Tim Walter caught global attention last year during his time in charge of 2. Bundesliga side Holstein Kiel, where he secured a sixth placed finish. His side caught such attention due to the inventive and somewhat radical build up Kiel used, and Walter has such been hailed an innovator for some of his strategies. These innovations have continued into the new season, where Walter now manages recently relegated side VfB Stuttgart, who sit third in the table currently.

Walter’s playing philosophy is built around possession of the ball, and how the movement off it can move the opposition and ultimately create goal-scoring chances for his side. As a result, his sides tend to be very well coached in possession, meaning teams against Walter almost always set up in a compact deep block, seeking to reduce the effects of Walter’s side’s positional play. This tactical analysis will examine this positional play and the tactics of Tim Walter and his Stuttgart side, and show why he is one of the most promising managers coming through the ranks in Germany.

Breaking the first and second lines of pressure

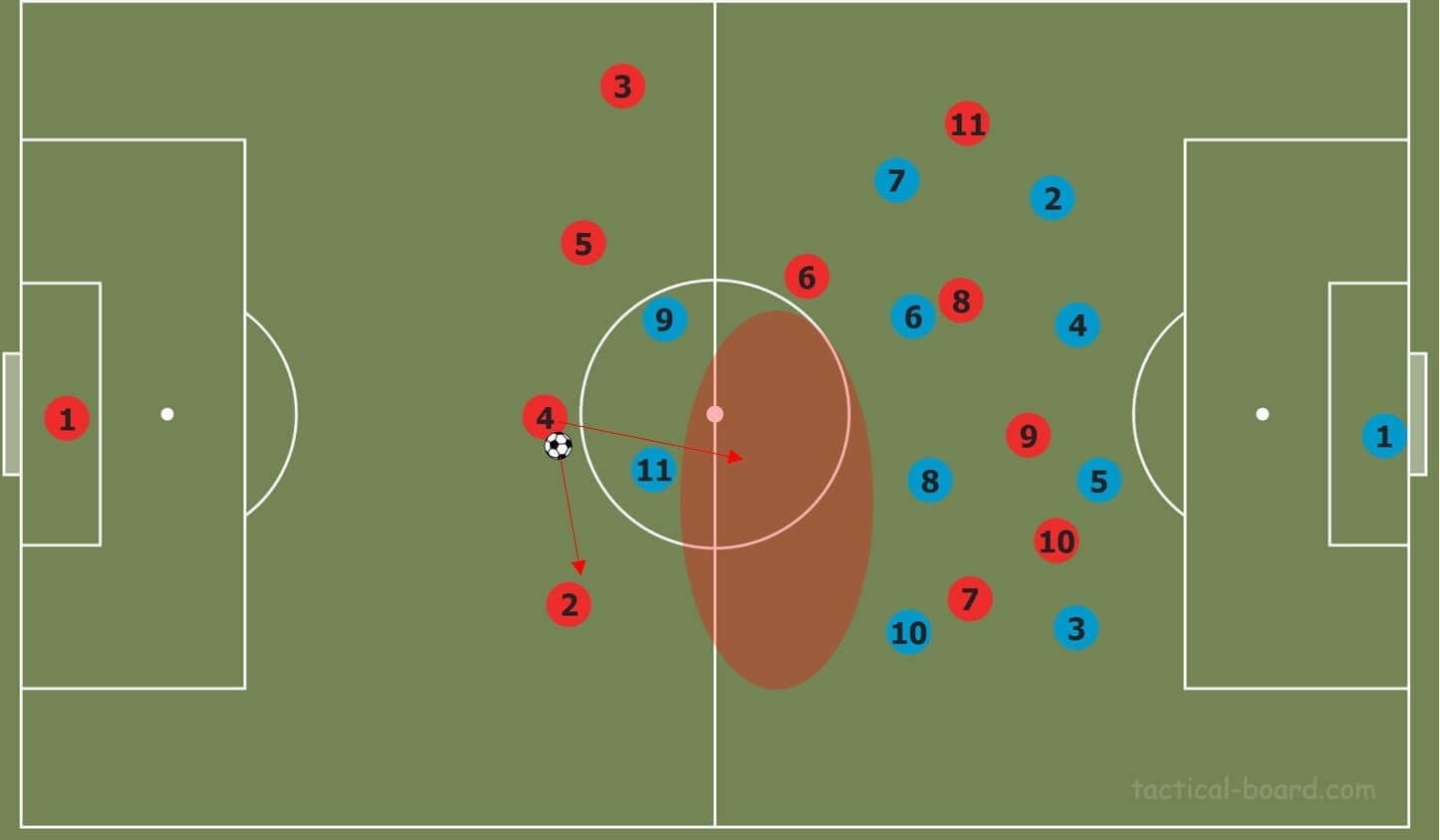

We will begin this analysis with one of Walter’s most innovative strategies in the build-up, which focuses on breaking the first two lines of pressure through the use of the movement of central defenders.

Walter’s playing philosophy in this regard revolves around this idea. When midfielders play the ball laterally or forwards, they are expected to move forward to be in a position to receive another pass, but central defenders are expected to play the ball laterally and remain in position, usually dropping deeper or wider. Why can’t the forward movement of central defenders be used to break lines and progress up the pitch?

