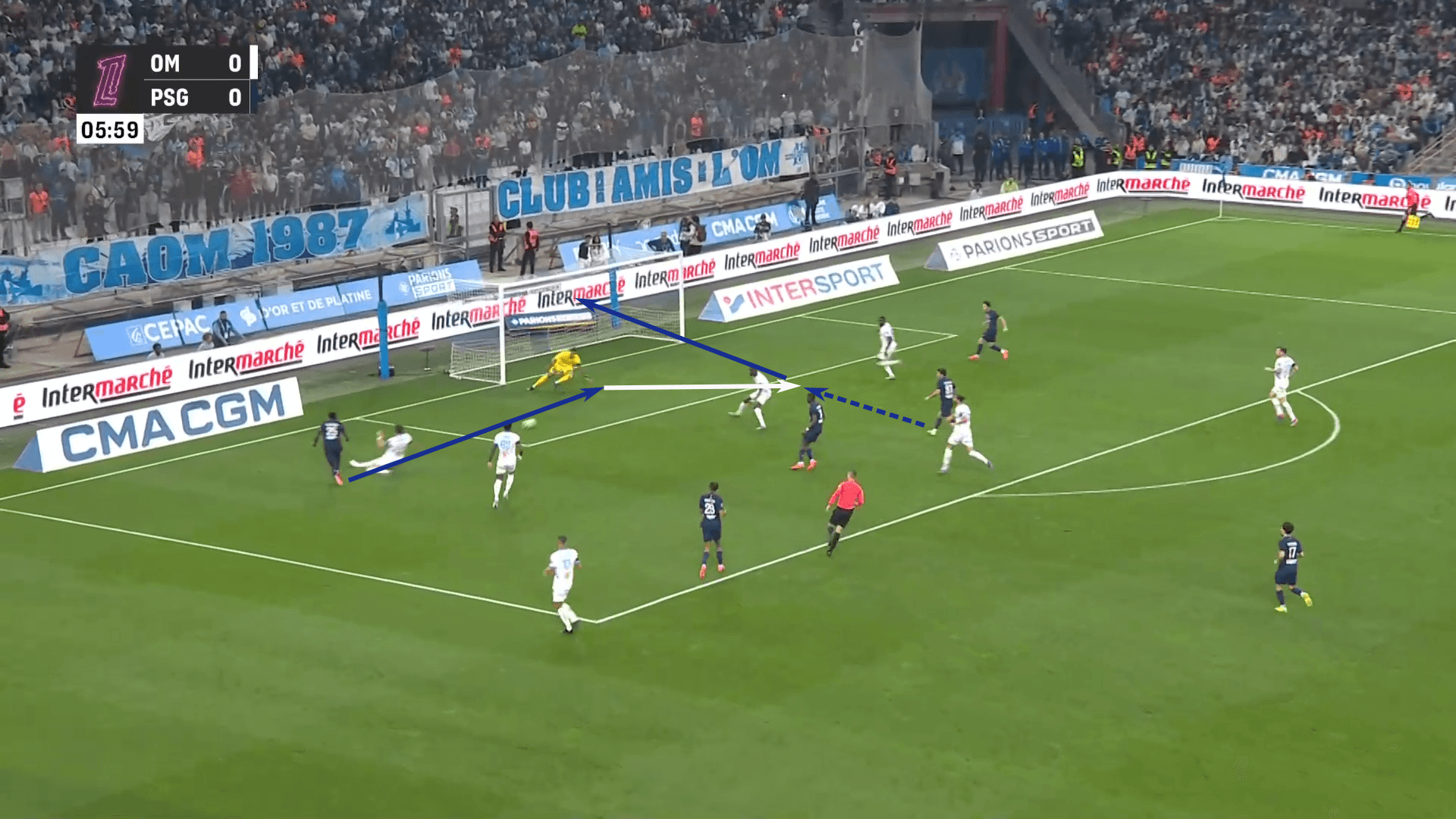

PSG offers a great example of attacking acceleration through the wings, with the Portuguese left-back Nuno Mendes getting forward in the attack.

He starts the attack near midfield and races forward to create a 2v1 in the final third.

A simple give-and-go puts him behind the backline and into the Marseille box.

His cross is intended for the far post runner, but the goalkeeper manages to get a hand on the ball.

With PSG well positioned for a rebound, anything but a hold from the goalkeeper could prove fatal.

That’s exactly what happens.

He pushes the ball into the heart of the box, onto the foot of João Neves for the close-range finish.

