Common features of positional play and the famous triangle offence, two of the most successful tactical systems

Phil Jackson and Pep Guardiola are rarely mentioned in the same breath. Yet, arguably, both have more in common with one another than with coaches from within their respective sports. Guardiola’s teams have largely been regarded as the gold standard for positional play in football, whilst Jackson is known for the famous triangle offence, but both place emphasis on the interconnectedness of the system (team) at all times whilst maximising the individual pieces within it. It must be noted that both strategies have evolved over time and have been adapted with regards to the league, personnel etc. Positional play has largely been viewed as an evolution of Johan Cruyff’s “Total Football”, whilst the man behind the triangle offence was Bulls and Lakers assistant coach Tex Winter.

Although they have operated in different sports, philosophically, they may not be so different. This piece will attempt to shed light on some of the principles both the triangle offence and positional play share, providing examples of how they are executed, and why they have been so successful.

Underpinnings of positional play and the triangle offence

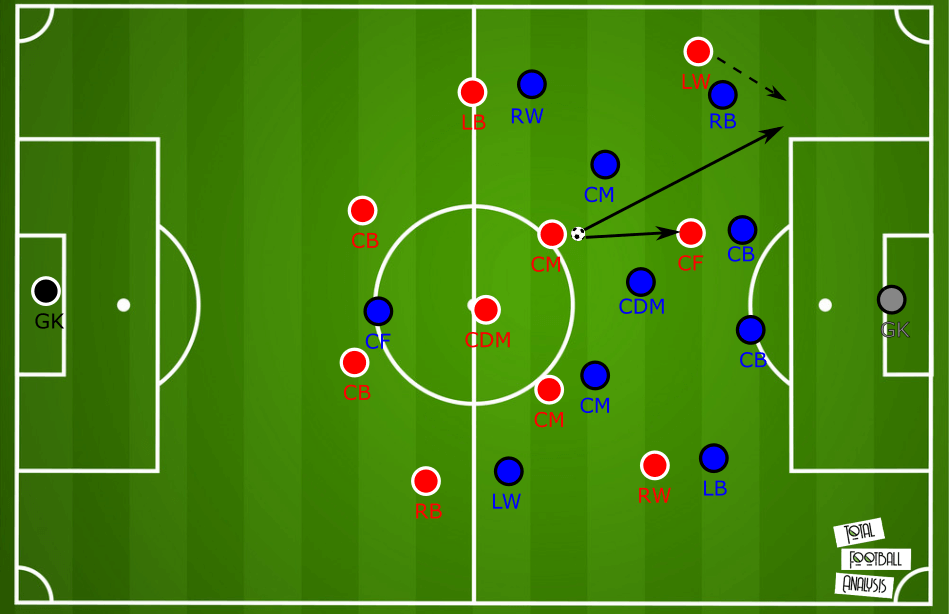

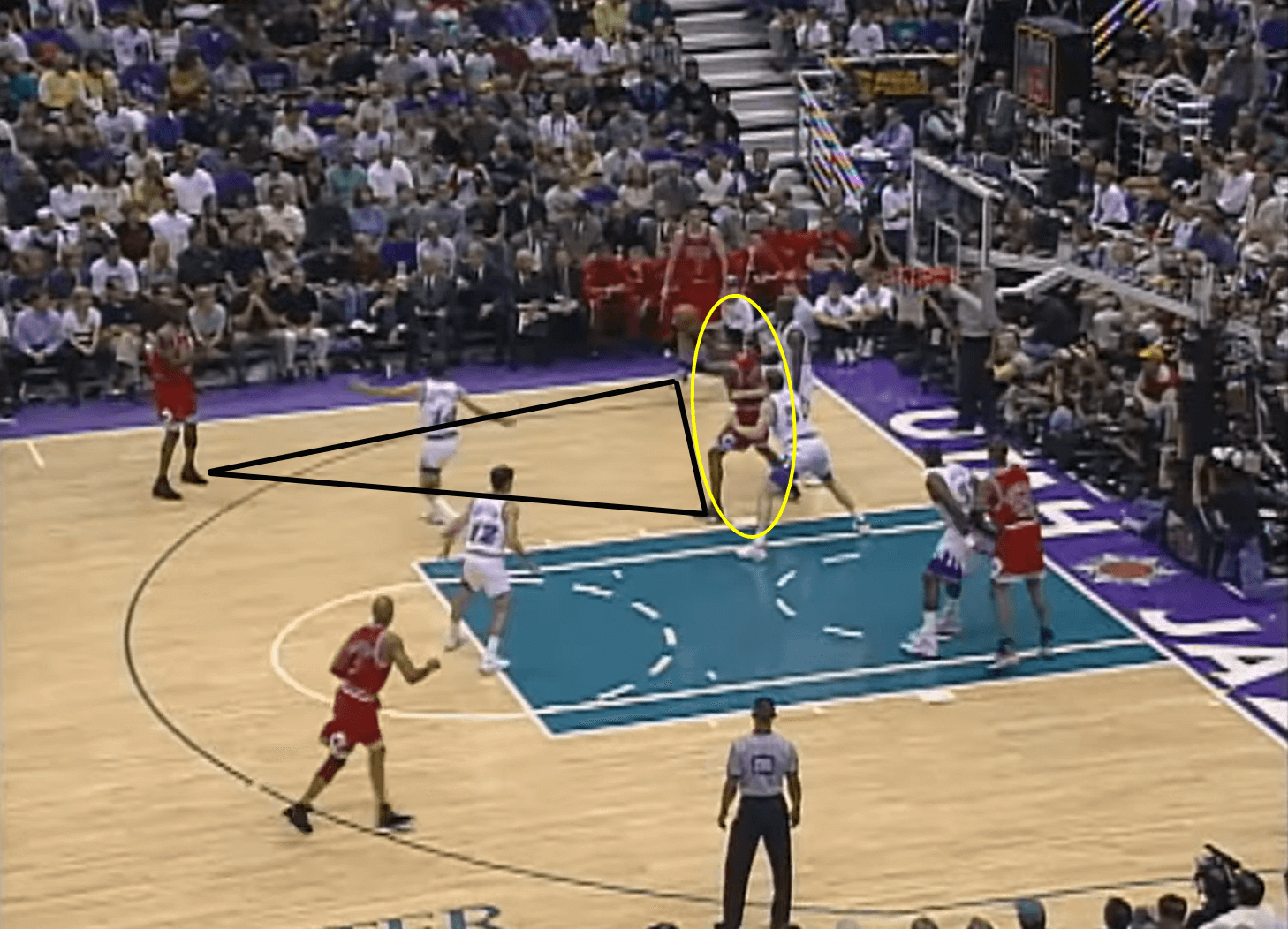

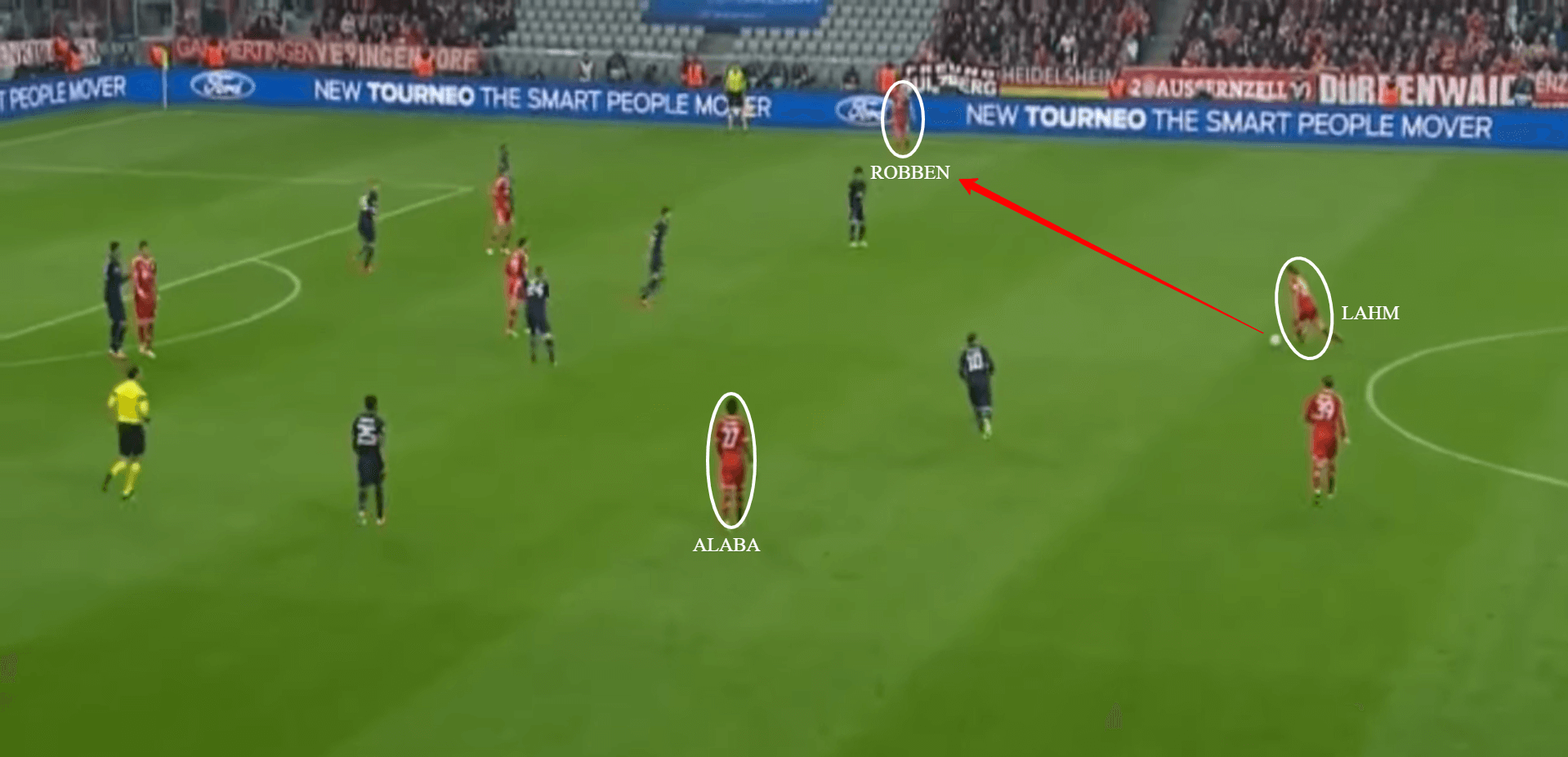

Positional play is underpinned by the search for superiority behind each line of pressure where possession is a consequence of purposeful actions. There is no pass completed for the sake of passing and as ex-Barcelona boss Guardiola has previously stated, the aim is to “move the opponent, not the ball.” Positional play requires players to occupy certain spaces on the pitch depending on the location of the ball, as opposed to a specific formation. Zonal positioning in possession is commonly staggered creating triangles, diamonds and closer passing options which lead to safer decisions. The players who do this can be interchangeable, and through efficient ball and player movement opposition lines can be penetrated. The image below, although fairly extreme, with three players behind the opponents’ midfield line in a small area, does highlight how positional play can manipulate the opposition’s defensive structure as we see six opponents who have been drawn into a small area who are likely to be extremely vulnerable if the play is switched.

