The efficiency and intelligence of the modern game is quite astounding.

Positional play has produced extraordinary levels of synchronicity within teams. The very best teams…the only word to describe their play is “mesmerizing.”

As a response, pressing has dramatically improved in recent decades. Because of the ease with which teams attacked space, there was a necessary move to become more organized and reduce the amount of space available for the opponent to attack.

The game has reached a remarkable height, but there is one shortcoming.

We’ve lost our entertainers. The players who produced moments of individual brilliance every time they stepped onto the pitch are few and far between. The magician, who often demanded degrees of freedom within the team’s tactics, has lost his spot to the detailed, pressing player and his safe, high-percentage/low-risk passes.

Tactical progression has conspired against the magicians, but exceptional entertainers have survived the turn of the tactics. Vinícius Júnior of Real Madrid is perhaps the most notable, but he’s not alone. The EPL’s Kaoru Mitoma and La Liga’s Takefusa Kubo are masters of the duel. They’re the type of players who command our attention every time they touch the ball.

Those are the individuals who entertain us most. But we need more of them. This tactical analysis will aim to see what makes these masters of the duel so special. This tactical theory piece will put forward three principles of 1v1 attacking, give examples from Mitoma and Kubo and provide an exercise to train each of these principles.

Support your local dribbler and help the cause by developing more. Let’s get started.

Creating and reading a physical imbalance

Too often, when 1v1 attacking is taught, the focus is strictly on the attacker’s actions. Can you get in and out of a step-over fluidly? How about a Ronaldo chop or an elastico? Perhaps a simple insider or outside chop?

Having the skill set to execute these moves is important. It’s the foundation of 1v1 attacking. Without the skill set to get in and out of these moves, you’re simply not going to pull them off.

But it is just that…the starting point. The issue with only training these moves without the additional context of defenders to beat and space to attack is that the player will only find success against defenders lacking 1v1 defending technique. Deception to draw the opponent into a physical imbalance is necessary, but so is the understanding of when imbalances are present.

This is where Mitoma and Kubo can help us. In watching their 1v1 attempts, we see that they’re not simply making a move and hoping it works. Instead, their physical actions are designed to provoke an imbalance in the opponent’s body orientation. To create the imbalance is one thing, but to see that slight shift is another. Having awareness of the opponent’s physical balance or imbalance is perhaps the most critical aspect of the duel.