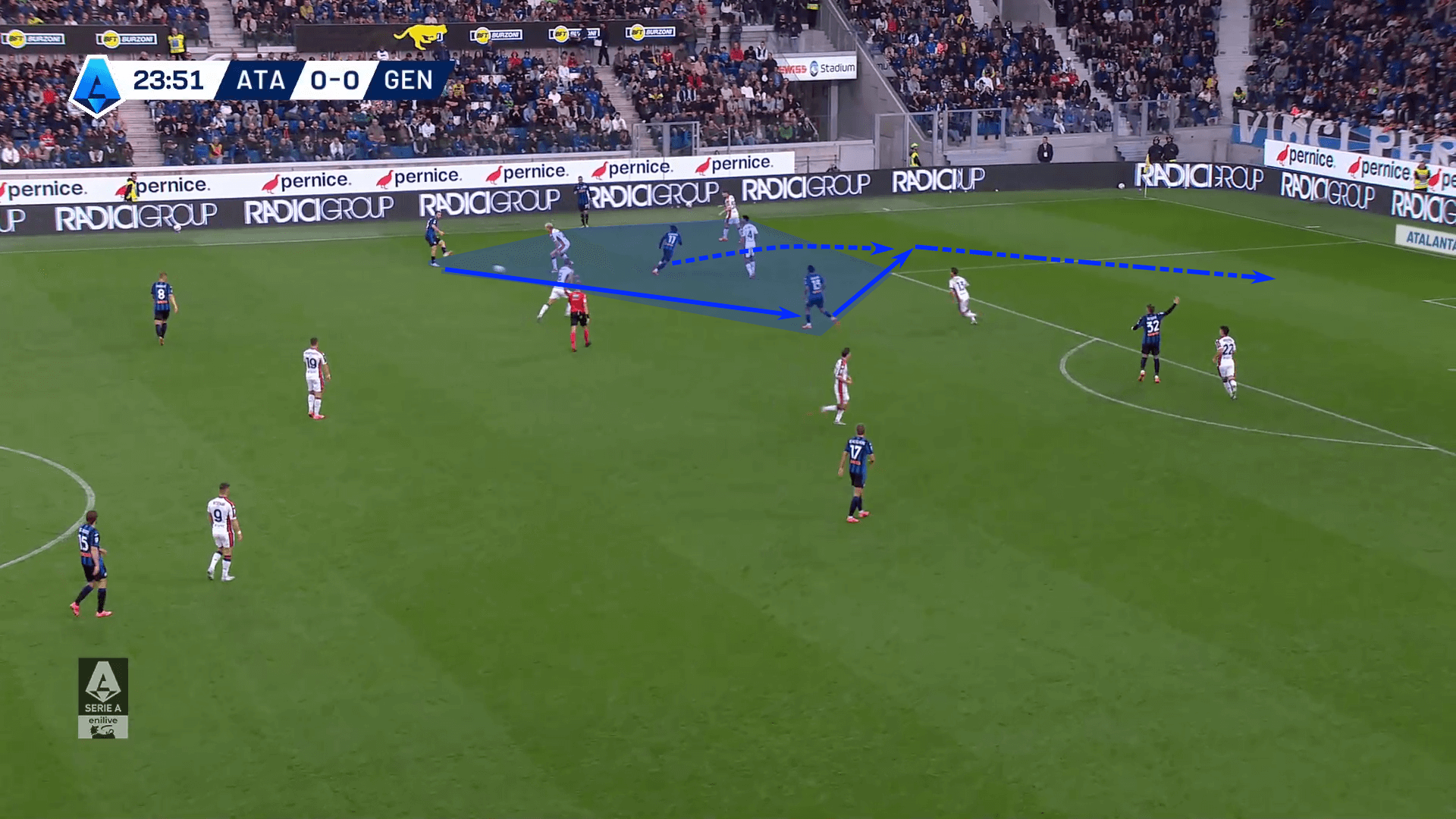

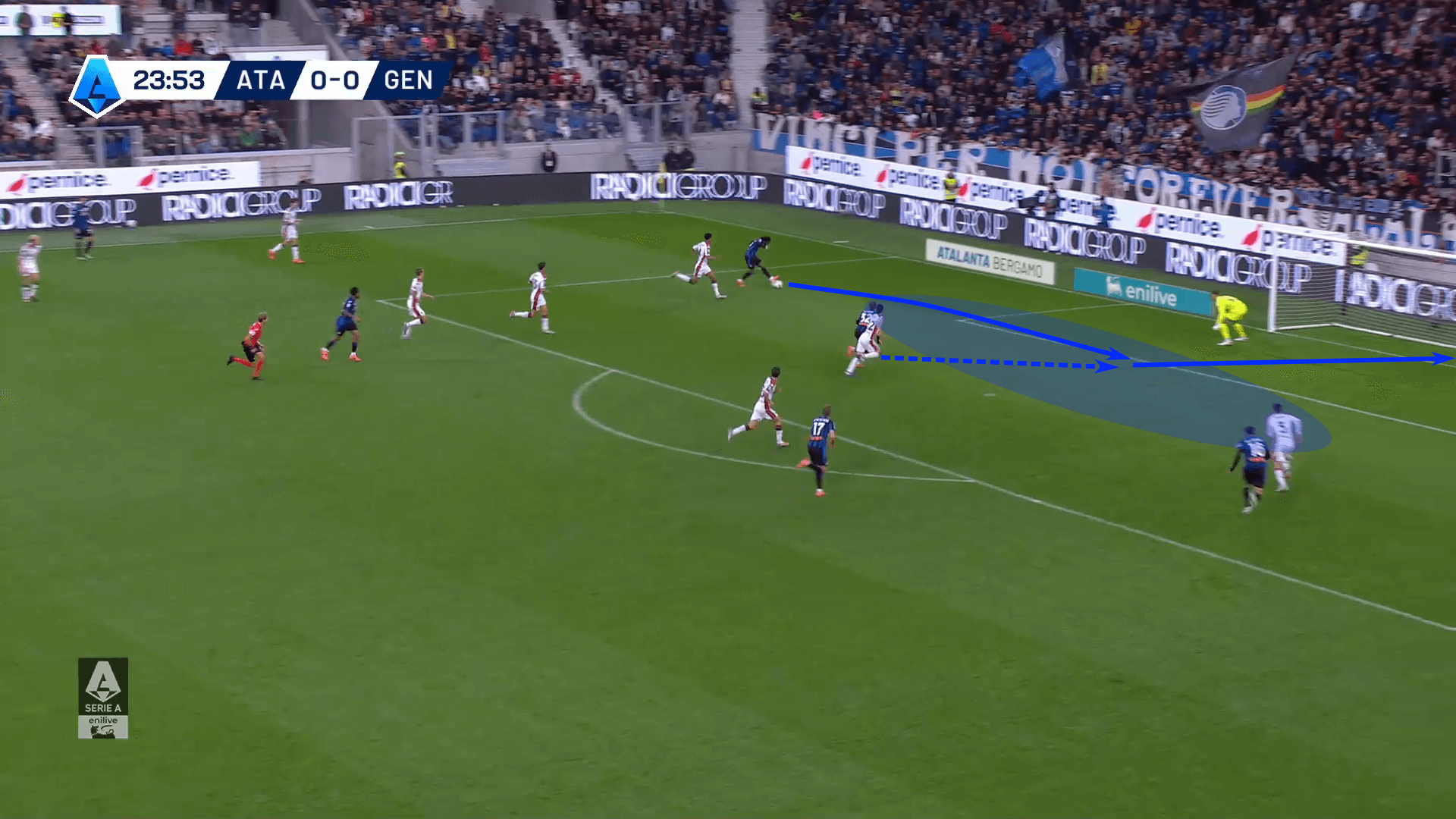

Returning to Bergamo, Atalanta has created a wide overload in their left-wing against Genoa’s low block.

Éderson’s late movement into the left half-space offers an option to play forward and draws a centre-back away from the centre of the pitch.

As the ball is played to the Brazilian, Ademola Lookman makes a run behind the backline and is played into space.

He drives into the box and hits a low, driven pass to Mateo Retegui for the first goal in a 5-1 route.

Atalanta’s movement and understanding within that high and wide overload created the opportunity to get behind the backline and drive into the box.

With so many players out wide, central, or behind the ball, La Dea found themselves 1v1 in the Box with their leading goalscorer ahead of his mark.