The triangle is commonly known as a ‘read and react’ offence which lends itself well to dynamic and unpredictable sports such as basketball. The offence runs as a sequence of options, with each new pass triggering a new set of options. There are no set plays with predetermined decisions or actions within the triangle offence. Rather, each offensive sequence is built for the player who is open to score, not a specific individual who can be nullified by the defence. The offence can be run continuously until an open scoring opportunity presents itself, unlike set-plays with a predetermined finish point. There are multiple ways for a team to create the triangle and once it is initiated, the players will be tasked with making the most favourable offensive read at that moment, based on the series of options afforded to them by the way in which the defence plays. All five positions are interchangeable and players are always involved in the offence irrespective of whether they are in possession of the basketball or not.

Searching for superiority

Tactical analysis often describes superiority in positional play as positional, qualitative or numerical. It must be noted that these three types of superiority do not exist in isolation, and can be intertwined within a specific situation. This can be in favour of a team both in and out possession. The principle of positional superiority is a major similarity between positional play and the triangle system.

Positional superiority is contextual, based on a team’s intentions and tactics in a given situation in a match, but, generally, it refers to players taking up advantageous positions in relation to their opponents in order to achieve a certain objective, i.e. play through lines of pressure. Players are often positioned on different horizontal and vertical lines, creating triangles and diamonds which afford passing options in between lines. Often, numerical superiority is coupled with positional superiority to truly be effective.

