Thomas Grønnemark entered the spotlight as Liverpool announced they had hired a throw-in coach.

A largely overlooked phase of the game, Grønnemark revolutionised re-entries from throw-ins.

His throw-in tactics are centred on the three pillars of long, fast and clever.

Throw-ins are still underutilised in the game, but several teams stand out, especially in the EPL.

You may have guessed, but most of the featured clubs have either worked with Grønnemark in the past or are currently working with him.

This tactical analysis takes a deep dive into throw-in tactics.

We’ll examine each of those three pillars, giving examples of long, fast, or clever throw-ins and the principles at play in these re-entries.

Let’s start with fast.

Fast Throws

Fast throw-ins are an easy way to retain possession or take advantage of an unsuspecting defence.

In most cases, they are played short and back to the thrower or negative to a free man.

Much like a quick restart from a free kick, a fast throw is designed to get the ball back in play with a high, if not perfect, ball retention rate.

But that doesn’t mean they can’t be dangerous.

In fact, that’s how Arsenal was able to claim their first goal against Luton Town.

Gabriel Jesus identified the opportunity to play quickly to Bukayo Saka.

A brilliant stutter step helped him lull his mark, Alfie Doughty, into a momentary mental lapse.

Saka and Jesus took advantage of that mental lapse to turn the corner on Doughty and dribble towards the goal along the end line.

Kai Havertz pulled Gabriel Osho away from the centre with a near post run, and Gabriel Martinelli followed his lead with a movement to the penalty spot.

A simple negative cross and finish gave Arsenal an early lead.

Watch each of the teams in this tactical theory analysis.

As they throw the ball in, the majority will be quick restarts.

Often, they are short and returned to the thrower as an ode to Johan Cruyff or played negatively to the free man.

It’s an easy way for the in-possession team to retain possession.

When opponents fall asleep, it’s also a great way to hurt them with a fast restart.

That’s precisely how the Gunners jump to an early lead.

Long Throws

Perhaps the most famous of Grønnemark’s three pillars, the long throw is a devastating weapon with the right personnel.

First, if there is a player on the team who can reach the middle of the goal with a long throw, like Mads Bech of Midtjylland, the throw-in design options are near endless.

For teams that can only reach the edge of the 6-yard box, there are still set plays that coaches can design to take advantage of a long throw.

The length of the throw will largely dictate where the personnel is positioned.

Especially when a player cannot hit the goal mouth, a primary target area is necessary.

Designating two or three players for that target area will increase the likelihood of winning the first ball.

Then, teams have to fit pieces around those three players.

Assuming the throw does not hit the goal mouth, it is typical to have players within the width of the goal who can play the flick.

It’s their duty to fight for a second ball that can be redirected towards the goal.