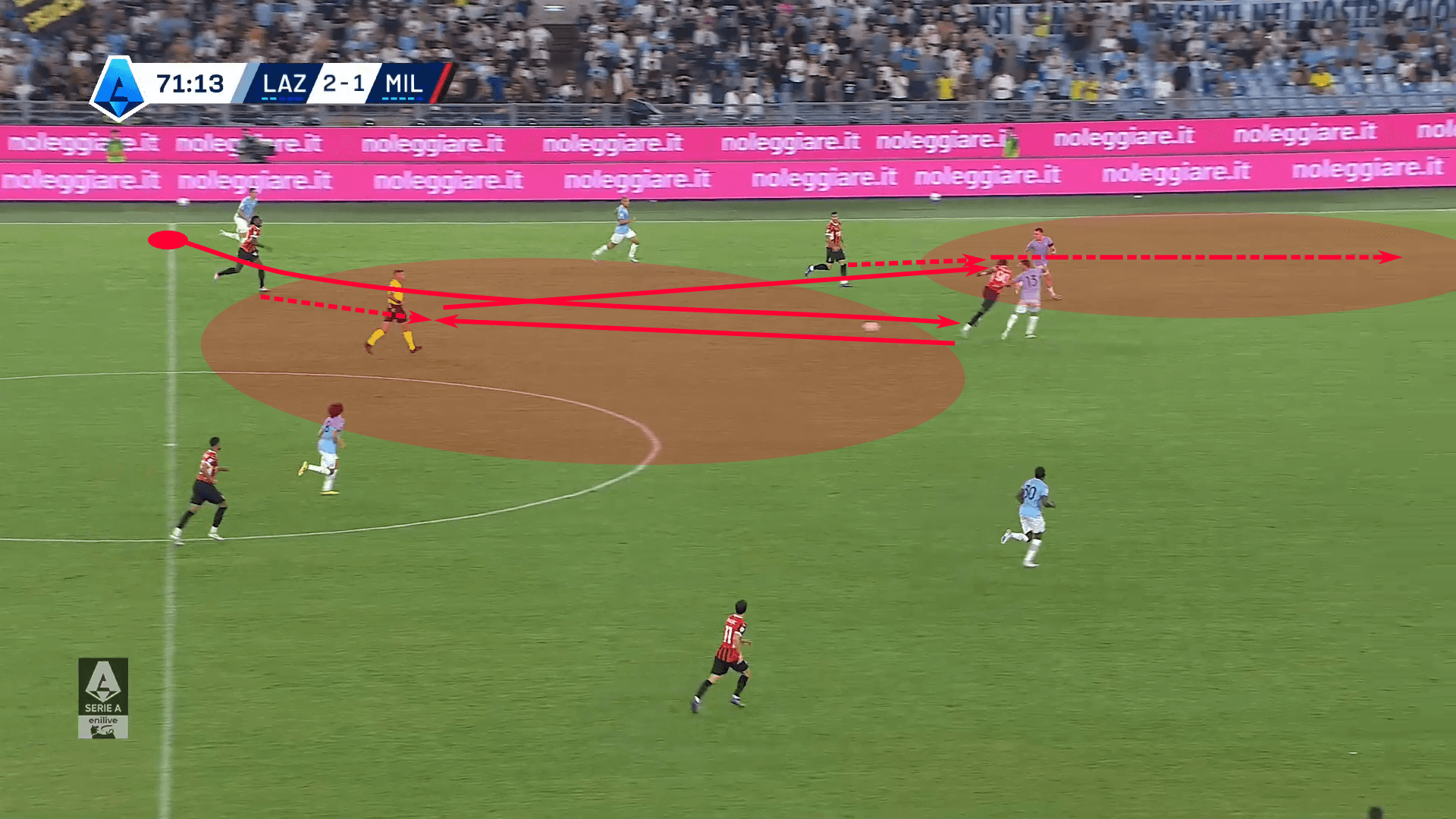

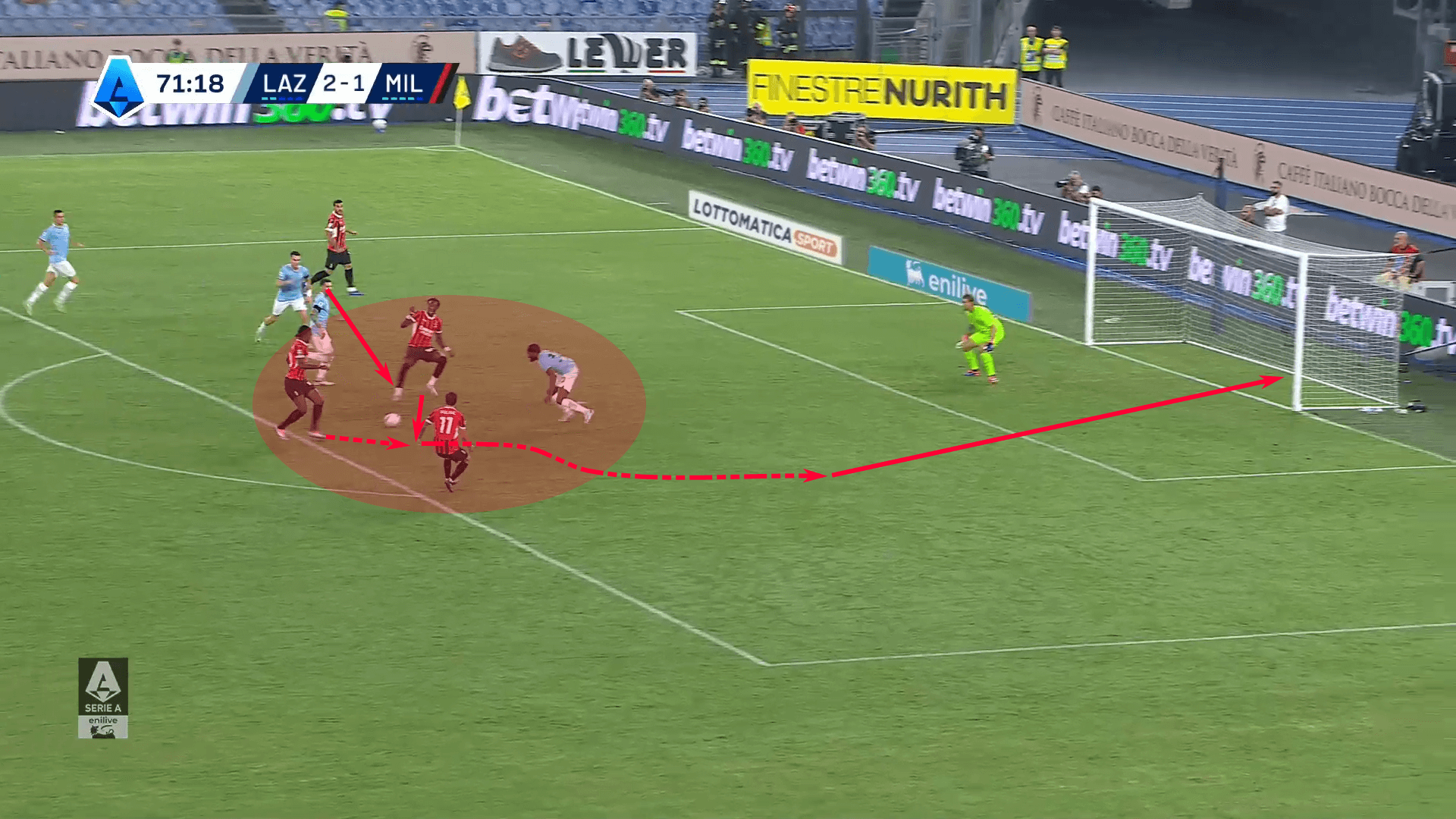

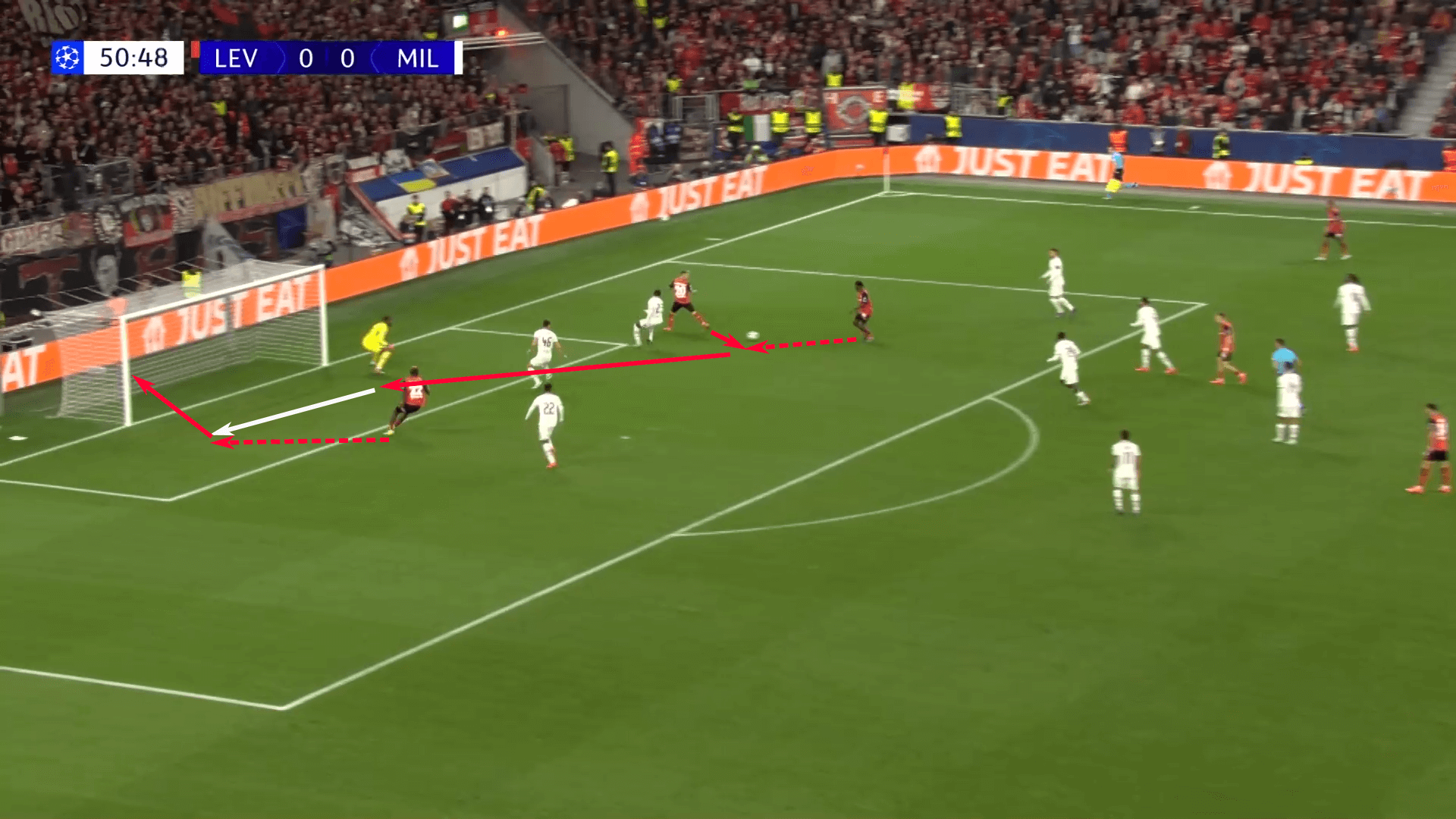

Staying in Italy, AC Milan offered a different path forward.

As Rafael Leão received the ball in the wing, he played directly into his #9, Tammy Abraham, who set the ball back into the path of his winger.

Leão immediately played forward into the path of Théo Hernandez.

The race to the goal was on.

Hernandez squared the ball into Abraham, who laid it off for Leão.

The Portuguese winger collected the ball at the top of the box, dribbled toward his right, and blasted the ball past the helpless goalkeeper from 8 m out.

That connection into the #9 initiated the up-back-through sequence.

Playing off the #9 allowed Abraham to set the ball into a forward-facing teammate underneath him in support.

That forward-facing orientation means the first attacker had a better opportunity to scan for options in front of him and pick out the best option to play forward.