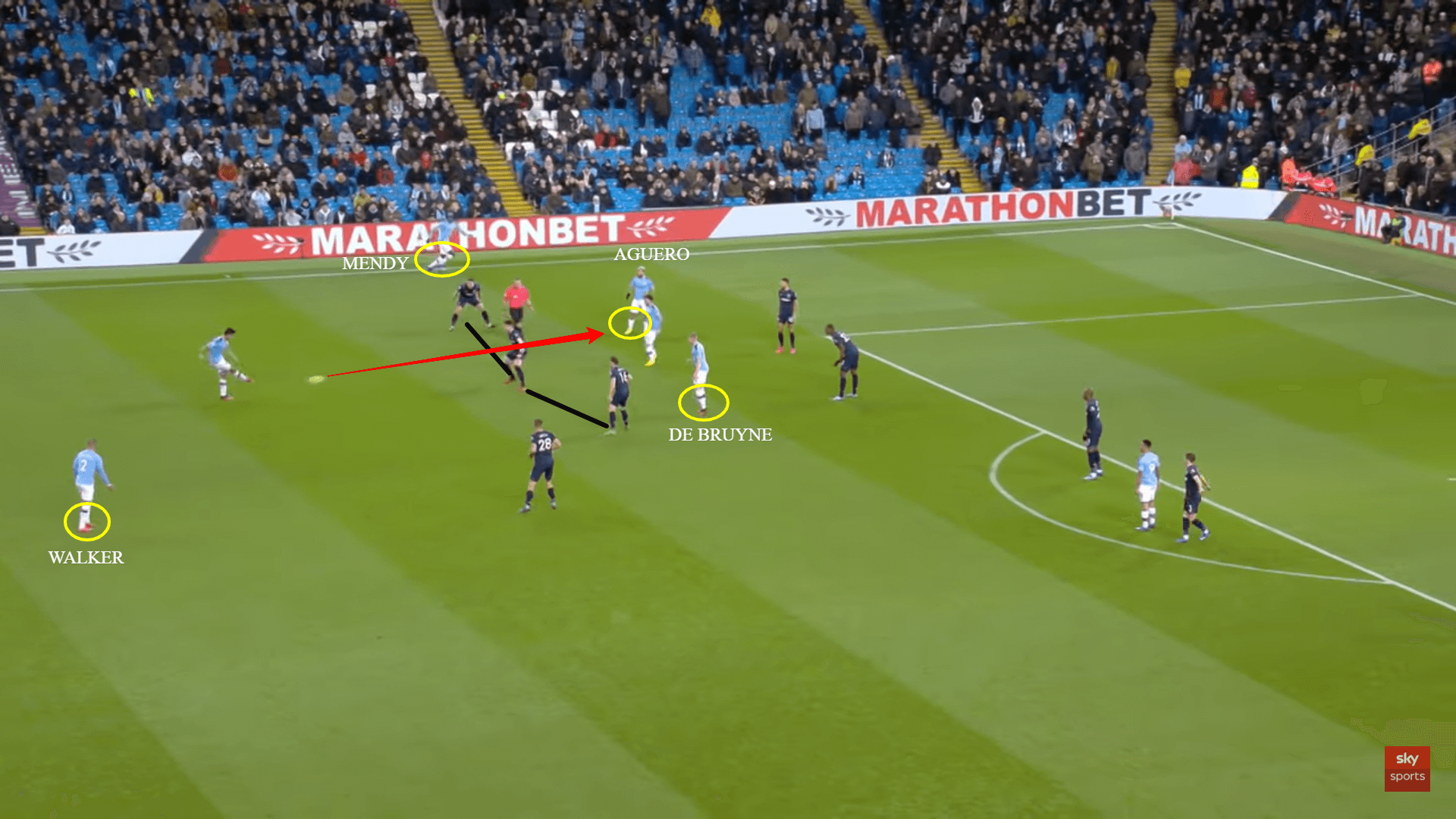

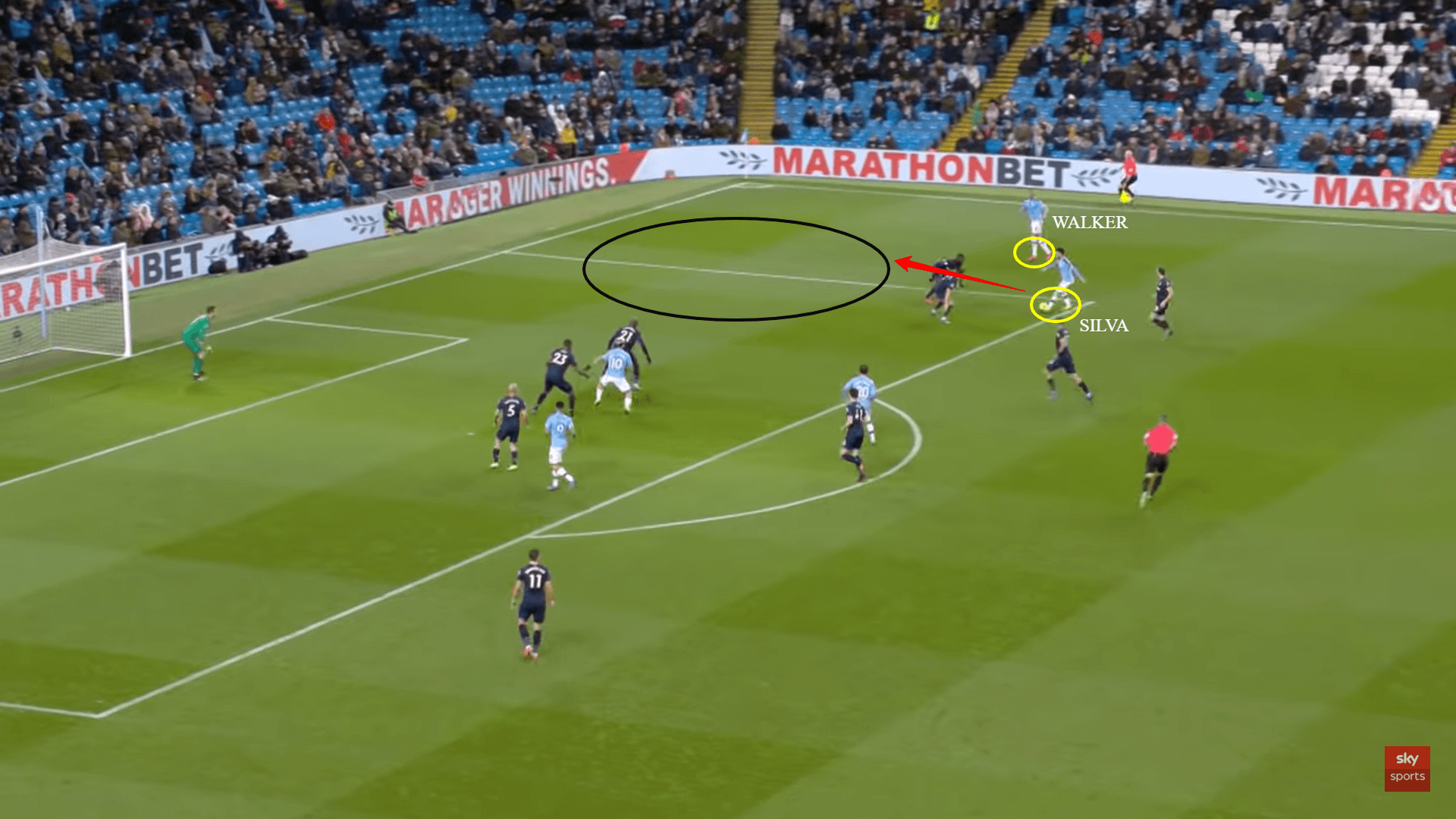

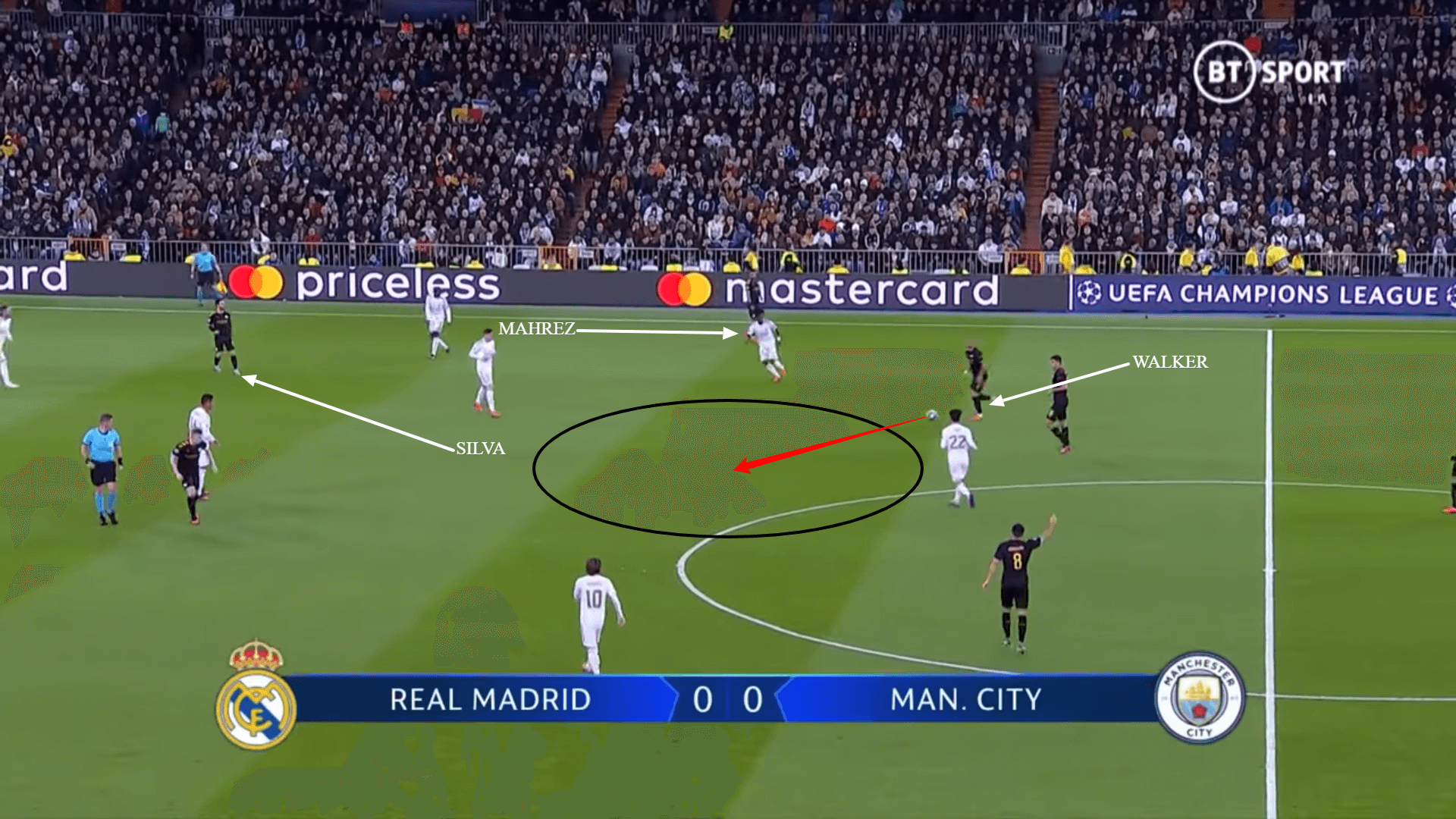

Positional superiority is used to break opposition lines of pressure and penetrate the defence to create scoring opportunities. The players’ staggered positioning across zones often results in interior spaces and passing lanes within the opposition’s formation “in between the lines” opening up and assisting player’s attempts to find the free man. The image above is a prime example of this by Man.City as Kyle Walker finds Bernado Silva in between the lines. The ball is used to eliminate opponents through penetrative vertical and diagonal passes forward to generate superiority behind the line of pressure. Vertical passes predominantly eliminate one line of pressure whereas diagonal passes can often beat two lines of pressure as evident in the diagram below.