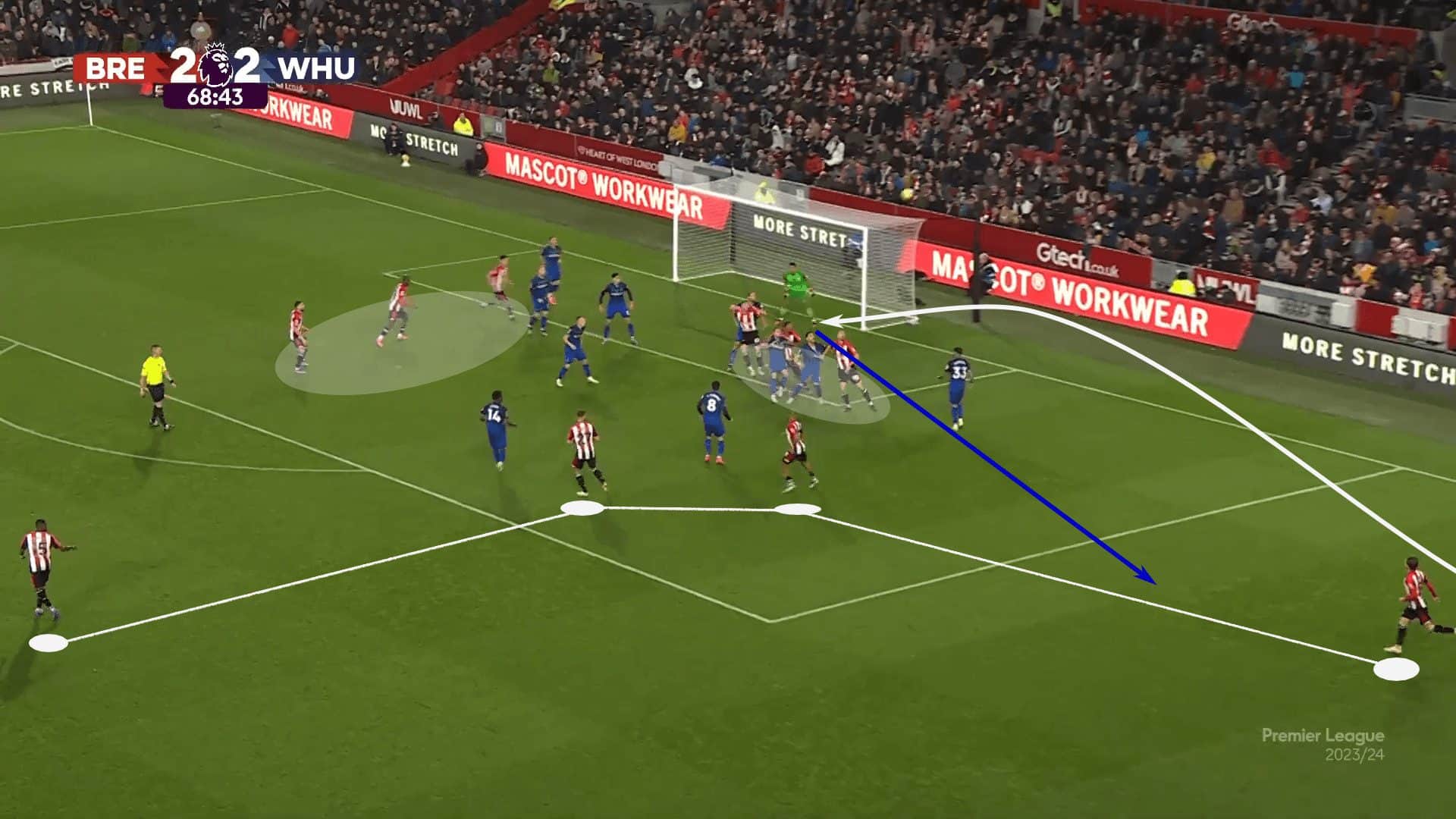

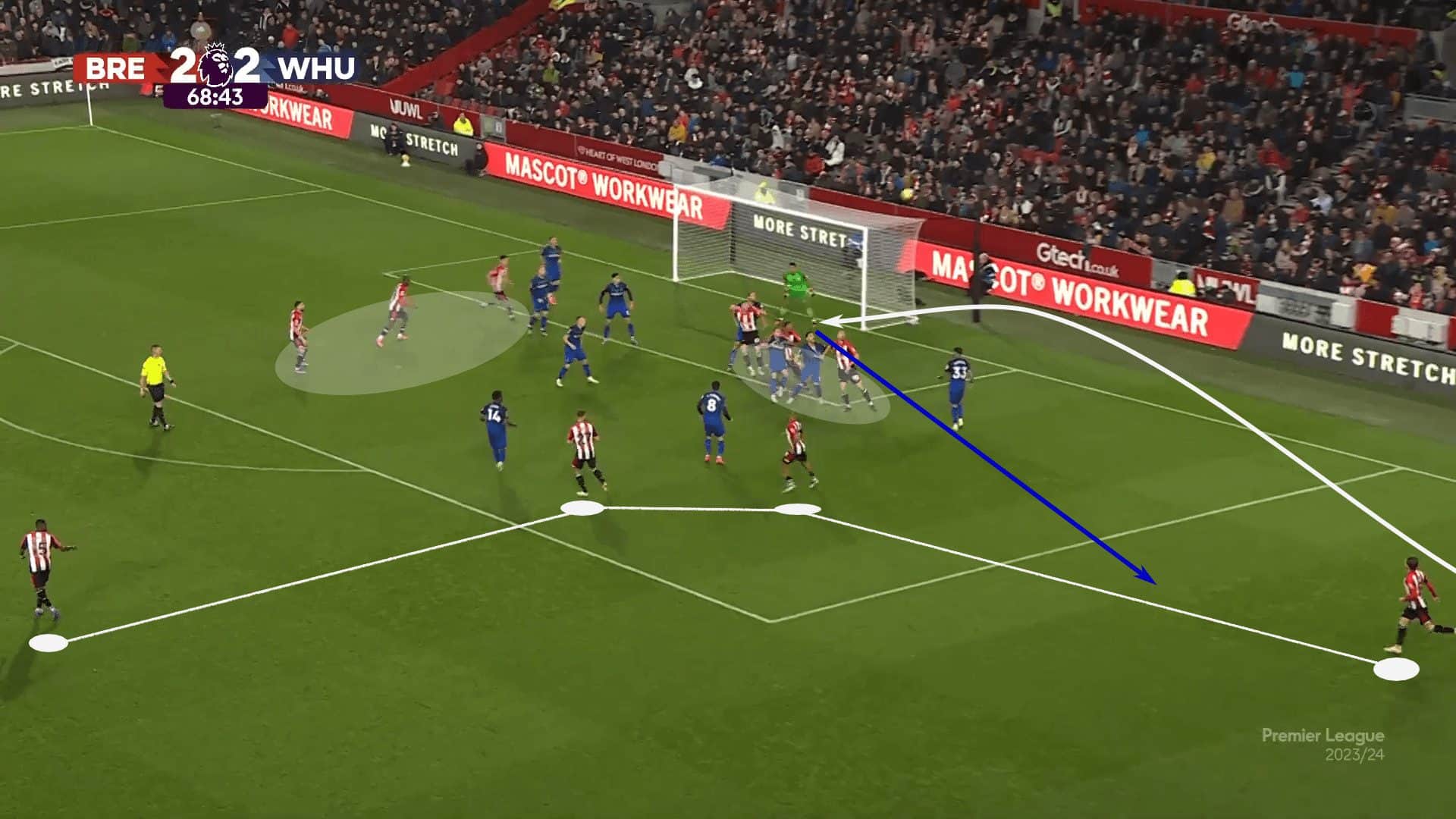

In this Brentford example, the target area is near the corner of the six, and three players are contesting the throw-in.