Getting key players on the ball in a forward-facing orientation is a common theme within this article.

We see it once again in our final example from this section.

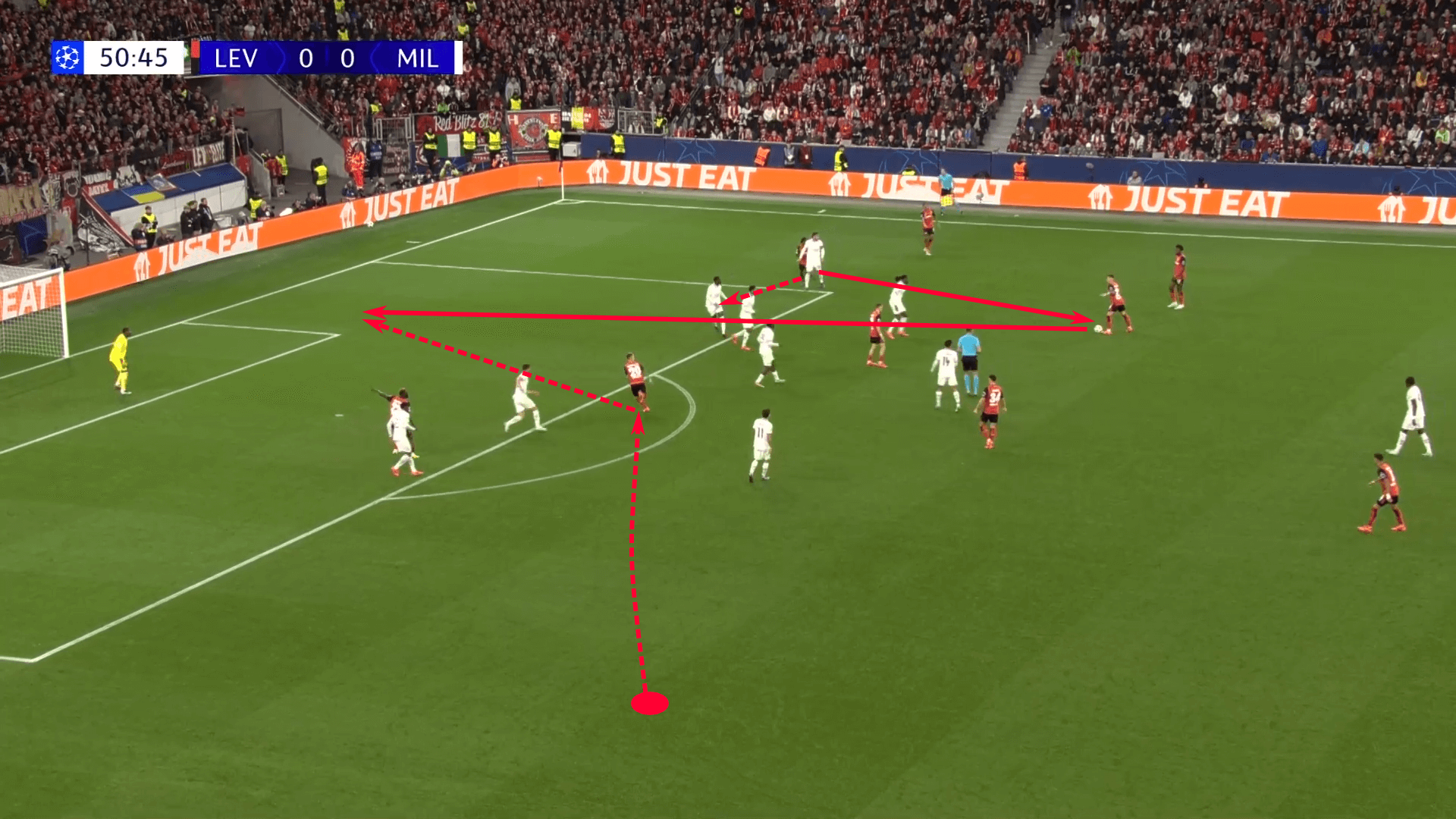

Xabi Alonso‘s Bayer Leverkusen gives us a scenario against a low block.

There is that element of wide overload that we saw with Atalanta, but the pitch is also more compact here.

Milan is now the defending team in this example, and they have nine players behind the ball.

Despite their numbers, Bayer Leverkusen does manage to get Aleix García on the ball and ready to play forward.

His line-breaking pass is received by Alex Grimaldo, the left-wing back who has run across the pitch to attack the right half-space.

That untracked run is played and supported underneath by Jeremie Frimpong.

A little flick to the Dutchman leads to a shot, save and a rebound goal for Victor Boniface.

The run behind the backline comes out of nowhere.

While AC Milan is trying to contain the Bayer Leverkusen wide overload, Grimaldo sees his opportunity long before that space opens up.

That combination of numbers high in the wing plus the collaboration of weakside runners to get behind the backline provided the winning goal.

When the opponent cuts off access to the centre of the pitch, wide overloads and getting behind the opposition in the half-spaces can unlock opportunities.

The willingness to get behind the line and the timing of the run with a forward-facing player getting on the ball are critical.

As deeper forward-facing players arrive in support and get on the ball, that’s one of the visual cues for the second and third attackers to initiate their runs.

Breaking Lines Centrally

Even if a team has set up to take away the centre of the pitch, there are those special, possession-dominant sides that can still find a way forward through the press.

That’s where we’ll turn our attention.

We’re no longer interested in finding examples that play around the press.

We want to figure out how to slice through the opposition lines.

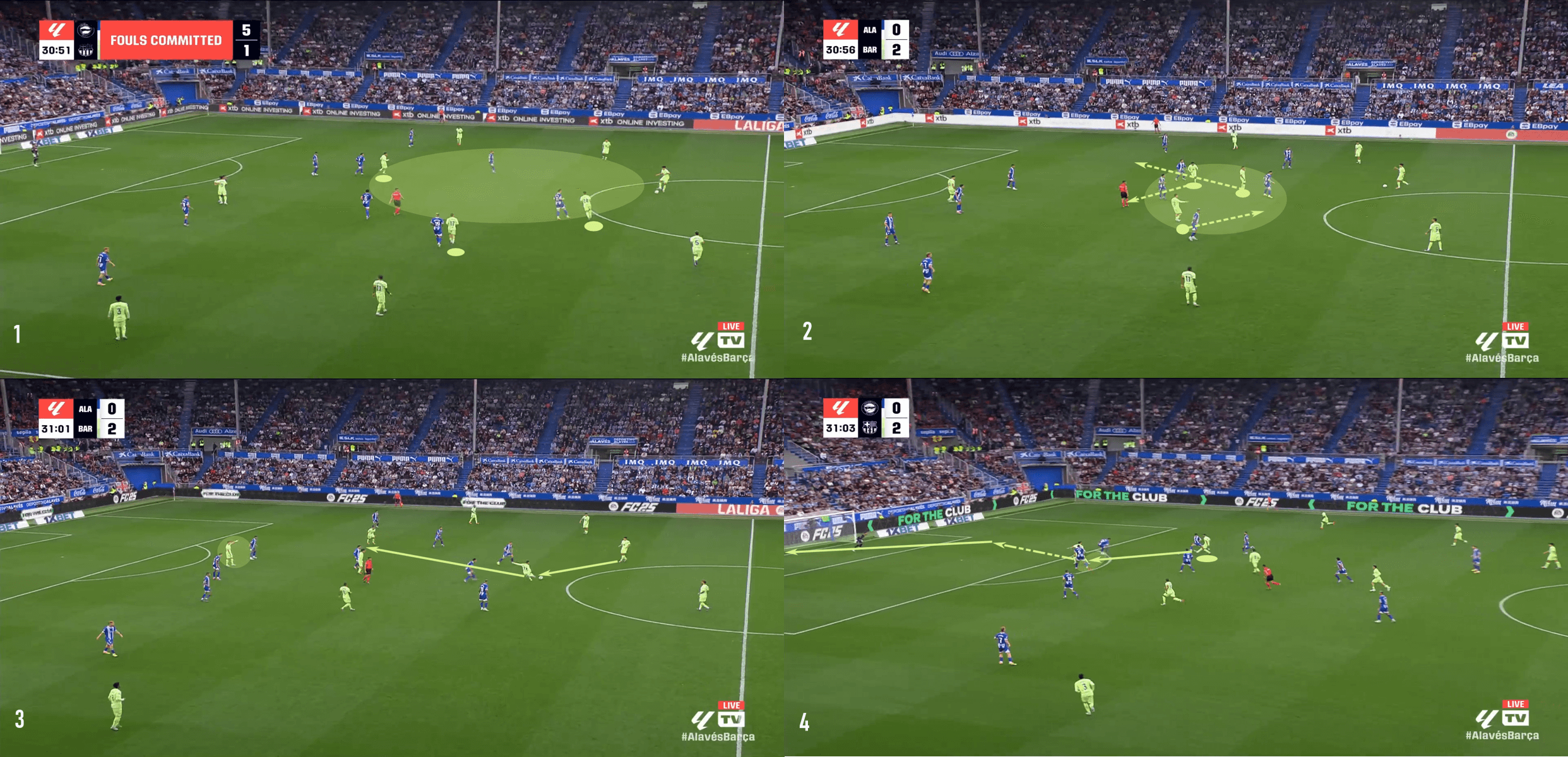

Perhaps there’s no better place to start than Hansi Flick’s Barcelona.