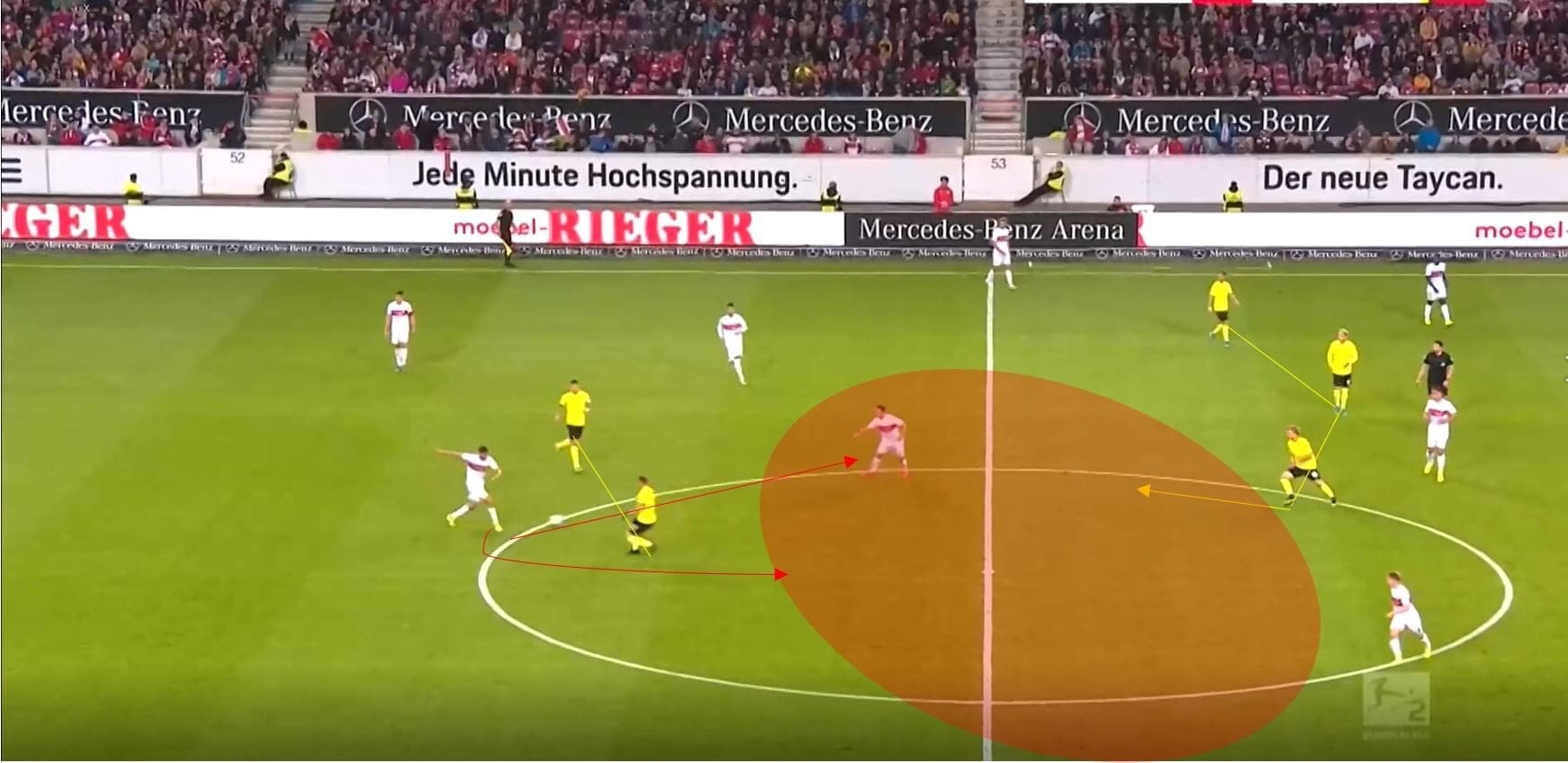

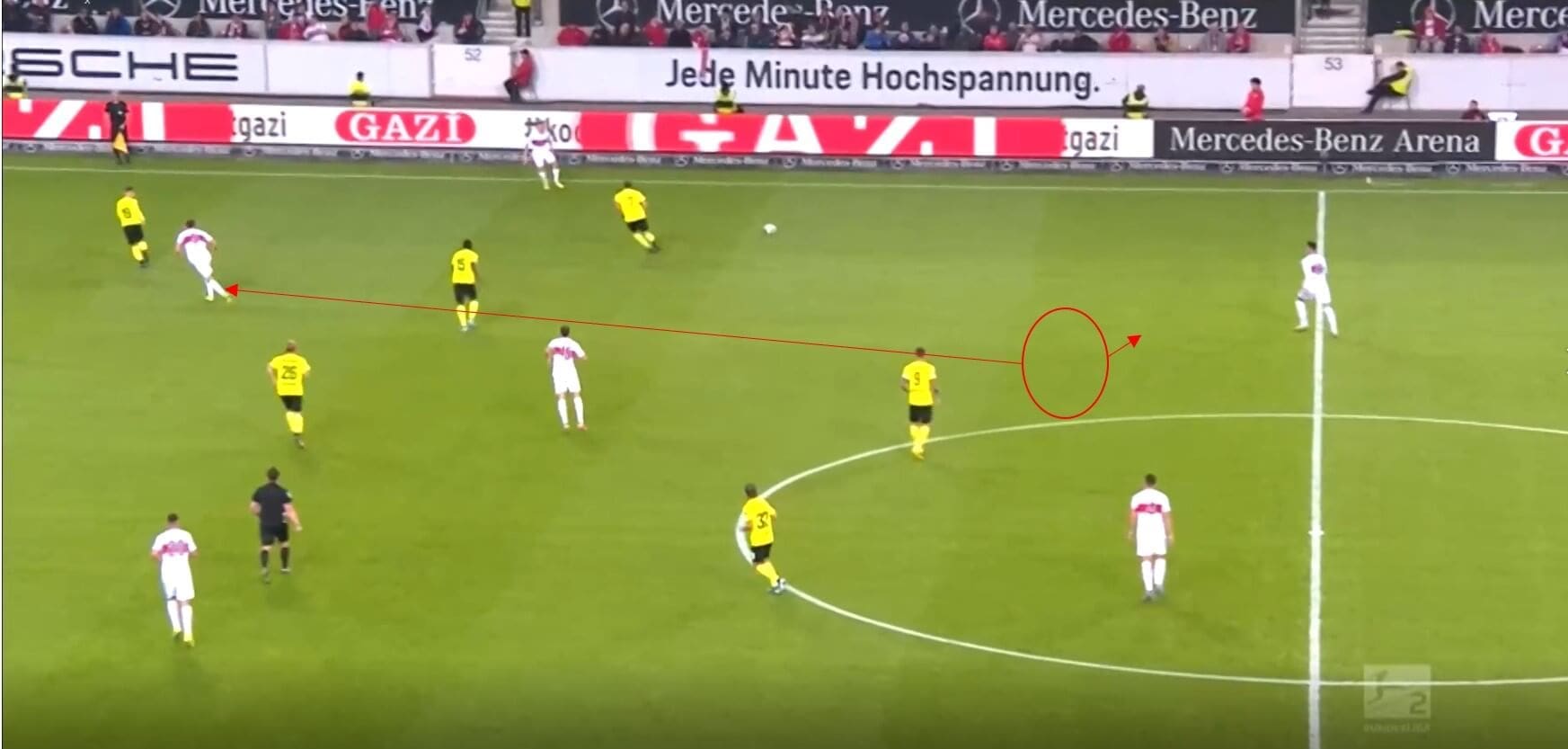

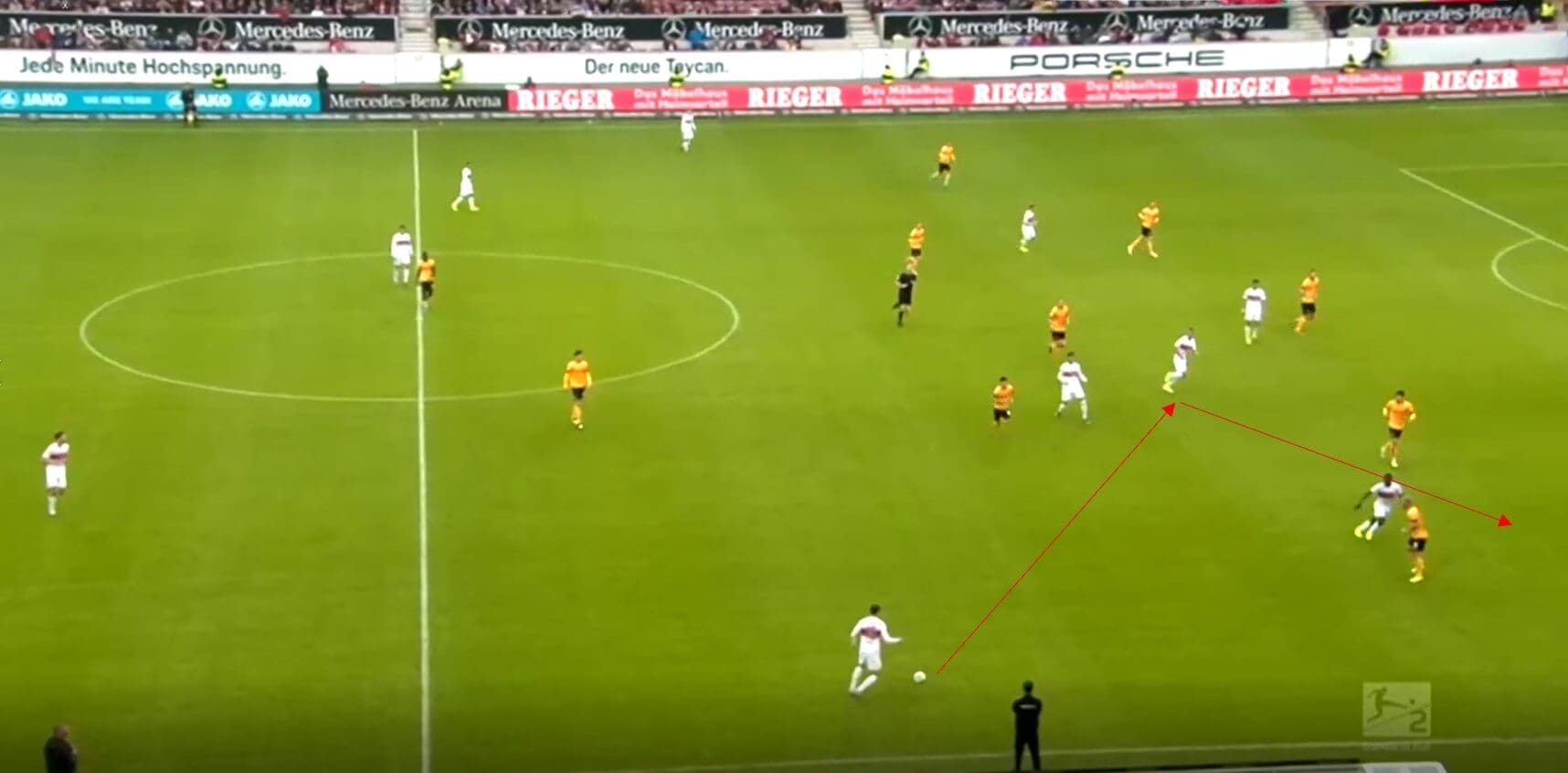

We can see some examples of this below, where in one variation the centre back plays the ball into another advanced central defender. The centre back plays the pass and continues his forward movement past the first line of pressure and into the second. The player receiving the pass is facing his own goal, which triggers a press from the opposition, meaning that when a 1-2 is played the second line of pressure can be bypassed easily.

We can see another example here, where the most central defender plays the ball laterally and then moves forward to receive the ball behind the first line of pressure, again attracting pressure from the second line.

Why do this and what are the advantages?

There are three advantages to using this style of build-up as opposed to say a more conventional style, which I will explain below. These advantages are:

- Better body orientation

- Commits less players in deeper areas

- Harder for the opposition to be press

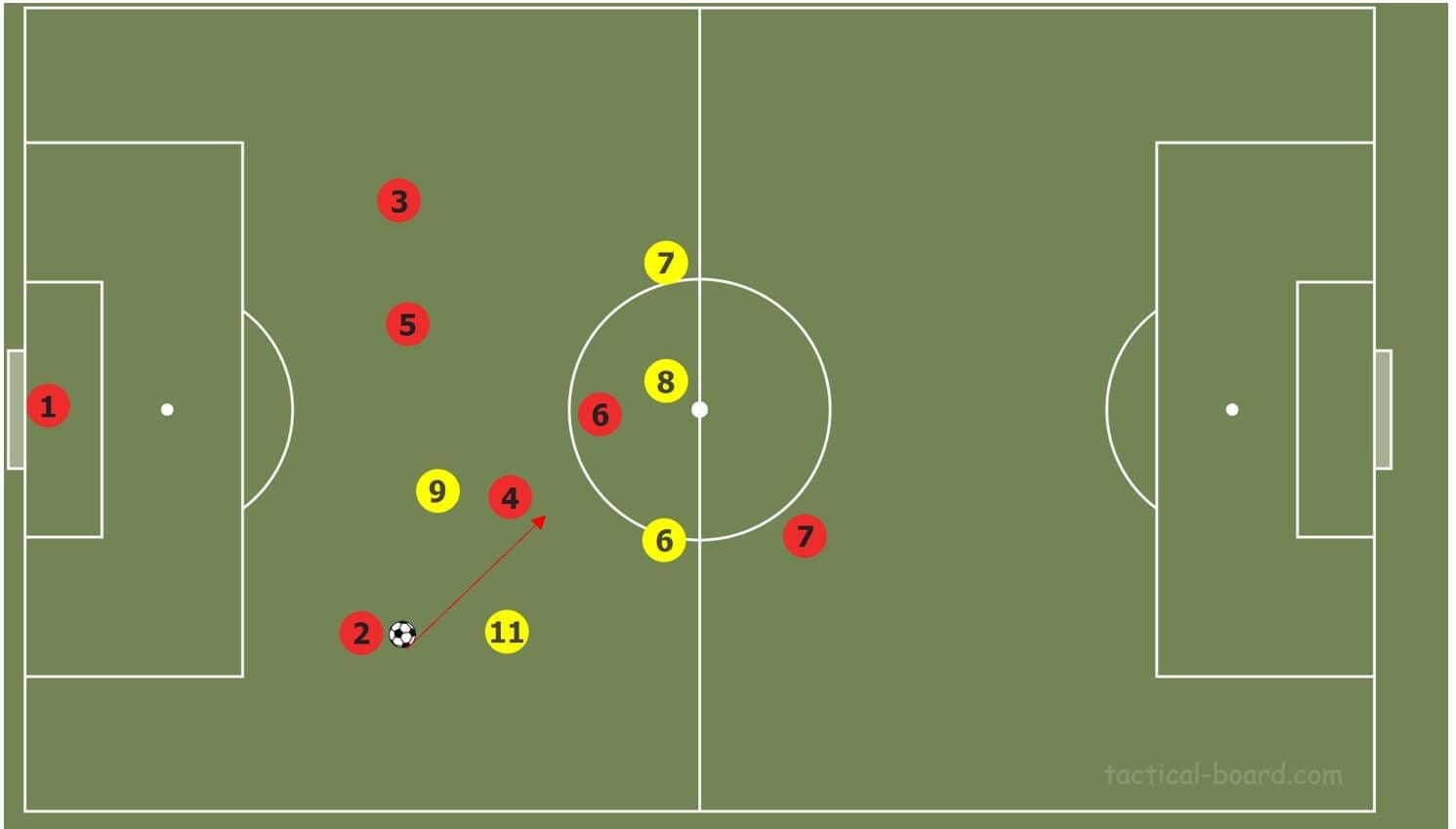

Below again we can see a snapshot of the build-up pattern used by Stuttgart and Walter, with the number four playing wide to the full-back and then making a forward movement past the first line.

Here, we can see a more conventional build-up in a 4-3-3, with the ball near central midfielder and central player dropping.

When we compare the two, we can see the advantages Walter’s methods can have- the first being body orientation. In the conventional shape, the midfielders are receiving facing their own goal, which attracts a press from their midfield markers. Receiving facing your own goal is difficult in deeper areas due to this press, and with the midfielder being unable to turn, passes are often forced backwards, and play is almost reset. Using Walter’s approach, the central defender receives the ball facing forward, and therefore it is much easier to play forward and quicker to progress the ball.

Receiving facing the opposition also makes it harder for the opposition to press as opposed to receiving facing your own goal. Passing options backwards aren’t a problem when pressing from behind, and so the role of any pressing player is to stop the player turning and going forward. When players are running at the pressing player like in the first example above, any lateral or forward pass can be dangerous therefore the pressing player has to get try to cut passing angles quickly. This often leads to the closing of various passing lanes, and the further opening of other lanes forwards, which is where another advantage comes into play.

Walter’s pattern involves the central defender moving from one line to the next whereas conventional build-up involves players staying in one shape in the same lines. Because of this, conventional build-up uses more players in deeper areas, and there is no fluidity and as a result one player can’t perform two roles within the system like they can in Walter’s. Quite simply, as we can see in the two images above, the number seven in conventional build-up must drop to receive, whereas in Walter’s build-up they can stay and occupy the third line (defence), which contributes to a large part of Walter’s strategy and the structure of the side.