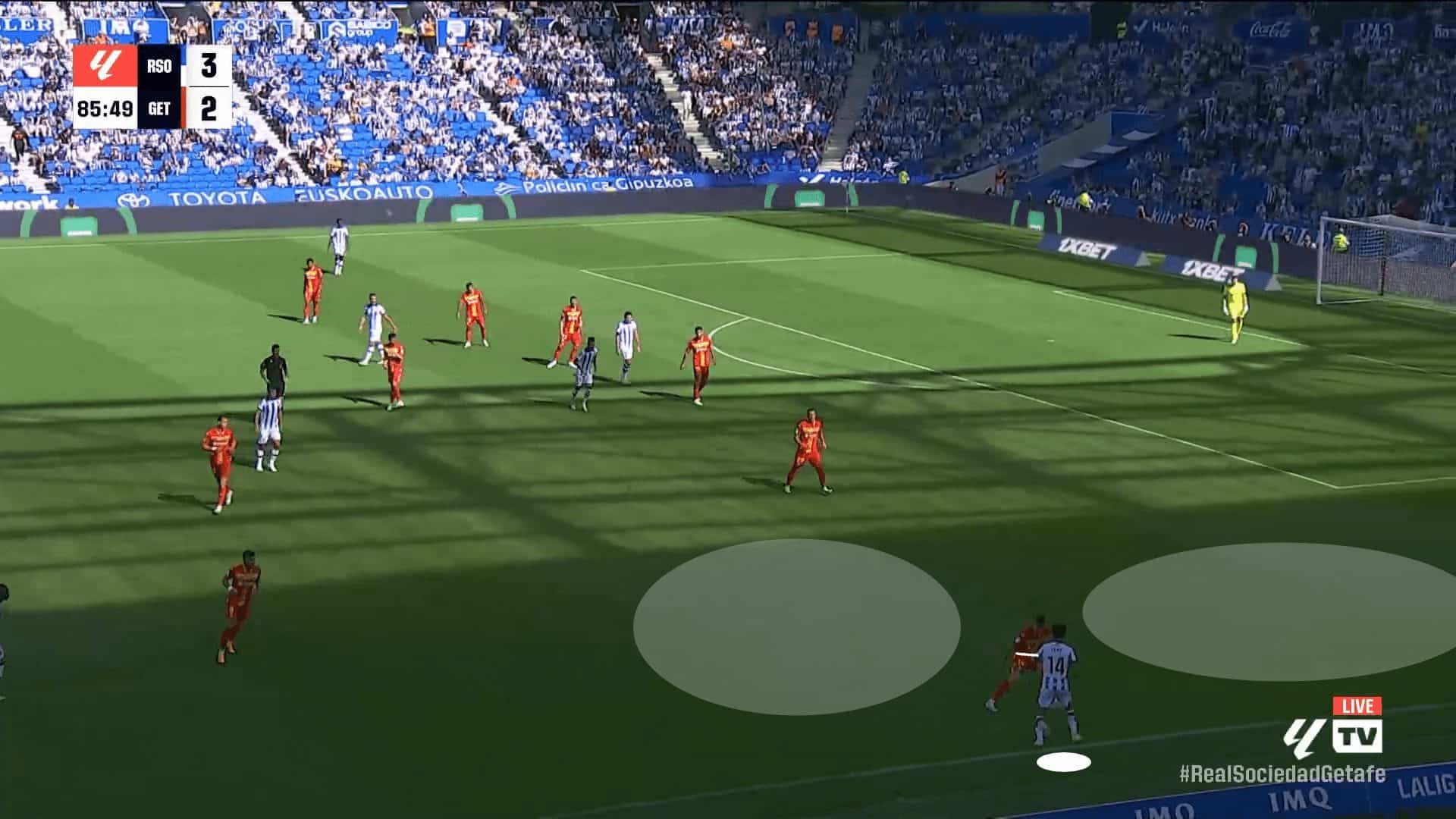

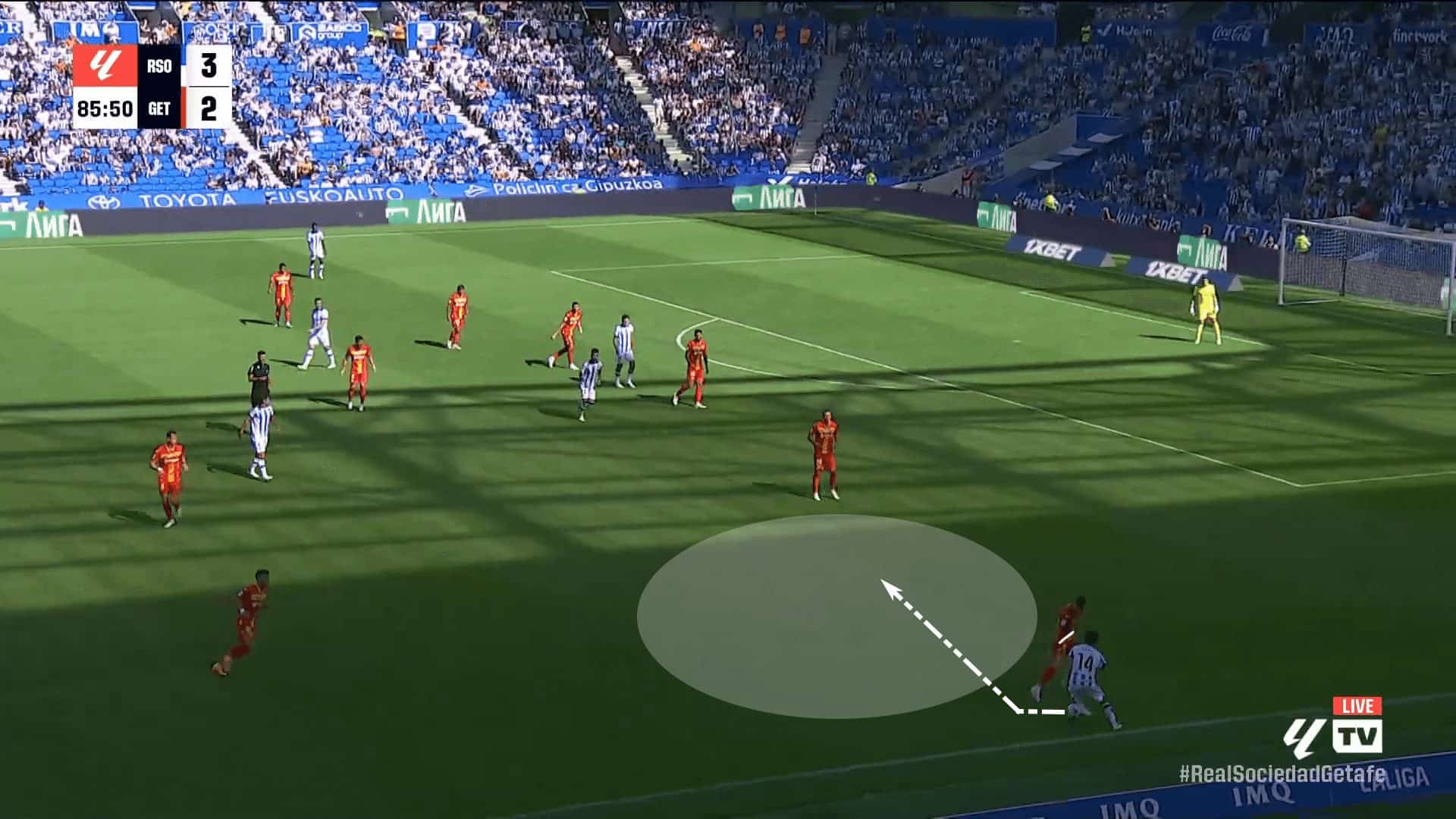

Whether at a moderate pace or standstill, the two Japanese internationals understand how to bait the opposition into an imbalance and know when to make their move. Against Getafe, Kubo held the ball in the right wing with his opponent attempting to force the duel down the line. Kubo still sees space to the left or right, but he also sees that the opponent’s hips are square to him.

To make his move, especially to his preferred left foot, Kubo starts the duel by moving the ball up the line. That’s exactly what his opponent wants. Thinking he’s got Kubo pinned to the touchline, the defender’s hips turn towards his end line as he braces for a race.

That’s when Kubo knows he has the defender beat. As the defender’s hips turn, Kubo can cut the ball back towards midfield and then dribble inside. With the defender’s hips moving in the wrong direction, he’s unable to adapt and catch the Real Sociedad star.

In another La Liga match, this time against Mallorca, Kubo had his opponent on skates. While dribbling at his opponent, he made a couple of moves to disconnect his opponent’s feet and get his hips moving from side to side. The defender had no control over the duel; he reacted to Kubo’s movement. The visual cues that Kubo recognized were the defender’s hips set well behind his feet. That indicates that the defender was leaning backwards and would be unable to quickly respond to Kubo’s acceleration.

Also, look at the relation of the defender’s knees to his toes. The toes on each foot are far out in front. This is just another indication of the defender’s poor balance. Once Kubo touches the ball by him, it’s an easy win. The defender is already beaten, so now it’s merely a matter of accelerating past him.

In each of these examples, as well as the ones to follow, notice both the imbalance of the defender and the largely balanced stances of the attackers. In order to win the 1v1 duel, the attacker needs that quick change of pace to accelerate past his opponent. To make that happen, he must push off from a balanced position.