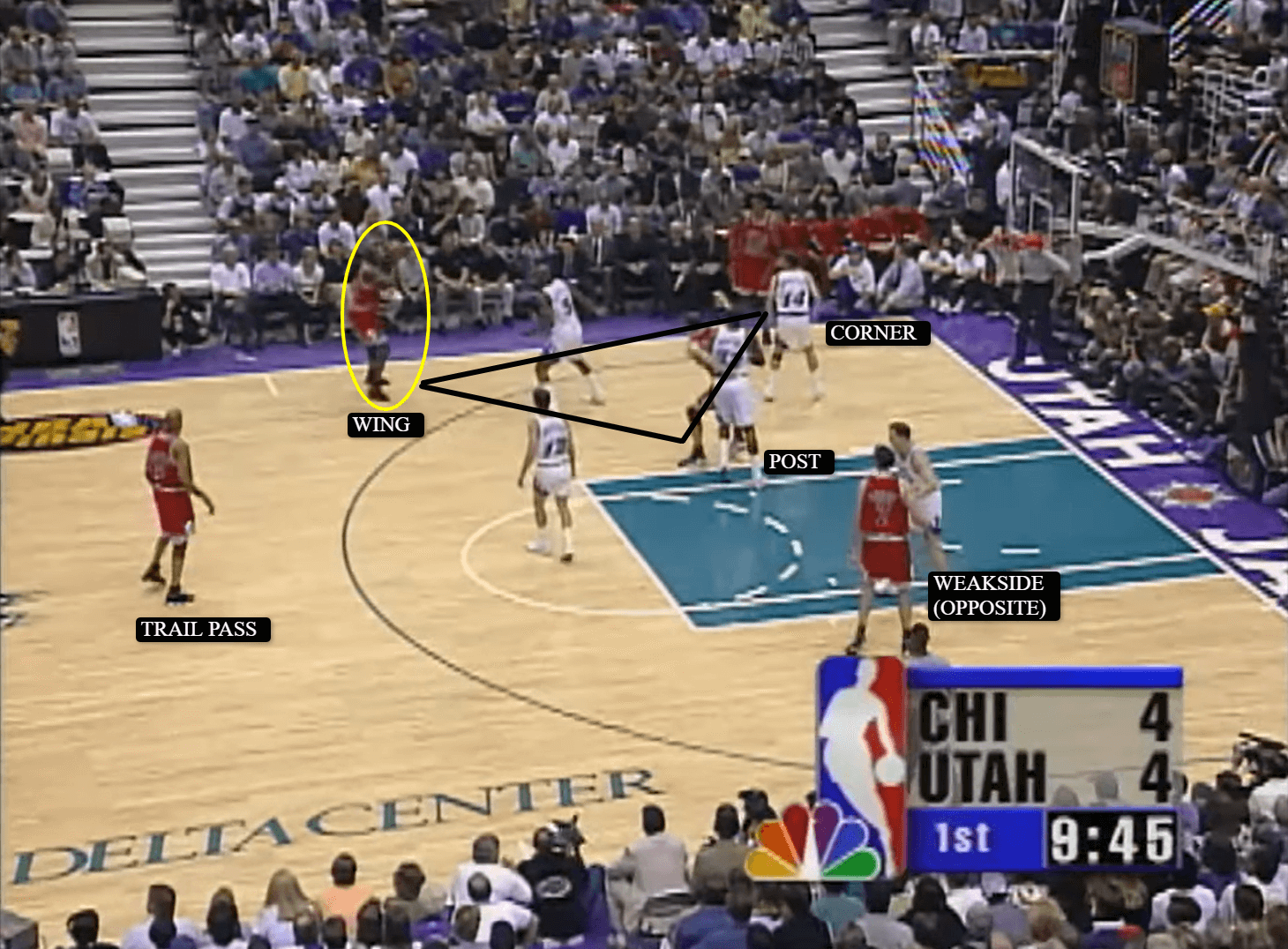

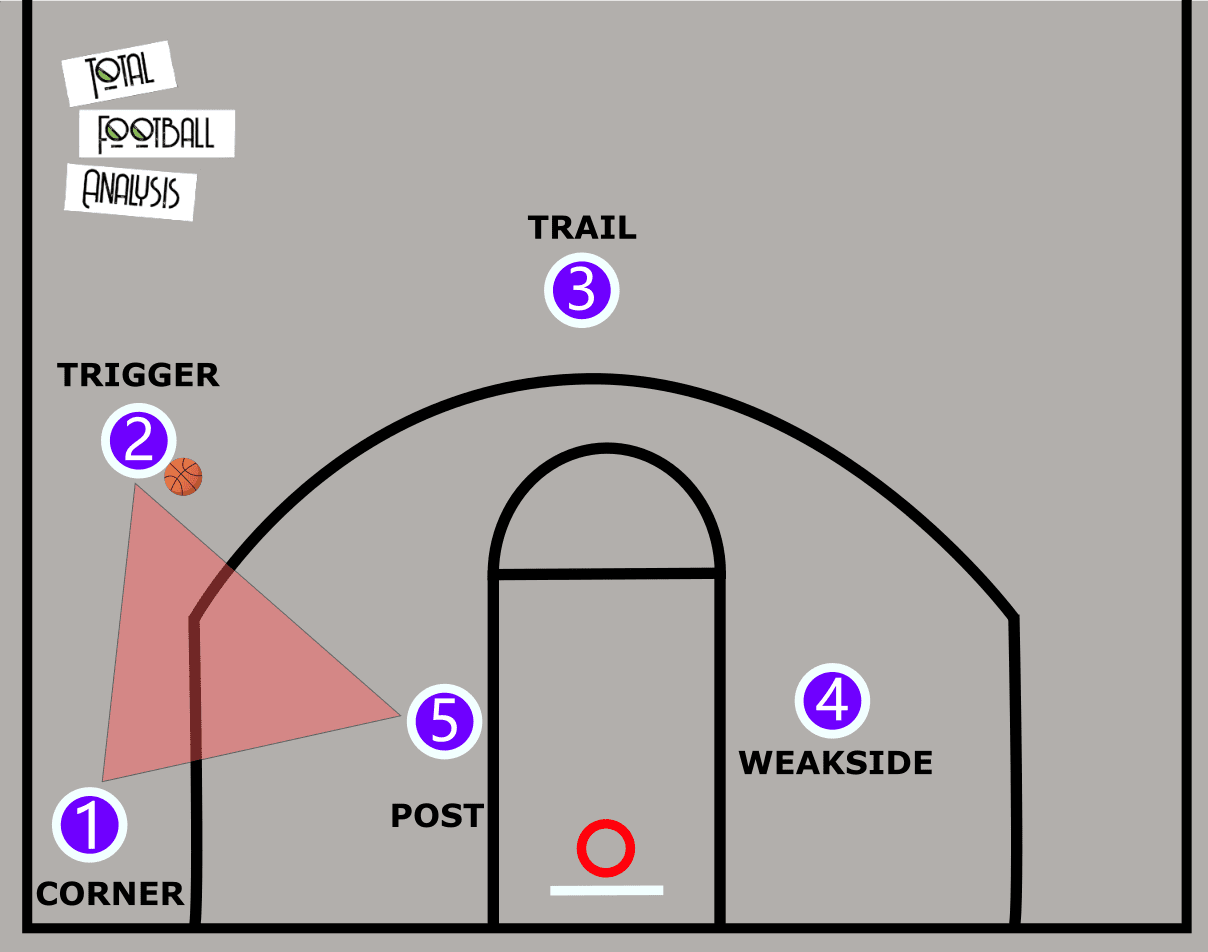

Similarly, penetration is a key aspect within the triangle offence as players attempt to break through the frontline defence. Initially, this is done during the creation of the commonly known side-line triangle. From that point, the player located in the post area behind the defence and closest to the basket is frequently targeted. It’s from here that a sequence of options can then develop. This player can often act as a traditional #9 would in football, receiving the ball, triggering various actions such as midfielder’s movement to support in front of them, as well as attacking movements beyond them and in behind the opposition’s backline. Below the triangle is initiated by Jordan who plays to the corner. The Bulls penetrate from the corner, playing inside to Scottie Pippen who is positioned behind the initial line of pressure in the post and is able to get a scoring opportunity.

The premise of qualitative superiority is that a 1vs1 or 2vs2 situation (or other) may not be equal. Few will argue with the notion that in a 1vs1 situation against Michael Jordan, there is anything remotely equal. To identify this, one must understand the opposition’s individual and collective weaknesses. Matching a team’s best players with the opposition’s weaker players could lead to advantageous outcomes. Below we see that although Silva and Walker are in a 2vs2 situation, Walker is extremely fast. The pass down the flank that Silva eventually plays is extremely effective in getting behind the opposition’s backline as they cannot match Walker’s speed.