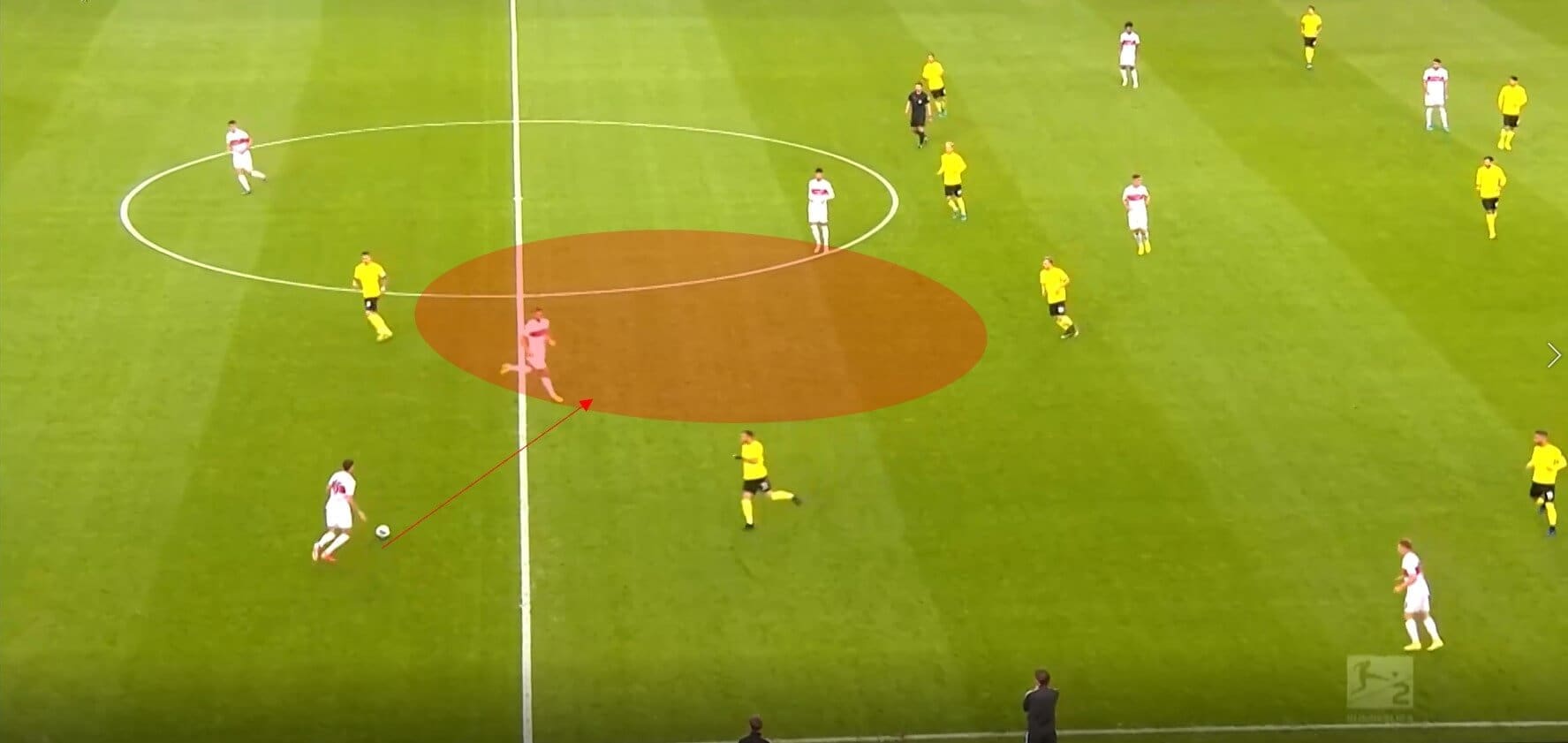

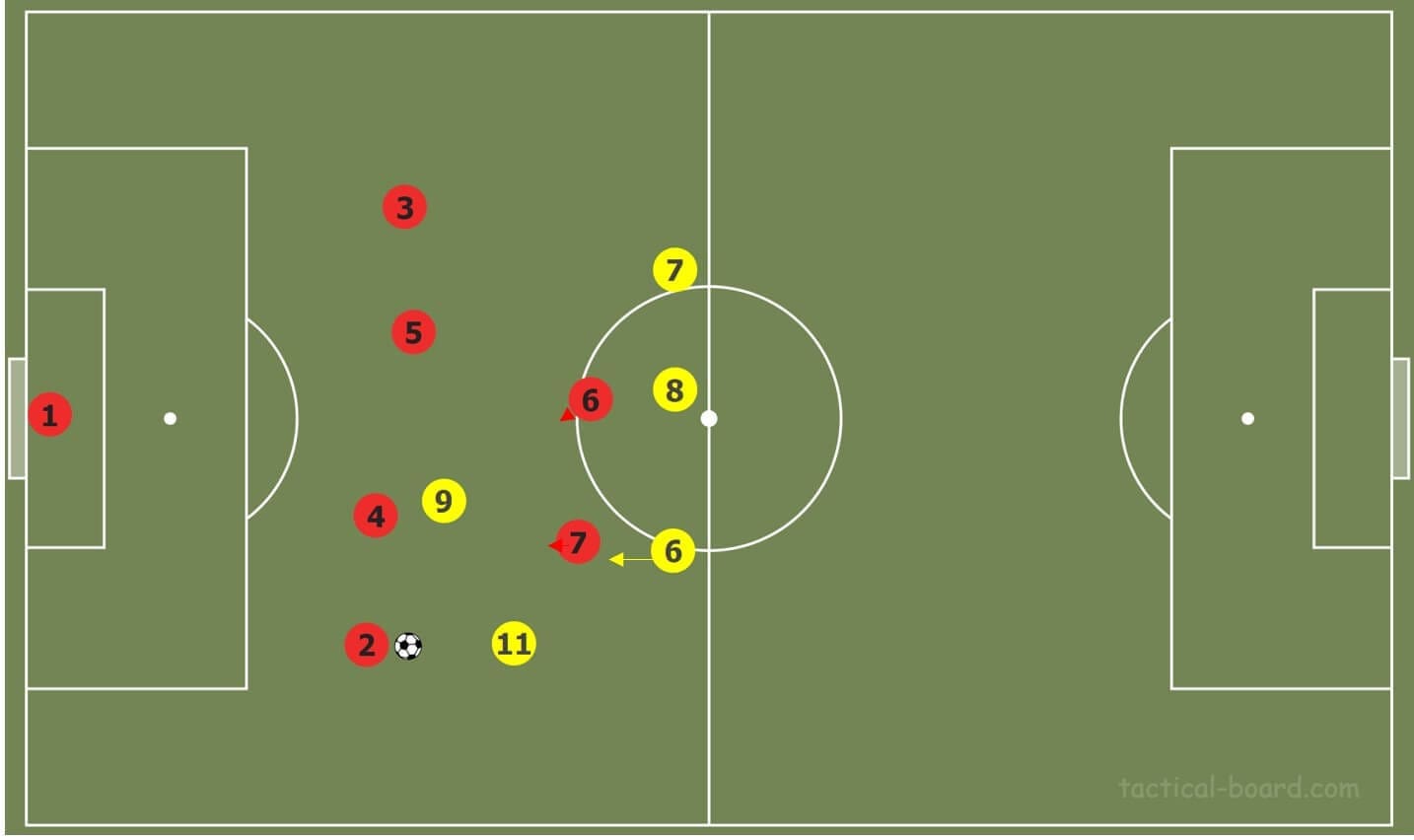

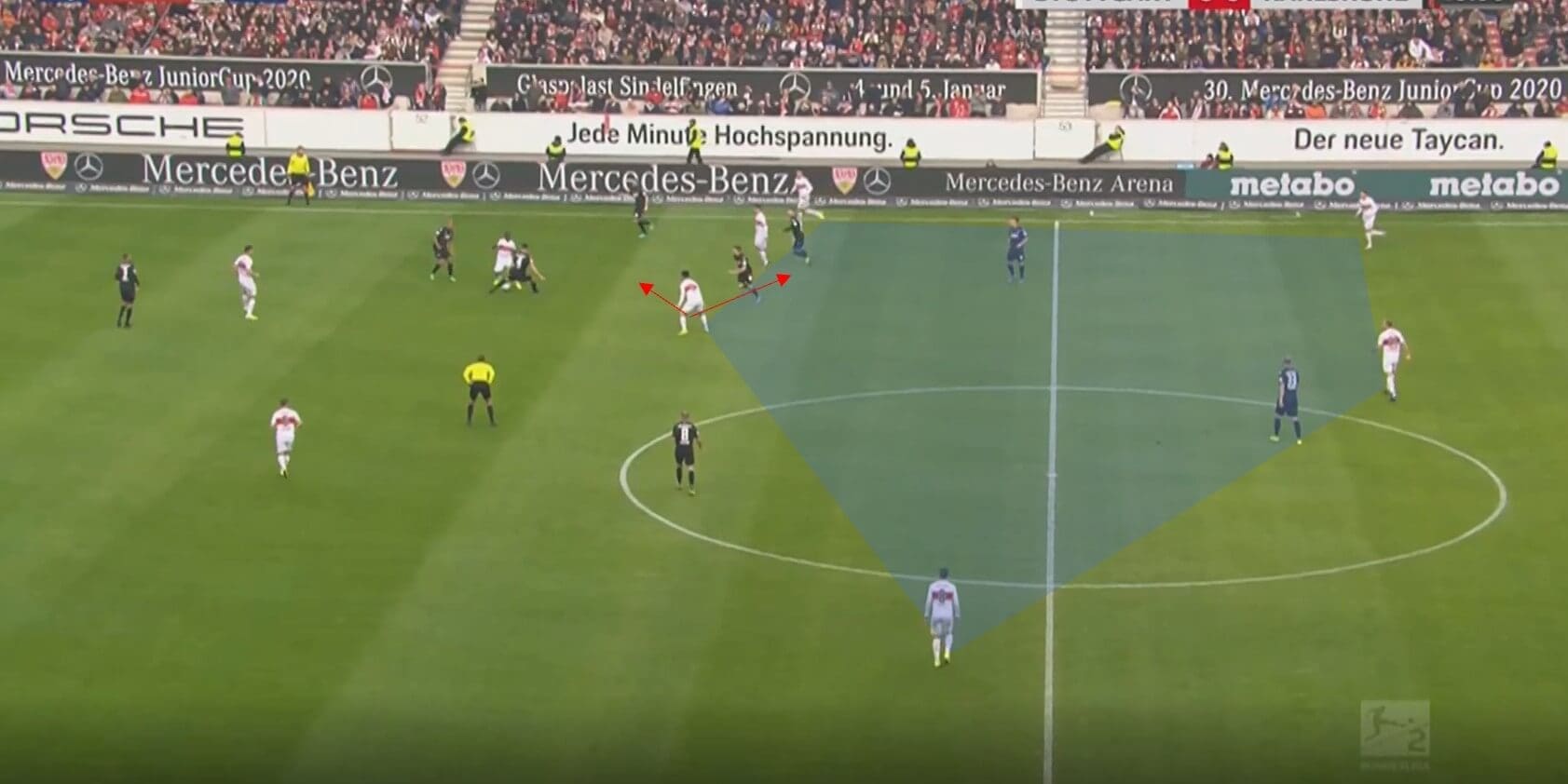

Emptying the pivot

Another innovative strategy Walter uses; which also helps the first pattern discussed, is the emptying of the pivot space. We can see an example of a structure Stuttgart use below, with five players positioned between the opposition’s midfield and defence. Again, in conventional build-up, the number six or pivot would position themselves in line with the ball often, in order to receive. However, Walter’s teams often empty this pivot space as we can see below, with the conventional number six staying more to the left in line with the opposition central midfielder. The structure of the side also helps to pin back the opposition midfield (second line), as they are forced to stay slightly deeper in order to reduce the space between themselves and the defence. Emptying