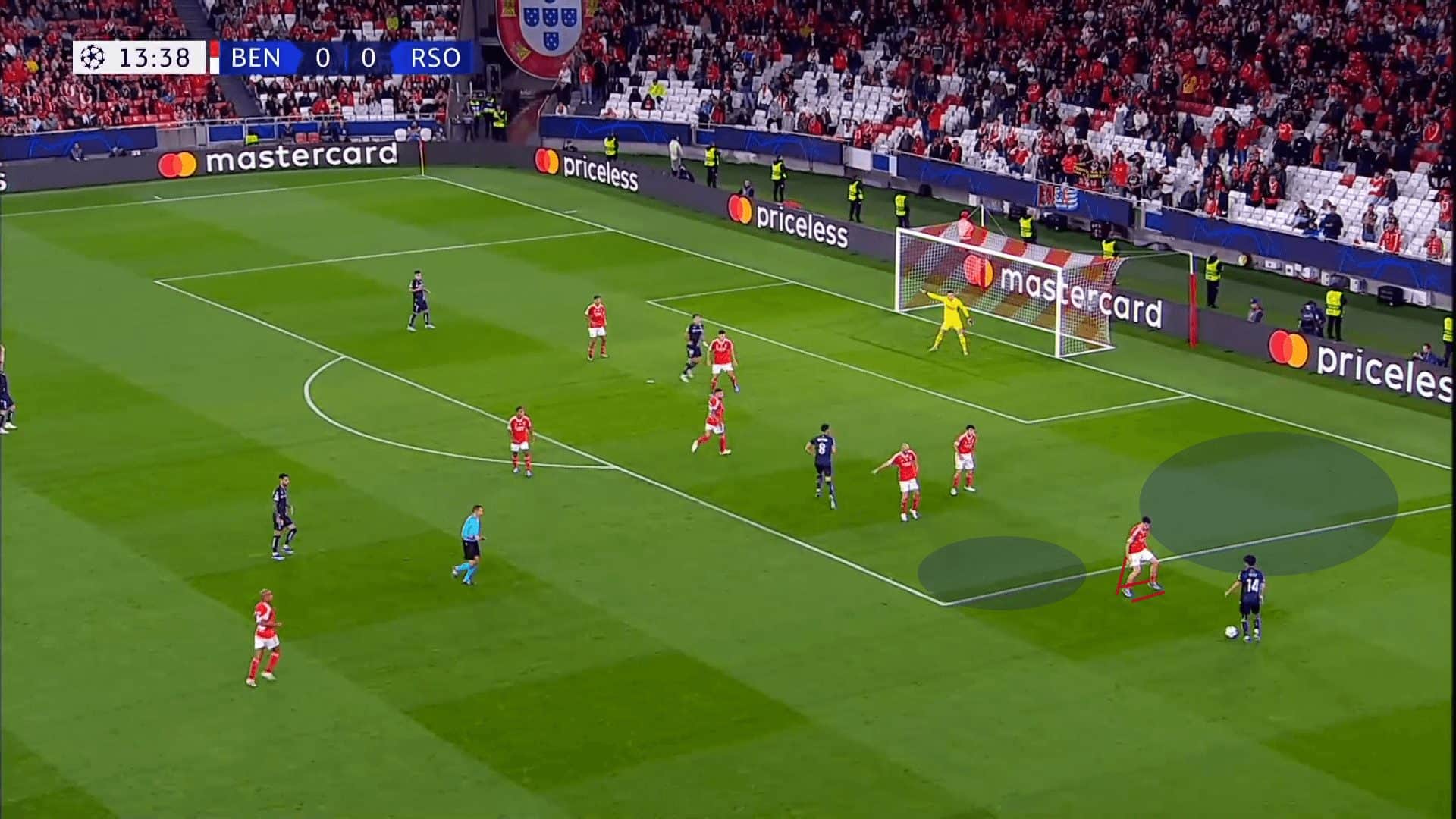

The final example of creating and reading a physical imbalance in the opposition comes from Champions League play as Kubo relentlessly attacked the Benfica backline. In this instance, there’s once again space to the defender’s left and right. Notice that the Benfica cover defenders are prepared to shift into a first-defender role if Kubo moves to his preferred left. Rather than forcing the issue, Kubo positions himself to make the defender think he’s going left before going right. With his quickness advantage, he easily wins the duel.

Looking at the lines tracing out the Benfica defender’s weight distribution, there are a few things to note. Once again, his hips and chest are behind his heels. Kubo has backed him into an unbalanced body orientation. Second, the defender is square to the attacker.

Though the intention is to be able to defend to the left or right, depending on the attacker’s move, this square positioning shows the defender is at the attacker’s mercy. He is waiting to react to the attacker’s move. Against a quick player like Kubo, the defender will lose every time. The defender’s positioning and weight distribution lead to poor footwork as well. He’s unprepared to quickly move in a given direction.

Part of the issue with his footwork is that it corresponds to not knowing where Kubo will go next. As the defender, the goal is to dictate where the opponent can go and influence when he will take his action. The Benfica defender is completely at Kubo’s mercy.

I often tell my players that 1v1 duels are a battle for balance. Whoever loses theirs first will lose the encounter.

To train our players’ vision, understanding of balance versus imbalance and knowing when to make their move, we’re going to start without the ball. Rather than directing our attention to the ball, we want the players focused on the movements of their opponents.

The setup is very simple. Create a two-meter zone and then mark off another 10 m from each of those cones, one to the left and one to the right.

The players will alternate turns as the attacker and defender. The attacking player can move anywhere within the 2 m zone, but once he crosses over the cone, he must commit to running to that side. So, if he crosses that right centre cone, he must continue his run to the cone on the right. Once the attacker chooses a side, it is a race between the two players to reach the far cone.

As mentioned, do this without a ball first. This is your opportunity to discuss where your players should look while they’re attacking.

When the defender is prepared to engage in a 1v1 duel, he is balanced, limiting the space his opponent can run into, influencing the timing of the duel and is prepared for moves that cut back across his body. As the attacking player, take those things away from him.