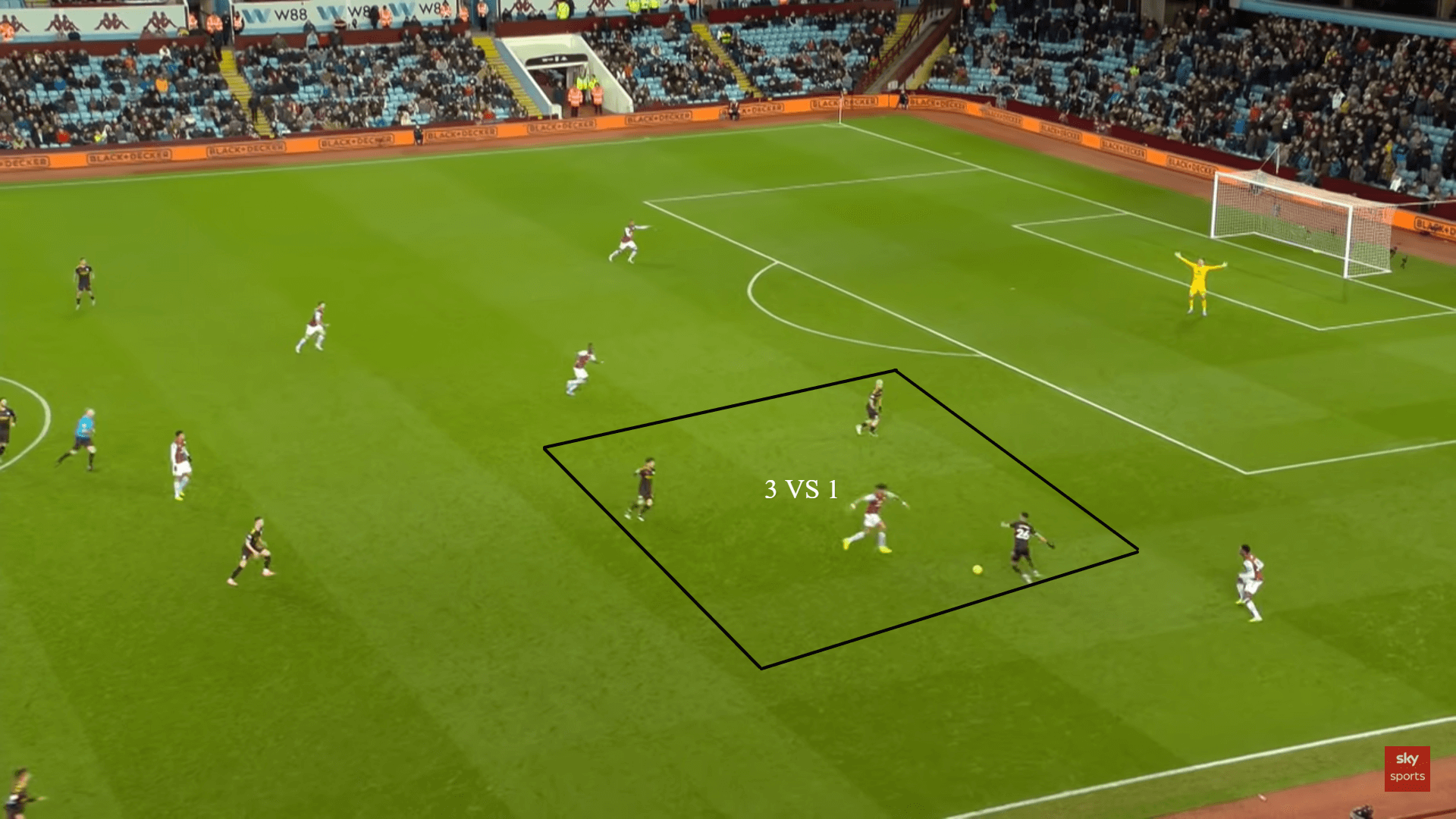

Numerical superiority occurs when one team has outnumbered another in a given zone and can also be known as an overload. Creating overloads is one way a team in possession can break the opposition’s lines and advance the ball forwards. An example of this in possession could be the use of the goalkeeper as a free player when attempting to build the attack from the defensive third. His role is to help facilitate ball circulation until a penetrative pass can be played to break the opposition’s press.

In basketball, numerical superiority can occur, during fast breaks in attacking transition. However, the triangle is commonly initiated in a half-court situation where there is numerical equality, 5 vs 5, with each player guarded. Here, the triangle can be influential in creating qualitative superiority in the form of mismatches and switches between players, and positional superiority with the high usage of the ‘screen’ action that is performed in order to put players in advantageous positions when creating and finishing the attack. We will now look at some key principles that positional play and the triangle offence share and unpick why they are often so successful.