The sequence we’ve chosen to focus on is a very clever one.

In the first window, we see the large shaded area that’s virtually unoccupied and the three highlighted Barcelona players working their way into it.

In the second still frame, they’ve arrived in the shaded area and have momentarily stopped to draw the press as close to that now smaller shaded space as possible.

Deportivo Alavés takes the bait and fails to see the movements of those three players.

That leads to a line-breaking pass, followed by a ball that plays live Robert Lewandowski behind the backline and sets him in for a goal.

Barcelona’s midfield started with a more expensive shape and then moved to a compact area, with all three players virtually in the same space Alavés.

That clever movement allowed those three players to move freely.

Once they regained their spacing and had lanes to play forward, Alavés was at their mercy.

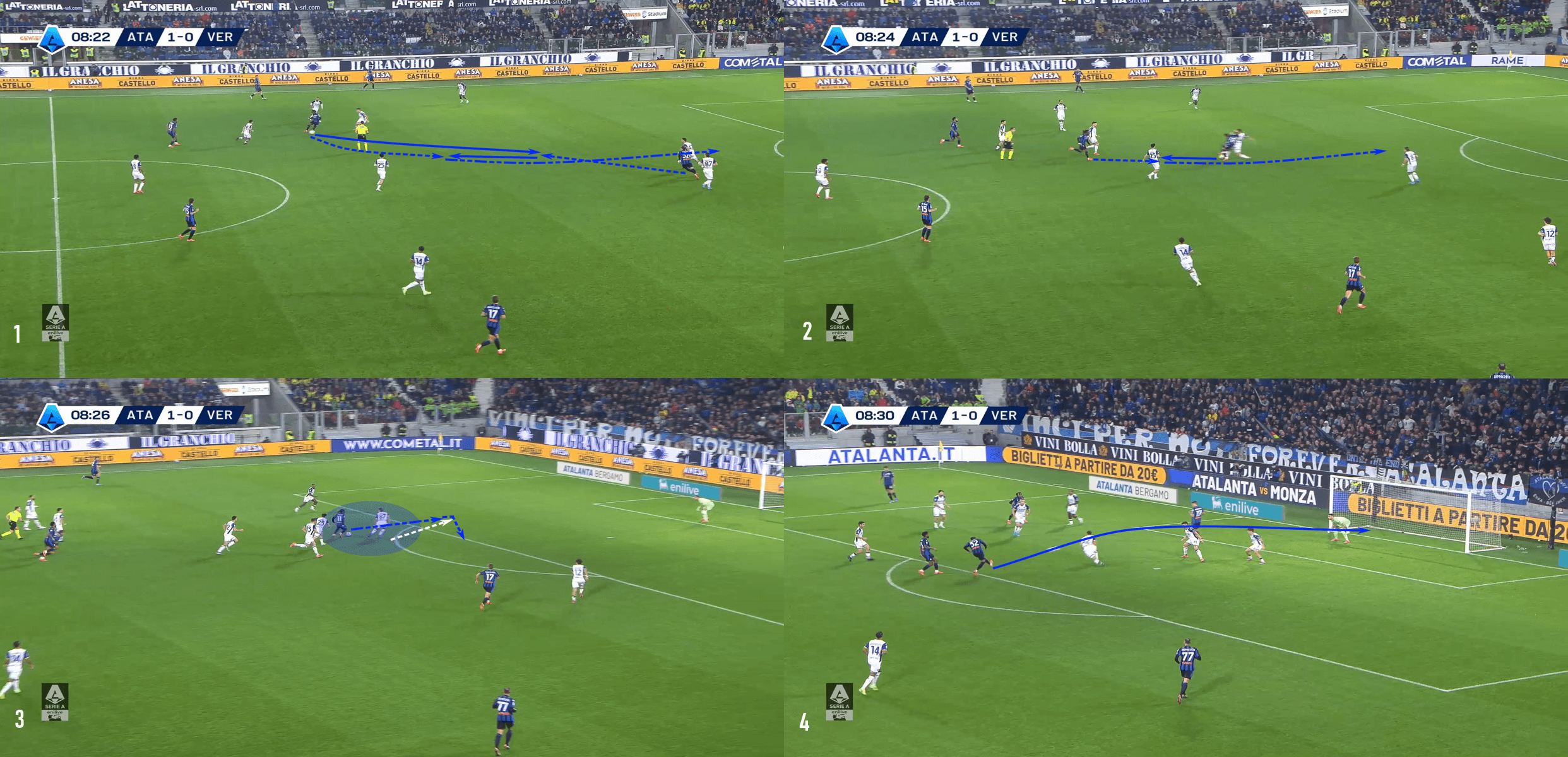

Whereas Barcelona played through their midfield, Atalanta gives another example of how you can play off the #9 to access the space between the lines.

In the 4-in-1 image below, Lookman is the danger man again.

As he cuts inside, he plays Retegui and moves underneath in support.

The ball is set into Lookman, who then takes a big touch to push the ball beyond the nearby defenders, leaving him 1v1 in the third frame.

His shot is blocked, but Retegui managed to get back on his feet, follow the play and provide a sumptuous first-touch finish past the goalkeeper at the near post.

That pass into the striker created the opportunity to get between the lines in the central channel.

As the ball travelled into the striker, untracked movements in support allowed Atalanta to get on the ball and drive forward with pace.

That shift in attacking the acceleration is a critical piece of these central attacks.

Even if the attacking team can get on the ball centrally, they are likely to be surrounded by opponents.

Any movements into the centre have to be met with well-hit passes and proper body orientation to maximise the efficiency of the attacking move.