The big tells are the defender’s weight distribution, his uprightness, and the synchronicity of his feet as he moves. If the defender has shifted his weight too far to his front foot or his back foot, it’s time to make your move. If the defender is too upright or his knees are bent too acutely, slowing his ability to respond quickly, make your move. If the defender’s feet are out of sync, the movement between the two is too choppy so that the feet are almost touching as he moves, or the defender is dancing from side to side, showing no control over the attacker’s direction, making your move.

These are some of the core principles of 1v1 attacking, most of which transfer to this simple exercise. Emphasize that 1v1s are a battle for balance. Once your player has the defender off balance, she should make her move. Training the understanding of the relationship of balance to timing is central to 1v1s. If the players are looking for the right information, they should better understand that their moves are not for their own sake. Rather, they’re to provoke a physical imbalance in the defender.

Do this without the ball at first to train vision and awareness, but then add a soccer ball and watch how that changes the exercise. The races are a little bit tighter as the attacker now has to take the ball with him. This is also an opportunity to talk about the first touches out of the duel. If touches are too small, the defender will win. Too big, and the attacker won’t get a touch within that 10 m zone, which will often lead to a loss of possession in a game. Make sure the players get one touch in that 10 m zone so they can’t cheat the system. The first touch out of the 2 m zone should give them a chance to take shorter, accelerating steps, and the second touch should help them open up their stride as they sprint to the finish.

Tempo and timing

There was undoubtedly an element of tempo and timing in the last section, but this is such a critical component of 1v1 duels that it’s worthy of its own section. In any 1v1 attacking move, there has to be a change in tempo at the right moment. The two elements of the duel are so closely intertwined that we wouldn’t dare separate them in this section.

Thus far, we’ve seen examples of Kubo initiating the duel from both a standstill and with the ball in motion. Part of tempo in any 1v1 duel is acclimating the defender to one speed of play, then looking for poor footwork or physical imbalances to trigger an accelerated attack. If the attacker is quicker than his opponent, there is some leeway in the efficiency of his move and timing. The closer the physical matchup or if the defender holds the superiority, such as we’ve seen with Vinícius Júnior attacking Manchester City‘s Kyle Walker, then the deception necessary to cause the imbalance or the change in tempo to catch the opponent off guard is all the more critical.

It’s important to remember that change of tempo is also a form of deception. It takes a different form than feints and other dribbling moves, but the deception is present in the sense of timing in the engagement.

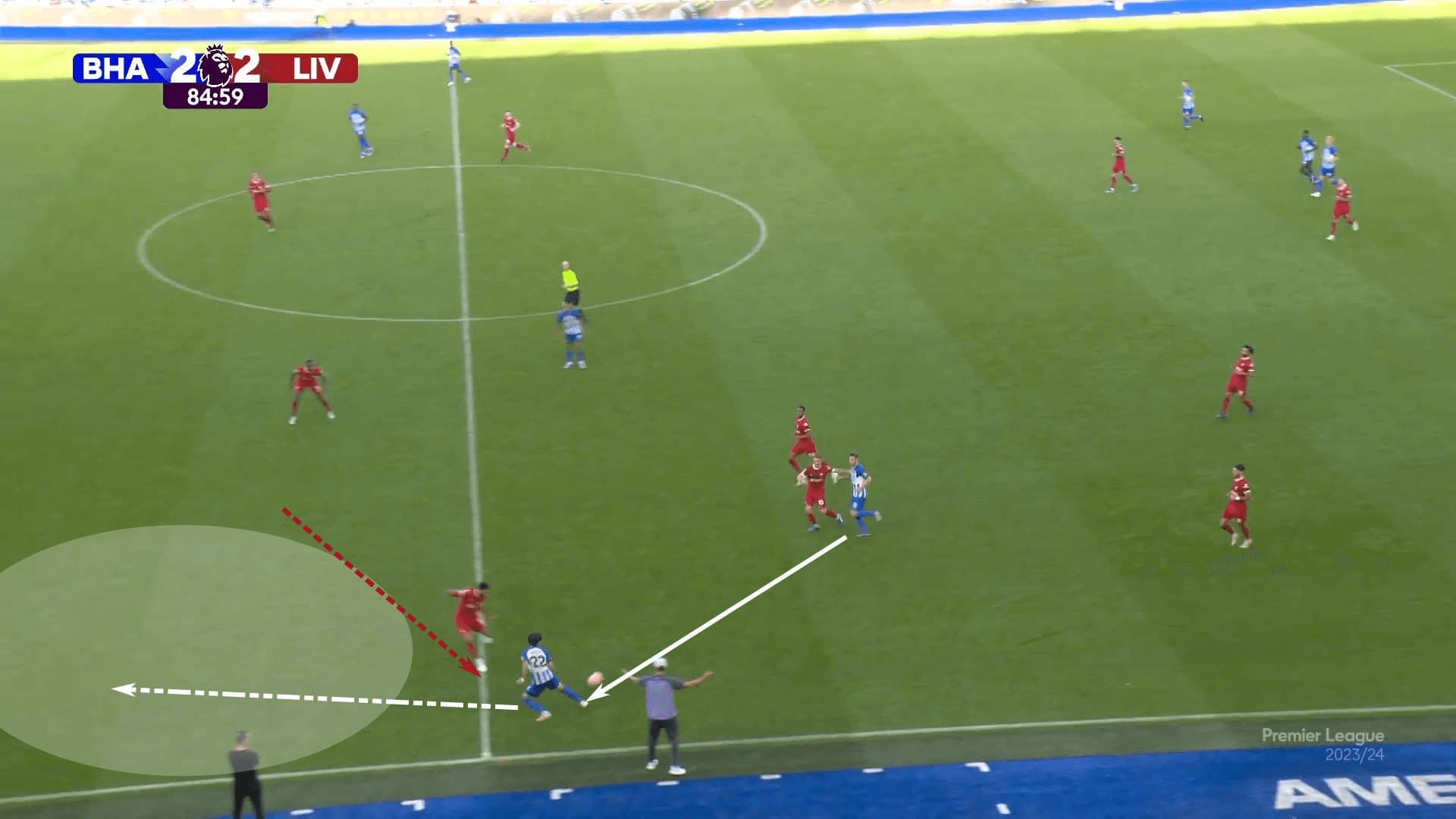

We have a great example of tempo as a form of deception with Mitoma. Mitoma is just waiting for Joe Gomez to commit as the pass comes into him. Mitoma’s approach is brilliant. By waiting for the ball on his near foot it gets Gomez to believe that the intention is to go backwards or cut inside. Gomez believes he’s prepared to deal with the following action, but Mitoma eloquently carries the ball across his body with his right foot, past the extended leg of the off-balance Gomez.