Spacing and positional structure

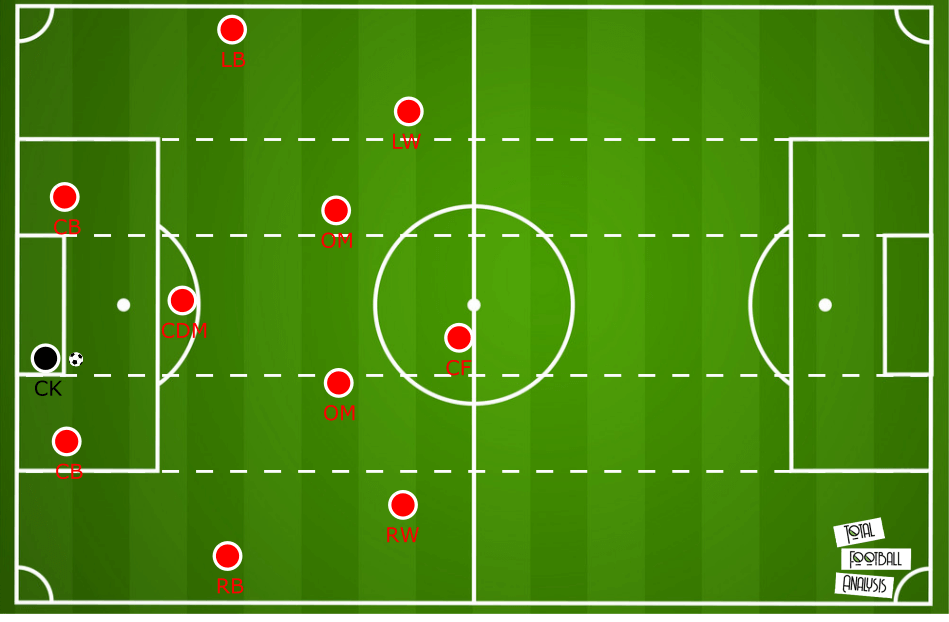

Within Guardiola’s positional play, positional structure is dictated by the intention to create triangles and diamonds in possession. To guide this global behaviour of a team, a principle that is often followed is that in relation to the ball, at any one time, a maximum of three players can occupy a horizontal line across the pitch and a maximum of two players can occupy a vertical line. In a 4-3-3 system, this implicitly affords these structures to be formed more easily, maintaining fluidity and structure in players’ movements whilst affording freedom of action which will be decided with regards to the context within the situation in the game, i.e. ball location, teammates and opposition position, and the space available. Below is an example of a common staggered positional structure a team may adopt when playing out from a goal kick following the aforementioned principle.

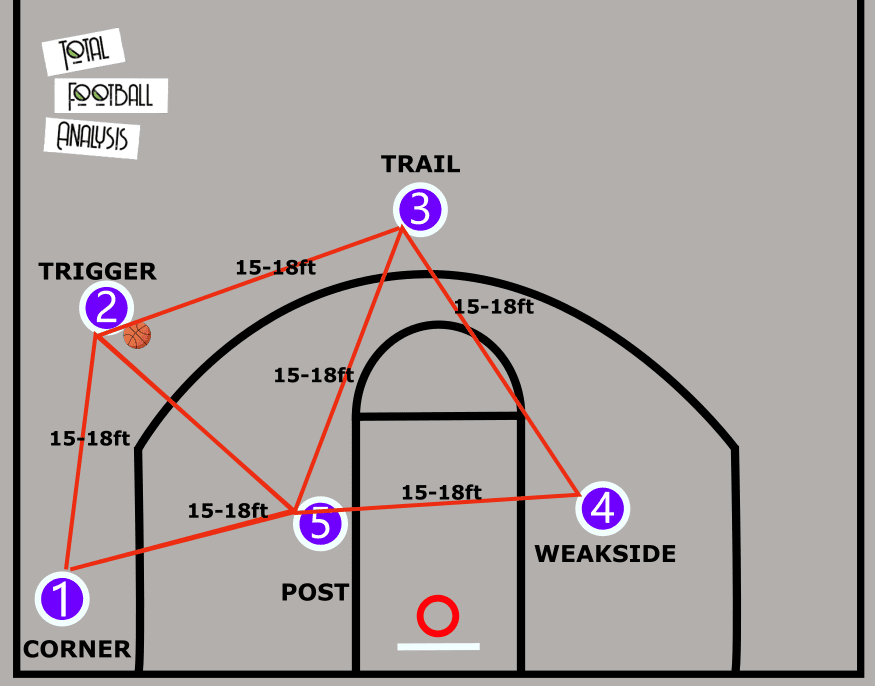

A key principle of the triangle offence is spacing which provides the platform for forthcoming actions. Players are required to take up positions between 15 and 18 feet apart, which opens up passing lanes for the player on the ball and space for movement off the ball. As stated previously, within the triangle structure, players are responsible for choosing one of a sequence of options which become available depending on where the ball is and what the defence is doing. This is by no means restrictive. As Phil Jackson stated, the triangle in some ways can be similar to a Jazz piece where you can, “take off on the various themes and run your own little music run, as long as you still know what the melody is.” In this case, the melody is the principle of spacing and the individual music run is the individual’s decision making within this structure.

Additionally, if the defending team decides to provide help to the primary defender and “double team” the ball handler, the defender who comes across to provide help will subsequently leave their player open. By maintaining distances of 15-18 feet between themselves, the defender will have a large distance to cover before they can get back to the player they were marking. It is down to the offence to recognise where the numerical superiority is in this case and exploit this by finding the free man for an open shot.

Using movement off the ball to create

Fundamental to both the triangle and positional play is movement off the ball. With regards to football, every player is expected to contribute to building and creating the attack, similar to the triangle in basketball where everyone is involved in the offence. All players’ positioning and movement has a direct or indirect consequence to a specific scenario, versatility is key as positions are interchangeable.

What is common here is that, in both positional play and the triangle offence, the favourable triangle structures created are largely predicated on width, penetration and cover/balance. Cover and balance allow for a team to maintain defensive balance when in possession of the ball in addition to providing an option to change the point of attack. Greater width allows for potential passing options to open up centrally as it often spreads the opposition affording vertical passes. It also creates a safer passing option to a player with more time and space to make a decision. Finally, penetration often allows for the team in possession to force the opposition backline to retreat, giving more space to play in front.