this space therefore creates space to play into, and one of Walter’s key principles can come about- arriving into space to receive, which we have already touched upon in the previous section.

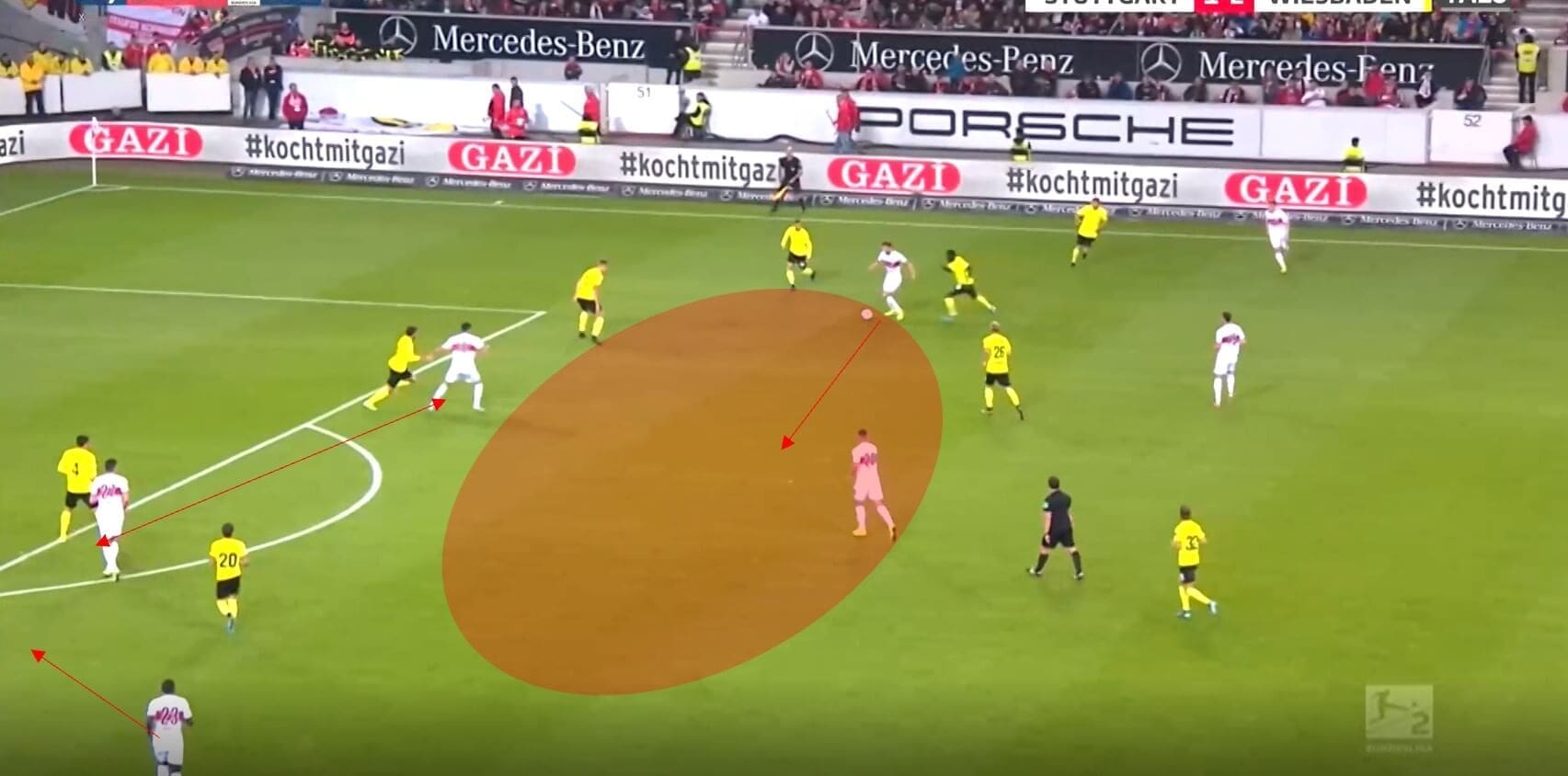

We can see an example here of Stuttgart using their centre backs to occupy the pivot space by arriving in the space to receive. Had a pivot dropped in, they would be immediately followed and Stuttgart would cut off their own space to build up in by attracting more men to that area of the pitch. Here Stuttgart take a risk with the reverse pass, but the centre back can receive at a good angle and can then exploit the higher areas of the pitch.

Overloads on the back line and positional play

As a result of this deep build-up play and the lack of numbers they commit in deeper areas, Stuttgart can therefore commit more players in higher areas, and can create dangerous overloads.