Three more players are prepared to attack the centre of the goal at varying heights.

Now, look at the remaining four players.

By the way, in case you didn’t notice, every single Brentford field player is in this image.

The last defender is approximately 30 m from the goal.

He, the thrower and two additional players are positioned to attack any second ball that’s cleared out of the target area.

Secondarily, it’s their responsibility to end any counterattacks that emerge.

In this instance, the clearance goes back to the thrower, allowing Brentford to send another ball into the box.

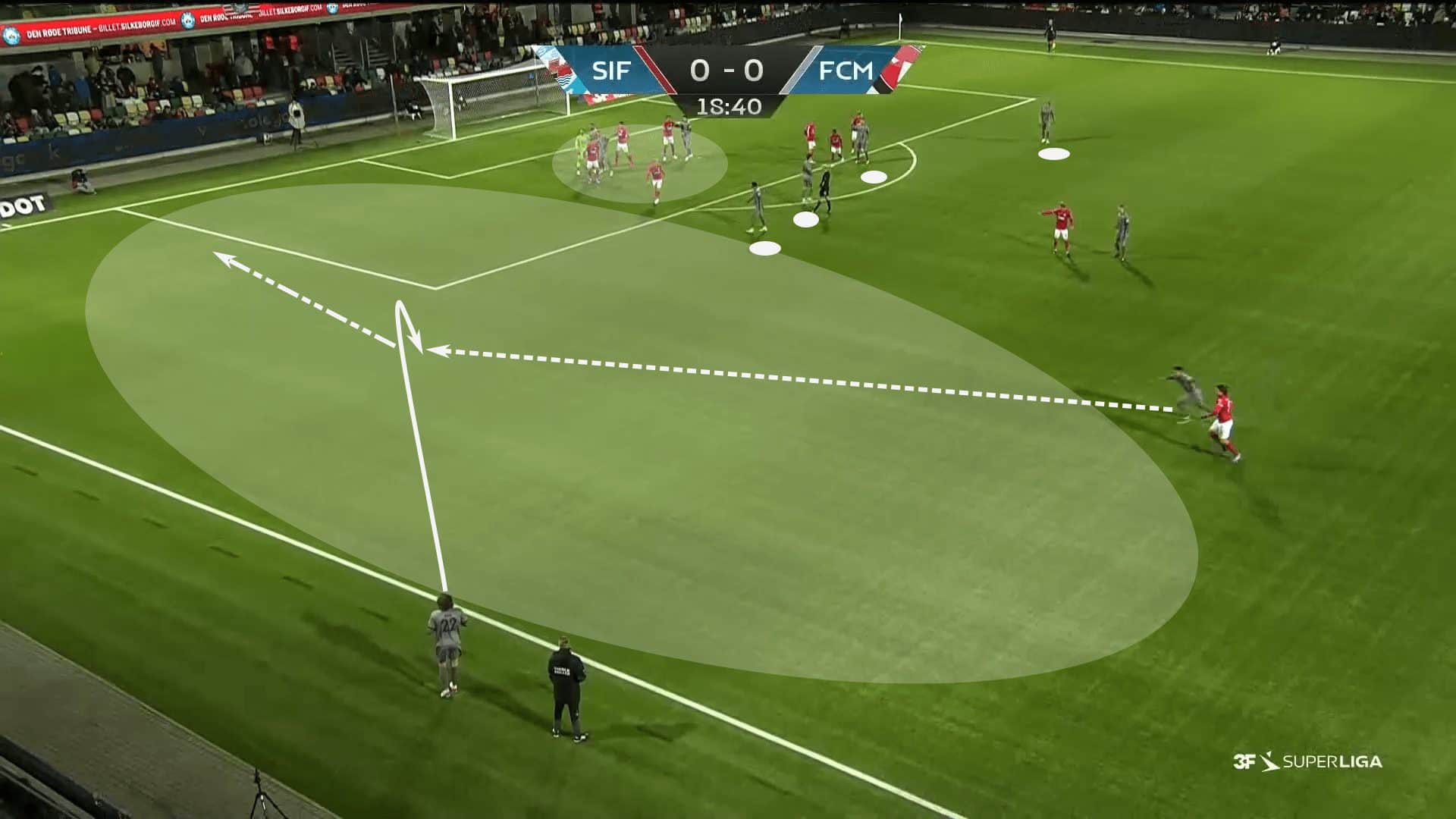

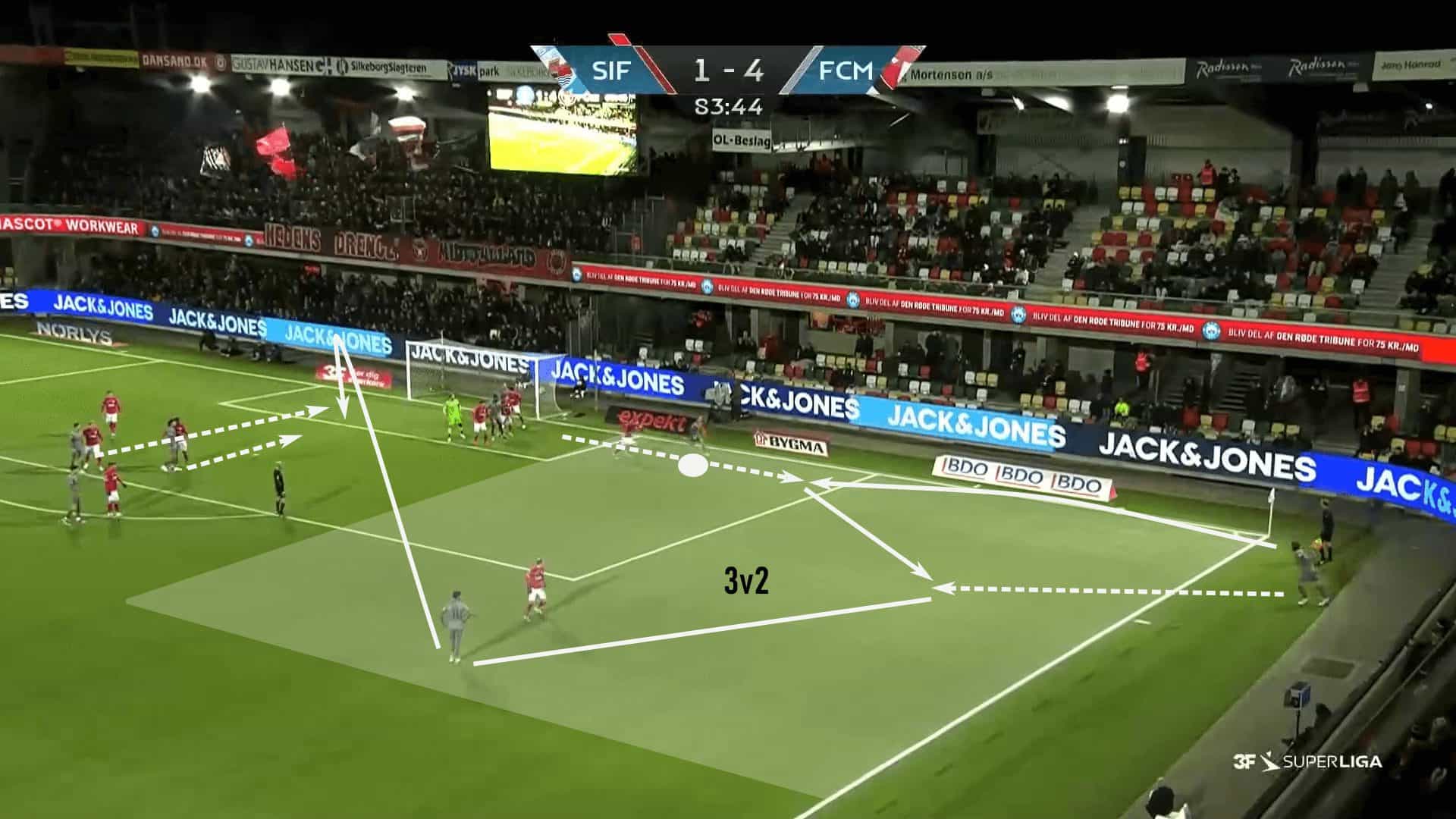

When you have a long thrower like Bech, the setpiece design is tremendously flexible.

In this case, you can see the primary target area shaded near the penalty spot.

Waiting there to contest the long throw, Midtjylland has four players just outside the box who are prepared to challenge the second ball.

That creates a lot of space near Bech.

Paulinho, the last man back, sees the opportunity and bursts into the wing for a short throw.

He collects the ball and delivers a cross from just outside the box.

The head of Sverrir, Ingi Ingason, meets his service, giving Midtjylland the opener in a 4-1 victory.

When a team has a long throw at its disposal, especially one that is thrown in a straight line like Bech’s, rather than a high-looping delivery, the attacking team has an incredible advantage.

Speaking as someone who has had the misfortune of setting up his team to defend against an onslaught of long throws, the defending team must prepare for chaos in the box.

The absence of offsides and the difficulty of clearing a long throw out of harm’s way lead to a lot of first—and second-ball defending.

Additionally, if the attacking team designs the play well, the goalkeeper should have very little room to move.

A long throw like Bech’s is a nightmare for opponents.

Clever Throws

Moving now to clever throw-ins, consider this as a means of reentering play against an organised defence.

When the fast throw-in isn’t available, there’s no real advantage to set up for a long throw-in, especially if the restart comes outside the attacking third.

In these instances, choreographed movements can be used to manipulate the opponent’s shape and create gaps in their press.

A general principle of clever throw-ins is to reduce the area covered by the defending team.

To complicate the execution of the clever throw-in, the defending team is organised near the ball and will assume the throw-in cannot get over them.

If it can’t beat the press, the throw has to go through or into it.