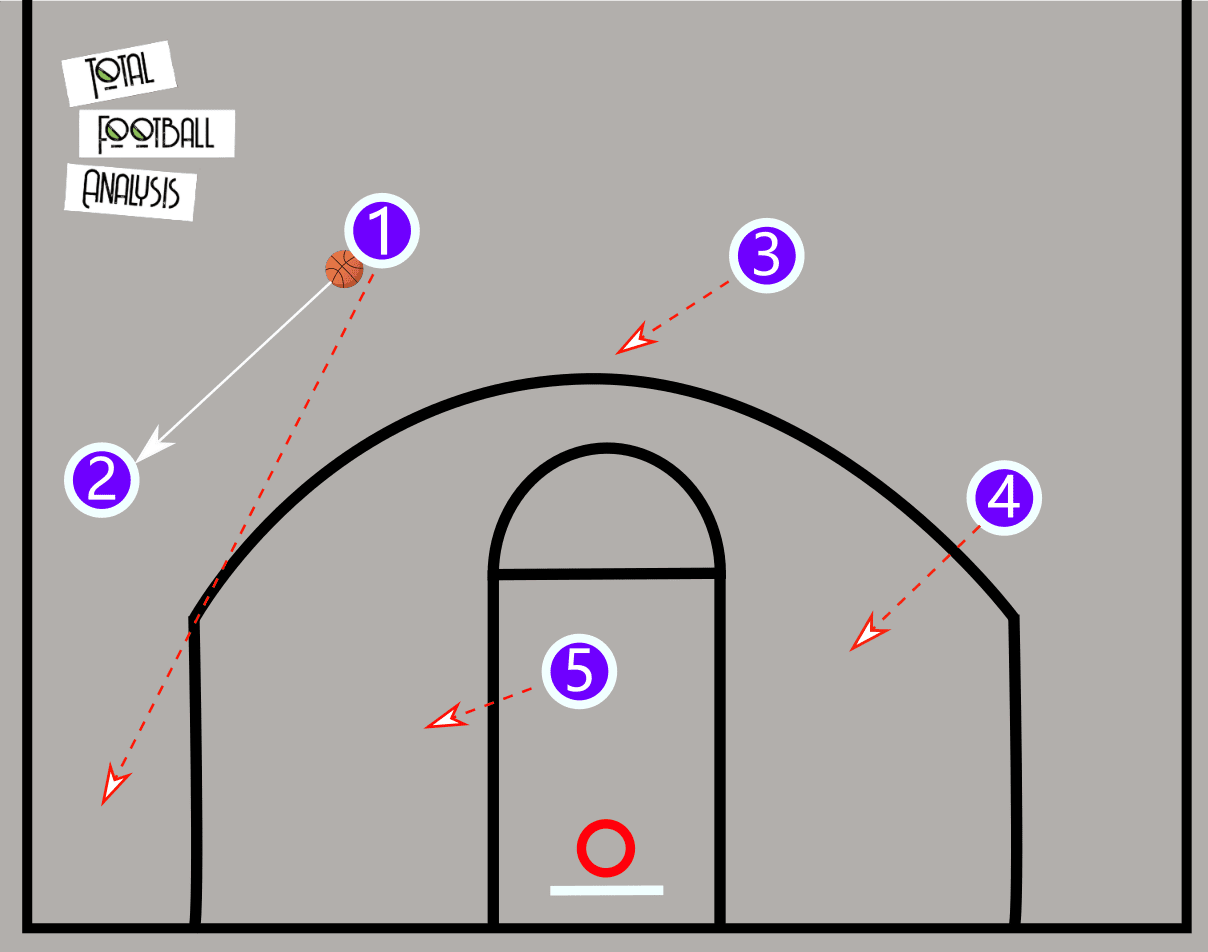

The triangle involves a three-player ball side triangle, comprising of players in the corner, the wing, the post, and two players on the weak side, one providing width and one as the trail pass option. Off ball movements are coordinated based on what is known as the “moment of truth.” The line of truth is a horizontal line about three feet in front of where the frontline defence is positioned (highest defender). The moment of truth is the point at which the ball handler arrives at the line of truth and ideally releases the ball. The offence is initiated once the ball is passed to the wing position, also known as the one-pass, (to create the triangle). Everyone has a responsibility to react at this point. Stay with me. Once the triangle is created on the ball side, players must make the number two-pass (what you do once you have created the triangle), with each two-pass triggering a sequence of further options. Often players will play the two-pass into the player in the postposition however this is not always the case as players are asked to follow the “path of least resistance” and take what the defence is giving them.

The image above is commonly how the triangle is formed. #1 plays the one-pass to #2 before cutting down to the corner. #5 comes across to the strong side post in order to form the triangle. #3 will position themselves at the top of the key whilst #4 will stay on the weakside providing width.

In positional play, the concept of the “free man” can be used to devastating effect if implemented effectively. Often, if a centre-back has the ball, the other centre-back is often free as there are normally more defenders than attackers resulting in numerical superiority. As a result, if the centre-back progresses the ball in order to draw out an opponent, a central midfielder may become the “free man” in a position of positional superiority as they are positioned behind the first line of pressure. Often this results in a team advancing up the pitch.

In football, a key element which has gained an increasing amount of attention is that of rotations. Pre-occupied space can lead to static positioning resulting in players that are much easier to mark. A player that is arriving into space is much harder to handle than a player waiting in a space, thus, like the triangle, coordination of movements are key. The type of rotation can vary depending on the area of the pitch the ball is in however they can be used to create space, generate superiority, and create progressive passing options and shooting opportunities.

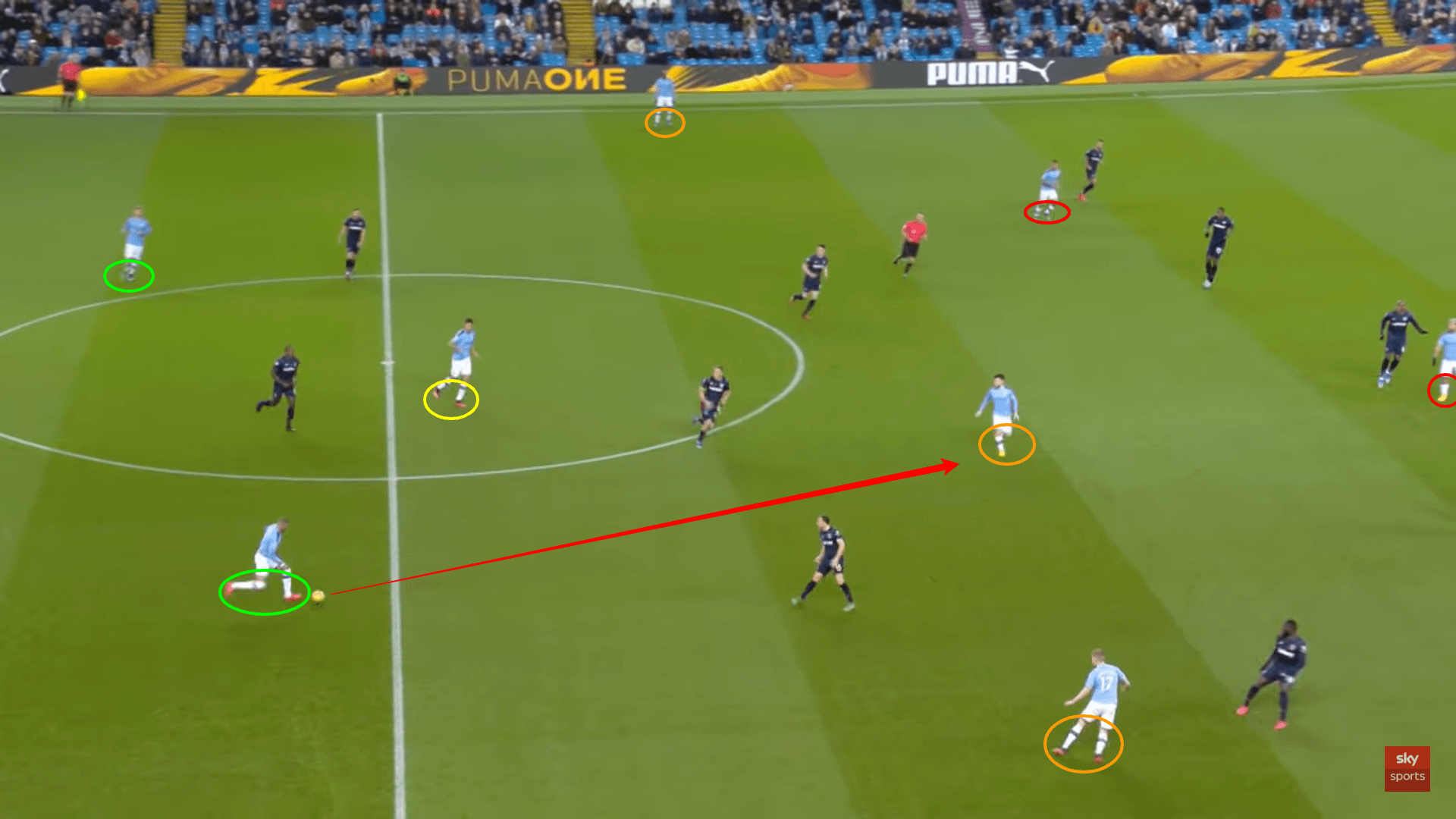

Below is an outcome of a rotation executed by Man.City in a wide area to create space centrally. As the ball is played into Riyad Mahrez, he takes a touch away from pressure dropping down the touchline. Silva leaves his central area instantly to make a forward run which allows Walker to drive inside after receiving a pass from Mahrez.