This is where Gomez’s momentum plays a significant role in Mitoma’s decision. The Liverpool man is prepared to continue forward or move to his left. Thinking that his right side is inaccessible, he is not prepared to move in that direction. Mitoma reads this brilliantly, pushing the ball past Gomez, whose off-balance lunge is not enough to stop the ball.

That allows Mitoma to run at the next defender, Ibrahima Konaté. Notice that Mitoma does not run directly to goal. In fact, he almost runs in a straight line along the wing. That draws the centreback, Konaté, out of the half-space and into the wing, away from Virgil van Dijk’s cover. With Konaté running on a diagonal towards the wings, Mitoma lets his opponent run in front of him, then cuts inside behind him. The move allows Mitoma to use his opponent’s momentum against him. Now the forward is running into free space, requiring the recovering Gomez to take the tactical foul just outside the box.

The final sequence in this section offers a close-up of Kubo in a duel against Aleksa Terzić. Let’s look at the defender for Red Bull Salzburg’s preparedness. His feet are in an excellent position, ready to run or plant on his left foot to change direction if Kubo tries to cut across to the inside. Kubo wisely acknowledges that the timing is not on. He still has to create the imbalance to make his move.

Though the defender’s initial footwork was excellent and balanced, Kubo threatens a change of pace. As a result, the defender’s footwork opens up at the wrong time. He wrongly read the timing of the duel and extended his stride to run with Kubo. With the Real Sociedad forward feigning his attack, he forces the defender to slow down.

By the time the defender can slow down, his balance is entirely on his front foot, with his knees well out over his toes, showing the inability to deal with Kubo’s feigned change in tempo. Even his hips are out of balance, with their right side lower than the left. Seeing the physical imbalance, Kubo knows that it is now time to accelerate past his opponent.

The first exercise in this article worked on reading the physical cues of imbalance. Now, it is time to challenge the players to create these imbalances through deceptive movements on the ball and the use of tempo, feigned or real.