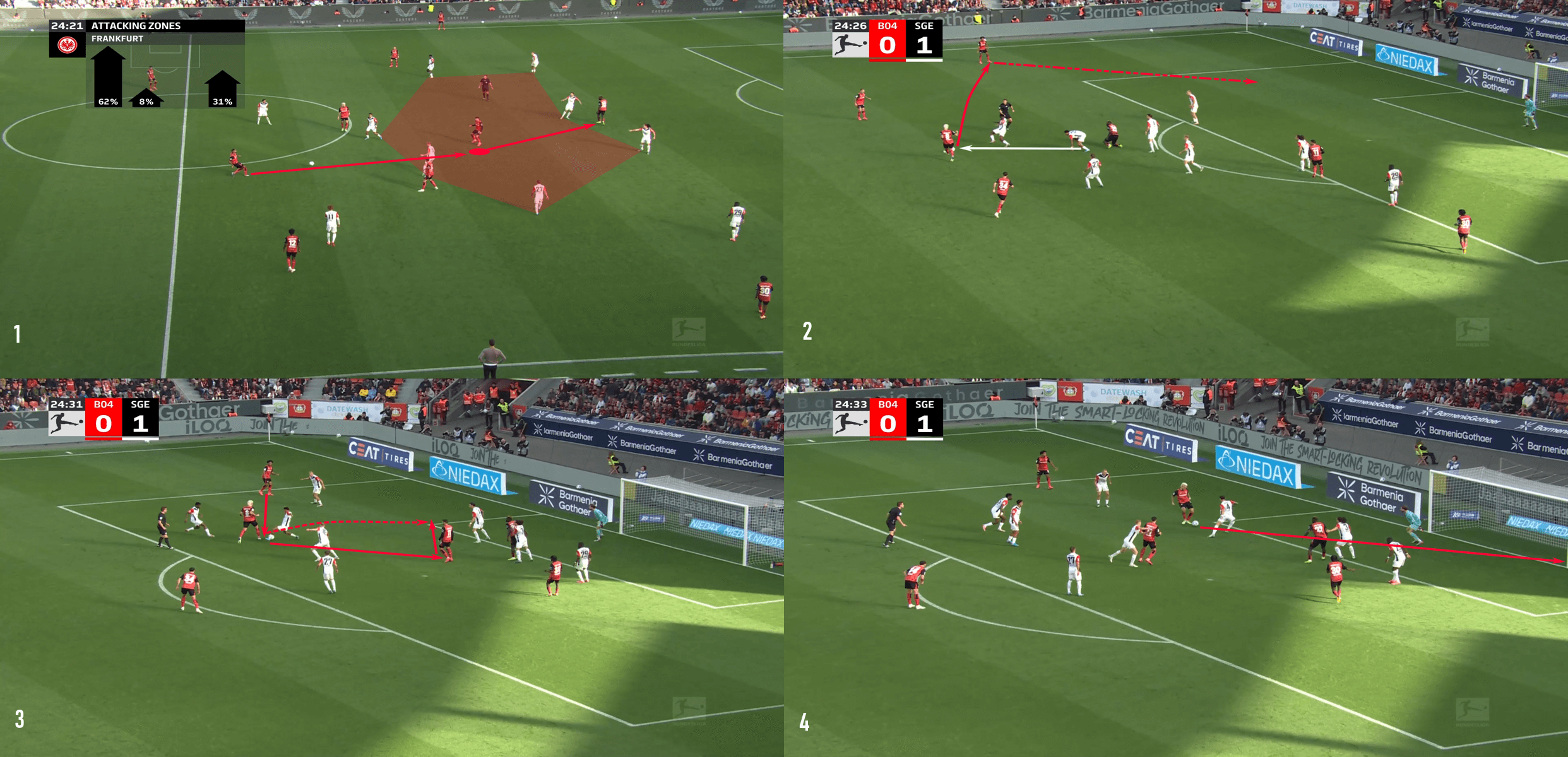

Bayer Leverkusen provides that example as they play forward to the man between the lines and immediately look to play off of the #9 and get into the box.

Their first attempt to get into the box through the central channel was snuffed out, and Frankfurt managed to get eight players behind the ball in the central channel.

That initiated the in-out-in pattern.

Robert Andrich played Amine Adli, who attacked the box with pace.

He found Andrich in the box with the negative pass.

The German used a deft give-and-go with Martin Terrier to get to the corner of the six-yard box before slotting the ball home for the equaliser.

The key takeaways from this sequence are to increase the attacking tempo when playing forward through the central channel and, if that first attack is unsuccessful, look for the free man in the wings, knowing that the opponent has collapsed near the ball.

Playing out to Aldi kept Frankfurt chasing the ball, leading to a second opportunity to attack through the centre.

Whether primarily targeting central or wide spaces, the last example, and the one from Stuttgart below, show that moving the ball into the wings can facilitate central attacks.