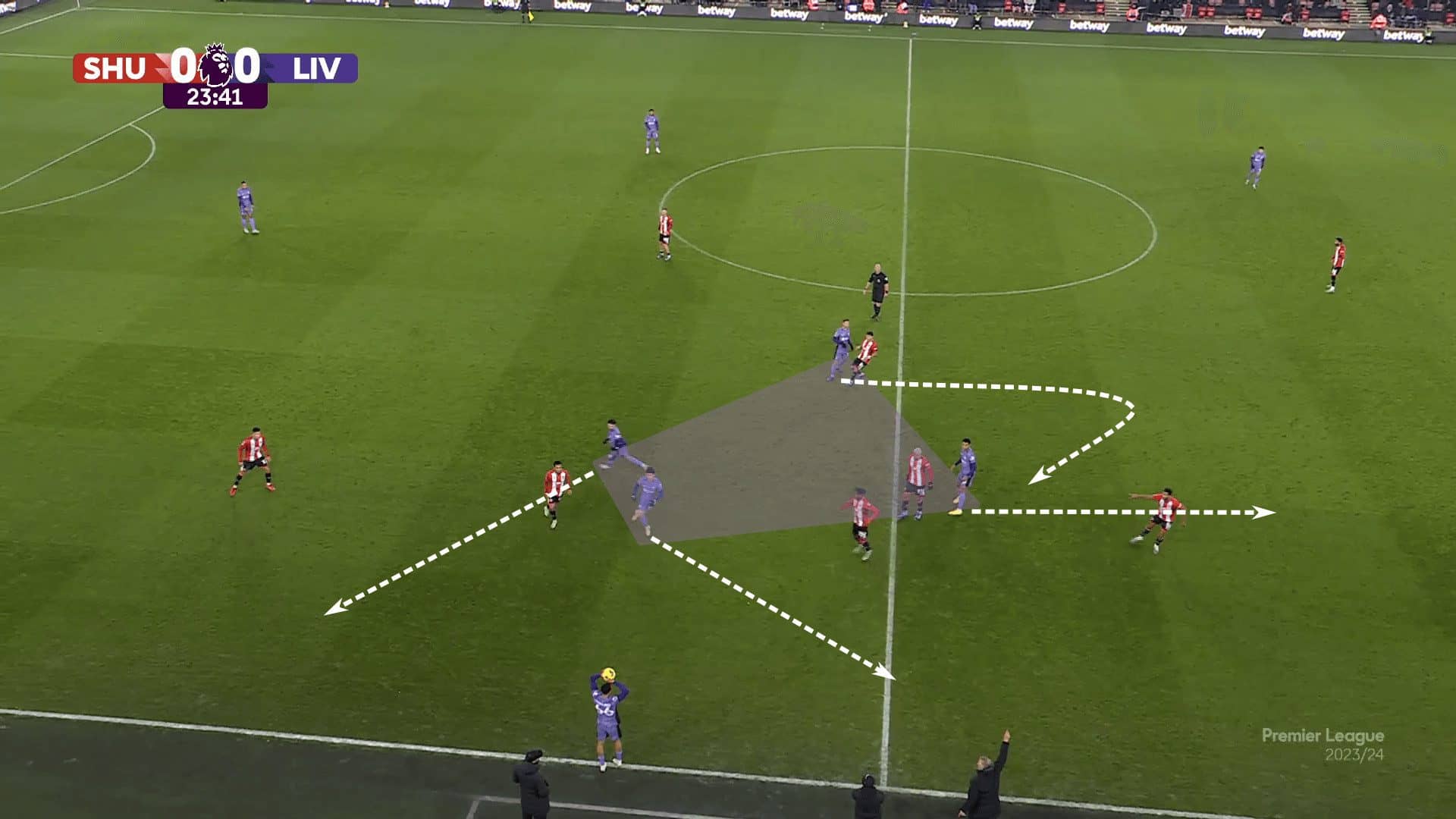

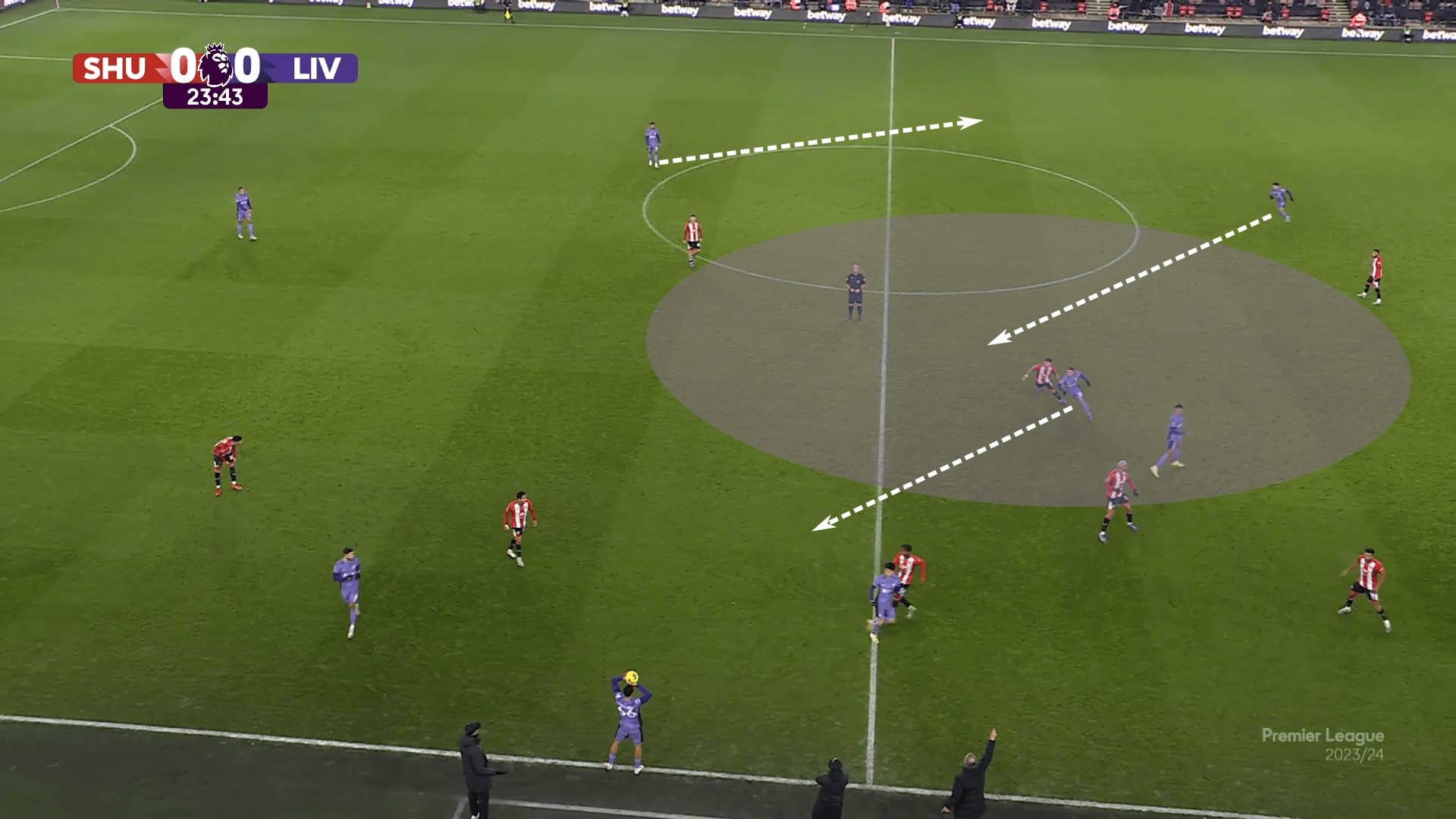

This example from Liverpool vs Sheffield United is a great introduction to the section.

Notice Liverpool’s attacking shape.

In addition to the thrower, five players set the perimeter of their rest defence, and four players showed up to the ball.

Sheffield United has committed six players to defend the throw.

To win this 4v6, Liverpool has some work to do.

To start, the four players near the ball are initially very tightly connected.

Then, three run towards the ball, and one moves higher up the pitch.

Starting further away gives them some space to run into, where they could reasonably receive the throw and set it back to Trent Alexander-Arnold, who could then play the ball out of pressure.

What they didn’t account for was the large shaded area that opened up once the last run was completed.

As Alexis Mac Allister checked to the thrower, Luis Díaz sprinted into the shaded area and received the throw.

He had time to turn and complete the switch of play to Joe Gomez, who effectively took Diaz’s spot in the wing.

Starting further away gives them some space to run into, where they could reasonably receive the throw and set it back to Trent Alexander-Arnold, who could then play the ball out of pressure.

Sheffield United had to defend against that possibility.

What they didn’t account for was the large shaded area that opened up once the last run was completed.

As Alexis Mac Allister checked to the thrower, Luis Díaz sprinted into the shaded area and received the throw.

He had time to turn and complete the switch of play to Joe Gomez, who effectively took Diaz’s spot in the wing.

That’s an example of a clever throw to beat the press in the middle third.

The remaining examples take place in the final third.