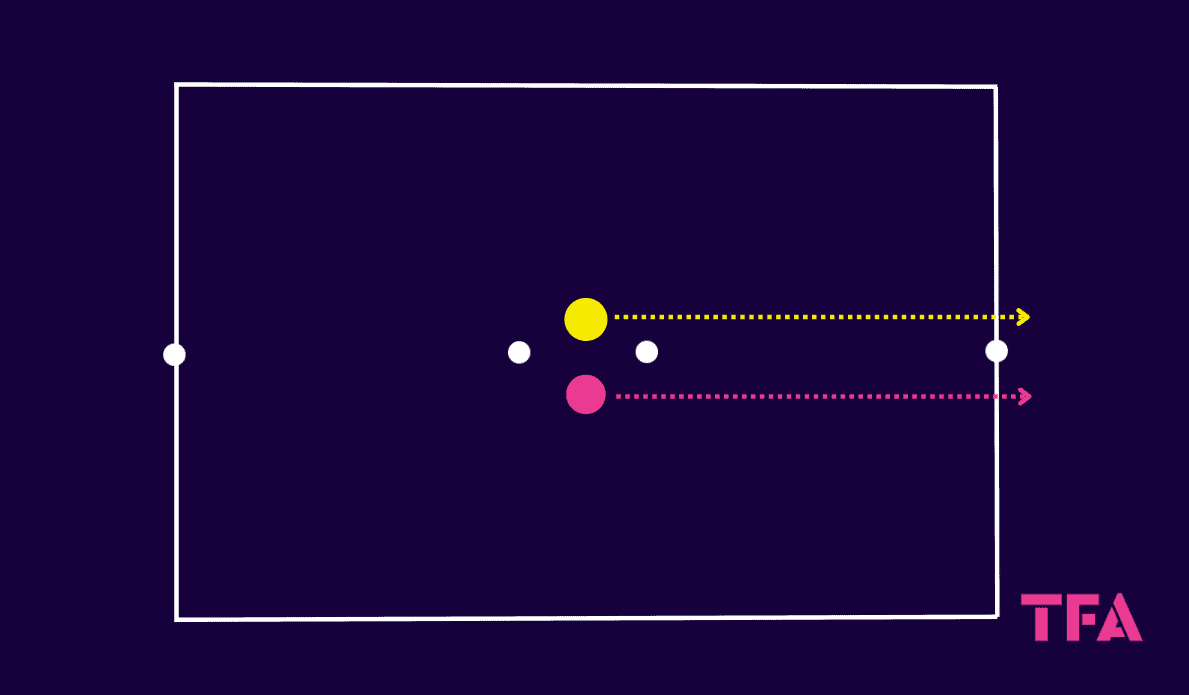

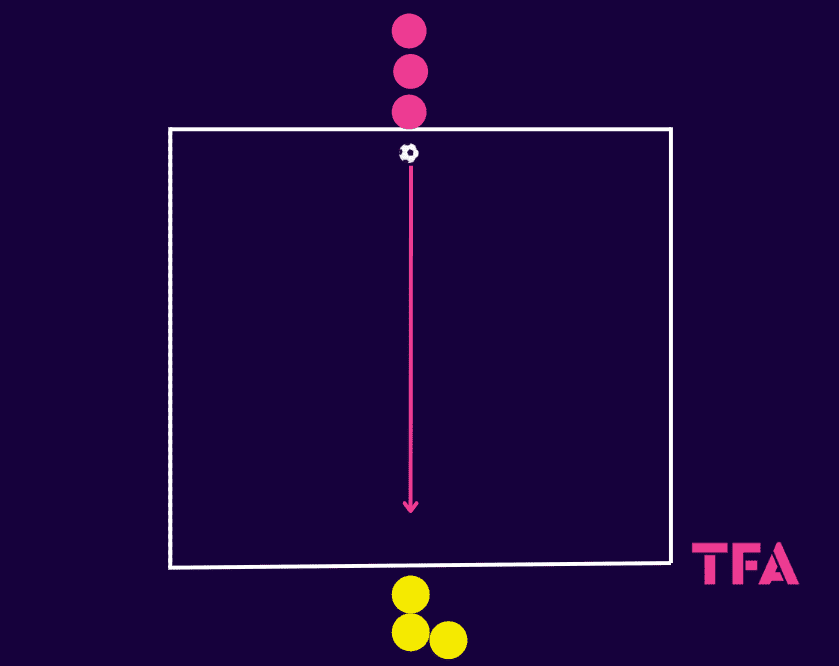

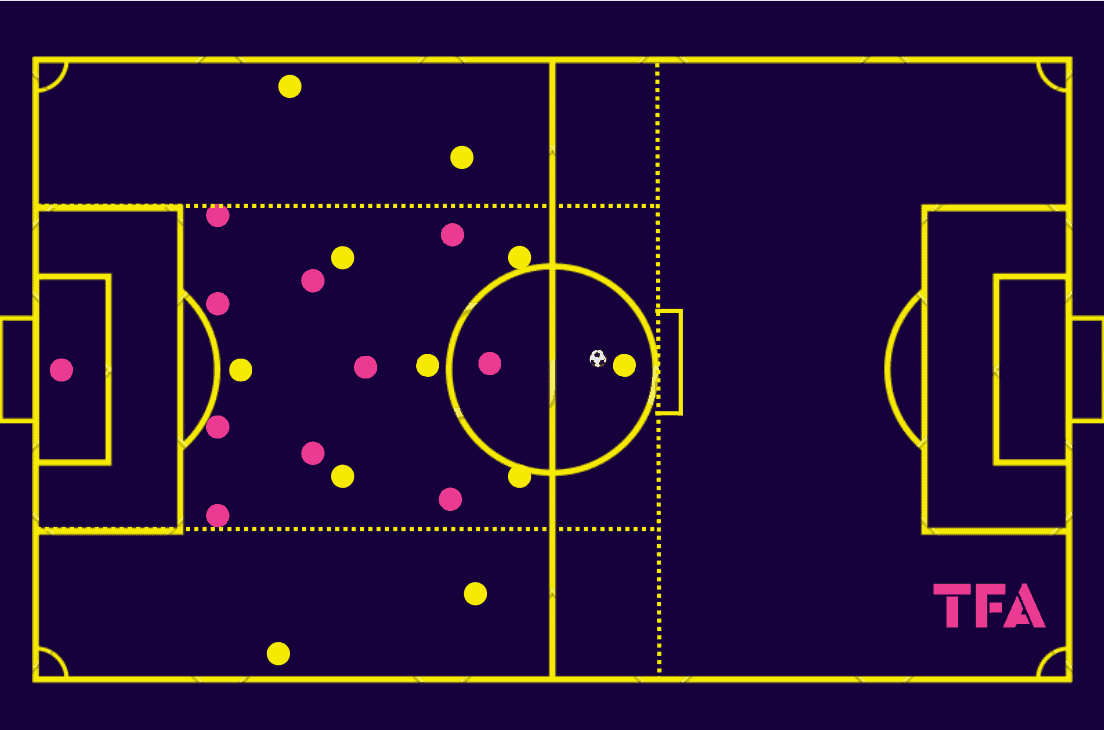

There’s nothing fancy with this next exercise. It’s a simple 1v1 ladder. The lines are three deep to incorporate recovery time but can extend to four as well. Multiple grids are ideal. Depending on the size of your team, you may even have three or four grids with promotion and relegation. The pinks represent the defending line, and the yellows represent the attackers. Pink will defend once, then switch sides to the yellow line. The pattern is to defend once attack once.

Players receive a point only if they dribble over the appropriate end line. The attacker must dribble over the defending side’s line, and the defending player must recover the ball and dribble over the attacker’s line. Each time a player dribbles over the appropriate end line, they receive one point. The players are to keep track of their points throughout the round, which is best at 3 minutes apiece. Once the round ends, the top three players receive promotion to the next grid and the bottom three players are relegated down the ladder. The three who win at the top grid stay, as do the three who lose at the bottom. Everyone else moves to a new grid.

Much like the last exercise, we want repetition without the repetition. The players will receive valuable opportunities to improve their 1v1 attacking and defending.

Even though our aim is to improve 1v1 attacking, the first break is an opportunity to review 1v1 defending technique. Talk about the objective of the defender as dictating where and when the opponent can go. Ensure the players aren’t defending straight on, taking a position just off-centre to discourage cutbacks.

If technical flaws are evident, talk about proper defensive stances. As seen in some of the early examples, defenders were caught with both feet facing the opponent. That is the traditional way of teaching a proper defensive stance. Rather than pointing both feet at the attacker, I teach players to point their front foot at the attacker while keeping the deeper foot at a perpendicular angle. That l-shape in the stance allows the defender to use a poke tackle if the defender cuts across or use the front foot to push off if the attacker knocks the ball past them and attempts to run.

You should be bent with the chest above the front knee. Arms are slightly out, prepared to make contact with the hands or forearms as the first point of contact when the attacker makes a move.

That’s your first break. For all subsequent breaks, hit the principles of 1v1 attacking, primarily focusing on reading the body mechanics of the defender and using deception and timing to bait the defender into a physical imbalance.