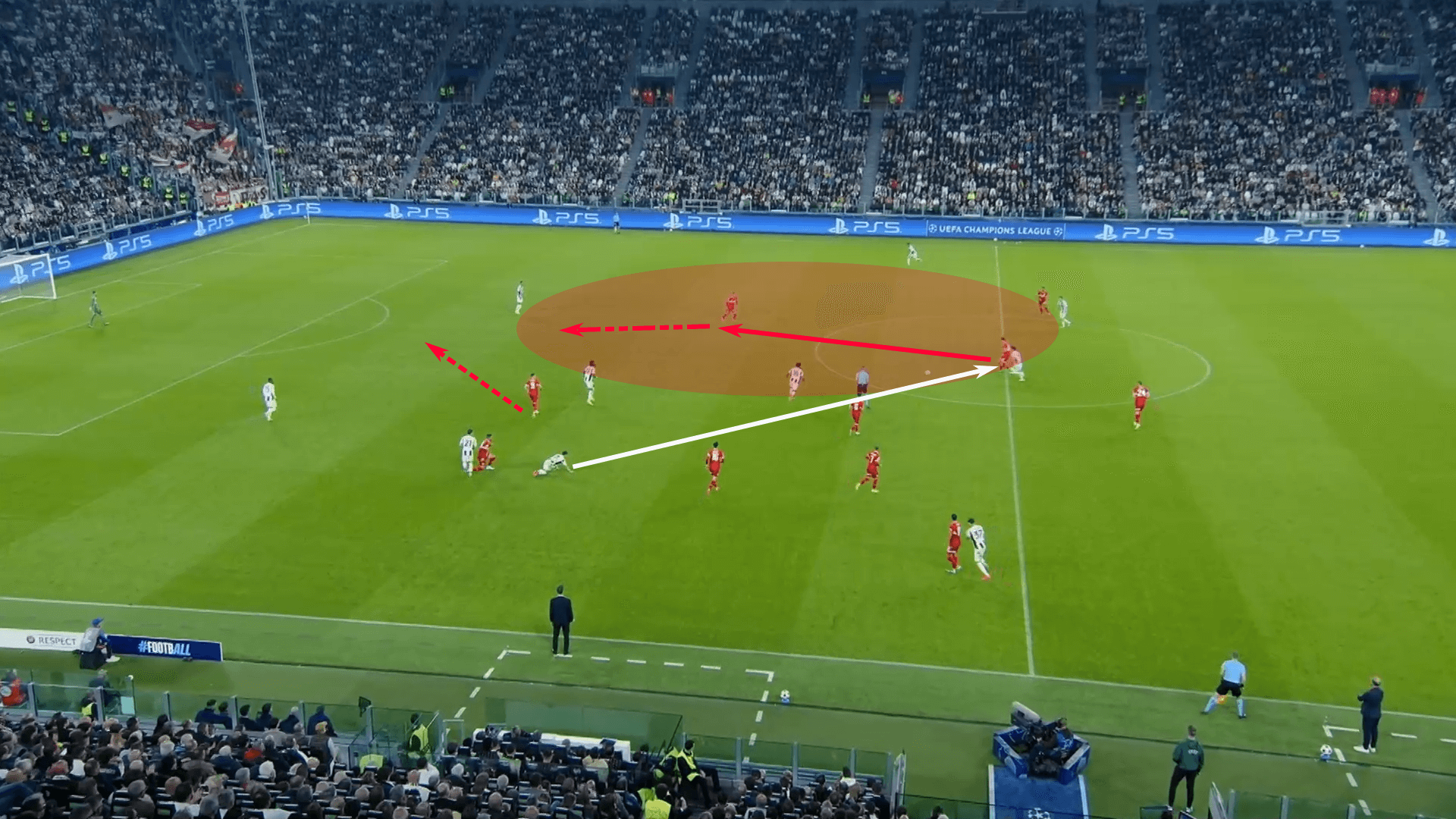

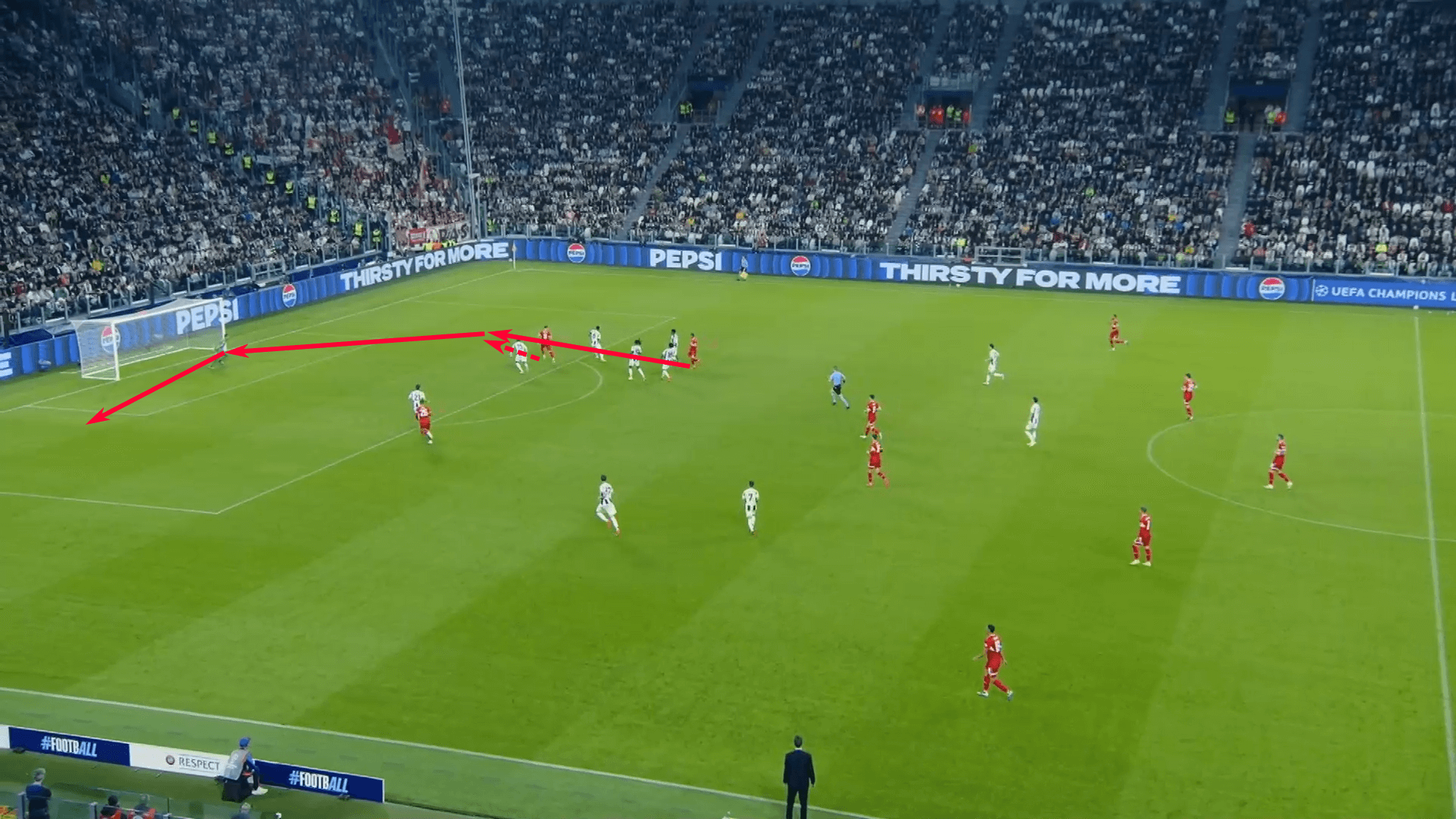

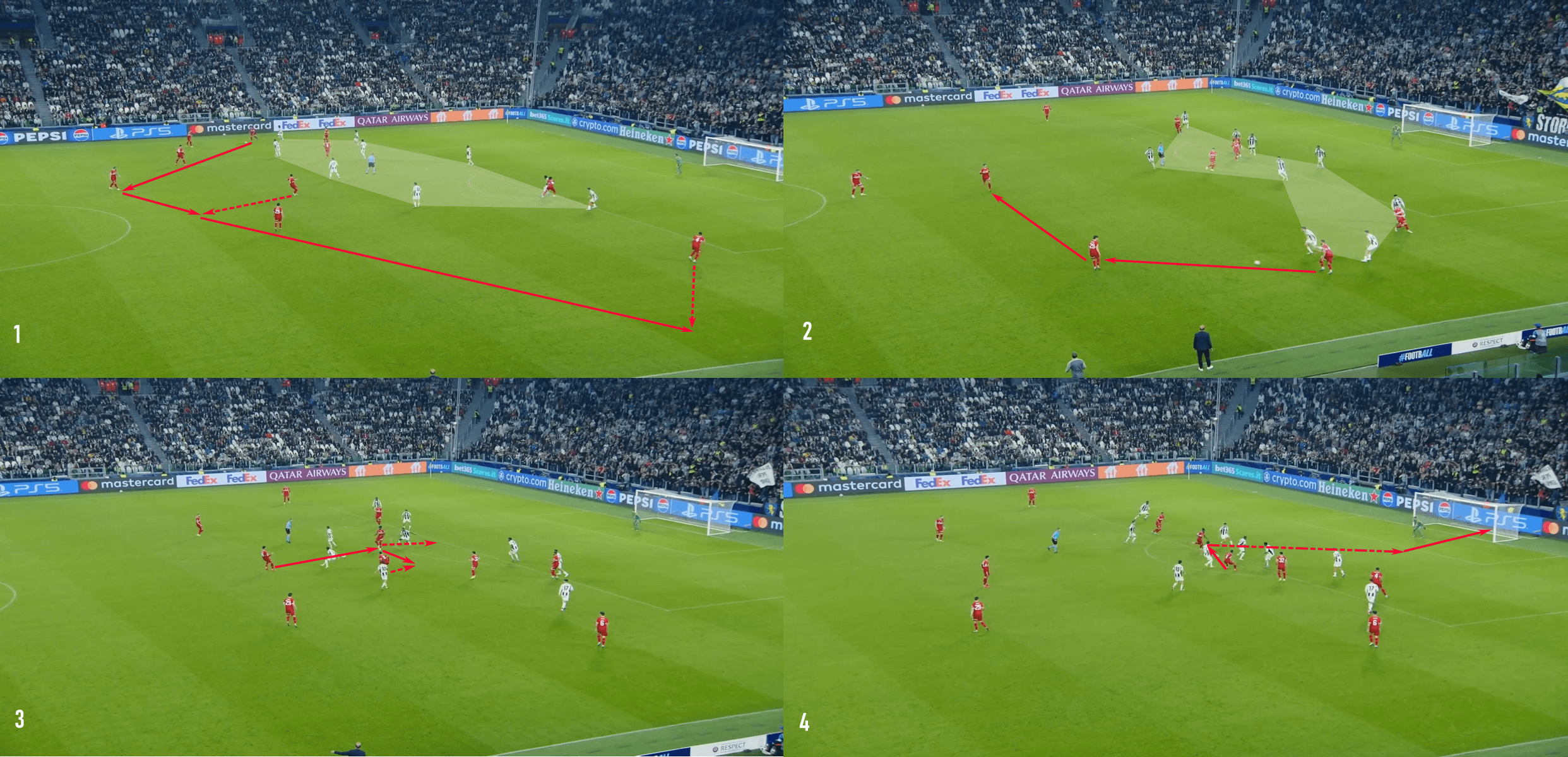

This Stuttgart example comes in the Champions League against nine-man Juventus.

The Italian side has dropped everyone behind the ball in an attempt to take a point from the match.

Stuttgart did well and patiently switched the point of attack to move the Juventus block.

The first two frames show the change in shape as the Serie A side shifted its lines, creating an opportunity to return to the central channel.

With Juventus disorganised, Stuttgart saw their opportunity to play forward.

Their high and central numbers provided the means forward.

With numbers in place, they quickly combined before Bilal Touré glided past the Juventus backline and found the net for the 92nd-minute winner.

Stuttgart showed patience to continue moving the ball from side to side and then played centrally to assess their options against Juventus’ low block, which was key to their success.

Playing into the wings created the opportunity to come back inside against a less organised press.

Our final example is very much in that mould but with an even more condensed pitch.