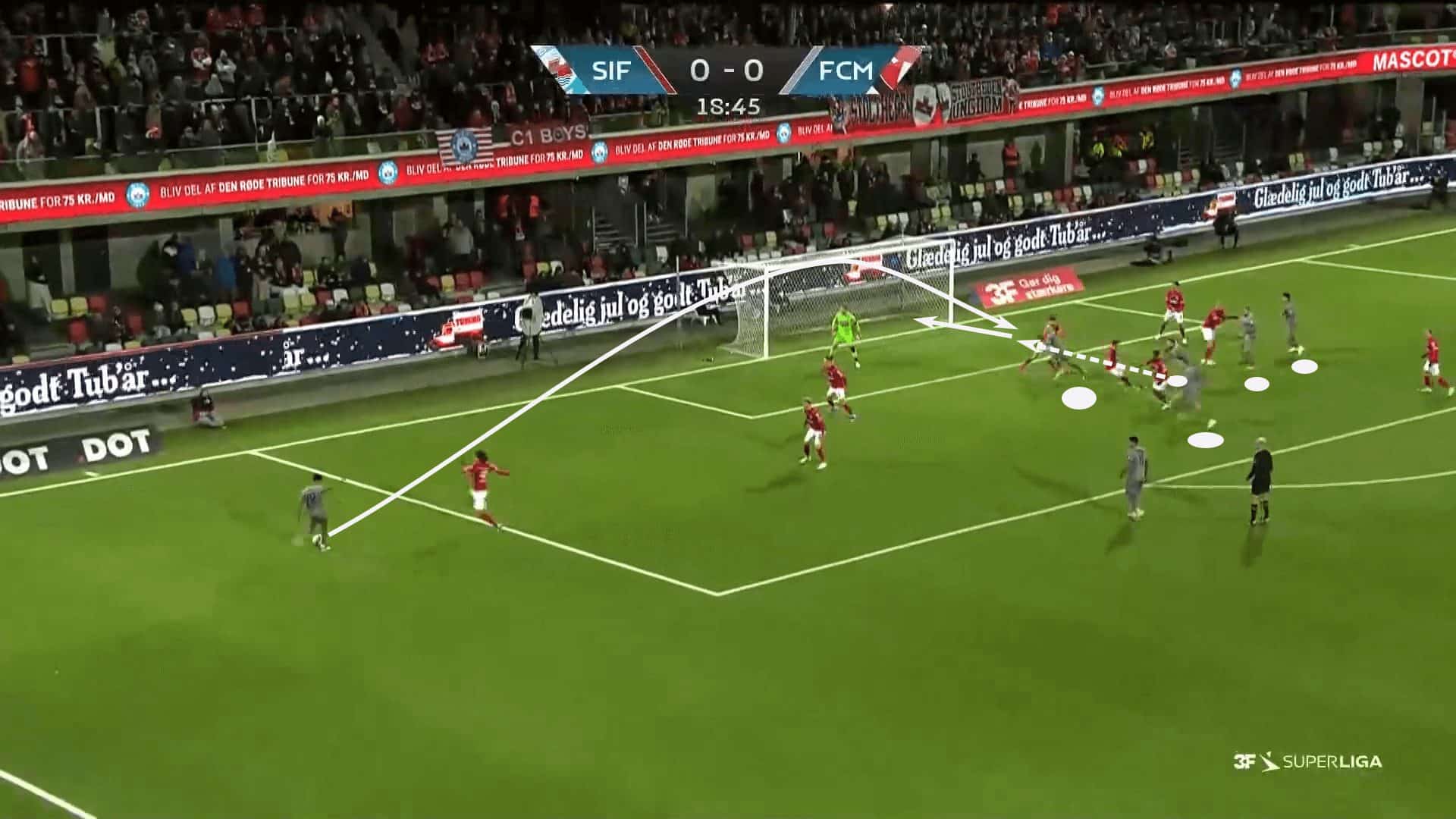

The first comes back to Midtjylland.

As the set piece dynamos set up for the long throw, Bech and Aral Şimşir looked for an opportunity for a fast, short throw.

As Şimşir walked away and Bech took his position for the throw, they broke eye contact, but their eyes were fixed on the same target.

Watching the movement of Nordsjælland’s Mario Dorgeles.

The moment he turned to look at his side’s organisation in the box, the short throw was played.

The service didn’t connect with a runner, but the execution up to that point was superb.

Midtjylland had three players in the box crowding the keeper and four players near the 18.

As the throw was played in, the three who stacked the six-yard box dropped with the defensive line and were joined by two players from the top of the box, giving the home side five players attacking the service.

It also ensured the runners were moving towards their goal, ensuring better momentum and power as they looked to finish.

Brentford gives us another short throw.

Initially, they recognised the three players at the far post commanding Luton Town’s attention.

Then there are two more players at the top of the 18 in the half-space, drawing more players away from the wing.

Ultimately, Luton Town goes man for man in the wing.

Brentford sees the 3v2 opportunity and plays short.

The ball is set back to the thrower, and a simple give-and-go helps them win the encounter and get a service off.