Catering for the individual within the teams’ structure – qualitative superiority

Understanding what the strengths of your team are and creating the right structure to emphasise these strengths is critical and both the triangle and positional play allow for this. As previously mentioned, this can be done in the form of qualitative superiority. For example, during his time at Bayern Munich, Guardiola utilised the fact that he had two world-class wingers at the time in Frank Ribery and Arjen Robben and employed inverted full-backs in David Alaba and Phillip Lahm, who played in central positions, creating overloads in midfield. More importantly, this meant that their respective wingers would have to follow them inside, affording Bayern opportunities to play directly into Ribery and Robben who would have their full-back in an isolated 1vs1 situation. As we saw so often, Bayern reaped the rewards of this qualitative advantage with both wingers wreaking havoc, most notably from Robben. The Dutchman scored many goals which originated from a 1vs1 in a wide area before coming inside on his favoured left foot to shoot and score.

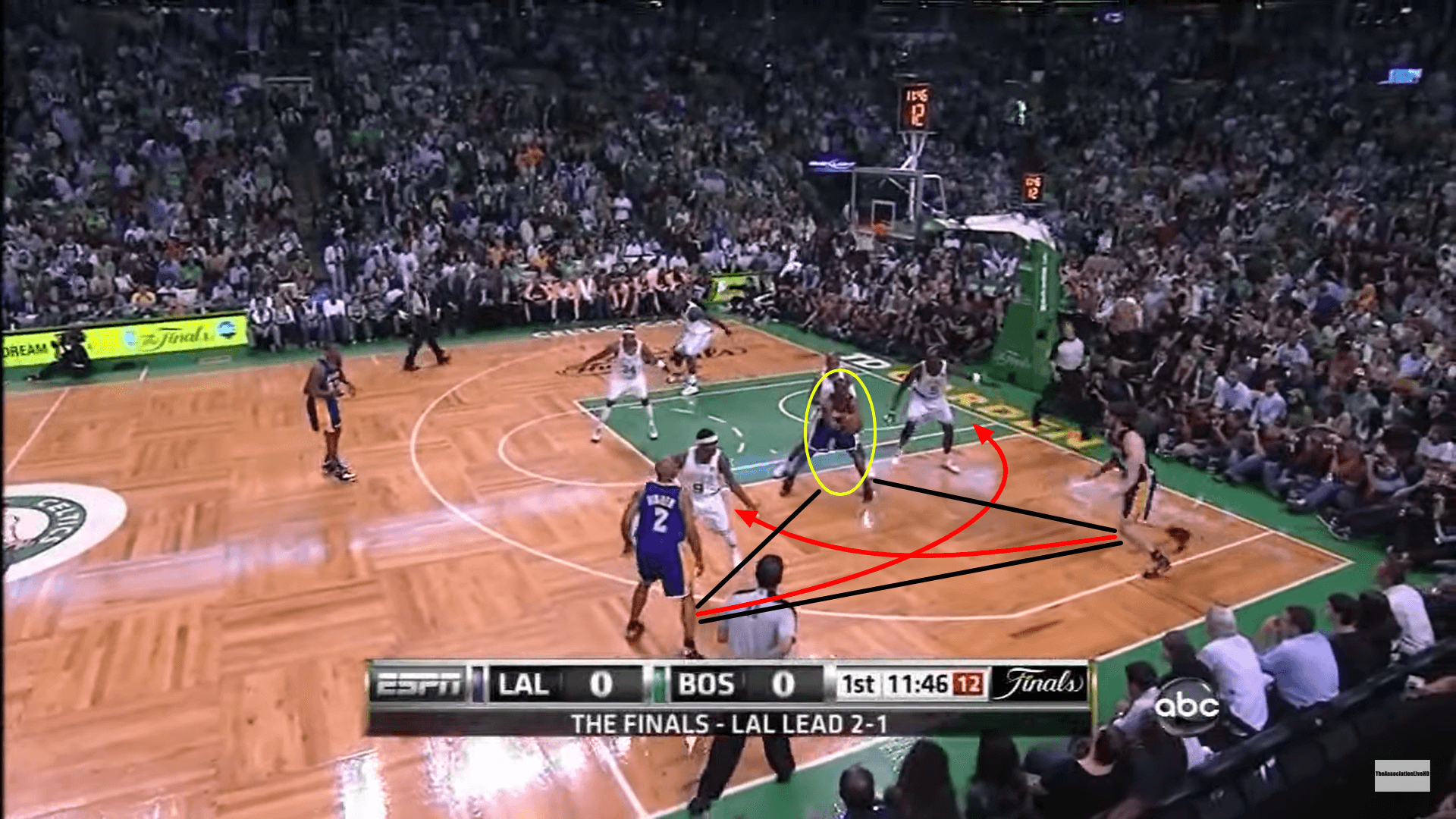

When using analysis to unpick the triangle, although there is no predetermined play as such, there are options which may be more favourable, especially when players of the calibre of Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant are at hand. As was seen so often, options that were created put Jordan and Bryant into 1vs1 situations, which would then allow them to assert their dominance on the game within the triangle offence, thus catering for the individuals within its system. This could occur if they positioned themselves on the weak side. Once the ball was swung from the wing to the trail pass option, “two-man game” (2vs2) was initiated where isolation situations could be created or, straight out of the triangle as pictured below. Bryant is in the post, Paul Gasol and Derrick Fisher, who make up the corner and the wing position respectively, make runs around Bryant, taking their defenders away and leaving Kobe in a 1vs1 situation of qualitative superiority.

Aggressive counterpress and offensive rebounding

Although the concepts that have been mentioned predominantly address in possession actions, it must be noted that both positional play and the triangle offence can have an impact during defensive transition. A significant trait of a team who adopts positional play principles is that, as soon as the ball is lost, an aggressive counterpress is initiated to win the ball back quickly. Due to the short distances between players who previously supported their teammate in possession of the ball, they now have short distances to cover in order to win the ball back and often gain numerical superiority in the zone in which the ball is lost as a result.

Whilst the spaces that must be covered on a basketball court are much smaller than a football pitch, fast-break opportunities are a consistent threat and quick defensive transitions much like in football, can be critical to stopping counterattacks. With that in mind, shots taken as a result of the triangle offence provide strong rebounding opportunities due to player positioning. Additionally, in the triangle offence, there is always one player who is known as the “lag pass” or trail pass option positioned around the top of the key. This player provides support in possession and is critical in providing defensive balance, preventing transition opportunities and fast-breaks from the opposition.

Conclusion

It is safe to say both Guardiola and Jackson have made a significant mark on the way their respective sports are played and analysed. Although coaches from different sports, in this piece I have hoped to unpick some of the similarities between the principles of positional play and the triangle offence, highlighting why these systems have been so successful.

Comments