This converts to a circuit very easily, too. From 1v1, you can progress to 2v1, 2v2, 3v2 and 3v3. Once the players finish the 1v1 circuit, split each grid between shirts and pinnies. The players can now compete in highly competitive small-sided games relative to their positioning on the ladder. Count total points from the shirts and pinnies, adding the totals from each grid into one team score.

Setting up 1v1 duels

Now that we’ve established what the attackers should look for in their duels and how deception in tempo can create imbalances in the opposition’s body mechanics let’s go back to the very beginning, setting up 1v1 duels.

In the modern game, it’s common for high and wide wingers to carry the majority of the dribbling load. They’re typically the most dangerous in 1v1 situations, and their position on the field is least likely to handicap the team if the ball is lost. Plus, if the winger can win the duel, he forces the opposition to vacate valuable central positions, allowing teammates to run into those areas, often with limited tracking from the defensive team.

Those are big-picture approaches that relate to a team’s tactics. We will look at how to set up the duel, but not quite from that broad view.

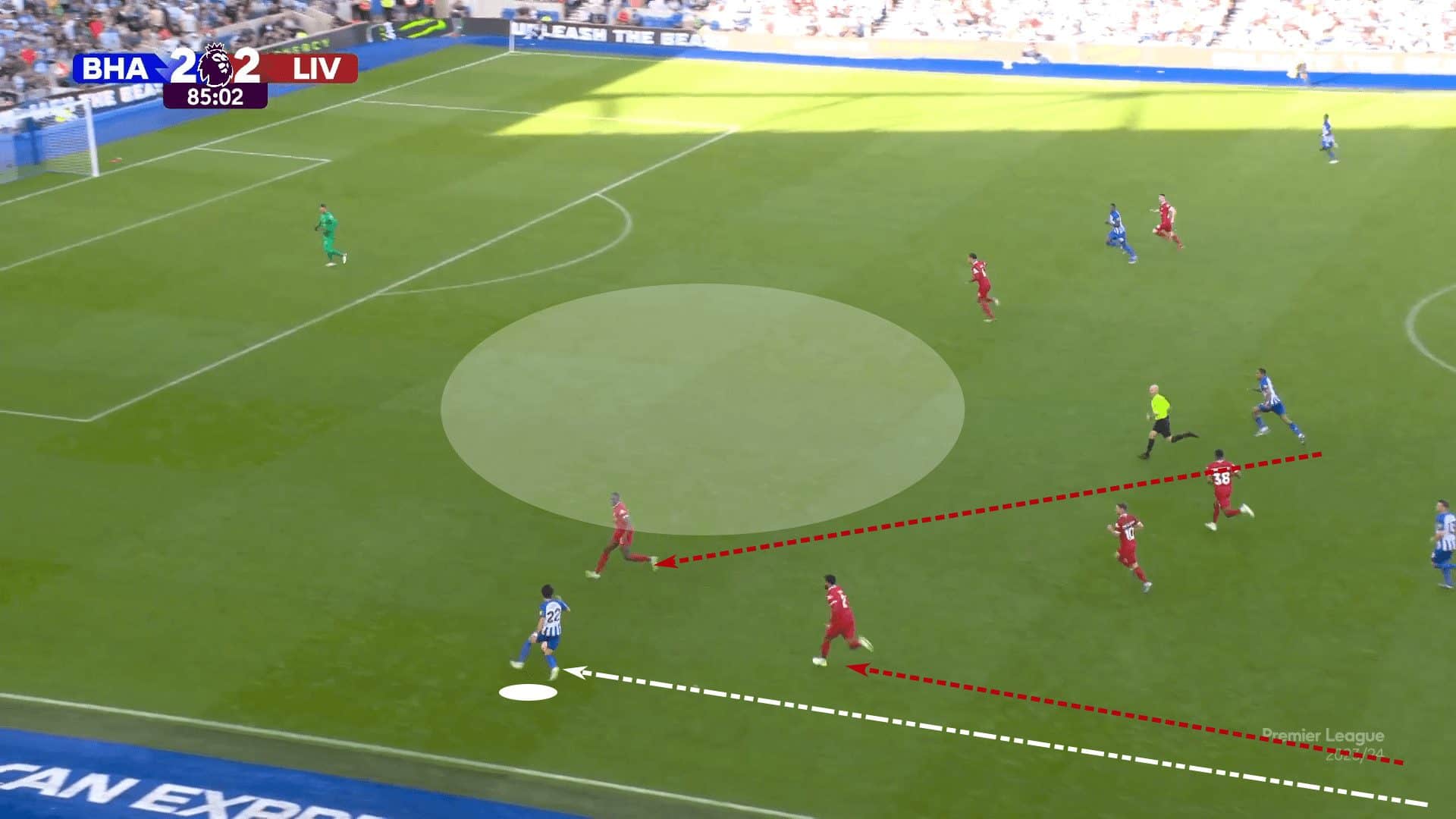

Let’s start with this example from Mitoma. Receiving the ball in a high and wide position, he took a few aggressive touches up the line, an unwelcome sight for any opposition. But Luton Town was quick to close down that space. They hustled to Mitoma in an attempt to pin him on the touchline. Mitoma’s first few touches were accelerations into space. That forced an equal-intensity response from Luton Town. As the defender closed the last 5 m, Mitoma quickly decelerated. Look at his balance as he awaits the oncoming defender. Mitoma is ready to quickly change direction.

He times his move to perfection, pulling the ball back and chopping it around the helpless defender. An attempt to hack Mitoma to the ground is the only way to end this play.

This is an example of using positioning to receive in space and quickly attacking that space to provoke a high-intensity run from the defender. Mitoma leveraged the defender’s momentum against him, using it as an opportunity to cut against his movement. Making the defender’s momentum work against him is a classic example of 1v1 attacking.