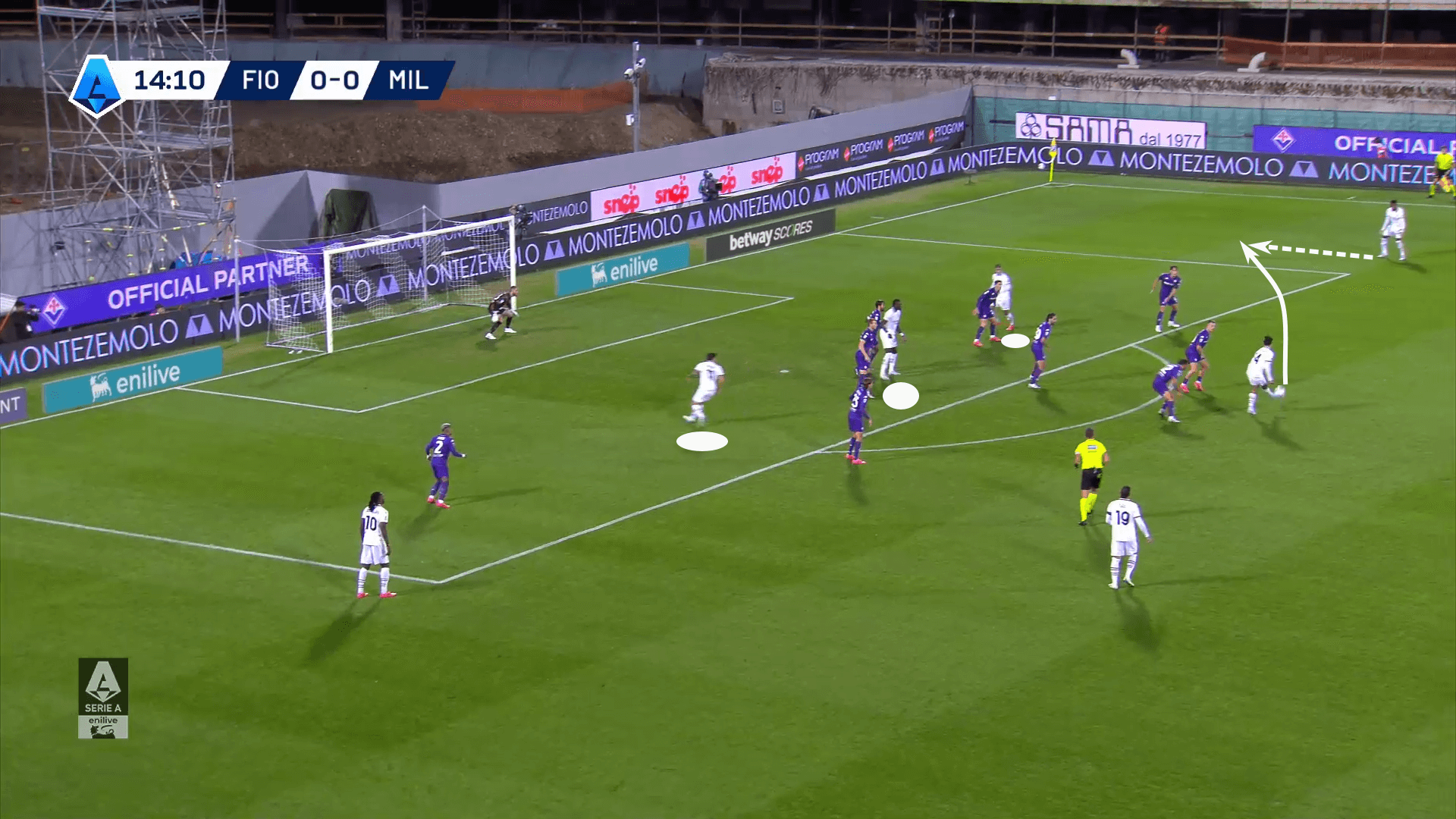

Christian Pulisic was in possession in the right wing and drove inside before releasing the ball to Tijjani Reijnders in Zone 14.

Pulisic’s run compressed the Fiorentina low block, meaning the free player was in the wing again.

The Dutchman played wide into Emerson Royal, who had time to prepare his service into the box.

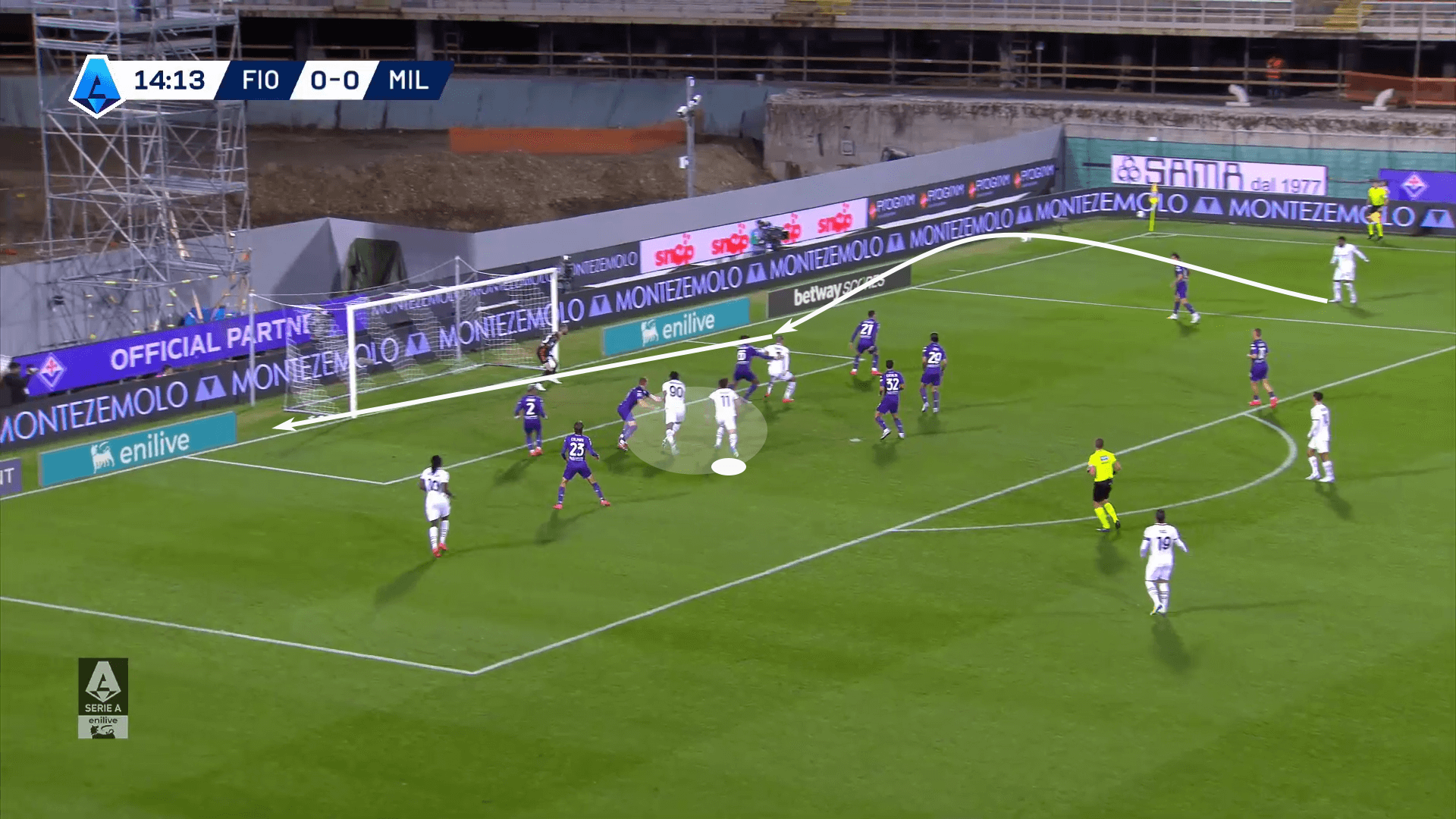

It is noticed that as the ball is played wide, Milan has three players centrally in the box who are preparing their runs to meet the service.

As the cross is played into the box, Álvaro Morata rises to meet it and pushes his header just wide of the post.

It was a good opportunity, but he also had two teammates behind him, including the unmarked Pulisic, who were in a position to head the ball from a better angle while facing the goal.

These high-xG scoring opportunities that played through the opposition press featured a few themes.

First, get someone on the ball between the lines in a forward-facing body orientation.

Second, attack with pace.

That space closes quickly.

Third, if the opponents do compress their shape and take away the path to the goal through the central channel, play wide before coming back in.

Finally, as the ball is played wide, the highest players in the team’s attacking shape must understand that this is their time to make their runs into the box.

Conclusion

If there is another common principle in this analysis of high-xG shots, it is that the first shot or ball through the six often leads to a higher-quality opportunity.

Goalkeepers and recovering defenders often make mistakes, even at the highest levels of the game.

We’ve seen a number of examples of goalkeepers pushing rebounds and crosses directly into the path of opposition players.

Getting players as high as possible and in a position to latch onto rebounds is one of the easiest ways to produce a high-xG scoring opportunity, especially for teams that have pushed numbers forward as they attack against a low block.

As long as the first shot or service into the box forces the goalkeeper into action, the chance of a high-value follow-up will always be there.

The next instalment of this series will examine clubs that take a more balanced approach to their attacking and defensive tactics.

They may not have to beat the low block quite as often, which will surely impact their attack on the box.

Comments