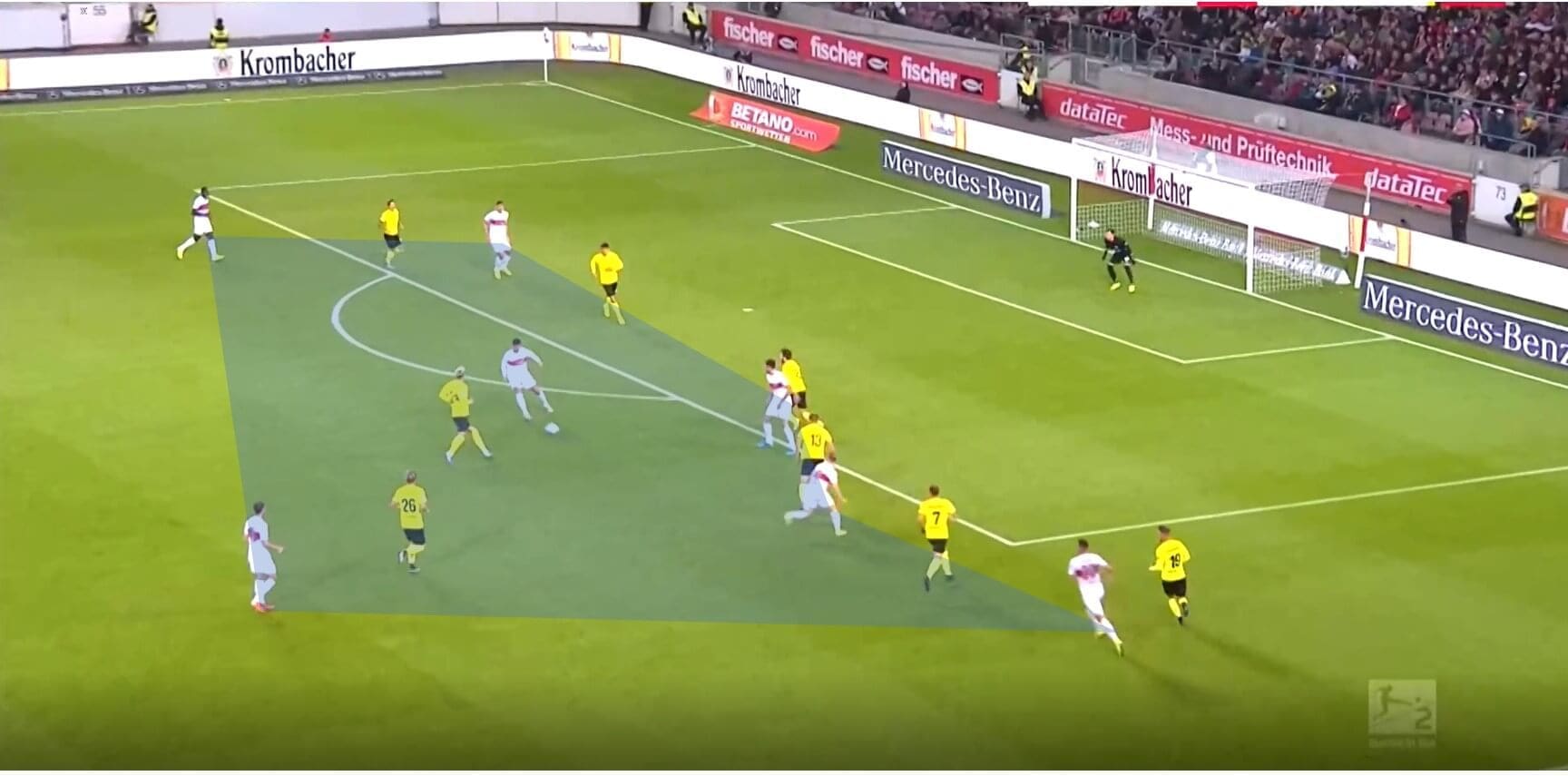

Below we can see a perfect example of Stuttgart’s in possession work, with a centre back driving past the first line and four players occupying the backline, with the potential for a fifth if the ball is switched. This 4v4 on the backline causes issues in spacing, as each player looks to close any spaces for through balls. The main overload is the 2v1 on the left full-back, who is caught between going wide or protecting the inside lane. The striker occupies the two centre backs which prevent the nearest centre back covering across too much, and the pass is eventually played between the full-back and the centre back for a 91st-minute winner for Stuttgart.

Again, below we can see an example of the overloads along the backline, with this time a 5v4 being created. Again, the movement of these players allows space to be created elsewhere, with the widest player making a diversion run out wide to open the passing lane further inside.

This next phase of play also sums up Stuttgart’s play well. Here, on-loan Liverpool central defender Nat Phillips receives the ball in the circle and plays the ball to his fellow centre back before making a forward run behind the second line.

Phillips slows his run, but continues moving, arriving into the half-space as he receives the ball on a diagonal from a central midfielder who has dropped wide. From there, Phillips body orientation allows him to continue to go forward, and we can see Stuttgart have an overload on the defending side Wiesbaden, with Stuttgart’s left-back also out of shot. Phillips should play to the edge of the box where Stuttgart can create a goalscoring opportunity, but instead plays to the ball near player and Wiesbaden have an opportunity to recover. Should Stuttgart be promoted I am sure Walter will be looking to boost his personnel, with Phillips struggling during his time in Germany so far both in and out of possession.

We can see another example of this here, with the centre back playing the ball and moving behind the second line. We can see again Stuttgart don’t occupy this space, with the ball carrier actually telling the striker to stay and not drop deep, and then plays the ball wide. Phillips can then receive while facing forward.

This final example in this section shows the use of this half-space is common, and again we can see the principle of arriving into space and receiving, rather than waiting in space to receive. We know that’s what happened because of his body orientation, again. There is then a 4v6 overload in Stuttgart’s favour in the middle.

All of these examples also indirectly show the extreme rotations Walter’s side make throughout the game, but this is much easier to capture using video analysis. Players in defence rotate in the backline as shown and move forward, where they are covered by a central midfielder at times. Players who occupy the opposition backline also consistently rotate as shown, in order to create space for each other by vacating and entering space.