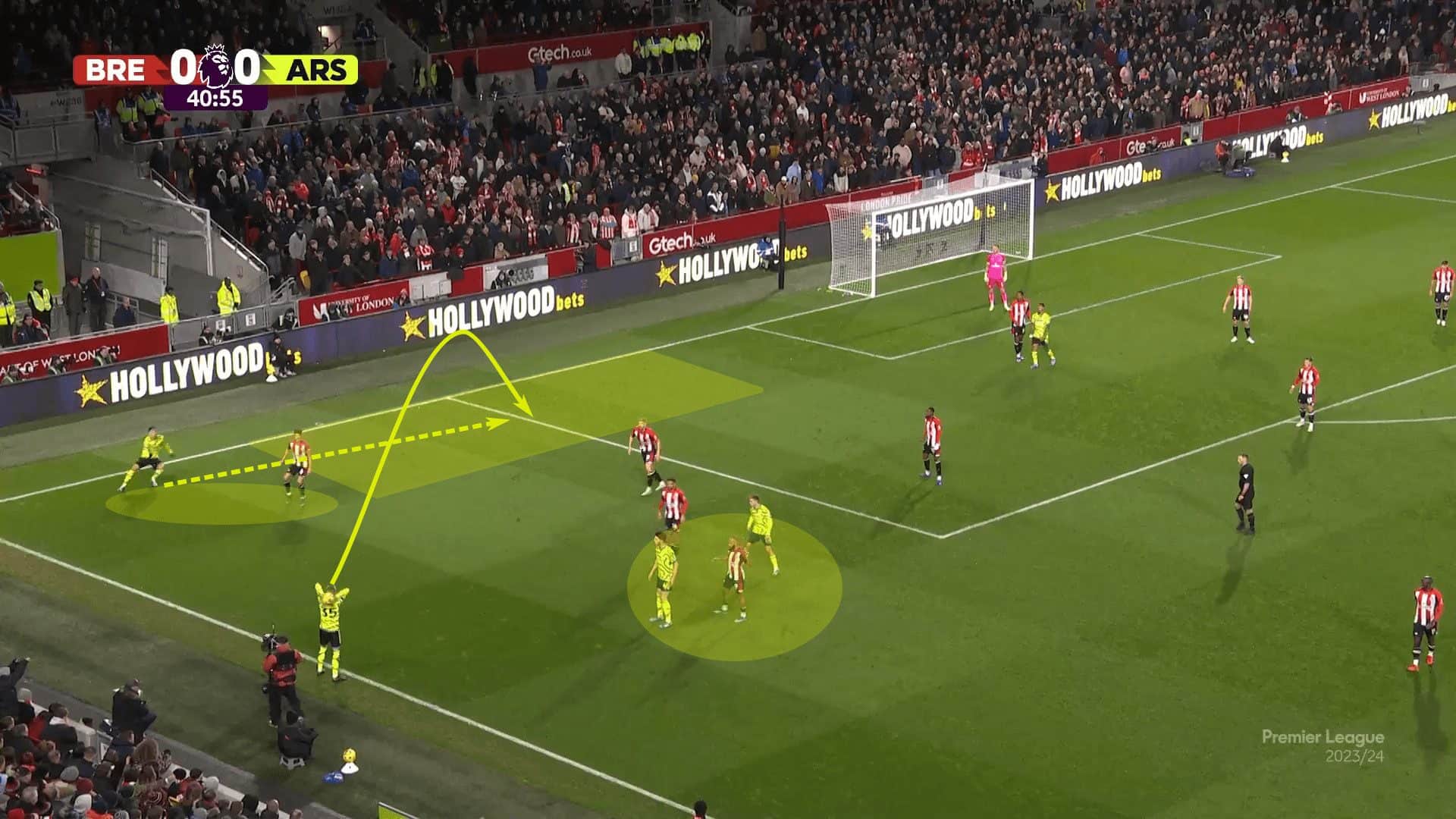

We’ll come back to Brentford for this following example, but in this case, they’re on the wrong end of the throw-in.

Arsenal didn’t bring many numbers forward in this instance, but they did send three near the ball.

Two of those players are tightly connected in an attempt to draw the free Brentford defender towards them.

And they succeed in doing so.

As he steps forward, the throw is played into the low corner of the box.

Arsenal eventually puts the ball in the back of the net in this sequence, but further down the line, an offside call negates the goal.

One important note here is that Oleksandr Zinchenko is in no rush to throw the ball.

He holds it for about 10 seconds before throwing it to Martinelli.

As he holds the ball, there’s a lot of movement from the three Arsenal players near the ball.

First, their spacing is evenly distributed across that area, but then the two men overload near Zinchenko, which gives them the visual cue they’re looking for.

That’s the signal to throw the ball.

Finally, let’s head back to Denmark for our last long throw.

The brilliance of this sequence is capitalising on the fear Bech strikes in opponents.

With his long throw, the 30-metre square nearest him is largely abandoned.

Seeing the space, Joel Andersson makes his move.

He leaves the goal-mouth, checking towards Bech and receiving the throw.

He sets to Bech, who plays out of a 2v2 to Darío Osorio, who found a pocket of space once his defender left to pressure Bech.

The service missed the far post runners, but this clever creation of a 3v2 did its job.

Midtjylland had a clean look at the service into the box with three players in position to meet the cross.

Conclusion

Tomorrow, 12 December, happens to be Grønnemark’s 48th birthday.

The timing of this tactical analysis is a coincidence, but knowing tomorrow is a day of celebration, we at Total Football Analysis wish Thomas Grønnemark a happy birthday and thank him for his impact on the game.

The three pillars of long, fast and clever throw-ins are largely common knowledge in the coaching world because of Grønnemark’s work, but throw-ins are still in an underutilised phase of the game.

If the examples presented in this analysis sparked your interest, make a concerted effort to pay close attention to throw-ins as you watch these clubs.

Go the extra mile as well.

Start designing your own throw-in playbook.

Using the long, fast, clever framework, design ways to retain the ball through throw-ins with each of those approaches.

Fast is relatively straightforward and long is often very similar to corner kick design.

Long and clever throw-ins are great places to start to get your team out of pressure or create goal-scoring opportunities.

Comments