One of the more creative approaches noticed in the preparation for this tactical analysis was in the way both Mitoma and Kubo attacked 1v1 situations where the defender had cover. Common sense would tell the attacker to simply pass the ball away from a virtual 1v2. Just based on the numbers, a teammate should be open nearby, so why take on a low-percentage dribbling opportunity?

Mitoma’s approach is fascinating. In this example against West Ham, rather than taking the line and cornering himself against two players, he decides to cut inside and dribble at the cover defender.

By cutting inside, the two defenders switch roles, with the second defender now taking on first defender responsibilities. As the defenders switch roles, Mitoma finds a split second of confusion between the two. One has relinquished 1st defender responsibilities, and the other has yet to fully take them on.

The initial defender in the wing overruns his cover position, and Mitoma cuts behind him and bursts up the wing.

This is brilliant from Mitoma. What happens in this situation is that the deeper of the two defenders effectively screens the other from tracking Mitoma’s run. The Japanese international uses the first defender to set a pick and take uncontested space by attacking the second defender.

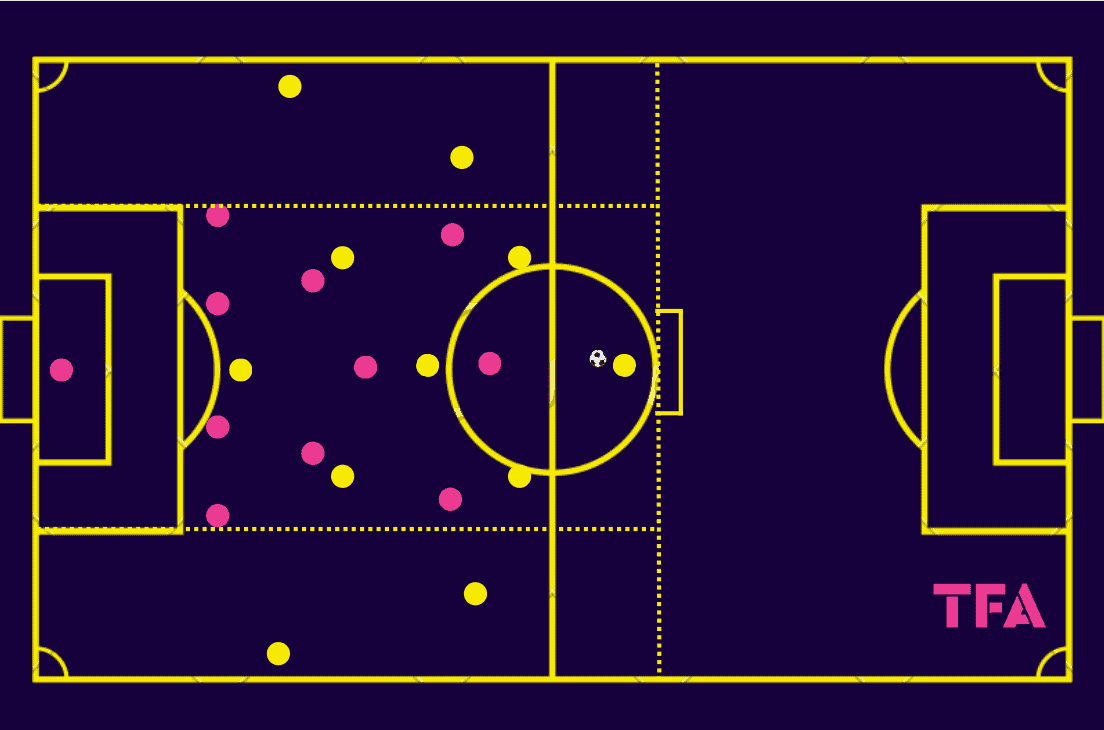

Back on the training ground, we want to help our wide players create better 1v1 attacking opportunities. To encourage 1v1s, we will section off the two wings and make a rule that the defending team can only have as many players in each wing as the attacking team does.

In this diagram, yellow has the ball and is playing out of the back. Initially, pink stays within the width of the box to deny central penetration. That opens up opportunities for yellow to attack through the wings. As yellow plays into the right wing, the wide forward and outside-back are in that channel, meaning pink can bring two players into that zone as well.

We want yellow to attack numeric equalities in the wings, especially if they can create 1v1s with limited cover behind the pressure defender. If cover does arrive, can the attacking team find a creative way to engage the opposition? Whether they are creating 2v2s as the outside-back pushes forward or the 1st attacker dribbles to the inside to attack the cover defender, we want the attacking team to gain valuable experience in these small-number battles.

We certainly want to help the wide players identify opportunities in the wings and discuss some attacking patterns they can create, but don’t neglect the central players either, especially the players who are running into the box. The players attacking the box must trust their wide teammates to do their job. If the wingers can create a better-than-average opportunity to beat the defender in get a service into the box, they should take it. If the odds are heavily stacked against them, help him see that this is not a time to take on risk with an ill-advised 1v1.

We want our wide players to attack numeric equality in small-number situations. However, there must be space to attack and a better-than-average chance they win the encounter. They have to earn their opportunities to dribble at the opponent. If they don’t use their positioning and movement off the ball to create those situations, then they don’t have the privilege of attacking from a position of weakness.

Help the players understand how to create optimal 1v1 attacking situations and to know when they’ve achieved that goal. Once they create these situations, trust them to do their job.

Conclusion

There you have it.

Three principles of 1v1 attacking with clear examples from some of the game’s best dribblers. Additionally, there are three exercises to train more effective 1v1 attackers.

The beauty of these exercises is that the rules are simple, making it easier to train the players on where to direct their focus. That’s really our objective here.

Rather than making a move and hoping it beats the defender, we want our players to understand that the move has certain objectives. We want to use deception and changes in tempo to create physical imbalances in the opposition or negatively impact his movement mechanics. 1v1s are a battle for balance. The attacker’s goal is not to make a move. Rather, it’s to put the defender in a position where he’s unable to respond to an accelerated move.

Little details but these are the points of emphasis to develop our 1v1 attackers and bring back the magicians.

Comments