Third man runs

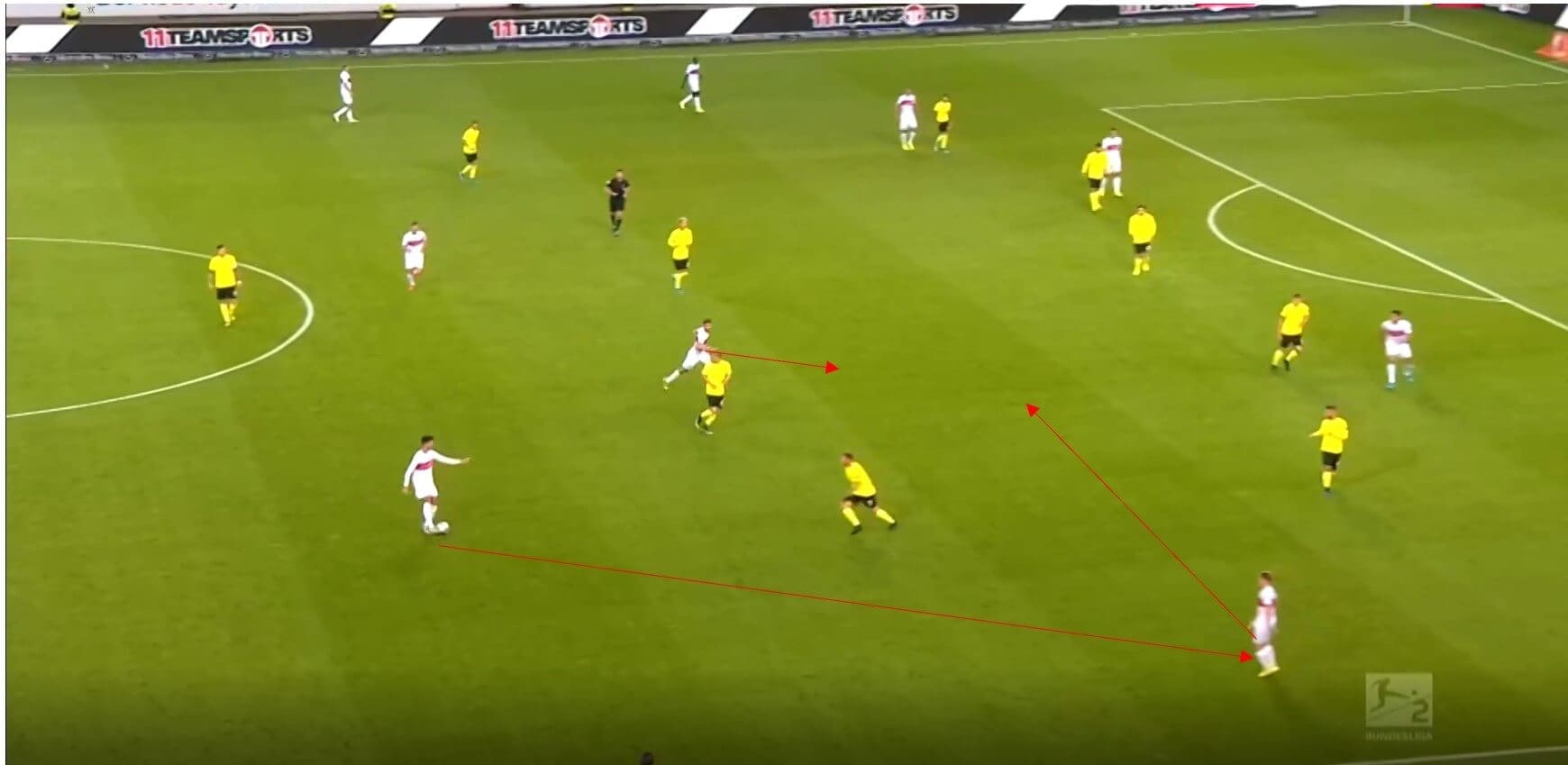

For all the fluidity of the side they do still maintain a structure around a pass which allows them to play third man passes to progress. Stuttgart’s rotations still offer depth, width and height in their shape in order to progress, as we can see in the examples below.

Here, the ball is played inside on a diagonal, and the wide player immediately starts his run in behind. The width of this player also allows for more space to be created in the middle for the player receiving, and the player positioned behind him could even continue his run to commit more players to the attack. A simple but extremely effective way of getting in behind.

Here we can see another third man pass, which is extremely well worked. Here, two players commit to the wide areas, and also commit their two markers, which opens up space to play inside to the striker, providing height in the play. There is then a rotation between the two wide players, with the player furthest from the striker sprinting into the central space created and receiving the ball from the striker Mario Gómez.

Counter-pressing

All of this extremely expansive build-up can cause problems to the counter-pressing structure of the side, and as a result Stuttgart do concede lots of counter-attacking goals. While the lack of a pivot player does help Stuttgart to progress up the pitch, it does upset their counter-press, as we can see in the example below.

Here Stuttgart are about to lose the ball, with a duel taking place further up the pitch. The most defensive-minded midfielder Wataru Endo has the option of pressing the ball in order to cut angles and possibly regain possession or cut the passing lane through into the space seen. Endo does neither of these and instead stays in this position. A loose ball or a 50:50 duel should be a trigger for the counter-press, with all the ball near players looking to sprint towards the ball (in a ball orientated counter-press) in order to cut angles and stop a counter-attack.

Therefore, with one simple pass, the counter-press (or lack of) is broken and the opposition have a 3v2, but the height of Stuttgart’s line, and the timing of the run, saves them.

In this example, the Stuttgart player receives the ball poorly and is unable to go forward and receive the ball cleanly, so loses possession. Stuttgart have seven players committed forward, and the depth they have in possession is no longer in line with the ball.

As a result, when the ball is lost, Stuttgart are in a poor position to counter-press with no bodies close to the ball or behind it, which allows the opposition to counter-attack.

The dilemma which comes from this issue is of how to fix it. Do Stuttgart cut back their build-up play slightly and commit more players back in order to be more solid, or do they get better at retaining possession and stop losing the ball. The amount to which you can get better at not losing the ball is difficult, considering sides like Manchester City still have counter-pressing issues, and big ones recently. One idea could be to still vacate the pivot position in deep build-up, but then after the team reaches a certain height have a player or players drop back into a holding midfield role, however this of course damages the attacking play. Therefore, if Stuttgart are promoted, I would expect some kind of adjustment from Walter, but what those adjustments could be is probably a whole other 2000 word plus analysis.

Conclusion

Tim Walter’s style of play is innovative and risky, but is showing signs of success this season at Stuttgart. The better his players become, the better his system will work, and therefore it is vital that Walter is able to get Stuttgart promoted this season, so in the new year he can recruit better quality players to play within the system. Walter’s principles around build-up and space creation and utilisation are excellent, innovative ideas, and hopefully this article has addressed these principles and made them easy to understand.

Comments